New occurrences of Altingiaceae fossil woods from the Miocene and upper Pleistocene of South China with phytogeographic implications

Lu-Liang Huang , Jian-Hua Jin ,*, Cheng Quan ,Alexei A. Oskolski

a State Key Laboratory of Biocontrol and Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Plant Resources, School of Life Sciences, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou 510275, Guangdong Province, China

b State Key Laboratory of Palaeobiology and Stratigraphy, Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology,CAS, Nanjing 210008, Jiangsu Province, China

c School of Earth Science and Resources, Chang'an University, Xi'an 710054, Shaanxi Province, China

d Department of Botany and Plant Biotechnology, University of Johannesburg, Auckland Park 2006,Johannesburg, South Africa

e Komarov Botanical Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Prof.Popov Str. 2,St. Petersburg 197376,Russia

Abstract Mummified fossil woods of Liquidambar from the Miocene of the Guiping Basin of Guangxi and the upper Pleistocene sediments of the Maoming Basin of Guangdong,South China are recognized as the new species Liquidambar guipingensis sp.nov.and the extant species Liquidambar formosana Hance,respectively.The fossil wood of L.guipingensis shows the greatest structural affinity to the extant species Liquidambar excelsa(Noronha)Oken,which is widespread from SW China and NE India(Assam)through Myanmar and Malaysia to Indonesia.The finding of L.guipingensis may be considered as evidence for the early diversification of this lineage that occurred at least partly outside the modern range of this extant species.The fossil wood of L.formosana from the Maoming Basin represents the only Pleistocene megafossil of Altingiaceae known to date,and provides confirmation for its presence in the interglacial vegetation of South China prior the Last Glacial Maximum.

Keywords Altingiaceae, Fossil wood, Miocene, Late Pleistocene, South China

1.Introduction

The family Altingiaceae Horan.has been traditionally divided into three genera, i.e., Liquidambar L.(with a temperate and subtropical distribution in Asia and North America); Altingia Noronha and Semiliquidambar H.T.Chang(endemic to tropical and subtropical Asia)(Judd et al.,2002;APG,2003).However,based on phylogenetic analyses of Altingiaceae,Altingia and Semiliquidambar are nested within Liquidambar (Wu et al., 2010; Ickert-Bond and Wen, 2013).Thus,Liquidambar sensu lato is now a monotypic genus of Altingiaceae (Ickert-Bond and Wen, 2013). This family consists of ca.15 species,and displays a classic Asia/North America intercontinental biogeographic disjunction(Fig.1).It is distributed within temperate to tropical montane rainforests of the Northern Hemisphere, with one species in eastern North America to Central America (Liquidambar styraciflua L.), one species in western Asia (the Mediterranean, Liquidambar orientalis Mill.),and other 13 species in eastern Asia(Ickert-Bond and Wen,2013).

Fossil records of Altingiaceae have been widely reported from all over the Northern Hemisphere (mainly from mid-low latitude areas) (Fig. 1), and the earliest reliable fossil records of this family can be dated back to the Late Cretaceous in USA,North America,i.e.,fossil leaves of Liquidambar fontanella Brown and in

florescences of Microaltingia apocarpela Zhou, Crepet et Nixon (Brown, 1933; Zhou et al., 2001). Fossils of Altingiaceae are also known from the Paleocene to Pliocene oftheUSA and Canada(Felix,1884;MacGinitie,1941; Chaney and Axelrod, 1959; Prakash and Barghoorn, 1961; Hoxie, 1965; Roy and Stewart, 1971;Meyer and Manchester,1997;Melchior,1998;Pigg et al.,2004; Wheeler and Dillhoff, 2009; Stults and Axsmith,2011). In Europe, the earliest fossils of this family are leaves of Liquidambar palaeocenica Chandler,from the Paleocene of England (Chandler, 1961), while other fossils have been reported from the Eocene to Pliocene of Germany (Mai and Walther, 1978; Gottwald, 1992),Poland (Kohlman-Adamska et al., 2004), Bulgaria(Palamarev et al.,2005),Turkey(Akkemik et al.,2016),and Austria (Kovar-Eder et al., 2004), etc. In Asia, the most ancient fossils of Altingiaceae come from the Paleocene of the Kamchatka Peninsula, Russia, i.e.,leaves of Liquidambar miosinica Hu et Chaney(Maslova,1995);other fossil records are derived from the Eocene to Pliocene of China, Japan, Russia, India, and Kazakhstan (Watari, 1943; Endo, 1968; Huzioka, 1974;WGCPC, 1978; Suzuki and Hiraya, 1989; Zhilin, 1989;Agarwal,1991;Suzuki and Watari,1994;Maslova,1995,2003; He and Tao, 1997; Manchester et al., 2005; Xiao et al., 2011; Cheng et al., 2013; Maslova et al., 2015,2019). On the whole, the above fossil records of Altingiaceae are confined to the Paleogene and Neogene of mid-high latitude areas, i.e., Europe, USA, Russia and North China, whereas there are relatively few fossils from low latitude areas and no megafossils of Altingiaceae known from the Quaternary.

