A Contrastive Study of the Semantic Prosody of Degree Adverbs

YANG Dou-dou

If the collocation of a word creates a semantic atmosphere in the context, it will infect the word, so that it has a certain semantic prosody. Based on corpus, this paper chooses ting (挺) and guai (怪) as a case study. This study combines description and interpretation, qualitative and quantitative analysis, and uses semantic prosody theory and related software technology to make a contrastive analysis of semantic prosody of degree adverbs ting (挺) and guai (怪) from synchronic and diachronic perspectives. We find that the semantic prosodies of ting (挺) and guai (怪) belong to positive prosody and negative prosody respectively, which are related to grammaticalization.

Keywords: semantic prosody, degree adverb, corpus linguistics

1 Introduction

1.1 Theory of Semantic Prosody

Based on the concept of “prosody” of Firth (1957), Sinclair (1991) developed a new term “semantic prosody”. According to him, corpus research indicates that collocations of lexical items show a certain semantic tendency: certain lexical items, habitually, might be coupled with certain semantically equal items to form collocations. The latter and the whole context is endowed with relevant semantic features and a certain semantic atmosphere, as these items and keywords with the same semantic characteristics appear frequently in the text. Such an atmosphere created by collocation is called semantic prosody.

The research of semantic prosody involves “colligation”, “node word”, and “span”, etc. Colligation refers to an abstract representation of collocations instead of a specific one, which can also be understood as a collocation formula between grammatical structures (Wei, 2002). For example, the structure “ting (挺) + adj” is a colligation, which represents a kind of collocation between adverb “ting (挺)” and adjectives. More corresponding examples can be “ting (挺) beautiful”, “ting (挺) ugly” and so on. Node words, also known as key words, are the objects of semantic prosody research, such as “ting (挺)” and “guai (怪)” studied in this paper. Span refers to the distance between the collocation word and the node word, which is calculated in terms of words.

According to Stubbs (1996), semantic prosody can be divided into positive prosody, negative prosody, and mixed prosody. Technically, they all refer to the collocation tendency of node words.

1.2 Cause for This Topic

Both “ting (挺)” and “guai (怪)” have similar meanings and colloquial nature. After discovering that the definitions of “very and strange” in Xinhua Dictionary are both “很 (very)”, Ma Zhen (1991) elaborated the meanings and usages of the two and found that “ting (挺)” is usually used in a neutral way, while “guai (怪)”contains feelings such as intimacy, satisfaction, caress, and naughtiness. Deng Bei (2013), Huang Yao (2015), Yang Simiao (2019), and others further explained the degree adverb “ting (挺)” and “guai (怪)” from the aspects of collocation, syntactic position, and diachronic change. Although these studies are very close to the study of semantic prosody and have certain enlightenment significance for this paper, they are still limited to traditional example analysis and description, lacking the support of data and a more reasonable explanation. Therefore, whether the conclusions obtained are reliable remains to be confirmed.

1.3 Research Methods

In terms of building the corpus, 10,000 entries containing “ting (挺)” and “guai (怪)” were downloaded respectively through the Corpus of Beijing Language and Culture University (BCC corpus); the examples of“ting (挺)” as quantifiers, adjectives and verbs, and “guai (怪)” as adjectives and verbs do not fit for this study were screened out manually. In the end, the same category items are deleted, leaving 6,632 corpora of “ting(挺)” and 1,406 corpora of “guai (怪)”, which are the basic index corpus for this study.

In terms of technical methods, this paper uses Excel, MyTxtSegTag, AntConc3.2.0w, and R software to analyze the sample corpus, then presents the differences of degree adverbs “ting (挺)” and “guai (怪)” through data statistics and charts.

2 Colligations of Degree Adverbs “Ting (挺)” and “Guai (怪)”

Both degree adverb “ting (挺)” and “guai (怪)” belong to the generalized metric space (Zhang, 2000). The index corpus will be used to summarize their colligation mode to try out the appropriate span for each semantic prosody by comparing the differences of their colligations.

