Three-Dimensional Mantle Flow and Temperature Structure Beneath the Shatsky Rise Ridge-Ridge-Ridge Triple Junction

ZHANG Jinchang, ZHOU Zhiyuan,*, DING Min, and LIN Jian

1) Key Laboratory of Ocean and Marginal Sea Geology, South China Sea Institute of Oceanology, Innovation Academy of South China Sea Ecology and Environmental Engineering, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou 510301, China

2) Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Guangzhou), Guangzhou 511458, China

3) China-Pakistan Joint Research Center on Earth Sciences, CAS-HEC, Islamabad 45320, Pakistan

4) State Key Laboratory of Lunar and Planetary Sciences, Macau University of Science and Technology, Macau, China

5) Department of Ocean Science and Engineering, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen 518055, China

6) Department of Geology and Geophysics, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, Massachusetts, USA

Abstract The Shatsky Rise ridge-ridge-ridge triple junction is an ancient triple junction in the Western Pacific Ocean whose initial geodynamic process is poorly understood and can only be inferred based on indirect geological and geophysical constraints. In this paper, we present three-dimensional numerical models that simulate the Shatsky Rise triple junction and calculate its coupled mantle flow and temperature structure. The mantle flow velocity field shows several distinctive features: 1) stronger mantle upwelling closer to the ridge axis and triple junction; 2) greater upwelling velocity at the faster-spreading ridges; and 3) the most significant increase in upwelling velocity for the slowest-spreading ridge toward the triple junction. The calculated mantle temperature field also reveals distinctive characteristics: 1) sharp increases in the mantle temperature with depth and increases toward the spreading ridges and triple junction; 2) the faster-spreading ridges are associated with higher temperatures at depth and identical distances from the triple junction; and 3) the slowest-spreading ridge shows the greatest increase in the along-ridge-axis temperature toward the triple junction.Compared to many present-day triple junctions with slower spreading rates, the along-ridge-axis velocity and thermal fields of the Shatsky Rise are more altered due to the presence of the triple junction.

Key words triple junction; mid-ocean ridge; Shatsky Rise; numerical modeling; mantle flow; mantle temperature

1 Introduction

Mid-ocean ridges are important surface features of the Earth’s plate tectonics (Fig.1). These ridges are fundamental plate boundaries characterized by the processes of oceanic-plate accretion and divergence and mantle upwelling(Vine and Matthews, 1963; Morgan, 1968, 1972). In the global mid-ocean ridge system, a special geological feature occurs where three mid-ocean ridges meet, namely a ridgeridge-ridge (RRR) triple junction (McKenzie and Morgan,1969). To occur, this feature requires the interaction of three divergent oceanic plate boundaries, which makes it an unusual case for studying plate tectonics and mantle dynamics.

RRR triple junctions exist in various oceans throughout the world (Fig.1) and have been subject to intensive investigation. Examples include the Rodrigues triple junction in the central Indian Ocean (Mitchell and Parson,1993), the Azores triple junction in the northern Atlantic Ocean (Searle, 1980), the Bouvet triple junction in the southern Atlantic Ocean (Sclateret al., 1976), the Galapagos triple junction in the eastern Pacific Ocean (Searle and Francheteau, 1986), and the Shatsky Rise triple junction in the western Pacific Ocean (Sageret al., 1988). The Rodrigues, Azores, Bouvet, and Galapagos are presentday triple junctions, whereas the Shatsky Rise triple junction is ancient, having formed during the Jurassic - Cretaceous. Whereas the other four triple junctions have been subjected to numerical modeling studies of their mantle flows and temperature structures (Georgen and Lin, 2002),the Shatsky Rise triple junction has not been well explored, probably because of its formation in 150 Myr, which means there are much fewer direct observational constraints with which to predict its lithospheric dynamics (Dordevic and Georgen, 2016).

Fig.1 Global map showing mid-ocean ridge triple junctions and oceanic plateaus. Annotations in red are mid-ocean ridge triple junctions; those in black are oceanic plateaus and Iceland. Background shows the satellite-predicted global topography (Smith and Sandwell, 1997).