Fig. 1 Distribution of some modern and megafossil records of Altingiaceae.

In this paper, we describe well-preserved mummified fossil woods from the Miocene of the Guiping Basin,Guangxi and the upper Pleistocene sediments of the Maoming Basin, Guangdong, South China. These fossil woods can be convincingly recognized as a new species Liquidambar guipingensis sp. nov. and the extant species Liquidambar formosana Hance on the basis of detailed comparison with similar modern and fossil woods. The new occurrences of Altingiaceae from the Miocene and upper Pleistocene of South China enrich the fossil records of this important angiosperm family, fill a gap in the Quaternary megafossil record of Altingiaceae, and shed light on the phytogeographic history of this family.

2.Material and methods

2.1. Material

The well-preserved mummified fossil wood specimens investigated here were collected from two localities in the Erzitang Formation of the Guiping Basin,Guangxi (23°23′09.67′′N, 110°09′55.21′′E), and the upper Pleistocene sediments of the Maoming Basin,Guangdong (21°52′47.5′′N; 110°40′06.3′′E; Fig. 2),South China.

The first locality is in Xunwang county, Guiping,Guangxi (Fig. 2). The fossil wood samples were collected from the Erzitang Formation of the Guiping Basin, which consists of thin-bedded terrestrial sediments, mainly composed of brownish red,yellow,and gray mudstones deposited in lacustrine and swamp environments (Fig. 3a and b). In addition to the fossil woods,abundant plant leaves,3D-preserved fruits and seeds, and sterile and fertile fern fronds have also been discovered from these sediments. According to an associated mammal fossil of Prolipotes yujiangensis Zhao and Quercus leaves from the Erzitang Formation,the geological age of the formation is designated as Miocene (Zhao, 1988).

Fig. 2 Map of the fossil localities (red star) (base map from d-map: https://d-maps.com/). The inset map of China is modified after the Standard Map Service of the National Administration of Surveying, Mapping and Geoinformation of China (http://bzdt.ch.mnr.gov.cn/) (No.GS(2019)1825).

Fig.3 Geological setting of the Guiping(a,b)and Maoming(c,d)mummified woods localities.a Stratigraphic section of the Guiping fossil site.The girl in pink is 1.6 m tall;b Lithological column of the Miocene Erzitang Formation in Guiping;blue arrow indicates the position of the fossil wood;c Lithological characteristics of the upper Pleistocene sediments in Maoming in detail;the unconformity boundary between the upper Pleistocene sediments and the Huangniuling Formation is marked by a red dashed line.Hammer length=30 cm;d Lithological column of the upper Pleistocene unit in Maoming; blue arrow indicates the position of the fossil wood. c and d were modified from Huang et al.(2021).

The second locality is in Zhenjiang town,Maoming,Guangdong (Fig. 2). The fossil wood samples were collected from the upper Pleistocene sediments of the Maoming Basin.The fossil woods lay unconformably on the upper Eocene Huangniuling Formation, with an angular unconformity of approximately 15°(Fig. 3c).The wood-bearing layer is mainly composed of yellow,gray,and black mudstones,grayish-yellow and grayishwhite fine sandstones, with gravel sandstone (Fig. 3c and d). The geological age of this layer is the late Pleistocene (29-27 ka BP) based on accelerator mass spectrometry14C dating (Huang et al., 2021).

