Auricular vagus nerve acupressure for patients with emotional distress under the COVID-19 pandemic: A smartphone-based, randomized controlled trial

Peijing Rong, Lei Wang, Lingling Yu, Junying Wang, Yan Ma, Liting Wang, Suxia Li, Chunzhi Tang, Liming Lu, Liang Li, Jiazi Dong, Jiliang Fang, Liwei Hou, Zongshi Qin, Xiaolan Su0, Yufeng Zhao, Zhangjin Zhang*

1 Institute of Acupuncture and Moxibustion, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, Beijing, China.

2 Tongji Hospital of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, Hubei, China;

3 Department of Rehabilitation, Wuhan No.1 Hospital, Wuhan, Hubei, China;

4 Department of Electronic Engineering, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China;

5 National Institute of Drug Dependence, Peking University, Beijing, China;

6 Medical College of Acu-Moxi and Rehabilitation, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou, China;

7 School of Acupuncture, Moxibustion and Tuina, Liaoning University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shenyang, China;

8 Guang’anmen Hospital, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, Beijing, China;

9 School of Chinese Medicine, LKS Faculty of Medicine, the University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

10 Wangjing Hospital, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, Beijing, China;

11 National Data Center of Traditional Chinese Medicine, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, Beijing, China.

Abstract Objective:To confirm whether self-administered AVNA treatment is effective in improving emotional distress under the COVID-19 pandemic.Methods:A smartphone-based online, randomized, controlled trial was designed from 26 February 2020 to 28 April 2020 in four study sites, including Wuhan, Beijing, Shenyang, and Guangzhou of China.Local residents who had considerable emotional distress with a score of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) ≥ 9 were recruited.Participants were randomly assigned to three times of AVNA (n = 191) per day, in morning, around noon, and in evening or usual care (UC, n = 215) once daily for 14 days.The primary outcome was the response rate, which was the proportion of participants whose Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) score reduced from baseline by ≥ 50%.The assessment was conducted at baseline, 3 days, and 14 days.Results:The AVNA group had a markedly higher response rate than the UC group at 3 days (35.6% vs.24.9%, P = 0.02) and at 14 days (70.7% vs.60.6%, P = 0.02).The AVNA group showed significantly greater reduction in scores of HADS at the two measurement points and BAI at 3 days (P ≤ 0.03), with average respective effect size of 0.217 and 0.195.Participants with AVNA spent less time falling asleep and rated their sleep quality being remarkably higher than those with UC at endpoint.Conclusion:During COVID-19 pandemic period, treatment with self-administrated AVNA was more effective than UC in reducing emotional distress of isolated populations.These findings support self-administered AVNA as a treatment option for patients with emotional distress under the COVID-19 pandemic or other emergent events.

Keywords:Neurology, Psychiatry, Emotional distress, Auricular vagus nerve stimulation, COVID- 19

Background

The global spread of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has become a public health emergency of international concern.Although infectious disease management measures, including city lockdown and household isolation, have reduced the risk of the viral transmission, it has also produced considerable number of patients with emotional distress, such as anxiety, depression, and poor sleep [1].Therefore, therapeutic approaches that show effective and convenient will hold considerable promise for the treatment of emotional distress under COVID-19.

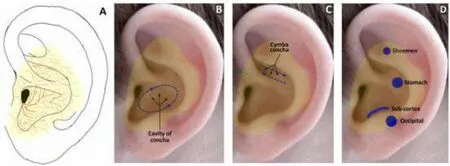

Several studies have confirmed the efficacy of acupressure in relieving insomnia of patients and emotional distress of caregivers [2-4].The external ear is a specific anatomic region where nerve fibers and terminals from the auricular branch of the vagus nerve (ABVN) are abundantly distributed in the concha and surrounding areas (Figure 1A) [5-8].Accumulating evidence from clinical studies have confirmed that stimulation of auricular acupoints is effective in improving sleep quality, and in reducing anxiety and depressed mood with low side effects [9-12].We have also demonstrated the efficacy of a non-invasive transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) in patients with emotional distress [13, 14].These studies have led to the hypothesis that selfadministered auricular vagus nerve acupressure (AVNA) might be an effective management intervention of emotional distress under the COVID-19 pandemic.

