遗产景观的韧性设计

——历史庄园景观保护与发展的景观导向区域设计方法

著:(荷)斯特芬·奈豪斯 (荷)保罗·西森 (荷)爱丽兹·斯托默-斯密斯 译:张清然 校:蔡佳秀

1 介绍

庄园景观遗产中的区域景观特征是由多个历史乡村庄园决定的[1],例如历史悠久的城堡、乡村别墅、庄园及其附属花园、农田和森林等。庄园是塑造世界各地区域、景观与社会的强大媒介。德国、英国、比利时、意大利、法国、丹麦、葡萄牙和西班牙都有绝佳的例子,同时我们在俄罗斯、日本和中国也找到一些案例(图1、2)[2-4]。庄园及其景观的建设一直由贵族阶级控制,这种土地所有权是他们权力的基础[5]。一处土地若没有建设乡村住宅,那它几乎没有什么用处,这些乡村住宅承载着商业活动,是休闲娱乐的“发电站”。庄园景观是为联系宫廷或教皇的住所、狩猎小屋、公园和农场所设置的,贵族们通过空间设计、社会和经济的手段组织领土而彰显其权利。因此,乡村的庄园和景观之间有着直接的关系,在这里,水网与路网的建设实现了人类对于领土的掌控,同时这些交通网络实现了与城市中心更好的连接,让贵族阶级可以轻松地在城市和乡村庄园之间穿行。

1 意大利都灵附近作为区域整体景观设计一部分的皇家狞猎宫——StupinigiStupinigi, a royal hunting palace as part of a regional designed landscape near Torino, Italy

2 1810年意大利都灵庄园景观,一个区域性设计的国土系统——通过轴线组织的皇家住宅、花园、猎场和农场The estate landscape around Torino (Italy) around 1810. A regional designed territorial system of royal residences, gardens, hunting grounds and farming organised by axial road patterns

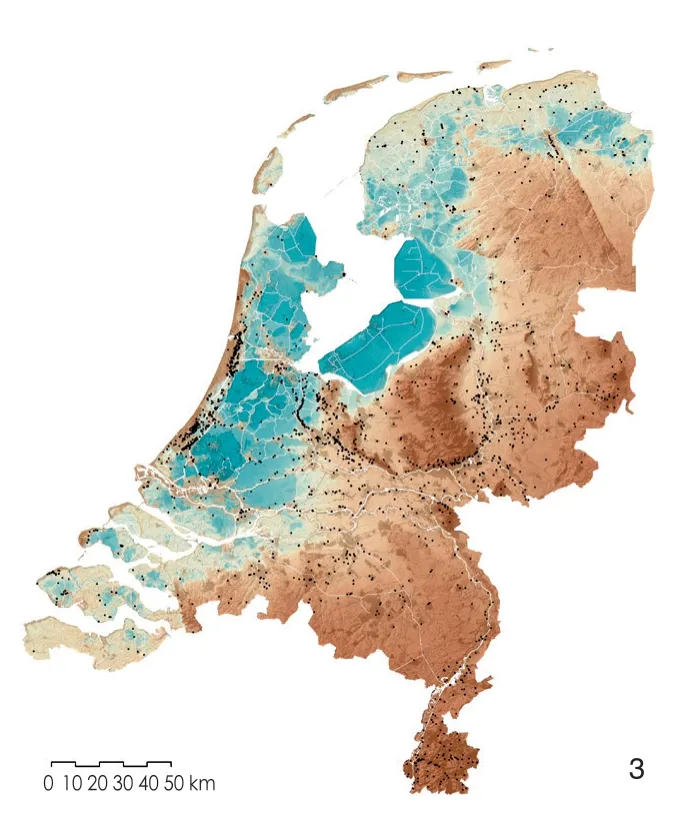

庄园景观分布在荷兰的各地(图3),其中很多修建在阿姆斯特丹(Amsterdam)和海牙(The Hague)这类大城市的周围,还有一些散落在相对偏远的荷兰北部和东部。然而,相比欧洲的其他地方,荷兰的乡村别墅和庄园的规模要小得多。例如在英国,超过1 200 hm2才称为庄园。在荷兰,大多数乡村庄园在5~200 hm2之间,很少有超过1 000 hm2的大型庄园。除了规模较小这一特征外,荷兰的庄园还具有区域意义,因为庄园景观是由地理位置相近的乡村别墅与庄园共同组成的,其景观特征与乡村别墅和庄园的外观直接相关,居民和游客也都非常珍视、喜爱这些景观。

3 荷兰的庄园的分布与地质形态特征和水网布局密切相关The allocation of the estates in the Netherlands is closely related to geomorphological features and water networks

荷兰国家遗产局已经列明了一些名胜古迹,如乡村别墅、马车房、庄园农场、茶馆、花园小品、公园和(部分)乡村庄园。在荷兰有552个经过国家认证并编辑在册的乡村庄园,被称为乡村庄园综合体。

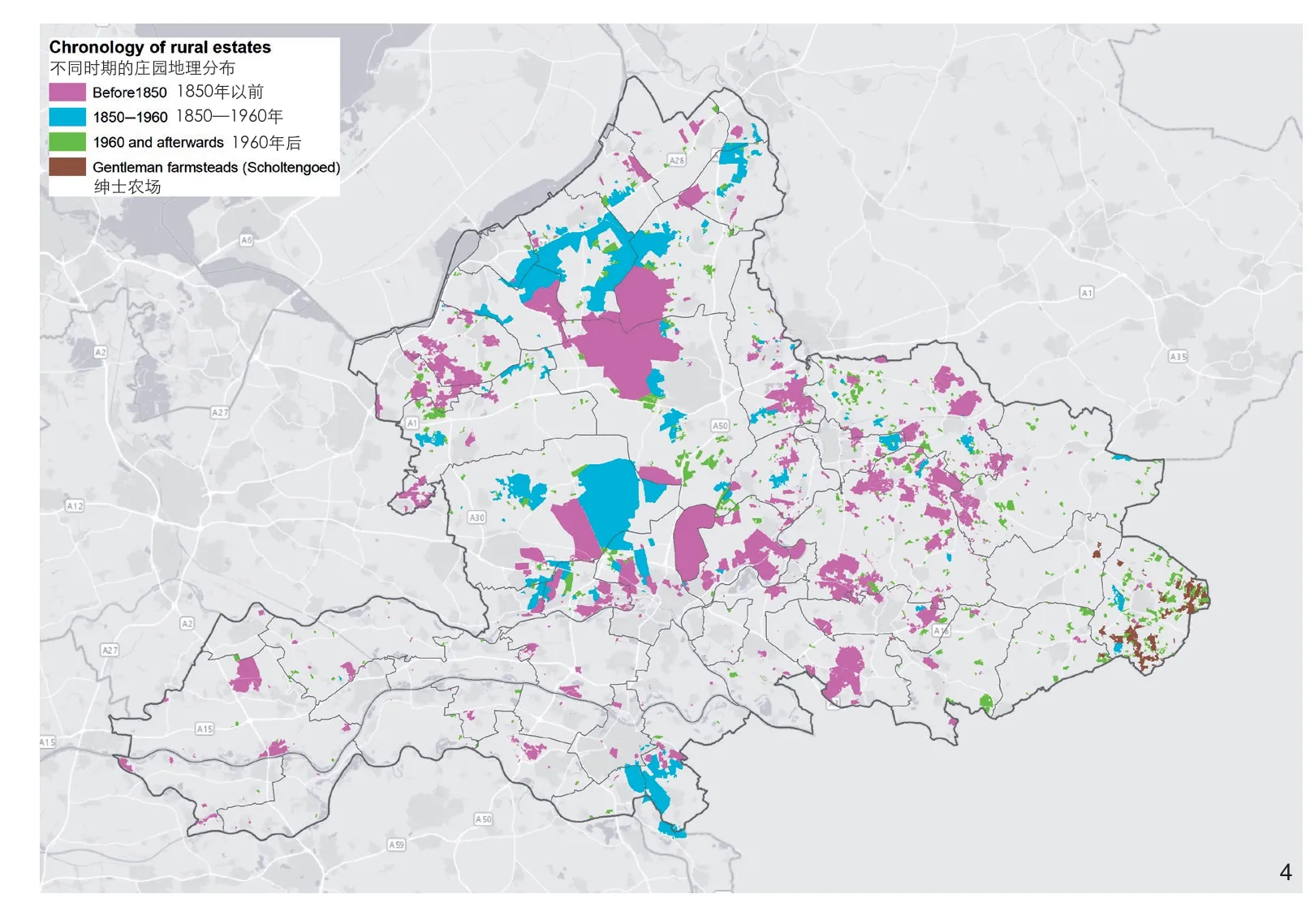

格尔德兰省位于荷兰中东部区域,面积为5 137 km2,是荷兰12个省中占地面积最大者,其包含51个自治市,共拥有200万人口,风景多样,有森林、大河和乡村。拥有国际中学和大学的阿纳姆市(Arnhem)、奈梅亨市(Nijmegen)和瓦赫宁根市(Wageningen)作为该地区的中心城市支撑起了该地的知识型经济。超过500座乡村别墅和庄园坐落于该地区(图4)。格尔德兰省拥有119个国家级乡村庄园综合体,超过全国总数的1/5。这些乡村庄园综合体中,有97个城堡和乡村别墅的主体建筑被认证为国家名胜古迹。

4 格尔德兰历史著名乡村和庄园地图Map of known historic country and landed estates in Gelderland

自中世纪晚期以来,该地区一直深受当地精英欢迎,特别是在被称为世外桃源的格尔德兰省首府阿纳姆周围,沿着埃塞尔河(the river IJssel),即该省最东部的一个县。那里起伏的景观、河流与小溪、肥沃的土地被认为是理想的农业与公园用地。直至今日,城堡、乡村别墅和庄园仍然装点着格尔德兰,这其中有2/3仍为私人财产(图5),其他的则由信托机构(如格尔德兰信托)、国家组织、政府和商业企业所有。

5 De Wiersse——游客络绎不绝,仍为私人所有的国际知名纪念性庄园De Wiersse, a monumental estate that is still privately owned and inherits an internationally famous historical garden that attracts many visitors

这些庄园景观及其组成要素——纪念性建筑、花园和其他景观元素,具有很高的遗产价值:庄园景观之中蕴含了珍贵的自然景观,这些庄园景观更好地保留了自然和人文特色;庄园景观为旅游、休闲和运动提供了丰富的机会;庄园景观作为历史城堡、乡村别墅和庄园的聚集,具有很高的经济价值。

在遗产的保护方面,荷兰有着悠久的传统。但自20世纪30年代以来,庄园景观逐渐远离了人们的视野[1],人们更关注纪念碑般的建筑,而不是在景观环境中的建筑。但为了可持续地保护和发展城堡、乡村别墅和庄园,在景观环境中认知它们是至关重要的。这需要将单个乡村别墅与其周边环境——花园、公园、庭园联系起来作为整体对待,也需要在一个区域范围内,综合考量多个乡村别墅的整体环境及它们之间的关系。在历史景观中,城堡、乡村别墅等建筑物与其附属功能空间如马棚、花园等与大地景观交织在一起,它们以大地景观作为本底,并依托大地景观的空间、美学属性,塑造空间序列,实现独特的视觉效果;反之,这些建筑物及其附属功能空间也为大地景观带来新的美学与功能价值[1]。

气候变化对庄园景观的水资源管理有显著影响,特别是水资源的丰裕和短缺,以及由于气温升高引起的植被变化。与此同时,持续的城市化与人类日益增长的休闲需求也给庄园景观带来了空前的压力。如何应对由城市化带来的空间碎片化问题,以及如何回应不可避免的因休闲旅游需求的增加而带来的庄园产权转换和功能置换等问题,是现如今庄园景观面临的巨大挑战。本文作者认为,这些挑战的复杂性需要从区域或“直升机”视角来理解,同时也需理解庄园之间的内涵和系统性关系,从而找到各利益相关方可协作的平台。本研究提出的基于景观的区域设计方法通过跨尺度的设计研究与设计思维,解读和认知景观的空间结构与空间连贯性,并依托这些空间特征和空间组织逻辑探讨乡村别墅的未来发展。然而,我们应如何从空间的角度来理解庄园景观呢?我们该如何应用这些知识来保护以及适用其未来呢?

