Ichnofabric analysis of bathyal chalks: the Miocene Inglis Formation of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India

Bhawanisingh G. Desai

School of Petroleum Technology, Pandit Deendayal Energy University, Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India

Abstract In the Bay of Bengal,the Andaman and Nicobar Islands represent part of the Burma-Sunda-Java subduction complex. The Islands are composed of sediments ranging in age from Jurassic to Recent, represented by ophiolites, flysch sediments, along with deep marine sediments scraped off from the subducting plate. The stratigraphic succession that overlies meta-sedimentary and ophiolite suites consists of turbidite and non-turbidite sequences, along with thick-bedded nannofossil chalks. The present study describes ichnofabrics of chalks from the Inglis Formation(Early to Middle Miocene).These chalks are highly to moderately bioturbated and comprise several levels of ferruginised layers as weak discontinuity surfaces. The studied section shows the recurring occurrence of ichnotaxa belonging to Asterosoma, Chondrites, Cladichnus,Ophiomorpha, Palaeophycus, Planolites, Taenidium, Thalassinoides, and Zoophycus. Sediments are represented by Bioturbation indices varying between BI-2 to BI-5, represented by (a) light coloured trace fossils in dark sediment (LID ichnofabric) and (b) dark coloured trace fossils in light sediment (DIL ichnofabric). Ichnofabric analysis suggests multiple colonization, complex tiering, and multilayer tiering. The LID ichnofabric exposed at Kalapathar reveals three tiers,a diverse shallow tier and a moderately low diverse middle and deep tiers. At the Lacam Point Section,in contrast, the LID ichnofabric is represented by condensation of the tiers and the absence of shallow tiers. The DIL ichnofabric at the Kalapathar Section seems to be more expanded and is represented by four tiers with extensive bioturbation. Ichnofabric analysis supports deposition of the chalk sediments in a lower bathyal paleoenvironment and suggests that organic matter, pore water, and bottom-water oxygenation were the main controlling factors. Thus, the ichnofabric analysis of the Early-Middle Miocene Inglis Formation gives first-hand information regarding the poorly known chalk facies of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands pre-Bengal fan stage of the Indian plate.

Keywords Ichnofabric, Nannofossil ooze, Chalk, Bathyal, Bay of Bengal, Miocene

1.Introduction

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands are part of the Burma-Sunda-Java subduction complex. Its tectonostratigraphic elements are strikingly parallel to the Java Trench trend.The oceanic part of the Indian Plate is subducting towards the east below the oceanic part of the Southeast Asian Plate. Subduction during Late Oligocene gave rise to a fore-arc basin in between Main ridge (Andaman and Nicobar Islands) and volcanic chains (Barren Island). The Neogene sediments accumulating in the fore-arc basin contain a significant amount of biogenic sediments deposited mainly at great depths (Sharma and Srinavasan, 2007). The north-south trending Neogene strata belong to the Archipelago “Group”.

The marine biogenic calcareous sediments,composed of calcareous nannofossils and/or foraminifera, are classified as chalks, with its non-lithified variant known as ooze (Fabricius, 2007; Pickering and Hiscott, 2015). These chalks have been deposited above the Calcite Compensation Depth with its deposition controlled by sediment supply (“planktonic rains”),dissolution and rate of erosion(Scholle et al.,1983). The chalks are characterized by uniform lithology, continuous bioturbation, and absence of any physical sedimentary structures.During the Mesozoic,chalks with similar lithological characters were also deposited in the epicontinental seas in Europe(Ekdale and Bromley, 1984a, b). However, these chalks varied in their ichnological content, with shallower chalks dominated by Thalassinoides and deeper chalks having rare or no Thalassinoides(Savrda,2012).Several deepsea drilling cores(DSDP,ODP,and IODP)have revealed that deep marine chalks are having complex ichnofabric and tiering histories reflecting multifaceted deposition of the sediments(Werner and Wetzel,1982;Wetzel, 1983; Ekdale and Bromley, 1984a, b; Buatois and M′angano, 2011; Savrda, 2012).

Andaman and Nicobar Islands form a critical stratigraphic entity for interpreting the palaeoceanography and palaeoenvironments of the subducting Indian Plate. Despite this, trace fossils have scarcely been studied or described from sediments of the Islands.Previously,Badve et al.(1984)made a passing remark on the occurrence of Ichnogenus Torrowangea from the rocks near the mud volcanoes at Baratang. The first systematic description of the trace fossils was made by Bandhopadhaya et al.(2009) who reported Thalassinoides paradoxicus, Thalassinoides suevicus, Lorenzinia apenninica and Teichichnus stellatus from the Eocene submarine fan deposits of the Namunagarh grit of South Andaman Island.Anuj et al.(2016)published a detailed account of trace fossils from Paleocene deposits of Northern Andaman Island. They described Arenicolites, Chondrites, Gyrolithes, Rhizocorallium,Taenidium, Planolites, Skolithos, and Thalassinoides from the Mithakari Group. Most of the ichnological work from the Islands is restricted to turbidite or similar environments, whereas, ichnological work on the chalk or ooze environments is nearly absent. The objective of the paper is to understand the ichnofabric variations of upwelling influenced deep-water chalks during Miocene. The paper describes the trace fossils and ichnofabric analysis of the Early to Middle Miocene,thick-bedded chalk sequence known as Inglis Formation, deposited in a forearc basin of the Andaman subduction zone.

