Making Meaning through Prepositions: A Model for Teacher Trainees

Ghsoon Reda

Sohar University, Oman

Abstract This paper proposes a cognitive-semiotic model for teaching English prepositions within teacher training programs. The model is presented as a three-session grammar module that involves 1) creating an environment for the learners to see prepositional polysemy as multiple ways of viewing Trajector (TR)-Landmark (LM) spatial configurations (Tyler & Evans, 2003, 2005) and 2) guiding them to make meaning through prepositions in the context of Radden and Dirven’s (2007) event schemas. This is a simplex to complex inventory of constructions for talking about world events (i.e. the material, psychological and force-dynamic world events) that can be presented as manipulations of a basic TR-LM spatial configuration. Such a module is useful for native and non-native English teacher trainees alike considering that it allows for covering prepositional polysemy and use in a systematically graded manner, a manner that may help teacher trainees to learn to prepare conceptually-linked, graded materials for teaching prepositions to EFL (English as a foreign language) learners.

Keywords: cognitive grammar, Conceptual Metaphor Theory, event schemas, event settings, prepositional meaning, semantic roles

1. Introduction

The development of theoretical work on teaching the prepositions of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) may be described as representing a shift of focus from the lexical to the semantic dimension of the items, a shift that may be introduced as triggered by the following questions: “What prepositions do EFL students need to learn?” and “What is an effective way for teaching prepositional polysemy to these students?” The practice of teaching prepositions, however, rests on dealing with the items as homonyms rather than polysemes (Tyler & Evans, 2003). It can be said that prepositions in EFL materials are simply different sets of words that meet the general needs of learners (e.g. prepositions of time, place, movement, and so on). The point here is that despite the wide range of purposes that English serves nowadays, the question of what words EFL students need to learn is still being raised and addressed by compiling word lists on the basis of such criteria as usefulness, frequency and ease. For example, what started as West’s (1953) General Service List and Academic Word List (see Coxhead, 2000) developed to the following lists to play complementary roles in meeting the needs of EFL learners: the New General Service List and the New Academic Word list (Browne, Culligan & Phillips, 2013). The particularly negative effect of this on prepositions is beyond the exclusion of some of the items from EFL materials. It concerns the lack of coverage in regard to the diverse roles that prepositions play in meaning making at the sentence level. Thus, the focus on prepositional phrases in EFL materials as a response to observations in regard to the idiomatic nature of vocabulary (including prepositions) (see Willis, 1990; Celce-Murcia & Larsen-Freeman, 1999) is not a remedying treatment. Prepositions are the building blocks of the semantic and grammatical structures of English, and they need to be presented as such.

The model proposed in this article attempts to achieve this. It links prepositional polysemy and use through the TR-LM configurations in the context of Radden and Dirven’s (2007) event schemas—a simplex to complex inventory of constructions for talking about world events (the material, psychological and force-dynamic world events). Event schemas have been chosen on the basis of their correspondence with prepositions in terms of semantic structure. In addition, they have the potential to provide opportunities for learning prepositions through meaning making in the sense that the different event schemas can be built through different semantic roles and prepositional constructions can assume all participatory and non-participatory roles configuring the schemas. Participatory roles, such as GOAL and RECIPIENT, are components of event schemas, whereas non-participatory roles are adjuncts that can be attached to the schemas to define the spatial, temporal and causal event settings. Such a semiotic approach does not require the use of complex conceptual structures like conceptual metaphors (e.g. STATES/TIMES ARE LOCATIONS) for reflecting the link between spatial and abstract prepositional meanings. Rather, this link is accessed indirectly via event participants and settings. Engaging students in making meaning through semantic roles can be easier than learning prepositional polysemy through conceptual metaphors. The difficulty of dealing with such conceptual structures on the part of teachers and learners alike may be said to lie behind the unpopularity of the cognitive linguistic (CL) approach to teaching prepositions despite its proven effectiveness (as shown below).

The study is organised as follows. The semantics of prepositions from the perspective of Cognitive Linguistics is first sketched. Then, work on the application of the CL principles in teaching prepositions to EFL learners is reviewed showing that it is effective but unpopular. This is followed by proposing a cognitive-semiotic model for teaching the items to teacher trainees by bringing together prepositional polysemy and use through the TR-LM configurations and Radden and Dirven’s (2007) model of event schemas. The study ends with a summary of points and suggestions for further research.

