阿尔多·凡·艾克的“间隙性”:从剩余空间到意义场所

和马町/Martijn de Geus

黄华青 译/Translated by HUANG Huaqing

1 序言

全球的城市发展皆容易产生出城市空隙——一类恰巧落在城市规划和建筑设计的缝隙之间的场所。这类空间包括:两栋楼宇之间的通道,高架路桥下方的空间,或是狭窄的、三角形的或是其他不规则形状的地块。鉴于它们这种显然“难以使用”的特征,我们通常将这类空间称作“城市空隙”。它们是剩余的、被忽略的、无价值的地块,没有任何潜力和特质。

这类空间真的毫无价值吗?

20 世纪中叶,阿尔多·凡·艾克竟能够将数百处像这样被忽视的空间转变为有意义的场所。基于对凡·艾克的阿姆斯特丹游乐场背后的设计进路的分析,本文试图从中凝练某种设计策略,进而对当代城市设计、规划和建筑实践有所启示。

凡·艾克的游乐场最初是建在临时的或是弃用的空地上。最初它们可被视为一种试图修正城市中游乐场地不均衡分布的应急措施,这些场地向所有市民开敞;但后来,这一项目的意义远远超出预期。这些看似简单的游乐场,其基地选择、设计和实施的背后所凝聚的设计策略,最终在荷兰各地的城市设计及更新设计中得到应用。借助极小化的干预措施,那些原本一直无人问津的空地,被赋予了城市生活中的积极角色。

因此,本文呼吁人们通过采取创造性的、以人为本的、场所营造的策略,重现碎片化的消极空间中极小却有意义的空间干预的重要价值。首先,文章回顾了这类空间的出现如何受到现代主义“功能城市”发展观念的影响,以及随后出现的城市规划和建筑设计学科的分离,对此凡·艾克一直持反叛态度。其次,我们将阿姆斯特丹游乐场作为凡·艾克的替代性场所营造策略的典型案例。最后,本文提供了将其设计策略转译于当代城市发展及建筑设计的参考框架:即理解凡·艾克的“间隙性”。这种间隙性可以理解为一种干预“之间的”空间的策略——无论从字面意义还是比喻意义而言——同时也是在此类未定义空间中促进城市中的人际交互的一种策略。简而言之,凡·艾克的间隙式策略可从4 个方面凝炼:开放性、间隙性、多中心性以及公众参与。它是一种为特定场所和境遇设计的策略,一种为创造更多可能而非占据空间的设计。

2 作为叛逆的人文主义者的凡·艾克

自从1947 年加入国际现代建筑协会(CIAM),凡·艾克就对时下流行的功能主义城市规划和建筑设计持有异常批判的态度,他本人在言行两方面皆致力于发展一种真正现代的、人性化的建筑。“由于没能创造性地管理城市,没能通过形态和细节设计来促进人性化,这已经导致了大多数新城的噩梦。”凡·艾克在1962 年如此写道,隐含指摘了现代主义城市规划的失败,这类规划在他看来是将“功能城市”的诉求放在了人性动机和欲求的前面。

凡·艾克加入国际现代建筑协会之时,该组织正处在勒·柯布西耶的领导下,以城市规划为先,为战后人口构想了一个由高层建筑塑造的未来。1931 年和1933 年的国际现代建筑协会大会持续倡导“功能城市”的理念,勒·柯布西耶紧接着发布“雅典宪章”,认为面对全球城市所遭遇的社会问题,最好的解决方式便是严格的功能分区,将人口分布至间隔宽远的高层公寓楼中。凡·艾克当时在阿姆斯特丹城市规划局工作的上司、也是时任国际现代建筑协会主席凡·伊斯特伦,已将这种理念贯彻在战后荷兰重建的宏伟工程中。他采取了一条自上而下的“整体”规划路径,以最高效率容纳“最大多数”。

重建和建造的需求非常巨大。然而,当凡·艾克加入规划部门之时,热情已然消退,不满之声四起,建设进展的衡量标准只是通过计算新建筑的数量、体量、大小等“客观事实”。凡·艾克刚从苏黎世联邦理工学院毕业的时候,他就曾加入抗议游行,要求减少压迫性环境。他的观点源于该时期苏黎世异常激进的社会环境。由于苏黎世在战争期间保持中立,它成为“被放逐或自我放逐的学者、科学家和先锋艺术家”的多重中心[1]。置身其中,凡·艾克发现当代艺术和科学的发展趋势尽管有所不同,但根本上都和他一样,正在“冲破理性主义的樊篱”。

还有像亨利·列斐伏尔这样的思想家,抨击了现代化进程给传统的、历史承续的城市肌理施予的压迫。列斐伏尔写道,他意识到20 世纪初正经历着前所未有的一种全新的、匿名的、贫瘠的、技术至上的空间类型的崛起。此外,在凡·艾克看来同样值得担忧的是,人居环境规划被粗暴地分割为两个学科——建筑设计和城市规划,这展现了那个时代的决定论特征,他并不认为有必要转变设计过程的机制。

在这一系列思潮转变的促使下,凡·艾克逐步发展出一套对抗现行标准的重要概念框架,通过他的写作和实践都有所表达。他的目标是将国际现代建筑协会的那种自上而下的、功能主义的城市设计路径,替代为一种“自下而上的”“接地气的”“情境式的”的设计策略[2]。凡·艾克试图发展一种建筑和城市的原创观点,一种真正当代的、人性化的建筑与城市理念,以对抗普遍流行的功能至上的规划方法——后者在他看来不仅割裂了现存城市,而且生产出异化的新城。针对国际建协式城市规划的第一个真正意义上的替代性、或至少说是补充性的方案,就是凡·艾克的阿姆斯特丹游乐场,“极小的、露天的构筑物,填补了拥挤城市中的间隙”[3]。