2.Geology and stratigraphy

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands are situated in the Bay of Bengal (Fig. 1). West of the Andaman Islands, the oceanic Indian Plate is subducting below the oceanic Southeast Asian Plate (Seely et al., 1974)also known as the“Burma microplate”(Curray,2005).To the east of these Islands, young volcanoes of the Barren and Narcondam Islands are part of the inner arc.Tectonically,the Andaman and Nicobar Islands are categorized from west to east into (a) Andaman Trench/Inner Slope(b)Outer High/Trench slope break(c) Fore Arc Basin (d) Volcanic Arc (e) Back Arc Basin,and (f) Mergui Terrace (https://www.ndrdgh.gov.in,2015).

Rocks of Andaman and Nicobar Islands comprise ophiolites, flysch sediments, and deep marine sediments,forming an accretionary prism on the outer arc ridge of the subduction zone (Sharma and Srinavasan,2007; Allen et al., 2008; Bandopadhyay and Carter,2017a, b).

Stratigraphically,the Andaman and Nicobar Islands expose strata ranging in age from Jurassic to Recent(Fig.1c).The stratigraphic sequence starts with metasedimentaries and ophiolite suites of the Late Cretaceous to Eocene Porlob and Serpentine groups, followed by Baratang Group.Badve et al.(1984)obtained Cretaceous to Paleocene foraminifers along with trace fossils. The Baratang Group is overlain by turbidite sequences of the Port Blair Group of Late Eocene to Oligocene age(Bandopadhyay and Carter,2017a).The Early Miocene to Pleistocene Archipelago Group unconformably overlies the Port Blair Group. The microfossil rich sediments of the Archipelago Group have been deposited in deep marine environments(Srinivasan and Azmi,1976c).The Archipelago group is subdivided into seven formations, respectively as Strait(Lower Miocene),Round(Lower Miocene),Inglis(upper Lower to lower Middle Miocene), Long (early Middle to Upper Miocene), Sawai Bay (Upper Miocene to upper Lower Pliocene), Guitar (Upper Miocene to Upper Pliocene), and the Neil (Upper Pliocene to Pleistocene) formations (Fig. 1c). Bandopadhyay and Carter (2017a) recently reviewed, and provided a new discussion on the geological evolution of the Archipelago Group.

Fig.1 Location and geology of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.a-Location Map of the Andaman-Nicobar Islands showing the division of the Andaman Island and Ritchie's Archipelago;b-Inferred geological map of Havelock Island showing the location of the studied section along with other sections of importance(information is compiled from Sharma and Srinivasan,2007); c-Litho-and biostratigraphic classification of the rocks on Ritchie's Archipelago sediments with the assumed palaeo-bathymetry (redrawn after Sharma and Srinavasan, 2007).

In the Archipelago Group, the Inglis Formation is characterized by a thick succession of nannofossil chalk. The formation was proposed by Srinivasan and Azmi (1976b) who designated the entire Inglis Island as type area and the west-coast cliff section of Inglis Island as its type section. Additionally, the succession was mapped along the John Lawrence Island,Havelock Island (Lacam Point, Meetha Nala, Kalapathar and West Coast Section),Henry Lawrence Island;Nicholson Wilson Island and the Long Island(Srinivasan and Azmi 1976b; Sharma and Srinavasan, 2007). Stratigraphically,the formation is conformably overlying the Strait Formation and is overlain by the Long Formation,except at the Meetha Nala Section of Havelock Island,where a hiatus is present (Pandey et al., 1992). Previously, the Inglis Formation has also been known as Muralat chalk (Karunakaran et al., 1968).

Sedimentologically, the sediments of the studied sections fall under facies class G1.1 of Pickering et al.(1986). The facies class G is characterized by dominance of biogenic oozes and hemipelagic sediments with less than 5% terrigenous sands (Pickering et al.,1986). In present case, the studied sediments are predominantly composed of tests of planktonic foraminifers, nanoplankton, diatoms, and radiolarians(Fig. 2b and c), with a minor amount of clay and volcanic glass shreds. The sediment grain-size ranges from 0.5 μm to 64 μm. These chalks are highly to moderately bioturbated and comprise several weak discontinuity surfaces characterized by ferruginous layers. Previously published literature on this formation is based on microfossils (including foraminifera and nannoplankton) and estimated water depths of between 2000 and 3000 m for deposition of the chalk(Sharma and Srinavasan, 2007, p. 127). Two sections have been selected for study on the Havelock Island(a)Kalapathar Section and (b) Lacam Point Section(Fig. 1a and b). At the Kalapathar Section, the base forms the upper part of the Jarawaian Marine Andaman stage corresponding to the interval marked by the first appearance of Globigerinatella insueta (= N7 of DSDP site 289,Srinivasan and Kennett,1981).The sediment is represented by soft creamish white nannofossil chalk associated with siliceous chalk and abundant glass shards(Fig.2).Based on the whole rock,SEM images of Kalapathar samples show a better preserved but smaller coccolith size than the usual size of the taxa.The common occurrence of nannoplankton includes species of Discoaster along with abundant Coccolithaceae(Fig.2b and c).The strata of the Lacam Point Section belong to the Inglisian stage,ranging from the base of the Praeorbulina glomerosa Zone to the Globorotalia fohsi Zone (Sharma and Srinavasan, 2007).Palaeobathymetric interpretation is inferred based on planktonic and benthic foraminifers (including deepwater calcareous benthic forams, such as Sphaeoroidina,Pleurostmella,and Globocassulina;deepwater agglutinated foraminifers; porcelaneous foraminifers); nanoplankton and radiolarians. The data indicate that the chalks were deposited in a bathyal environment, especially in the lower bathyal zone(Srinivasan and Azmi, 1976a, b, c; Sharma and Srinavasan, 2007). Trace fossils and ichnofabric studied here are from the thick-bedded chalk belonging to the Early to Middle Miocene Inglis Formation.

