Understanding South African mothers’ challenges to adhere to exclusive breastfeeding at the workplace:A qualitative study

Nompumelelo Maponya,Zelda Janse van Rensburg ,Alida Du Plessis-Faurie

Department of Nursing,University of Johannesburg,Johannesburg,South Africa

Keywords:Breast feeding Qualitative research South Africa Workplace

ABSTRACT Objective: This study aimed to gain an in-depth understanding of the experience of South African working mothers in the adherence to exclusive breastfeeding when returning from maternity leave.Methods: The data of the study was collected using face-to-face semi-structured interviews.Eight breastfeeding mothers were purposefully selected from two primary health care clinics in Rustenburg,North West Province,South Africa.The data were coded,categorized,and clustered into themes using Giorgi’s phenomenological analysis.Ethical considerations and measures of trustworthiness were adhered to throughout the study.Results: The findings revealed three themes:a desire for working mothers to continue the adherence to exclusive breastfeeding,workplace support for breastfeeding mothers in the adherence to exclusive breastfeeding,and an unsuitable workplace environment for the adherence to exclusive breastfeeding.Six sub-themes were identified:the need to return to the workplace soon after baby’s birth,psychological responses in the adherence to exclusive breastfeeding,lack of support from employers and coworkers in the adherence to exclusive breastfeeding,lack of or partial implementation of breastfeeding policies in the workplace,the workplace not being supportive for mothers’having to express and the workplace not being supportive for mothers’ having to store breastmilk.Conclusion: Based on the findings,South African government should revisit employment policies to support working mothers who need to continue with exclusive breastfeeding after returning from maternity leave.

What is known?

• The benefits of breastfeeding for both mother and baby are well established.

• The WHO recommends exclusive breastfeeding for six months without introducing any other commercial breast milk substitutes,liquids,or solid foods.

• In South Africa,a developing country with a high prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus(HIV),breastfeeding is essential for the growth and development of babies and the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV.

• The South African Basic Conditions of Employment Act of 1997,declares that a pregnant employee is entitled to four consecutive months of maternity leave.Still,companies are not under a legal obligation to remunerate employees during maternity leave.

• The Government Gazette’s Code of Good Practice on the protection of employees during pregnancy and after the birth of a child elaborate in detail how a breastfeeding employee should not be allowed to perform hazardous work to her or her child.The document does not refer to conditions to support the breastfeeding woman to adhere to exclusive breastfeeding at the workplace.

What is new?

• This article highlights the experiences of South African working mothers in adherence to exclusive breastfeeding after returning from maternity leave.Although many workplaces in South Africa have adopted a breastfeeding friendly policy,many still only have this partially implemented or not at all.Even though the WHO guides exclusive breastfeeding for six months,the implementation of breastfeeding policies in the South African workplaces is lacking.The South African Labor Relations Act and Basic Conditions of Employment Act do not provide any supportive measures to support mothers to continue providing their babies with breastmilk for six months after birth,as recommended by the WHO.Therefore,South African working mothers are left being vulnerable,and the well-being of both mother and baby are compromised.

1.Introduction

In 2016,the recorded number of live births in South Africa was 969,415[1],of which 783,322(80.8%)were to mothers between the ages of 20-39 years,which are considered the ‘working class’ age group [1].Women form many labor markets,including domestic workers,retail,hospitality,education,and nursing.Many of these working women are in the childbearing ages[2].The population of female employees in their childbearing age is growing [3].The benefits of breastfeeding for the well-being of both mother and baby have long yet been established.The workplace remains a deterrent to the adherence to exclusive breastfeeding [3].Women who breastfeed have a lower risk of developing postpartum depression,type 2 diabetes,rheumatoid arthritis,breast and ovarian cancers than those who did not breastfeed[4,5].Adherence to exclusive breastfeeding decreases babies’illness and death rates but allowing breastfeeding breaks at the workplace also increases work productivity and holds long-term financial benefits for the employer [6].These economic benefits are,however,not captured in revenue flows [4].Despite the advantages mentioned above,working mothers who work away from home often have no choice but to discontinue breastfeeding when returning to the workplace after maternity leave[7].Full-time employment is one of the major reasons for the discontinuation of breastfeeding.Often,breastfeeding is not even initiated due to having to return to employment soon after the baby’s birth [4].