2. The CL Approach to the Semantics of Prepositions: Space and Extension of Space

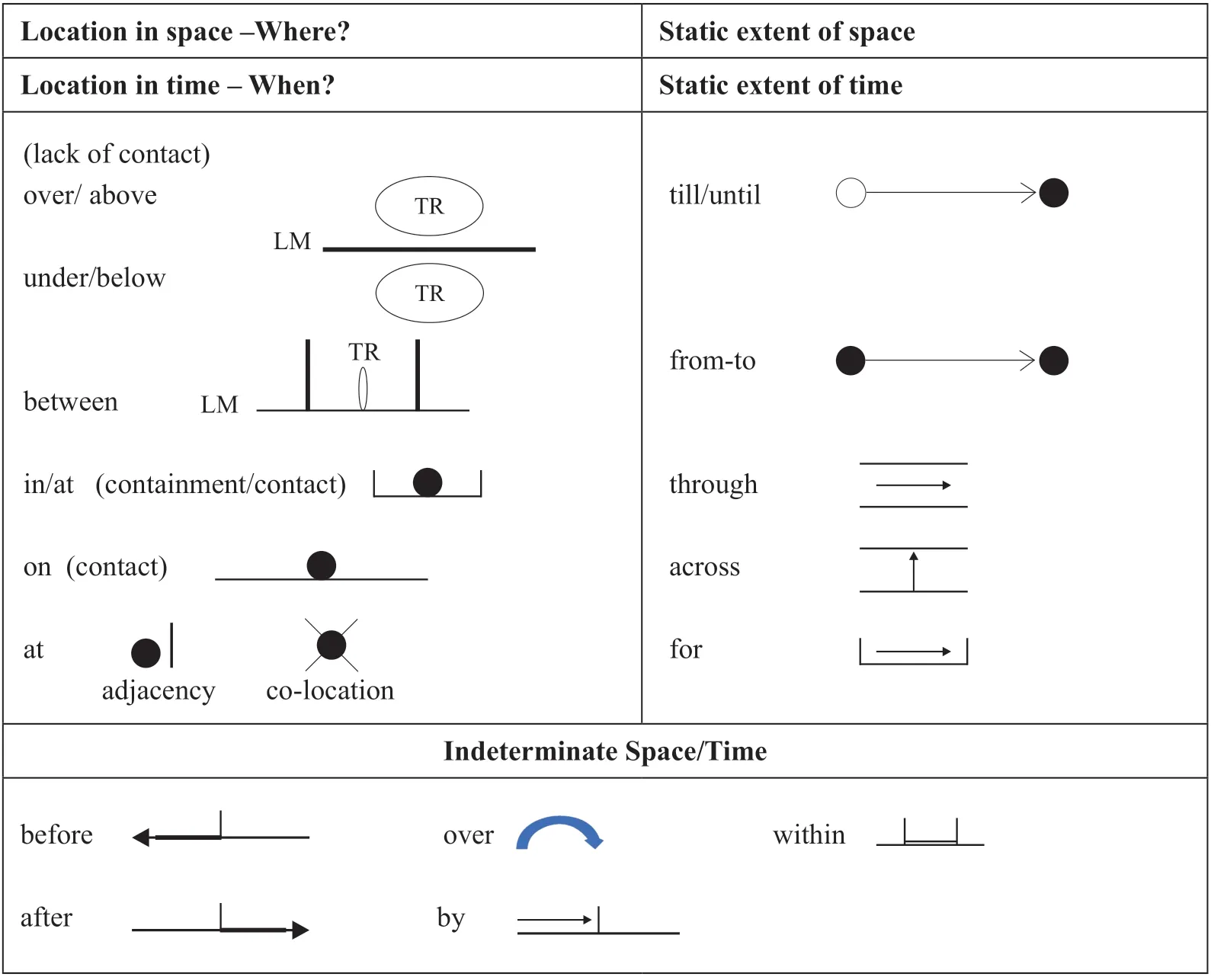

Understanding the CL analysis of prepositional polysemy is a prerequisite for understanding the CL approach to teaching the items. The analysis in question classifies prepositional polysemy into spatial, temporal and abstract meanings. The spatial meanings of prepositions are dealt with as designating primary, or proto, scenes in which a trajector (TR) is located in relation to a landmark (LM) (i.e. according to whether the TR and LM are perceived as co-located, close, far, etc.) (Tyler & Evans, 2003, 2005). Hence, a prepositional TR-LM spatial configuration is characterised by functional connections (or spatial-scene features such as “contact”, “support”, and “containment” that have been dealt with within the Lakoff and Johnson’s traditions as image schemas) as well as horizontal/vertical orientations or dimensions (measurable extent). The preposition on, for example, designates a spatial scene in which a trajector is in contact and supported by a line or surface (dimension) (Radden & Dirven, 2007; Talmy, 2000; Tyler & Evans, 2003). The lack of the functional features “support” and “containment” is expressed by orientational prepositions like above and below. Such prepositions designate spatial scenes in which the TR is either higher or lower than the LM, as in “My uncle lives above us and my aunt two floors below”. The same relation is designated by these prepositions even when a connection of contact between the TR and LM is suggested, as in “Life below water needs further exploration” and “He went over the bridge”. The prepositions below and over in these examples clearly profile downward and upward trajectories respectively (rather than contact).

Metaphorical extensions from the spatial meanings of prepositions express temporal and other abstract concepts in space-like ways (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980; Radden & Dirven, 2007; Rhee, 2004). Table 1 demonstrates the point by depicting LOCATION as the source concept (or domains of experience) in terms of which temporal and abstract extensions of the spatial prepositions in, on and at are structured. The conceptual metaphors TIMES ARE LOCATIONS and STATES ARE LOCATIONS are shown to reflect this structuring (see Lakoff & Johnson, 1980; Lakoff, 1987). The features of the spatial scenes designated by the prepositions are given in brackets. Note that the LM can be a container, a surface (or line) and a point, and that locations are fixed times (non-fixed times are specified by prepositions indicating a period (over the weekend) or a period combined with a time point (five minutes ago, in two weeks’ time, etc.).

Table 1. In, on and at across three domains of experience (adapted from Reda, 2017, p. 10)