Fig. 2 a- Kalapathar and Lacam Point sections, sample position for SEM studies is indicated by star symbol; b- SEM image of a sample from lower levels at Kalapathar with abundant nannoplankton, radiolarians and foraminifers. Red arrow: six-armed Discoaster; yellow arrow:coccolithales;R:radiolarians;c-SEM image of another sample showing abundant small coccolithales.The SEM image was taken at 5.0 kV EHT and 10.7 mm WD.

Kalapathar Section(Lat 11058′56′′N;Long 93000′56′′E): The section starts with massive to mediumbedded nannofossil chalk with abundant glass shards and tephras at the base. A thick unit of interbedded calcareous silty sand and feebly calcareous shales(Figs. 2 and 3a)caps the section. Lacam Point Section(Lat 12002′55′′N; Long 92057′54′′E): The section consists of thick, massive, creamish yellow chalk and silty mudstone. Several thin ferruginous layers interrupt the massive chalk (Figs. 2; 3b, c, d). In both studied sections the trace fossils Asterosoma isp.;Cladichnus isp.; Chondrites intricatus; Chondrites targionii Ophiomorpha cf. rudis; Palaeophycus tubularis; Palaeophycus heberti; Planolites beverleyensis;Taenidium serpentinum; T. suevicus, Zoophycus brianteus, and Zoophycus villae are common (Figs. 4 and 5).

Fig.3 Details of the studied sections a-Kalapathar Section exposing the lower part of Inglis Formation in the intertidal zone.The beds dip 400 in an easterly direction and are well exposed during low tides (Scale at right lower corner-1.5 m); b- Middle to upper part of the Inglis Formation at Lacam Point Section showing steeply dipping succession.The blue arrow indicates position of the Lacam Point lighthouse(Scale at right lower corner-1.5 m); c- View of the Inglis Formation at Lacam Point Section (Scale at right lower corner-1.5 m); d- Characteristic bioturbated Inglis Formation at Lacam Point showing alternating dark and light coloured bands. Scale at right lower corner-1.0 cm.

3.Methods of study

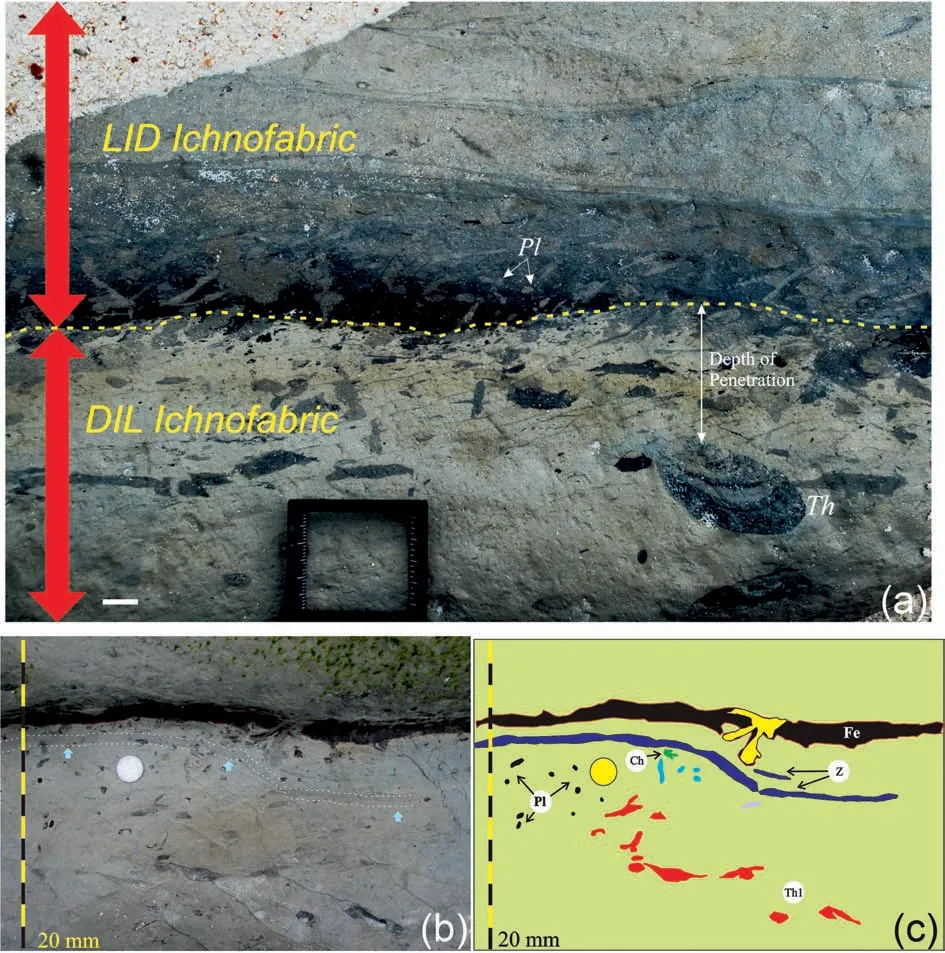

Two sections, Kalapathar and Lacam Point, were investigated for their trace fossil content. The ichnofabric attributes were studied and noted in the field.Ichnofabric analysis followed the methodology suggested by Savrda and Bottjer (1989) and Taylor et al. (2003). Whenever possible, the trace fossils were photographed in cross-sectional view. The photographs were later ondigitally enhanced to delineate piped zone ichnofabric and transitional zone ichnofabric. Dark in light (DIL) and light in dark (LID) ichnofabrics were studied separately(Fig.6a).Trace fossils from each zone were computed and analysed statistically to understand the changes occurring in the sections.