Under the South African law,breastfeeding employees are protected by the Basic Conditions of Employment Act (BCEA) of 1997[8].The BCEA indicates the prescribed maternity leave in South Africa as four months.The payment of maternity benefits is,however,governed by the South African Minister of Labor,subject to the provision of the Unemployment Insurance Act(Act 63 of 2001)[9]on the condition that the employee is registered at the Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF) by her employer.In many South African government sectors and large private companies,the four months of maternity benefits are usually unpaid[10].This leads to South African working mothers having to return to work before their baby is six months old,despite the WHO recommending mothers exclusively breastfeed their babies for six months.The BCEA’s [9] Code of Good Practice (COGP) (S5.13) endorse that workplaces must make arrangements for pregnant and nursing employees to have 30-min breaks twice a day to breastfeed or express breast milk for the first six months after the baby’s birth[2].But specific breastfeeding friendly South African workplace policies do not exist,therefore not stipulating whether or not to keep the baby at the workplace for breastfeeding time or a suitable area to express breastmilk and storage there-of.This phenomenon exists in other countries,such as the USA:paid maternity leave is also not mandated,and only a maximum maternity leave of 12 weeks is allowed[11].In contrast,in a country such as Iran,a minimum of six months of maternity leave in both the government and private sector are allowed [11].

The WHO recommends that all babies should be exclusively breastfed for the first six months of life[10].Only after the baby has been exclusively breastfed for the first six months of life,the appropriate complementary foods,together with continued breastfeeding,may be introduced [10].The WHO describes exclusive breastfeeding as babies feeding on breast milk only,without introducing any commercial breast milk substitutes,any other liquids such as water or juice,or solid foods,except oral rehydration solutions,drops,and syrups of vitamins,minerals,or medicines [12].The introduction of any other commercial breastmilk products,liquids,or solid foods and breastfeeding before the age of six months is known as mixed feeding [12].Mixed feeding can cause problems such as provoking a slower growth of the cells lining the stomach and intestines,making the baby or child more susceptible to bacteria and viruses such as HIV from entering the body [13].Exclusive breastfeeding is believed to be one of the foundations of a child’s health,development,and survival,especially in a country such as South Africa,where diarrhea,pneumonia,and malnutrition are common causes of mortality in babies [12].Yet,in South Africa,only 31.6% of babies are exclusively breastfed up to the recommended six months of the baby’s life [1,14].

Exclusive breastfeeding has proven to be challenging for South African breastfeeding mothers returning to work after maternity leave.Many female employees face having to care for their babies and the financial obligation of having to return to work sooner as they would have liked[14].In South Africa,exclusive breastfeeding drastically declines after the baby is six weeks old.Introduction of commercial breast milk substitutes and other forms of liquids are often given to the baby before six months.The breastfeeding employee has to return to work soon after birth [15].Completely discontinuing breastfeeding or expressing breast milk is also common when breastfeeding employees return to work after maternity leave [16].

Despite being legally bound to allow working mothers to continue breastfeeding or expressing breast milk at work,many South African employers are either not well informed about the COGP or do not adhere to it without legal consequences [9].The South African Department of Health (DoH) has,however,made a booklet available entitled “Supporting breastfeeding in the workplace,a guide for employer and employees” [2],but the BCEA or the COGP does not enforce the guidelines.This creates ambiguity,causing neither employer nor employee to implement the DoH guidelines.Many breastfeeding mothers are still being discriminated against and are often told that they are not allowed to breastfeed or express breast milk at the workplace.Even if the employee is permitted to take breaks to breastfeed or express breast milk at work,both of these practices require strict hygiene and storage practices to prevent any harm to the health and wellbeing of the baby [17].Proper hand hygiene,sterilization of equipment,and storing expressed breast milk at the recommended temperatures are required and are also not always feasible in the workplace[17,18].However,the COGP does not give clear guidance on providing a specific site for employees to breastfeed or to express or for the storage of breast milk.Breastfeeding and breast milk expression also require privacy and a relaxed atmosphere,which is a significant component in allowing breast milk to flow[19].