2.2. Anatomical examination of fossil woods

Due to the mummification of the fossil woods,they could be processed and sectioned using the same methods as used for modern woods (Lin, 1993). To soften them for sectioning with a microtome(RM2245;Leica,Nussloch,Baden-Württemberg,Germany),they were boiled in water for 12-24 h and soaked in a mixture of ethanol and glycerol (2:1) for more than 2 days. After the three sections (cross section, tangential section, and radial section) had been made, they were examined with a light microscope(AxioScope A1;Zeiss, Oberkochen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany).Wood anatomical measurements and anatomical terminology used for the descriptions in this paper follow the recommendations of the International Association of Wood Anatomists(IAWA)list of Microscopic Featuresfor Hardwood Identification(IAWA Committee, 1989). Interannual variation in growth rate was estimated by the mean sensitivity (MS) indicator calculated as the mean proportional change from each measured growth ring width to the next one.The values of MS range from 0 to a maximum of 2. High mean sensitivity(MS ≥0.3)reflects either considerable fluctuations in water supply or changes in the local growth environment for individual trees (Fritts, 1976;Parrish and Spicer, 1988). The taxonomic position of fossil woods was determined by comparison to similar modern and fossil wood structures. The comparative work is based on reference materials,particularly the computerized InsideWood database (InsideWood,2004-onwards), within which we searched for similar modern and fossil woods by entering an IAWA feature number followed by the coding letters such as p (present) and a(absent).

3.Results

3.1. Liquidambar guipingensis Huang, Jin,Quan et Oskolski sp. nov. (Fig. 4)

Family Altingiaceae Horan.

Genus Liquidambar L.

Species Liquidambar guipingensis Huang, Jin,Quan et Oskolski sp. nov.

Holotype GPW016.

Paratype GPW014.

Repository The Museum of Biology, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, China.

Stratigraphic horizon and age Erzitang Formation,Miocene.

Etymology The specific epithet is named after the Guiping Basin,where the fossil was found.

Diagnosis Wood diffuse-porous with vessels solitary or in groups.Perforation plates exclusively scalariform with less than 20 bars.Intervessel pits scalariform and transitional to opposite. Helical thickenings absent.Axial parenchyma diffuse. Rays 1-4 (−6)-seriate,heterocellular. Vessel-ray pits with much reduced borders to apparently simple: mostly scalariform.Prismatic crystal present in ray cells. Axial intercellular canals of traumatic origin in long tangential lines.