Fig.2 Bathymetry and tectonic map of the Shatsky Rise. The bathymetry is based on satellite-predicted depths with 500-m contours (Smith and Sandwell, 1997). Solid red circles show locations of the ODP and IODP drill sites mentioned in the text. Heavy red lines show the magnetic lineations with the chron numbers labeled for reference (Nakanishi et al., 1999).Inset depicts the location of Shatsky Rise relative to Japan and nearby subduction zones (toothed lines) and the wider magnetic pattern. Note that Shatsky Rise sits at the junction of two magnetic lineation sets, including the Japanese lineations in the west trending SW-NE, and the Hawaiian lineations in the east trending SE-NW.

The Shatsky Rise is the third largest oceanic plateau on Earth (Fig.2), after the Ontong Java Plateau also in the Pacific Ocean and the Kerguelen Plateau in the Indian Ocean. It represents a typical oceanic class of large igneous provinces (LIPs). The size and age progression of the three massifs within the Shatsky Rise provide clues to hotspot chain evolution (Sageret al., 1999). However, magnetic data reveal its uniqueness due to the formation at the Pacific-Izanagi-Farallon RRR triple junction (Nakanishiet al., 1999). Recent magnetic investigation revealed the presence of linear magnetic anomalies across the entire Shatsky Rise, which indicates that this oceanic plateau formed by seafloor spreading, similar to the mid-oceanridges, although it has anomalously thick oceanic crust(Huanget al., 2018, 2021; Sageret al., 2019). This finding suggests that the RRR triple junction process was a key mechanism in the Shatsky Rise formation. In addition, its link to the mantle plume remains unclear due to the limited observations of this ancient volcanic edifice, which has been inactive since the Cretaceous. Hence, numerical modeling of the Shatsky Rise RRR triple junction is necessary to address the important problem of its dynamic behavior in creating such a large igneous edifice.

In this paper, we present three-dimensional high-resolution numerical models of the geodynamic evolution of the Shatsky Rise RRR triple junction. From these threedimensional numerical calculations, we predict the mantle velocity and temperature fields beneath this ancient oceanic RRR triple junction, and quantify the mantle flow and thermal perturbations caused by the triple junction configuration. Lastly, we compare our numerical modeling results with those of other RRR triple junctions around the globe.

2 Triple Junction Geometry

Among the types of triple junction, the RRR configuration is stable for all spreading rates and ridge orientations(McKenzie and Morgan, 1969). Therefore, a RRR triple junction provides a unique opportunity to investigate its plate kinematics, seafloor morphology, and geometric characteristics. The Shatsky Rise RRR triple junction was formed by the Pacific, Izanagi, and Farallon plates during the Jurassic-Cretaceous geologic era (Nakanishiet al., 1999).The Izanagi Plate was completely subducted to the north underneath the Aleutian Trench, and the Farallon Plate was nearly carried to the east at the Cascadia subduction zone.Today, the Pacific Plate is the only observable plate where we can observe the Shatsky Rise. From magnetic observations (Fig.2), this oceanic plateau sits at the intersection of two magnetic lineation sets (Nakanishiet al., 1999).One is the set of Japanese lineations in the west trending SW-NE, which records the fossil spreading ridges between the Pacific and Izanagi Plates. The other is the set of Hawaiian lineations in the east trending SE-NW, which documents the fossil spreading ridges between the Pacific and Farallon Plates.

Magnetic chrons (Fig.2) show that the Shatsky Rise began to develop at the location of the Tamu Massif around the time of M21 - M20 (149 - 147 Myr, Nakanishiet al.,1999; using the time scale of Gradsteinet al., 2012). The Tamu Massif is the first and largest igneous construct of all Shatsky Rise’s bathymetric highs. Radiometric dates of the igneous rock from the Tamu Massif (144 - 143 Myr,from ODP site 1213, Mahoneyet al., 2005; IODP site U1347, Geldmacheret al., 2014) match the age of the magnetic chrons of the surrounding seafloor, indicating that the Shatsky Rise formed at the Pacific-Izanagi-Farallon RRR triple junction. After the Tamu Massif, two other massifs (Ori and Shirshov) and a low ridge (Papanin) progressively developed along the path as the triple junction drifted from SW to NE. It took 23 million years to complete the formation of the Shatsky Rise, as indicated by magnetic chrons M21 - M1 (149 - 126 Myr).