Breastfeeding employees are often faced with the challenge of a space to breastfeed or express breast milk due to a lack of privacy in the workplace.Breastfeeding employees often express breast milk in toilet cubicles,open offices,conference facilities,or even storerooms,and due to this unsafe circumstance,they opt to discontinue breastfeeding altogether.Three main challenges experienced by breastfeeding mothers who want to adhere to exclusive breastfeeding are a lack of breastfeeding breaks for expressing and storing breast milk,lack of resources that promote breastfeeding,and lack of support from employers and co-workers [3].Other challenges include breastfeeding or expressing breast milk scheduling problems:babies feed on demand,and keeping to the 30-min breaks twice a day is unrealistic.Breastfeeding employees had trouble maintaining work performance and had adverse reactions from coworkers [20].Employees who have breastfeeding support in the workplace are more likely to continue exclusive breastfeeding for at least six months [20].A breastfeeding-friendly workplace and having a breast expressing break policy in the workplace can significantly increase exclusive breastfeeding adherence when returning after maternity leave [3].

This study aimed to gain an in-depth understanding of the experience of South African working mothers in the adherence to exclusive breastfeeding when returning from maternity leave.It was essential to making recommendations for employers based on the guidelines provided by the DoH [2].A breastfeeding-friendly working environment will be proposed to accommodate breastfeeding working mothers’ needs to increase the duration of exclusive breastfeeding as recommended by the WHO.

2.Methods

2.1.Research design

Qualitative research using a phenomenological approach was conducted.Using explorative,descriptive,and contextual designs,an understanding of the experience of South African working mothers in adherence to exclusive breastfeeding when returning after maternity leave was explored.This approach enabled the researchers to gain an in-depth understanding of the phenomenon.Furthermore,it provided an opportunity to probe and observe nonverbal communication cues from the participants[21].

2.2.Participants and sampling procedure

The participants attended either one of two Primary Health Care(PHC)mother and baby clinics in Rustenburg,North West Province,South Africa.The registered nurse working at the PHC mother and baby clinic acted as the gatekeeper and recruited potential participants who met the inclusion criteria.The mothers were informed about the study on the day they visited the PHC mother and baby clinic and were asked if they would be willing to participate in the study.Those who agreed to participate in the survey permitted the registered nurse to share their contact details with the researcher confidentially.Their names,surnames,and contact details were recorded on a personal spreadsheet.The researcher received the spreadsheet from the registered nurse and contacted the potential participants to arrange a venue,date,and time convenient to the participant to conduct the interviews.

In this qualitative study,eight breastfeeding working mothers were purposefully sampled.The inclusion criteria were:South African working mothers who returned to the workplace after maternity leave and wanted to continue adhering to exclusive breastfeeding of their babies aged newborns to six months old.The participants needed to be older than 18 years.Although the mothers were from different employment backgrounds,they had one aspect in common:they wanted to adhere to exclusive breastfeeding when returning to the workplace after maternity leave.All the mothers included in the study worked full-time under the South African BCEA of 2002 (No.11) [9].