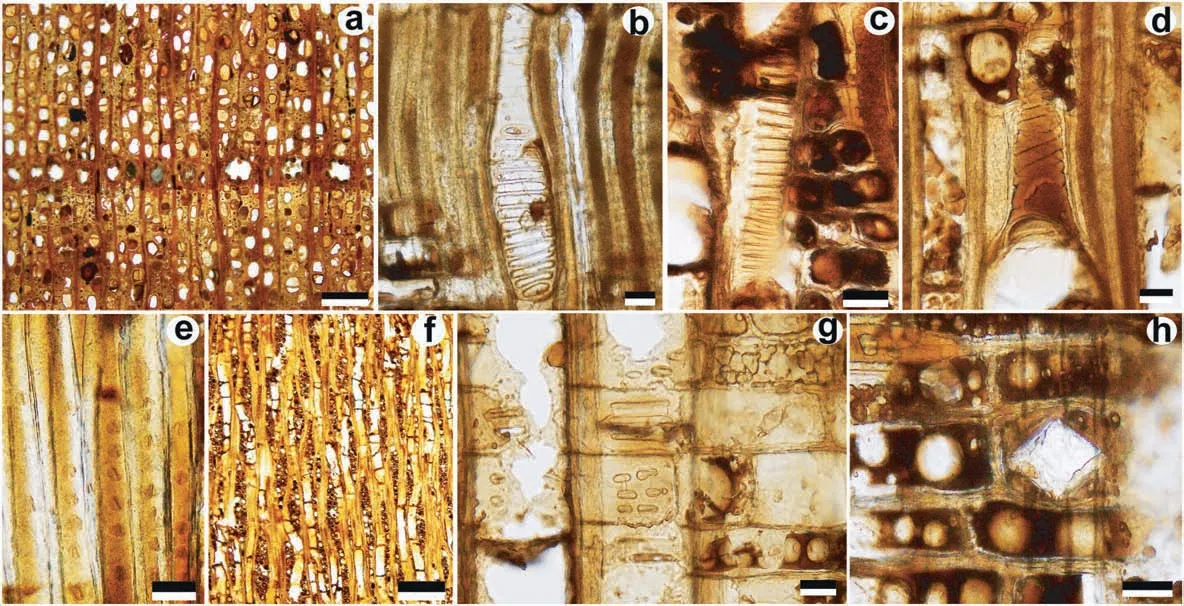

Description Woods are diffuse-porous (Fig. 4a and b) with indistinct or absent growth rings (Fig. 4a and b). The growth ring width in GPW016 varies between 0.21 and 1.33 mm (MS = 0.32; n = 25). Vessels are evenly distributed,angular to round in outline,solitary(30%) and 2-4 in a group; tangential diameters 24-66 μm (mean 36.6 ± 1.48 μm), radial diameters 24-62 μm (mean 45.4 ± 1.36 μm); vessel frequency 120-187 per sq.mm (mean 164 per sq.mm). Perforation plates are exclusively scalariform with 4-17 bars(Fig.4c).Intervessel pits bordered,elliptical to mainly horizontally elongated,scalariform and transitional to opposite,with elliptical margins and slit-like apertures(Fig.4c and d).Helical thickenings on vessel walls are absent. Fibers are non-septate, oval, square, or polygonal in cross section, 4-17 μm (mean 8.9 ± 0.46 μm) in tangential diameter, walls thin to medium thick; with distinctly bordered pits 4.4-7.4 μm in diameter on radial walls(Fig.4e).Axial parenchyma rare and diffuse, without prismatic crystals (Fig. 4a). Rays 1-4 (−6)-seriate (Fig. 4f); heterocellular,with procumbent ray cells in ray body and 1-3 rows of marginal square or upright cells; rays are 46-948 μm (mean 383.1 ± 41.17 μm) in height; ray frequency 11-16 per mm. Vessel-ray pits with much reduced borders to apparently simple, elliptical to horizontally elongated,scalariform and transitional to opposite, 6.2-25.5 μm wide (Fig. 4g). Prismatic crystals are observed in ray cells(Fig.4h).Traumatic axial canals arranged in long tangential lines are present in two of the 25 growth rings (Fig. 4b) studied.

Comparison with modern woods The combination of diffuse-porous wood, exclusively scalariform perforation plates, predominantly scalariform intervessel pitting, vessel-ray pits with much reduced borders to apparently simple:predominantly scalariform,diffuse axial parenchyma, and axial intercellular canals of traumatic origin (InsideWood search: 5p 14p 20p 32p 76p 131p with 0 allowable mismatches)occur only in the extant woods of Altingiaceae(InsideWood,2004-onwards). The occurrence of traumatic axial intercellular canals arranged in long tangential lines is one of the most distinctive traits found in this family(Wheeler et al., 2010). Unlike the fossil woods, all modern species of Altingiaceae except Liquidambar excelsa (Noronha) Oken (= Altingia excelsa Noronha)share the presence of helical thickenings on vessel walls.Thus,L.excelsa shows the greatest similarity to the Miocene woods, but it differs from the latter in having narrower (≤4-seriate) rays, as well as lower vessel frequency(48 per sq.mm)and a high proportion of solitary vessels (>74%) (Cheng et al., 1992;InsideWood, 2004-onwards; Wheeler et al., 2010).Thus, the fossil woods from Guiping Basin are very similar to the extant genus Liquidambar,but it cannot be convincingly placed into any of its modern species described to date by wood anatomists.

Comparison with other fossil woods Among fossil woods reliably ascribed to Altingiaceae to date (Table 1), axial intercellular canals of traumatic origin have been reported in Liquidambar hisauchii(Watari)Suzuki et Watari from the lower Miocene of Japan, in Liquidambar sp. from the Pliocene to Miocene of Japan(Watari, 1943; Suzuki and Hiraya, 1989; Suzuki and Watari, 1994), and in Liquidambar sp. from the Paleogene and middle Miocene of USA (Prakash and Barghoorn, 1961; Melchior, 1998; Wheeler and Dillhoff, 2009). L. hisauchii and Liquidambar sp. from Japan differ from the fossil wood under study in having helical thickenings on vessel walls, narrow rays and more bars on the scalariform perforation plates (up to 40 bars). Liquidambar sp. from the middle Miocene of USA can be distinguished from the Guiping fossil wood by its lack of prismatic crystals in rays, having helical thickenings on vessel walls, and bordered vessel-ray pits. Liquidambar sp. from the Paleogene of USA shows close similarity with the Guiping fossil wood,but the former lacks the prismatic crystals in rays.

