Multileveled Engagement: A Cognitive Empirical Approach to Crossover Picturebooks

Xiaofei Shi

Soochow University, China

Abstract Crossover picturebooks attract readers of different ages. The trend of refocusing on the body in children’s literature criticism, especially under the influence of literary cognitive studies as Maria Nikolajeva points out (2016), provides a context to reconfigure our understanding of crossover picturebooks. Informed by literary cognitive studies, particularly the theory of brain laterality, the project selects the picturebook that may have crossover potential to start with, then investigates the actual readers’ engagement with the potentially crossover picturebook, and finally feeds the insights gleaned from the empirical study back into the understanding of the selected text, and possibly crossover picturebooks generally. The project aims to learn about the crossover picturebook through exploring how it impacts readers. It was a small-scale case study, conducted in the east of England, UK. Colin Thompson’s How to Live Forever was used with two adults and two children. Observation and interviewing were used to collect data. Text-related creative activities served to support or clarify the oral response. The project reveals: the multileveled nature of crossover picturebooks that many scholars emphasize may correspond to the multileveled engagement that texts can elicit from readers, which is partially the outcome of cognitive-affective skills and mechanisms engaged differently across children and adults. This study also shows the crossover potential particular to picturebooks: picturebooks may use the visual to flesh out the embodied experience, which can springboard further thinking about abstract, complicated notions. This mode of representation corresponds to the way the human mind works, thus engaging children and adults alike.

Keywords: crossover picturebook, cognitive literary studies, empirical research

1. Introduction

Crossover in children’s literature criticism refers to the phenomenon when a text appeals to readers of a wide age range (Beckett, 2009, 2012; Falconer, 2009). Since the “landmark” Harry Potter series as Sandra Beckett labels it (2009, pp. 1-2), the recent years have seen a rise in the production of and research on crossover literature. The existing research has focused on crossover fiction (e.g. Beckett, 2009; Falconer, 2009) and crossover picturebooks (e.g. Beckett, 2012; Ommundsen, 2014). This article discusses crossover picturebooks because how picturebooks, traditionally connected with children, may attract both children and adults makes an especially interesting line of enquiry, though some issues wrestled with in this study may be relevant to crossover literature in a broader sense. The view of picturebooks as children’s prerogative has been put to question (Scott, 1999; Desmet, 2004; Beckett, 2012; Salisbury & Styles, 2012). Changes in picturebook tradition, especially in the Nordic countries, even result in picturebooks aimed at adults (Ommundsen, 2014). Therefore, the changes in picturebook production also call for the research on crossover picturebooks.

The issue that concerns many researchers is what kind of picturebooks is crossover. Beckett (2012) defines crossover picturebooks as “multileveled works that are suitable for all ages” (p. 16). Åse Marie Ommundsen argues that crossover picturebooks are the picturebooks that evoke an implied child reader and an implied adult reader (2014, p. 72). Ommundsen bases her definition on Wolfgang Iser’s notion of the implied reader, which is the reader constructed by and inscribed in the text rather than the flesh-and-blood person that approaches the text (Iser, 1974). Mieke Desmet suggests that the naïve dimension of the Taiwanese picturebook creator Jimmy Liao’s works may attract a child audience and their complex and “highly allusive” dimension may appeal more to an adult audience (2004, p. 71). She seems to treat adults’ way of reading as superior to children’s (p. 77). Without working with real readers, the abovementioned scholars focus on crossover more as the affordances of the text, that is, how the text may have the potential to attract readers of different ages. Moreover, embedded in their attempts to delineate crossover picturebooks is the issue of how the child is conceived in relation to the adult.

Karín Lesnik-Oberstein emphasises the constructedness of the concept of the child (2011, pp. 1-17). Richard Mills reviews various perspectives on the constructed child, such as the child as innocent, vulnerable and so on, situating the perspectives within the relevant sociocultural contexts (2000). In response to the perception of the child as a social construction, children’s literature research has shown a material turn, refocusing on “the physicality of children’s bodies”, as Maria Nikolajeva observes (2016, p. 132). The trend of returning to physicality is reflected in a growing body of research that draws on cognitive literary studies, for instance, Nikolajeva’s Reading for Learning (2014) and the issue 6.2 of the journal International Research in Children’s Literature (2013) published by Edinburgh University Press. The concept of crossover literature is established based on mixed audiences it can attract, which are separated into different age groups. The age difference inevitably causes the difference in the body. Even when explaining the constructedness of the child, Mills recognises that children are distinct from adults in cognition (2000, p. 23), and human cognition relies on the material existence of the body. The trend of refocusing on the body in children’s literature criticism, especially under the influence of literary cognitive studies, provides a context to reconfigure our understanding of crossover literature.

