Didactics of Languages:Implementing Dynamic Exchanges and Enhancing the Potential of Creativity in a Mentoring Context

Euphrosyne Efthimiadou

Group dynamics is applied not only in the professional life but also in the educational framework becoming one of the tools of group therapy aiming at reducing conflicts and tensions. Under this perspective it would be interesting to study the dynamic exchanges that take place within the interrelations of the facilitator with his target group aiming at further exploiting the cognitive and affective resources of the participants in order to manage their potential more effectively and to accompany them in any training situation. From an actional perspective the adoption of collaborative tasks promotes cooperation and problem solving in a mentoring context, where the members invest in the realization of a meaningful action project in order to implement creative tasks and cultivate transversal skills using digital technology.

Keywords: dynamic exchanges, co-acting, creative potential, cross-cutting skills, mentoring

Introduction

Group dynamics is the driving motivation that regulates the behavior and attitudes of its members. It can become one of the tools of group therapy since it has applications not only in business and political life but also in interpersonal relations. Moreover, many studies show its beneficial influence in school life. In language didactics, the actional perspective is considered a new methodological trend, which places the learner at the heart of his/her learning process through the realization of more or less complex tasks. For the learner the development of cognitive but also affective resources gives rise to the exploitation of his/her hidden assets and encourages him/her to take a fresh look at his/her learning process in order to effectively manage his/her potential. As for the facilitator, the act of lesson planning and accompanying the learner in the learning situation means to fully explore the dynamics of information exchange. In this case, the elaboration of an action project which favors the mediation of the facilitator through a pedagogical dialogue, encourages autonomy and makes the learners responsible for learning. On the one hand, the language teacher must reflect on the curriculum and plan the collaborative tasks to be undertaken in order to capture the interest of the group. On the other hand, it would be useful to consider the pedagogical process that could lead to the mastery of skills while emphasizing cooperation, administration of learning strategies and problem solving. In this way the classroom will become a place of daily life since the members of the group invest in a meaningful action project that is carried out under pragmatic conditions.

Achieving Energetic Exchanges Through Group Dynamics

In the 1930s and 1940s, group dynamics emerged in the United States by three founding psychologists: Elton Mayo (1949) Jacob Moreno (1950) and Kurt Lewin (1947). First of all, Elton Mayo (1949) aimed to evaluate the impact of working conditions on productivity and emphasized that even a deterioration of those could lead to an increase in productivity. For Jacob Moreno (1950), sociometry makes it possible to detect links between members of a group by studying not only rational factors but also affective data above all. However, it is to the psychologist Kurt Lewin (1947) that the genesis of the study of group dynamics is attributed. Inspired by Einsteinian physics, Kurt Lewin (1947) considers that the dynamics of the group is governed by a “field of forces” which exerts their influence in parallel: roles, means of communication, type of leadership, norms and collective values, goals that the group sets to itself and actions that are carried out.

According to the systemic approach of the Palo Alto School (Gregory Bateson, inspirator of the group founded in 1952, Don D. Jackson, Jay Haley, Virginia Satir, Paul Watzlawick, etc.), when the problem of conflict management and change intervention arises, it is necessary to identify the mechanisms which obstruct people who are in interaction. For this reason, the approach to be adopted in order to conduct oneself while searching solutions can be divided into three phases: (a) the avoidance phase where one avoids any difficulty that arises; (b) the control phase during which one tries to maintain control of the established situation and c. the belief phase, through which one aims to conceive and contextualize the type of problem so as to be led towards change through trusting oneself (Arminot, 2018). Specifically, the Palo Alto School’s systems approach is based on four principles. First, the transmission of a message is translated into two levels of meaning: the content about what is said and the interpersonal relationship. Then there are two distinct modes in the communication of a message: (a) digital, containing the language and code to communicate; and (b) analog, referring to extralinguistic elements such as mimics and gestures or body posture. In addition, the punctuation of exchanges makes it possible to identify a sequence of segments affecting the behavior of the other. Finally, the effect of feedback, or even metacommunication, focuses on interpersonal exchanges carried out according to the two levels of meaning, or even content or relationship.

