Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, an emerging pathogen in newborns:Three case reports and a review of the literature

Bijaylaxmi Behera

Bijaylaxmi Behera, Department of Pediatrics & Neonatology, Chaitanya Hospital, Chandigarh 160044, India

Abstract BACKGROUND Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (S. maltophilia) is a rare cause of neonatal sepsis with significant morbidity and mortality and has extensive resistance to several antibiotics leaving few options for antimicrobial therapy. Only a few cases have been reported in neonates from developing countries. We report three cases of critically ill, extramural babies with neonatal S. maltophilia sepsis. All three babies recovered and were discharged.CASE SUMMARY All three cases were term extramural babies, who were critically ill at the time of presentation at our neonatal intensive care unit. They had features of multiorgan dysfunction at admission. Blood culture was positive for S. maltophilia in two babies and one had a positive tracheal aspirate culture. The babies were treated according to the antibiogram available. They recovered and were subsequently discharged.CONCLUSION Although various authors have reported S. maltophilia in pediatric and adult populations, only a few cases have been reported in the newborn period and this infection is even rarer in developing countries. Although S. maltophilia infection has a grave outcome, our three babies were successfully treated and subsequently discharged.

Key Words: Ceftriaxone; Multidrug resistant; Neonatal sepsis; Stenotrophomonas maltophilia; Cotrimoxazole; Tigecycline

INTRODUCTION

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia(S. maltophilia) was previously known asPseudomonas maltophiliaorXanthomonas maltophilia[1]. It is currently an important multi-drug resistant, gram-negative, oxidase-negative, and catalase-positive, non-fermenting nosocomial pathogen associated with significant mortality[1].S. maltophiliais the only species ofStenotrophomonasknown to infect humans. It ranks third amongst the four most common pathogenic non-fermentingGram negative bacilli(NFGNBs), the others beingPseudomonas aeruginosa,Acinetobacter baumanniiandBurkholderia cepaciacomplex[2].S. maltophiliamay have varied manifestations such as bacteremia,pneumonia, urinary tract infection, meningitis, endocarditisetc[3]. It is found in water,sewage, soil, plants, animals and in hospital settings, and may also be isolated from washbasins, respirators, antiseptics, and medical devices leading to device-associated infections such as catheter-associated bloodstream infections, urinary tract infections,and ventilator-associated pneumonia[4,5]. The treatment ofS. maltophiliainfection is very difficult as it is intrinsically resistant to the majority of commonly used drugs,such as all Carbapenems, and Levofloxacin[6-9]. Strains are usually susceptible to Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole, but this combination is not used in neonates due to adverse effects. Strains have variable susceptibility to Ceftazidime[6,7].S. maltophiliahas a contrasting antibiotic susceptibility pattern to otherNFGNBssuch asA. baumannii,P.aeruginosaandBurkholderia cepacia, and the correct identification ofS. maltophiliais very important, as it has to be differentiated from these other organisms. However, it is very challenging for a routine laboratory to identifyS. maltophilia, due to its inert biochemical profile and difficulty in the interpretation of phenotypic characteristics.Subsequently, its correct identification is essential as no single drug is effective against allNFGNBs, which hinders initiation of appropriate empirical treatment resulting in increased morbidity and mortality[10].

CASE PRESENTATION

Case 1

Chief complaints:An out-born baby, delivered to a primigravida mother at 38 wk,with a birth weight of 3000 gviaa lower segment caesarean section (LSCS) due to fetal distress, cried immediately after birth, but developed severe respiratory distress in the form of retractions and grunting with pulse oxygen saturation of 84%.

History of present illness:The baby was started on oxygen by hood, and received intravenous fluids, Cefotaxime, Amikacin and Vitamin K. On day two of life, the baby’s respiratory distress worsened with chest X-ray suggestive of right lung pneumothorax and was referred to our hospital.

Physical examination:On admission, the baby had severe respiratory distress with a Downes score of 6/10 and features of shock such as weak pulse, prolonged capillary refill time (CFT), heart rate (HR) of 190 bpm, blood pressure (BP) of 40/28 mmHg and peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) of 82%. Right side air entry was decreased compared to the left side.