To test this hypothesis, a randomized controlled trial was conducted via a smartphone-based online miniprogram.We compared the efficacy of selfadministered AVNA treatment with usual care (UC) in reducing emotional distress of local residents during COVID-19 lockdown and household isolation in China.Breathing-focused and home-based exercise, the most frequently recommended activities at home during the COVID-19 pandemic, were included as major UC interventions [15, 16].

Methods

Settings and subjects

This smartphone-based, randomized controlled trial was conducted at Institute of Acupuncture and Moxibustion, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, Beijing; Wuhan No.1 Hospital, Wuhan; Liaoning University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shenyang, and Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine between February 26, 2020 and April 28, 2020, when a lockdown of Wuhan and household isolation in the other three cities were imposed.The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Institute of Acupuncture and Moxibustion, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences,Beijing,and registered in http://www.chictr.org.cn (Identifier: ChiCTR2000030 078) on February 22, 2020 before the first participant was recruited.Recruitment of subjects and data acquisition were conducted autonomically from the mini-program via smartphone and reorganized by Yufeng Zhao.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients were included if they met the diagnosis of emotional distress, using a Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).

Inclusion criteria included: (1) subjects aged between 18 and 75 years; (2) HADS scores ≥ 9 points during the baseline phase; (3) living in the study cities for at least half a year.

Figure 1.Distribution of the auricular branches of the vagus nerve (A) and auricular vagus nerve acupressure steps (B-D).

Those who had been diagnosed with a psychiatric illness, who had taken antipsychotic drugs, who was illiterate or who could not use WeChat, who had unstable medical conditions, infection or cutaneous lesions of the external ear, or were not able to conduct acupressure themselves were excluded.

Randomization and blinding

Eligible patients were randomly assigned to receive either self-administered AVNA or UC in a ratio of roughly 1:1.Randomization sequence was generated in the mini-program,Massage on Auricular Acupuncture Points and Get Rid of Insomnia and Stress, and stratified by sites.The event that the participant clicked the button triggered to generate the seed of random number.The time stamp of the trigger button was millisecond precision, which was triggered by the user who approached the real random process.

All investigators with at least five years of acupuncture practice were not allowed to get access to participants’ information during the study period except for one technician (Junying Wang) who was responsible for maintaining the mini-program and daily operating records.All assessments were done by participants themselves on the mini-program without investigators’ involvement.Such design ensured complete blindness of investigators to the group allocation.

Interventions and assurance of compliance

Participants in the AVNA group were instructed and trained to have three times of self-administered AVNA per day, in morning, around noon, and in evening for 14 days.This length of intervention was consistent with the mandatory self-isolation period.They were also instructed to receive one session of the UC intervention per day during the same days.To ensure compliance, participants in the UC group were instructed to receive the UC intervention as done in the AVNA group; meanwhile they were informed that self-administered AVNA would be instructed after 14 days of the UC intervention.The AVNA procedures was established based on the distribution of the auricular branch of the vagus nerve [6-8] and agreed by consensus after consulting senior acupuncturists and traditional Chinese medicine practitioners.

The self-administered AVNA consists of 3 steps (Figure 1B-D).Step 1: using the index fingertip pads to gently press and knead the cavity of concha in both clockwise and anticlockwise directions for 25-30 times in each direction; Step 2: using the index fingertip pads to gently massage the cymba concha forward and backward for 25-30 times in each direction.Step 3: using the index fingertip pads to firmly press Shenmen, Sub-cortex, Occipital, and Stomach, the 4 auricular acupoints that have particular effects in alleviating emotional symptoms and insomnia according to TCM practice [16], 1 minute for each point.Participants were advised to practice each step until a specific sensation, commonly soreness, numbness, or heaviness, should be felt, but the forces could not be too strong otherwise the skin of the ears would be injured.About 6-7 min were needed to finish all the three steps.

For the UC group, all participants received hygiene, personal protection, dietary, and sleep education at their entry into the study.Consultation was further provided upon request.Meanwhile, all participants were instructed to practice breath-focused and indoor at-home exercise.The detailed procedure of breathfocused exercise is provided in the mini-program.Indoor at-home exercise included jogging around the house and bare hand exercise, such as pushup, squats, abdominal crunches, leg lifting, side bending, and muscle stretching.Participants practiced breathfocused exercise for 5 min and the indoor at-home exercise for 30 min per day.