2.1 Colligation of the Degree Adverb “Ting (挺)”

There are six basic colligations of “ting (挺)”, which are as follows:

First, “ting (挺) + AdjP” with “ting (挺)” modifies the adjective, which is the most typical and prevalent colligation. And there are some cases in which “ting (挺) + Adj” is followed by “de (的)” or modal particles.

Second, “ting (挺) + VP” with “ting (挺)” modifies the verb, which mainly includes mental verbs, can-wish verbs, and the existential verb “有”. There are also some cases where “ting (挺) + VP” is followed by“de (的)” or modal particles.

Third, “ting (挺) + NP”. At first, the degree adverb “ting (挺)” does not function as a modifier for nouns or noun phrases. With the constant change of language itself, the colligation “ting (挺) + NP”, however, has gradually been accepted and recognized by the public. There are also some cases where “ting (挺) + NP” is followed by “de (的)”.

Fourth, “Adv + ting (挺) +Adj”. The adverb used before “ting (挺)” is “zhen (真)”, which mostly has an emphasized meaning or role in the sentence.

Fifth, “ting (挺) + Adv + Adj”. The adverb used after “ting (挺)” is “lao (老)”, which mostly has an emphasized meaning or role in the sentence.

Sixth, “ting (挺) + Pro”. The pronoun that used after “ting (挺)” is “shenme (什么)”, which is uncommon and is usually a part of spoken language.

2.2 Colligation of the Degree Adverb “Guai (怪)”

There are three basic colligations of “guai (怪)”, which are as follows:

First, “guai (怪) + AdjP”, which is mostly followed by “de (的)” to be “guai (怪) + AdjP + de(的)”, or combined with modal particles such as “ne (呢)” to be “guai (怪) + AdjP + modal particle”. A separate “guai(怪) + AdjP “ structure is not common.

Second, “guai (怪) + VP”, with verbs including mental verbs, causative verbs, and the existential verb“you (有)”. Sometimes “guai (怪) + VP” will be followed by “de (的)” to be “guai (怪) + VP + de (的)”.

Third, “guai (怪)” with other adverbs. The adverb that used before “guai (怪)” is “zhen (真)”, which mostly has an emphasized meaning or role in the sentence.

2.3 Comparison of Degree Adverbs “Ting (挺)” and “Guai (怪)” Colligation

Comparing the “ting (挺)” and “guai (怪)” colligation, these two words have colloquial nature in common, which can directly modify adjectives or verbs as attributives, predicates, adverbials, and complements. The differences are:

(1) “ting (挺)” can be paired with nouns to be a colligation “ting (挺) + NP”, while “guai (怪)” should not be used with nouns.

(2) “ting (挺)” can be paired with nouns to be a colligation “ting (挺) + Pro”, while “guai (怪)” should not.

(3) “ting (挺)” can be paired with other degree adverbs to be colligations “zhen (真) + ting (挺) + Adj”and “ting (挺) + lao (老) + Adj”; while “lao (老)” is used after other adverbs, which is the only colligation “zhen (真) + guai (怪) + Adj + de (的)”.

(4) The collocation degree of both “ting (挺) or “guai (怪) + Adj” and “ting (挺) or guai (怪) + VP” with“de (的)” is different. Ma Zhen (1991) believes that when “ting (挺)” modifies the descriptive and verbal components, it needs or needs not to be followed by “de (的)”; while as a degree adverb, “guai(怪)” must be coupled with “de (的)”. According to the book “Eight Hundred Words in Modern Chinese” (2006), the adjectives and verbs modified by “ting (挺)” are often followed by “de (的)”; while as a degree adverb, “guai (怪)” is usually coupled with “de (的)”. Based on their colligations, it can be seen that “de (的)” used after “ting (挺) or guai (怪) + Adj” and “ting (挺) or guai (怪) + VP” is not mandatory. But in general, it is more mandatory after “ting (挺) or guai (怪) + VP” than “ting (挺) or guai (怪) +Adj”.

