Recent updates of therapeutic strategy of esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma

Suguru Maruyama, Yu Imamura, Yasukazu Kanie, Kei Sakamoto, Daisuke Fujiwara, Akihiko Okamura, Jun Kanamori, Masayuki Watanabe

Department of Gastroenterological Surgery, Cancer Institute Hospital of Japanese Foundation of Cancer Research, Tokyo 135-8550, Japan.

Abstract The incidence of esophagogastric junction (EGJ) adenocarcinoma has been increasing in Asian countries. Despite the recent advances in multidisciplinary treatments, EGJ adenocarcinoma remains aggressive with unfavorable outcomes. Regarding surgical strategy, EGJ adenocarcinoma arises between the esophagus and the stomach, and thus tumor cells spread through the lymphatic system both upward to the mediastinum and downward to the abdomen. Nevertheless, an optimal extent of lymphadenectomy remains controversial. Regarding drug therapy, the latest topic in gastric and EGJ adenocarcinoma is trastuzumab deruxtecan, which is an antibody-drug conjugate consisting of an anti-HER2 antibody. In addition, many clinical trials have recently demonstrated the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Meanwhile, recent advances in sequencing technology have revealed that gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma could be categorized into four molecular subtypes: epstein-Barr virusassociated, high-level microsatellite instability, genomically stable, and chromosomal instability tumors.Furthermore, these subtypes show distinct clinical phenotypes and molecular alterations. We review the current surgical strategy and drug treatment such as molecular-targeted agents, immune checkpoint inhibitors, and molecular-subtype-based therapeutic strategies in EGJ adenocarcinoma. Clinical and molecular characteristics and response to immune checkpoint inhibitors differ among molecular subtypes. Treatment strategies based on molecular subtypes may be clinically beneficial for patients with EGJ adenocarcinoma.

Keywords: Esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma, Barrett’s esophagus, microsatellite instability, molecular subtype

INTRODUCTION

In western countries, the incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction (EGJ) has dramatically increased in the last few decades[1-3]. In Asia, the prevalence of this tumor seems to be rising, asHelicobacter pyloriinfections become less common[4,5]. Despite the recent improvements in next generation sequencing techniques and molecular targeting treatments, EGJ adenocarcinoma remains an aggressive malignant disease with unfavorable outcomes. Regarding surgical management of this tumor, an optimal extent of lymphadenectomy is still controversial. EGJ adenocarcinoma including Barrett’s adenocarcinoma,and adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia with esophageal invasion[6]shares molecular characteristics with gastric adenocarcinoma[7,8], whereas tumor cells can spread more widely than gastric cancer due to the bidirectional lymphatic drainage routes (mediastinal and abdominal)[9,10]. To improve the therapeutic strategy for this tumor, we review the previous studies investigating recent surgical management,particularly in lymph node dissection, and drug treatment based on molecular-targeted agents, immune checkpoint inhibitors and molecular subtype-based therapeutic strategies.

SURGICAL TREATMENT (LYMPH NODE DISSECTION)

EGJ adenocarcinoma dominates across the thorax and abdomen with various extents. In clinical practice,the Siewert classification is widely used for specifying the tumor location of EGJ adenocarcinoma as follows:Type I, the epicenter of tumor is located between 1 and 5 cm proximal to the anatomical EGJ; Type II, the epicenter is located between 1 cm proximal to and 2 cm distal from the EGJ; and Type III, a gastric tumor with esophageal invasion in which the tumor epicenter is located between 2 and 5 cm distal from the EGJ[11]. Considering that Barrett’s esophagus is a replacement of normal squamous mucosae with columnar epithelium under gastroesophageal reflux disease, Barrett’s adenocarcinoma is presumably located on the proximal side of the EGJ (Siewert Type I) compared to cardiac tumors[12].