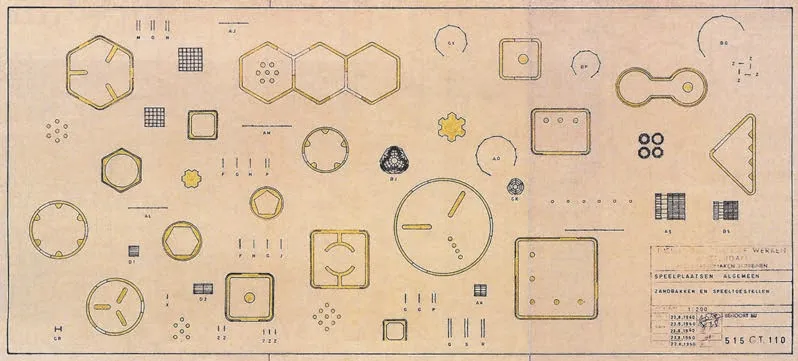

1947-1978 年间,阿尔多·凡·艾克设计并建造了阿姆斯特丹的数百处儿童游乐场,可以从图1这张地图中总览它们的位置分布。这些游乐场是临时性的、简单的,往往只在空地上进行最低限度的、最少的操作,只采用类似的基本设计元素,如图2所示。这样一种设计路径背后的理念是,通过临时性地占据这些场地,直至某个长时间的改造项目形成,为这些原本无人问津的场地赋予在城市生活中的积极角色。这种策略对于今天依然很有意义,正如恩尼亚和马泰拉[5]所写的那样,即便极小化干预对当今建筑学而言并不具有显著优势,但这类干预措施在今天的应用前景却比过去更广。他们提出,这类干预措施可跻身21 世纪最有启发的设计策略之列。对凡·艾克游乐场的干预及其设计手法背后设计策略和过程的理解,可以看作是正在进行的且关乎当代建筑角色与目标的一个重要转变。转变过程中,建筑作为城市领域中的极小干预途径,其作用越来越大。

3 作为整体性城市策略的凡·艾克游乐场

过去数十年间,建筑界对阿尔多·凡·艾克的游乐场的兴趣重燃,很多学者剖析了游乐场设计的不同层面、它们对城市肌理以及对儿童成长的影响。例如,勒费夫尔和德罗迪编辑出版了一本《游乐场与城市》的著作[4];永格尼尔、惠特哈根和萨尔在《环境心理学学刊》 发表的论文[6]、惠特哈根和卡尔乔在《心理学前沿》发表的论文[7]等,都从心理学视角讨论了凡·艾克游乐场中的“开放玩耍”理念、美学价值、经济性和创造性;所罗门[8]则讨论了玩耍本身的科学性,以及如何建造可以促进儿童成长的游乐场。此外,勒菲弗尔和多尔论述了如何将玩耍作为“自下而上城市”中的一种设计工具[9]。

如果对游乐场的具体设计和建筑方案感兴趣,我会推荐读者去阅读上面提到的文献。然而在这篇文章中,我们将阿姆斯特丹游乐场作为凡·艾克的替代性场所营造策略的案例,而非聚焦于游乐场设计本身,或是将游乐场作为一种城市空间类型。这一思考建立在勒费夫尔的观点之上,即这些游乐场的设计和开发背后的过程指向一种“彻底被忽视的城市设计工具,它能够很大程度上帮助提升那些在今天经常被疏离的内城街区中的社区空间”[10]。在此过程中,本文旨在通过理解凡·艾克的“间隙性”,为当代城市发展路径提供一个设计转译框架。

这种间隙性可以理解为一种面向城市空隙和剩余空间的设计策略,但凡·艾克的语言更适合被命名为一种为“之间的”空间的设计——无论从字面意义还是比喻意义而言。字面来看,它指向前文所提及的、因城市规划与建筑设计的分离而出现的空隙空间;而在比喻层面,凡·艾克也从这些特定场所之中看到了一种潜力,它可以成为激发城市中的人际互动的一种策略。这些空间介于家庭的私人领域以及城市的公共领域之间。下面我们将凡·艾克的间隙式策略拆解为4 个方面:开放性、间隙性、多中心性以及公众参与。这一切共同塑造了一套为场所和情境设计的策略,为更多可能而非占据空间而设计[11]。

3.1 开放性:从封闭的游乐园到开放的玩耍地

1 阿姆斯特丹736个游乐场位置示意,由阿尔多·凡·艾克在1947年至1978年间设计。地图为弗兰西斯·斯特卢瓦于1980年绘制/Location of 736 Amsterdam playgrounds designed by Aldo van Eyck between 1947 and 1978, map drawn up by Francis Strauven in 1980(图片来源/Source: 参考文献[13]/Ref [13])

2 凡·艾克的游乐场所使用的各种沙坑和游戏元素图录/Catalogue of various sandpits and play elements to be used in van eyck's playgrounds(图片来源/Source: 参考文献[3]/Ref[3])

1 Introduction

Urban development in cities around the world tends to produce urban voids, areas that fall between the cracks of the considered urban planning and subsequent architectural design.These spaces include corridors between two buildings, spaces underneath raised roads, junctions and overpasses; or narrow,triangular and otherwise irregularly shaped plots.Because of their apparent "un-usable" characteristics,we often refer to these as urban voids: leftover,neglected, worthless plots of land, devoid of potential and character.

Are they truly without value?

In the mid-20th century, Aldo van Eyck was able to turn hundreds of neglected spaces just like these into meaningful places.Analysing his design approach behind his Amsterdam Playgrounds, this text aims to distil a design strategy, that could be transposed to contemporary urban design, planning and architectural practice.

Van Eyck's playgrounds were initially built on temporary or unused plots of land.They could at first be seen as an emergency measure aimed to rectify the uneven distribution of play areas in the city, and these available to all its citizens, but they had a significance far beyond their original role.The design strategy behind the selection, design and execution of these simple playgrounds eventually became a strategy embedded in the design of urban design and regeneration all around the Netherlands.Through minimal interventions,an active role in city life was provided to places that otherwise would remain unused.

This text therefore should be seen as a plea for the importance and value of minimal, but meaningful interventions in these type of scattered negative spaces through creative, human-oriented, place making strategies.This text first provides an overview of how the appearance of these type of spaces resulted from the modernist "functional city" development ideology, and from its subsequent separation between the disciplines of urban planning and architectural design, which Van Eyck was rebelling against.Secondly, we take his Amsterdam Playgrounds as an example of van Eyck's alternative place making strategy, and thirdly, the text provides a framework for transposing his approach to contemporary urban development and architectural design: understanding Van Eyck's "Interstitiality".This interstitiality can be understood as a strategy regarding in-between spaces, literally and figuratively, as well as a strategy for these undefined spaces to encourage the interaction between people within the city.In short,Van Eyck's interstitial strategy can be characterised through four aspects: open-ness, interstitiality,polycentricity and citizen participation.It's a strategy of designing for place and occasion; designing for possibilities rather than for occupation.

2 Van Eyck as Humanist Rebel

Ever since joining the Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM) in 1947, van Eyck took an uncommonly critical attitude towards the prevailing functionalism in urban planning and architecture, and dedicated himself in word and deed to developing an authentically modern and humane architecture."Failure to govern multiplicity creatively, to humanize numbers by means of articulation and configuration, has led to the curse of most new towns", writes van Eyck in 1962,alluding to his conception of the failure of modernist town planning, that had in his eyes put "the functional city" ahead of human motives and desires.