Fig.4 Wood structure of Liquidambar guipingensis sp.nov.(GPW016).a Transverse section(TS),diffuse-porous wood without growth rings;vessels solitary and mostly in small multiples (2-4); b TS, tangential line of traumatic axial secretory canals; c Tangential section (TLS),scalariform perforation plate with 11 bars;intervessel pits are scalariform and transitional to opposite;d TLS,intervessel pits are scalariform and transitional to opposite;e TLS,distinctly bordered pits on the walls of fibers;f TLS,rays 1-4(−6)-seriate;g Radial section(RLS),vesselray pits with borders much reduced to apparently simple,scalariform and transitional to opposite,elliptical to horizontally elongated;h RLS,the prismatic crystals present in rays. Scale bars: a, b, f 200 μm; c 50 μm; d, e, g, h 20 μm.

Fig. 5 Wood structure of Liquidambar formosana Hance from Maoming (MMHW013). a Diffuse-porous wood with indistinct growth rings;vessels solitary and multiples (2-4); axial secretory canals in tangential row, TS; b Perforation plates scalariform with 15 bars, RLS; c Scalariform intervessel pits,TLS;d Helical thickenings on vessel element tail,RLS;e Non-septate fibers with distinctly bordered pits,RLS;f 1-3(−4)-seriate rays,TLS;g Vessel-ray pits apparently simple,scalariform and transitional to opposite,elliptical to horizontally elongated,RLS; h Prismatic crystal in rays, RLS. Scale bars: a, f 200 μm; b-e, g, h 20 μm.

Table 1 Comparison of anatomical traits of Liquidambar guipingensis sp.nov.and other extinct Altingiaceae wood.+=present;-=absent;?=no data;VF=Vessel frequency;NB=Number of bars on the scalariform perforation plates;HT=Helical thickenings;RW=Rays width;VRP=Vessel-ray pits:B=Bordered,S=Much reduced borders to apparently simple;PC=Prismatic crystals in rays; AC= Axial intercellular canals of traumatic origin.

In summary, the fossil samples under study can be ascribed to the genus Liquidambar; however, they cannot be convincingly placed into any extant or extinct species of this genus. Therefore, we assigned the wood sample from Guiping Basin to the genus Liquidambar as a new species, Liquidambar guipingensis sp. nov.

3.2. Liquidambar formosana Hance (Fig. 5)

Family Altingiaceae Horan.

Genus Liquidambar L.

Species Liquidambar formosana Hance.

Samples MMHW013, MMHW017, MMHW050.

Repository The Museum of Biology, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, China.

Stratigraphic horizon and age The upper Pleistocene sediments of Maoming Basin, Guangdong Province, South China; late Pleistocene.

Description Woods are diffuse-porous with indistinct growth rings (Fig. 5a). The growth ring width in MMHW013 varies between 0.33 and 1.24 mm(MS = 0.34; n = 22). Vessels are angular to round in outline, solitary (58%) and 2-3 in a group; tangential diameters 19-54 μm (mean 39.0 ± 0.89 μm), radial diameters 21-75 μm(mean 48.4 ± 1.53 μm); the wall of vessel is thin being 1.7-3.9 μm in thickness; vessel frequency 177-193 per sq.mm(mean 184 per sq.mm).Perforation plates are exclusively scalariform with 7-20 bars (Fig. 5b). Intervessel pits bordered, mostly scalariform and transitional to opposite,with elliptical margins and slit-like apertures (Fig. 5c). Helical thickenings are commonly present on the walls of vessel tails (Fig. 5d). Fibers are non-septate, oval or polygonal in cross section, 10-27 μm (mean 17.4 ± 0.56 μm) in tangential diameter, walls thin to medium thick (2.1-6.6 μm in thickness); with distinctly bordered pits of 3.0-6.4 μm in diameter on radial walls(Fig.5e).Axial parenchyma is diffuse,very scanty(Fig.5a).Rays 1-3(−4)-seriate;heterocellular,with procumbent ray cells in ray body and 1-2 (−5)rows of marginal square or upright cells; rays are 77-943 μm (mean 340.6 ± 31.52 μm) in height; ray frequency 12-16 per mm(Fig.5f).Vessel-ray pits with much reduced borders to apparently simple, scalariform and transitional to opposite, elliptical to horizontally elongated, 7.6-33.4 μm in horizontal size(Fig. 5g). Prismatic crystals are often observed in ray cells(Fig.5h).Traumatic axial canals arranged in long tangential lines are present in two of the 22 growth rings observed (Fig. 5a).