Siewert classification is useful when surgeons select a surgical approach. Siewert Type I tumors usually need a transthoracic approach with dissection of mediastinal nodes. In contrast, Siewert Type II-III tumors can be resected by transhiatal approach alone when technically possible. Thus far, several studies have examined the clinicopathological and prognostic features by comparative analysis among Siewert Type I-III tumors[13-19]. The surgical outcome is still conflicting; some studies suggested Siewert Type III has the worst outcome, but others observed no significant differences among the Siewert types[13,16,18]. Nodal metastases[13],R0 resection[14], and lymphovascular invasion[17]appeared to be prognostic factors of EGJ adenocarcinoma.Our retrospective multicenter cohort study revealed that Siewert Type I patients with Stage II-III tumors had significantly unfavorable outcomes. Over half of such patients experienced lymph node recurrence[20].In locally advanced cases such as Stage II-III diseases, Siewert Type I tumors can spread widely through the lymphatics, leading to multi-field lymph node metastases. A hiatal hernia may concern the pattern of lymphatic spread of tumor cells in EGJ adenocarcinoma. We previously reported frequent mediastinal lymph node recurrences in EGJ adenocarcinoma cases accompanied by hiatal hernia, compared to those without hiatal hernia[21].

The Japan Esophageal Society (JES) and Japanese Gastric Cancer Association (JGCA) defined the lymph node stations for esophageal and stomach cancers, respectively[22,23]. Thus far, two studies have investigated the lymph node metastasis rate according to the lymph node stations, as a collaborative study between JES and JGCA. The first study was a multicenter retrospective study collecting EGJ tumors determined by Nishi classification, in which a tumor center is located between 2 cm proximal to and 2 cm distal from EGJ.Among 2807 cases, limiting the cases to less than 40 mm in diameter[22], there were 2384 (84.9%) cases with adenocarcinoma, 370 (13.2%) with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and 53 (1.9%) with other histological types of malignancy. Based on their observations, lower mediastinal node dissection (No. 110) might improve survival in the patients with esophagus-predominant tumors. However, they could show no conclusive result for the efficacy of middle or upper mediastinal node dissection due to the scarcity of dissected cases.

Another prospective nationwide multicenter study reported the mapping of lymph node metastasis of Nishi-defined EGJ tumors, including 332 cases of adenocarcinoma (91.5%) and 31 with SCC (8.5%)[23]. They classified regional nodes into the following three categories: Category 1 as the nodes with metastasis rate of> 10%, Category 2 as 5%-10%, and Category 3 as < 5%. They suggested a strong recommendation of lymph node dissection for Category 1 and a weak recommendation for Category 2, but no recommendation for Category 3. They indicated that the lower thoracic para-esophageal node (No. 110) should be Category 1 for tumors with esophageal invasion of more than 2.0 cm. The supradiaphragmatic node (No. 111) should be Category 1, while the posterior mediastinal node (No. 112) should be Category 2 for tumors with the esophageal invasion of more than 4.0 cm. Among the middle mediastinal nodes, the subcarinal node (No.107), the middle thoracic para-esophageal node (No. 108), and the left main bronchus node (No. 109L) were included in Category 2 for tumors with the esophageal invasion of more than 4.0 cm. In the upper mediastinum, the authors recommended dissection of the right recurrent laryngeal nerve node (106recR) as Category 1 for tumors with the esophageal invasion of more than 4.0 cm. In contrast, the left recurrent laryngeal nerve node (No. 106recL) was classified into Category 3, even in cases with significant esophageal invasion. As the recommendation is thus far based only on the metastatic rates, we need to wait for the survival outcomes for better clinical recommendations.

Regarding the surgical approach for lower mediastinal node dissection, the transhiatal approach is known to have a lower risk of pneumonia than the left thoracoabdominal approach in patients with Siewert Type IIIII tumors with less than 3 cm esophageal invasion, referring to the results of JCOG 9502, a Phase III trial[24]. Meanwhile, there is still a lack of evidence for dissection of upper to middle thoracic nodes and the appropriate surgical approaches.