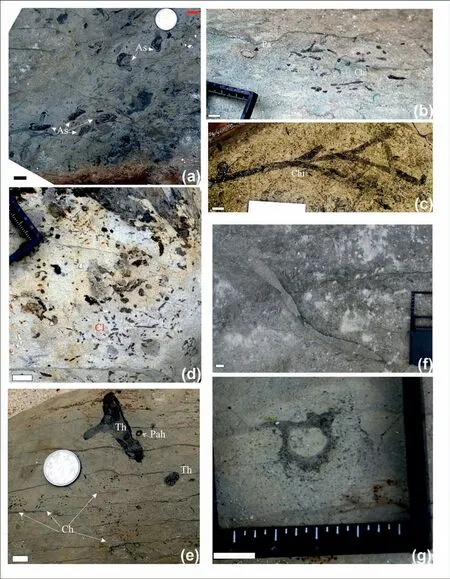

Fig.4 Ichnology and ichnofabric of the Inglis Formation.Scale at the left lower corner 1 cm.a-Inclined cross-sectional view of Asterosoma(As)occurring as a passively filled cluster of elliptical bulbs;Kalapathar Section;b-Chondrites intricatus(Chi)occurring as a cluster of smalldiameter burrows at acute angles showing different fill,Paleophycus tubularis(Pa)occurring as thin-lined burrow in cross-section(arrowed),Kalapathar Section; c-Large Chondrites targionii with acute branching, Kalapathar Section; d- Small-diameter radiating Cladichnus isp. (Cl)indicating downward branching,Kalapathar Section;e−Cross-cutting relation of Chondrites intricatus(Ch),Palaeophycus heberti(Pah),and Thalassinoides (Th), Kalapathar Section; f- Ophiomorpha cf. rudis in the lower part of the Inglis Formation showing thin-walled burrow; g-Cross-section showing a moderately thick wall of Ophiomorpha.

Fig. 5 Ichnology and ichnofabric of the Inglis Formation. Scale at the left lower corner 1 cm. a, b- Cross-sectional view of Planolites beverleyensis occurring as circular to elliptical sections with a fill differing from the host rock; c- Taenidium serpentinum showing distinct arcuate-shaped backfill menisci of alternate colour,Lacam Point Section;d-Zoophycus briantius(Z)cross-cut by Chondrites(Ch)in the upper part of the Lacam Point Section; e−Zoophycus villae in cross-section showing discontinuous laminae and absence of a marginal tube,Kalapathar Section; f- Zoophycos insignis showing antler-like spreiten, Kalapathar Section.

In some cases, trace fossils reflecting similar morphology were grouped for ichnofabric analysis.Especially Ophiomorpha and Taenidium are rare in the sections,and for ichnofabric parameters such as depth of penetration and cross-cutting relations, Ophiomorpha cf rudis is calculated along with Thalassinoides data and Taenidium serpentinium is calculated with Zoophycus data. Additionally, all Zoophycus species are calculated as a single genus for ichnofabric analysis.

4.Results

4.1. Ichnology

Fig.6 Technique of ichnofabric analysis adopted in the present study.a-Idealized section at Kalapathar showing the development of LID and DIL ichnofabric and depth of penetration of various ichnotaxa(Scale at left lower corner-1 cm);b,c-Section of chalk showing a ferruginous layer representing a break in sedimentation and bedding plane. The cartoon shows the depth of penetration of various ichnotaxa (Fe=Ferruginous layer, Ch = Chondrites, Pl=Planolites, Z = Zoophycus).

Asterosoma isp. (Fig. 4a) is a bulbous, radiating,straight to curved burrow made up of clustered bulbshaped, aligned horizontal or oblique segments.Bulbs are elongated with a tapering end and connected with a central axis. In the study area, Asterosoma occurs in cross-sectional view as elliptical to elongate,and bulbous segments are 10-25 mm in diameter.The sectional view usually shows 2-5 bulbs up to 15 mm in diameter occurring as a cluster. Individual bulbs are filled with concentrically or eccentrically arranged,alternating dark and light laminae. It co-occurs with

Chondrites,Palaeophycus,Planolites,and Zoophycus.The laminated nature of the burrow infill is similar to that of Asterosoma ludwigae.

Asterosoma is considered as the trace of a depositfeeding animal.It commonly occurs in shallow marine settings.However,it has also been recorded from deep marine environments (Uchman and Wetzel, 2011;Knaust et al., 2014). It widely occurs from the Early Cambrian (Desai et al., 2010) until the Holocene(Dashtgard et al., 2008; Knaust, 2017).

Chondrites intricatus(Brongniart,1823)(Fig.4b,e)is a dichotomously branched, radiating burrow. The tunnels are elliptical or flattened in cross-section, occasionally showing second-third order branching. The burrow fill is darker-coloured than the host rock. The species is distinguished by its characteristic thin and slender branches. The ichnotaxon is regarded as a feeding or chemosymbiotic burrow(e.g.Fu,1991).Patel and Desai (2009), based on observations in the recent intertidal zone, considered it a combined feeding and dwelling burrow.

Chondrites targionii(Brongniart,1828)(Fig.4c)is similar to Chondrites intricatus in its branching and burrow fill pattern.It differs,however,by its long and dominating second-order branches(Uchman, 1999).

Cladichnus isp. (Fig. 4d) is a radiating, primary successively branched burrow with meniscus-shaped segments. The present burrows are thinly walled,oriented horizontally to inclined, showing successive branching. The branches exhibit weakly defined menisci. Burrow fill is darker than the host sediment.The ichnogenus is regarded as a deposit feeder or as a chemosymbiotic structure (Uchman, 1999).