3 Semantic Prosody of Degree Adverbs “Ting (挺)” and “Guai (怪)”

It can be seen from the colligation that both “ting (挺)” and “guai (怪)” are mainly right-matched, accordingly, this paper chooses [0.2R] span when using Antconc for statistics. Wang Laping (2006) found that terms with T value>=2.33 and MI value>3 are typical and commonly used collocations. Since MI value cannot be counted in this study, only T value is referred to in the specific statistics, and the specific value range is adjusted according to the actual situation.

3.1 Semantic Tendency Statistics of the Degree Adverb “Ting (挺)”

As for the degree adverb “ting (挺)”, since a large number of words to be counted that with low T value have little impact on the result, the collocation with T value greater than 3 is selected as the statistical object, which shows in Table 4.

The specific criteria for the semantic tendency of this study are as below:

(1) Active collocation: Combining the context and specific collocations, those have positive, commendatory, and satisfactory emotions are active collocations.

(2) Negative collocation: Combining the context and specific collocations, those have negative, derogatory, disappointing emotions are negative collocations.

(3) Neutral collocation: those state objective facts without obvious emotions are considered neutral collocations.

According to the above criteria, the semantic tendency statistics of “ting (挺)” are listed in Table 5.

According to the data of semantic tendency statistics, it can be found that there are 93 typical collocations of “ting (挺)” and 4,717 word frequencies in total. Among them, there were 66 positive collocations with a total word frequency of 3,730, accounting for 79% of the total words. 16 negative collocations with a total word frequency of 327 frequencies, accounting for 7% of the words. And 11 neutral collocations with a total of 660 frequencies, accounting for 14% of the words.

3.2 Semantic Tendency Statistics of the Degree Adverb “Guai (怪)”

Forasmuch as there are few corpora for the degree adverb “guai (怪)”, the collocation with T value>2 is selected as the statistical object:

The specific criteria for the semantic tendency “guai (怪)” are consistent with “ting (挺)”, which are listed in Table 7.

According to the data of semantic tendency statistics, it can be found that there are 43 typical collocations of “guai (怪)” and 959 word frequencies in total. Among them, there were 10 positive collocations with a total word frequency of 216, accounting for 22% of the total words, 31 negative collocations with a total word frequency of 717 frequencies, accounting for 75% of the words. And 2 neutral collocations with a total of 26 frequencies, accounting for 3% of the words.

3.3 Semantic Prosody Descriptions of Degree Adverbs “Ting (挺)” and “Guai (怪)”

Duan Xiaoyan (2015) defined the critical value of positive, negative, and neutral semantic prosody as 65%, 71%, and 75% of the total number of words by searching for breakpoints in the scatter diagram. Based on this, this paper reckons that when the proportion of positive collocation words of a certain semantic tendency exceeds 65%, it can be considered that such degree adverbs have a clear positive semantic tendency; when the proportion of negative collocation words of a certain semantic tendency exceeds 71%, these degree adverbs have an obvious negative semantic tendency. With respect to that, we can differentiate what kind of semantic prosody “ting (挺)” and “guai (怪)” belongs to respectively.

Therefore, according to the proportion statistics, the degree adverb “ting (挺)” belongs to positive semantic prosody, while the degree adverb “guai (怪)” belongs to negative semantic prosody.

4 Semantic Prosody of “Ting (挺)” and “Guai (怪)” and Their Differences from a Diachronic Perspective

Based on the investigation and collation of ancient Chinese corpus in the Center for Chinese Linguistics PKU (CCL) according to eras including the Spring and Autumn Period, Warring States Period, Han Dynasty, Six Dynasties, Tang, Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing Dynasties, this paper throws light on the grammaticalization process and differentiated semantic prosody of “ting (挺)” and “guai (怪)” from a diachronic perspective.