DRUG THERAPY

Molecular-targeted agents

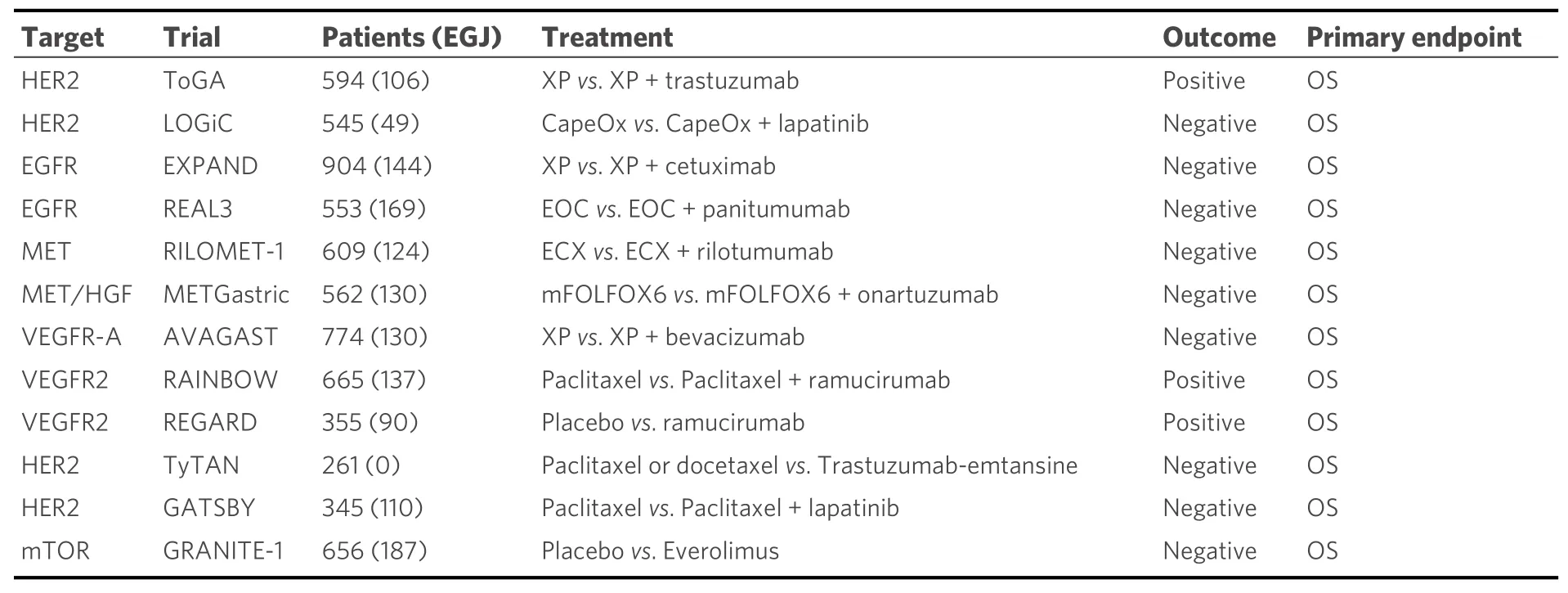

Molecular-targeted drugs have been created for various types of cancers. We summarize the previously investigated clinical trials of molecular targeting agents for EGJ and gastric adenocarcinoma [Table 1].

Table 1. Clinical trials testing targeted therapies for EGJ and gastric adenocarcinoma

Trastuzumab is a monoclonal antibody targeting human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). The ToGA trial (Phase III trial, including 106 cases with EGJ adenocarcinoma and 478 cases with gastric adenocarcinoma) assessed the safety and survival benefit of trastuzumab plus first-line chemotherapy (5-fluorouracil and platinum or capecitabine and platinum) for advanced tumors with HER2-amplified esophagogastric adenocarcinoma in 2010. HER2 amplification or overexpression was more prevalent in EGJ cancer (33.2%) compared to that in gastric cancer (20.9%) (P< 0.001). The median overall survival (OS) was significantly better in the trastuzumab plus chemotherapy group than that in the chemotherapy alone group[median 13.8 months; 95% confidence interval (CI): 12-16 monthsvs. median 11.1 months; 95%CI: 10-13 months] [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.74; 95%CI: 0.60-0.91;P= 0.0046][25]. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline recommends combination use of trastuzumab with any chemotherapeutic agents in patients with HER2-amplified or -overexpressing EGJ adenocarcinoma as well as gastric tumors.