Ophiomorpha cf. rudis (Fig. 4f and g) Its occurrence is rare, limited to the lower part of Kalapathar succession, and occurs as a three-dimensional burrow network with a typical pellet-lined walled. In the sections,the trace fossil appear as a thin-lined,weakly pelleted burrow of vertical to inclined orientation.Burrow fill is similar to the host sediment. Uchman(2009) considered it a very deep feeding burrow occurring in the channel and proximal depositional lobe facies of deep-sea fans or in the thick-bedded facies of deep-sea clastic ramps.

Palaeophycus tubularis Hall (1847) (Fig. 4b-Pat)

is a thin-lined horizontal to sub-horizontal,cylindrical burrow.It is typically unbranched with distinct a lining and passive fill. In the sections, it can be observed as thinly lined circular to elliptical passively filled burrows. the ichnospecies occurs in a wide range of environments, also in deep marine sediments.

Palaeophycus heberti Saporta (1872) (Fig. 4 E)are sub-horizontal to horizontal burrows, elliptical to circular in cross-section, similar in occurrence to P.tubularis. However, P. heberti is distinguished by its thick lining.

Planolites beverleyensis Billings, 1862 (Fig. 5A and B) is a simple, horizontal to inclined, unbranched burrow with an active fill burrow. In sectional view, it occurs as dense, straight to curved burrows with circular to elliptical cross-sections and a burrow fill differing from that of the host rock. Planolites is cosmopolitan and occurs in all depositional environments. It is also a constituent the of Nereites ichnofacies (Buatois and M′angano,2011).

Taenidium serpentinium Heer (1877) (Fig. 5c) is relatively rare and occurs as a cylindrical to elliptical burrow with distinct backfill menisci.In cross-sectional view, they are sub-horizontal to sub-vertical. The burrow fill shows characteristic alternate-coloured arcuate menisci.

Thalassinoides suevicus (Rieth, 1932) (Fig. 4e) is a three-dimensional burrow. Its cross-section is circular to elliptical, in plan-view Y-shaped branching occurs. At branching points, the burrows are enlarged.Burrow fill is darker than the host rock. The ichnospecies is a common element of the chalk and other carbonate environment (e.g., Ekdale and Bromley,1991).

Zoophycus briantius Massalongo (1855) (Fig. 5d)is a helicoidal trace with a circular to elliptical outline.It has a depressed apex in the center,forming a cone,from which distinctive spreite extends to the burrow margin. Primary laminae are distinguishable. The marginal tube is absent.In sectional view,it appears as a continuous meniscate lamina.

Zoophycus villae Massalongo (1855) (Fig. 5e)consists of a fan-shaped region of radiating arcuate laminae, branching at an acute angle. The marginal tube is absent. Few specimens show bulging at the end. The cross-section exhibits major and minor laminae.In cross-sectional view,they are preserved as discontinuous meniscate laminae.

Zoophycus insignis Squinabol (1890) (Fig. 5f) is an antler-like to lobed Zoophycus showing distinct regular spreite. Primary laminae are distinct; the marginal tube is absent. Burrow fill is darker than the surrounding matrix.

4.2. Ichnofabric analysis

General comment: Characteristic tiering style in the study area is represented by sediments showing an the alternating (a) light coloured trace fossils in dark sediment (LID), (b) dark coloured trace fossils in light sediment(DIL)and(c)uniform,-contrast lacking trace fossils(Fig.6).The Bioturbation Index varies from BI-2 to BI-5, showing multiple phases of colonization,complex tiering, and multilayer tiering. No tier modifications are observed. The trace making community remains the same.

4.2.1. Ichnofabric analysis of the piped zone

Ichnofabric analysis of tiering in the piped zone reveals that Planolites occupies a shallow tier,whereas deposit-feeding ichnotaxa such as Asterosoma,Paleophycus,and Zoophycus together occupy a middle tier.Although Asterosoma and Zoophycus were first to colonize the substrate, they were quite abundant in the units containing discontinuity surfaces;these were cross-cut by deep-tier Chondrites, Thalassinoides,and Palaeophycus,which were among the last to colonize the substrate (Fig. 6b and c).