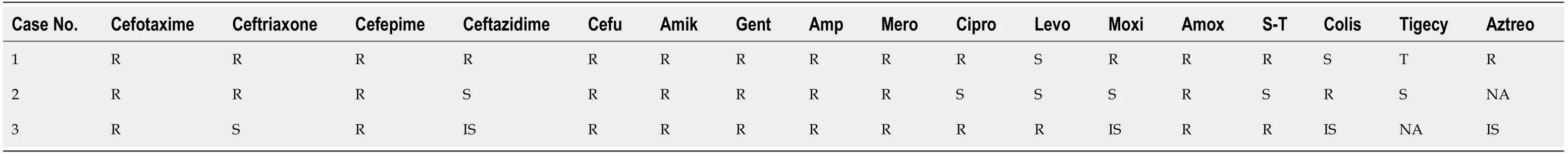

Laboratory examinations:A sepsis screen sent on admission was positive with procalcitonin (PCT) of 15.43 ng/mL, µESR of 12 mm, total leucocyte count (TLC) of 20300 and an IT ratio of 0.22. Blood culture sent on admission showed growth ofS.maltophilia(multi-drug resistant) (Table 1). Lumbar puncture (LP) was negative for meningitis.

Imaging examinations:Imaging showed right lung pneumothorax with left side consolidation.

Case 2

Chief complaints:A term, 37 wk out-born baby, weighing 2600 g, delivered by LSCS due to previous LSCS, cried immediately after birth but developed respiratory distress soon after birth.

History of present illness: The baby was started on oxygen andi.v. antibiotics. On day three of life, the baby’s respiratory distress worsened and the child was referred to our hospital.

Physical examination: On admission, the child had severe respiratory distress with a Downes score of 7/10 and had features of poor perfusion such as tachycardia (HR:185/min), CFT of more than 3 s, extremely weak pulse and unrecordable BP and SpO2.

Laboratory examinations:A sepsis screen sent on admission was positive with PCT of 25.3 ng/mL, µESR of 10 mm, TLC was 21200, platelet count was 44000 and IT ratio was 0.22. Prothrombin time (PT) was 22 s, INR was 1.8 and partial activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) was 64 s. Blood culture sent on admission grewS.maltophilia, and the sensitivity pattern is provided in Table 1. LP was negative for meningitis.

Imaging examinations:Chest X-ray on admission was suggestive of white out lungs.

Case 3

Chief complaints:A term 38 wk out-born baby boy was referred to our hospital with symptomatic hypoglycemia and respiratory failure.

History of present illness: A term 38 wk 2600 g, out-born male baby was delivered by LSCS due to non-progression of labor, to a 25-year-old primigravida mother who was leaking per vagina for 20 h. Antenatal history was uneventful. The child developed symptomatic hypoglycemia at 10 h of life with lethargy and one episode of seizures. A sepsis screen revealed C-reactive protein of 10.9 mg/L and the baby was started on Cefotaxime and Amikacin. He developed severe respiratory distress on day four of life and was intubated and then referred to our hospital on manual ventilation.

Physical examination: On admission, the baby was in shock with prolonged CFT,tachycardia (HR: 192/min, weak pulse, BP of 36/22 mmHg), posturing, and a SpO2of 95% on manual ventilation.

Laboratory examinations:A sepsis screen revealed PCT of 16 ng/mL, µESR was 12 mm and IT ratio was 0.20, platelet count was 23000 with a deranged coagulogram (PT:29 s, INR: 2, aPTT: 78 s). Arterial blood gas revealed mild metabolic acidosis. Blood culture isolatedStaphylococcus epidermidis; which was sensitive to Cotrimoxazole,Nitrofurantoin, Linezolid, Daptomycin, Teicoplanin and Vancomycin. Tracheal aspirate sent on admission grewS. maltophiliawhich was sensitive to Ceftriaxone and had intermediate sensitivity to Colistin, Aztreonam, Ceftazidime, Moxifloxacin and was resistant to Ampicillin, Amikacin, Gentamicin, Cefotaxime, Cefepime,Meropenem, Augmentin, Cefuroxime, Cefoxitin, Ciprofloxacin, Levofloxacin and Cotrimoxazole (Table 1).

Imaging examinations:Chest X-ray was suggestive of pneumonia. Cranial ultrasonography was suggestive of cerebral edema with chinked ventricles.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Case 1

Term/38 wk/AGA/S. maltophiliasepsis/septic shock/pneumonia/right sidepneumothorax.

Table 1 Antibiograms of the three cases included in this report

Case 2

Term/37 wk/AGA/S. maltophilia sepsis/septic shock/pneumonia/disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)/pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH).

Case 3

Term/38 wk/AGA/Staphylococcus epidermidis and S. maltophilia sepsis/septic shock/pneumonia/meningitis/DIC.

