The Nitrogen-Cycling Network of Bacterial Symbionts in the Sponge Spheciospongia vesparium

HE Liming, KARLEP Liisi, and LI Zhiyong,2),*

1) Marine Biotechnology Laboratory, State Key Laboratory of Microbial Metabolism, School of Life Sciences and Biotechnology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai 200240, China

2) Joint International Research Laboratory of Metabolic & Developmental Sciences, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai 200240, China

3) Department of Chemistry and Biotechnology, Division of Gene Technology, Tallinn University of Technology, Estonia

Abstract The microbes associated with sponges play important roles in the nitrogen cycle of the coral reefs ecosystem, e.g., nitrification, denitrification, and nitrogen fixation. However, the whole nitrogen-cycling network has remained incomplete in any individual sponge holobiont. In this study, 454 pyrosequencing of the 16S rRNA genes revealed that the sponge Spheciospongia vesparium from the South China Sea has a unique bacterial community (including 12 bacterial phyla), dominated particularly by the genus Shewanella (order Alteromonadales). A total of 10 functional genes, nifH, amoA, narG, napA, nirK, norB, nosZ, ureC, nrfA,and gltB, were detected in the microbiome of the sponge S. vesparium by gene-targeted analysis, revealing an almost complete nitrogen-cycling network in this sponge. Particularly, bacterial urea utilization and the whole denitrification pathway were highlighted.MEGAN analysis suggests that Proteobacteria (e.g., Shewanella) and Bacteroidetes (e.g., Bizionia) are probably involved in the nitrogen cycle in the sponge S. vesparium.

Key words Spheciospongia vesparium; bacterial symbionts; 454 pyrosequencing; functional gene analysis; nitrogen-cycling network

1 Introduction

The nitrogen cycle is a crucial component of the biogeochemical cycles in the oceans, which controls the productivity of the oceans and results in production and consumption of greenhouse gases (Herbert, 1999; Zehr and Kudela, 2011; Zhouet al., 2018). Coral reefs are referred to as the rainforests of the sea; however, they prosper in the environment where the available supply of nitrogen is very limited. This phenomenon is known as the ‘coral reefs paradox’ (Sammarcoet al., 1999), indicating that there is a specific nitrogen cycling strategy operating in the coral reefs.

Sponges (Porifera) have evolved more than 600 million years ago and they represent the second largest sessile component in the coral reefs. They establish close associations with a wide variety of microorganisms, including viruses, bacteria, archaea, fungi,and protists, collectively forming holobionts (Heet al., 2014; Thomaset al., 2016;Moitinho-Silvaet al., 2017). Sponges offer nourishment and a stable environment to these microorganisms; in exchange, the symbionts provide nutrition to their host by translocation of metabolites via primary metabolic processes (Wilkinson and Fay, 1979; Wilkinson and Garrone,1980; Ribeset al., 2012). Sponge holobionts play an important role in the marine ecosystem as a trophic link between corals and higher trophic levels: they consume the carbon and nitrogen from dissolved organic matter, the largest resource produced on reefs, and make it available to the reef fauna by expelling particulate detritus that can be subsequently consumed by detritivores; this process is vividly called the sponge loop (Hoffmannet al., 2009; de Goeijet al., 2013; Rixet al., 2018).