Literary cognitive studies, referring to experimental psychology, neuroscience and brain research, provide a cross-disciplinary approach to the issues of reading, literacy and literature (Stockwell, 2002, pp. 1-11). The brain is the cognitive-affective structure that, developing with age, grounds the way readers engage with fictional narratives and in general, the world. The brain encodes its history as a dynamic system, with the evolutionarily newer layer atop the older one (Crago, 2014, pp. 7-8). The evolutionarily most recent layer is the cerebral cortex, which is divided into the right hemisphere and the left hemisphere. The bihemispheric structure gives rise to two fundamentally different ways of seeing and experiencing the world. Human beings’ interaction with the world is synthesised from the workings of the two hemispheres that cooperate but more often conflict with each other (McGilchrist, 2012; Panksepp & Biven, 2012; Crago, 2014). Hugh Crago (2014) suggests that the development of the capacity for understanding fiction from infancy to old age relates to the continual changes in the brain. The theory of brain laterality connects the readers’ engagement with the text to the cognitive-affective structure of the brain. Such a connection is plausible because what human beings encounter in the world is delivered to and mediated through the brain, which ultimately sends the encounter back to the world. Though it is arguable whether readers at a certain age may prefer a particular type of story, as Crago claims, his study offers a perspective on exploring the child-adult reader differences as spread on a broad spectrum rather than in two binary categories. This perspective helps to take into account a wide range of readers of crossover literature that cannot be distinctly categorised as the adult or the child.

Connecting the age difference to the difference in cognitive-affective skills and mechanisms does not mean returning to essentialism. As Nikolajeva argues, “This trend [of refocusing on physicality] does not signal a return to essentialism but reflects the complexity, plurality, and ambiguity of our understanding of childhood” (2016, p. 132). Moreover, the investigation of the cognitive-affective skills and mechanisms that presuppose fiction reading allows for the consideration of sociocultural factors. For instance, Nikolajeva suggests that readers draw on their real-life experience to understand fiction, including the experience of interpersonal relationships (2014, p. 16), which is subject to the influence of the sociocultural environment one is situated in.

Despite the ongoing changes and possible individual differences, some cognitive functions remain qualitatively alike throughout various life stages and across human beings. For instance, the right hemisphere of the brain plays a dominant role in broad and flexible attention, while the world of the left hemisphere is more local and narrowly focused (McGilchrist, 2012, pp. 39-40). Anything new must first be directed to the right hemisphere before coming into focus for the left. Therefore, the right hemisphere is more engaged than the left in apprehending anything new, both verbal and visual (p. 40). The primacy of the right hemisphere in attending to the new forms part of the fundamental human existence. This accounts for scholars’ observation (e.g. Wolf, 2012, pp. 3-6; Nikolajeva, 2014, p. 27) that human beings, both child and adult, are by nature capable of engaging with an inventive fictional world very different from what they are used to in real life. The relative stability of some cognitive functions also provides evidence for the claim of crossover scholars, such as Maija-Liisa Harju (2009, pp. 365-366), Carole Scott (1999, p. 102) and Deborah Thacker (2000, p. 1), that a continuum of understanding and experience exists throughout various life stages.

Literary cognitive studies explore not only textual affordances, but also how readers engage with texts. Aside from Beckett’s, Ommundsen’s, and Desmet’s accounts of the textual affordances of crossover, the other aspect is how actual readers engage with the text that may attract a wide range of readers. Adults are often seen as parents in shared picturebook readings rather than as readers on their own. The presumptions of adult picturebook readers not supported by empirical evidence may wrongly inform the way crossover picturebooks are conceived. Thus, an empirical study of actual child and adult readers is especially beneficial for exploring crossover picturebooks. Evelyn Arizpe and Morag Styles include literary cognitive studies in the newly emerging analytical tools and theoretical frameworks that have a huge potential for picturebook research (2016/2003, p. 143). Though empirical research of picturebooks has not yet largely applied cognitive literary studies, this theoretical perspective has informed research with actual young readers. For instance, Marie-Laure Ryan (2003), using the novella Chronicle of a Death Foretold with high school students, explores how the readers’ construction of narrative space is subject to the workings of cognitive mechanism, such as short-term memory. Ryan’s project shows the potential of literary cognitive studies for guiding and structuring empirical research.