2.3.Data collection

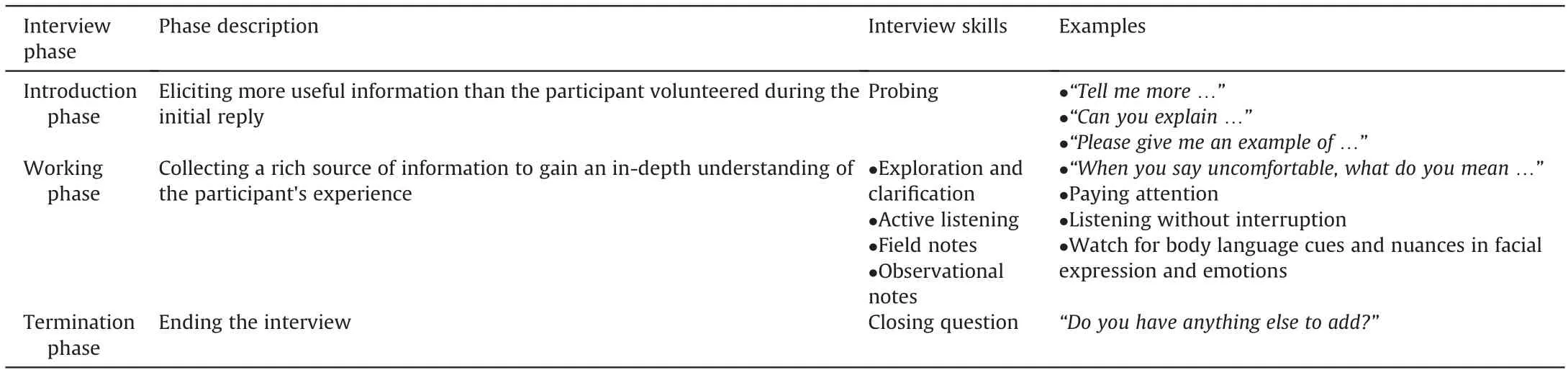

Data were collected through face-to-face,semi-structured interviews,using the interview guide (Table 1) to allow the participants to share their experience in adherence to exclusive breastfeeding.The researcher conducted the discussions in a private room at the PHC clinics to prevent external interference.The researcher conducted the interviews were trained to conduct interviews by her supervisors who are experienced in qualitative research.Two pilot interviews were conducted to enhance the conformability and credibility of the interview guide (Table 1).No adjustments were made to the interview guide after the pilot interviews.Field notes were taken during the interviews by the researcher.Each interview lasted approximately 60-90 min.The researcher conducted the interviews in English and one African language (Setswana) based on the participant’s preference.All interviews were transcribed into English and were checked by a language expert for accuracy.The interviews were audio-recorded,and field notes were also taken during the interviews to elicit conversation and enhance the comparability and credibility of the data analysis and were written directly after the interviews to avoid distraction while the interviews were taking place.The participants were encouraged to elaborate on their experience in the adherence to exclusive breastfeeding through probing and follow-up questions that were not non-threatening but thought-provoking(Table 1)[21].Data were collected until there were no new emerging themes and repetition of categories was observed.The independent coder reviewed the data and agreed that data saturation was reached after eight participants were interviewed and repetitive themes emerged.The participants and the interviewer were not related in any way.The central question posed to the participants was “How has exclusive breastfeeding been for you as a working mother?”

In Table 1,the interviews were conducted in three phases:the introduction phase,working phase,and termination phase.During the introduction phase,the participant was probed to give more useful information by asking questions such as “tell me more…”.During the working phase,the researcher aimed to understand the participant’s experience by exploration,clarification,active listening,and taking observational notes.Questions such as“when you say uncomfortable,what do you mean…”were used.During the termination phase,the interview ended using a closing question:“do you have anything else to add?” [21].

Table 1Interview guide [21].

2.4.Data analysis

The data were subsequently coded,categorized,and clustered into themes using Giorgi’s phenomenological analysis [21].The researcher familiarized herself with the interview content through listening and re-listening to the recordings and reading the field notes.Three themes emerged,and an inductive process was used to derive subthemes from the main themes.As coding occurred,the themes and subthemes were linked to one another.Observational notes of body language cues,nuances,and facial expressions assisted in supporting the subthemes.

2.5.Trustworthiness

The four criteria to ensure trustworthiness and increase rigor included credibility,transferability,and dependability [18].Credibility ensures that the study measures what it was intended to measure and truly reflects the participants’social realities [18].Credibility was ensured by using carefully designed central interview questions with follow-up questions to give the participants’true experience,engage with the participants during the interviews,and conduct member checks.Transferability refers to the capability to transfer the study’s findings to other settings and contexts using the same methods [18].Dependability refers to the research findings and methodology’s stability over time and conditions [18].Dependability was ensured through a code-re code strategy and triangulation.

2.6.Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee(REC-01-102-2018) of the University under which auspices the study was conducted.The study’s permission to conduct the study was also received from the two PHC clinics where the participants were approached,and interviews were conducted.The registered nurses acting as a gatekeeper signed a confidentiality agreement.The participants were informed that their participation was voluntary and anonymous,and they could withdraw from the study at any time.The participants gave their informed written consent before the interviews and were assured of the confidentiality of their responses.Measures were taken to ensure confidentiality,such as the use of pseudo-names to protect the real identity of the participants and to provide confidentiality of the information shared.A private room at the PHC clinic was used to conduct the interviews as it was most convenient for the participants.The researcher,supervisors,and independent coder were the only ones with access to the recordings.The audio recording will be destroyed after two years.