Although the Pacific-Izanagi-Farallon RRR triple junction was reorganized somewhat over the entire tectonic evolutionary history of the Shatsky Rise, the spreading rates and ridge orientations remained relatively stable. The beginning of the Shatsky Rise formation from magnetic chron M21 contains the largest volcanic edifice,i.e., the Tamu Massif, but this period also shows some local plate rotation and microplate formation, leading to some complexity in the plate tectonics. After the Tamu Massif, the two other large volcanoes and low ridge formed by relatively simple and stable plate movement, which have allowed scientists to calculate the velocity vectors of the triple junction (Sageret al., 1988). Thus, we consider the period when the second largest edifice, the Ori Massif,was created to be the most representative time for defining the geometry of the triple junction. The geometry of the Shatsky Rise triple junction can, therefore, be simply obtained from the geometry of magnetic isochron M15.Sageret al. (1988) conducted a velocity-spatial analysis of the Pacific-Izanagi-Farallon RRR triple junction bounding the initial Shatsky Rise formation during M15. In this study, we applied their results combined with those of Nakanishiet al. (1999) for the spreading rates and ridge orientations (Fig.3).

Fig.3 Geometry of the Pacific-Izanagi-Farallon RRR triple junction at the initial formation of the Shatsky Rise.The values of full spreading rates and ridge orientations are taken from Sager et al. (1988) and Nakanishi et al.(1999). The finite element grids are shown as black triangles.

The tectonic evolution of Shatsky Rise incorporates many local complexities at short wavelengths, such as ridge rotation, ridge propagation, ridge jumps, transform segmentation, and microplate tectonics. Our study focuses on the long-wavelength structure of the rise. Therefore, we simplify the three spreading ridges of the triple junction into three straight lines, each with an average spreading rate and strike. Fig.3 shows the simplified Shatsky Rise triple-junction geometry for the purposes of numerical modeling. The triple junction has a ‘Y’ shape in its ridge axis geometry. It consists of three branches, the northern ridge between the Izanagi and Farallon Plates, the southeast ridge between the Farallon and Pacific Plates, and the southwest ridge between the Pacific and Izanagi Plates. The full spreading rates of these three ridges are 68 mm yr-1, 68 mm yr-1, and 54 mm yr-1, respectively, which are in the range of intermediate to fast spreading rates in the global mid-ocean ridge system. This simplified triple junction geometry is sufficient to capture the essential mantle features of the Shatsky Rise when it was formed.

3 Numerical Model Set-up

The models were calculated using COMSOL Multiphysics 5.3 software (www.comsol.com), which excels in providing solutions for multi-physics modeling. We used this software to set up finite-element numerical models that could solve for the steady-state three-dimensional mantle flow and temperature structure of the Shatsky Rise RRR triple junction. The model surface describes the divergence of the Pacific, Izanagi and Farallon Plates, with the spreading rates and directions based on the geometry of the simplified Shatsky Rise triple junction (Fig.3). The location of the triple junction was fixed at the center of the model.The motions of the three plates were calculated relative to the triple junction point and were represented by velocity vectors.

The dimensions of the model are as follows: 2000 km in length, 1583 km in width, and 150 km in height (Fig.3).This domain is large enough to accommodate the intermediate-fast spreading ridge setting of the Shatsky Rise, so that the modeled thermo-dynamic structure of the central RRR triple junction is not influenced by peripheral boundaries. The model surface and bottom were set at constant temperatures of 0℃ and 1350℃, respectively. Peripherally, the model was subject to open boundary conditions.The model grids were adaptive to horizontal resolutions in the range of 9 - 30 km and vertical resolutions of 10 - 25 km (Fig.3). The highest horizontal resolution was obtained at and nearby the location of the triple junction, and the greatest vertical resolution was obtained near the model surface, where the velocity and temperature gradients were the largest.