2 作为文化景观的庄园景观

庄园景观不仅是投资、享乐的对象或权力的表达,而且是真正意义上的文化景观。由欧洲委员会界定的文化景观的标准定义是:“一个被人们感知的区域,其特征是自然或人为因素作用或两者相互作用的结果。[6]”定义强调了2个方面:1)景观是人类与环境互动的结果;2)景观的动态本质——无论有无人为干预,景观都会发生变化,这些变化有时影响深远,有时影响较小,比如气候变化影响的后果,需要很长时间才能显现出来。而一些变化也可以迅速发生,比如在原农业地区开发新的住房建造项目。

这就是为什么景观可以被视为一个复杂的动态系统,这个系统由众多相互作用、动态变化的子系统组成。这些子系统时刻动态回应自然变化、社会需求以及技术的发展。从这个角度来看,我们应该把庄园景观理解为自然和社会的界面,是两个子系统结构与进程的外在表现形式。

一种实用且已被广泛应用的方法是对景观进行分层分析,将不同要素置于不同的图层中,并探讨不同分层之间的互动关系。分层的依据是这些要素在时间维度上演进变化的频率,以及这些要素在变化时对建成环境的影响[7]。逐层拆解庄园景观是把握不同系统和子系统及其关系的一种方式,这种划分不应该被看作是一种静态的或单纯的分层安排;相反,这些分拆的层次和子系统是一个或多或少会相互影响的离散层,也可能伴随着时间的变化发生改变。在这里,了解庄园景观及其起源——物理环境(硬件)、人类活动(软件)、文化、制度和概念性理念之间的关系被认为是必不可少的[8](图6)。

6 哈克福特周围的庄园景观,一个历史悠久的“分层”文化景观的案例,是人类及与自然环境互动的产物The estate landscape around Hackfort, a centuries-old layered cultural landscapes as a product of the action and interaction of humans with their natural environment

2.1 自然环境层

自然环境是地形、水、土壤、地质基础结构和气候,及其相互关联的子生态系统。自然环境不应被视为由多个离散的因素组合起来的系统,而应被视为核心和不可分割的组成部分,它决定了景观应如何被对待。这一主要条件(即自然环境)的动态特点是缓慢的,通常察觉不到其演变、重复迭代以及自然循环的过程。

2.2 人类的调整与干预层

利用自然环境进行生活、工作和娱乐是人类活动的重要组成部分。人类通过耕种、修建乡村庄园及花园、修缮道路、开凿水道等方式利用自然环境,这种利用过程有时会使景观发生一系列的剧烈变化。

2.3 文化、组织和政治层

这一层含有自然环境的文化、精神和宗教概念,以及人类与之的互动,包括科学技术的现状、组织形式、政治运动、设计理念和审美理想。例如,水在不同的文化中有不同的含义,这可以在公园和花园的景观设计处理中窥见一斑。文化、组织和政治层的变化周期相对较短,因为这与人的参与介入和政治变动相关。

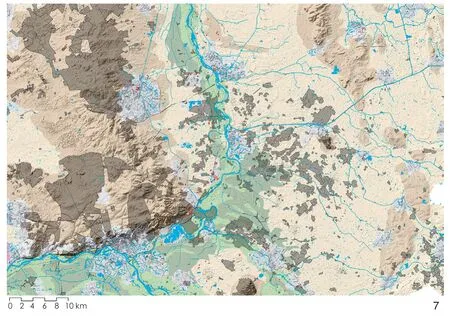

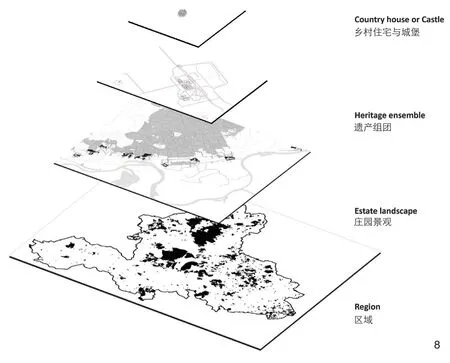

对庄园景观的理解是由各个图层及各层之间的关系所决定的(图7)。庄园景观是一种关系结构,连接并影响尺度、空间、生态、功能和社会。庄园景观是一个整体系统,是一个空间尺度体系,我们只能通过观察不同的空间尺度及其相互关系来理解。也就是说,单个的乡村别墅,连同它们的花园、公园和庭园,构成一所庄园,而多所庄园构成一处庄园景观,多处庄园景观则构成了一个区域(图8)①。因此,乡村庄园是这个尺度连续体的一部分,相互之间的关系是通过在不同尺度的环境中特定地点或位置的依附、连接和嵌入而形成的。

7 自然地形和水文与庄园景观密切相关,其决定了城堡、乡村别墅和庄园的位置和分布,以及土地使用的可能性。左边是与有关于含沙冰脊的庄园景观,中间是伊塞尔河和山谷景观,右边是覆被沙子和纵横小溪的庄园景观Estate landscapes are closely related to natural topography and hydrology, determining the location and allocation of castles, country houses and estates, and possibilities for land use. To the left the estate landscape related to the sandy ice-pushed ridge, in the centre the estate landscape of the Ijssel river and valley, and to the right the estate landscapes of cover sands and brook system

8 作为空间尺度体系的庄园景观Estate landscapes as scale-continuum

3 庄园景观的历史

时间是了解庄园景观的基本要素。随着时间的推移,庄园景观经历了基于发展可能性和价值评判的演变。部分空间结构、肌理规则和空间形态被保存下来;其他的或继续发展,或被新的形态所取代,促成了丰富的历史与空间类型演变[8]。在空间演变的过程中,那些相对稳定的景观结构与那些快速变化的空间结构之间相互制衡影响,并在演变中达到一种平衡[9]。更持久则更倾向于抗拒改变,经时间周转便会变得更“健壮”(甚至具有钝性,即与其他物质几乎没有相互反应)。而这些不同步的变化将景观变成一个分了层的整体,其由时间留下的物理痕迹或相互促进,或相互排斥[10]。

格尔德兰的庄园景观建设大致分为3个关键阶段:中世纪—1600年,贵族(有土地的精英)拥有的占据大量土地的城堡;1600—1800年,城市居民的乡村别墅和庄园;1800—1940年,金融、商业和工业精英所建造的小型乡村别墅。

这些阶段为一系列的事件提供了窗口,连接传统与当代、有形与无形。从这方面来看,一个庄园景观具有十分丰富的意义,它可以被“读”作“传记”“重写本”,阐述了促成自身形成的关键活动[11-12]。

庄园景观作为解读历史的关键是其包含的“长期”(法语:Longue durée)的概念,景观作为一个长期的结构,在“连续居住”[13-14]的过程中随着时间的推移而变化,对于这些历史痕迹的掌握是实现庄园景观更新的抓手之一,即需要在此基础上添加新的“层”。庄园景观的演变是“与生俱来的”对历史的“抹去”与“书写”。正如我们现在所看到的,庄园景观是一个渐进选择的结果,在这个过程中,一些元素被保留下来,另一些元素发生变化或被取代。

4 实现富有韧性的庄园景观

气候的变化、旅游休闲需求的增加等挑战,都需要谨慎处理应对,因为快速的空间扩张和功能置换可能会影响庄园景观的层次及其“可读性”,文化认同就有消失的危险。为了避免这种情况发生,我们需要针对变化进行管理(“变化管理”法),以创造一个能适应未来的庄园景观,让过去以某种形式继续发挥适当的作用[15]。这是一个动态的、需要不断调整的过程,不同利益相关者参与其中,除景观领域专家外,也需要庄园所有者、政府官员、企业和当地利益相关者的积极参与。适应性规划和设计是促进社会生态包容性、多样性和灵活性的有力工具。适应性规划和设计的总体目标是通过建立实验室(实践社区)来提高庄园景观的韧性和适应能力,在这些社区中,共同思考、设计和实施不同规模的可持续解决方案是核心。而为实现这一总体目标,相关的研究和设计以及重要利益相关者的参与和可视化的沟通是必不可少的(图9)[16]。

9 业主、业界专家和政府代表在研讨会上共同思考Estate owners, experts and government representatives think together in a workshop

韧性被定义为系统在不改变其主要状态的情况下对外界变化或干扰作出反应的能力[17]。适应是指在实践过程或生态系统结构中对预测或实际的气候变化可进行调整的程度。适应可以是自发的,也可以是规划的;可以是对反应的变化,也可以是对预测的变化所做的反应[18]。我们需要正确理解自然和生态系统如何运作,并采用前瞻性、“先发制人”的方法,来引导、协调和塑造由社会、经济和环境变化带来的庄园景观的动态变化,这种适应性规划和设计过程基于4个迭代阶段:收集信息、解读信息、预期发展、采取行动(图10)[16]。

10 增加韧性和适应能力的过程中的4个关键阶段Four essential phases in the process to increase the resiliency and adaptive capacity

我们的假设是,通过以设计为导向的多尺度和跨学科的方法,在空间结构、人、知识和治理方面建立韧性和适应能力。通过运用该方法,就可以结合部门活动来引导变革性的空间发展过程,以实现更协调的可持续成果。基于景观的区域设计被认为是发展韧性和适应能力的基本策略[19]:1)以景观的形态变化过程为基础,自然和庄园景观的“生理学”作为塑造空间变化的指导;2)创建和再生生命系统,生物多样性和多功能作为社会生态包容和水敏性庄园景观的基础;3)发展韧性和适应性空间框架,为该地区的协调发展(长期战略)建立强有力的结构,同时为当地项目(短期干预)创造条件;4)是以设计为导向的多尺度、跨学科的方法,是以认知为基础的空间设计,是一种整合市民、学者、商界人士和决策者等各界参与的实践。

韧性和适应能力的实现还需要建设适应性强的社会基础设施。一方面,在面对社会经济变化和干扰时,确保有效和公平公正的公众参与;另一方面,在规划和政策决策中,保证不同利益相关者的有效参与[20]。通过增加生物多样性、使用模块、采取即时反馈的方式,可以加强韧性能力、社会资本、慢变量、临界值和创新能力[17]。创新则可通过建立可靠的实验室(实践社区)、发展监督文化和从一定的失败中学习来实现[20]。在实验室中,以共同思考、设计和实施可持续解决方案为核心,由相关的研究和设计人员、重要利益相关者参与,通过可视化、沟通交流来促进发展。该实验室(实践社区)可以被理解为一个物理空间——实体实验室;也可以在方法论层面上被理解为一种交叉的研究设计方法。市民、学者、商界人士和决策者在一个由地理和制度界定的生活化环境中进行实验、共同创造和测试[21]。但这在实践中是如何应用的呢?