Under Le Corbusier's leading, CIAM at the time of Van Eyck's joining prioritised urban planning envisioning a high rise future for a postwar population.Following CIAM meetings in 1931 and 1933 that called for a "Functional City",Le Corbusier had released the Athens Charter in which he described that the social problems faced by cities around the world could best be resolved by strict functional segregation, and by distributing the population into tall apartment blocks at widely spaced intervals.Van Eyck's boss at the Amsterdam Town Planning Department where van Eyck was working at that time, and CIAM Chairman at the time, Van Eesteren, had already integrated this approach in his colossal task of reconstructing the Netherlands after the war.He applied a top-down"total" planned approach to house "the largest number" most efficiently.

The drive to reconstruct and construct was massive.However, by the time that Van Eyck joined the Planning Department, enthusiasm had much waned and there were signs of discontent, given that progress was now measured by counting "objective facts" like number, volume, and size of new buildings.Fresh out of university, after having finished his studies at the ETH in Zurich, Van Eyck joined the growing protest in search of less oppressive environments.His opinions emerged out of the exceedingly stimulating environment of Zurich at that time.Zurich was a city that had been neutral during the war, and that had become a multilayered hub of "exiled or self-exiled intellectuals,scientists, avant-garde artists"[1].Amongst them, Van Eyck considered the trends in the contemporary arts and sciences and found that, despite their differences,what they had in common was that, like himself, they were "bursting the barriers of rationalism".

Others, like Henri Lefebvre, wrote about the pressures that were brought to bear upon traditional,historically inherited urban fabric in the process of this modernisation.Lefebvre wrote how he found that the early twentieth century saw an unprecedented rise of a new, anonymous, sterile, technocratic type of space.In addition, van Eyck was concerned how in his eyes the mere fact that habitat planning was arbitrarily split into two disciplines – architecture and urbanism– demonstrated the determinist quality of the times,which disregarded the necessity of transforming the mechanism of the design process.

Following in the wake of these changes, van Eyck developed over time a significant conceptual framework against the prevailing status quo, that was expressed both in writing and in practice.He aimed to turn the top-down, functional CIAM approach to urbanism into a "ground-up", "dirty real", "situational" approach[2].Van Eyck aimed to develop an original view of architecture and the city, a truly contemporary and human concept of architecture and urbanism in contrast to the prevailing technocratic planning that in his eyes tended to disintegrate existing cities while producing alienating new towns.The first real alternative, or at least complement, to this CIAM-style urban planning,was van Eyck's Amsterdam Playgrounds, "small roofless minimal structures occupying crowded interstitial urban voids"[3].

Between 1947 and 1978, Aldo van Eyck designed and built hundreds of children playgrounds in the city of Amsterdam[4], see the map in Fig.1 for an overview of their locations.These playgrounds were temporary and simple and involved only a few, minimum operations over vacant lots, with similar basic design elements,such as those found in Fig.2.The idea behind such an approach was sometimes to occupy these lots until a lasting transformation could be performed,and therefore providing an active role in city life was provided to places that otherwise would remain unused.This strategy remains relevant today, as Enia and Martella[5]write that even if minimal interventions are not a prerogative of present-day architecture, these interventions are implemented more often today than in the past.They argue that these interventions in fact can be placed among the most relevant design strategies of the 21st century.Understanding the design strategy and process behind van Eyck's playground interventions and its design ideology can be seen as part of this important, ongoing shift in design strategies, in which there is an increasing role for architecture as minimal interventions in the urban realm.

3 阿姆斯特丹会员制游乐公园,图为位于荷兰某街区的俱乐部/Amsterdam members-only play garden, image shows clubhouse at the fahrenheitstraat

4 阿姆斯特丹会员制游乐公园左侧,栅栏将游乐公园和俱乐部间隔开/Amsterdam members-only fenced off play garden with the clubhouse from figure 1 on the left(3.4图片来源/Sources: 参考文献[18]/Ref[18])

5 凡·艾克在CIAM第十次会议演讲时的几张幻灯片,杜布罗夫尼克,1956/Everal slides from van eyck's presentation at CIAM X, dubrovnic, 1956(图片来源/Source: 参考文献[13]/Ref[13])

尽管凡·艾克让阿姆斯特丹游乐场蜚声全球,但儿童室外玩耍场地的重要性在阿姆斯特丹早已得到公认,这延续了长期以来荷兰的一个传统,即将玩耍作为儿童城市生活的一部分。玩耍最初发生在城市的开放街道和广场,但随着城市发展,至19世纪末的阿姆斯特丹,关于儿童玩耍场地环境过差的怨声四起,这激发上流阶层在1880 年建造了城市中的第一处私人游乐场。随后,在荷兰掀起了一场关于儿童游乐公园的大规模运动,该运动的发起人是尤尔克·杨斯·克拉伦,他最初试图在自己居住的街区中建立一座游乐场,后来推动了一个游乐场共同体的成立。该组织成立于1917 年,名为“阿姆斯特丹游乐公园协会”;1937 年又发展为“阿姆斯特丹游乐公园集团”。请注意,这里使用的“游乐公园”(荷兰语“speeltuin”)一词是比通常使用的“游乐场”更准确的翻译。游乐公园指向一类后花园,它们藏在面向街道的俱乐部会所背后,有栏杆围合,由协会指派的管理员看管,只有协会会员的子女方可入内。由于家长必须是会员,且位置选择具有随机性,导致这些游乐公园在城市中的分布很散,且只能服务阿姆斯特丹极小部分的儿童群体,实质上“被认为是一个奢侈品”[12]。到了1940 年代,阿姆斯特丹已拥有一定程度的私人游乐场传统,这样的例子可参见图3、4。

真正为凡·艾克的介入铺平道路的,是1947年由雅科芭·穆尔德发起的一项运动——她是阿姆斯特丹城市规划局公共项目部的副手,这项运动试图修正游乐场的不均衡布局,让它们面向所有市民开放;除会员制的游乐花园之外,至少在每个街区设置一处“开放”游乐场。这些新建的游乐场将交由大众来监督管辖,此后也将由大众自下而上发起,这将在关于公众参与的第三部分阐明。这些新游乐场地的开放特质——没有围墙的游乐场,由周边社区松散地管理和监督——让它们得以成为一类“之间”的城市空间,可视为对介于私人的家和公共的城之间的一类城市领域的探索,凡·艾克将因此闻名。出于这样的动议,阿尔多·凡·艾克选择不再使用“游乐公园”(荷兰语speeltuin)一词,转而将这种游乐场地的新类型称作“游乐场”(荷兰语speelplaats),这在荷兰语中有极大的区别,隐含指向了凡·艾克的场所营造策略。