By combining the creeping flow and heat conduction modules, the COMSOL software solved for the mantle velocity and temperature in each model grid node using the conservation equations below:

whereuis the velocity vector,ρis the mantle rock density,tis time,pis pressure,ηis viscosity,Cpis heat capacity,Tis temperature, andkis thermal conductivity.

In the model, mantle viscosity is controlled by temperature and by the following equation:

whereη0is the mantle reference viscosity,Qis the activation energy,Ris an ideal gas constant,Tis temperature,andTpis the potential mantle temperature. Table 1 shows the parameters used in model calculations.

Table 1 Model parameters

4 Results

4.1 Mantle Flow Structure

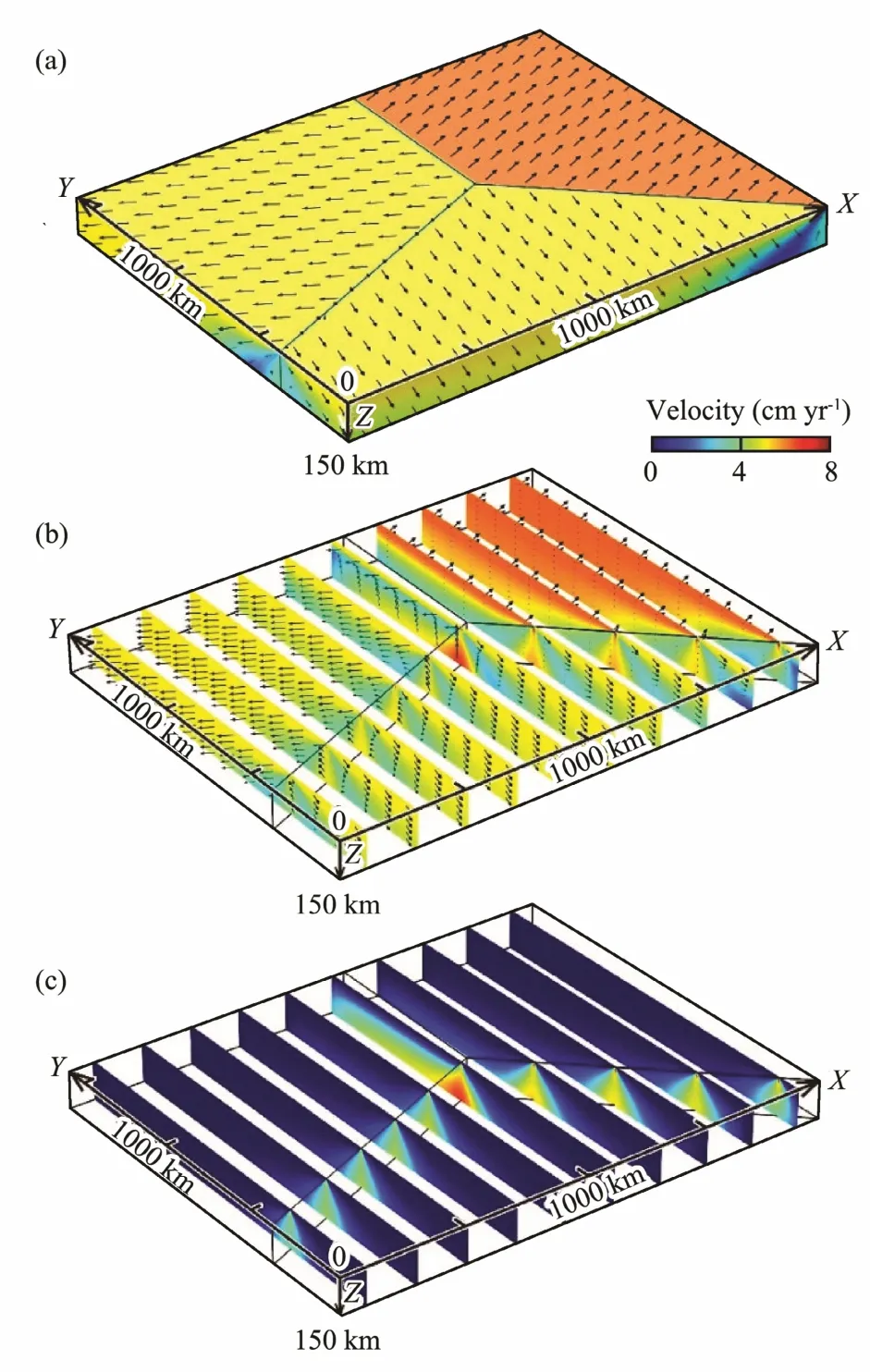

Based on the above model assumptions and boundary conditions, we calculated the steady-state velocity fields within the Shatsky Rise triple junction (Fig.4). Horizontally, the model shows divergence of the three surface plates from the triple junction. From the spreading rates of the three ridges, we know that the Farallon Plate flows the fastest, and the Pacific and Izanagi Plates have slower velocities (Figs.4a, b).

Fig.4 Velocity fields generated by a steady-state model of the Shatsky Rise triple junction. (a), surface velocity; (b),internal velocity; (c), internal upwelling velocity. Colors and arrows denote velocity magnitude and direction.

Vertically, mantle upwelling occurs underneath the three spreading ridges (Figs.4c, 9), and the upwelling velocity magnitude is larger at the faster-spreading ridges (the northern and southeast ridges), whose distances from the triple junction are identical. Mantle upwelling appears to be stronger closer to the ridge axis and the triple junction, with the greatest upwelling velocity of 65 mm yr-1at the triple junction. This maximum mantle-upwelling velocity at the triple junction is nearly equal to the fastest spreading rate(68 mm yr-1) of the ridges between the Izanagi and Farallon Plates and between the Farallon and Pacific Plates.

By taking velocity slices along the axes of the three spreading ridges, we reveal the changes in the mantle flow structure along the ridge axis. In Fig.5, with increasing distance from the triple junction, the mantle flow velocities decrease, and the upwelling mantle moves more horizontally. At a distance of 600 km from the triple junction of the three ridges, particularly