5 案例研究:3所Living实验室

目前,历史庄园面临的挑战是多方面的。我们与当地利益相关者(如庄园所有者、遗产专家、市政当局、水资源委员会和省政府)一起,确定了格尔德兰庄园景观保护和开发面临的三大挑战:气候适应、遗产旅游以及城市化带来的空间碎片化问题。如何在尊重遗产价值的同时应对这些挑战?我们认为,这些挑战不能在单一的庄园尺度上解决,而是需要一个基于景观的区域设计方法。这种假设意味着项目过程中需要区域层面的相关机构的参与,如省政府和水资源委员会。

为了能够建立一个为应对当地特定问题,由当地利益相关者参与,利用基于景观的区域设计方法产生解决方案的Living实验室,我们将3个庄园景观与主要的三大挑战联系对应起来,得出了以下3个针对3种挑战的研究设计实验室:1)气候适应——巴克斯溪(Baakse Beek)遗产庄园景观实验室;2)遗产旅游——格尔德兰世外桃源(Gelders Arcadia)遗产庄园景观实验室;3)空间碎片化——特韦洛(Twello)遗产庄园景观实验室。

在这3个实验室中,来自当地利益相关者、专家和代尔夫特理工大学的学生界定了每个地区的具体问题和发展潜力,并提出了未来发展策略。参与者们在实验室提供的协作、共建、实证平台上,使用真实案例实施解决方案。每个实验室根据自身实际情况,都有一系列利益相关者和发展动态变化,其中大多数目前仍在运行。这些实验同时也是在EU-interreg项目框架下进行的,这为进一步在欧洲范围内交流项目经验提供了机会。

在方法论层面,这3所Living实验室为如何通过设计来进行研究从而应对特定挑战提供了案例参考[22]。此外,也探索了在景观领域内,政府机构在维护、发展和改善历史乡村房屋、城堡、庄园中的角色。

5.1 气候适应:Baakse Beek遗产庄园景观实验室

这个实验室主要讨论气候适应性,特别强调庄园遗产的水资源相关问题,讨论庄园环境应对长期干旱与偶尔强降雨的处理方法。目标包括使庄园景观成为可调节的水系统的一部分,使新系统更具有气候适应性,找出地方当局可以承担的最佳角色,并从分析到提到解决方案的全过程中,使用基于景观的区域设计方法。

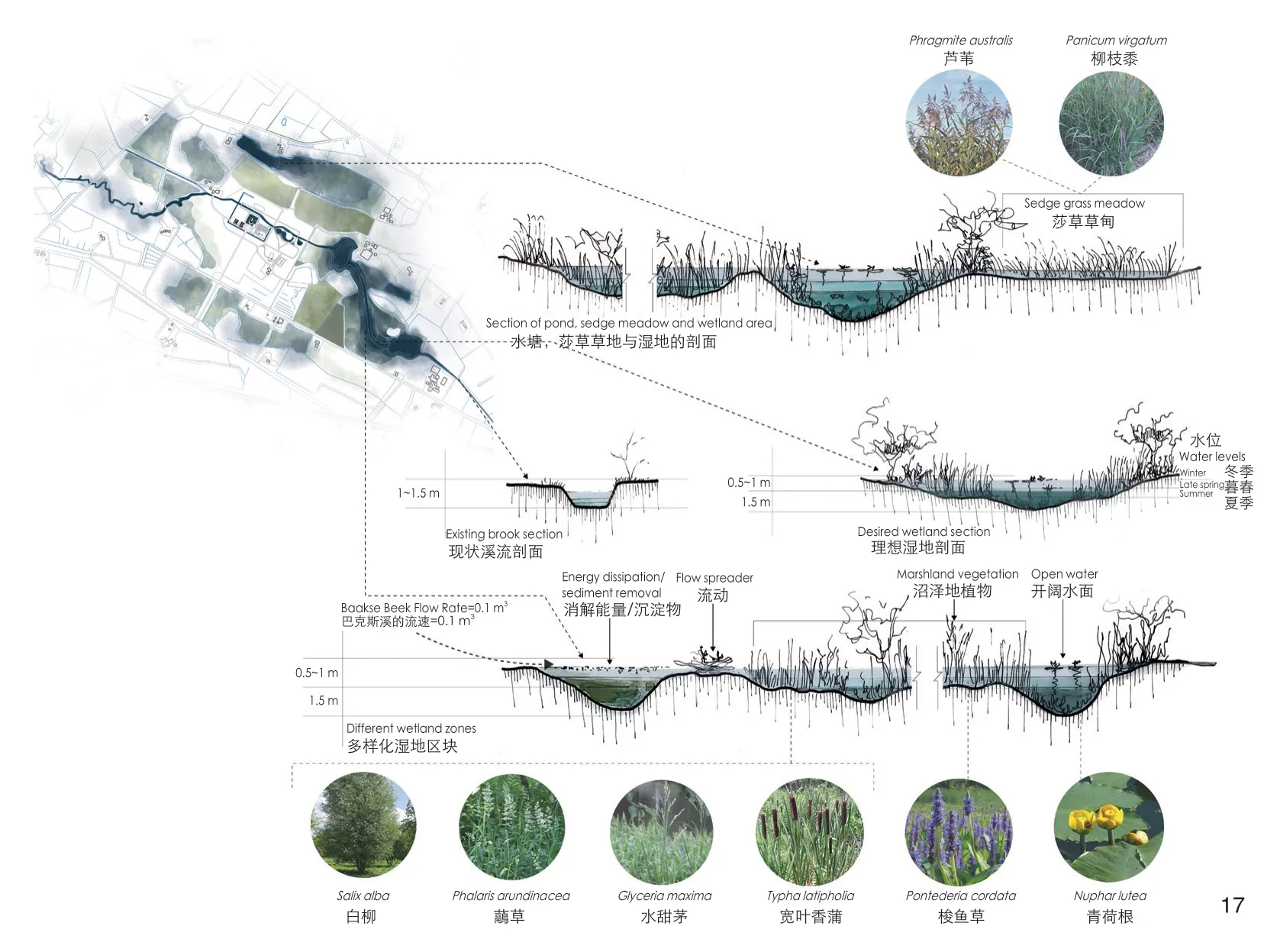

Baakse Beek地区由庄园群和农业用地组成,通过Baakse Beek溪互相联系(图11),当地大部分庄园的建设可以追溯到中世纪,其中部分庄园的所有权属于信托机构,但大多数为私人所有。大部分庄园是建筑、花园、公园和水景的综合体。近年来,气候变化导致了庄园长时间的干旱和短时间强降雨。为了解决这个问题,Living实验室研究了水资源议题对庄园遗产的重要性。地区水务局、市政当局、个人及其他业主一同合作,寻找目前应对水资源管理、自然和农业方面的挑战的解决方法。重点关注如何在庄园景观历史悠久的水资源管理结构框架下储存水资源。

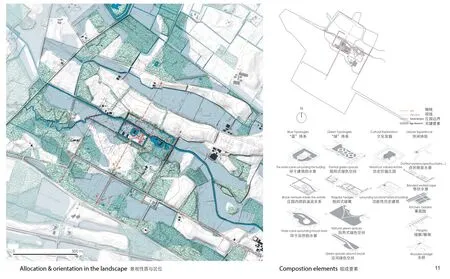

11 当地尺度上的景观分析,从分布和朝向方面分析了庄园如何与巴克斯溪的水系相关联。De wiersse位于溪谷之间,该花园的设计表达了开放的特点。视廊连接了不同的风景Landscape architecture analysis on the local scale on how the estates relate to the water system of the Baakse Beek in terms of allocation and orientation. De Wiersse is located in the brook valley, and the open character is articulated by the garden design. Vistas connect different parts of the landscape

Baakse Beek案例表明,自然、遗产、水资源管理、土地产权交换等问题可在庄园更新保护设计过程中进行探讨。空间品质是解决当今庄园景观面临挑战的首要条件,良好的空间品质也为旅游业和娱乐业提供了机会。Living实验室表明,多尺度的空间设计促成了土地所有者、水资源委员会、自然保护团体和地区当局共同努力才能实现的整体短期和长期解决方案。

这次实验室的成果包括:1)制定并实施区域水资源管理联合计划,修复历史景观结构和文化元素,在新的规划中起到缓冲和涵养水资源的作用;2)建立监测试点,监测干旱对构成庄园景观的乡村别墅和历史遗产的影响;3)确定庄园内需要通过采取施工措施解决干旱问题的区域及其具体情况。

5.2 遗产旅游:Gelders Arcadia遗产庄园景观实验室

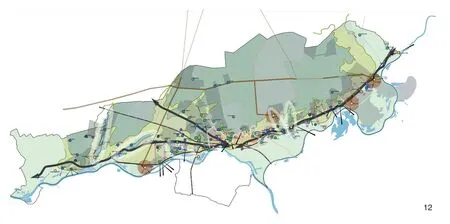

在Gelders Arcadia的庄园景观中(图12),Renkum市、Rheden市、Rozendaal市 和 瓦 赫宁根市等市政当局以及米德赫滕和格尔德兰信托基金(Middachten and the Gelderland Trust)等庄园所有者,一起在寻找发展遗产旅游和保存遗产价值之间的良好平衡。目标包括将Gelders Arcadia开发成一个连续的公共可达体验区,将城堡和乡村庄园遗产与景观和自然品质联系起来。通过“权力与荣耀”的省级旅游主题,讲述Gelders Arcadia的故事来拓宽和深化遗产旅游事业,这其中便含有权利景观与“二战”的故事。然而,发展一种现实的组织模式是基于主要利益相关者、市政当局、遗产所有者和企业家之间的合作。

12 Gelders Arcadia庄园景观空间发展的区域愿景Regional vision for the spatial development of the estate landscape of Gelders Arcadia

该地区以含沙冰脊(由冰的隆起而推动的山脊,荷兰语:Veluwezoom)为特色,自中世纪以来深受荷兰精英的喜爱。在这里遍布中世纪的城堡和庄园、18世纪摄政时期的乡村庄园以及19世纪和20世纪的现代乡村住宅,共有超过100个国家和当地庄园。此外,这里还可以找到重要的景观遗产,比如荷兰第一批景观花园之一——Biljoen市附近的Beekhuizen庄园。

此处庄园景观的独特之处是由省长和他们的贵族朋友所创造的景观结构,比如“国王之路”。国王威廉三世在他的狩猎场威卢威修建了多条连接各种狩猎小屋和城堡的道路。这类“权力景观”的维护和旅游推广是相当复杂的,因为“国王之路”目前属于不同的个人和机构,且分布在好几个行政区范围内。要实现共同的愿景并对它们进行管理具有相当大的挑战性。而且,很少有游客知道这些权力景观的历史,这些特征并不总是很容易被识别的。维持及合作非常困难,因为很多合作关系是通过临时项目建立的,通常情况下,在项目终止的时候合作关系也随之终止了。有5个市政当局尝试发挥带头作用,但这并不是一项容易的任务。庄园景观对区域经济效益具有积极促进作用,可以加强区域遗产旅游事业的发展。遗产旅游也可以成为庄园业主的宝贵收入来源,从而在一定程度上确保遗产维护工作的开展。因此,整合不同地方政府,在区域层面上实现旅游愿景是十分必要的。