Currently, the functions of the community have become a major focus in sponge microbiome studies (Fanet al., 2012; Radaxet al., 2012; Liet al., 2014; Fioreet al.,2015; Williamet al., 2017), with special attention to their ecological implications (Pitaet al., 2018), particularly on the nitrogen-cycling potentials (Stegeret al., 2008;Turqueet al., 2010; Hanet al., 2013; Liet al., 2013).Sponge-symbiotic microbes are significant from an ecological standpoint due to their interactions with the sponge host and the environment (Pitaet al., 2018). For example, microbes in sponge holobionts have been proven to assimilate and release dissolved inorganic nitrogen,i.e., ammonia, nitrite, and nitrate (Bayeret al.,2008; Hoffmannet al., 2009). The availability of such substrates depends on diverse nitrogen transforming reactions that are carried out by complex networks of metabolically versatile microorganisms (Kuyperset al., 2018).Important achievements have been obtained in the revelation of nitrogen assimilation and transformation potentials of sponge symbionts, regarding processes such as nitrogen fixation (Mohamedet al., 2008; Ribeset al., 2015; Liet al., 2016), urea utilization (Suet al., 2013), aerobic ammonia oxidation (nitrification) (Sayavedra-Sotoet al.,1994; Rotthauweet al., 1997; Bergmannet al., 2005;Bock and Wagner, 2006; Mohamedet al., 2010; Caranto and Lancaster, 2017; Danget al., 2018), anaerobic ammonia oxidation (anammox), and denitrification, by detecting the functional genes related to the nitrogen cycle(Bayeret al., 2008; Stegeret al., 2008; Sieglet al., 2011;Hanet al., 2013), nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA)(Einsleet al., 2011; de Voogdet al., 2015), and specific bacterial species,e.g., anammox bacteria and nitriteoxidizing bacteria (NOB) (Bayeret al., 2008; Hoffmannet al., 2009; Mohamedet al., 2010; Kuyperset al., 2018).The potential of bacterial symbionts of the spongeSpheciospongia vespariumto release N2has been indicated in our previous study of the phylogenetic diversity and abundance analyses of denitrification genes,nirKandnosZ(Zhanget al., 2013).

Fanet al. (2012) revealed that analogous enzymes of denitrification and ammonia oxidation pathways may be dominant in the bacterial communities of different sponge species by metagenomic analysis. The nitrogen cycle among sponges, including nitrification, denitrification,and anammox, was reported inGeodia barrettiby Hoffmanet al. (2009). Recently, a partial nitrogen-cycling network of the microbiota of the deep-sea spongeNeamphius huxleyiwas revealed using metagenomic analysis(Liet al., 2014). However, knowledge of the whole nitrogen-cycling network within a single sponge holobiont still remains limited.

As a major component of the shallow benthic habitats,S.vespariumplays important roles in the near-shore ecosystems (Swain and Wulff, 2007),e.g., forming patch bioherms (Wiedenmayer, 1978) and being an important refuge for juvenile and adult invertebrates and fish populations (Westingae and Hoetjes, 1981).S. vespariumhas fast pumping rate (Weiszet al., 2008), enhancing the effect on the surrounding environment caused by the elements transformation occurring within the sponge, as has been shown for some sponge species (Southwellet al.,2008).S. vespariumis widespread in the China South Sea.We have detected nitrogen-cyclingnirKandnosZgenes inS. vesparium(Zhanget al., 2013). In particular, the Real-time qPCR analysis ofnirKandnosZgenes showed thatS. vespariumhad higher abundance ofnirKandnosZgenes than other South China Sea spongese.g.,Amphimedon queenslandicaandIotrochotasp. Here we try to reveal the potential bacterial pathways involved in the nitrogen cycle in the spongeS. vespariumby 16S rRNA and functional genes analysis, thereby providing insights into the nitrogen-cycling network of the phylogenetically diverse bacteria inhabiting a sponge holobiont.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Sampling

Three samples from an individual of the spongeS. vespariumwere collected by scuba diving from the coral reefs near Lingshui in the South China Sea (110°10´E,18°24´N) at a depth of about 5-10 m. The samples were transferred to sterile plastic bags containing seawater and immediately transported to the laboratory in ice boxes.Samples were cut into small pieces of about 20-30 mg each, washed three times using filter-sterilized artificial seawater (ASW) (1.1 g CaCl2, 10.2 g MgCl2·6H2O, 31.6 g NaCl, 0.75 g KCl, 1.0 g Na2SO4, 2.4 g Tris-HCl, 0.02 g NaHCO3, 1 L distilled water, pH 7.6) to remove the microbes from the seawater column on the sponge surface and inner cavity, and then stored at -80℃. The sponge was identified asSpheciospongia vespariumaccording to 18S rRNA gene with 99% similarity (Borchielliniet al.,2001). The 18S rRNA gene sequence acquired from the sponge samples was deposited in GenBank under the accession number KC762706.