3.Results

3.1.Participant’s demographic information

The demographic data of the participants are presented in Table 2.The participants’ demographic data includes the participant’s type of employment,age,number of children,and the age of the last-born child.

The job descriptions included:receptionist,security guard,manager,sales representative,waitress,human resource intern,hairdresser,and cleaner.The time spent at work and away from their babies was all more than 6 h a day.All participants lived in the Rustenburg district in the North West Province in South Africa.The ages of the participants ranged between 21 and 40 years.One participant only had one child,while the others had either two,three,or four children.All the participant’s babies were still under the age of six months,with the youngest being only one month old when the mother had to return to the workplace.

3.2.Themes and subthemes

Many working mothers elected to continue breastfeeding when returning to the workplace after maternity leave [2].At work,the mothers experienced two ways to express milk:either by hand expression or using a manual or electric breast pump[2].However,the mother must continue to express breast milk in the workplace to have a continued milk supply and adhere to exclusive breastfeeding practices [2].The findings of this study indicate that working mothers had a desire to continue the adherence to exclusive breastfeeding,yet,the support in the workplace did not always enable mothers to continue with these practices.Three themes are discussed in this article being:a desire for working mothers to continue the adherence to exclusive breastfeeding,workplace support for breastfeeding mothers in the adherence to exclusive breastfeeding,and an unsuitable workplace environment for the adherence to exclusive breastfeeding.Table 3 shows the emerging themes and sub-themes discussed in this article.

Table 2Demographic data of the participants.

Table 3Emerging themes and sub-themes.

3.2.1.A desire for working mothers to continue the adherence to exclusive breastfeeding

All working mothers elected to adhere to exclusive breastfeeding and successfully managed to do so until they returned to the workplace after maternity leave.The financial obligations influenced returning to work sooner than intended.The working mothers soon realized that exclusive breastfeeding was not easy to adhere to.The mothers’experiences will be illustrated under each sub-theme in the form of quotations.

3.2.1.1.Needing to return to the workplace soon after baby’s birth.Several issues related to needing to return to the workplace soon after the baby is born emerged.Our study shows that maternity leave of less than six months was not conducive for exclusive breastfeeding.It contributed to the negative experiences ofadhering to exclusive breastfeeding when returning to the workplace,as mothers had conflicting responses.They were knowledgeable about the benefits of exclusive breastfeeding for six months but were forced by financial constraints to return to work sooner than planned and as recommended by the BCEA.Some of the participants mentioned that:

“It’s good anyway excellent before I went to work,but I’m having some,some struggles there and there…It (maternity leave) was supposed to be six months,so I decided due tofinances,I need to go back to work.” (Participant 4)

“So,everything is money,so I have to go to work.” (Participant 7)

“I have to choose to have one option,which means I have to stop breastfeeding and give formula…I don’t have any option because I will have to go to work.” (Participant 8)

Literature confirm that mothers need to return to work sooner than planned due to financial reasons,negatively influencing their intention to adhere to exclusive breastfeeding [16].

3.2.1.2.Psychological responses in the adherence to exclusive breastfeeding.Having to resort to mixed feeding or discontinuing breastfeeding completely affected the working mothers’ psychological well-being by creating anxiety.The participant mentioned:

“My heart was painful because my baby did not pick up weight as he should anymore.They said he is HIV positive.I said that is not the problem.The problem is I am mixed feeding now because of the work.It made me feel so bad.” (Participant 2)

It was revealed that the baby’s well-being was influenced when the mother started mixed feeding,which also made them feel concerned.Several mothers mentioned that they had to resort to mixed feeding because their babies simply just did not feed enough during the day.They shared their experiences:

“Atfirst,he did not want to take the bottle,sho,it made me stress so much,and then he will also get some diarrhea because of the other milk.” (Participant 6)

“Now,when I’m not there,she is notfinishing the bottle,she is eating less,then she cries too much.When I am home,she eats more because she gets the breast.She is not picking up the weight the way she must.” (Participant 7)

Another participant had to purchase formula milk as indicated by the following direct quotation:

“Now I had to buy formula milk.I don’t have the money.It makesme worry too much.” (Participant 5)

It was clear that several of the mothers experienced breastfeeding while working as stressful and even experienced shame and embarrassment.The following direct quotes confirm this:

“So many people make me feel bad about it like they just don’t accept that I am breastfeeding,and I need the time to express.Yo,it makes me so sad.” (Participant 1)

“Also,now the breastfill with milk when I am at work because I am mixed feeding now,then the breast will leak and become painful,but there is no time to go and get the milk out,I am embarrassed when my breast leak.” (Participant 4)

One of the participants experienced mixed feeding as taxing,and the following excerpt supported this:

“It makes me wish I can be with him and breastfeed him.It’s too much stress to give the formula and do the breast at the same time.”(Participant 8)

Mothers were faced with the dilemma of continuing the adherence to exclusive breastfeeding while also needing to be perceived as productive employees.Support in the workplace played a vital role in the adherence to exclusive breastfeeding.

3.2.2.Workplace support for breastfeeding mothers in the adherence to exclusive breastfeeding

Our study concluded that there was a lack of support in the workplace from both the employer and the co-workers for the mothers to continue the adherence to exclusive breastfeeding.Conditions for breastfeeding mothers were relatively the same as for other co-workers who were not breastfeeding.The mother’s experiences will be evident in their direct quotes in the following sub-themes:

3.2.2.1.Lack of support from employers and co-workers in the adherence to exclusive breastfeeding.Many mothers shared that they were not granted breaks to express breast milk,despite the BCEA.The following excerpts supported this:

“I just explain to him that I am breastfeeding,and I need to take an early lunch.That’s all I can do.” (Participant 2)

“Yes,cause I explained to my boss that the more I eat I drink cool drink right the (breast) milk becomes more right,and when the(breast)milk is full,it becomes untidy for me to have stains in front of the customer and then I had to when I feel their(breast)are full,the veins(breast ducts)become painful right,and then I ask them to cover for me (at work) quickly while I go and do it (express)quickly then I come back and work.” (Participant 4)

“No,there are no breaks for us,I must use my lunchtime.Otherwise the milk just leaks.”;“No,you just go and hide where my boss won’tsee me or know that you went away,then quickly you come back.”(Participant 5)

“You can’t tell your boss that you are taking 15 minutes to go to the bathroom to express.He will say no.” (Participant 7)

3.2.2.2.Lack of partial implementation of breastfeeding policies inthe workplace.In our study,the mothers mentioned that no special treatment was given to them as breastfeeding mothers,and it was clear that breastfeeding policies in the workplace were not reinforced.Breastfeeding employees experienced a lack of implementation of breastfeeding policies in the workplace to assist the employees in continuing with exclusive breastfeeding.The participants shared their experiences:

“No,they don’t give us the time;we need to work like all the others.No time to stop and take the milk out.” (Participant 4)

“It’s the same,mmh,it’s the same,and that’s the painful thing about my work,and I’ll be treated just like everyone who doesn’t have a baby,who don’t have children,I will arrived in the morning at seven just like any other person and knock off atfive and sometimes at six like everyone else that doesn’t have a baby and tofind that it is notfine on the baby’s side cause we are breastfeeding.”(Participant 5)

It was also evident that mothers had to use their lunch breaks for the expression of breastmilk as no extra breaks were granted:

“Eight hours work,and one-hour lunch break,that’s all,no breaks to express the milk.” (Participant 3)

“I complain to my boss that I am breastfeeding and then just ask for an early lunch to go and express the milk.” (Participant 2)

Even if the employees were granted breastfeeding breaks,the workplace environment was not suitable for the expression and storage of breast milk in several cases.

3.2.3.An unsuitable workplace environment for the adherence to exclusive breastfeeding

It appeared to be a norm in our study for the working mothers to express breast milk in undesignated facilities.Moreover,there was a lack of provision for equipment needed by the working mother to express breast milk like chairs,tables,and fridges.Several of the breastfeeding employees experienced the workplace as unsuitable for the expression and storage of breast milk.Several mothers mentioned that there is often no private space to express breast milk and that safe storage space for the breast milk is not available.The following sub-themes exemplify the mothers’ experiences:

3.2.3.1.Workplace not supportive for mothers’having to express breastmilk.In this study,it was clear that many of the workplaces were not suitable for breast milk expression.One of the participants mentioned that:

“Even if I did,I wouldn’t there because I do notfind that place clean enough.That’s what led to me mix feeding.” (Participant 1)