However, as Peter Stockwell suggests, literary cognitive studies fundamentally are a new way of thinking about literature (2002, pp. 1-11). Karen Coats (2013) provides an example of how to learn about texts through exploring the way they affect readers. She proposes to understand children’s poetry in terms of how it creates “a holding environment in language to help children manage their sensory environments, map and regulate their neurological functions, and contain their existential anxieties” (p. 140). The theoretical perspective of literary cognitive studies therefore offers a way to integrate the textual affordances of crossover with the actual readers’ responses to the textual affordances: examining the actual readers’ engagement is to shed new light on the texts. Rachel Falconer even contends that we can only arrive at a more comprehensive understanding of crossover literature through exploring what it does for readers (2009, p. 27).

Informed by the perspective of literary cognitive studies, the project selects the picturebook that may have crossover potential to start with, then investigates the actual readers’ engagement with the potentially crossover picturebook, and finally feeds the insights gleaned from the empirical study back into the understanding of the selected text, and possibly crossover picturebooks in general. The selection and analysis of the primary text is guided by the existing studies of crossover picturebooks and the theory of brain laterality. The empirical part seeks to address the two questions: (1) How do the actual child and adult readers engage with the potentially crossover picturebook? (2) What can we learn about the selected picturebook as a crossover text and possibly crossover picturebooks generally in the light of the actual readers’ engagement?

2. Selecting and Analyzing the Picturebook

Colin Thompson is often mentioned in crossover studies (e.g. Scott, 1999). Nikolajeva and Scott point out that the abundance of pictorial details evoking rich connections is Thompson’s trademark (2006, p. 239). The representation of the fictional world epitomises Thompson’s unique style. Scott illustrates with the fictional world in Thompson’s Looking for Atlantis to explain how the dual narrative of picturebooks enhances crossover potential (1999, pp. 99-110). The construction of the fictional world is also a research focus in literary cognitive studies (Nikolajeva, 2014, pp. 21-47). This study uses Thompson’s less explored picturebook—How to Live Forever (1995), henceforth Forever. The focus of the text analysis is on the fictional world, and correspondingly, how the actual readers engage with the fictional world represented in Forever will be the focus in the empirical part.

In Forever, Peter finds a record card of the book called “How to Live Forever”, but the book is missing from the shelf where it should have been. Determining to find it so that he will not grow old, Peter starts to look for the book. He meets four old men in an attic, and the men lead him to the ancient child, who has read the book “How to Live Forever,” and is forever frozen in time. After talking to the ancient child, Peter relinquishes the idea of reading the book and living forever.

Forever represents a fictional world inventive in the fundamental ontological aspect. In the picturebook, a series of worlds is interlocked. These worlds can be divided into two main types. The first type is the mundane world. The second type is the miniature world of magic, such as the interior of the library populated by miniature creatures living in the books and under the floorboards. By embedding lighted doors and windows in the grand mundane world, the visual hints at the magical miniature worlds underneath. The multitudinous worlds are tightly packed with enigmatic visual details. Eyes peek out from behind the shelves, limbs seem to be alive on their own, and dilapidated odds and ends are lying around at every corner. The fictional world challenges the law of time readers are used to in the real world, as time forever freezes in the ancient child. As aforementioned, since the right hemisphere of the brain is naturally tuned to the new and unfamiliar, child and adult readers should be able to engage with the inventive fictional world represented in Forever.

The multitudinous worlds show a string of changes. The interior of the book on the tenth spread is compartmentalised into lacquered shelves. The tight compartmentalisation creates an effect of fragmentation and restriction, resulting in the inability to see a larger picture. On the twelfth spread, the Chinese garden is depicted in regular blue and white patterns. Peter is the only colourful spot against the huge cold background. The picture counterpoints the verbal “bright butterflies” (my emphasis). The regular geometric shapes and cold colours give an unpleasant sense of stagnation. The fifteenth spread depicts a garden of lighted windows, flowing water, green trees, and a bright butterfly, implying a restoration of life. The pattern of the changes in the multitudinous worlds parallels the theme of the picturebook—going through immortality, Peter discovers that immortality equals death as immortality means a stagnant state of existence that does not lead anywhere, and decides to move forward with life, in another sense, to inevitable mortality. The picturebook subtly incorporates and compares two ways of seeing and experiencing the world—the right hemisphere encourages us to connect to the world around us with its “changeability”, “impermanence”, and “interconnectedness”, while the left hemisphere enables us to make sense of the world through fragmenting and stabilising it (McGilchrist, 2012, p. 93). The way the fictional world is represented therefore has crossover potential because it is grounded in human beings’ existential conditions, that is, the conflict and cooperation of the right hemisphere and the left.