Ramucirumab is a human immunoglobulin (Ig) G1 monoclonal antibody that antagonizes vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2. Two clinical trials have shown a survival advantage of ramucirumab,as monotherapy or combined with paclitaxel, in the second or more regiment setting for advanced EGJ adenocarcinoma. The REGARD and RAINBOW trials have successfully demonstrated the survival benefits of ramucirumab in the second-line regimen for advanced unresectable esophagogastric adenocarcinomas[26,27]. Hence, new investigational strategies adding ramucirumab may be intriguing for resectable EGJ adenocarcinoma using effective drugs for advanced setting.

Bevacizumab, a monoclonal medicine targeting vascular endothelial growth factor A, inhibits tumor progression in preclinical settings. Unfortunately, the AVAGAST trial did not show any survival benefit of bevacizumab[28-30]. Lapatinib is the dual inhibitor of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and HER2.Lapatinib showed no additional survival benefit to the combination therapy of capecitabine plus oxaliplatin in the first-line setting of HER2-amplified/overexpressing esophagogastric adenocarcinoma (the TRIO-013/LOGiC trial)[31]. Cetuximab, an EGFR antibody, is widely used for the patients with advanced diseases of head and neck, non-small-cell lung, andKRASwild-type colorectal cancers[32-35]. The EXPAND trial has failed in demonstrating a survival benefit in the first-line use of cetuximab in addition to capecitabine plus cisplatin[36]. Panitumumab, which is another monoclonal antibody targeting EGFR, significantly improved progression-free survival in patients with advanced colorectal cancer[37]. However, no survival benefit was observed in adding panitumumab to a triplet regimen using epirubicin, oxaliplatin, and capecitabine(REAL3 Phase III trial)[38]. Additionally, MET inhibitors, including rilotumumab and onartuzumab, and everolimus (a mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor) conferred no survival benefits in EGJ cancer[39-41].

As described above, many Phase III studies using molecular-targeted drugs have reported negative results.The latest topic regarding molecular-targeted agents in gastric and EGJ adenocarcinoma is the DESTINYGastric01 trial. Trastuzumab deruxtecan (DS8201) is an antibody-drug conjugate consisting of an anti-HER2 antibody, a cleavable tetra-peptide-based linker, and a cytotoxic topoisomerase I inhibitor. The DESTINY-Gastric01 trial in 2020 (Phase II trial, including 24 cases with EGJ adenocarcinoma and 163 cases with gastric adenocarcinoma) evaluated the objective response of trastuzumab deruxtecan compared with chemotherapy in patients with HER2-positive advanced gastric cancer. Patients who progressed while they were receiving at least two previous therapies, including trastuzumab, were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive trastuzumab deruxtecan or physician’s choice of chemotherapy (irinotecan or paclitaxel). An objective response was reported in 51% of the patients in the trastuzumab deruxtecan group, as compared with 14% of those in the physician’s choice group (P< 0.001). OS was longer with trastuzumab deruxtecan than with chemotherapy (median, 12.5vs. 8.4 months; HR = 0.59; 95%CI: 0.39-0.88;P= 0.01)[42].