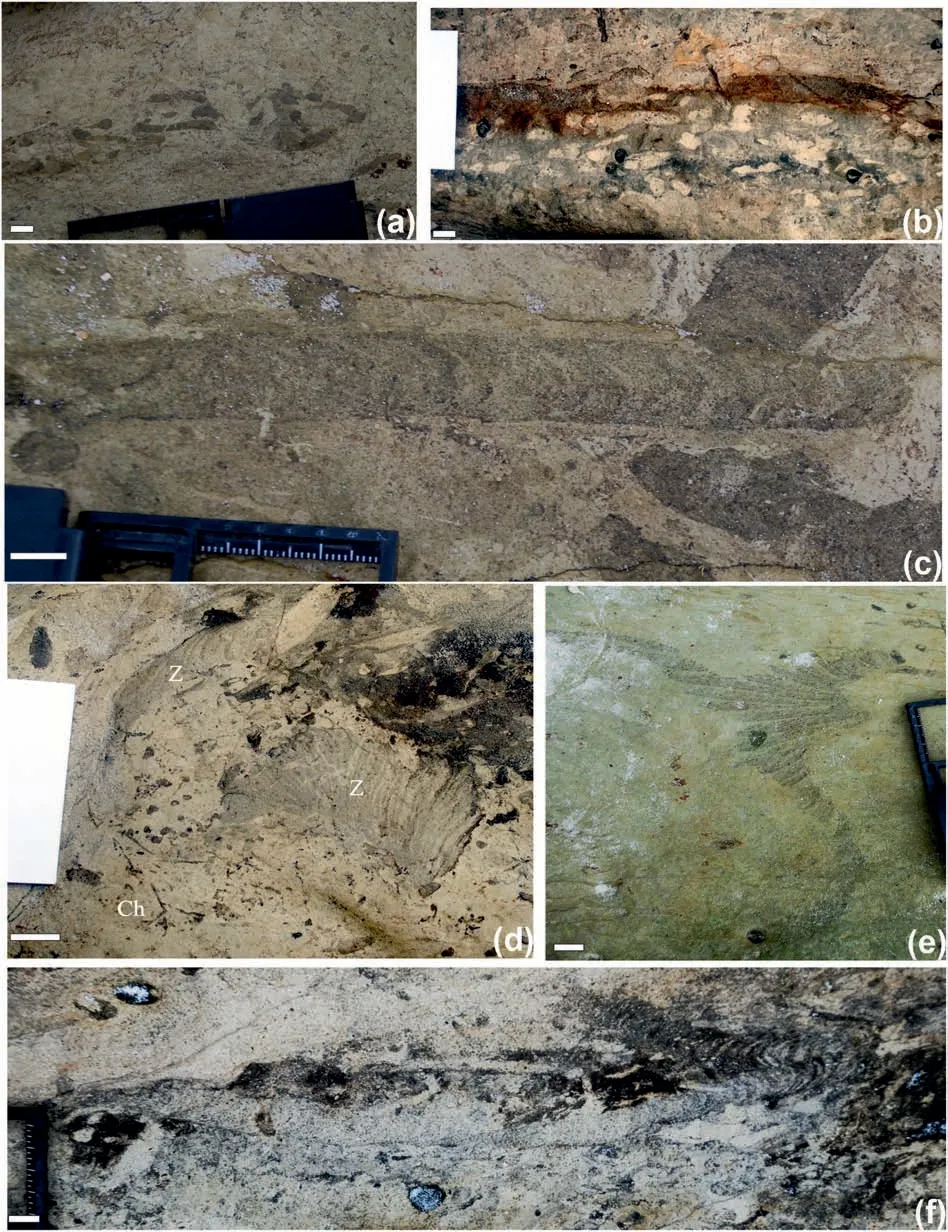

At the Kalapathar Section, the LID ichnofabric(Fig. 7) is represented by three tiers, indicated by diverse shallow tier trace fossils represented by Paleophycus tubularis, Planolites beverleyensis, and Chondrites targionii. The average maximum penetration depth of the shallow tier is up to 30 mm. The middle tier occurs around 100-120 mm penetration depth and is represented by Asterosoma isp,while the deep tier,occurring around 150 mm,is represented by Thalassinoides suevicus. In contrast, the DIL fabric seems to be more expanded and is represented by four tiers, namely shallow, intermediate, deep, and very deep. The shallow tier occurs up to a depth of 30 mm and is represented by Chondrites targionii. The intermediate tier is diverse,occurs from 40 to 110 mm of maximum penetration depth and is represented by

Fig. 7 Piped-Zone ichnofabric analysis of Kalapathar Section (As=Asterosoma; Cht = Chondrites targionii, Chi = Chondrites intricatus,Cl=Cladichnus, Pah = Paleophycus heberti, Pl-Planolites, Th=Thalassinoides, Zo = Zoophycos) a- DIL and LID ichnofabric and depth of penetration of recurring trace fossils. Note the shallow, intermediate, deep and very deep tiers and their trace fossils; b- Depth of penetration of various ichnotaxa in DIL ichnofabric, note the Chondrites occupying deepest tier and is cross-cutting all other traces; c- Depth of Penetration of various ichnotaxa in LID ichnofabric. Note absence of the very deep tier trace fossils and Thalassinoides occupying the deep tier. Note that the Thalassinoides has shifted its tier position from intermediate-deep to deep tier in the LID ichnofabric.

Cladichnus isp, Palaeophycus tubularis, Palaeophycus heberti,Planolites beverleyensis,Z.brianteus,and Z.villae. The deep tier has a maximum penetration depth of 150 mm and is represented by Asterosoma isp and Thalassinoides suevicus.The very deep tier crosscuts all the previous tiers with a maximum penetration depth up to 220 mm. In the Kalapathar succession,

Thalassinoides and Asterosoma show deepening of their tier position from their intermediate to deep tier(in DIL) to deep tier (in LID) (Fig. 7).

At Lacam Point Section(Fig.8),the LID ichnofabric is represented by condensation of the tiers,absence of shallow tiers(probably not preserved)and the middle tier represented by occasional Planolites beverleyensis occurring with a maximum penetration depth between 40 and 60 mm. The deep tier has a maximum penetration depth between 100 and 120 mm and is represented by Chondrites intricatus and Thalassinoides suevicus. In contrast, the DIL fabric lacks any discrete bed boundaries, which indicates extensive bioturbation, and homogenization of the shallow tier, the middle tier occurring between 100 and 130 mm depth and is represented by Thalassinoides suevicus. The deep tier is represented by Zoophycus brianteus and Zoophycus villae with a maximum penetration depth between 100 and 180 mm.The very deep tier Chondrites intricatus cross-cuts all the tiers and occurs between a penetration depths of 160-220 mm. In the Lacam Point section, Thalassinoides retracts its tier position from the deep tier in the DIL ichnofabric to intermediate tier in the LID ichnofabric(Fig.8).Additionally,in the LID ichnofabric only the intermediate tier is present, and shallow,deep and very deeper tiers are absent.

5.Discussion

5.1. Ichnofabrics of deep marine chalks

Fig. 8 Piped-Zone ichnofabric analysis of Lacam Point Section (Chi = Chondrites intricatus, Pl-Planolites, Th=Thalassinoides,Zo=Zoophycus),a-DIL and LID ichnofabric and depth of the penetration of recurring trace fossils.Note the complete absence of shallow tier;b-Depth of penetration of various ichnotaxa in DIL ichnofabric,note Thalassinoides occupying intermediate to very deep tier,and an overall reduction in diversity;c-Depth of penetration of various ichnotaxa in LID ichnofabric.Note the absence of trace fossils of shallow,deep,and very deep tier,and Thalassinoides occupying intermediate tier,thus shifting its tier position from deep-very deep to intermediate tier in the LID ichnofabric.