3.2 间隙性:激活缝隙中的城市剩余空间

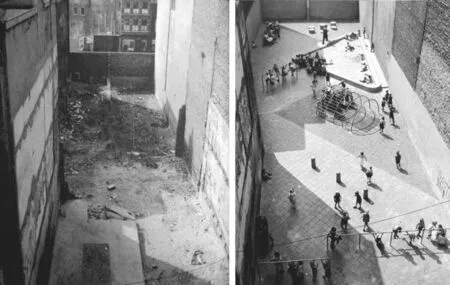

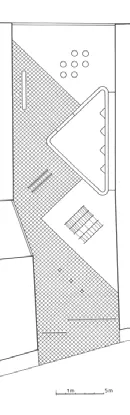

让这类新型游乐场地与众不同的第二个特征是,它们并不是在街区尺度自上而下设计的,而是自下而上的,是在人口致密的城市中发现的剩余的、间隙的空间尺度层面完成的。这在一定程度上是出于这样一个事实,即规划部门希望让每个街区都拥有属于自己的游乐场,故而经常有城市中心的空地被(临时地)改造为游乐场地。因此,游乐场不再只出现在光鲜的公园,或是制定的场地,也可出现在住宅楼之间、功能改变的停车场上,或是曾作为垃圾收集处的废弃场地。让凡·艾克自豪的是,他开启了一条更加“情境主义的”“自下而上”的城市设计路径,这条路径是对于在他看来功能城市规划已经失效的城市区域的回应。正如他1956 年在国际建协杜布罗夫尼克第十次会议中所指出的:“在由道路工程和拆除工人导致的不计其数的、无固定形状的孤岛上,在空闲的场地上,在比公共水景更适合儿童活动的场地上,我们迄今为止已在城市中找到了70 处这样的场地,用于建造游乐场”[13]。他在国际建协会议上播放的几页幻灯片,展示了其场所营造策略的几个早期案例,如图5、6 所示。不过,有一部分的剩余空间实际上并不是由失职的城市规划造成的,而是战争期间对阿姆斯特丹城市内外的轰炸所致,如图7-11 所示。无论这些空地的实际形成原因为何,这些由陈旧的墙体和残破的建筑所围合的场地,成为他的所有游乐场中最广为人知的案例[14]。实际上,这是一个颇具英雄主义色彩的社区故事,一处被轰炸或废弃的场地被赋予新生,成为一处公共游乐场。

3.3 参与性:地段考察的市民参与

如前所述,雅科芭·穆尔德——当时在科尼利斯·凡·伊斯特伦领导的阿姆斯特丹城市规划局工作——发起了开放式游乐场的动议,促使凡·艾克参与到贝特曼广场的第一个游乐场设计项目中。尽管最初它在一定程度上被作为一项修正游乐公园的不均衡布局的策略,并且促进游乐场所向所有市民开放,但它同时也是公众参与的产物,尤其是参与到为这类干预措施寻找合适场地的调研中。穆尔德率先在她自己居住的街区中找到了一个可能的场地,因为她早已注意到街区中的孩子无处可玩耍。在她那位26 岁的助手阿尔多·凡·艾克建成这座游乐场大约一个月之后,一位住在几个街区之外的女性看到这处新的游乐场所,她于是写信给公共项目部,请求在她的街区也建造一处。自此,游乐场就如星火燎原,最初是在历史城市中心,后来从1950 年代开始,逐步蔓延到城市西部的新区[10]。

6 道路交叉口旁剩余三角形游乐场平面/Plan situation drawing of playground on leftover triangular space next to road intersection(图片来源/Source: 阿姆斯特丹凡·艾克城市档案馆线上文件/Aldo van Eyck Archive in the Amsterdam City Archive, sourced online via http://www.play-scapes.com/playhistory/mid-century-modern/aldo-van-eycks-playgroundplans/)

3 Understanding van Eyck's Playgrounds as Integral Urban Strategy

Over the last decades, there is a renewed interest in the playgrounds of Aldo van Eyck, with many scholars dissecting different aspects of their designs, the effect they have on the city fabric, and on the development of children.For instance, Lefaivre and de Roode[4]who edited a publication regarding "the playgrounds and the city", Jongeneel, Withagen and Zaal[6]in the

Journal of Environmental Psychology and Withagen and Caljouw[7]in Frontiers of Psychology, both from a psychological point of view, regarding aspects of"open play", aesthetics, affordances, and creativity of his playgrounds, or Solomon[8]regarding the science of play itself and how to build playgrounds that enhance children's development.In addition, Lefaivre and Döll[9]focused on how to consider play as a design tool in a"Ground Up City".

For those interested in the particular design and architectural solutions of these playgrounds,I would recommend to read up on the sources mentioned here.For this text though, we understand the Amsterdam playgrounds as an example of van Eyck's alternative place making strategy, rather than focussing on the design of the playgrounds themselves, or the relevance that playgrounds as a typology have in cities.This builds on Lefaivre's suggestion that the process behind the design and development of these playgrounds yield a potent "totally ignored, urban design tool that has great relevance for the enhancement of community in the often alienated inner-city neighbourhoods of today"[10].In doing so, the text aims to provide a framework for transposing van Eyck's approach to contemporary urban development, through understanding van Eyck's "Interstitiality".

This interstitiality can be understood as a strategy regarding urban voids and leftover spaces, but in Van Eyck's own terms would more appropriately be named as designing for in-between spaces, literally and figuratively.Literally, this refers to void spaces that arise as a result of the separation between urban planning and architectural design,as mentioned earlier, but figuratively, Van Eyck also saw potential in these particular places as a strategy to encourage the interaction between people within the city.Places in between the private realm of the home, and the collective realm of the city.In the following section, we break down van Eyck's interstitial strategy through four aspects:open-ness, interstitiality, polycentricity and citizen participation.All together enabling a strategy of designing for place and occasion, designing for possibilities rather than for occupation[11].

3.1 Openness: From Closed Play Gardens to Open Play Places

Though van Eyck made Amsterdam's playgrounds famous around the world, the importance of areas for children to play outdoors in the city was already well established, and followed in a long Dutch tradition of celebrating play as a part of the urban life of children.Originally occurring in the open streets and plazas of cities, through increasing urban development, many complaints arose regarding poor playing conditions for children in Amsterdam at the end of the 19th Century,sparking upper-class citizens to create the first private playground in the city in 1880.A larger movement in the Netherlands regarding play gardens subsequently formed, an initiative founded by Uilke Jans Klaren,as his efforts in creating a playground in his own neighbourhood, eventually gave rise to establishing a playground collective.Founded in 1917, it was called the "Bond van Amsterdamse Speeltuinverenigingen"(Bond of Amsterdam Play Garden Associations), from which in 1937 the "the Amsterdams Speeltuinen Verbond" (Amsterdam Cooperation for Play Gardens)was formed.Please note how the word "play gardens" (from the Dutch word "speeltuin") is a more accurate translation than the commonly used word"playground".These play gardens resembled backyard gardens, behind street-facing clubhouses, and were fenced plots supervised by keepers belonging to the association, and exclusively accessible for the children of the association's members.The fact that you had to be a member, combined with their arbitrary placement,making them placed scattered around the city, made that these play gardens only served a limited segment of Amsterdam's children's population, and were indeed"considered a luxury"[12].By the 1940s, Amsterdam had a considerable tradition of such private playgrounds, an example can be seen in Fig.3, 4.