Some prepositions like for and over designate location as the measured extent of a line length, as in “The road stretches for/over 100 miles”. Spatial extent is extended to temporal extent, or duration, in the sense that it is conceptualized as a static stretch of time (e.g. “I studied for ten hours”) (see Radden & Diven, 2007).

Spatial and temporal locations can also stand metonymically for dynamic scenes. Dynamic temporal scenes reflect a mental scanning of a period of time, as in “It rained from Friday to Saturday”. As for the dynamic location scenes, they involve the movement of a trajector along a path in a certain direction, a scene that is understood as subject to real-world force dynamics which is conceptualised in terms of the image schema SOURCE-PATH-GOAL. Dynamic instances of spatial extent, however, express fictive motion (e.g. The road goes from Leicester (up) to Coventry) (Talmy, 1988, 2000; Radden & Dirven, 2007). In such instances, the start and end point of the path (i.e. the source and goal) are in focus. When the focus is on one part of an event involving a source-path-goal orientation, either a static or a dynamic spatial scene may be designated. For example, depending on the context, on in a sentence like “She is on the bus” can refer to the static location of a trajector (while the bus is still stationary to the knowledge of the speaker) or it can trigger a metonymic scenario in which location stands for the directional movement of the trajector along a path. Static and dynamic locations can also converge. That is, it is possible to get directional readings for locative prepositions that designate one part of a spatial scene involving source-path-goal orientation, as the examples below demonstrate (after Gärdenfors, 2015, p. 13).

Source: (to come) from under, from behind

Path: (to pass) under, behind

Goal: (to go) under, behind

To move on to abstract space, Radden and Dirven (2007) showed that domains of abstract space are basically dynamic scenes that express the following notions in relation to a nuclear event: “circumstance”, “cause”, “reason” and “purpose”. This relation can be established at two different levels: physical reality as a cause and mental awareness of some other event as the reason or purpose, as the following examples demonstrate.

a. The winner jumped for joy. (= because of) [cause]

b. She lost her appetite for acute depression. (= on account of) [reason]

c. The hungry child was crying for food. (= in order to get) [purpose]

The same applies to domains of static abstract space in that they express psychological states caused by some factors, but the focus is on the resulting state rather than the cause. For example, the phrase in pain in “she is in pain” is the result of a certain cause. In this case, the participant in the subject position is an experiencer (rather than an agent).