2.2 DNA Extraction, Sequencing, and Cloning

Three replicates were used for total DNA extraction from the spongeS. vespariumsamples with the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Germany) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The purity and concentration of the DNA samples were analyzed using the Nanovue spectrophotometer (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corp., USA).

The bacterial and archaeal 16S rRNA genes were pyrosequenced using the 454 GS-FLX II Titanium platform(Roche Applied Science) with the primers 8F/533R(5’-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG/5’-TTACCGCGGC TGCTGGCAC) for bacteria and Arch344F/Arch915R(5’-ACGGGGYGCAGCAGGCGCGA/5’-GTGCTCCCC CGCCAATTCCT) for archaea. The sequences containing the ambiguous base N were abandoned using customized perl scripts. The obtained sequences were searched against SILVA database (version 106) using Megablast.The paired reads were concatenated and used for the following analysis. To obtain detailed taxonomic information, the RDP Classifier was run using a confidence threshold value of 80% (Wanget al., 2007).

The genes associated with the nitrogen cycle were amplified using corresponding primer sets shown in Table 1.Kod FX Neo DNA Polymerase (TOYOBO) was used for amplification in Mastercycler personal (Eppendorf). PCR was performed using an initial denaturation at 95℃ for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 95℃ for 20 s, annealing for 20 s (Table 1), elongation at 72℃ for 30 to 50 s, and the final elongation at 72℃ for 10 min. The size of the PCR products was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis. The PCR products were cloned with the pEasy-Blunt Cloning kit (Transgene) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The positive clones were identified by PCR and sequenced at Beijing Genomic Institute(Shenzhen) using the vector primers M13F/R on ABI 3730XL capillary sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

2.3 Statistical and Bioinformatical Analysis

Sequence data were edited with Chromas Lite version 2 (Technelysium). Distance matrices were calculated with DNA dist using the Kimura two-parameter model, assuming a transition/transversion ratio of 2 using the software package Phylip version 3.5 (Felsenstein, 1981). The sequences were assigned to OTUs based on the distance matrices using DOTUR (Schloss and Handelsman, 2005),with the similarity threshold of 95% for the functional genes and 97% for the 16S rRNA gene (Mohamedet al.,2010; Schmittet al., 2012). Species richness estimators(abundance coverage estimator (ACE) and Chao1 estimator) were calculated and rarefaction curves were created using DOTUR (Schloss and Handelsman, 2005) as well. Good’s coverage estimator (C) was calculated using MOTHUR v.1.33.3 (Schlosset al., 2009). Only one representative sequence from each OTU was selected for phylogenetic analysis. All representative sequences were used to perform blastx (Altschulet al., 1990) searches against available sequences in the non-redundant protein sequences (nr) database on the NCBI website (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). For each gene, the representative sequences of all the OTUs along with the nearest neighbors were used to construct a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree with Mega 6.0 (Jiaet al.,2015) using the default settings and the Jones-Taylor-Thornton (JTT) model. Robustness of the inferred tree topology was evaluated using 1000 bootstrap replicates.At last, MEGAN analysis of the genes involved in the nitrogen metabolism was carried out using MEGAN 5.1.0(Husonet al., 2016).

Fig.1 Bacterial diversity revealed by 454 pyrosequencing of the 16S rRNA genes found in the sponge Spheciospongia vesparium. a, phylum level; b, genus level.

Table 1 Primers used for detecting nitrogen cycling related functional genes

2.4 Sequence Accession Numbers

The 16S rRNA gene sequences identified were deposited in the NCBI SRA (Short Read Archive) database under the accession no. SRA047640. The sequences of the genes associated with the nitrogen cycle obtained in this study were deposited in the NCBI GenBank database under the accession numbers KC893559-KC893631.