The great novelty brought by the Palo Alto School is to have put interpersonal communication at the center of its vision and to have proposed a rigorous formalization elaborated around some great principles: the primacy of the relationship over individuality; the fact that all human behavior has a communicative value and that all human phenomena can be perceived as a vast system of mutually implicating communications; the hypothesis that personality or psychological disorders can be reduced to disturbances in the communication between the individual, his environment and the context in which he evolves.(Picard & Marc, 2015, p. 3).

Therefore, this mutual exchange among the members of the group enables to cultivate their skills and to create favorable conditions for the expansion of their intellectual horizons without neglecting the positive contributions of their affective life in class. Certainly, training subjects to master their attitudes helps to control their deficits. Learners feel engaged in an action that optimizes their expectations. The gains of group work over individual work are: slight improvement in disciplinary learning, better long-term recall, intrinsic motivation, more positive attitude toward the subject matter, development of high-level Bloom’s Taxonomy goals.

In a language classroom, group dynamics are used to create opportune learning conditions. In this case, the role of the facilitator is essential because he is the one who can lead the group towards cooperation and problem-solving strategies. In this respect, it is a question of establishing an action project on the one hand, and of encouraging the construction of knowledge and working alliance on the other. Finally, it would be important to invite the group to adopt a methodological reflexivity that would guarantee the optimal performance in order to overcome any possible failure.

On his/her part, the educator leads the group towards awareness and active involvement in the educational process. What should characterize the interpersonal relationships of the members of a group is strategic cooperation and effective contribution to the accomplishment of the tasks with a specific objective. In this context, it is essential to tolerate differences in order to cultivate a sense of trust and self-worth. On the one hand, we can ask ourselves to what extent the leader succeeds in exerting an overriding influence on the group while encouraging the construction of knowledge. On the other hand, we should focus our interest on the working alliance and, more specifically, on the cohesion and dynamics of the exchanges in the interaction. Therefore, the availability and energy of all participants considerably influence the learning conditions and the atmosphere of the class. Through cooperation, it is possible to achieve the objectives set and optimize the group’s performance in order to carry out constructive tasks.

Adopt a Methodological Reflexivity to Ensure Optimal Performance

It is true that the group is more effective and creative if it is led towards the mastery of transversal skills. Learning differently means shifting the interest of the learning process on interdisciplinarity. In this case, the teacher could propose a pedagogy of alternation, opting to develop the skills of the group. Since we are interested in optimizing the audience’s expectations, it is essential to develop cross-curricular skills. “Developing communication skills, methodological thinking skills, the ability to enter into a project approach, the ability to enter into a self-evaluation approach: these are the four cross-cutting skills that can be worked on, improved and developed in the various learning situations and activities that feed the training project. These four abilities are cultivated during learning situations” (Jaligot & Wiel, 2004, pp. 128-129).

In an alternative pedagogy, the teacher plays the role of mediator in order to develop the act of learning. On the one hand, he helps his group to acquire new know-how while on the other hand he manages to instill self-confidence in order to undertake effective initiatives. Thus, the notion of resilience is presented as an inner strength that derives from the experiences acquired to solve problems and successfully face the risks of life. During school life shocks and traumas are overcome by the ability to deal with those problems with perseverance and optimism. Certainly, the awareness of the resources that can be activated allows one to resist stress and overcome school difficulties in order to search for new connections in his school career or to cultivate new ones.