What paved the way for van Eyck's involvement was a move in 1947 by Jakoba Mulder, second in charge of the Public Works Department at the Amsterdam Town Planning Department, to rectify this uneven distribution and to make play areas available to all its citizens, by installing at least one "open" playground in every neighbourhood, in addition to the members-only play gardens.These new playgrounds would be entrusted to the supervision of the general public, and would later also be initiated bottom-up by the general public, as will be explained in Point 3 regarding citizen participation.The open character of these new play areas, in which a non-fenced play area would be loosely governed and supervised by the surrounding community, made it possible for the playground to work as the type of urban in-between space that van Eyck was to become known for, as the exploration of an urban realm that would fit between the private realm of the home and the collective realm of the city.For this initiative Aldo van Eyck also chose not to continue to use the name"play garden" (Dutch: speeltuin), but instead described these new types of playgrounds as "play places" (Dutch:speelplaats), in Dutch a significant difference, alluding to van Eyck's strategy of place making.

3.2 Interstitiality: Regenerating Interstitial Urban Leftover Spaces

A second aspect that made these new play places so different, was that they were not conceived topdown on the scale of the neighbourhood or block,but bottom-up, on the scale of left-over, interstitial spaces that were found inside the densely populated city.This was partially due to the fact that the department wanted to give every neighbourhood its own playground, so they often turned vacant lots in the city centre into (temporary) play areas.As such, they did not just appear in fancy parks, or in designated play areas, but also in between housing blocks, on converted parking lots, and abandoned derelict plots previously used as garbage dumps.Van Eyck was proud to have started a more "situationist", "ground up" approach to urban design as a statement to those areas where he thought the functional city planning was failing, as he reported to the CIAM X meeting in Dubrovnik in 1956 that: "on innumerable formless islands left over by the road engineer and demolition worker, on empty plots,on places better suited to the child than the public watering place, 70 places have been identified in this city so far for the making of play places"[13].Several slides of his CIAM presentation showing the earliest examples of his space place making strategy can be seen in Fig.5, 6.However, some of these leftover spaces were in fact not caused by bad urban planning, but were in fact war-torn, bomb damaged sites in and around Amsterdam, as seen in Fig.7-11.Regardless of the exact reason behind their voidness, hemmed in by old walls and ramshackle buildings, these have come to be the best known amongst all his playgrounds[14].Indeed,it was quite the heroic community story, a bombed or abandoned lot, that was induced with new life as a public play area.

3.3 Participation: Citizen Participation in Location Scouting

7 置入建筑夹缝间的游乐场前后,迪克斯特勒特,1954/Before and after view of playground inserted into empty plot between buildings at dijkstraat, 1954(图片来源/Source:阿姆斯特丹凡·艾克城市档案馆线上文件/Aldo van eyck archive in the amsterdam city archive, https://www.archined.nl/2002/06/de-speelplaatsen-van-aldo-van-eyck/)

8 迪克斯特勒特游乐场平面/Plan drawing of playground at dijkstraat, as shown in figure 7(图片来源/Source: 3https://i2.wp.com/artbooks.yupnet.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2015/01/Picture-13.png)

9 游乐场置入被战争轰炸的弃置空间前后,泽迪克,1955/Before and after view of playground inserted into war bombed derelict plot at zeedijk, 1955

就这样,每座游乐场并不来自任何城市规划的既定任务,而是源自当地社区直接而具体的需求。阿姆斯特丹会将游乐场植入每一处其市民认为有必要的地方。如莉安娜·勒费夫尔所言,凡·艾克曾推荐她去重访市政档案馆,“档案馆中藏有190 封市民信件,都是手写的;如果某些信件的字迹难以辨识,公共项目部会将其转译为职业化的打印体,便于相关公务员阅读。”通过一个高度系统化的流程,每封寄往公共项目部的信件都会导向一系列给寄信者本人的复函、过程备忘录、设计草图和平面、立场报告以及政策提案。每一个游乐场都是定制的产物,是对一个或一群特定市民的某个特定需求的回应,是对某个被认为具有建造游乐场潜质的特定场地的回应。这样一种将市民纳入此般尺度的自下而上城市更新之中的系统化组织,代表了一个在城市层面的参与性政治及民主行动的独有案例,形成了一份“15m 长的档案”[10]。

据勒费夫尔所言[2],随着这一进程的成功,凡·伊斯特伦“尽管并未放弃自上而下的规划理念”,但也开始“学习”这些在现存城市肌理中剩余的、间隙的场所的独特性和异规性,并试着在工作中纳入、而非无视它们。

3.4 多中心性:创造场所的网络

凡·艾克的间隙性策略的最后一个层次,也不是一开始便计划好的,而是源于借助高效而有效的设计策略管理项目选址的严谨过程。鉴于这类开放游乐场地的间隙性和广阔分布的特质,游乐场成了一个多中心网络。它几乎独自形成了一个城市片层,充满童真,持续变化又可变,整齐地编织在功能城市的粗放肌理之中。

1947 年,这个项目刚刚开启时,城市中只有不到30 处游乐公园,这一数字自从1929 年以来并未增长;随着凡·伊斯特伦在城市规划局走马上任,他下令绘制了一系列城市地图,详细编目城市(公共)设施的供给和分布。从这些地图中,可以令人震惊地看到,虽然儿童游乐场已是凡·伊斯特伦关心的五大主要事业之一,但当时的阿姆斯特丹几乎没有什么服务儿童的此类设施。到了1968 年,这种情况大为改观。阿姆斯特丹已经拥有超过1000座游乐场,这就意味着,从1947 年开始,平均每年就要设计并建造不少于50 座游乐场[10]。每座游乐场都是由凡·伊斯特伦和他的助手雅科芭·穆尔德亲自过问,由阿尔多·凡·艾克设计。经过逾20年的建造,战后的阿姆斯特丹游乐场成了一个值得铭记的成功故事,它创造了一张多中心的、扎根社区的游乐场之网。它如同一片游乐场的星云,嵌入至该时期在城市中成长起来的儿童的集体记忆中。而在此后的整个荷兰,由于凡·艾克在游乐场中使用的设计工具以及这种自下而上的、间隙式的设计策略都极具影响力,它们也在其他城市的市政项目部门得到广泛复制。