The evaluation scale was uploaded in the form of electronic scale in the mini-program.At the corresponding time point, patients were reminded by the mini-program to complete the scale.Participants were required to record their daily intervention and activity on the online platform.To ensure complete compliance and quality of interventions, designated site investigators (Lei Wang in Beijing, Lingling Yu in Wuhan, Chunzhi Tang in Guangzhou, Jiazi Dong in Shenyang) monitored participants’ activities via WeChat video or voice call on the daily basis.

Outcome Assessments

The primary outcome was the response rate, which was the proportion of participants whose HADS score reduced from baseline by ≥ 50%.Non-response means HADS scores reduced by <50%.Worse response means greater score after randomization.These definitions were based on the distribution of normative values for HADS score in the general population [17].

Secondary outcomes, including the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [17], Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) [18], Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [19] and Impact emergent scale-revised (IES-R) [20], were additionally used to measure the severity of anxiety, depression, and stress response to the COVID-19, respectively.Participants were also asked to record total sleep hours, time to fall asleep, number of wakeups, and sleep quality per night during the past week, which was modified from the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [21].The sleep quality was measured using a 5-point Likert self-rating scale where higher scores indicate worse sleep quality.The assessment was conducted at baseline, 3 days, and 14 days after randomization.The purpose of assessment at 3 days was to detect the short-term effects of AVNA as previous studies have suggested that acupressure could rapidly improve anxiety and insomnia [2-4].In addition, participants were required to report adverse events on the daily basis.

Sample size estimation and statistical analysis

The primary objective of this study was to determine whether self-administered AVNA treatment could produce a clinically greater efficacy response rate than UC.Our preliminary study revealed an efficacy response rate of 76% in the AVNA group versus 59% in the UC group.A sample size of 204 each group would be sufficient to detect a 17% difference in efficacy response rate between the two groups at an 80% power and a statistical level of 0.05, with the consideration of an estimated dropout rate of 20%.

The outcome analysis was carried out based on an intent-to-treat (ITT) data set, defined as the subset of participants who completed at least one session of intervention, baseline and at least one post-baseline evaluation.Interim and stopping analysis were conducted only when home isolation was cancelled according to the governmental epidemic prevention policy.

The primary outcome, HADS-defined response, non-response, and exacerbation rate, was analyzed using a multinomial generalized estimating equation model.The linear mixed-effect model for repeatedmeasures analysis was used to analyze secondary outcomes with study site and isolation days as covariates.Treatment, visit, and treatment × visit interaction served as a fixed effect.Site and interaction between site and treatment served as random effects accounting for center differences.Baseline differences in demographic and clinical characteristics were analyzed using Chi-square (χ2) test or t test.

Between-group effect size was calculated by dividing the between group difference in posttreatment means with the pooled standard deviation.The effect sizes of 0.20, 0.50, 0.80, and 1.30 represent “small”, “medium”, “large”, and “very large” effect, respectively [22].

All data were collected autonomically from the miniprogram and reorganized by Yufeng Zhao.Statistical analysis was performed by independent statisticians (Yufeng Zhao, Zongshi Qin) using SAS statistical software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).The significance level was set at a 2-sidedP< 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics of study participants

Among 975 local residents who attended screening via the mini-program from February 26, 2020 to April 28, 2020, 406 who met the inclusion criteria and were willing to participate in the study were randomly assigned to AVNA (n=191) and UC (n=215) groups; 404 (99.5%) completed all assessments and interventions as per protocol (Figure 2).Two participants who were lost to follow-up without any assessment and intervention after randomization were excluded from the data analysis.All baseline variables were well balanced between the two groups (Table 1), but significant differences in baseline outcome variables were observed across the four sites (Supplementary materials).Site hence served as a covariate in the outcome analysis.

Figure 2.Flowchart of screening and patient recruitment.A

Table 1.Characteristics of participants a

Table 2.Primary outcome of full analysis set population a

Table 3.Secondary outcomes of full analysis set population with emotional distress a

Figure 3.Primary outcomes throughout trial.Comparisons of response, non-response, and exacerbation rate between the two Groups.