“Circumstance” is a dynamic scene that may be tied to a place and/or time. This kind of relation is complex as it involves activating literal and figurative aspects of the SPACE domain. For example, “They were trapped in the traffic jam” can be interpreted as the cause of delay which involves temporal and spatial dimensions (Radden & Dirven, 2007).

Clearly, the CL approach to prepositions provides valuable insights into the semantics of the items. However, exploring the conceptual structures underlying prepositional meaning can make any learning task cognitively very demanding for students, considering their complexity, particularly for those who fall under the young or young adult age categories. Even teachers can find it hard to explain examples in terms of conceptual structures. The practice requires education and training and, as demonstrated in the section to follow, the CL principles are beyond the scope of standard textbooks and training concerned with English language teaching. These points might be important reasons why the CL approach to teaching prepositions (and vocabulary in general) did not gain a foothold in the English language teaching practice.

3. The Cognitive Linguistic Approach to Teaching Prepositions: Effective but Unpopular

Studies that applied the CL approach to prepositions measured the effectiveness of presenting prepositional polysemy as radiating out from spatial scenes. The findings of these studies are highly promising. For example, Boers and Demecheleer (1998) found that, in the context of a reading comprehension task, learners are more likely to guess the figurative meaning of a preposition like beyond if they have previously been presented with a definition of the spatial meaning (i.e. the one that implies some distance between the trajector and the landmark). Tyler, Mueller and Ho (2011) and Hung, Vien and Vu (2018) also demonstrated the effectiveness of introducing students to the polysemy of prepositions through explanations/visual demonstrations of the spatial meanings. Other linguists focused on teaching phrasal and prepositional verbs using conceptual structures. Boers (2000), for instance, used conceptual metaphors showing that structures like VISIBLE IS OUT AND UP and INVISIBLE IS IN AND DOWN are effective for teaching such verbs as find out, turn out, look up and show up. Similarly, Condon (2008) demonstrated how the use of image schemas for teaching the particles of phrasal verbs can clarify the meaning of verbs and facilitate their learning (see also the collection of studies in Boers & Lindstromberg, 2008; Boers, 2011).

However, despite the promising results, the CL insights into teaching prepositions do not seem to have gained popularity in the English classroom. As far as English teacher training programs are concerned, they focus on equipping trainees with techniques/activities for teaching prepositions in class, such as the following: “The classroom ghost: prepositions of place”, “Grand design: prepositions of place”, “Scavenger hunt: prepositions of movement”, “The list: prepositions of time and place” and “Timetable dictation: prepositions of time” (McLoughlin, 2016). Such activities might well be fun and engaging, but they are not based on any kind of CL analyses. They are simple opportunities for students to use prepositions for locating things, describing locations and movements, talking about scheduled events and so on.

Published literature and resources are certainly available for English language teachers who wish to incorporate CL principles into their practice of teaching prepositions (see the list below), but this would not be a standard practice at any educational level related to EFL.

Idioms organizer: Organized by metaphor, topic and key word (Wright, 1999)

Word power: Phrasal verbs and compounds (Rudzka-Ostyn, 2003)

Meanings and Metaphors: Activities to practise figurative language (Lazar, 2003)

Macmillan phrasal verbs plus (Rundell, 2005)

Cognitivism in EFL rests on constructivist views of education (see, for example, Piaget, 1970; Vygotsky, 1987) and does not incorporate CL principles. Take as an example the contents of standard ELT textbooks (see, for example, Hall, Smith & Wicaksono, 2011; Richards & Renandya, 2002). These textbooks present English teaching methodology as ranging from focusing on teaching grammatical patterns to adopting natural approaches that focus on active learning (see Figure 1). A methodology that requires the learner to go as far as exploring thought patterns underlying related linguistic concepts is beyond this range.