3 Results

3.1 Prokaryotic Community in the S. vesparium Holobiont

A total of 16221 valid reads of bacterial 16S RNA genes were obtained from the spongeS. vespariumholobiont by 454 pyrosequencing. From these, 830 OTUs were distinguished at a cut-off of 97% sequence similarity.These sequences were allocated to 12 phyla and further to 41 genera and unclassified candidate groups (Fig.1). Proteobacteria,including Alpha-, Beta-, Delta-, Gamma-, and Epsilonproteobacteria, dominated the bacterial community with 16115 reads (more than 99% of all the reads).Particularly, the class Gammaproteobacteria was dominant (> 90%), especiallyShewanella, the sole genus belonging to the order Shewanellaceae, which was the most predominant genus with 13276 reads (81% of all the reads) in the bacterial community of the spongeS. vesparium. The remaining 11 bacterial phyla identified were Fusobacteria, Planctomycetes, Actinobacteria, Firmicutes,Cyanobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Spirochaetes, Acidobacteria, Gemmatimonadetes, Verrucomicrobia, and Lentisphaerae. No archaeal population was detected.

3.2 Nitrogen-Cycling Network in the S. vesparium Holobiont

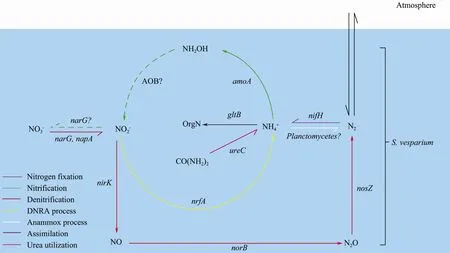

Twenty-eight primer sets targeting 13 different genes involved in nitrogen fixation, nitrification, denitrification,dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA),ammonia assimilation, anammox, and urea utilization were selected to reveal the nitrogen-cycling network (Table 1). As a result, a total of 10 functional genes:nifH,ureC,nrfA,narG,napA,nirK,norB,nosZ,amoA, andgltB, were detected in the microbiome of the spongeS.vesparium(Table 2).

Table 2 Information about the functional gene analysis of the bacterial genes involved in the nitrogen cycle

Fig.2 Phylogenetic trees based on the amino acid sequences derived from nifH (a) and nrfA (b) sequences. The numbers at the nodes represent bootstrap values. The sequences obtained in this study are marked with a triangle. Bootstrap values below 50 are not shown.

ThenifHgene, which is important for nitrogen fixation,was successfully PCR-amplified using the nifHF/nifHR primer pair (Table 2); however, only one unique OTU was recovered from 20 clones. Phylogenetic relationship of thenifH-deduced amino acid sequence to the reference sequences from sponges and seawater samples found in NCBI nr database is shown in Fig.2a. Interestingly, this OTU was most closely related to the truffle clone TM 8cl16mRNA, rather than any marine group.

For urea utilization, a total of 31 uniqueureCOTUs were obtained by sequencing 61 clones of the gene library constructed using the primer pair L2F/L2R (Table 2). In the phylogenetic tree (Fig.3),ureCOTUs fell into 5 groups. Particularly, ureC17 was closely related toMethylobacterium extorquensstrain AM1.

Fig.3 The phylogenetic tree based on ureC-deduced amino acid sequences. Bootstrap values 50% or above are shown at the respective nodes. The sequences obtained in this study are marked with a triangle.

ThreenrfA(DNRA) OTUs were recovered from 23 clones (Table 2). First, nrfA1 clustered withBizionia argentinensisJUB59 from the surface water of Antarctica,which belongs to the marine clade of the family Flavobacteriaceae, and then with nrfA2 (Fig.2b). However,nrfA3 was almost identical toShewanella balticaOS183.Similarly, for theamoAgene needed for ammonia oxidation, only 3 unique OTUs were obtained. The phylogenetic tree (Fig.4a) indicated that amoA1 and amoA3 were closely related to the marine spongeIrcinia strobilinaclone IS-amoA-05, whereas amoA2 was closely related to a clone from a coral. Four OTUs determined by thegltBgene (taking part in ammonia assimilation) sequences were identified, all of them clustered together withOceanimonassp. strain GK1 (Fig.4b).

Fig.4 Phylogenetic trees based on the amino acid sequences derived from amoA (a) and gltB (b) sequences found. The number represents bootstrap values at the nodes of the ML tree. The sequences obtained in this study are marked with a triangle. Bootstrap values > 50 are shown.