at the surface, the mantle flow becomes almost horizontal. Of the three ridges, the southwest ridge with the slowest spreading rate shows the most significant increase in flow velocity toward the triple junction and the greatest extent of horizontal mantle flow,but the smallest velocity magnitude. The upwelling velocity(Figs.6 and 9) also decreases with distance from the triple junction. The upwelling velocity of the southwest ridge decreases more than those of the other two shallower ridges farther away from the triple junction. In other words, the northern and southeast ridges exhibit stronger mantle upwelling but fewer changes than the southwest ridge in both depth and distance from the triple junction.

Fig.5 Flow velocity slices along the three ridge axes of the Shatsky Rise triple junction. The northern, southeast, and southwest ridges are spreading ridges between the Izanagi and Farallon Plates, Farallon and Pacific Plates, and Pacific and Izanagi Plates, respectively. Colors and arrows denote velocity magnitude and direction. Triple junction geometry is shown in Fig.3.

4.2 Mantle Temperature Structure

The modeled temperature field of the Shatsky Rise triple junction is shown in Fig.7. Temperature increases sharply with depth, tending to exceed 1000℃ at depths greater than 10 km. Visible temperature gradients are only observed in a very thin layer (< 10 km deep) relative to the model, which is 150 km thick. The depth of the 1325℃ isothermal surface represents the onset of first-order partial melting and magmatism within the Shatsky Rise (Forsyth, 1993; Fig.7a).

Fig.6 Upwelling velocity slices along the three ridge axes of the Shatsky Rise triple junction. Plot conventions are the same as those in Fig.5.

Fig.7 Temperature field from a steady-state model of the Shatsky Rise triple junction. (a), internal thermal structure,with the purple surface representing an isothermal surface temperature of 1325℃; (b), temperature structure at the depth of 10 km.

At depth in the model, the temperature increases significantly toward the spreading ridges (Fig.7b). The axial thermal signature of the ridges is proportional to the spreading rates,i.e., higher axial temperatures correspond to faster spreading rates. However, the temperature discrepancy is modest among the three branches, with none dominating the thermal structure due to the slight differences in their spreading rates.