从Gelder Arcadia的案例中我们了解到,由庄园所有者和当局政府共同参与的区域合作伙伴关系,可以有效地交流知识和经验。此外,企业(博物馆、酒店、餐厅等)也对区域性方法感兴趣并愿意参与其中。然而同时,没有人想带头发展区域旅游,因此区域政府的作用是至关重要的,它们是启动、刺激和促进区域发展的关键。针对上述情况,该项目采取了以下措施:通过建立一个基金会或信托基金,确保Gelder Arcadia地区合作的连续性;建立联合旅游,让当地乡村住宅的业主参与到Gelder Arcadia的“权力景观”中来;为“国王之路”制定联合管理计划,以明确潜在的挑战、机遇、解决方案和合作。

5.3 空间碎片化:Twello遗产庄园景观实验室

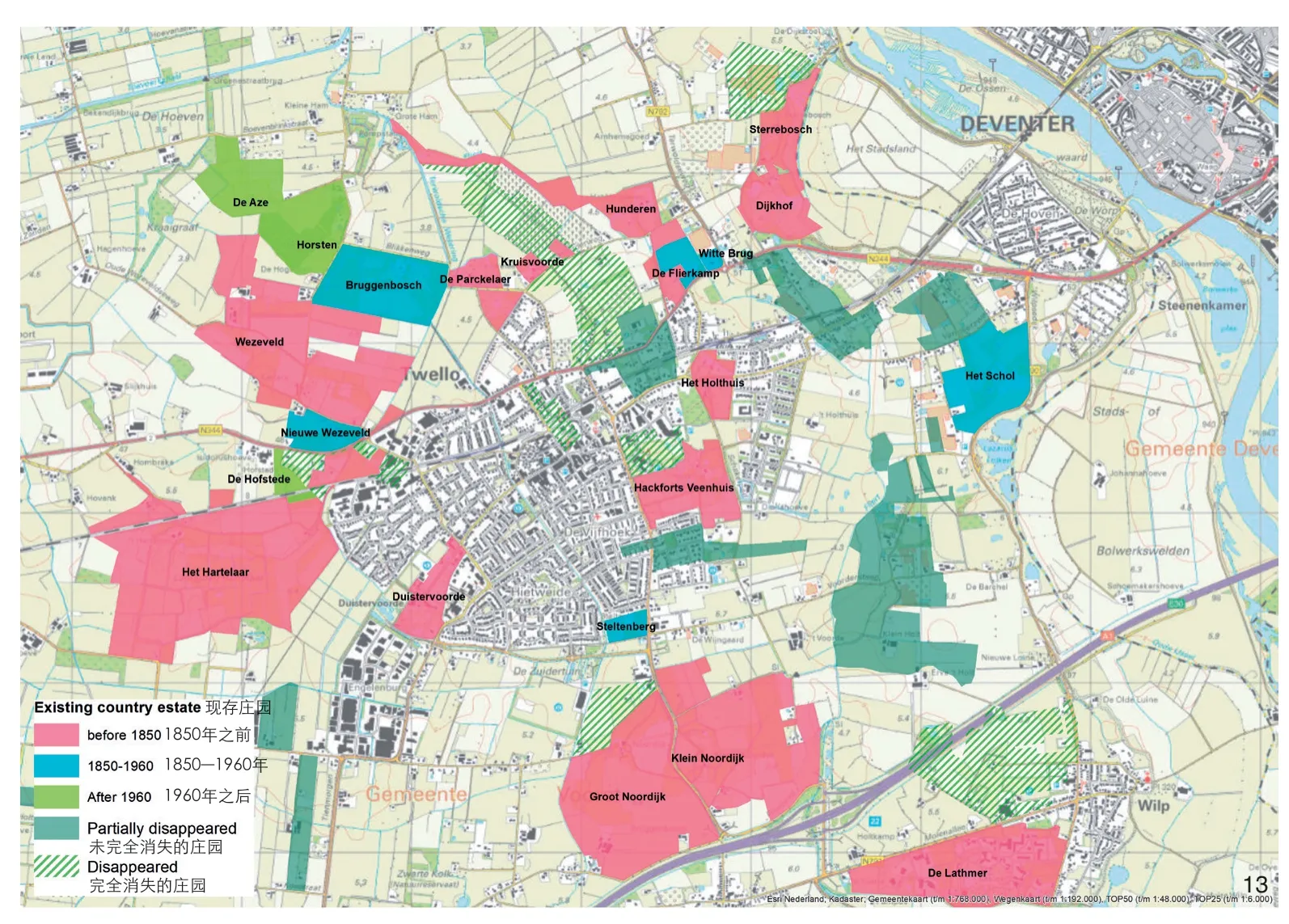

该庄园景观位于Apeldoorn市– Zutfen市– Deventer市城市三角群(图13),基础设施建设和城市扩张导致了空间碎片化问题。在这里,区域官方部门、市政府和Twello庄园周围的业主致力于加强庄园区域的空间融合,目标是保持庄园景观作为一个整体以应对空间碎片化增加和空间品质降低的风险。Living实验室的建立是为了帮助市政府创建新的保护与发展的地方立法,促进不同的业主和政府之间合作,并制定一个庄园景观联合管理计划。

13 特韦洛庄园景观开发分析Analysis of the development of the estate landscape Twello

Twello区域被描述为“城市三角群的绿心”,由Apeldoorn、Deventer和Zutphen三个城市包围。从Veluwe到IJssel山谷的高砂地质景观过渡区中涵盖各种各样的景观。人们很早就发现了该地区的美丽。18—19世纪,居住在周边城市的富裕家庭购买此处的土地来建造乡村别墅和乡村庄园。Twello拥有广阔的庄园景观(也称为Green Carré)——在公园般的景观中布满了宏伟的建筑。其丰富的文化历史是该地域特征的重要组成部分,人们希望保留并在可能的情况下加强这一特征。然而,在这片庄园景观上,正在大规模修建道路和房屋,庄园遗产正在被城市化进程所威胁。

此时此刻,我们需要一个共同的目标和计划,并确保一个活跃且有行动力的工作团体保证目标与计划的执行。因此,区域官方部门已制定新法例,以加强该地区的特色,并将庄园景观视为优质地带。在所有的新发展目标中,空间质量和文化价值应处于主导地位。这需要人们能够系统综合地看待和理解这些景观集合,而不是只关注个别的具有纪念意义的建筑。因此,创建社区意识和促进公众参与至关重要:创建人们对该地区历史和未来(潜在机会)的认识。同时,将不同利益相关方团结在一起也是至关重要的,这可以作为开发该地区的一个基础和起点。然而,除了空间品质,其他方面也至关重要。例如,讨论遗产所能带来的经济价值可以引起人们对遗产的兴趣,从而可以在项目发展过程中尝试纳入他们。此外,在维护方面的协作成本会更低。

Twello这个案例向我们展示了当区域官方部门、庄园所有者和Voorst市政府密切合作时,开发了新的空间政策工具“庄园生态圈”以保护和发展庄园景观的遗产品质。在这个案例中,“庄园生态圈”的概念得到了进一步的探索。“庄园生态圈”有助于界定现有村庄和庄园以及它们之间的连接区域,加强庄园景观(通常是以前的庄园土地)以及具有“影响范围”的区域。“庄园生态圈”确定了乡村别墅的选址和朝向,以及景观组成元素,如小巷和远景。这些信息对于市政府保护庄园景观和单个庄园现有的品质至关重要,并有助于为政府在调查决策新的开发机会时提供参考。

本次Living实验室的重要成果包括:1)地方当局和市政当局评估和开发新的空间政策工具“庄园生态圈”;2)与Twello庄园景观的当地利益相关者一起完成协作后,将Twello庄园生态圈嵌入到区域遗产保护和发展政策中;3)省政府将通过进一步的适用性(设计)研究,并与市政当局和其他遗产景观的利益相关者讨论这一概念,探索在该地区的其他遗产景观中实施这一政策工具的可能性。

6 空间设计的作用

在这3个Living实验室中,设计扮演着重要的角色,其以综合的空间设计来应对上述挑战的复杂性。庄园景观的保护和发展所面临的挑战对地方和区域范围有所影响,因此建立一个针对这些尺度和广泛利益相关者的设计过程,被证明将有助于制定设计任务书以及确定潜在空间的效果[23]。我们在Living实验室中采用了结构操作框架,在确保整体研究有序进展的同时,也为正式的设计过程留有发展空间。共同创作的各阶段设计活动由庄园所有者、区域和当地政府、风景园林师、专家、学生和其他参与者共同完成。因此,Living实验室就像一个设计工作坊,由一系列的公共会议或研讨会组成。这些会议或研讨会强调了设计的运用,以及在一个更宽泛、更持久的探索、解决和实施方案的过程中融入设计。此外,风景园林学生的加入是有价值的,因为他们提供了新鲜而公正的视角,并激发了其他参与者的创造力和想象力。在常规的官方组织框架之外,在项目中创造这种非正式交流和工作方式很好地适应了荷兰现有的社会和政治需求:在政策和实际层面探寻解决方案[23]。

在这种情况下,每个庄园景观的设计都为人们能够坐在一起对话、观察和建造提供了一个平台,这不仅体现在空间层面,更是在认知层面。设计通过研讨和实验不同方面的事物,以此来帮助聚焦相关的问题或发展的可能性,并且尝试探讨这些事物会在什么样的背景和情景下发生关联(构建想法、认知)[24]。设计过程可以明确用户和利益相关者在不同尺度上对未来发展的看法。