The ichnology of the nannofossil ooze and chalk is well described in several ODP/DSDP/IODP data derived from global oceans. Chamberlain (1975) well summarized the ichnology of the DSDP cores; Ekdale (1977,1978, 1980) proposed highly bioturbated and multitier ichnofabric, with deep tier trace fossils (Chondrites) colonizing sediments as deep as 20-30 cm below the sediment-water interface.Our data on the Andaman chalk also suggest that a similar assemblage occupies the deeper tiers. In the Pacific Ocean,Chamberlain (1975) summarized and analyzed 109 DSDP sites with 3000 m of cores; his compilation suggests that in the Miocene,Chondrites,composite trace fossils, Zoophycus, Teichichnus, and Helminthoida were most abundant in the Pacific Ocean data. Similarly,the ichnofabrics of the nannofossil ooze at other DSDP sites support similar tier variations as seen in the Early Miocene Andaman chalks of the present study.A highly diverse ichnoassemblage (Chondrites, Cylindrichnus, Helminthopsis, Planolites, Skolithos, Teichichnus,Thalassinoides,Trichichnus,and Zoophycus)characterizes the nannofossil ooze lithology at site 605 off the New Jersey coast (Wetzel, 1987). The analysis of the nannofossil ooze ichnofabric at site 605 indicates short-term fluctuations, with respect to the availability of nutrients,and surface productivity,and sedimentation rate along with bottom water oxygenations and deep-water circulation patterns being the drivers for the highly diverse ichnofabric (Wetzel,1987). Similar ichnofabric with highly bioturbated nano-foram chalk intervals are also well exemplified in Late Miocene IOPD cores of Site 353-U1448A taken from the Andaman sea (Clemens et al., 2015). Nanoforam ooze of Late Miocene to Early Pliocene age from ODP leg-90 sites 586,588 and 590(Nelson,1985),are highly bioturbated with Planolites, Chondrites,and Zoophycus; most of these sediments were deposited in a middle bathyal environment. Bioturbation in nannofossil oozes and chalks of the southwest Pacific do not follow the usual consensus;on the contrary,the apparent degree of bioturbation increases at those sites that are located near the boundary of contrasting water masses (Nelson, 1985), since these oceanic fronts are common regions of enhanced primary productivity in the water column.

5.2. Ichnofabrics in upwelling conditions

In the deeper ocean,especially during upwelling or high productivity, two processes are responsible for the burial of organic matter (a) a high rate of accumulation and (b) accumulation at an anoxic to dysaerobic sea floor(Pickering and Hiscott,2015,p 54).In offshore upwelling areas, the decay of the organic matter at the sea floor consumes the oxygen and makes pore water anoxic,thus creating conditions for better preservation of subsequently deposited organic matter (Summerhayes, 1983; Parrish et al., 2001 Pickering and Hiscott, 2015, p 54). Ichnologically,enhanced productivity may lead to a higher degree of diversity of trace makers willing to exploit organic-rich sediments (Rodríguez-Tovar et al., 2009).

Upwelling in the Arabian Sea is one of the betterstudied processes.It is controlled by strong monsoonal winds causing the highest productivity by bringing nutrient-rich waters to the surface to support phytoplankton blooms(Brink et al.,1998;Singh et al.,2011).Thus, phytoplankton blooms may occur under favourable sea-surface temperatures and nutrients (Smitha et al., 2014). In the South China Sea off Vietnam, ichnofabric analysis of upwelling conditions revealed an interesting pattern,whereby during summer monsoonal climate coupled with pronounced upwelling conditions,the bioturbated zone showed a 4-tiered ichnofabric.In contrast, glacial periods with weak upwelling conditions showed a decrease in ichnofabric,including trace fossil size, penetration depth and diversity (Wetzel et al., 2011). In contrast, studies of upwelling on north west African continental margin suggested diverse trace fossils resulting from stronger upwelling intensities during glacial times(Wetzel,1983).

It is well known that with decreasing bottom-water oxygenation, the rate and depth of bioturbation also decreases.In a study of the Oman margin, NW Arabian Sea, it was found that the mean diameter not the maximum penetration depth of open burrows exhibited oxygen-related patterns(Smith et al.,2000).However,another study corroborates that in the oxygen minimum zone, bioturbation decreases with increasing sediment depth (Meadows et al., 2000). The absence of bioturbation indicates severely reduced or stagnant bottom water ventilation(Schulz et al.,1996).

5.3. Inglis Formation ichnofabrics in lower bathyal palaeoenvironment

In the chalk ichnofabric of the Inglis Formation at the Kalapathar section, tiers deepen in both the LID and DIL ichnofabrics, to a penetration depth of up to 150 mm. In the LID ichnofabric, Thalassinoides and Asterosoma are ichnotaxa with a penetration depth beyond 100 mm. In comparison, the DIL ichnofabric shows a diversification of the ichnofabric with Zoophycus, Chondrites, Asterosoma, and Thalassinoides

having a penetration depth beyond 100 mm. At the Lacam Point Section,tier data show a severe reduction in the diversity and penetration depth of trace fossils.The LID ichnofabric comprises only three ichnotaxa,all having penetration depth between 70 and 100 mm,while in the DIL ichnofabric the penetration depth of Thalassinoides is distinctly deeper between 150 and 380 mm. Chondrites and Zoophycus show a penetration depth up to 200 mm. Under decreasing oxygen availability, producers of shallow tiers and of more extensive burrows get progressively eliminated, thus pushing the deeper tier dwellers to colonize shallower tiers (Savrda and Bottjer, 1989; Wetzel and Wijayananda, 1990). An increase in the sedimentation rate also mimics the effect of re-oxygenation,thus causing overprinting or destruction of earlier ichnofabric (Savrda and Bottjer, 1989). In the case of Lacam, there is no evidence of shift of deeper tiers trace fossils to shallower tiers,indicating no change in oxygenation. Preservation of traces of deeper tiers with reduced diversity indicates changes in substrate and preservation as main controlling factors.