The temperature increases toward the triple junction.The extent of the temperature variations is coupled to the changes in the mantle upwelling velocity. Enhanced upwelling by the triple junction results in a notable temperature increase. Temperature slices along the ridge axes(Fig.8) show that at depths > 10 km in the model, the mantle temperature is broadly higher than 1300℃. However,within the thin 10km surface layer, the temperature increases toward the triple junction are more obvious along the southwest ridge than the northern and southeast ridges,which is consistent with the southwest ridge showing a more significant increase in upwelling velocity along the ridge axis (Fig.9).

5 Discussion

5.1 Characteristics of the Shatsky Rise Triple Junction

The Shatsky Rise triple junction has several characteristics that differ from many other oceanic triple junctions.First, the rise was formed more than one hundred million years ago (Sageret al., 2010, 2016), whereas a number of the triple junctions that have been studied are present-day and active with respect to both magmatism and tectonics(Fig.1). As such, the ancient Shatsky Rise triple junction is relatively difficult to investigate as it is not possible to directly measure its active geodynamic features but only infer them from the characteristics that remain since their creation and preservation over millions of years. Specifically, many oceanic paleo-edifices were formed during the Cretaceous Normal Superchron (CNS), which provides no magnetic reversals for tectonic reconstruction. The Shatsky Rise (Fig.2) is unique as its plateau was constructed prior to the CNS, so magnetic anomaly data have enabled us to decipher its tectonic history and model its mantle behavior(Sageret al., 1988; Nakanishiet al., 1999; Huanget al.,2018, 2021; Sageret al., 2019).

Fig.9 Comparison of the Shatsky Rise (upper solid) and Rodrigues triple junctions (lower dashed; Georgen and Lin,2002). SEIR, southeast Indian Ridge; CIR, central Indian Ridge; SWIR, southwest Indian Ridge.

Despite the large dimensions of the Shatsky Rise, the linear magnetic anomalies and mid-ocean ridge basalts found throughout its massive volcanoes indicate its formation by seafloor spreading (Sanoet al., 2012; Heydolphet al., 2014; Huanget al., 2018, 2021; Sageret al., 2019).The vast size of Shatsky Rise results from the high volume of magmatic flux (Sageret al., 2013), which differs from that of normal mid-ocean ridges. Thus, the Shatsky Rise triple junction appears to be composed of swollen ridges,with an overall morphology like an immense volcanic dome.Seismic profiles show a thick crust with a deep crustal root under the dome, but the crustal variations are consistent with the Airy isostasy (Korenaga and Sager, 2012;Zhanget al., 2016). The free-air gravity anomaly is small in the region, implying that the Shatsky Rise formed on a young lithosphere and was isostatically compensated (Luoet al., 2020; Zhanget al., 2020). Taken together, the magnetic, seismic and gravity observations confirm that the architecture of the plateau is the result of a triple junction with thickened mid-ocean ridges, and seafloor spreading dominating its crustal accretion.

The triple junction geometry of the Shatsky Rise is in the shape of a ‘Y’, unlike many present-day triple junctions such as the Azores, Bouvet, Rodrigues, Galapagos,Macquarie, and South Pacific triple junctions, which have a ‘T’ configuration (Fig.1). It remains unclear whether this geometric discrepancy affects the geodynamic process occurring underneath the triple junction. The spreading rates of the branching ridges, however, show a significant impact on the mantle behavior beneath the triple junction(Fig.9). For instance, triple junctions with slow-spreading ridges like the Rodrigues show less change in the upwelling velocity toward the triple junction than the Shatsky Rise. In addition, the Rodrigues triple junction exhibits sharp differences in the mantle flows and thermal structures of its ridges (Georgen and Lin, 2002), whereas the Shatsky Rise triple junction with fast-spreading branches is predicted to exhibit slightly smaller differences. In the next section, we present detailed predictions of the mantle evolution within the Shatsky Rise triple junction.