Primary outcome: HADS-defined response rate

The results of HADS-defined response, non-response, and exacerbation rate are illustrated in Table 2 and Figure 3.At 3 days, the response rate of the AVNA group was significantly greater than that of the UC group [35.6% (68/191) vs.24.9% (53/213),P= 0.02].At 14 days, the AVNA group had a markedly higher response than the UC group [70.7% (135/191) vs.60.6% (129/213),P= 0.02], with remarkably lower exacerbation rate than the UC group [3.7% (7/191) vs.9.4% (20/213),P= 0.02].

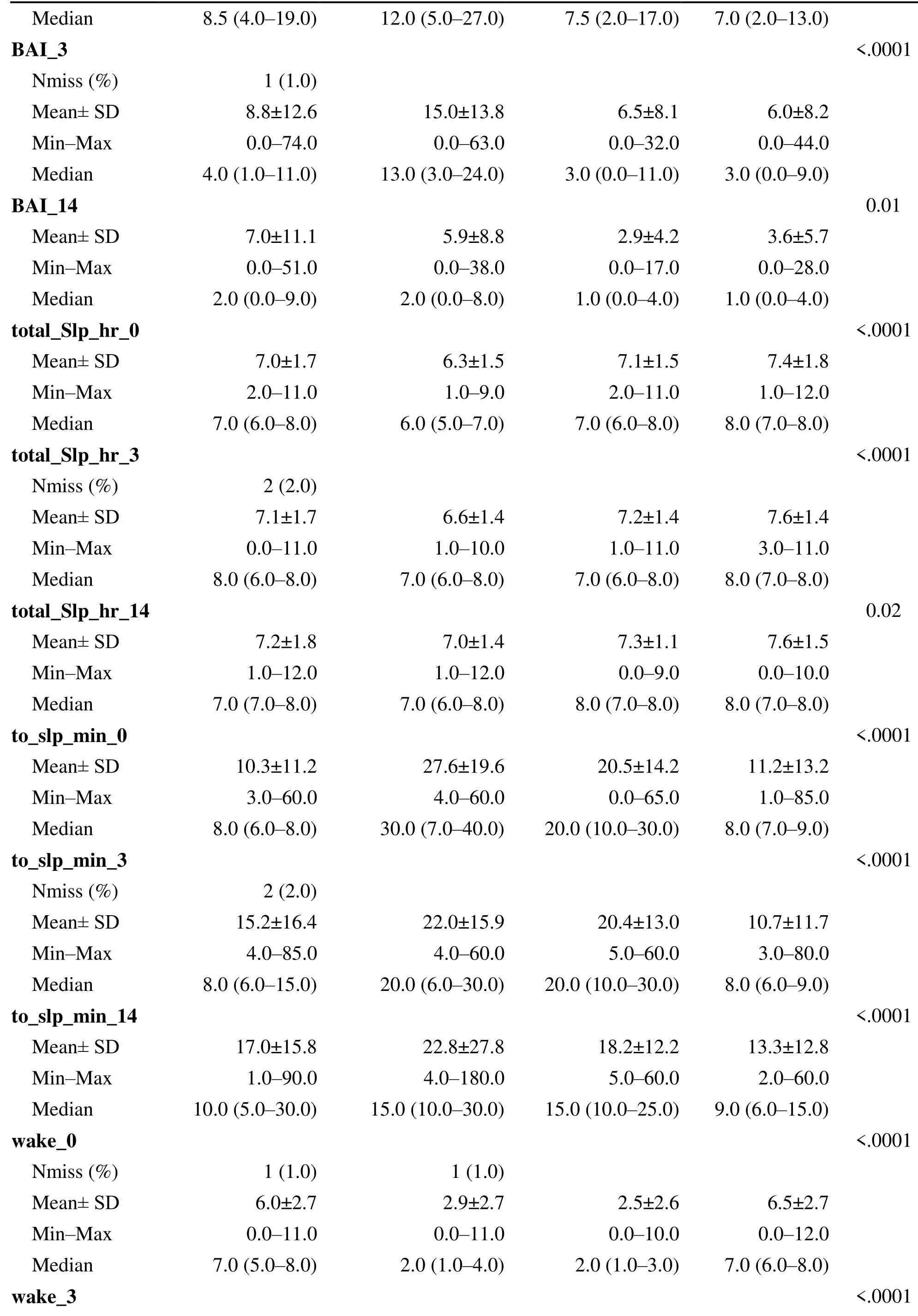

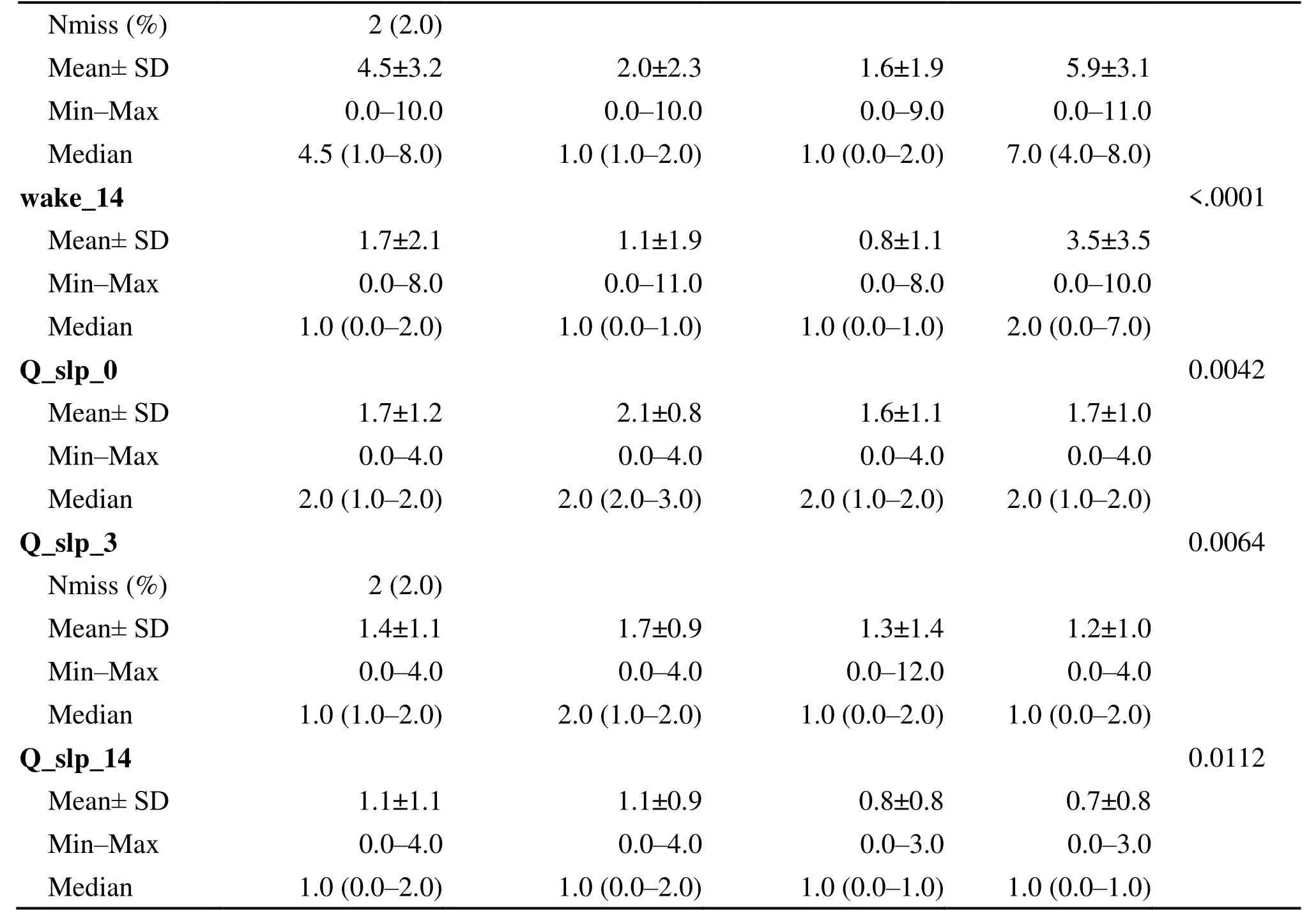

Secondary outcomes: continuous variables

Continuous outcome variables are summarized in Table 3.In within-group comparisons, striking reductions were observed in scores of HADS, PHQ-9, BAI, IESR, number of wakeups, and sleep quality scale at 3 days and 14 days compared to baseline (P≤ .0015) in each group.Total sleep hours per night were markedly greater at 14 days than baseline in both groups (P≤ .0046).Time to fall asleep was unchanged over the time in both groups.