4.1 Grammaticalization of the Degree Adverb “Ting (挺)”

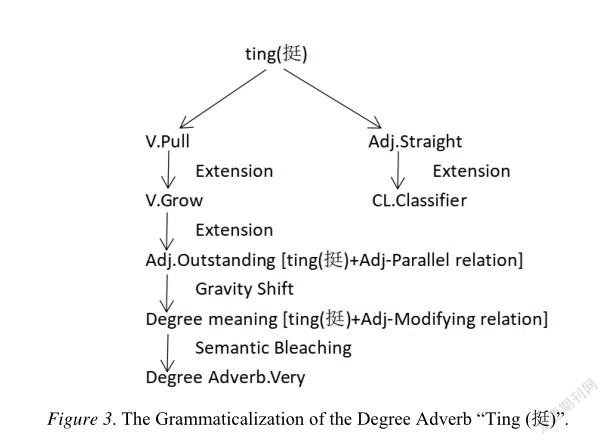

According to ShuoWenJieZi by Xu Shen, “挺, 拔也, 從手, 廷声.” In other words, the original meaning of “ting (挺)” is the verb “pull”. It has developed the adjective meaning “straight” in the Spring and Autumn Period, and the meaning of “growth” in the Warring States Period, in which classifiers was extended from the adjective “straight”. During the Han and Six Dynasties, the verb meaning developed into “stand up straight”and “stiff”, as well as the new meanings of “stick out and protrude” developed on from the previous generations, coupled with a large number of disyllabic adjectives with “ting (挺) + adj coordinate structure”. In the Tang Dynasty, the meaning of “ting (挺)” remains the same in general, but there are many “ting (挺) + NP”structures, most of which are followed by disyllabic or polysyllabic nominal structures. In Song Dynasty, the structure of “ting (挺) + adj + 之 + NP” increased gradually, and “ting (挺)” begins to be a function word. In Yuan and Ming Dynasties, although there are some uses such as “ting (挺) hard”, it still represents the coordinate elements of adjectives, which is the transitional stage of adverbialization of “ting (挺)”. In corpus of Qing Dynasty, the prejudiced construction of “ting (挺) + adj” appears in large numbers, meanwhile, the semantic focus of the whole structure had changed. The overall usage is basically the same as that of modern Chinese, and the adverb formation of “ting (挺)” is basically completed. In conclusion, the grammaticalization of degree adverb “ting (挺)” is as follows:

4.2 Grammaticalization of the Degree Adverb “Guai (怪)”

According to ShuoWenJieZi, the word “guai (怪)” has “heart” as its Chinese radical, “怪, 異也, 从心, 圣声.” The original meaning of “guai (怪)” is the adjective “weird”. But in the Pre-Qin Period, “guai (怪)” has developed the adjective “weird”, the verb “blame”, and the noun “strange things”. In the Warring States Period, it has developed the usage of verbs derived from adjectives and nouns, namely, “believe something is weird”. In Han Dynasty, the structure “strange + VP” appears, but the disyllabic word is limited to “guai (怪) ask”. In Six Dynasties, the “guai (怪) + VP” gradually appears, and the disyllabic words have developed “guai (怪) smile”, etc. From Tang Dynasty to Yuan Dynasty, the structure “guai (怪) + VP” has been increasing with a wider range of VP. The focus of the word has gradually moved back, and the degree meaning of “strange” has gradually strengthened. Until Ming Dynasty, it begins to appear as a degree adverb, in spite of the semantic characteristics of “weird”. The adverbialization of “guai (怪)” in Qing Dynasty is basically completed. In conclusion, referring to Deng Bei (2013), the grammaticalization of the degree adverb “guai (怪)” is summarized as follows:

4.3 Reasons for the Difference Between the Semantic Prosody of Degree Adverbs “Ting (挺)” and “Guai(怪)”

In summary, the main reasons for the difference between the two words are:

(1) The original meanings of the two are different. The original meaning of “guai (怪)” is negative for“weird” semantics, and its extended meaning is mostly negative; while the original meaning of “ting(挺)” is “pull”, which is semantically neutral, and its extended meaning is mostly positive. It is this semantic feature that affects their collocation tendency in the process of grammaticalization.