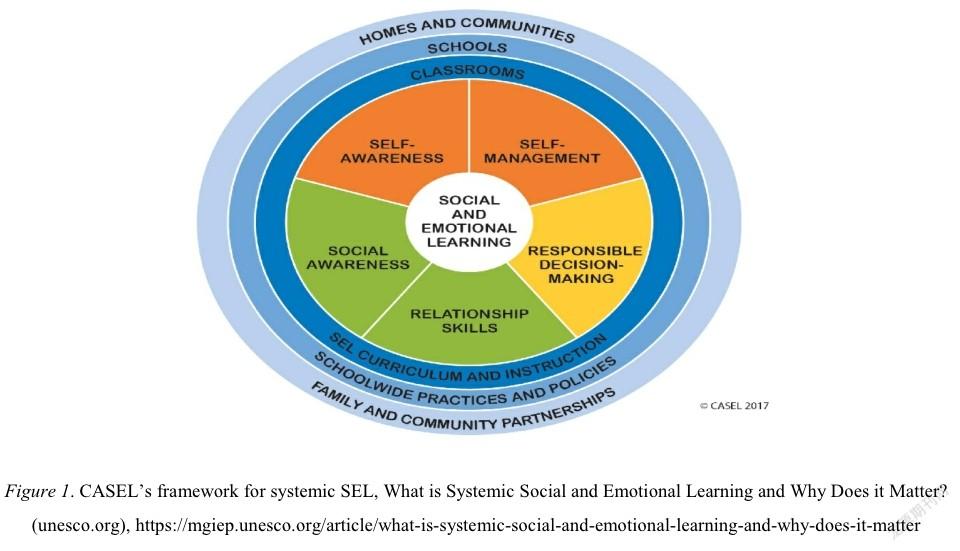

The areas of application of group dynamics can be practiced in daily life where increase of self-awareness and personal effectiveness can be envisaged. They concern: (a) Negotiation groups; (b) Training in universities, commerce, industry, the army; (c) Psychosociological intervention through the group in organizations; (d) Social therapy in social activities (theater, party, leisure clubs…); (e) Work or family groups. The overall aim is to cultivate individual skills through systemic social and emotional learning and stimulate power in order to achieve the objectives set.

The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) has defined social and emotional learning (SEL) as “(…) the process through which children and adults understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions” (CASEL. (2019a), https://casel.org/core-competencies/). From this perspective, learning, which takes into account psychomotor investment is reinforced by self-management and self-regulation. “Certainly, the information received, exploited and decoded helps to bring meaning to the situations put in context because the operations of decoding and encoding of the information connect and highlight the cognitive aspect but also the affective dimension in the elaboration and management of the tasks to be performed” (Efthimiadou, 2021, p. 5).

For his/her part, the facilitator creates balanced relationships and remains concerned with the adoption of a pedagogical approach which can be distinguished in three stages: (a) observation; (b) analysis; (c) conceptualization. At the same time, he/she carries out a dynamic procedure that includes: (a) classification of the different groups; (b) observation of the phenomena; (c) identification of the factors and their effectiveness. Therefore, the progressive training of the learners in tasks that encourage initiative results in their mastery of attitudes, so that the group feels better organized and able to develop communicative and transversal skills.

Certainly, the contact among the group members controls the deficits and allows to fill them in order to set the group dynamics free through the realization of authentic communication. The implementation of strategies that develop transversal competences enriches the educational context with tendencies that stimulate taking initiative in the group. Far from any form of failure, teacher and student interact in a reciprocal way in order to guarantee an optimal performance in the group. Thus, awareness of the pedagogical situation consists of a primordial step towards carrying out tasks that allow to adopt the necessary eagerness in the learning process and to contribute to tactics for success.

Alternative and Active Pedagogies Enhance the Potential of Creativity in a Mentoring Context

Alternative and active pedagogies are holistic methods that focus on the students’ interests and place them at the heart of the educational project. Numerous approaches adapt to the learning context while respecting the rhythm of each learner according to his/her true needs to be creative. Under this aspect, the participant feels motivated to take part in a scenario-action designed to make him/her responsible while developing his/her autonomy and giving room to his/her freedom to co-act with the other members of the group and broadly with his/her community.

Throughout the 20th century, Decroly (1921), Freinet (1968) and Montessori (1967) advocated pedagogical approaches based on free development, self-discipline and experiential learning aiming to accompany and guide the learner by knowing how to support him/her on the physical, emotional and behavioral level.