凡·艾克的游乐场除了对阿姆斯特丹以及荷兰其它地区的社会生活产生影响之外,也对建筑学和城市设计学科的发展具有深远意义。它推动了建筑学的多项重要进展——“社区”和“对话”的建筑,人性的建筑,“之间的领域”的形式塑造等,以作为对于国际建协抽象的功能主义规划的替代选择。由此勒费夫尔认为,它们不仅是游乐场设计的新类型,更代表了二战后面向公共空间和城市设计的一条新路径[10]。

4 走向功能城市中的间隙性

顺着这一游乐场网络的自下而上的有机过程,凡·伊斯特伦将前面提到的那些在阿姆斯特丹传统城市肌理中涌现的特征,整合到他在西阿姆斯特丹战后新建街区的设计策略中:包括斯劳特戴克、斯洛特梅尔、格兹维尔德。凡·艾克的游乐场策略也不再仅用于填充历史城市中心的空隙场地,而应用到更多经过功能主义规划的新城之中。事实上,游乐场成为了凡·伊斯特伦西阿姆斯特丹新城镇政策的一个组成部分,在首先测试游乐场的社区中,人们目睹了这些变化,亦是人们对生活质量改善的认可。

此外,在新城规划政策中落实的不仅是空间效果。不同于在其早期设计中采取的纯粹功能主义的、效率优先的、自上而下的公共服务设施规划和分布,在凡·伊斯特伦的档案记录中,他不仅宣称自己将游乐场作为斯洛特梅尔规划设计的重要部分,而且还特别提到,游乐场必须是“从使用者层面要求的对象”;到那个时候,新城中每个提出需求的街区都会得到一座游乐场。这不仅让我们理解了设施和空间本身的重要性,还应认识到恰当的选址以及公众参与的重要性。由此,它结合了游乐场的开放性、它的间隙式布局策略、它的公众参与设计策略,并最终导向了一个间隙性游乐空间的多中心网络。

As mentioned, Jacoba Mulder, who worked under Cornelis van Eesteren at the Amsterdam Town Planning Department, initiated the open playground initiative, leading to van Eyck's first playground design for the Bertelmanplein.Though it was in part meant as a strategy to rectify the uneven distribution of play gardens, and to make play areas available to all its citizens, it was simultaneously a result of citizen participation in the scouting of appropriate locations for these interventions.Mulder herself was the first to start to identify a possible location in her neighbourhood, as she had noticed that the children in her neighbourhood had nowhere to play.A month or so after her 26-year old assistant Aldo van Eyck had completed the playground, a woman living a few blocks away saw the new play space and wrote to the Public Works department requesting one for her area.From that moment on, they spread like wildfire, first through the historical centre, then, in the course of the 1950s,to the new districts to the west of the city[10].

As such, each playground was not conceived within a master plan assignment, but rather resulted from a direct and specific need and request of a local community.The city embedded playgrounds where the people of Amsterdam felt they should be placed.As Liane Lefaivre reports, after van Eyck recommended her to go revisit the municipal archives, "The archive holds 190 letters by citizens.All were written by hand.And when the letter was difficult to read, the public works department had them typed out professionally, so that the relevant civil servants could read them".In a very systematic process, each letter sent to the departments lead to the production of return correspondence with the initial sender, internal memos, of drawings and plans, of position papers and of policy proposals.Each one was made to order, in response to a specific request by a specific citizen or group of citizens for a specific site that had been identified as the potential location for a playground.This systematic organisation of citizen participation in bottom-up urban regeneration at this scale represents a unique example of participatory politics and democracy in action at the urban level,making up a "fifteen – metre long archive"[10].

Following the success of this process, according to Lefaivre[2], van Eesteren, "without abandoning the idea of top-down planning", began to "learn" from the particularities and irregularities of these left-over,interstitial places in the existing fabric of the city and to work with them rather than to overlook them.

3.4 Polycentricity: Creating a Network of Places

The last aspect of van Eyck's interstitial strategy was again not so much an initially planned effort, but a result of the rigorous process of managing location scouting through efficient and effective design strategies.Because of the interstitial and wide-spread nature of the open play places, the playgrounds became part of a polycentric network.It almost became its own layer in the city, playful, continually changing and changeable, which was neatly intertwined in the rough fabric of the functional city.

In 1947, at the start of this process, there were fewer than 30 play gardens in the city, which had not increased from 1929, when van Eesteren, the erstwhile new director of the Municipal Department of Public Works, commissioned a series of city maps that took inventory of the availability and distribution of (public)services.From these maps it's striking to see that even though playgrounds for children were already one of the five main concerns of van Eesteren, there were hardly any services for children available at that time yet.By 1968, the situation was radically different.Amsterdam now had over 1000 playgrounds, which means no fewer than 50 playgrounds were designed and produced every year from 1947 onward[10].Each playground was individually dealt with by van Eesteren and his associate Jacoba Mulder, each was designed by Aldo van Eyck.Built up over a period of just over 20 years, the postwar Amsterdam playgrounds were a remarkable success story that created a polycentric network of community based play areas.A galaxy of playgrounds, that embedded the playground into the collective memory of children growing up in the city at that time.The network of places went further than just Amsterdam, and had a strong influence in the Netherlands at large from there on, as both the Van Eyck-designed equipment of his Amsterdam playgrounds as well as their bottom-up,interstitial design strategy were widely copied in other municipalities and public works departments.

Besides the impact that van Eyck's playgrounds had on the social life in Amsterdam, and the rest of the Netherlands, they were also of great significance for the development of the discipline of architecture and urban design.It was here that the major breakthroughs of an architecture of "community" and "dialogue" and of the human and formal building of the "realm of the inbetween" as an alternative to CIAM functional abstract planning took place.As such, Lefaivre[10]argues that they were the first examples not only of a new type of playground design, but also, in general, of a new, post-WWII approach to public space and urban design.

4 Towards Interstitiality Within the Functional City

Following the bottom-up, organic process of this emerging network of playgrounds, van Eesteren took the above-mentioned features that had initially emerged ad-hoc in the traditional fabric of Amsterdam and incorporated them as design strategy in his designs for new post-war neighbourhoods of West-Amsterdam: in Sloterdijk, Slotermeer and Geuzeveld.Van Eyck's playground strategies were thus no longer limited to infill sites in the historic city centre, but spread into the functionally planned new towns.The fact that the playgrounds became an integral part of van Eesteren's policy for the new towns of West Amsterdam can be regarded as an acknowledgement of the improvement in quality of life that was witnessed in the neighbourhoods where they had been tested first.