The fictional world represented in Forever may engage readers’ attention and imagination and stimulate their cognitive activity. Readers of a wide age range can engage with the inventive fictional world because the right hemisphere of the brain is tuned to the new and unfamiliar. The way of representing the multitudinous worlds is grounded in the fundamental human existential conditions.

3. Method

3.1 Sampling

The project was a small-scale case study, conducted in the east of England, UK. The brief information of the participants is as follows:

Lucy (female, 9 years old)

Lucy is from Ireland, and was studying in a local primary school at the site of research. She was well read.

Oliver (male, 8 years old)

Oliver, from Ireland, was studying at the same primary school. He said that he was not a big fan of reading, and when he read, he preferred comic books.

Rihanna (female, 24 years old)

Rihanna is American, and was studying at the site of research for one year. She was doing a Master’s degree, which had nothing to do with children’s literature.

Sophie (female, 30 years old)

Sophie is Chinese, and was studying at the doctoral level at the site of research. Her research was not relevant to children’s literature.

The particularities of the participants were largely the result of convenience sampling. Convenience sampling does not aim for the sample’s representativeness of a larger population, and enables the researcher to pool together limited resources within reach (Cohen et al., 2011, pp. 155-156). Since this project was an exploratory study of a new way of thinking about crossover picturebooks through investigating the actual readers’ engagement, the generalisability of specific conclusions regarding the set of sampled readers was not of primary concern. The particularities of the participants, on the one hand, posed a challenge to the researcher in singling out age and cognitive function as specific factors for the analysis later. On the other hand, if the patterns of difference between the adults’ reading and the children’s could be identified despite their particularities, this rather lent support to an interpretation isolating the factors of age and cognitive function.

3.2 Data collection

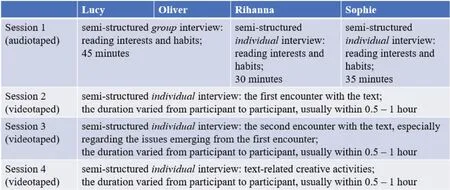

For each participant, there were in total four sessions of interview. An overview of the sessions is as follows:

Table 1. Overview of the sessions

The semi-structured interview with its “flexibility” allows the participant to “develop ideas and speak more widely on the issues raised by the researcher” (Denscombe, 2010, p. 175), and the researcher to probe into the given response (Cohen et al., 2011, p. 420). The semi-structured interview therefore was adopted in all the interviewing sessions. The first session with the participants was not to discuss the selected text, but to know more about their reading interests and habits. Group interviewing was used with the children because children may feel less uncomfortable in the presence of a stranger when they are talking in a group (Greig & Taylor, 1999, p. 132). Individual interviewing was used with the adults. The second session of individual interview centred on the readers’ encounter with the selected picturebook. The participants were not told beforehand which picturebook they would read because their spontaneous reaction was of more interest. The third session of follow-up individual interview was designed to address the issues that emerged from the second session. The fourth session was to further probe the readers’ responses to the text in the form of textrelated creative activities, for instance, drawing or creative writing of their own choice. The main purpose of the creative activities was to support or clarify the oral responses.

Several interview prompts were prepared for the first and the second sessions (see Appendix A and B for the interview prompts of the first two sessions respectively). During the interviews, the sequence and exact wording of the prompts did not have to be strictly followed. The interview prompts had been tested in a pilot study prior to the project. The sessions two to four were videotaped, while the first one was audiotaped for the concern that the participants might get intimidated to be videotaped the first time we met. The sessions were conducted in a relatively informal setting, as the project was about the readers’ spontaneous engagement rather than their instructed responses.

3.3 Data analysis

The data included the audiotapes and videotapes, a full transcription of the videotapes, and the products of the text-related creative activities. The data was first examined in terms of what textual aspects the readers engaged with. The pieces of data relating to the readers’ engagement with the fictional world were then selected out for further analysis. The data analysis consists in the individual accounts of the readers’ engagement that explore the salient features and patterns of their readings. The discussion is placed at the end of the article to explore what patterns of differences and similarities emerge across the four readers, and see how the findings may inform the understanding of the selected text and possibly crossover picturebooks in general.