Figure 1. Popular ELT methodology

Moreover, the standard practice of teaching prepositions involves training students to use the prepositional phrases of time, place, movement, and so on. The contribution of the items to the formation of meaning at the sentence level is very vaguely presented in EFL/ESL teaching materials. The module on 7esl.com, for example, introduces prepositions as items that have the grammatical function of linking words together in a sentence. Prepositions are not simply linking words in grammatical structures. Rather, they play a vital role in the formation of meaning at the sentence level. Presenting this contribution to learners in terms of the TR-LM configurations and Radden and Dirven’s (2007) event schemas may help them understand prepositional meanings and uses in a systematic way. Radden and Dirven’s model also allows for adding a semiotic dimension to teaching prepositions from a CL perspective considering that learners need to add and drop semantic roles played by prepositions in order to talk about different world events.

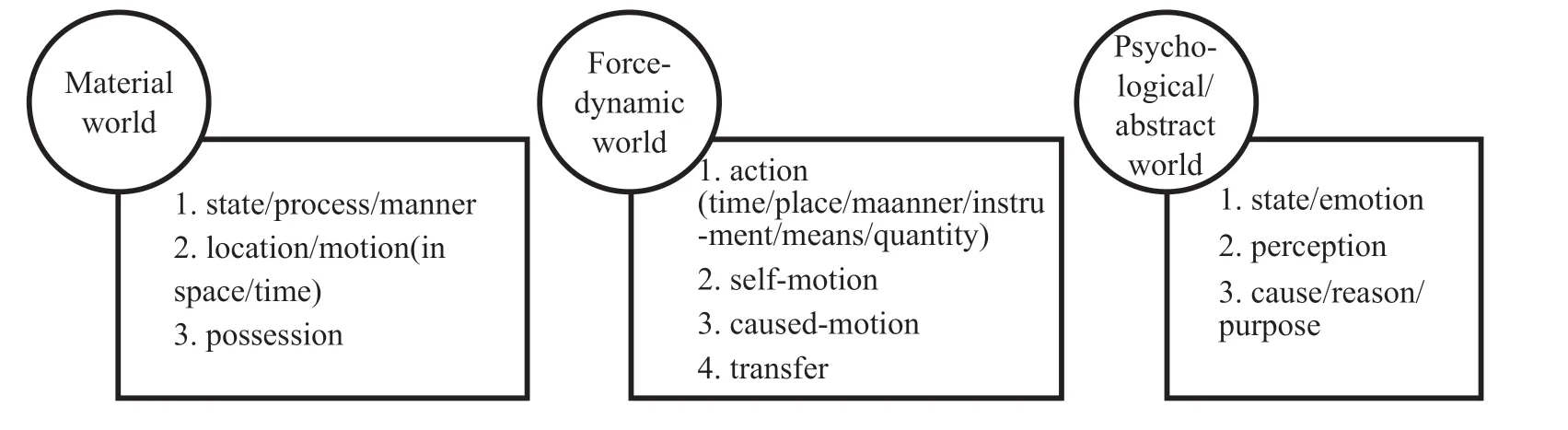

4. Radden and Dirven’s Event Schemas: A Carrier Model for Teaching Prepositions from a Cognitive-Semiotic Perspective

Radden and Dirven’s (2007) approach to grammar treats grammatical constructions as forming conceptual cores that reflect our categorisation of the world as things and relations. THINGS are designated by nouns, whereas RELATIONS are designated by the other lexical classes (verbs, adjectives, prepositions, and so on). The different assembly patterns of these categories are event schemas belonging to three worlds: the material, psychological and force-dynamic worlds. Table 2 presents a survey of event schemas and their different role configurations (THEME (T), LOCATION (L), GOAL (G), POSSESSOR (P), EXPERIENCER (E), CAUSE (C), AGENT (A), and RECIPIENT (R)). Event schemas are demonstrated by examples in which meaning is made with prepositional constructions.

Table 2. Survey of event schemas and their role configurations (adapted from Radden & Dirven, 2007, p. 298)

Note that prepositional constructions have a semantic role to play in each event schema. They can be the THEME, LOCATION, GOAL, CAUSE, TARGET or RECIPIENT. An examination of these roles in light of Rhee’s (2004) representation of the semantic structure of prepositions (Figure 2 below) will show that the semantic roles that prepositions can play in event schemas cover their polysemy. Prepositional constructions assemble with other constructions to designate location and physical or psychological motion. They can also attach to all event schemas to play the nonparticipatory role of defining the temporal event setting. All this perfectly matches the polysemy of the items.