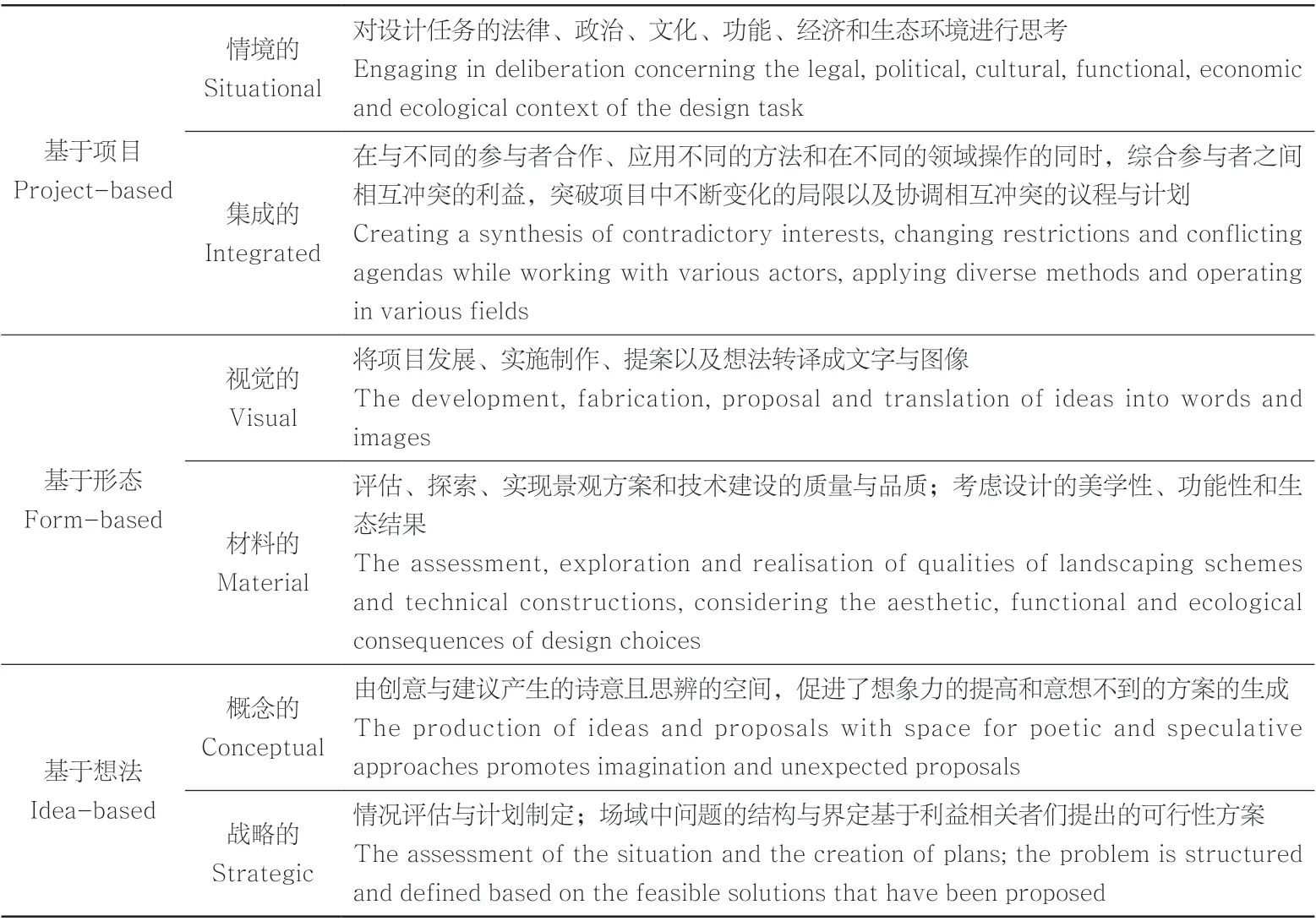

在室外空间尝试落实设计理念、功能和需求,可以让我们发现项目中的可行性、局限性以及需要进一步探索的问题[22]。在这方面,设计被用来系统地寻找空间问题的可能解决方案,目的是为设计师头脑中尚未存在的问题设想一个创新的解决方案[22],同时,也是让那些过去没有被人们发现的解决方案显现的基础。比起一个简单的过程,该设计过程是迭代的,需要经过多轮周期循环形成。一个周期基本包括3个步骤:设计想法产生、图示表达想法、验证这些被图示化的设计想法,进行更正调试后,再开始下一个循环[22]。在这个过程中,产生了3种认知类型:基于项目、基于形态和基于想法(表1)[22]。

表1 通过设计产生的认知类型Tab.1 Types of knowledge generated via design

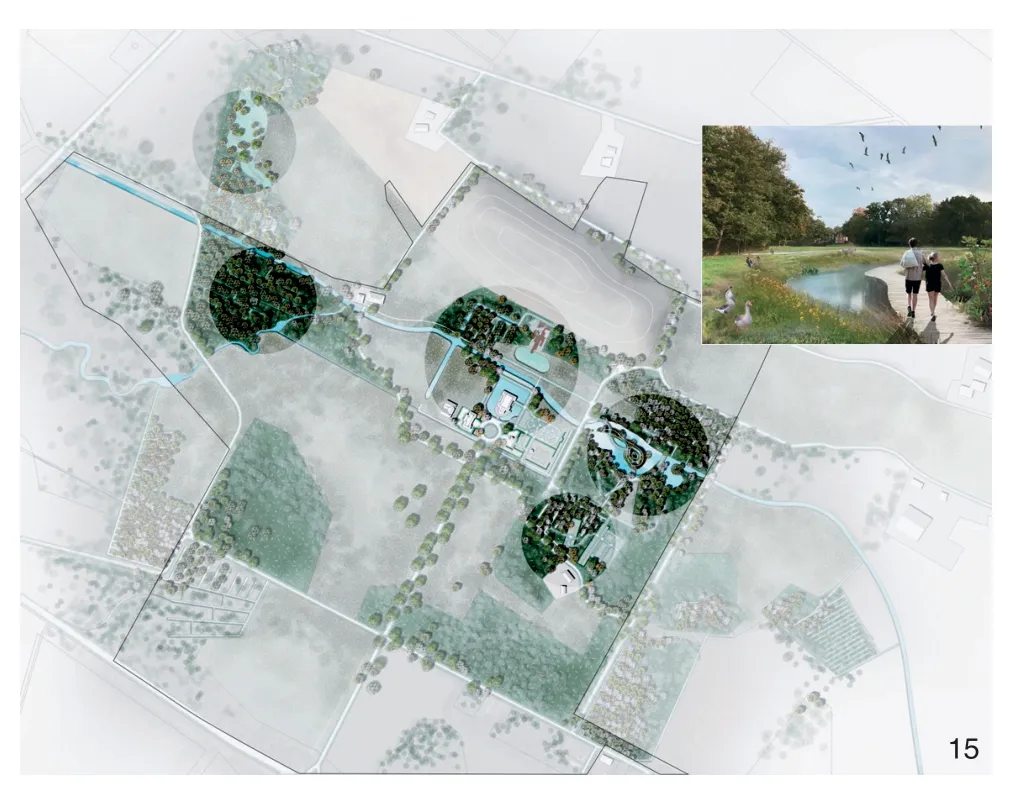

“基于项目”的相关知识主要产生于那些关注周围环境和综合解决方法的设计项目。例如,在Baakse庄园景观中,景观导向的设计方法有助于理解和创建各个庄园之间的系统性关系,通过激活历史景观要素,赋予场所新意义的同时也加强了水系统的韧性。这不仅仅促进了生态系统,也增强了人在景观中的空间体验(图14、15)。而那些看起来与计划相互冲突的利益相关者,在这个过程中则实现了为彼此助力,就像水资源管理与遗产保护那样。

14 设计探索关注于:如何将水资源管理、生态开发和游憩整合为一个景观系统,同时重新激活历史水元素,如沟林、水草甸等Design exploration on how water management, ecological development and recreation can be integrated as a landscape system while re-activating historical water elements like groove forests and water meadows

15 可视化设计显示了这个整合的空间视觉潜力(这种类型的可视化使利益相关者能够讨论法律、政治、文化、功能、经济和生态方面及其关系)Design visualisation showing spatial-visual potentials of this integration (This type of visualisations enables stakeholders to deliberate about legal, political,cultural, functional, economic and ecological aspects and their relations)

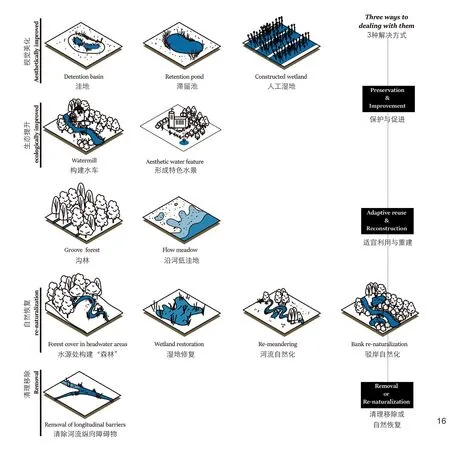

“基于形态”主要指2个方面:如何采取有效的视觉化工具进行表达与沟通,以及如何将设计具体实施建设。本研究对依托该项目所做的园林绿化方案和技术建设质量的评价、探索和实现作了进一步的探讨。例如,不同的景观设计原则是通过设计发展并测验的。设计原则可理解为一个基本的思想或规则,它控制事情如何发生或如何工作。例如:可持续水管理的设计原则、基于自然的解决方案、历史生态等。这些设计原则来源于实地研究、前人研究以及与研究遗产、水资源管理和生态专家的对话(图16)。通过设计探索和“绘制与计算”程序,可生成基于当地文脉特征的设计原则,并进一步进行测验(图17)。

16 一套庄园景观发展的设计原则Set of design principles for the development of the heritage estate landscape

17 根据“绘图和计算”程序对适用的滞流池和河岸带进行设计探索Design explorations of the applicable retention ponds and riparian zones following a ‘drawing and calculating’procedure

最后值得一提的是代尔夫特理工大学风景园林专业硕士研究生依托设计课对本研究项目进行的探讨。设计课中的研究与设计为项目提供了前瞻性的设计想法和解决方案。想法导向的知识既包含创造性、直觉性、推测性知识,也包含形成空间策略的结构性知识。在Living实验室中,认识到单个庄园是区域景观系统的一部分是至关重要的。在对单个庄园进行积极介入时,风景园林师是可以对区域层面的空间结构和演进过程做出贡献的。区域设计的探索基于所有利益相关者对情况的适当评估;场域中问题的结构与界定基于利益相关者们提出的可行性方案(图18)。

18 对生态、水管理、遗产和林业协同作用下的庄园景观的区域空间性和生态一致性的思考Speculating about the regional spatial and ecological coherence of an estate landscape in which ecology,water management, heritage and forestry synergise

通过对过程和结果的反思,我们发现如果风景园林师在政治背景下具有战略思维、行动力与想象力,他们便可以在Living实验室的各个阶段做出有价值的贡献。在历史遗产景观保护和开发的背景下,设计可以帮助人们预想和描绘一个全新的未来。设计过程则可由更广泛的市民群体与不同领域专家参与的合作机制开展。

7 总结

尽管地方当局成功地针对一些宜建、绿色的纪念碑般的建筑物设定了投资计划,但这些计划仍无法应对一些挑战,例如:水系统是一个区域层面的系统,那么针对乡村庄园中的花园和公园的干旱问题,则只能通过区域层面的方法来解决;此外,过度旅游所带来的压力是无法仅通过设计一个旅游景点式的乡村庄园来缓解的,这同样需要在区域层面上,多个乡村庄园协同来解决,比如可以通过激发、提升区域内各个庄园的特色,并打造多条连接这些有趣庄园的景观线路来实现;同样,在当下新型冠状病毒肺炎疫情的危机中,健身房等室内密闭公共空间被迫关闭,越来越多的公园和森林承载了人们日常休闲娱乐健身的需求,这同样需要一种区域性的方法来分解和承载这些需求。

因此本研究介绍了基于景观的区域设计方法。这是一种针对乡村住宅、城堡和庄园等遗产的空间组织与设计方法。它强调在景观语境下,分层并跨尺度解析遗产的历史演进过程。这种空间视角着眼探讨不同利益相关方和牵制力如何在具体物质空间上影响地区发展并塑造地区特征的同时,也被它们影响和塑造着。此外,它还探讨了更全面的进程:如何在地方、区域和省一级影响某一特定地区的发展。空间方法还可以帮助政府促进乡村住宅和庄园的保护和创新进程,从而将区域层面的目标和挑战与地方层面的目标和挑战联系起来。通过采用空间方法,我们将着眼于乡村住宅和庄园和它们所依托的其他层面空间,例如该地区的社会、经济和政治背景。