TREATMENT

Case 1

On admission, the baby had severe respiratory distress with a Downes score of 6/10 and features of shock. The child was intubated and was started on synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV) mode with settings of 13/04/60/100% and a pneumothorax was drained using an intercostal drainage tube. A normal saline bolus was followed by ionotropic support with Dopamine and Adrenaline and i.v.antibiotics Vancomycin and Meropenem were started. Colistin was added on day three after admission, as there was no significant clinical improvement. On the fourth day of life, the chest tube was clamped and removed. The baby was extubated on day five of NIMV mode with settings of 16/05/40/21% and gradually changed to nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). Subsequently, the baby was weaned to nasal prongs and finally oxygen support was stopped on the eighth day of life.Vancomycin, Meropenem and Colistin were given for a total duration of 14 d.Ionotropes were slowly tapered and finally stopped on day five of life. The baby was started on measured tube feeding and then gradually to spoon feeding and breastfeeding by day ten of life.

Case 2

A term, 37 wk out-born baby, weighing 2600 g, delivered by LSCS due to previous LSCS, cried immediately after birth but developed respiratory distress soon after birth and was started on oxygen andi.v.antibiotics. On day three of life, respiratory distress worsened and the baby was referred to our hospital. On admission, the child had severe respiratory distress with a Downes score of 7/10 and was in shock, the child was intubated and started on conventional ventilation but was changed to high frequency ventilation with a maximum setting of mean airway pressure of 18, inspired oxygen fraction of 100%, DP of 60, frequency-10 and required maximum inotropic support of Dopamine 20, Dobutamine 20, Adrenaline 0.5, and Milrinone 0.2 μg/kg/min. A chest X-ray on admission was suggestive of white out lungs; therefore,the baby was given surfactant and within 24 h was changed to conventional ventilation (SIMV mode 18/5/50/50%). The baby also had PAH and was given Sildenafil by injection. Meropenem and Vancomycin were also administered. Colistin injection was added on day three after admission due to worsening clinical condition with shock and DIC. In addition to DIC, the baby also had thrombocytopenia,coagulopathy manifesting as orogastric and ET bleeding and received multiple platelet, fresh frozen plasma and packed red blood cell transfusions. The ventilator setting was gradually tapered and the baby was extubated to NIMV mode on the twelfth day after admission, and changed to nasal CPAP by day fifteen after admission and off oxygen by day seventeen. Blood culture sent on admission grewS. maltophiliawith sensitivity to Tigecycline which was added and Colistin continued. The baby received Vancomycin for seven days plus Tigecycline and Colistin for fourteen days.Tube feeding was started on day six of life and gradually increased to full feeding by day eleven after admission. The baby was subsequently breastfed.

Case 3

The baby required ionotropic support with Dopamine, Adrenaline and intravenous fluids and was started on SIMV mode (18/6/45/50%). A sepsis screen was sent and the child was started on Meropenem, Vancomycin and Colistin. As the baby was critically ill and did not show an improvement in symptoms, Ceftriaxone was started and Meropenem was discontinued on day three after admission, as soon as the tracheal aspirate report was received. CSF analysis was performed after the platelet count had improved, which was suggestive of meningitis. The child received fresh frozen plasma and platelet transfusions for DIC. Ionotropic support was gradually tapered and then stopped by day seven after admission and tube feeding was started.The baby’s sensorium and spontaneous efforts improved and he was extubated on the eleventh day after admission and changed to NIMV mode (16/6/50/30%). He was subsequently weaned off to CPAP by day fourteen. He was gradually weaned off CPAP by day sixteen and oxygen by day eighteen. Intravenous antibiotics were administered for 21 d, and he received full tube feeding by day twelve after admission and direct oral feeding by day sixteen.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Case 1

The baby was discharged from hospital on day fifteen of life, was being breastfed and had normal neurological status. At follow-up, the baby was being breastfed and was neurologically normal.

Case 2

The baby was discharged after eighteen days of hospitalization. At follow-up, the baby was being breastfed and was healthy.

Case 3

The baby was discharged after almost twenty two days of hospitalization on full feeds.At follow-up, the baby was neurologically normal, on mixed feeds and repeat cranial ultrasound was normal.