In addition, it was not merely the spatial effect that was implemented in the new town policy.As, unlike Van Eesteren's earlier approach to a purely functional,efficient top-down planning and distribution of public services, there is a memo in the van Eesteren archive in which he not only declares that he is making the playgrounds an integral part of his design for Slotermeer, but specifying that they must be "the object of request on the part of the users", and by that time every block in the new towns that wanted a playground was granted one[10].Herewith not only understanding the importance of the service and space itself, but also the process of the right location and citizen participation.It thus integrated the open-ness of the playgrounds, with its interstitial distribution strategy,and citizen participation as a design strategy that leads to a polycentric network of interstitial play spaces.

For van Eyck the playground design became a manifestation of both architectural and intellectual observations.They provided a strategy for dealing with what he felt were the flaws of top-down modernist town planning, while at the same time enabling explorations into a new type of architecture.One that was not about defining boundaries, and enclosed spaces, but one that was about making places and allowing occasions to occur.A strategy that designed for possibilities rather than for occupation."Space in the image of man is place,and time in the image of man is occasion.Split apart by the schizophrenic mechanism of deterministic one-track thinking, time and space remain frozen abstractions…Place and occasion constitute each other's realisation in human terms: since man is both the subject and object of architecture, it follows that its primary job is to provide the former for the sake of the latter.Since,furthermore, place and occasion imply participation in what exists, lack of place - and thus lack of occasion –will cause loss of identity, isolation and frustration"[11].

10 泽迪克游乐场照片/Colour photo for playground at zeedijk(图片来源/Source: 凡·艾克基金会线上文件/Van Eyck Foundation, http://vaneyckfoundation.nl/2018/11/23/theamsterdam-playgrounds-1947-78/)

12 由凡·艾克和博世设计的新五角楼,1983/Het pentagon -nieuwmarkt by van eyck and bosch, 1983(图片来源/Source: 荷兰建筑学会/NAI, Netherlands Architecture Institute, http://schatkamer.nai.nl/nl/projecten/woningbouwcomplex-sint-antoniesbreestraat-pentagon)

11 泽迪克游乐场平面/Plan for playground at zeedijk of figure 9(图片来源/Source: 阿姆斯特丹凡·艾克城市档案馆线上文件/Aldo van Eyck Archive in the Amsterdam City Archive,https://www.archined.nl/2002/06/de-speelplaatsen-vanaldo-van-eyck/)

13 由凡·艾克和博世设计的城市立面填充项目/Urban infill project, hubertushuis by van eyck and bosch, 1984(图片来源/Source: 凡·艾克基金会线上文件/Van Eyck Foundation,http://vaneyckfoundation.nl/2018/11/21/hubertushuisamsterdam/)

对于凡·艾克而言,游乐场设计成了他的建筑学及智识观察的体现。它们提供了一种策略来应对他眼中自上而下的现代主义城市规划的缺陷,同时促进一类新建筑类型的探索。这类建筑并不关于限定边界或围合空间,而是关乎塑造场所,让不同的情境在此发生。这是一个为了创造可能而非占据空间的策略。“在人的映射下,空间成为地方,时间成为境遇。由于被确定性的单轨思维的精神分裂机制所撕裂,时间和空间一直是冰封的抽象物……场所和境遇在人的意义层面是相互成就的:因为人同时是建筑的主体和客体,这就意味着,建筑的主要职责就是为了境遇而提供场所。此外,场所和境遇意味着参与其中,而缺乏场所感——由此也缺乏境遇感——将会导致身份感的丧失,导致孤立和沮丧”[11]。

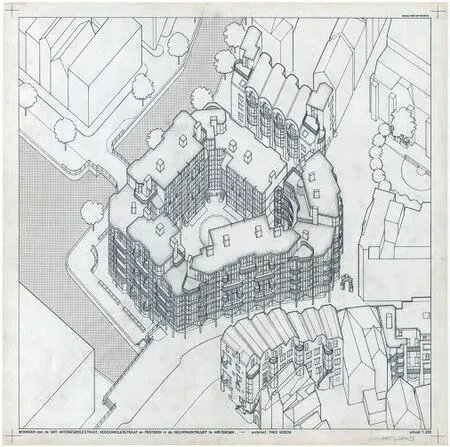

这样一种间隙式的设计策略,结合城市认同以及场所营造的理念,对荷兰的城市发展、以及凡·艾克之后的建筑师都具有持续性的影响。阿尔多·凡·艾克的“结构主义”建筑哲学启发了包括尤普·凡·斯蒂格特、赫曼·赫兹伯格在内的建筑师。最终,推动了一种全新的城市发展模型的出现——“为社区的设计”——用城市社区中小规模的参与式项目,取代大规模的现代主义式干预。其中最早的、也是最具代表性的项目之一,是阿姆斯特丹新市场区域的再开发,由蒂奥·博世和阿尔多·凡·艾克设计。在这个项目中,凡·艾克关于间隙空间、无等级式构成和参与式设计的理念,导向了一种可以轻松融入街区现存肌理的建筑。这座建筑被称作“五角楼”,得名于它的5 条城市界面,是一个更接近建筑尺度的城市改造项目。它填充了一块开放场地,可以反过来回馈城市以居住、商店、办公和小商业等功能空间(图12)。另一个应用了凡·艾克的间隙式设计策略的典型案例,是图13 所示的建筑项目,这个项目是阿姆斯特丹的胡贝图斯社区的“母亲住宅”。该项目位于一块城市空隙场地,地段上原有一座犹太教堂和学校,但在二战后被弃用了。项目于1983 年建成,它填充了一处19 世纪街道立面的缝隙,因此需要在建筑高度、垂直布局以及基础结构上契合现存的立面墙体;但它显然也因其大胆的用色以及所谓采光井和交通“枢纽”的设计而易于辨识,它成了一处在街道侧和内部花园之间充满亲和力的间隙空间。凡·艾克的加建也帮助整合并翻修了两旁现存的历史建筑。

5 结论:以极小干预重估城市空隙

正如我们在文章开头提到的,在凡·艾克看来,现代城市的“科学规划过程”直接导致了他在当代城市中发现的问题,例如身份缺失、职住分离、城市设计过程的整体产业化等。凡·艾克并未顺从这些潮流,而是认为建筑师应对此保持批判,由此开启了对城市本质的反思,在其中首要考量“城市究竟要为人性的动机和欲望提供什么”[11]。

从这一视角出发,本文在开头讨论了城市剩余空间的价值缺失——无论是现代城市开发的直接后果还是其他原因导致,进而呈现了阿尔多·凡·艾克将数百处被忽视的剩余空间转变为意义场所的过程。基于对凡·艾克在阿姆斯特丹游乐场背后的设计策略的分析,本文展示了从数百个面向同一设计问题的反复实践中,如何生发出一种独特的设计策略——将间隙性与公共参与、开放性相融合,以建立一张多中心的社区场所网络。