Fig.5 The phylogenetic tree based on napA-deduced amino acid sequences. Bootstrap values 50% or above are shown at the respective nodes. The sequences obtained in this study are marked with a triangle.

Fig.6 Phylogenetic trees based on the amino acid sequences derived from narG (a), nirK (b), norB (c), and nosZ (d) sequences found. The number represents bootstrap values at the nodes of the ML tree. The sequences obtained in this study are marked with a triangle. Bootstrap values > 50 are shown.

For the genes having their roles in denitrification,narGandnapAgenes were successfully PCR-amplified by primers narG1960f/narG2650r and napAV67F/napAV67 R, respectively. In total, twentynapAOTUs were detected from 45 clones. According to the phylogenetic analysis, these OTUs fell into 5 different groups (Fig.5),most of which contained clones from denitrifying estuarine sediment. Three unique OTUs fornarGgene were detected (Table 2). The phylogenetic tree (Fig.6a) indicated thatnarG1 and narG2 grouped together, whereas narG3 deviated more from the references. Two uniquenirKOTUs were detected (Table 2), both clustered into the marine group (Fig.6b); nirK1 was closely related to the sponge clone K11 and the coralTubastraea coccineaclone TcnirK-1, while nirK2 showed close affinity to the sponge clone K211. FornorB, a total of 4 unique OTUs were detected (Table 2). All thenorBOTUs clustered into two groups according to the phylogenetic analysis.Particularly, group II consisted of threenorBOTUs. In contrast,norB4 alone was affiliated to group I (Fig.6c).Only two uniquenosZ(encoding the nitrous-oxide reductase) OTUs were detected (Table 2), both were affiliated with sponge-derived sequences (Fig.6d).

MEGAN analysis of functional genes showed that Proteobacteria, especially the Gammaproteobacteria,might be involved in the nitrogen cycle in the spongeS.vesparium(Fig.7). For example, the roles of the generaShewanellaandMarinomonasin urea utilization,Oceanimonasin ammonia assimilation, the orders Alteromonadales and Vibrionales, and the genusPseudomonasin denitrification were suggested. Meanwhile, Bacteroidetes(Bizionia) might be involved in urea utilization and the DNRA process.

Taken together, bacterial nitrogen-cycling network in the spongeS. vespariumwas revealed by functional gene and bacterial diversity analyses in this study (Fig.8).Thoughhzo,hao, andnxrAgenes were not detected in the spongeS. vesparium, the related processes,e.g., anammox and nitrification, might be carried out by possible anammox bacteria,e.g.,Planctomycetes, and the aerobic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB).

Fig.7 MEGAN analysis based on nitrogen cycling gene sequences. Algorithm of the lowest common ancestor (LCA) was utilized to assign functional genes sequences in the taxonomy from a subset of the best scoring matches in the BLAST result. The scale of circles is showed on square-root of reads. The color represents different nitrogen-cycling genes.

Fig.8 Bacterial nitrogen-cycling network in the S. vesparium holobiont. A dotted line indicates that the process probably occurs because of specific bacterial species even though the functional gene is not detected.

4 Discussion

As the functional gene analysis can provide useful information about the nitrogen cycle in sponge holobionts(Fanet al., 2012; Hanet al., 2013), the genes associated with the nitrogen-cycling network were analyzed in this study to reveal the potentially active pathways in the bacterial symbionts of theS. vespariumholobiont.

4.1 Ammonia as a Loop Node in the Nitrogen Cycle

Nitrogen fixation has been shown to occur in the symbionts of marine sponges (Mohamedet al., 2008; Ribeset al., 2015; Liet al., 2016). Shieh and Lin (1994) described that a member of the family Vibrionaceae, associated with the marine spongeHalichondriasp., was involved in nitrogen fixation. Moreover, Mohamedet al. (2008) observed the expression of thenifHgene and identified that Alpha-, Beta-, and Gammaproteobacteria,Frankiaspp.,Cyanobacteria, andsome anaerobic bacteria were responsible for the nitrogen fixation in marine sponges. ThenifHsequences identified in the present study share 98%sequence identity withArcobacterYP_005552226, suggesting thatArcobacter, belonging to the Epsilonproteobacteria, might be involved in the nitrogen fixation inS.vesparium.