In between-group comparisons, the AVNA group had significant reduction of HADS score at 3 days (P= .01) and 14 days (P= .02) compared to the UC group, with effect sizes of 0.217 and 0.218, respectively.BAI score of the AVNA group was also markedly lower than that of the UC group at 3 days (P= .03), with an effect size of 0.195.The AVNA group took much shorter time to fall asleep (P= .02) and rated their sleep quality being remarkably higher (P= .04) than the UC group at 14 days, with effect sizes of 0.214 and 0.234, respectively.

Adverse events

No adverse events were reported over the course of the study.

Discussion

This study for the first time applied self-administered AVNA to the management of emotional distress during the COVID-19 pandemic period.We revealed that selfadministered AVNA was superior to UC in improving distress-related symptoms.The AVNA group reported an approximately 10% higher response rate than the UC group, while the exacerbation rate was nearly 6-7% lower than that of the UC group across the two postbaseline measurement points.Self-administered AVNA produced significantly greater reduction in the mean scores of HADS after three days and 14 days of treatment and in the mean scores of BAI after three days of treatment.The greater reduction of PHQ scores of the AVNA group at 3 days also reached a margin at the statistical significance level.Furthermore, participants in the AVNA group spent much less time falling asleep and with better self-rated sleep quality than the UC group.No adverse events were reported between the two groups.These results indicate that the self-administered AVNA could rapidly relieve anxiousness and depressed mood and largely improved sleep disturbance.This situation of self-massage provides convenience for patients who cannot get medical assistance during isolation.

AVNA is easier to learn and practice independently than other non-drug measures recommended to alleviate anxiety and depression, such as body acupuncture,biofeedback therapy,meditation relaxation therapy, game therapy, art therapy, NaiKan therapy, Taiji therapy, yoga therapy and repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation, especially during city lockdown and social isolation caused by pandemics.

Although the positive effects of AVNA observed were small, with an average effect size of approximately 2.1, considering the rapid response, practicality, and safety, AVNA deserves to be recommended for patients with emotional distress under the current COVID-19 pandemic and other emergent events.In fact, auricular acupressure has been introduced to those who were experiencing mental distress in nursing students, cancer patients, women under in vitro fertilization and post-cesarean section [9-12].

Unlike conventional vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), in which a VNS device is embedded beneath the chest wall and the electrodes are implanted on the cervical vagal trunk via surgical procedure [23], transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulations (taVNS) is noninvasive, safer, and more practicable.In a nonrandomized clinical study [24] with 160 patients with major depressive disorders (MDD), the efficacy of taVNS was investigated by training the patients to apply bilateral taVNS at home.The intervention of taVNS was administered to the first cohort of patients(n=91) for 12 weeks.Patients (n=69) in the second cohort were offered sham taVNS for 4 weeks and then 8 weeks of real taVNS.Patients in the taVNS group had more reduction of the 24-item Hamilton Depression (HAMD) score than those of the sham taVNS group after the fourth week.The effect of the reduction of HAMD in both groups continued at the endpoint.Kong et al [14] found that compared with sham taVNS, taVNS treatment for one month can also alleviate anxiety, sleep disturbance and hopelessness in patients with MDD.The technique of taVNS has been growingly introduced into the treatment of neurological and psychiatric disorders, including epilepsy, pain, stroke, depression, insomnia, and dementia [8].ABVN mainly consists of thick-myelinated afferents that transmit mechanoreceptive sensations, such as touch, pressure, and movement, from the external ear to the brain [8, 25].The ABVN fibers and their terminals are distributed in the cavity of concha and the cymba concha with the highest density and in the surrounding areas with a related high density as shown in Figure 1 [7, 8].It is evidenced that the activation of thickmyelinated, afferent fibers of ABVN is essential to achieving the therapeutic efficacy of taVNS [26, 27].A large body of neuroimaging evidence confirms that taVNS broadly modulate a widespread brain network, including nucleus of the solitary tract, locus coeruleus, dorsal nucleus, parabrachial nucleus, hypothalamus, hippocampus, amygdala, cingulate and prefrontal cortex, all the brain regions that are directly or indirectly involved in the processing of emotional information and sleep/wake cycle [8].It thus appears that the anti-distress effects of AVNA observed in this study may be largely attributed to its broad modulation of the vagal brain network by activating mechanoreceptors via acupressure on ABVN-rich auricular areas.