The implementation of alternative and active pedagogies in the context of language teaching/learning is becoming a new challenge to develop the group’s dynamics and to ensure the learners’ mentality evolve in a creative and innovative way. Active and alternative pedagogies are at the heart of current training to integrate migrant populations into the socio-professional context by respecting the rhythm and cooperative management of acquisition while promoting learning by experience.

Moreover, these alternative pedagogies are focused on reducing social inequalities and increasing the success rate of the subjects trained. In this sense, the mentor’s contribution is essential to help each participant acquire cross-cutting skills, in order to create effective synergies through collaboration in action. The educational approach adopted aims at fostering communication skills and community involvement through the development of cooperative action projects, which promote learning through face-to-face or even distance mentoring. As for the mentor-teacher, he/she becomes a proficient strategist who plans his/her action according to the skills level of each learner at the time and is concerned with developing human potential.

Thus, the learner’s investment succeeds in reconciling the information disseminated with his/her experience, blending the fictional and authentic worlds at the same time. From the actional point of view, the contribution of the imagination enriches the established situation with new elements that the group itself invents. From a psychological point of view, the participants manage to overcome their first obstacles by progressively increasing their performance. Far from feeling marginalized, they feel responsible for their learning path divided into milestones, where they can return and test their performance. Moreover, as Bandura points out,

To reinforce the feeling of personal effectiveness, the trainer or teacher must encourage the learner and offer him tasks whose difficulty he controls: too difficult, they confront failure and diminish the feeling of personal effectiveness; too easy, they do not train in problem solving. (Bandura, A. April, 2004, p. 45)

Thus, one manages to master, in progressive steps, what had previously appeared difficult or what was synonymous with failure, putting aside any phobic feelings or stressful situations and investing in everything that fulfills one’s dreams and sensations.

As a result, we can propose an action-based pedagogy where the tasks become pragmatic and are based on authentic situations. The process of learning is personally or socially valued because subjects are invited to reuse micro-expertise acquired on combined tasks that highlight their skills. This actional perspective of learning gives a praxeological dimension to the transfer of data in convergent and divergent contexts. There are certain pedagogical applications that develop exchanges among group members while suggesting activities with an intercultural and/or formative purpose. One could distinguish three successive stages of exploitation of any task to be undertaken:

(a). the connection with another parallel situation

(b). the complementary or contiguous approach

(c). divergent operations that lead to original options

In this way, the task is embedded not only in a well-defined linguistic but also in a social context, which gives it its full meaning. In this way, a planning of discourse strategies can be realized with the help of sophisticated technological tools for mediation. As Lomicka and Williams point out,

The tools that had the greatest potential for development include video conferencing, podcasts, Internet activities, blogs, chat and discussion boards. We found it interesting that teachers mentioned writing as the skill with the most potential for development with regard to new technologies. Dialogue that takes place in blogs, chat and discussion board-all belong to a new hybrid form of communication that links both speech and writing (…). (Lomicka & Williams, March 2011, p. 779).

In this perspective, digital technology with the advent of Web 4.0 is focused on more active users while promoting collaboration and information sharing. Thus, computer systems occupy a significant place in the courses of languages following the most recent and pioneering advances while offering participants new and more enriched applications so as to move from the stage of reception to that of exploitation-production of digitized information. As Efthimiadou points out,

E-learning offers the opportunity to combine flexible communication tools and applications that can be easily managed, such as forums, e-mail, video-conferencing, and the virtual classroom (e-classroom). In addition, it is possible to offer enriching collaborative interactive activities through the use of wiki or blogs but also through information sharing and online communication to develop simulations or even online pedagogical scenarios. (Efthimiadou, 2019, pp. 45-46).

Conclusion

Therefore, the need to place the learner at the heart of the learning process and to focus on the act of learning through his/her experience gives rise to pragmatic situations. It is important to engage learners in a reflective process where varied and realistic tasks are used to optimize their expectations but also to open up new avenues for them to become autonomous. The ultimate goal would be to lead the participants to develop the skill of learning how to learn through research and data exploitation. As Perrichon points out,

The strategies put in place by the social actor in society and those developed by the learners in the classroom should therefore be, they too, in an interdependent relationship. As such, they appear to be an enactment of social, cognitive and metacognitive processes; social because they are related to what the learner has to do in society, parallel to or subsequent to his learning; cognitive because the strategies are phenomena pertaining to the process of acquiring information; metacognitive because they allow for the implementation of reflective practices that enable the learner to adjust his or her actions in society according to the strategies he or she has developed during the course of learning. (Perrichon, 2008, p. 165).