4. Findings

4.1 Lucy

In the first reading, when I asked Lucy to choose one page and tell me about what she thought of it, she opted to stay at the third spread that presents a panoramic view of the bookshelf world. She spent half of the first reading describing how the bookshelf world looked like a home to her and later produced a piece of writing about it. In the second reading, she acted out the idea that the bookshelf was a home:

L: And maybe they can live all up inside the whole shelf, oh ~ [clapping]. Ba, ba, ba, ba, ba [laughing, and emulating how a person goes up]. It could be like a block of

apartments, like there’s a room there, a room there, a room there, and a room there [using her finger to point at the books all the way up the shelf]. And somebody may live in the ceiling, between the ceiling and the floor, there’s a book, pull it out [pretending to pull something down from the ceiling], that would be so cool [laughing and waving her hand in a big circle]! It would be awesome to live in a shelf, like “nice book over here, yeah, um ~ sounds good” [laughing and pretending to snatch a book and read]. Snatch, Snatch [laughing and pretending to make great efforts in order to snatch something out of her reach]. It’s great! And then you’ve got a front door and a back door. In the front door, out the back door, go there, so like bye bye Amanda, hello Samantha [laughing]!

Researcher: Oh, that’s wonderful!

L: Oh ~ Yeah! And then we can have something like “-anda,” like something, so like, like, I have to think about this, like, bye bye Amanda, hello Samantha, hello Lyanda [laughing], and then hello somebody else, up, hello, hello, up, hello neighbors, up, hello neighbors [using her finger to point out on the page the route upstairs]. Like, hello best friend, like go inside, whoo~ [using her finger to point all the way up the shelf], hi, best friend. Living in the ceiling, they have a great view over the city. She showed a bustling bookshelf world, where miniature people live all the way up, winding their ways around, greeting friends and neighbours, and snatching books as they climb up. Her performance incorporated pointing, gesturing, shifting body postures, and laughing.

Her performance was also rhythmic, resembling poetry in its primitive form. The rhythmic bits in her performance can be grouped as follows:

ba/ ba/ ba/ ba/ ba

a room there/ a room there/ a room there/ and a room there

snatch/ snatch

in the front door/ out the back door

bye bye Amanda/ hello Samantha/ hello Lyanda

Iain McGilchrist sees music as preceding language rather than as an incidental spinoff from language, because the musical aspects of language (such as intonation, pitch, rhythm, and so on) come first in children before syntax and vocabulary (2012, pp. 103-104). This resonates with Crago’s finding that children, as young as under two years old, experiment with baby talk of a musical nature. The meaning of baby talk depends not so much on the words that are used as on the embedded sound patterns. When experimenting with sound patterns, young children are conveying an underlying emotional concern (Crago, 2014, pp. 15-17). McGilchrist goes further to argue that music is the “communication of emotion”: “the prosody and rhythmic motion … emerge intuitively from entrainment of the body in emotional expression” (2012, p. 103). The musical aspects of Lucy’s performance were anchored in her embodied experience, as she climbed upwards, propped the body with clawing hands, occasionally spared one hand to snatch a book, and waved to friends when she scrambled up. The embodied experience was replete with emotions—joy at seeing and greeting friends, relief and pleasure at taking in a whole view of the city when she finally arrived at the top, and most importantly, the ecstasy of living through a fictional world. Her performance epitomised what McGilchrist views as the fundamental interconnectedness of embodiedness, musicality, and emotion.

4.2 Oliver

When reading Forever for the first time, Oliver sensed the existence of another space beyond the bookshelf world from the pictorial detail of the spaceship taking off:

O: that’s kind of like stopping people who’re living in the space from going there, they’re stopping at this atmosphere, and they’re seeking another atmosphere.

Researcher: So you mean there’s something different out there?

O: Yeah. Because this background, this space, these astronaut things, like the astronaut living.

The dialogue revealed Oliver’s view of the bookshelf world: first, the bookshelf constituted a living space; second, the bookshelf was confining as its inhabitants were stopped from “going there.”

Compared to Lucy, who seemed to view the bookshelf world in a positive light as manifest in her response “my dream bookshelves,” Oliver tended to take a negative stance. Oliver’s negative stance towards the bookshelf world paralleled his earlier idea that it was confining. When I invited him to picture what it would be like to live in a world of books, Oliver acted out the danger the inhabitants of the bookshelf would face if they were discovered:

No, [“no” meaning “I don’t want to live in the bookshelf world”]. Because if somebody comes to borrow it [a book], they open it up, and there will just be rooms in it. That would actually be pretty weird [laughing]. You can just pick people up by their hair [putting his hand on top of the head, and lifting his own hair up], and they’re like “don’t lift me up” [squinting up and laughing]! But they still lift them up, and they’re so frightened, and they try to run away.