除此之外,这种方法从以保护和发展为目的的设计角度来实施,提高了庄园景观的韧性和适应能力。在这方面,基于景观的区域设计是解决气候适应性、旅游业压力和遗产景观空间碎片化的十分具有价值的工具。关键在于将庄园景观理解为一个“系统”是空间设计原则的基础,这些原则适用于单个庄园、庄园综合体、区域结构等多个尺度。设计导向的Living实验室被证明可以为业主、市政当局和其他利益相关者提供一起学习和面对当前挑战的便捷平台。同时,它还有助于建立适应性强的社会平台,以确保利益相关方在规划和决策过程中的有效参与。在这里,地方当局、当地私人和机构(土地所有者)、学生和专家可进行区域庄园研究、设计和决策,以及在教育和艺术项目中进行合作。Living实验室的研究成果一方面支撑当地遗产政策条例修编,另一方面也为面向未来的庄园遗产景观的保护与更新建立法规和提供资金补助。

该方法也适用于其他文化遗产景观,如圩田景观、不能以纪念碑方式保护的考古景观、历史村落及其周边环境等。这些珍贵的文化遗产景观必须得到保护。而“通过设计而保护”的方法与知识开发为其提供线索,以承认和培育地方多样性和区域一致性的方式保护和改造。格尔德兰省的案例表明,以历史景观结构等空间发展为基础,执行核心利益相关者全过程参与机制,采用通过规划保护的方法,可以成功地塑造具有适应未来和韧性的遗产景观。

致谢:

本文展示了一个由格尔德兰省资助的、在“特色和可持续遗产”(KaDEr)项目与EU-Interreg项目框架下的研究设计。我们诚挚地感谢所有利益相关者,代尔夫特理工大学学生和他们的导师,感谢他们对living实验室的宝贵意见和建议。

注释:

① 1)一处村庄或庄园属于一个地区或区域。从这个空间层面来看,可以很容易地缩小到省级和国家级,如果需要,还可以扩大到国际级;2)村庄或庄园作为更广泛的文化景观的一部分(包括邻国的庄园、村庄等);3)村庄或庄园可视为一个遗产集合(包括乡村别墅、城堡、公园、林地、农场等);4)乡村别墅或城堡是主要建筑,村庄与庄园的核心。

图表来源:

图1由Alessandro Bosio和Alamy拍摄;图2来源于《都灵地形图》,拍摄者为Carta;图3、7、10由斯特芬·奈豪斯提供;图4由爱丽兹·斯托默-斯密斯提供;图5由Leontine Lamers提供;图6由Pieter van den Berg提供;图8由斯特芬·奈豪斯和爱丽兹·斯托默-斯密斯提供;图9由格尔德兰省提供;图11由斯特芬·奈豪斯、Mich ielPoederoijen和 刘 慧 颖 提 供;图12由Gelders Genootschap和Poe MansReesink提供;图13由爱丽兹·斯托默-斯密斯、Sazya Zeefat和Elise Holtma、格尔德兰协会提供;图14、15由刘慧颖提供;图16由Yingjie Zhang提供;图17由Alia Shaded提供;图18由王颜娇提供;表1引自参考文献[22]。

(编辑/王亚莺 王一兰)

Designing Resilient Heritage Landscapes: A Landscape-based Regional Design Approach for the Preservation and Development of Historical Estate Landscapes

Authors: (NLD) Steffen Nijhuis, (NLD) Paul Thissen, (NLD) Elyze Storms-Smeets Translator: ZHANG Qingran Proofreader: CAI Jiaxiu

1 Introduction

This article contends a landscape-based regional design approach to understanding, planning,and designing cultural heritage landscapes. It elaborates a preservation-through-planning approach that takes spatial development with historical landscape structures as a basis and engages in a process with meaningful stakeholder engagement and visualisation/communication to invent spatial strategies and principles founded on co-creation and collaboration using design research and research through design as an essential means. In this article,we use the protection and development of heritage estate landscapes in the Province of Gelderland, The Netherlands, as an example.

The proposed approach, and the lessons learned from its application, provides valuable clues for the development of methods for management and protection of other cultural heritage landscapes,such as polder landscapes, historical villages and their surroundings, or archaeological landscapes that cannot be protected as a single monument.

In heritage estate landscapes, the regional landscape character is determined by several historic country estates[1]. Here historic castles,country houses and estates together with their gardens, agricultural land, forests, etc. (landed estates) are powerful agents that shaped regions,landscapes and societies across the world. Great examples of these territorial systems can be found in Germany, UK, Belgium, Italy, France, Denmark,Portugal and Spain, but also in Russia, Japan and China, we find beautiful exemplars (Fig. 1, 2)[2-4].Building estates and their landscapes were for centuries dominated by the nobility for whom land ownership was a basis for power[5]. The land was of little use without one or more country houses on it. These were “power houses” for ruling, business and leisure. The estate landscapes are the setting for court or papal residences, hunting lodges and parks, and farming. These are expressions of power that organised the territory in spatial, social, and economic ways. Thus there is a direct relationship between the country estates and the landscape.Here networks of water and roads organised the territory for control, providing resources and good connections to urban centres. Transport networks over land and water allowed the nobility to travel easily between the city and their country estates.

In the Netherlands, there also quite a few estate landscapes located in different parts of the country (Fig. 3). Examples can be found around the cities of Amsterdam and The Hague, but also in the North and East of the country. Here, however,country houses and landed estates are much smaller than most European counterparts. Whereas, for instance, in the UK, estates are regarded as over 1,200 hectares. In the Netherlands, most country estates are between 5 and 200 hectares, with some great landed estates of over 1,000 hectares as exceptions. Despite the modest estate sizes, there is a tremendous regional impact as country houses and estates are often located close together and makeup estate landscapes. Here the identity of the landscape is directly related to the castles, country houses and estates. Inhabitants and visitors highly appreciate these landscapes.

Regarding country houses and estates,the Dutch National Heritage Agency has listed monuments, such as country houses, coach houses,estate farms, tea pavilions, garden ornaments, parks and (parts of) country estates. There are 552 listed country estates in the Netherlands, called complex or ensemble of nationally listed country estates.

The province of Gelderland lies in the east of the centre of the Netherlands. In terms of area(5,137 km2), it is the largest of the twelve provinces of the Netherlands. Gelderland’s 51 municipalities are home to 2 million inhabitants. The region has a varied landscape with forests, large rivers and rural areas. Urban hubs like Arnhem, Nijmegen and Wageningen with international secondary schools and universities support the knowledgebased economy. In Gelderland, over 500 country houses and landed estates exist (Fig. 4). The province of Gelderland has 119 nationally listed country estates or more than a fifth of the national total. Furthermore, for 97 castles and country houses, solely the main building is listed as national monuments.

The area has been popular amongst the landed elite since the late Middle Ages. Particularly around the provincial capital of Arnhem (called Gelders Arcadia), along the river IJssel and in the easternmost part of the province, known as Graafschap (county). The undulating landscape,the rivers and brooks, and the fertile lands proved to be ideal for making the agricultural lands and aesthetic parks. Castles, country houses and landed estates still adorn the province, of which twothirds are currently still privately owned (Fig. 5).Others are owned by trusts (such as the Gelderland Trust), state organisations and governments, and commercial businesses.

These estate landscapes represent: 1) They constitute high heritage values, including monumental buildings, gardens and other landscape elements; 2)Valuable nature is concentrated in these landscapes.Nature and cultural landscapes retained their identity,much more than in other landscapes; 3) The estate landscapes offer plentiful opportunities for tourism,recreation and sport; 4) The concentrations of historic castles, country houses and landed estates are of high economic value.

In terms of conservation and protection of estates, there is a long tradition in the Netherlands,but since the 1930s, people have turned away from the estate landscapes in their entirety[1]. The focus is on the building as a monument and not on the building in the landscape context. For sustainable conservation and development of castles, country houses, and estates, it is crucial to understand them in their landscape context. This is to relate individual country houses to their immediate surroundings — garden, park, grounds — and on a regional scale, where ensembles of several country houses are considered in their surroundings. In historic estate landscapes, the buildings and other functions are interwoven with the landscape, as it were. They are part of the whole from which they derive their picturesque effect, which they in turn partly give back to the whole[1].

Climate change has a significant effect on the water management of estate landscapes, especially the abundance and shortage of water, and causes changes in vegetation due to temperature increases.At the same time, the pressure is increasing due to ongoing urbanisation and related recreational needs. Also, rural landscapes have to deal with spatial fragmentation due to urbanisation, changing ownership, change of function, etc. The complexity of these challenges needs a regional perspective or “helicopter view” to understand the coherence and systemic relationships between the estates and find common ground in which stakeholders can work together. In such an approach, knowledge of the landscape structure and coherence are linked to development opportunities of country houses through design research and design thinking across scales. Nevertheless, how can we understand estate landscapes from a spatial point of view?Furthermore, how can we apply this knowledge in protecting and future-proofing them?

2 Estate Landscapes as Cultural Landscape

Estate landscapes were not only expressions of investment, enjoyment, or power; they are also genuinely cultural landscapes. A standard definition of cultural landscape is adopted by the Council of Europe: “an area, as perceived by people, whose character is the result of the action and interaction of natural and/or human factors.”[6]This definition emphasises two aspects: landscape as the result of interaction humans with their environment and the dynamic nature of the landscape.

Landscape changes with and without human intervention. Sometimes the changes are farreaching, sometimes less so. Some changes, such as the consequences of climate change, take a long time to become visible. Nevertheless, change can also occur swiftly, as when a new housing development is built in a former agricultural area.This is why landscape can be conceived as a living system, which is to say, a complex and dynamic network of subsystems that are constantly changing in response to natural processes, social demands and technical possibilities. In this perspective, we should understand estate landscapes as an interface between nature and society, which manifests itself in a material space of both structures and processes.

A practical and widely used method entails analysing the landscape in layers and organising them according to the influence and dynamics of change[7].Unpacking the estate landscape in layers is a way of grasping the different systems and subsystems and their relationships. This dissection into layers should not be seen as a static or hierarchical arrangement. Instead, it is about discrete layers that influence one another to a greater or lesser degree,and that influence may also change with time. Here the relation between the layers of the physical environment (hardware), human activity (software),and cultural, institutional and conceptual ideas(orgware) is regarded as essential to understanding the estate landscape and its genesis[8](Fig. 6).

2.1 Natural Context

The natural context is relief, water, soil,geological substructure and climate, and the connected ecosystems. The natural context should not be regarded as a discrete factor but as a central and inextricable component of the system that determines how the landscape can be used. The dynamics of this primary condition are characterised by a slow, often almost imperceptible,process of change, repetition and natural cycles.

2.2 Human Modifications and Interventions

Human activity is part and parcel of using the natural context for living, working and recreation.Human beings appropriate the natural environment through agriculture, building country estates and their gardens, road building, canalisation of watercourses, etc. Throughout history, that appropriation process has led to a succession of sometimes drastic changes in the landscape.

2.3 Culture, Organisation and Politics

This layer comprises the cultural, spiritual and religious conceptions of the natural context and our engagement with it, including the state of science and technology, organisational forms,political movements, design concepts and aesthetic ideals. Water, for example, has different meanings in different cultures, which can find expression in landscape architectural treatments in parks and gardens. The dynamics of this layer relate to the relatively short term, linked to people and politics.

An understanding of estate landscapes is inherent to the concept of the layers and their relationships that constitute the landscape system(Fig. 7). The estate landscape is a relational structure that connects and influences scales and spatial,ecological, functional and social entities. The estate landscape is a holistic system and a scale continuum that we can only understand by looking at different spatial scales and their relationships. That is to say that individual country houses, together with their gardens, parks and grounds, make up an estate, and that multiple estates make up an estate landscape,and the estate landscapes make up a region (Fig. 8)①.Thus country estates are part of a scale-continuum in which relationships are shaped via the attachment,connection, and embedment of a specific site or location into the broader context at different scale levels.