尽管凡·艾克的游乐场最初是建在临时的、弃用的空地上,但它的意义却远远超出了最初的定位,它是一个应对时代需求的创造性城市解决方案,并最终成为一种在荷兰各地的新城区域设计中广泛应用的设计策略。这后来进一步发展为一种广泛意义上的城市设计、规划和建筑实践路径,尤其与城市更新及复兴相关,也对荷兰的城市发展实践产生了深远影响。此外,凡·艾克还引入了很多我们如今习以为常的建筑思想观念,如身份、之间、互惠、场所和境遇等,它超越了功能城市,打开了面向建成环境潜在特质的全新的结构化视角。

放在当代建筑实践的视野下,我们可以看到,对于城市空隙体系的认知正在发生类似的变化。根据金建佑[15]的说法,当代城市是一个过度膨胀的有机体,它需要消减而非增加元素。无论其现存状态和空间品质如何,城市空隙都在城市作为一个整体的平衡和稳定层面扮演着重要角色。在过去一个世纪,这些空隙主要被视为可建造的场所。如今,它们往往被作为城市的构成要素,就因为它们的空白而发挥着特定的功用。从本文的分析中不难看到,借助极小的干预,那些原本可能闲置的场地就可以被赋予在城市生活中的积极作用。

总结而言,凡·艾克的设计策略是关于节制的,关于少做的,关于回馈的。它是一种为场所和境遇设计的策略,一种创造可能而非简单占据的策略。这样一种“几乎什么也不做”的策略,可从多方面来解释。在恩尼亚和马泰拉[5]看来,它可以意味着对不积极的偏好,因此根本无需对场地做任何改变;或是设计一个临时性项目,只在一段有限的时间内占据空间;或是采取某种极其微小却是永久性的干预手段。根据所处的境况,这样一条路径有利于保护场所,有利于找回或重新激活场所中的潜在品质。这种策略不仅可以应用于某个特定场所的单一干预,也可以体现在多个不同场所共同作用的系列工程之中。

通过理解凡·艾克的间隙式设计策略的过程和成效,笔者希望本文的发现能够呼吁人们采取创造性的、以人为本的、场所营造的策略,以重新凸显碎片化的剩余空间中极小却有意义的干预手段的重要价值。□

This strategy of interstitial design, combined with the notion of urban identity and place making had a lasting effect on urban development in the Netherlands, and on generations of architects following van Eyck.The "structuralist" architectural philosophy of Aldo van Eyck inspired architects such as Joop van Stigt and Herman Hertzberger.And eventually, a whole new model for urban development emerged – "bouwen voor de buurt"(building for the neighbourhood) – that was to replace large-scale modernist interventions with small scale participative projects in urban neighbourhoods.One of the first and most symbolic of these projects was the redevelopment of the Nieuwmarkt in Amsterdam,by Theo Bosch and Aldo van Eyck.Here, van Eyck's ideas on interstitial space, non-hierarchical composition,and participatory planning led to an architecture that could easily mold into the existing tissue of the neighbourhood.Known as the Pentagon, named after the five-sides of the plot facing the city, the project is an urban intervention of a more architectural scale,that filled in an open area, and could give something back to the city by combining residential, shops, office space and small businesses, see Fig.12.Another great example of van Eyck's interstitial strategy applied in later architectural practices can be seen in Fig.13, in his project for the Mothers' House for the Hubertus Society, also in Amsterdam.The project was located at the urban void site of a former synagogue and school that had become dilapidated and out of use following WWII.The project, completed in 1983, comprised the infilling of a gap in the nineteenth-century street façade, and as such conforms to the existing façade wall as regards building height, vertical layout and understructure, but is also clearly distinguished by the striking use of colour, and the so-called light well and circulation "joint", executed as an inviting in-between space between the street side and the inner garden.Van Eyck's new infill also worked to integrate and renovate the two existing adjacent historic buildings

5 Conclusion: Reappraising the Urban Void Through Minimal Intervention

As we noted at the beginning of the article, for van Eyck the "scientific planning process" of modern cities directly lead to the problems that he observed in contemporary cities, such as a loss of human identity, segregation of work and dwelling, and the industrialisation of the urban design process in general.Instead of complying with these trends, he felt that architects should be critical towards them and he started a reflection on the nature of the city that considered foremost "what a city really has to provide for in terms of human motives and desires"[11].

From this perspective, the text started with questioning the value of urban leftover spaces,whether a direct result of modern urban development or otherwise, and described a process through which Aldo van Eyck was able to turn hundreds of neglected leftover spaces into meaningful places.By way of analysing van Eyck's design approach behind the Amsterdam Playgrounds, this text has shown how from a series of hundreds of iterations of the same design problem, a distinct design strategy arose, that combined interstitiality with citizen participation and open-ness to establish a polycentric network of community places.

Though van Eyck's playgrounds were initially built on temporary or unused plots of land, they had a significance far beyond their original role as a creative urban solution in a time of need, and eventually became a strategy embedded in the design of new towns and urban areas all around the Netherlands.This later evolved further into a general approach to urban design,planning and architectural practices, especially related to urban renewal and regeneration, that heavily influenced the general practice of urban development in the Netherlands.In addition, van Eyck eventually introduced many new notions into architectural thinking that we take for granted today, such as identity, the in-between,reciprocity, and place and occasion, opening up new structural insights into the potential qualities of the built environment, beyond the functional city.

Transposed to contemporary practice, we find that the perception of the system of urban voids is also undergoing a similar change.According to Kim Gunwoo[15]contemporary cities are hypertrophic organisms that require elimination rather than the addition of elements.Regardless of their condition and spatial quality, urban voids currently play an important role in balancing and stabilising the city as a whole.In the last century, these voids were mainly regarded as places to build.Today, these voids are often treated as constitutive elements of the city and essential for precise functioning because they are empty.From our analysis, we have indeed seen how through minimal interventions, an active role in city life can be provided to places that otherwise would remain unused.

Altogether, Van Eyck's design strategy has been one of restraint.Of doing less, of giving back.It's a strategy of designing for place and occasion; designing for possibilities rather than for occupation.This strategy of "almost doing nothing" can be explained in many ways.According to Enia and Martella[5]it can mean opting for inaction and thus not modifying a place at all; or designing a temporary project intended to occupy it only for a limited period of time; or also carrying out a particularly small but permanent intervention.Depending on the circumstances, it is an approach that could help to protect a place, to reclaim it or to reactivate certain latent qualities.This strategy can be implemented both through a single intervention on a specific place, or through a network of coordinated projects in different locations.

Through understanding the process and effect of Van Eyck's Interstitial design strategy, the author hopes that the findings in this text can be understood as a plea for the importance and value of minimal, but meaningful interventions in scattered leftover spaces through creative, human-oriented,place making strategies.□