Oliver tried out the perspective of those who live in books, squinting around as if to see who was lifting him up, and exclaiming “don’t lift me up!” It can be inferred from his peals of laughter that Oliver very likely had fun with acting out the scene of a person being pulled up by his hair and uprooted out of his home, which however would be frightening in real life. As Susan Keen suggests, the trying out of different perspectives and feelings in literary reading occurs in a safe zone without putting a resultant demand on readers’ action in real life (2007, p. 4). Oliver’s performance was circumscribed within the safe zone—he could imagine and act out the danger in the fictional world without jeopardising his own security.

4.3 Rihanna

It fascinated Rihanna to see the pictorial representation of books as a physical space. She was amazed at how “each book is a house”. She traced the changes in the position and layout of the books, and then moved from the materiality of books foregrounded in the visual to a more abstract notion of books as carriers of life stories and information: “It makes sense, because if you read a book, it’s a story about somebody else’s life. It’s almost like where they live. So it’s almost metaphorical.” For her, the multilayered visual details crowding the bookshelf could generate the same effect on senses as the “massive”, “overwhelming” amount of information that a book contains.Another salient feature of Rihanna’s engagement with the fictional world was that she made efforts to trace and explain the consistent appearances of the small visual details that do not contribute to the development of the main narrative. She noticed the author/illustrator’s name “Colin Thompson” on the front cover, and the copyright year “1995” on the first spread from the very start of her first encounter with the text. Paying close attention to these paratextual features enabled her to infer that the pictorial detail of “1994” was the author/illustrator’s “signature”: “I’m curious why he put 1994, specifically that year. And I saw here [pointing at spread 1] his copyright is 1995. So this is maybe his signature of when this was written” (my emphasis). She noticed the reappearance of the number “1994” on the second spread (“ah ~ the author is putting up 1994 again”), and predicted whether the popping up of “1994” would be a trend throughout. Her prediction was later confirmed. She then conjectured at the author/illustrator’s intention of inserting his “signature” into the text: “Oh, lots of play … how funny that he carries that through! I wonder if it’s more for his own satisfaction … maybe it doesn’t have anything to do with the reader.” Rihanna’s attempt to trace and account for the appearances of “1994”, “1995”, and “CT” reflected her intention to sort out consistency in the fictional world crowded with multilayered visual details.

What also stood out in Rihanna’s reading was that she treated some pictorial details as temporal markers, for instance, “the sunglasses that look like they can be from the sixties”, “a modern day pencil”, and the “floppy disk” that was popular more than ten years ago. Drawing on the paratextual knowledge of the text being produced in 1995, she placed the detail “record card” within the context: “So this was written in the nineties when that transition [from the use of record cards to that of computer catalogues in libraries] was happening. So there were still record cards. But computers were becoming a thing.” Therefore, Rihanna’s reading showed three salient features: first, proceeding from the notion of books as a physical space to that of books as an abstract carrier of life stories; second, striving to sort out consistency in the multilayered visual details, especially paying attention to the paratext; third, seeking temporal markers, and situating the picturebook in its context of production. Rihanna’s emphasis on the paratextual features revealed her awareness of fiction as a deliberate construction. The acquisition of the awareness that fiction is a constructed set of settings, events and characters has to do with the skill of abstract thinking (Nikolajeva, 2014, pp. 22-27).

4.4 Sophie

The visual image of two sloping books that form a tent on the title page caught Sophie’s attention from the beginning of her first encounter with the text. She associated the two sloping books with a “tent” and a “shelter”. Both “tent” and “shelter” denote space: the former is a concrete physical space, while the latter can be any refuge in a more abstract sense. The first impression of the book as a space was interweaved into her following reading. This echoes Ryan’s finding that when readers construct narrative space, the first impression is the strongest and not easily remedied, even if it is wrong (2003, pp. 214-242).

Fascinated with the visual representation of space and time in Forever, Sophie invented a new story based on the fictional world in the second reading. She inferred about the temporal dimension from pictorial details, and integrated the spatial construction with the sense of temporality:they [the person in a red top and the four old men on spread 9] might not be from the same time ‘cause they’re [pointing at the old men] dressed like in ancient costume, clothes. But then he’s [the person in a red top] obviously from the modern time. So it’s a journey into, like, beyond time. Time travel? Probably, or maybe there’s no sense of time within the bookshelf. ‘Cause maybe the past and the present are confused, mixed into that space. And how different spaces lay out, maybe space can represent time itself.

Sophie used the clothes as a temporal marker to infer that the five characters came from different times. She combined a mixture of time dimensions with a series of different spaces, and reached the conclusion that “space can represent time itself”. Her interpretation touched on the fundamental parameters of the fictional world.