Ultimately, mentoring is equipped with technological tools, so that participants can better benefit from collaborative tasks while cultivating cross-cutting skills.

In the context of collaborative distance learning, the mentor’s contribution proves to be essential to implement an actional pedagogy where participants will be able to optimize their expectations through the implementation of online collaborative tasks and the adoption of an interactive project pedagogy and the integration of both new open and distance learning (ODL) devices, with a view to achieving self-fulfillment and satisfying the new requirements that are being created in training. (Efthimiadou, 2019, p. 48).

References

Arminot, F. (Novembre 2018). Approche systémique de Palo Alto: Conduire le changement. Accessible sur: https://fredericarminot.com/anxiete/approche-systemique-de-palo-alto/, consulté le 05-10-2021.

Bandura, A. (Avril 2004). Le sentiment d’efficacité personnelle. Revue des Sciences Humaines, 148, 42-45.

CASEL. (2019a). Core SEL competencies. Retrieved from: https://casel.org/core-competencies//

Decroly, J.-O., & Boon, J. (1921). Vers l’école rénovée-une première étape. Brussels/Paris, Office de Publicité/Lebègue-Nathan.(Republished 1974).

Efthimiadou, E. (2019). Hot and cold cognition in hybrid communication. Frontiers in Education Technology, 4(3), 1-7. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.22158/fet.v4n3p1

Efthimiadou, E. (2019). La contribution du mentor: Gérer le parcours de formation des enseignants par l’adoption de pratiqueséducatives novatrices à l’ère du numérique. 4e édition de la Conférence Internationale éducation et Spiritualité, Le mentorat et les parcours flexibles de l’éducation. Bucure?ti : Editura Universitar?. 40-48.

Freinet, C. (1968). Essai de psychologie sensible appliquée à l’éducation. Neuchatel: Delachaux & Niestle.

Jaligot, A., & Wiel, G. (2004). Construire des stratégies de nouveau départ. Lyon: Chronique Sociale.

Lewin, K. (1947). Frontiers of Group Dynamics: Concept, method and reality in social science, social equilibria, and social change. Human Relations, 1, 5-41. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1177%2F001872674700100103

Lomicka, A. L., & Williams, L. (March 2011). The use of new technologies in the French curriculum: A national survey. The French Review, 84(4), 764-781.

Mayo, E. (1949). The social problems of an industrial civilization. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Montessori, M. (1967). The absorbent mind. New York: Delta.

Moreno, J. L. (1950). The sociometric approach to social case work. Sociometry, 13(2), 172-175.

Perrichon, E. (Octobre 2008). Agir d?usage et agir d?apprentissage en didactique des langues-cultures étrangères, enjeux conceptuels, évolution historique et construction d?une nouvelle perspective actionnelle. Thèse de doctorat. Accessible sur: http://www.aplvlanguesmodernes.org/spip.php?article2029, consulté le 10-10-2021.

Picard, D., & Marc, E. (2015). L’Ecole de Palo Alto. Paris : PUF, Collection ? Que sais-je ? ?.

Journal of Literature and Art Studies2021年10期

Journal of Literature and Art Studies2021年10期

- Journal of Literature and Art Studies的其它文章

- Study on Decorative Patterns of Ceramic Landscape Paintings in Qing Dynasty

- The Chinese-English Translation of Sun Tzu’s Art of War from the Perspective of Bourdieusian Sociology

- Multimodal Discourse Analysis—A Corpus-based Study

- Indirect Request’s Processing Based on Force-Dynamic Theory

- The Media Images of Old Influencers on TikTok:A Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis

- The Desirability of Integrating Chinese Culture into College English Teaching:A Case Study