Figure 2. The semantic structure of prepositions (Rhee, 2004, p. 415)

Another point that can be abstracted from comparing Table 2 and Figure 2 is that event schemas and prepositional polysemy are TR-LM static/dynamic configurations and can, therefore, be presented through the same configurations.

5. The Proposed Model

The model proposed for teaching prepositions is a three-hour grammar module with the following structure:

1. an introductory session in which prepositional meanings are viewed as TR-LM configurations;

2. a main session in which prepositional constructions as TR-LM configurations are dealt with as the building blocks of event schemas;

3. a final session in which prepositional constructions are dealt with as adjuncts defining event settings. The session closes with a recap.

5.1 Prepositions as TR-LM configurations

This session introduces the polysemy of prepositions through visual representations. Features like “adjacency”, “contact”, “lack of contact”, “containment”, “co-location”, “betweenness”, and so on are the concepts to be used for describing represented meanings. The teacher trainer opens the session with an introduction to prepositions like over and on as TR-LM spatial configurations. He/she then represents the spatial scenes designated by the prepositions and describes them in terms of the contrasting features “contact” and “lack of contact”. Another activity is representing the meanings of at in the following examples as different TR-LM spatial configurations: “at the door”, “at the supermarket” and “at the crossroad”. The three different spatial scenes can be described in terms of features like “adjacency/lack of contact”, “containment/contact” and “co-location/contact” respectively (the representations in Figure 3 are for teacher trainers to use). A possible follow-up activity is for the trainer to divide trainees into groups and then give each group a pair of the following prepositions, for example, to represent as different scenes of “betweenness”: between, among, within, through, along and across. On finishing the activity, students share their representations and discuss them aloud. Suggestions that can improve the represented TR-LM spatial configurations should be encouraged and examined carefully.

The second part of the session focuses on prepositional uses suggesting physical motion. The trainer starts by representing the scenes designated by up and down, for example, in an instance like “He walked up/down the road”. Motion/orientation can be represented by an arrow. The different dynamic scenes need to be described in terms of the contrasting features “high-low” and “front-back” considering that the use of up and down can be literal or can indicate movement on the part of the TR away from or towards (facing) the LM. Trainees can then be prompted to give examples and provide visual representations for the spatial scenes in their examples. A list of prepositions needs to be distributed to students at the beginning of such an activity for them to choose from. An activity like this can yield interestingly different TR-LM configurations since dynamic spatial scenes vary according to the event depicted.

Correspondences between space/motion and time can now be focused on with Figure 3 below projected on the board. Examples of prepositional uses reflecting the correspondences in question (e.g. “on medication”, “on the way”, etc.) can be found in Schneider, Srikumar, Hwang and Palmer (2015, p. 117). An important point to be mentioned to students at this point is the difference between fixed and non-fixed (or relative) time and how this difference is reflected in our selection of prepositions. The feature “betweenness” can be used for representing duration and relative time, and a point or line for fixed time and extent. The activity sheet in Appendix A is for practicing the correspondences in class or as homework.

Figure 3. Prepositional scenes (adapted from Radden & Dirven, 2007)

This session is very important, particularly if presented in such a way as to show learners that spatial scenes are real-life scenes of space, time and movement, and that the use of prepositions should aim at reflecting the exact features of the scenes we want to describe. A good way to end the session is through drag-and-drop and matching activities engaging students in identifying the features of prepositional scenes and the multiple ways of viewing a scene (i.e. its polysemy).