(2) Their grammaticalization process is different. “ting (挺)” has the degree meaning generated by the gradual backward shift of the focus of “ting (挺) + ADJP parallel structure”; while “guai (怪)” has the degree meaning produced by the gradual backward shift of the focus of “guai (怪) + VP serial verb construction”. “ting (挺) + ADJP” is mostly positive, while “guai (怪) + VP” is mostly negative. Under this influence, the collocation tendency of the adverb “ting (挺)” still tends to be positive, and that of the adverb “guai (怪)” still tends to be negative.

(3) In the later grammaticalization, the semantic meaning of adverbs “ting (挺)” and “guai (怪)” is weakened while the grammatical functions of these two are enhanced, and the range of collocation is expanded, resulting in the negative collocation of “ting (挺)” and the appearance of many positive and neutral collocation of “guai (怪)”. Compared to “ting (挺)”, although the proportion of “guai (怪)” in negative semantic prosody is decreased and the proportion of neutral and positive is increased, it is still relatively negative.

5 Conclusion

Through semantic prosody and its technical methods, this paper selects the adverbs “ting (挺)” and “guai(怪)” for comparative study, elaborating the differences between these two in terms of colligation, semantic prosody tendency, high frequency collocation words, grammaticalization process, etc., which are listed in Table 8.

References

Deng, B. (2013). Adverbialization of “怪” and “怪 XP (DE)” structure. Journal of Shanghai Normal University.

Firth, J. R. (1991). Papers in linguistics. London: Oxford University Press.

Hu, J. S. (2017). A comparative study of restrictive adverbs based on semantic prosody (Beijing Normal University).

Huang, Y. (2015). Adverbialization of “挺” and “ 挺 XP (DE)” structure. Journal of Shanghai Normal University.

Ma, Z. (1991). Adverbs of degree “很”“挺”“怪” and “老” in Mandarin. Chinese Learning, (2), 8-13.

Sinclair, J. (1991). Corpus, concordance, collocation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stubbs, M. (1996). Text and corpus analysis. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Wang, L. P. (2006). Quantitative analysis of word collocation. Journal of Shanghai Normal University,35(6), 117-122.

Wei, N. X. (2002a). General methods of semantic prosody research. Foreign Language Teaching And Research, (4), 300-307.

Wei, N. X. (2002b). A corpus based and corpus driven study of word collocation. Contemporary Linguistics, (2), 101-114+157.

Yang, S. M. (2019). A study of modern Chinese adverbs “很”, “挺” and “怪” (Liaoning University).

Zhang, X. Y. (2015). A study on the semantic prosody of degree adverbs in modern Chinese (Shanghai University).

Zhang, Y. S. (2000a). Function words in modern Chinese. Shanghai: Huadong Normal University Press.

Zhang, Y. S. (2000b). A study of adverbs in modern Chinese. Shanghai: Xuelin Press.

Zhang, Y. S. (2000c). The mechanism of grammaticalization related to Chinese adverbs—The nature, classification and scope of adverbs in modern Chinese. Chinese Language, (1), 3-15+93.

Journal of Literature and Art Studies2021年5期

Journal of Literature and Art Studies2021年5期

- Journal of Literature and Art Studies的其它文章

- Reading Trauma in Colum McCann’s“Step We Gaily,On We Go”

- On the Death of Tess—the Innocent Woman

- Friedrich Nietzsche’s Glorification of War

- Analysis of English Humor in Two Broke Girls from the Perspective of Cooperative Principle

- Dialogic Awareness in English Academic Writing Course for Chinese Graduate Learners

- A Study on the Negative Phonetic Transfer of English Learners in Henan Province