To include the character of the ancient child in her story, Sophie suspended her knowledge of the original story conveyed in the verbal, and followed her train of thought:

I remember this is the ancient child, but then if we forget about that story, he [the character in the red top] came out of this wonderful space [the Chinese garden on spread 12], and then met this guy, who’s in charge of the whole city [laughing].

Early in her first reading, Sophie associated books as an actual living space with books as a carrier of abstract knowledge—“I wonder if those people live inside these books, do they read the books themselves? Or do they just automatically absorb all the information into their heads?” This interpretation fed into her understanding of the image of the ancient child. She associated the spookiness and gloominess of the image with the nature of knowledge:

And the person [the ancient child] who’s in charge of all the books is such a weird person. He’s both young and old because all the knowledge is old. But he’s young because all the knowledge apparently is trying to produce something new, and then make changes to the future … So it’s such a contradictory world.

She moreover incorporated into her story the visual detail of the yellow light that caught her attention from early on—the yellow light suggested a world of hope beyond.

Assembling the interconnectedness of space and time, books as a carrier of knowledge, and the yellow light, Sophie came up with a story about the limitation of knowledge and the need to look beyond it:

So maybe, the reason why he [the character in the red top] came into this library is because he’s very interested in learning … So either it’s a dream, or it’s what happens to him because he has this wish to live among all those books. So he came into this place, and then had a real experience of what it would be like to live among all those books. But actually living among the books, it turned out to be not that enjoyable [laughing] … So he realises that eventually we have to live in reality… So the ultimate spiritual home for me, well, from the point of view of this person, is not within the bookshelves, but back in reality [pointing at the last page]. Yeah, … that’s the story I would make.

In the last session, Sophie, based on her story, drew a picture of one person emerging out of darkness to look into the sunny world outside. Sophie’s story revolved around the issues that had attracted her from the very beginning. Her response adds to Ryan’s finding: the first impression of the space represented in literature can be elaborated in more detail, especially when the literary work provides sufficient fabrics for readers to work with, allowing their imagination and creativity to unfold.

5. Discussion

In this empirical study, the adult readers showed the tendency to use some pictorial details as temporal markers of the fictional world, while the child readers did not seem to. The theory of brain laterality may provide an explanation for this difference. The sense of time passing is associated with sustained attention (McGilchrist, 2012, pp. 75-76), that is, the type of attention closely relating to a coherent perception of the world (pp. 38-39). Since the right hemisphere governs sustained attention, the sense of the temporal flow, especially time as “something lived through”, arises in the right hemisphere (p. 76; my emphasis). The left hemisphere tends to perceive time as “an infinite series of static moments” (p. 76). The left hemisphere thereby has a particular advantage where there is an emphasis on “a point in time” (p. 77). The pictorial details used as temporal markers correspond to various points in time. The right hemisphere, compared to the left hemisphere, matures earlier, and gets more involved in early childhood mental activities (p. 88; Crago, 2014, p. 12). Presumably, this suggests that children likely have a stronger sense of time as a flow, something to be “lived through”, while adults may tend to use a few static points as temporal markers. This is precisely the case with the four readers in my study.

The readers externalised the idea of books as a living space for miniature inhabitants in different ways. Lucy and Oliver acted the idea out, orchestrating verbal language, pointing, gesturing, body movement, and laughing. Lucy’s performance was especially sensuous and musical. Lucy’s and Oliver’s performance showed their different attitudes towards the idea of books as a living space: Lucy seemed to be fascinated with living in books, while Oliver performed how unpleasant and dangerous it could be. This difference may relate to the fact that Lucy was fond of reading while Oliver was not a big fan of reading, as they claimed in the first session on reading interests and habits. Both Lucy and Oliver tried out the perspective of those who live in books. The fictional world can provide a safe zone to engage with various new things one has not encountered or cannot possibly encounter in real life, which may be especially beneficial for child readers as their repertoire of experience is in the process of forming and restructuring.

Rihanna and Sophie, when externalising the idea of books as a physical space, did not seem to engage the body as actively and deeply as Lucy and Oliver did. The difference, again, may be explained in terms of brain laterality. While the right hemisphere sees the self as embodied and within the world, the left hemisphere sees the self as abstract and isolated (McGilchrist, 2012, pp. 46-51, pp. 54-56). Through a more intimate connection to the more ancient layers of the brain, the right hemisphere is more closely involved in emotional life. The left is more responsible for making sense of the world through dividing it into manageable bits and pieces (pp. 51-53, pp. 59-64; Crago, 2014, pp. 8-10). To restate: compared to the left hemisphere, the right hemisphere matures earlier. Lucy and Oliver may have moved forward from early childhood, but Rihanna and Sophie had ten to twenty more years of training in and practice of language, abstract and critical thinking. Moreover, given their educational backgrounds, the adult readers must have a more developed capacity for a lefthemisphere dominant way of attending to the world. Both Lucy and Sophie showed a strong story impulse that, according to Crago, arises from the right hemisphere because of its close connection to emotion and experience (2014, p. 13). Lucy’s way of bringing the story to life relied on entrainment of the body in emotional expression, typical of a right-hemisphere dominant way of experiencing the world. Sophie leaned towards the left hemisphere’s manner of culling details as she read along, organising and reorganising them, giving patterns to them, constantly modifying the patterns, and weaving the details into a coherent whole.