5.2 Prepositional constructions as event participants

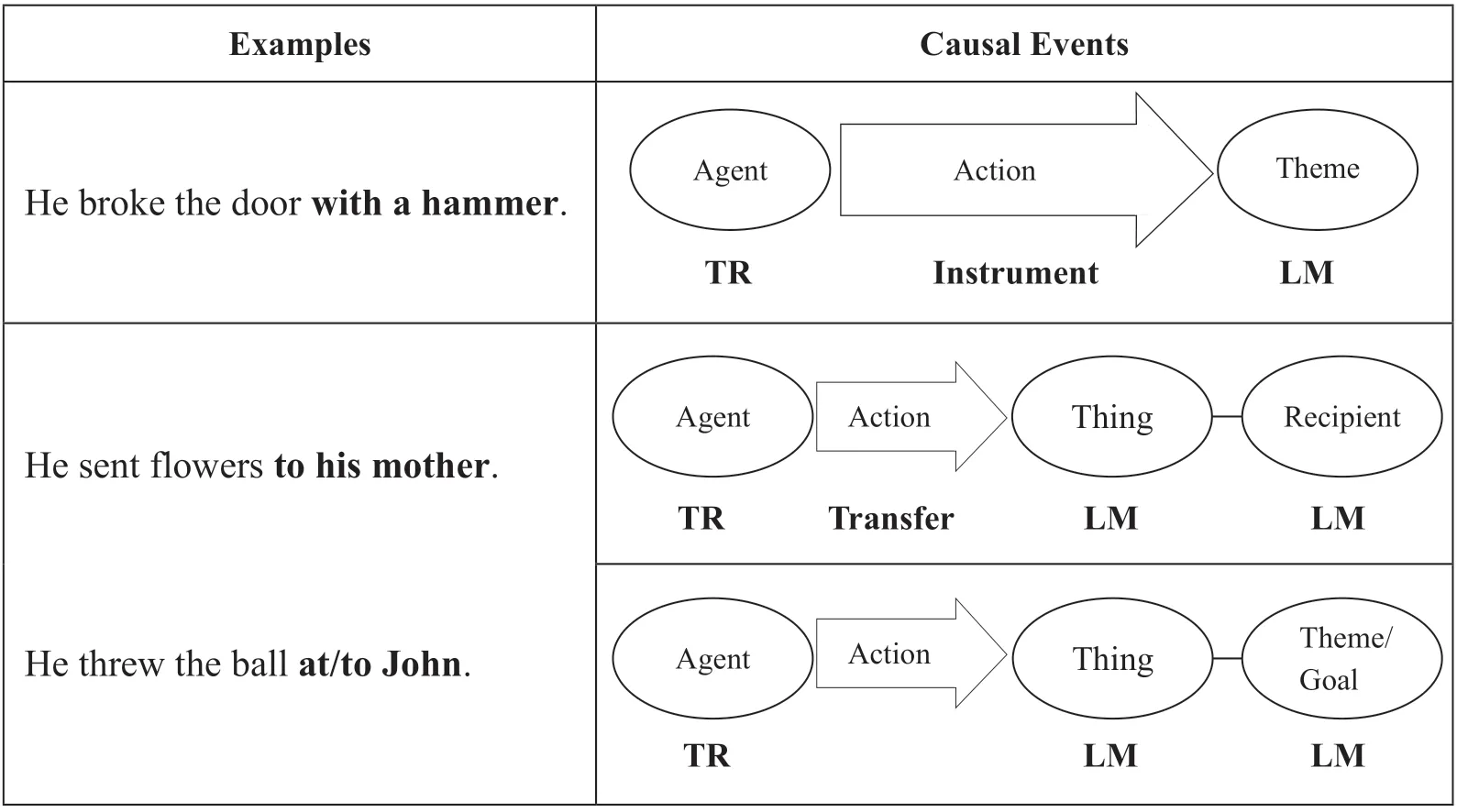

This session introduces propositional constructions through their participatory roles in event schemas. The TR-LM spatial configuration is the basis on which all event schemas are to be built. Force-dynamic world event schemas are the best schemas for starting the session as it can demonstrate three semantic roles that are played by prepositional constructions in event schemas. The point can be presented with the aid of Figure 4.

Figure 4. A demonstration of some semantic roles played by prepositional constructions in causal events (adapted from Langacker, 1987).

The manipulation of the TR-LM organisation can be shown through the passive construction whereby the prepositional construction in the LM slot is the agent that acts on the entity in the TR slot (the theme) (e.g. “The cat was rescued by a Samaritan”).