3 Estate Landscapes as History

Time is an essential factor in understanding estate landscapes. Over time estates landscape underwent transformations resulting from selections based on possibilities and evaluation.Some structures, patterns, and forms were preserved; others continue to develop or are replaced by new ones, resulting in a rich historical and typological variation[8]. Spatial transformation or series of transformations usually balance more permanent landscape structures and others more prone to rapid change[9]. The more permanent ones tend to be resistant to change and, over time,become more robust (and even inert). Those asynchronous transformations turn the landscape into a layered whole in which physical traces of time can reinforce or contradict one another[10].

Broadly three critical phases of estate building can be identified in Gelderland: 1) Middle Ages—1600: castles with large landed estates for nobility (landed elite); 2) 1600—1800: country houses and estates for city regents; 3) 1800—1940:smaller country houses for elite borne of finance,commerce and industry.

These phases provide a window on a range of chronologies, events and meanings that connect the traditional and the contemporary, the tangible and the intangible. In that respect, an estate landscape is so rich in meaning that it can be “read” as a biography, as a palimpsest that illustrates the key activities that have contributed to the formation of that landscape[11-12].

Key to the estate landscape as history is the notion of the Longue durée, the landscape as a long-term structure that changes over time in the process of “sequent occupance”[13-14]. A knowledge of these historical traces is one of the starting points for new transformations of the estate landscape: the addition of new “layers”. The evolution of the estate landscape is inherent in the“erasure” and the “writing” of history. As we see it now, the estate landscape results from a gradual process of selection in which some elements remain, and others change or are replaced.

Time is an essential factor in understanding estate landscapes. Over time estates landscape underwent transformations resulting from selections based on possibilities and evaluation.Some structures, patterns, and forms were preserved; others continue to develop or are replaced by new ones, resulting in a rich historical and typological variation. Spatial transformation or series of transformations usually balance more permanent landscape structures and others more prone to rapid change. The more permanent ones tend to be resistant to change and, over time,become more robust (and even inert). Those asynchronous transformations turn the landscape into a layered whole in which physical traces of time can reinforce or contradict one another.

4 Towards Resilient Heritage Estate Landscapes

Climate change, increasing tourism demands,etc., calls for a careful approach because rapid spatial development and functional change can compromise the layering and legibility of the estate landscape. There is a danger that the cultural identity will disappear. To avoid this requires a “management of change” approach to create a future-proof estate landscape in which the past, in one form or another, continues to play an appropriate role[15].This demands a dynamic and political process that is not confined to the domain of the landscape experts but in which estate owners, government officials, business, local stakeholders are also actively involved. Adaptive planning and design is a powerful vehicle to foster socio-ecological inclusivity, diversity and flexibility. The overall aim of adaptive planning and design is to increase the resiliency and adaptive capacity of heritage estate landscapes by establishing communities of practice, where thinking together and generation and implementation of sustainable solutions at different scale levels are central and is facilitated by research and design, meaningful stakeholder involvement and visualisation/communication (Fig. 9)[16].

Resilience is defined as the capacity of a system to respond to change or disturbance without changing its primary state[17]. Adaptation is the degree to which adjustments are possible in practices, processes, or structures of systems to projected or actual climate changes. Adaptation can be spontaneous or planned and can be carried out in response to or anticipating changes in conditions[18]. This implies a proper understanding of how natural and systems function and a forward-looking, pro-active approach that guides,harmonises, and shapes changes and dynamics in the estate landscape, which are brought about by social, economic, and environmental processes.Such an adaptive planning and design process is based on four iterative phases: collecting information, gaining understanding, plan development, and action perspective (Fig. 10)[16].

The assumption is that through a designoriented multi-scale and transdisciplinary approach,resiliency and adaptive capacity can be built up in terms of the development of spatial structures and people, business, knowledge, and governance.Doing so can steer transformative spatial processes through a combination of sector activities aimed towards more coordinated sustainable outcomes.Landscape-based regional design is considered to be an essential strategy for developing resiliency and adaptive capacity by[19]: 1) Taking the landscape form and process as fundament; physiology of the natural and estate landscape as a guide to shaping spatial transformations; 2) Creating and regenerating living systems; (bio)diversity and multi-functionality as the basis for socio-ecological inclusive and water sensitive estate landscapes;3) Developing of resilient and adaptive spatial frameworks; strong structures for the coherent development of the region (long-term strategy)while setting conditions for local projects (short term intervention); 4) A design-oriented multiscale and transdisciplinary approach: knowledgebased spatial design as integrating practice,involving people, academia, business, professionals,government officials.

Resiliency and adaptive capacity also require building an adaptable social infrastructure to assure meaningful participation and achieve equity in the face of socio-economic change and disturbance and meaningful participation by stakeholders in planning and policy decisions[20]. Biodiversity,modularity, and tight feedback can strengthen resilience capacity, social capital, slow variables and thresholds, and innovation[17]. Resilience capacity is well-suited to an adaptive approach to planning and design. Innovation is pursued through responsible experimentation, developing a culture of monitoring,and learning from modest failures[20]. This can be achieved by setting up a living laboratory where thinking together, generation and implementation of sustainable solutions are central and is facilitated by research and design, meaningful stakeholder involvement and visualisation/communication. The living lab or community of practice can be considered both physical location and joint approach. Citizens,academia, business and policymakers experiment,co-create, and test in a life-like environment, defined by geographical and institutional boundaries[21]. But how does this work in practice?

5 Three Living Labs as Learning Cases

The present-day challenges that face historic estates are manifold. Together with local stakeholders, such as estate owners, heritage experts, municipalities, water boards, and the Provincial Authority, we identified three significant present-day challenges for protecting and developing the estate landscapes in Gelderland:climate adaptation, heritage tourism, and spatial fragmentation due to urbanisation. How can these challenges be met with respect for the heritage values? We presume that these challenges cannot be solved on a single estate but require a landscapebased regional approach. This presumption implies a role for (governmental) organisations that work on the regional scale, such as the provincial government and the water boards.

In order to be able to set up a living lab that can involve local stakeholders, address specific issues,and generate solutions utilising the landscape-based regional design approach, we connected the main challenges to three particular estate landscapes. This resulted in the setup of the following three living labs: 1) Climate adaptation: heritage estate landscape Baakse Beek; 2) Heritage tourism: heritage estate landscape Gelders Arcadia; 3) Spatial fragmentation:heritage estate landscape Twello.

In these three living labs, local stakeholders,experts, and students from TU Delft identified each region’s specific problems and potentials and generated ideas for future development. Each living lab provided a platform to collaborate,co-create and experiment while using real cases and implementing solutions. Each of these labs has its own set of stakeholders and its dynamic,and most of them are still running. The labs are also connected to the EU-Interreg project Innocastle which gave the opportunity to exchange experiences in a European context.

The three living labs are learning cases that shed light on how to deal with specific challenges and enabled us to explore the power of research through design[22]. Moreover, to discuss and improve government agencies’ role in maintaining,developing, and improving historic country houses,castles, and landed estates in a landscape context.

5.1 Climate Adaptation in the Heritage Estate Landscape of the Baakse Beek Area

This living lab addresses the significance of the estate heritage for water issues, particularly climate adaptation: dealing with long periods of drought and occasionally heavy rain in the estate environment.Objectives include: making heritage part of changing the water system towards climate adaptivity, finding out what role the regional authority can play best,and introducing landscape design as a contribution to move from analysis to solutions.

The Baakse Beek area consists of landed estates and agricultural land, interconnected by the Baakse Beek, a brook (small river, Fig. 11).The majority of the estates date back to Medieval times. Trust organisations own some, but most of them are privately owned. Most of the estates are A-listed as ensembles of buildings, gardens, parks and water features. In recent years, climate changes have led to long periods of drought and short intervals of intense rainfall. In order to address this issue, the living lab looked at the significance of the estate heritage for water issues. The regional water authority and the municipality, and private and other owners collaborate to find solutions for present-day challenges on water management,nature, and agriculture. The focus is on water retention within the context of historic water management structures in the estate landscapes.

The learning case of Baakse Beek showcases that an estate landscape such as this one has many opportunities to combine and connect various themes: nature, heritage, water management,exchange of landed property. Spatial quality is a primary condition in addressing the present-day challenges at estates. There is also an opportunity for tourism and recreation. The living lab shows that the multi-scale spatial approach facilitates integral short- and long term solutions that the joint efforts of landowners can only achieve,the water board, nature conservation groups and the regional authority. The following actions are the result of this collaboration: 1) They are developing and implementing a joint regional water management plan. Historical landscape structures and cultural elements are rehabilitated and play a role in buffering and retaining water in the region.2) Setting up monitoring-pilot of the impact of drought on the heritage of country houses and historic estates that make up the estate landscape;3) Identify situations in estate zones where construction measures need to be implemented to solve problems caused by drought.

5.2 Heritage Tourism and Spatial Quality in the Estate Landscape Gelders Arcadia

In the estate landscape Gelder’s Arcadia(Fig. 12), the municipalities of Arnhem, Renkum,Rheden, Rozendaal and Wageningen and owners such as Middachten and the Gelderland Trust work on finding a good balance between strengthening heritage tourism in the estate landscape and preserving heritage values. Objectives include the development of Gelders Arcadia into a coherent publicly accessible experience zone that links the heritage of castles and rural estates to the qualities of landscape and nature. Including the broadening and deepening of heritage tourism by telling stories of Gelders Arcadia, among them power landscapes and WWII, through the provincial tourist theme“Power and Splendor”. However, the development of a realistic model of organisation based on cooperation between the main stakeholders, the municipalities, heritage owners and entrepreneurs.

Characterised by the relief of the ice-pushed ridge (Veluwezoom), the area was popular among the Dutch elite from the Middle Ages onwards.Medieval castles and landed estates, 18th-century regent country estates and modern 19th- and 20thcentury country houses can be found. In total, over one hundred country and landed estates have been identified. Also, important landscape architecture heritage can be found here, like one of the first landscape gardens in the Netherlands, Beekhuizen,near Biljoen.

Special features in this estate landscape are the landscape structures created by the stadtholders and their noble friends, such as the so-called King’s roads. Stadtholder king William III constructed long roads on the Veluwe, his hunting grounds, to connect various hunting lodges and castles. The maintenance and touristic promotion of such“power landscapes” are complex as the King’s roads are owned by various private and institutional owners and are situated in several municipalities.A joint vision and management are challenging to realise. Also, not many (heritage) tourists are aware of the history of these power landscapes. The features are not always well recognisable.

The continuity of initiatives is demanding as the partnerships arise with temporary projects but standstill at the end of a project. The five municipalities try to take the lead, but this is not an easy task. Estate landscapes have a positive effect on regional economic benefits and can strengthen regional heritage tourism. Heritage tourism can also be a valuable source of income to estate owners,thus helping to sustain these estates. A regional tourism vision is necessary.

The learning case of Gelders Arcadia showcases that a regional partnership on estate landscapes, in which both estate owners and authorities participate,can be successful in the exchange of knowledge and experiences. Entrepreneurs (museums, hotels,restaurants etc.) are interested in a regional approach and willing to participate. At the same time, no one wants to take the lead towards regional tourism.Therefore the role of the provincial government is crucial to initiate, stimulate and facilitate regional development. In order to do so, the following actions are taken: 1) Ensuring continuity in regional collaboration in Gelders Arcadia by setting up a foundation or trust; 2) Setting up a joint touristic approach to the power landscapes of Gelders Arcadia,enabling local country house owners to participate;3) Setting up a joint management plan for the King’s Road to distinguish possible challenges, opportunities,solutions and collaborations.