In addition to the ammonia production by nitrogen fixation, urease hydrolyzes urea to ammonia as well (Collieret al., 2009). The genomics of Poribacteria suggests that the bacteria could utilize urea from the environmental water or sponge host (Sieglet al., 2011; Moitinho-Silvaet al., 2017). Similarly, our previous research demonstratedureCgene expression of bacteria associated with

Xestospongia testudinaria(namelyProteobacteria,Magnetococcus,Cyanobacteria, andActinobacteria), along with urease activity ofMarinobacter litoralisisolated from the sponge (Suet al., 2013). In the current investigation, phylogenetically diverseureCgenes were observed, indicating the high potential of the bacterial symbionts in the spongeS. vespariumto utilize urea. The OTUs identified by theureCgene corresponded to Alpha-, Beta-, Gammaproteobacteria, and Bacteroidetes,which is also consistent with the findings of Bakeret al.(2009) (Fig.3). Notably, most of the sequences of theureCgene closely matchedPseudoalteromonas, the second predominant bacterial genera in the spongeS. vesparium(Fig.1b).

The detection of thenrfAgene in the spongeS. vespariumsuggests that the sponge bacteria might convert nitrate to ammonia by the DNRA process. Atkinsonet al.(2007) showed thatShewanella oneidensiscan reduce nitrite and hydroxylamine to ammonium. Similarly, theShewanellawe identified as the predominant component of the bacterial community ofS. vesparium, could probably conduct the DNRA process, since anrfAgene almost identical to that ofShewanella balticaOS183 was identified.

ThegltBgene (encoding glutamine synthase) was used as a molecular marker to identify ammonia-assimilating bacteria (Templeet al., 1998); applying that to a sponge holobiont for the first time, we detected OTUs related toOceanimonassp. (Gammaproteobacteria), which indicates the possibility of ammonia assimilation inS. vesparium’s microbiota (Fig.4b).

The presence of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB)was confirmed by finding the gene encoding ammonia monooxygenase (amoA). The corresponding sequences found in the spongeS. vespariumaffiliated with the order Nitrosomonadaceaeof Betaproteobacteria, which is consistent with previous reports from other sponges (Bayeret al., 2008; Hanet al., 2013). It has been shown that archaea may participate in the ammonia oxidation in sponges as well (Bayeret al., 2008; Stegeret al., 2008; Turqueet al., 2010); however, no ammonia oxidizing archaea were detected in the shallow-water spongeS. vesparium.

4.2 Nitrite as a Loop Node in the Nitrogen Cycle

Concerning the reactions of oxidizing hydroxylamine to nitrite and further into nitrate by nitrite oxidoreductase,we didn not find anyhaoornxrgenes in the spongeS.vesparium. However, it has been shown that AOB possess thehaogene (Arpet al., 2002; Schmidet al., 2008; Vajralaet al., 2013), therefore, AOB inS. vespariummight perform the conversion of hydroxylamine to nitrite.

To our knowledge, thehzogenehas not been used to detect anaerobic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AnAOB) in sponges before; although, AnAOB have been detected by 16S rRNA gene analysis from several sponge species(Mohamedet al. 2010). The bacterial phylum Planctomycetes is thought of as the main group of microorganisms conducting the anammox process (Baeet al., 2010;Mohamedet al., 2010). In this study, a total of 4 genera of Planctomycetes,includingBlastopirellula,Planctomyces,Phycisphaera, andRhodopirellula, were detected in the spongeS. vespariumby 16S rRNA gene analysis(Fig.1b).Blastopirellula,Planctomyces, andRhodopirellulaare putative anammox bacteria (Baeet al., 2010),thus the anammox process probably occurs in the spongeS. vesparium,even though thehzogene was not detected.