Material and psychological world events can then be introduced as schemas that involve not only manipulating the TR-LM spatial configurations of force-dynamic world event schemas, but also backgrounding the whole action and foregrounding its effect. The most important schemas to focus on are those in which a prepositional construction establishes an atemporal or a temporal relation between the affected entity (the theme in the TR slot) and the resulting effect (the state/process in the LM slot). The points can be demonstrated by the sentences “The bus is in the station” and “The meat is on the turn” showing that they are scenarios in which the actual acts (driving and cooking) are backgrounded, but the effect of each is foregrounded as a state or process. The scenarios are built through propositional constructions designating location and motion. The presentation of these points can be aided by Figure 5 drawing attention to the manipulation of TR-LM organisation.

Figure 5. Temporal and atemporal events instantiated by grammatical events (adapted from Langacker, 1987, p. 220; 2002, p. 211).

A follow up activity would involve asking trainees to use prepositional constructions to build psychological/abstract world event schemas based on the scenarios in Figure 5. The trainer can start with examples like “She is in love”, “She is going through bad times” and “She is in full awareness of her responsibilities”, drawing attention to the role EXPERIENCER.

After explaining the above-mentioned points, Table 2 above, which includes a survey of event schemas and examples containing prepositions, can be projected on the board for discussion and further examples. The trainees should be asked to deconstruct event schemas and reconstruct them through prepositional phrases that play different roles in the schemas. In addition, to see the correspondences between the semantic structures of prepositions and event schemas, students’ attention should be directed to the static-dynamic continuum of meaning that can be constructed through prepositional constructions in event schemas.

Practice exercises need to be given after presenting the above points. Some examples are drag-and-drop activities requiring the trainees to identify the semantic roles of prepositional constructions and to build event schemas by adding prepositional constructions to some strings of words. The activity can also be given as homework.

5.3 Prepositional constructions as adjuncts

This session opens with a revision of the module and feedback on students’ activity attempts. Prepositional constructions can then be shown to have the potential to attach to any event schema as adjuncts that define settings like “time” (e.g. “He arrived at 8:00”) or “manner” (e.g. “He travelled by taxi”). Their role as subordinators in complex sentences (i.e. as adjuncts expressing meanings like “cause”, “reason” and “purpose”) can be introduced as an extension of the semantic role CAUSE (e.g.“She is jumping for joy”) through examples like “He opened the door in order to get fresh air”, and “she found the door open as she entered the building”.

The session can be closed with a recap activity. A possible activity is to project Figure 6 on the board and get students to write examples for the relations expressed by prepositions in world event schemas. Students’ attention needs to be drawn to the addition of the description “abstract” to psychological world events, noting that this is done for fitting their role as subordinating conjunctions in event schemas.

Figure 6. Relations expressed by prepositions in event schemas belonging to the three worlds of experience

At the end of the module, drag-and-drop and matching activities can be given to the trainees to practice all the points examined in the three sessions, from prepositional scenes to event schemas. The activity can be done in class or at home.

6. Conclusion

This paper proposed a cognitive-semiotic model for teaching English prepositions to English teacher trainees. The model links prepositional polysemy and use through the concept of TR-LM configurations and Radden and Dirven’s (2007) event schemas. The schemas were not only chosen on the basis of their correspondence with prepositions in terms of semantic structure, but also because they provide opportunities for learning prepositions through meaning making activities. The different event schemas can be built through different semantic roles and prepositional constructions can assume all participatory and non-participatory roles configuring event schemas. It is argued that the proposed model can help English teacher trainees to learn the polysemy and use of prepositions in a systematically graded manner, a manner through which teacher trainees can learn to prepare conceptually-linked, graded materials for teaching prepositions to EFL learners. However, research is needed to test the argument. The study limited itself to designing a module for applying the model.

Language and Semiotic Studies2020年4期

Language and Semiotic Studies2020年4期

- Language and Semiotic Studies的其它文章

- Investigating Disfluencies in E-C Sight Translation

- The Pragmatics of the Rhetorical Question in Selected (English) Qur’an Chapters

- Rhetorical Questions in Wen Xin Diao Long: An Enthymematic Analysis

- Multileveled Engagement: A Cognitive Empirical Approach to Crossover Picturebooks

- #Take Responsibility: Non-Verbal Modes as Discursive Strategies in Managing Covid-19 Public Health Crisis

- Miao Folk Music and the Marginal Modernism of Shen Congwen