Additionally, DIL ichnofabric (which is dark sediment-filled burrows preserved in lighter coloured sediments) suggests that most of the open burrows(Thalassinoides, Chondrites, and Zoophycus) were probably used as Cached as proposed by Bromley(1991) as one of the three possible explanations for Zoophycus. Trace makers of Zoophycus often show cache behaviour when it feeds on the surface on detritus feeder and construct the spreite as a cache for feacal pellets (Bromley, 1991; Locklair and Savrda,1998; Wetzel et al., 2011). Such cache behaviour of trace makers would occur preferably in light-coloured sediments, as they may not offer enough organic matter to feed on, and the organisms are forced to feed on detritus at or near surface, which would be abundant in the dark-coloured organic-rich sediments.Open burrows, such as Thalassinoides, are common elements of the nannofossil ooze at major DSDP sites(e.g., Droser and Bottjer, 1991). However, in older chalks, Thalassinoides dominates shelf chalks,whereas in deep water chalks Chondrites, Planolites,and Zoophycus dominate(Ekdale and Bromley,1984a).

Consequently, in both sections, the penetration depth of trace fossils within the DIL ichnofabric remains constant.This indicates that the DIL ichnofabric in Andaman sediments may not be affected by factors like oxygenation and nutrition. However, only the trace fossil diversity decreases from Kalapathar to the Lacam Point Section. In the DIL ichnofabric of Lacam Point Section,the absence of shallow tier trace fossils indicates comparatively. In the LID ichnofabric, burrowing occurred within the dark organic-rich sediments, indicating that the distribution of burrowers was controlled by the distribution of organic matter.Particularly the trace fossils Zoophycus is a deep tier trace penetrating up to 240 mm.

The sediments of the Inglis Formation are inferred to have been deposited in lower bathyal environments experiencing upwelling conditions. Chakraborty et al.(2017, 2019), while studying Miocene-Pleistocene strata from the Andaman area, indicated higher surface-water productivity and upwelling conditions during Miocene,based on the dominance of calcareous nanoplankton genera Sphenolithus and Helicosphaera.This view also supports the SEM images study of our samples from the Kalapathhar section (Fig. 2b, c),which shows abundant well-preserved foraminifers,nanoplankton, diatoms, and radiolarian indicating its deposition under higher surface water productivity and upwelling conditions (Rai, 2021; personal.communication.).The sedimentary facies of the Inglis Formation usually lacks siliciclastic turbidites and contains well-preserved calcareous microfossils. This may reflect its deposition on a topographic high above the calcite compensation depth (CCD). Based on the this discussion,the ichnofabric analysis of nano-foram oozes and chalk from various DSDP cores corroborate well with the ichnofabric data from the chalk of the Early-Middle Miocene Inglis Formation in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Thus, the studied sites offer an excellent opportunity to record the bioturbation and ichnofabric under upwelling conditions during Cenozoic times. The ichnofabric data suggest the nanoforam ooze of the Inglis Formation were deposited in the lower bathyal paleoenvironment during Early-Middle Miocene times.

6.Conclusions

Trace fossils and ichnofabric are described from thick-bedded nannofossil chalk belonging to the Lower to Middle Miocene Inglis Formation of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India. These chalks are moderately to highly bioturbated (BI-2 to BI-5) and contain several weak discontinuity surfaces in the form of ferruginous layers. The studied sections show the recurrence of ichnospecies belonging to Asterosoma,Chondrites, Ophiomorpha, Palaeophycus, Planolites,Taenidium, Thalassinoides, and Zoophycus. Ichnofabric analysis reveals multiple colonization,telescoping of the tiers and complex tiering pattern. The ichnofabric analysis suggests and supports deposition of the nanoforam ooze of the Inglis Formation in lower bathyal environment that experienced upwelling.

Availability of data and materials

All datasets cited and analyzed in this study are available in this published paper.

Funding

Self-funded.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Pandit Deendayal Energy University (PDEU) management for its support and Solar Research Department for its help with SEM Images. Author is thankful to Prof. Franz Fürsich and anonymous reviewers for their critical and insightful comments that has improved the manuscript.Author is also thankful to Mrs Seema Desai and Mr Bhairav Desai for their help in the field.

Journal of Palaeogeography2021年4期

Journal of Palaeogeography2021年4期

- Journal of Palaeogeography的其它文章

- Mineralogy and geochemistry of siliciclastic Miocene Cuddalore Formation, Cauvery Basin,South India: Implications for provenance and paleoclimate

- Sedimentary environment and model for lacustrine organic matter enrichment:lacustrine shale of the Early Jurassic Da'anzhai Formation, central Sichuan Basin, China

- Devonian reef development and strata-bound ore deposits in South China

- Hyperpycnal littoral deltas: A case of study from the Lower Cretaceous Agrio Formation in the Neuqu′en Basin, Argentina

- Sedimentological and microfossil records of modern typhoons in a coastal sandy lagoon off southern China coast

- Evidence for fault activity during accumulation of the Furongian Chaomidian Formation(Shandong Province, China)