In general, nitrite oxidizers fall into five genera:Nitrobacter,Nitrococcus,Nitrospina,NitrospiraandNitrotoga(Spieck and Bock, 2005; Alawiet al., 2007). However, nitrite-oxidizing bacteria have seldom been found in sponges. For example, Fanet al. (2012) detected nitrite-oxidizingNitrospirafrom only two sponge species.In this study, thenarGgene was detected, even though none of these nitrite-oxidizing genera mentioned above were identified in the spongeS. vesparium(Fig.1), suggesting the possible oxidation of nitrite to nitrate by unidentified Gammaproteobacteria in the microbiota ofS.vesparium.

When a sponge stops pumping, its tissues become hypoxic or even anoxic, which creates the microenvironment suitable for denitrification. The present study suggests a possible complete denitrification pathway (from nitrate or nitrite to N2) mediated by bacteria in the microbiota of the spongeS. vespariumby the detection of the functional genesnarG,napA,nirK,norB, andnosZ(Table 2; Fig.8). The nitrate and nitrite for denitrification might be obtained either from the environmental seawater or from the nitrifying prokaryotes residing within the sponge (Smedileet al., 2013). Among the denitrification genes detected, thenapAgene was the most phylogenetically diverse, indicating the existence of multiple strategies for reducing nitrate to nitrite by various bacteria. It is well known that the genusShewanellais able to denitrify nitrate or nitrite (Van Spanninget al., 2005), which is in accordance with the detection of abundantnapAgenes closely related to those ofShewanellasp. in this study(Fig.5).Concerning nitrite reduction, Hanet al. (2013)noted thatnirKgenes found from the deep-sea spongeLamellomorphasp. affiliated with Alpha- and Betaproteobacteria. Similarly, in this study, thenirKgene sequences found in the spongeS. vespariumalso belong to Alpha- and Betaproteobacteria.

Some bacterial groups with functional genes may be rare in the microbial communities associated withS.vesparium, thus, whether the detected bacteria with nitrogen-cycling genes really play role in the nitrogen cycle ofS. vespariumneed more evidence. To gain further insight into thein situfunctioning of the nitrogen cycle in the spongeS. vesparium, in-depth investigations using metatranscriptomics and metaproteomics (Mohamedet al.,2008; Luteret al., 2014; Moitinho-Silvaet al., 2014),together with the analysis of inorganic and organic nitrogen in the surrounding sea water, will be conducted in the future.

5 Conclusions

The spongeS. vespariumhosts 12 bacterial phyla, the class Gammaproteobacteria making up the mayor part of the community (> 90%); particularly,Shewanellasp.comprises over 81% of microbial diversity in this sponge.Ten nitrogen cycle related genes,nifH,amoA,narG,napA,nirK,norB,nosZ,ureC,nrfA, andgltB, were identified, indicating a possible nitrogen-cycling network,with ammonia and nitrite as the prominent loop nodes,operated by bacteria in theS. vespariumholobiont. Particularly, bacterial urea utilization and the whole denitrification pathway were highlighted. According to the MEGAN analysis of these genes, the predominantShewanellais probably involved in the nitrogen cycle. Interestingly, the potential of Bacteroidetes (e.g.,Bizionia),although found with low abundance, to take part in the nitrogen cycle was also indicated.

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Nos. 31861143020, 41776 138) was used to conduct this research and is greatly appreciated.

Journal of Ocean University of China2021年4期

Journal of Ocean University of China2021年4期

- Journal of Ocean University of China的其它文章

- Environmental Drivers of Temporal and Spatial Fluctuations of Mesozooplankton Community in Daya Bay,Northern South China Sea

- Improvement on the Effectiveness of Marine Stock Enhancement in the Artificial Reef Area by a New Cage-Based Release Technique

- Relationship Between Shell Color and Growth and Survival Traits in the Pacific Oyster Crassostrea gigas

- Comparison of the Digestion and Absorption Characteristics of Docosahexaenoic Acid-Acylated Astaxanthin Monoester and Diester in Mice

- Morphology and Molecular Phylogeny of Two Marine Folliculinid Ciliates Found in China (Ciliophora, Heterotrichea)

- Comparative Transcriptome Analysis of Heart Tissue in Response to Hypoxia in Silver Sillago (Sillago sihama)