“No,there is no place.” (Participant 2)

Some mothers were forced to use places like the toilet and lunchrooms to express breast milk,which is not ideal:

“I use the toilet,I go sit there quickly and take the milk and go back to work,it’s not that clean,but there is nothing I can do.My baby needs the milk.” (Participant 5);“I don’t have a choice,because there is no space at work to sit and take the milk out,I just need to give the formula,I can’t afford but what must I do?”(Participant 8)

3.2.3.2.Workplace not supportive for mothers’having to store breastmilk.A mother shared,“I then put it (expressed breast milk)properly in the fridge with the food,and they (colleagues) know that there is Tony’s place.” (Participant 5)

Another mother revealed,“Aaah,no,the place is not clean.I won’t leave my milk there.I rather give the formula because the milk will get dirty if I leave it there or maybe someone will drink it because I need to put it in the fridge with the food.” (Participant 6)

4.Discussion

The study findings confirmed that although most mothers preferred maternity leave for at least six months,the BCEA of 1997[8] stipulate that the prescribed maternity leave in South Africa is four months.However,the payment of maternity benefits is governed by the South African Minister of Labor,subject to the provision of the Unemployment Insurance Act(Act 63 of 2001)[8]if her employer registers the employee.By law,employers are not obliged to remunerate employees during maternity leave.Due to the short,often unpaid maternity leave in South Africa,numerous mothers are obliged to return to the workplace almost immediately after the birth of their babies,leaving their babies in the care of someone else[22].In our study,the working mothers faced the dilemma of wanting and having to provide the best for their babies while having the responsibility of having to return to the workplace and being productive employees at the same time.The working mothers experienced financial obligations,which forced them to take shorter maternity leave,and as a result,they returned to the workplace sooner than expected.Having to return to the workplace before the baby is six months of age left some mothers with no alternative but to mix-feed their babies.Although they were aware of the implications of this,they have left no choice.Some mothers discontinued breastfeeding completely,which added to an added financial strain due to formula feeding.It was evident that breastfeeding in the workplace was experienced as stressful,and these employees developed a negative attitude towards breastfeeding.Female employees facing obstacles in the workplace are more likely to experience psychological problems such as anxiety [22].The stress of being conflicted between work and caring for their babies can ultimately influence the working mother’s psychological wellbeing and influence their work quality [23].

The BCEA under the COGP [9] stipulates that arrangements should be made for employees who are breastfeeding to have breaks of 30-min twice a day for breastfeeding or expression of breastmilk for the first six months of the baby’s life [2].Our study shows that the working mothers had a desire to continue the adherence to exclusive breastfeeding for the financial benefits it holds and e nsure their health and well-being and that of their baby.Adherence to exclusive breastfeeding is a significant contributor to the fight against child illness and death under five years [24].Discontinuing breastfeeding early is therefore associated with a substantial risk of the survival of babies [24] despite the WHO’s recommendation that all babies be breastfed exclusively for the first six months of life [10].

Although the BCEA stipulates the rights of the breastfeeding employee [9],it was evident in our study that employers do not follow the laws and guidelines [9] regarding the support of breastfeeding in the workplace.Treatment in the workplace was relatively the same for breastfeeding and non-breastfeeding employees.

The workplace is the ideal setting for implementing breastfeeding policies and practices for exclusive breastfeeding [24].The support from co-workers,access to appropriate facilities,flexible working hours,and breastfeeding breaks have been crucial in women continuing exclusive breastfeeding practices [24].Support from the employer is a critical aspect of the breastfeeding employee’s adherence to exclusive breastfeeding.Support includes permitting breastfeeding employees to express breast milk in a breastfeeding room suitable for breast milk and providing adequate storage facilities of breast milk and a positive attitude towards breastfeeding from the employer and colleagues [3].

Many female employees who breastfeed often stop breastfeeding when returning to the workplace due to a lack of a breastfeeding friendly working environment and the availability of appropriate facilities[26].This leads to the employees experiencing stress and worry,which affects the employer and their work outcome [22].