5.3 Spatial Fragmentation of the Country and Landed Estates in the Estate Landscape Twello

This living lab is about combatting spatial fragmentation of the estate landscape of Twello in the middle of the urban triangle Apeldoorn-Zutphen-Deventer (Fig. 13). Spatial fragmentation has occurred through infrastructural and urban expansion. Here the regional authorities, the municipality and owners around Twello worked on strengthening the spatial cohesion of the estate zone. The goal is to keep the estate landscape as a whole as there is a risk that fragmentation increases and quality disappears. This living lab is established to help the municipality create new local legislation for the protection and development,facilitate collaboration between various owners and governments, and develop a joint estate landscape management plan.

The region around Twello is described as“the green heart of the city triangle” enclosed by the cities of Apeldoorn, Deventer and Zutphen.The area offers various landscapes in the high sand transition area from the Veluwe to the IJssel Valley.The beauty of this rural area was recognised early on. In the 18thand 19thcentury wealthy families from the surrounding cities bought plots of land to build country houses and country estates.Twello has an expansive- ranging estate landscape(also called the Green Carré), full of monumental buildings in a park-like landscape. This rich cultural history is a crucial part of the region’s identity that it wants to retain and – where possible –strengthen. This estate landscape is threatened by building roads and houses.

A common goal and plan are needed and make sure to keep this alive through an active community. Therefore, new legislation is in place to reinforce the character of the area and recognise the estate landscape as a quality zone. In all new developments, the spatial quality and the cultural values should be leading. This requires knowledge of the collection rather than knowledge of the individual monuments. For this reason, it is vital to create awareness amongst the community and involvement of the public: creating awareness of the history and future of the area (the potential opportunities). It is also crucial to bring the different parties together. This can be used as a base to develop the area. However, it is vital to not only talk about quality but other interests as well. Economic arguments, for example, can convince some people who are not interested in the heritage argument. In addition, collaboration on maintenance is cheaper.

This learning case Twello showcases that where regional authorities, estate owners and the municipality of Voorst closely collaborate, new spatial policy tools can be developed to protect and develop the heritage qualities of the estate landscape. In this case, the concept of the “estate biotope” was explored further. The estate biotope helps define the existing country and landed estates and connecting areas, areas with opportunities to strengthen the estate landscape (often former estate lands), and areas with a “sphere of influence”.The estate biotope identifies essential aspects of the country houses’ location and orientation and landscape architecture composition elements such as lanes and vistas. Having this information is vital for the municipality to preserve the estate landscape and individual estates’ existing estate qualities and helps to offer insights when investigating new development opportunities.

Important outcomes of this living lab include:1) The regional authorities and municipality will evaluate and develop the new policy tool ‘estate biotope’ together with local stakeholders of the estate landscape Twello; 2) When finalised,embedment of the estate biotope Twello in the regional policy on heritage protection and development; 3) The province will explore the possibility to implement this policy instrument also in other heritage landscapes in the region through further (design) research on applicability and meetings to discuss the concept with municipalities and stakeholders in the other estate landscapes;

6 The Role of Spatial Design

In the three living labs, design plays an essential role to get a grip on the complexity of the mentioned challenges and addressing them in an integrated and spatial way. The challenges for the preservation and development of the heritage estate landscapes have impacts that cut across local to regional scales, so setting up a design process that addresses these scales and engages a wide range of relevant stakeholders proved helpful for formulating design briefs and identifying potential spatial outcomes[23]. In the living lab, a structured but informal design process was employed. Various co-creation rounds are gone through by estate owners, regional and local authorities, landscape designers, experts, students,and other participants. As such, the living lab was like a design studio that consisted of a range of public meetings or workshops that addressed the challenges of utilising design and integrates them into a more extensive and more protracted process of developing solutions and implementing them. Also, the input of landscape architecture design student was valuable as they provided fresh,unbiased perspectives and stimulated the creativity and imagination of the involved participants. The informal space created, independent of everyday hierarchies, fits in well with the social and political conditions needed to generate solution on a policy level and practical levels[23].

In this context, the design outcomes for each estate landscape provided a context for conversation, observation and construction, not only in spatial terms but also in cognitive terms.The design helps to set the problem or possibility by “naming” the things that will be attended to and frame the context in which they will be attended(framing of thoughts)[24]. The design process identifies what users and stakeholders think about future developments at different scale levels.

Positioning ideas, programs, and demands in outdoor space make it possible to discover the possibilities, limitations, and questions that call for further exploration[22]. Designing in this regard is employed as a systematic search for possible solutions to a spatial problem. This activity aims to visualise an innovative solution to a problem that does not yet exist in the designer’s mind[22]. It is also the base for the representation of solutions that were not previously visible. Rather than a straightforward process, the design is iterative and runs through various cycles of idea formation,drawing up representations and testing visualised ideas[22]. While going through this process, three types of knowledge were generated: project-based,form-based, or idea-based (Tab. 1)[22].

Project-based knowledge generated by design concerns the situation in its surroundings and the integrated solutions provided for it. In the estate landscape Baakse Beek, for instance, the landscapebased design approach helped to understand and create systemic relations amongst the individual estates in order to increase the sponge capacity of the water system while re-activating historical landscape elements, but also to boost the ecosystem and the spatial experience within the landscape(Fig. 14, 15). Seemingly conflicting agendas and stakeholders, such as water management and heritage protection, strengthened each other.

Form-based knowledge involves visual communication and the materialisation of the design (that is, how can it be created?). Here the assessment, exploration and realisation of qualities of landscaping schemes and technical constructions are explored further. For instance, different sets of landscape design principles were developed and tested through design. Design principle refers to a basic idea or rule that explains or controls how something happens or works. Examples include design principles for sustainable water management,nature-based solutions, historical ecology, etc. These design principles were derived from field study,precedent study and conversations with heritage,water and ecology experts (Fig. 16). Through design explorations and “drawing and calculating”procedures, the possibilities of the design principles are contextualised and tested (Fig. 17).

Last but not least, the design studios resulted in idea-based knowledge. Ideas-based knowledge consists of creative, intuitive, and speculative knowledge and the structured knowledge that results in a spatial strategy. In the living labs, it became vital to understand that individual country estates are part of a regional landscape system.While working on individual estates, one can contribute to regional structures and processes. The regional design explorations are based on a proper assessment of the situation by all stakeholders; the problem is structured and defined based on the feasible solutions that have been proposed (Fig. 18).

Reflecting on the process and the outcomes,the observation is that landscape architects can make valuable contributions in all phases of a living lab if they have an affinity for strategic thinking and acting in a political context, in addition to the power of imagination. In the context of historical estate landscape protection and development,design can describe prospective futures based on new forms of collaboration between stakeholders and expertise from more extensive civic and professional networks.

7 In conclusion

Though the regional authority has a successful program of investing in (built and green) monuments,some challenges cannot be met by this policy, e.g.the problem of drought that affects the gardens and parks of individual rural estates can only be solved by a regional approach since the water system is a regional one. Moreover, the challenge of durable tourism cannot be met by an individual country estate but also requires a regional approach that connects interesting places by routes through attractive landscapes. Furthermore, there is increasing use of parks and forests for recreational use in the presentday corona crisis, with lockdowns and closed gyms. A regional approach for spreading visitors is needed.

That is why a landscape-based regional design approach has been introduced. This implies a spatial approach to heritage, specifically to country houses,castles and estates, analysing historical and modern developments and processes on various spatial levels in a landscape context. A spatial view focuses upon how different actors and forces interact in particular places, shaping the character of these places yet at the same time being shaped by them. Furthermore,it explores how more comprehensive processes influence developments in a particular place at a local, regional and provincial level. A spatial approach can also help governments stimulate conservation and innovation processes of country houses and estates, thereby connecting goals and challenges on a regional level to those on a local level. By taking a spatial approach, one will look at particular places (country houses and estates) and the space in which these places exist: the social,economic and political contexts of the region.

This approach also increases the resiliency and adaptive capacity of the estate landscapes by providing a perspective on protection and development through design. In this regard,regional landscape design is a valuable tool to address climate adaptation, tourism, and spatial fragmentation of heritage estates landscapes. The key is that understanding estate landscapes as systems are the basis for identifying spatial design principles that address multiple scales ranging from individual estates, ensembles of estates to regional structures and processes. The designoriented living labs proved to be a handy platform to learn based on current challenges, together with owners, municipalities and other stakeholders. It also helped build an adaptable social infrastructure to assure meaningful participation by stakeholders in planning and policy decisions. Here regional authorities, local private and institutional landowners, students and experts have been working together in regional estate research,design and policy-making, and educational and art projects. The findings of the living labs support the regional authority in renewing their heritage policy program and provide regulations and subsidies to contribute to the protection and development of future-proof heritage estate landscapes.

The presented approach is also applicable to other cultural heritage landscapes such as polder landscapes, archaeological landscapes that cannot be protected as monuments, historical villages and their surroundings etc. These valuable cultural heritage landscapes must be safeguarded too. The discussed planning preservation-through-planning approach and knowledge development can provide clues for preserving and transforming them in ways which acknowledge and cultivate their local variation and regional coherence. The cases from Gelderland illustrate that a preservation-throughplanning approach that takes spatial development with historical landscape structures as a basis and engages in a process with meaningful stakeholder engagement can successfully lead to future-proof and resilient heritage landscapes.

Acknowledgments:

This article reflects a research and design project that the Province of Gelderland funds (The Netherlands) in the framework of the “Characteristic and Sustainable Heritage(KaDEr)”-program and the EU-Interreg project Innocastle.We like to thank all involved stakeholders, TU Delft students and their mentors for their valuable input to the living labs.

Notes:

① 1) A region or regional zone to which the country/ landed estate belongs. From this spatial level, one can easily zoom out to provincial and national level, and if needed, the international level; 2) The country or landed estate as a part of a broader cultural landscape (including neighbouring country and landed estates, villages, etc.); 3) The country or landed estate as a heritage ensemble (including a country house or castle, parklands, woodlands, farms, etc.); 4) The country house or castle is the main building, the core of the country or landed estate.

Sources of Figures and Table:

Fig. 1 © Alessandro Bosio /Alamy stock photo ; Fig. 2 ©Carta topografica di Torino e dei dintorni;Fig. 3, 7, 10 ©Steffen Nijhuis; Fig. 4 © Elyze Storms-Smeets; Fig. 5 ©Leontine Lamers; Fig. 6 © Pieter van den Berg; Fig. 8 ©Steffen Nijhuis & Elyze Storms; Fig. 9 © Province of Gelderland; Fig. 11 © Steffen Nijhuis, Michiel Pouderoijen& Huiying Liu; Fig. 12 © Gelders Genootschap & Poelmans Reesink; Fig. 13 © Elyze Storms-Smeets, Sazya Zeefat &Elise Holtman; Fig. 14, 15 © yinghui Liu; Fig. 16 © Yingjie Zhang; Fig. 17 © Alia Shaded; Fig. 18 © Yanjiao Wang;Tab. 1 © reference [22].

(Editor / WANG Yaying, WANG Yilan)