When a researcher uses Thompson’s picturebooks with readers, the tightly packed visual details may serve as “points of fascination”, which means the aspects of a text that have a particular potential for triggering readers’ imaginative responses (Baird et al., 2016, p. 12). All the readers actively engaged with various points of fascination. Rihanna and Sophie displayed an especially strong tendency to sort out consistency in the world of overwhelming details. They traced, connected, and attempted to explain the repeated appearances of some pictorial details. This is typical of a lefthemisphere dominant need for making sense and taking control of a seemingly chaotic world. Despite the four readers’ different ways of engaging with the fictional world, they all seemed to enjoy the multilayered visual details, as manifest in their laughing and exclamations. Lucy’s and Oliver’s relationships with the fictional world were embodied while Rihanna’s and Sophie’s were more abstract yet no less creative. This gives rise to the reflection: what matters is not only what aspects of the text the readers come to have a relationship with, but also, and more importantly, how the relationship is, and how they come to have that relationship. The reflection is of central importance to the discussion of crossover picturebooks, wherein the key issue involved is how a text can appeal to different audiences.

Definitions of crossover picturebooks often emphasise that a text addresses adult readers and child readers on different levels yet in equal terms. The multileveled nature of crossover picturebooks may correspond to the multileveled engagement that texts can elicit from readers. The multileveled engagement is to a great extent the outcome of cognitive-affective skills and mechanisms engaged differently across children and adults. Therefore, the term “multileveled” in Beckett’s definition of crossover picturebooks (2012, p. 16) may be interpreted as on multiple cognitiveaffective levels. The actual readers’ responses also reveal an unexpected aspect of Forever’s crossover potential. Through picturing the books that, in different layouts and positions, shelter the miniature inhabitants, the visual foregrounds the materiality of books as objects that can evoke a tactile and sensuous experience. Such an experience parallels the readers’ ongoing process of closing and opening the book, fingering and turning the pages, pointing and trailing, going back and forth, and playing it around. All the readers mentioned books as a physical space. The foregrounded materiality of books then opens up avenues for thinking about books as an abstract space that stores massive information, knowledge and life stories. The move from materiality to abstraction is inextricably bound up with the way the human mind works—the understanding of more abstract concepts is grounded in our embodied experience (Lakoff & Johnson, 1999). Scholars often associate the picturebook’s capacity for appealing to diverse audiences with dual narrative, that is, the combination of the visual narrative and the verbal narrative. For instance, Beckett argues that dual narrative gives rise to experimentation and innovation, which is at the heart of picturebooks’ crossover potential (2012, p. 2). Scott argues that the dual narrative of picturebooks affords a unique opportunity for “the collaborative relationship” between children and adults (1999, p. 101). This study shows another aspect of the crossover potential particular to the medium of picturebooks: picturebooks can use the visual to flesh out the embodied experience, which can springboard further thinking about more abstract and complicated notions. This mode of representation corresponds to the way the human mind works, thus engaging children and adults alike.

Acknowledgements

The writing up of this study is supported by the research project “Contemporary Western Picturebook Theory” (18WWC005) funded by Jiangsu Planning Office of Philosophy and Social Science and the project “Chinese Picturebooks and Their English Translations” (2017SJB1318) funded by Jiangsu Education Department.

Language and Semiotic Studies2020年4期

Language and Semiotic Studies2020年4期

- Language and Semiotic Studies的其它文章

- Investigating Disfluencies in E-C Sight Translation

- The Pragmatics of the Rhetorical Question in Selected (English) Qur’an Chapters

- Making Meaning through Prepositions: A Model for Teacher Trainees

- Rhetorical Questions in Wen Xin Diao Long: An Enthymematic Analysis

- #Take Responsibility: Non-Verbal Modes as Discursive Strategies in Managing Covid-19 Public Health Crisis

- Miao Folk Music and the Marginal Modernism of Shen Congwen