DISCUSSION

S. maltophiliais currently an emerging multi-drug resistant, opportunistic pathogen in both hospital and community settings. Studies have shown various risk factors for infection or colonization byS. maltophilia, including prior use of broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents such as Carbapenem, Ampicillin, Gentamicin, Vancomycin,Metronidazole, Piperacillin, Cefotaxime, Ceftazidime, Ciprofloxacin, Tobramycin, and Cefepime, and other drugs such as corticosteroids, cytotoxic chemotherapy,immunosuppressive therapy, H2 blockers, and parenteral nutrition[11-16]. Prolonged hospital stay, invasive procedures including mechanical ventilation, intubation,urinary catheterization, central venous catheterization, lower gestational age and low birth weight, neutropenia, underlying diseases such as hepatobiliary, chronic pulmonary, and cardiovascular diseases, organ transplantation, dialysis, intravenous drug use, and human immunodeficiency virus infection, malignancy, and exposure to patients withS. maltophiliawound infection were significantly associated withS.maltophiliainfections[17-21]. In our patients we found that intensive care unit (ICU) stay,administration of broad spectrum antibiotics, and invasive procedures would have contributed to infection with this organism. Although according to the literature,premature and low birth weight babies are more prone to developing this infection, all our cases were term and with good birth weights[21].

According to Jiaet al[7], maximum isolation ofS. maltophiliawas from respiratory specimens, whereas Abdel-Azizet al[6], reported maximum isolation from urine samples followed by swabs and blood. In our cases,S. maltophiliawas isolated from blood in the first two cases and from tracheal aspirate in the third case. The identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing was carried out using VITEK and the results were confirmed with manual MIC calculations.

S. maltophiliahas several resistance mechanisms to various antibiotic classes such as beta-lactams due to two inducible beta-lactamases, a zinc-containing penicillinase (L1)and a cephalosporinase (L2), an aminoglycoside acetyl-transferase that confers resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics, and temperature-dependent changes in the outer membrane lipopolysaccharide structure confers added resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics and possesses efflux pumps[22,23]. Although according to previous reports the organism is resistant to the majority of commonly used drugs such as all Carbapenems and Levofloxacin, and is susceptible to Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole, with variable susceptibility to Ceftazidime[6-9], in our cases except for one, which was sensitive to Ceftazidime and the others were sensitive to Ceftriaxone, all were resistant to Aminoglycosides, Carbapenems, and Cephalosporins. Of the three cases, one was resistant, one was sensitive and one had intermediate sensitivity to Colistin. The first and second cases were sensitive to Tigecycline and in the third case sensitivity was not tested. Two cases were sensitive to Levofloxacin and one was resistant. One case was sensitive to Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole and two were resistant. We administered Colistin and Tigecycline to our patients. In the third case we administered Ceftriaxone, as the organism had intermediate sensitivity to Colistin and Tigecycline sensitivity was not performed. The same baby was monitored for serum bilirubin levels and for other adverse effects. As shown in the literature, Ceftriaxone can be used in neonates and is contraindicated in babies at risk of developing unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia and concurrent administration with calcium[24-26]. In our third case, although tracheal aspirate was positive forS. maltophilia, the baby was treated according to the antibiogram, as clinical features were consistent with the infection. However, most clinicians are reluctant to treat this pathogen, when isolated from tracheal aspirate and often treat it as colonization rather than a pathogen[27]. Antibiograms of the three patients are shown in Table 1.

Most infections caused byS. maltophiliaare associated with severe morbidity and long-term, extensive ICU treatment. According to previous reports, the mortality rates vary between 14%-62%[28,29]. Our three babies were discharged on full feeds with a hospital stay of 14 to 21 d.

CONCLUSION

Various case studies onS. maltophiliainfections in India, such asS. maltophiliaendophthalmitis[29], tropical pyomyositis[30], unilateral conjunctival ulcer[31], nonhealing leg ulcer[32]and meningitis[33], have been reported in pediatric and adult patients and the isolation rate ofS. maltophiliawas found to be 2.5% (5 isolates) out of 193NFGNBsin various clinical samples[34]. However, neonatal sepsis due toS. maltophiliahas been reported only by Viswanathanet al[1]and Sorenet al[35]. Here we report three cases of neonatal sepsis due toS. maltophiliaalong with their antibiograms AlthoughS.maltophiliainfection has a grave outcome our three out-born babies were successfully treated and discharged.

World Journal of Clinical Infectious Diseases2021年1期

World Journal of Clinical Infectious Diseases2021年1期

- World Journal of Clinical Infectious Diseases的其它文章

- Life after recovery from SARS, influenza, and Middle East respiratory syndrome: An insight into possible long-term consequences of COVID-19

- Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Louisiana - one-year follow-up: A case report

- Liver transplantation in patients with SARS-CoV-2: Two case reports