5.2 Mantle Upwelling and Temperature Rise Along the Ridges Toward the Triple Junction

At a distance of 600 km from the triple junction, the mantle upwelling and relevant thermal structure are not much affected by the triple junction, which is similar to the case of the simple divergence of two plates (Fig.8). Within 600 km of the triple junction, when nearing the triple junction, the upwelling velocity and temperature increase correspondingly along the axes of all three ridges (Figs.5,6, 8, 9). Ridges with slower spreading rates are predicted to have both greater axial velocity and temperature increases,approaching the greater upwelling rate and higher temperature of the fastest-spreading branch, with all reaching a maximum at the triple junction. Compared to the slowerspreading ridge, the axial velocities and temperatures of the faster-spreading ridges are not much different from those in the case of a single ridge. The larger variations in the velocity and temperature fields along the slower-spreading ridge indicate that it may transfer more material from the two-plate spreading to the triple junction.

As all three ridge branches of the Shatsky Rise triple junction have fast spreading rates and the rate contrast among them is not as pronounced as in many other triple junctions (e.g., Rodrigues, Azores, Galapagos), the contrasts of the along-ridge-axis velocity and thermal structure within the Shatsky Rise triple junction are accordingly smaller (Fig.9). Basically, all three ridges maintain velocity and thermal structures at distances of 600 km to 200 km from the triple junction. However, their structures are significantly altered when approaching > 200 km from the triple junction. This change is more significant than that of the Rodrigues triple junction, which has slow-spreading ridges (Fig.9). It is therefore implied that the geodynamic effects of the triple junction geometry are more significant for triple junctions with fast-spreading (e.g.,Galapagos, Shatsky Rise) than slow-spreading (e.g., Rodrigues, Azores) ridges.

5.3 Presence of Mantle Plume

The Shatsky Rise is an ancient underwater igneous edifice that has been in existence for over a hundred million years, so its underlying mantle is no longer active and the mantle dynamics cannot be directly observed. However,geologic and geophysics observations indicate the presence of a mantle plume during the formation of the Shatsky Rise. The mantle plume hypothesis is supported by the huge volumetric flux of magmatism at the Shatsky Rise(with high emplacement rate of 1.0 - 4.6 km3yr-1in the midrange of LIP fluxes), which is inferred from the tremendous dome in the topography and extraordinarily thick crust observed in tomographic images (Korenaga and Sager,2012; Zhanget al., 2016). The bathymetry of the rise shows a chain of individual volcanoes and a low ridge that progressively decreases in size, which is thought to be the transition from the plume head to the plume tail (Sageret al., 1999). IODP Expedition 324 drilled into the igneous basement of the largest volcano in the rise and obtained a core of massive basalt with a maximum thickness of 23 m, indicating rapidly erupting and highly effusive lava flows (Sageret al., 2010, 2016). Massive lava flows are less common in smaller and younger volcanoes, which imply an initial burst of magma followed by waning igneous output (Sageret al., 2013). This lithologic shift in the igneous basement also matches the prediction of the plume’s head-to-tail evolution. Paradoxically, the mantle plume mechanism predicts the occurrence of dynamic uplift, which is not observed on the Shatsky Rise due to limited subaerial evidence of such from either the boreholes or seismic profiles (Sageret al., 2010; Zhanget al.,2015).

The ancient Shatsky Rise triple junction leaves little opportunity to directly prove the existence of the mantle plume, even by tomographic study, but the geological and geophysical observations point to the presence of a plume under the triple junction when the rise was formed. The numerical modeling in this study focused on purely passive upwelling mantle flow, and did not address the upwelling associated with the mantle plume. It seems that the triple junction of mid-ocean ridges cannot alone generate excess magmatism because the divergence of the plates is not strong enough to yield such great variations in the crustal thickness. If a plume is needed, it would significantly alter the mantle dynamics of the Shatsky Rise triple junction. Modeling a plume beneath the triple junction may require dynamic simulations with more model parameters than those required for a single case of the steady-state triple junction,e.g., ridge axis geometry, areal extent, shape, volume of the edifice (Dordevic and Georgen, 2016).

5.4 Future Investigations

Our model is built on simplified assumptions,i.e., a simple triple junction and ridge segment geometry and passive mantle flow, with viscosity only dependent on temperature. Potential impact factors in the thermodynamics of the Shatsky Rise include variations in the crustal thickness, melting, strain-rate dependent viscosity, buoyancy, and detailed triple-junction and ridge-segment geometries. Although these factors might not change the overall geodynamic picture, they would likely introduce short wavelengths and local complexity to the model. Additional effects from variable viscosity, thermal buoyancy, melting,and melt retention/depletion buoyancy have been discussed in several previous studies (e.g., Georgen and Lin, 2002;Ito and Lin, 2003; Dordevic and Georgen, 2016; Bredow and Steinberger, 2018).