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have emerged with remarkable anti-tumor activity against esophagogastric adenocarcinoma. Programmed death protein 1 (PD-1), PD-1 ligand 1 (PD-L1), and cytotoxic T lymphocyte protein 4 (CTLA4) are key molecules regulating the immune escape mechanism in cancer[43]. Nivolumab is a human IgG4 monoclonal antibody (mAb) against PD-1. The ATTRACTION-2 trial (Phase III) has demonstrated a significant survival prolongation of nivolumab in the third-line therapy for advanced gastric tumors[44]. In addition, the ATTRACTION-4 trial (Phase II) has demonstrated that nivolumab in combination with chemotherapy in patients with untreated unresectable advanced or recurrent gastric cancer may be a potential therapeutic option[45]. In addition, according to the recent CheckMate-649 study, nivolumab plus chemotherapy represents a new possibility for standard first-line treatment for advanced gastric, EGJ, and esophageal adenocarcinoma[46]. In addition, adjuvant administration of nivolumab has just been shown to be effective in patients with Stage II-III tumors in esophagus or EGJ cancer (CheckMate-577)[47]. Pembrolizumab is another humanized high-affinity IgG4 mAb acting against PD-1. The KEYNOTE-059 trial has reported a favorable overall response rate of 11.6%in patients with advanced gastric cancer treated with pembrolizumab in a Phase II setting[48]. However, the KEYNOTE-061 study, a Phase III trial comparing pembrolizumab with paclitaxel as the second-line treatment for advanced gastric or EGJ tumors, has failed to meet the primary endpoint of improving survival[49]. In addition, the KEYNOTE-062 study (Phase III) demonstrated that pembrolizumab or pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy was not superior to chemotherapy according to OS and progressionfree survival in patients with untreated advanced gastric cancer[50]. A Phase III trial of pembrolizumab plus chemotherapyvs. chemotherapy as neoadjuvant/adjuvant treatment for resectable gastric or EGJ adenocarcinoma is ongoing (KEYNOTE-585)[51]. Avelumab, another ICI targeting PD-L1, could not show survival benefits over chemotherapy as a third-line treatment for advanced gastric or EGJ cancer (JAVELIN Gastric 300)[52]. Meanwhile, in western countries, perioperative chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel (FLOT4) was selected for patients with locally advanced, resectable gastric and EGJ cancer[53]. A Phase II trial to evaluate the safety, efficacy, and toxicities of perioperative chemo-immunotherapy with avelumab and FLOT (fluorouracil plus leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel)is ongoing (ICONIC trial). Ipilimumab is a mAb that activates the immune system by targeting CTLA4. In a Phase II trial, the nivolumab plus ipilimumab group showed a higher OS rate than the nivolumab alone group (Checkmate-032)[54]. However, the higher incidence of immune-related adverse events after nivolumab plus ipilimumab treatment than after nivolumab alone must be considered[55].

Molecular subtype-based therapeutic strategy

Thus far, pathological classification has been a major type of tumor classification in gastroesophageal tumors. Recently, the next-generation sequencing technology developed molecular taxonomies in various types of malignancies, including gastroesophageal tumors, utilizing whole genome sequencing, whole exon sequencing, RNA sequencing, comprehensive methylation assay, and proteomic assays[8,56,57]. The Cancer Genome Atlas Network (TCGA) has demonstrated four molecular subtypes in gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma as follows; Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-associated, high-level microsatellite instability (MSIH), genomically stable (GS), and chromosomal instability (CIN) tumors[7,8].EBV-associated tumors show CpG islandmethylator phenotype displayingCDKN2Asilencing; frequent mutations inPIK3CA,ARID1A, andBCOR; and gene amplification inERBB2,JAK2/PD-L1/2, andPIK3CA[7,8]. In addition, this subtype is suggested to be immune reactive. Although EBV-associated tumors seem to account for only a small fraction of EGJ adenocarcinomas, recent comprehensive genomic analyses have suggested their sensitivity to ICIs through PD-L1 or PD-L2[7,58].

MSI-H tumors, which are uncommon in EGJ, harbor hypermutation, hypermethylation,MLH1silencing,and frequent mutations inARID1A,RNF43,PIK3CA, andKRASand are immune reactive[7,8,59]. According to an exploratory investigation utilizing the data from the Medical Research Council Adjuvant Gastric Infusional Chemotherapy trial, a favorable outcome was associated with MSI-H subtype. However, MSI-H was a predictor of chemo-refractory tumors. In addition, MSI-H is associated with less lymph node metastasis and a favorable outcome[60]. Therefore, surgery alone may be adequate to cure operable MSI-H EGJ adenocarcinoma[61]. Since hypermutated tumors produce neoantigens, MSI-H tumors are already known as immunogenic, and anti-tumor immunity is able to be activated against the neoantigens released into the tumor microenvironment[62]. Although nivolumab significantly conferred a survival advantage in a RCT involving patients with metastatic disease of esophagogastric adenocarcinoma, regardless of molecular subtypes, it may be more effective in EBV-associated or MSI-H tumors[44,58].