Comparison with modern woods The fossil woods from the Maoming Basin are similar in structure to the samples from the Miocene of the Guiping Basin,sharing the presence of diffuse-porous wood, exclusively scalariform perforation plates, predominantly scalariform intervessel pitting,mostly scalariform vessel-ray pits with much reduced borders, diffuse axial parenchyma, axial intercellular canals of traumatic origin,and prismatic crystals. However, unlike the Guiping fossil woods,the samples from the Maoming Basin have narrower(up to 4-seriate)rays and helical thickenings on the vessel wall.The combination of the above wood traits confirms a close affinity of the fossil woods from Maoming Basin to the extant woods of Altingiaceae(InsideWood, 2004-onwards; Wheeler et al., 2010).

Among modern species of Altingiaceae, the occurrence of traumatic secretory canals has been reported in Liquidambar excelsa (Noronha) Oken (synonym

Altingia excelsa Noronha), L. formosana Hance, L.orientalis Mill. and L. styraciflua L. (Yatsenko-Khmelevsky, 1954; Cheng et al., 1992; InsideWood,2004-onwards; Wheeler et al., 2010). However, the fossil wood from the Maoming Basin is distinct from that of L. excelsa in having helical thickenings on vessel walls, and differs also from L. orientalis and L.styraciflua in the occurrence of crystals in ray cells.Thus, the sample under study shows the greatest similarity to L. formosana. Although some data(InsideWood, 2004-onwards; Wheeler et al., 2010)suggest that L. formosana has narrower (1-2-seriate)rays than the wood from the Maoming Basin, the occurrence of 3-4-seriate rays in L. formosana has been reported by Cheng et al. (1992). Therefore, the fossil wood under study can be ascribed to this extant species.

Comparison with other fossil woods Within the fossil woods reported worldwide and assigned to Altingiaceae (Table 1), the fossil wood from the Maoming Basin shows the closest similarity with Liquidambar hisauchii (Watari) Suzuki et Watari,Liquidambar sp. from the Pliocene and Miocene of Japan (Watari, 1943; Suzuki and Hiraya, 1989; Suzuki and Watari, 1994), Liquidambar sp. from the Paleogene and middle Miocene of USA (Prakash and Barghoorn, 1961; Melchior, 1998; Wheeler and Dillhoff, 2009), and Liquidambar guipingensis sp.nov. from the Miocene of Guiping Basin (this study).Unlike the fossil wood from the Maoming Basin, the Paleogene Liquidambar sp. from USA lacks prismatic crystals in rays and has distinctly bordered vessel-ray pits, and the middle Miocene Liquidambar sp. from USA lacks helical thickenings on vessel walls, whereas L. guipingensis sp. nov. from the Guiping Basin has wider rays (up to 6-seriate) and lacks helical thickenings. L. hisauchii, Liquidambar sp. from the Pliocene and Miocene of Japan shows the closest resemblance to the fossil woods from the Maoming Basin, but has more bars on scalariform perforation plates (up to 40) than the upper Pleistocene Maoming fossil woods.

In summary, the fossil woods from the Maoming Basin show the closest similarity with the genus Liquidambar, especially L. formosana Hance, which is not significantly different to the fossil wood under study, and the fossil woods from the Maoming Basin cannot be ascribed to any other reported fossil woods deemed to represent Liquidambar. We therefore assigned the wood samples from the Maoming Basin to

L. formosana Hance.

4.Discussion

formosana(0.34)likely reflects relatively minor annual variation in water supply as well as other weak environmental stress factors influencing growth for those individual plants. Noteworthy is that the sample of L.formosana shows the same sensitivity as Keteleeria sp.,which is also found in the upper Pleistocene deposits of the Maoming Basin (Huang et al., 2021). Growth ring analyses of more representative sampled fossil woods from localities in the Guiping and Maoming basins are required, however, for more reliable estimations of local fluctuations of their paleoenvironments.