Female employees often have little or no intention to continue with exclusive breastfeeding due to lack of time and appropriate breastfeeding facilities [3].A lack of proper breastfeeding facilities in the respective workplaces led to some working mothers being forced to use alternative toilets and the staff lunchroom.Hygiene in the workplace was another determining factor for the breastfeeding employees in whether they would continue expressing breast milk or resort to alternative feeding methods.Breast milk expression requires strict hygiene and storage practices [23],and proper hand hygiene,sterilization of equipment,and storing expressed breastmilk at the recommended temperatures are also needed[18,23].

Although employees must return to the workplace soon after the baby’s birth,the benefits of providing a breastfeeding friendly environment in the workplace outweigh the cost [23].If breastfeeding is supported in the workplace,working mothers are more likely to return to work and return soon after the birth of the baby,which contributes to woman maintaining their job skills and reducing staff turnover [24].Furthermore,working mothers are also more likely to be absent from work due to fewer incidences of baby-related illnesses[25].Working mothers are also more likely to have a better sense of their physical and mental well-being at work,leading to increased productivity [25].

5.Limitations of the study

The study only included working mothers in a specific district in South Africa (Rustenburg).Future studies,including a broader context,might provide additional insight into the phenomenon that might not have been revealed in this study.This would have made the results more generalizable and to a broader population.

6.Recommendations

The working mother’s transition of returning to employment after maternity leave can be improved by the employer by offering these employees information regarding the policies and guidelines for breastfeeding in the workplace.Allowing breastfeeding employees two 30-min breaks per day,in addition to lunch and tea breaks to breastfeed their babies or to express breast milk for six months after the birth of the baby as stipulated in the COGP,can drastically improve the well-being of employees and the illness and survival rate of babies.

Some recommendations were proposed to improve the working mothers’well-being in the adherence to exclusive breastfeeding in the workplace.The employer is a critical component in promoting adherence to exclusive breastfeeding.The BCEA[8]under the COGP[9]that protects breastfeeding employees in South Africa should be implemented carefully.Employers should be able to show evidence of implementing breastfeeding policies that promote adherence to exclusive breastfeeding.The provision of lactation rooms and safe storage facilities for breast milk in the workplace can significantly increase the adherence of working mothers to exclusive breastfeeding [3].

Some of the recommendations for a breastfeeding friendly workplace include [2]:

• Appointing a workplace committee to support and facilitate breastfeeding in the workplace.

• Build awareness among employers and co-workers about breastfeeding policies and the needs of breastfeeding employees through training.

• Identify a breastfeeding advocate among the breastfeeding coworkers to champion the cause.

• Identify a suitable and private space for breastfeeding employees to express breast milk by providing a basin for handwashing,a nappy changing area or table with sanitation,a comfortable chair,available electricity outlets (should the employee use an electric breast pump),and a wall clock to assist the employee in keeping to her scheduled 30-min breaks.

• Allow flexible working duties and giving breastfeeding breaks for the expression of breast milk.

• Allocate a dedicated fridge for the storage of breast milk.

Further studies should include longitudinal studies on global policies regarding breastfeeding in the workplace and implementing these policies in the working environment.The examination of change in breastfeeding policies and the effect on exclusive breastfeeding rates,and the outcomes on the health and well-being of the mother and baby are also topics to be included in future research.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Nompumelelo Maponya:Conceptualization,Methodology,Investigation,Data curation,Writing -original draft.Zelda Janse van Rensburg:Supervision,Visualization,Writing -review &editing.Alida Du Plessis-Faurie:Supervision,Writing -review &editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Acknowledgement

We thank the participants of the study,the Primary Health Care clinics involved in the study and the University of Johannesburg.

Appendix A.Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2021.05.010.

International Journal of Nursing Sciences2021年3期

International Journal of Nursing Sciences2021年3期

- International Journal of Nursing Sciences的其它文章

- Retrospective analysis of exercise capacity in patients with coronary artery disease after percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass graft

- A qualitative study of nurses’ experiences of self-care counseling in migrant patients with heart failure

- A family nurse-led intervention for reducing health services’utilization in individuals with chronic diseases:The ADVICE pilot study

- A retrospective observational study on maintenance and complications of totally implantable venous access ports in 563 patients:Prolonged versus short flushing intervals

- The impacts of organizational culture and neoliberal ideology on the continued existence of incivility and bullying in healthcare institutions:A discussion paper

- Challenges faced by community health nurses to achieve universal health coverage in Myanmar:A mixed methods study