With regard to the geological and geophysical implications for the presence of a mantle plume, consideration of a mantle plume under the Shatsky Rise triple junction is a promising direction for future investigations. Without direct observations, plume-ridge interaction must be reconstructed back to the formation time of the Shatsky Rise.Simulating a plume is possible by adding a sustained heat flux beneath the triple junction, with the dimensions of the mantle plume determined by the radius and high heat flux values. This model could be tested using various heat flux anomaly radii and magnitudes to reproduce a melting isothermal surface, which could be considered to be the surface of the magmatism, similar to the aforementioned isothermal surface temperature of 1325℃ in Fig.7. To estimate crustal thickness, the volume of melts is integrated,which is predicted to match the actual crustal volume of the Shatsky Rise. The best match may yield the optimal model with the optimal heat flux anomaly radius and magnitude and corresponding mantle flow and thermal structures. However, as yet, this modeling proposal is oversimplified and premature. The assumption of more conditions is required,e.g., the position of the plume, degree of partial melting, temperature-pressure-strain-rate-dependent viscosity, and time-dependent evolution.

6 Conclusions

Previous studies have mostly focused on present-day triple junctions that feature actively spreading ridges. The Shatsky Rise triple junction in the western Pacific Ocean,by contrast, is an ancient triple junction that was active more than a hundred million years ago. In this paper, we presented our three-dimensional modeling of the Shatsky Rise triple junction and our calculations of the passive mantle flow and temperature fields to determine the dynamic process of the initial mantle. The mantle flow velocity field exhibits the following features: 1) stronger mantle upwelling toward the ridge axis and triple junction; 2)greater upwelling velocity beneath the faster-spreading ridges; and 3) the greatest increase in upwelling velocity by the slowest-spreading ridge toward the triple junction.The temperature field predicts the following features: 1)sharp increases in temperature with depth and increases toward the spreading ridges and triple junction; 2) the faster-spreading ridges are related to higher temperature at depth; and 3) the greatest temperature increase by the slowest-spreading ridge along the ridge axis towards the triple junction. All three ridges within the Shatsky Rise generally maintain their velocity and thermal structures from hundreds of kilometers away up to the position of the triple junction, but are significantly altered by the presence of the triple junction. Therefore, the geodynamic effects of the triple junction geometry were found to be significant for fast-spreading triple junctions like the Shatsky Rise.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2018YFC0309800), the China Ocean Mineral Resources R&D Association (No. DY135-S2-1-04), the Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Guangzhou) (No. GML2019ZD 0205), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Nos. 2021B1515020098 and 2021A1515012 227), the National Natural Science Foundation of China(Nos. 41776058, 41890813, 41976066, 91858207 and 418 06067), the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Nos. ISEE20 19ZR01, QYZDY-SSW-DQC005, 133244KYSB20180029,131551KYSB20200021, Y4SL021001, and XDB4100000 0), and the China National Space Administration (No. D02 0303).

Journal of Ocean University of China2021年4期

Journal of Ocean University of China2021年4期

- Journal of Ocean University of China的其它文章

- Environmental Drivers of Temporal and Spatial Fluctuations of Mesozooplankton Community in Daya Bay,Northern South China Sea

- The Nitrogen-Cycling Network of Bacterial Symbionts in the Sponge Spheciospongia vesparium

- Improvement on the Effectiveness of Marine Stock Enhancement in the Artificial Reef Area by a New Cage-Based Release Technique

- Relationship Between Shell Color and Growth and Survival Traits in the Pacific Oyster Crassostrea gigas

- Comparison of the Digestion and Absorption Characteristics of Docosahexaenoic Acid-Acylated Astaxanthin Monoester and Diester in Mice

- Morphology and Molecular Phylogeny of Two Marine Folliculinid Ciliates Found in China (Ciliophora, Heterotrichea)