Liquidambar guipingensis sp.nov.from the Miocene deposits within the Guiping Basin, Guangxi, shows the greatest structural affinity with the extant L. excelsa(synonym Altingia excelsa), the only species of Altingiaceae lacking helical thickenings on the vessel walls.L. excelsa is widespread from SW China (SE Xizang, SE Yunnan) and NE India (Assam) through Myanmar and Malaysia to Indonesia (Vink, 1957; Zhang et al., 2003;Ickert-Bond and Wen, 2013), but the Guangxi material lies outside this distribution range. L. excelsa is confined to mixed mountain forests occurring across a broad elevation range,i.e.,between 200 and 2200 m in the Eastern Himalaya (Behera and Kushwaha, 2007).Based on molecular dating,L.excelsa is thought to have arisen in the Oligocene (Ickert-Bond and Wen, 2006;Bobrov et al.,2020).The fossil wood of L.guipingensis sp.nov.may be considered as an evidence for the early diversification of this lineage that occurred at least partly outside of the modern range of L.excelsa.

While the fossils of Altingiaceae have been found widely across the North Hemisphere from the Late Cretaceous to Pliocene (see Introduction for review),only fossil pollen evidence has been reported for the Quaternaryhistoryofthisfamily.To date,thefossilwood of L.formosana from the Maoming Basin represents the only Pleistocene megafossil of Altingiaceae.Our previous data(Huang et al.,2021)suggest thatat 29-27 ka BP in the Maoming Basin this species co-occurred with the conifer Keteleeria sp.in a mixed forest influenced by a humid summer-monsoon climate. Fossil pollen of L.formosana has been reported from coeval deposits of the Leizhou Peninsula in Guangdong Province(Zheng and Lei, 1999). Our finding of the fossil woods from the Maoming Basin attributable to this species provides additional confirmation for its common presence in the interglacial vegetation of South China prior the Last Glacial Maximum(26-20 ka BP).

Moderate mean sensitivity exhibited in the fossil woods of L. guipingensis sp. nov. (0.32) and L.

5.Conclusions

The new fossil wood species Liquidambar guipingensis sp.nov.is described from the Miocene of the Guiping Basin of Guangxi, South China. Showing structural affinity to the extant species L. excelsa ranging from SW China through SE Asia to Indonesia.The new finding provides evidence for the early diversification of this lineage that occurred at least partly outside the modern range of L. excelsa.

The finding of mummified fossil wood of Liquidambar formosana Hance in the upper Pleistocene sediments of the Maoming Basin of Guangdong indicates the presence of this species in the interglacial vegetation of South China prior to the Last Glacial Maximum.

The fossil woods of L. guipingensis sp. nov. and L.formosana exhibit a moderate mean sensitivity (0.32 and 0.34,respectively),which likely reflects relatively minor annual variation in water supply as well as other weak environmental stress factors influencing growth of individual plants.

Abbreviations

IAWA International Association of Wood Anatomists

MSMean sensitivity

RLSRadial section

TLSTangential section

TSTransverse section

Availability of data and material

All fossil woods are deposited in the Museum of Biology, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, China.

Funding

(1) The National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 42072020, 42102004,41820104002)

(2) China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2020M683027)

(3) State Key Laboratory of Palaeobiology and Stratigraphy (Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, CAS) (Grant No. 193118)

(4) Institutional Research Project No. АААА-А19-119030190018-1

Authors' contributions

JHJ and CQ participated in the design of the study.LLH and AAO photographed specimens and arranged the figures. LLH, JHJ and AAO conducted taxonomic treatments,and phytogeographic interpretations.LLH wrote the manuscript and formatted the text. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

Acknowledgements

We thank the University of Johannesburg and the Komarov Botanical Institute (institutional research project # AAAA-A17-117051810115-1) for financial support for AAO.We thank graduate students majoring in plant science at Sun Yat-sen University for participating in the field collection of the fossils. We are grateful to Professor Robert A. Spicer (The Open University, UK) for improvements of the English in this paper.

Journal of Palaeogeography2021年4期

Journal of Palaeogeography2021年4期

- Journal of Palaeogeography的其它文章

- Mineralogy and geochemistry of siliciclastic Miocene Cuddalore Formation, Cauvery Basin,South India: Implications for provenance and paleoclimate

- Sedimentary environment and model for lacustrine organic matter enrichment:lacustrine shale of the Early Jurassic Da'anzhai Formation, central Sichuan Basin, China

- Devonian reef development and strata-bound ore deposits in South China

- Hyperpycnal littoral deltas: A case of study from the Lower Cretaceous Agrio Formation in the Neuqu′en Basin, Argentina

- Sedimentological and microfossil records of modern typhoons in a coastal sandy lagoon off southern China coast

- Evidence for fault activity during accumulation of the Furongian Chaomidian Formation(Shandong Province, China)