GS tumors commonly present diffuse-type histology defined by the Lauren classification. This subtype frequently possesses mutations inRHOAandCDH1, and oncogenic gene fusion ofCLDN18-ARHGAP26was also frequently detected[7,8]. Besides these major alterations,BRCA1-2,CTNNA1, andRAD51Cwere detected in this type of gastric adenocarcinoma[63-66]. CIN tumors can be described as characterized with structural chromosomal instability, whole-genome doubling, and oncogenic gene amplification particularly in the RTK-RAS pathway and cell cycle-related genes[7,8,67,68]. We developed a novel targeted therapy focusing onKRAS-amplification in EGJ adenocarcinoma[69].KRAS-amplified malignant cells possess a large amount of inactive KRAS-GDP. Under mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibition,KRAS-amplified tumor cells do not react due to adaptive response by mobilizing inactive KRAS-GDP to the active state of KRAS-GTP. This adaptive reaction is able to be suppressed by blocking SOS1 and SOS2, both of which are guanine-exchange factors. In addition, the protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP2 is similarly inhibited. Hence, a combination of an MEK inhibitor and SHP2 blockade may be a promising medicine for CIN-subtype in EGJ adenocarcinoma. Other molecules and immune checkpoint molecules need to be evaluated for GS or CIN tumors.

The molecular characteristics of EGJ and gastric adenocarcinoma are different. Firstly, the distribution of molecular subtypes differs across tumor locations, among EGJ (cardia), gastric (fundus/body), and gastric antrum (pylorus)[7,8]. Actually, 84.8% of EGJ adenocarcinoma (combining Siewert Type I-III tumors) were classified into CIN subtype. In contrast, MSI-H (4.2%) and EBV (3.6%) subtypes were rare in EGJ adenocarcinoma in the TCGA study[8]. In particular, no MSI-H or EBV subtype was detected in Siewert Type I of esophageal adenocarcinoma. These trends were also observed in our recent report[60]. Secondly,when focusing on CIN subtype, genetic and epigenetic alterations are different in EGJ and gastric adenocarcinoma. The TCGA esophageal study clustered CIN esophagogastric adenocarcinoma into four continuous categories, C1 (the most hypermethylated category) to C4 (the least methylated category)[8]. The most hypermethylated C1 was frequently observed in 36.6%, but the least methylated C4 was found in 4.2%in EGJ adenocarcinoma. However, in gastric adenocarcinoma, C1 was only 3.4% and C4 increased to 23.7%in fundus or body tumor. In addition, in antrum or pyloric tumor, epigenetic changes are less common compared to EGJ tumors. For instance, epigenetic silencing ofCDKN2A(also known as p16) was detected in 30%-40% of EGJ adenocarcinoma but in only 5%-6% of stomach tumors[8]. Thus, DNA demethylating agents may be a useful therapeutic strategy of EGJ adenocarcinoma. In addition, tumor suppressor gene alterations such asSMARCA4deletion/mutation,RUNX1deletion,FHITdeletion, andWWOXdeletion frequently occurred in EGJ adenocarcinoma, compared to gastric tumors[8]. Some oncogenic gene amplifications such as VEGFA copy number gain were also frequently observed in EGJ adenocarcinoma compared to gastric tumors. Administrating molecular targeting agents according to both molecular subtypes and tumor location may be one of the options in future clinical trials.

CONCLUSION

We review the current surgical strategy, evidence of molecular-targeted agents, and candidate therapeutic targets in EGJ adenocarcinoma. According two collaborative studies, lower mediastinal node dissection might improve survival, however there is still a lack of evidence for dissection of upper to middle thoracic nodes and the appropriate surgical approaches. Regarding molecular analyses, a recent comprehensive genomic analysis revealed four distinct molecular subtypes based on different carcinogenic steps.Interestingly, clinical and molecular characteristics and responses to ICIs differ between molecular subtypes.A molecular subtype-based treatment strategy may be clinically beneficial for patients with EGJ adenocarcinoma.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Wrote the manuscript: Maruyama S

Designed the research and helped to draft the manuscript: Imamura Y

Made substantial contributions to the data analysis and interpretation: Kanie Y, Sakamoto K, Fujiwara D,Okamura A, Kanamori J

Designed the research and helped to draft the manuscript: Watanabe M

All authors have revised and approved the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2021.

Journal of Cancer Metastasis and Treatment2021年8期

Journal of Cancer Metastasis and Treatment2021年8期

- Journal of Cancer Metastasis and Treatment的其它文章

- Treatment of unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma in 2021: emerging standards in immunotherapy

- AUTHOR INSTRUCTIONS

- GENERAL INFORMATION