Compared to traditional, in-person visit-required clinical trials, smartphone-based design could enhance the subject recruitment from all demographics, improve participants’ compliance with intervention, and diminish assessors’ bias.It hence offered a greater convenience with a time-saving course.Our experience that the completion of the entire study only took two months, with a negligible dropout rate reflects such advantages of smartphone-based clinical trial design.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be considered.First, the duration of AVNA intervention was somewhat short, with only 14 days.Further studies are warranted to evaluate the therapeutic value of long-term AVNA intervention.Second, it perhaps has a greater chance of causing large heterogeneity in intervention procedures and outcome measures due to the absence of onsite investigators’ guidance [28].This study that showed site differences in outcome variables echoed such weakness.In this study, trends of changes in outcome variables over time were consistent in the four sites.Site also served as a covariate included in the outcome analysis.Finally, due to the fact that participants were not blinded to their interventions, the influences of participant expectation on the outcomes appears not to be excluded.

Conclusion

During COVID-19 pandemic period, treatment with self-administrated AVNA was more effective than UC in reducing emotional distress of isolated populations.These findings support self-administered AVNA as a treatment option for patients with emotional distress under the COVID-19 pandemic or other emergent events.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the colleagues (including Changsong Liu, Jialun Zou) from Tsinghua University who developed this mini-program, Shuxin Wang from the First Hospital of Guangzhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine in Guangzhou, Hua Liu from Rehabilitation Hospital of Capital Medical University in Beijing, and Benjamin J.Cowling from Hongkong University for their suggestion for the design of the trial.Clinical data administration was performed by National Data Center of Traditional Chinese Medicine, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences.Jinling Zhang, Shaoyuan Li, Bin Zhao, Jiakai He, Dan Wang, Yifei Wang, Yue Zhang, Zixuan Zhang, Chuchu Xu, Enyu Zheng, Gege Chen, Lin Chen, Deqiang Gao, Ke Xu, Peilu Li, Qian Liu, Qianmei Xie, Sijing Du, Tao Zhang, Shuangshuang Fang, Xinyong Mao, Yajie Wang, Yu Cong, Yu Wang, Yue Jiao, Yurong Cui, Yuyan Pan, Zeng Cao, Zijing Tao, Zhi Wang collected the cases in Beijing, Limei Chen, Hao Wen, Jianhui Huang and Man Luo in Guangzhou, Bo Wang in Wuhan.We also would like to express our thanks to all of the patients who participated in this study.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary table 1.

Supplementary table 1.Primary and Secondary Outcomes from Baseline to the End Classified by 4 Sites

Variables Beijing (N=102) Guangzhou (N=102) Shenyang (N=100) Wuhan (N=102) P Value

Variables Beijing (N=102) Guangzhou (N=102) Shenyang (N=100) Wuhan (N=102) P Value

TMR Modern Herbal Medicine2021年2期

TMR Modern Herbal Medicine2021年2期

- TMR Modern Herbal Medicine的其它文章

- Application of artificial intelligence in tongue diagnosis of traditional Chinese medicine: A review

- A brief overview of traditional Chinese medicine prescription powered by artificial intelligence

- JSON-ASR: A lightweight data storage and exchange format for automatic systematic reviews of TCM

- Pathological tissue segmentation by using deep neural networks

- Artificial intelligence for the development and implementation guidelines for traditional Chinese medicine and integrated traditional Chinese and western medicine