黑人歌剧:大都会历史性回归现场舞台,《骨子里的烈火》纽约首演

司马勤

乐评是什么?报道实时资讯与发表个人评论的混合体。无论是什么情况,首先要抓住创新点或特别处,然后再考虑到自己——也许包括其他人——对事情的看法。正如作曲家兼评论家维吉尔·汤姆森(Virgil Thomson)曾经说的:“评价只属华彩部分,而不是主题。”

因此,在谈论歌剧《骨子里的烈火》(Fire Shut Up in My Bones)时,我打从一开始就意识到这部新作品的新闻“含金量”已相当丰富。作曲家是特伦斯·布兰查德(Terence Blanchard),编剧是卡斯·莱蒙斯(Kasi Lemmons),《骨子里的烈火》是纽约大都会歌剧院有史以来首部出自黑人作曲家与黑人编剧的制作。正如不少乐评人(还有历史学家)指出的那样,尽管曾经有黑人创作歌剧的先例(也有其他族裔作曲家挑选黑人主题的歌剧),但除了无所不在的《波吉与贝丝》外,那些作品都没有机会走出美国规模较小的州立或城镇剧院的舞台。另一方面,《骨子里的烈火》被选中,特别是在经历超过18个月没有现场演出的黑暗后,为美国规模最大的歌剧院重启大门拉开帷幕,这宗新闻的确难得——从更宏观的角度来看,这也代表着纽约自新冠疫情爆发后,在大型场馆内再次搬演现场演出的重要时刻。可想而知,这个制作本身就足以登上头条。

好了,我们更要谈谈这部作品首演时星光熠熠的氛围。除了创作团队以外,全黑人演员阵容在大都会舞台上亮相(当然,《波吉与贝丝》例外)也轰动一时,更何况开幕夜的观众席中坐了那么多有色人种。顺便说一下:这一切都不是巧合。

一年多来,当新冠疫情令全球停滞,美国人也经常提及另一宗“疫情”——黑人乔治·弗洛伊德(George Floyd)死于明尼阿波利斯警察之手,导致整个社会都在应对种族之间的紧张关系。众多古典音乐机构也受到牵连,饱受“白人特权”及“制度上的种族歧视”的指责,而大都会歌剧院更是众矢之的。

我们大可以依据统计数据辩论一番。在过去几个演出季中,大都会歌剧院聘请黑人演员的数量显著上升。众所周知,全球歌剧界的演员竞争激烈,因此我很想知道,受聘的黑人歌手与整体受过歌剧训练的黑人歌手人数的真正比例。我不得不提醒你,大部分白人歌剧演员想登上大都会歌剧院的舞台,同样也只是梦想。

大家议论得面红耳赤,很难冷静下来作客观分析。“黑人维权运动”(Black Lives Matter)抗议集会此起彼伏之际,绝大部分美国艺术机构都积极主动地公开发表声明,表示拥护种族多样性。很多院团(包括旧金山歌剧院与多个美国交响乐团)增设新的行政岗位,取名“首席多样性执行官”(Chief Diversity Officer)。大都会歌剧院对此也贡献出自己的力量,在网上免费点播项目里刻意安排了历史资料库中全部突显黑人演员阵容、曾在广播(从前的电视或电影节目)中播放过或近年高清转播过的剧目。

从节目策划的角度来看,交响乐团与室内乐组合应对“种族多样性”比较容易。因为疫情,早已定好的演出季都被腰斩,取而代之的是包括黑人与其他有色人种作曲家创作的音乐(最初只有线上节目)。歌剧院在节目策划方面则比较复杂,它们操作起来更像笨重的大恐龙。密歇根歌剧院(Michigan Opera Theatre)——在歌剧界中绝对算不上是大型机构——选中比它更小的歌剧院已经首演过的作品,如格里莫格拉斯歌剧节(Glimmerglass Festival)上演的《蓝》(Blue)或挑选已解散的歌剧院曾委约的作品,如纽约市立歌剧院(New York City Opera)委约的《X:马尔科姆·埃克斯的人生和时代》(X: The Life and Times of Malcom X)。

这也是《骨子里的烈火》(圣路易斯歌剧院委约作品,2019年首演)被选为大都会歌剧院重启演出季剧目的原因(这个新制作也会移师至洛杉矶歌剧院与芝加哥抒情歌剧院)。然而,该剧目的成功与否,却是另一个话题。

***

《骨子里的烈火》的新闻“含金量”實在太高了,难怪很少有评论家直接谈及该作品在艺术上可取之处(当然,在疫情肆虐的这些日子里,留给乐评的版面越来越小)。考虑到这个时代政治背景与面对种族多样性的敏感度,很多人都不敢过度批评这个制作。这是一个举足轻重的文化里程碑,何必去泼冷水呢?

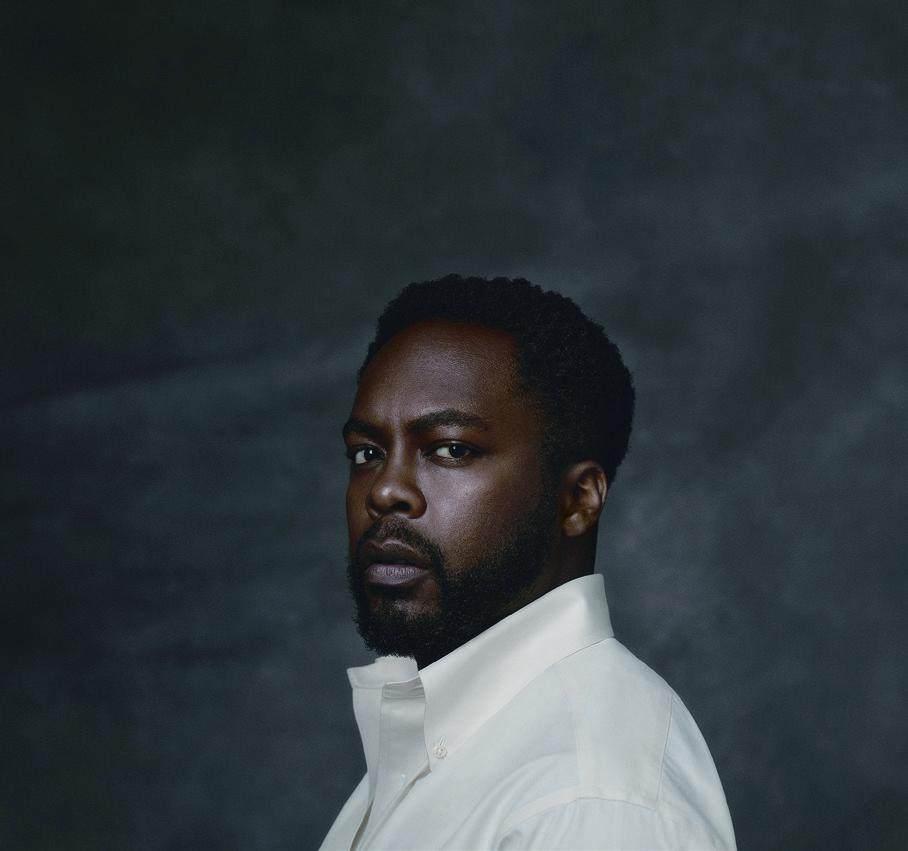

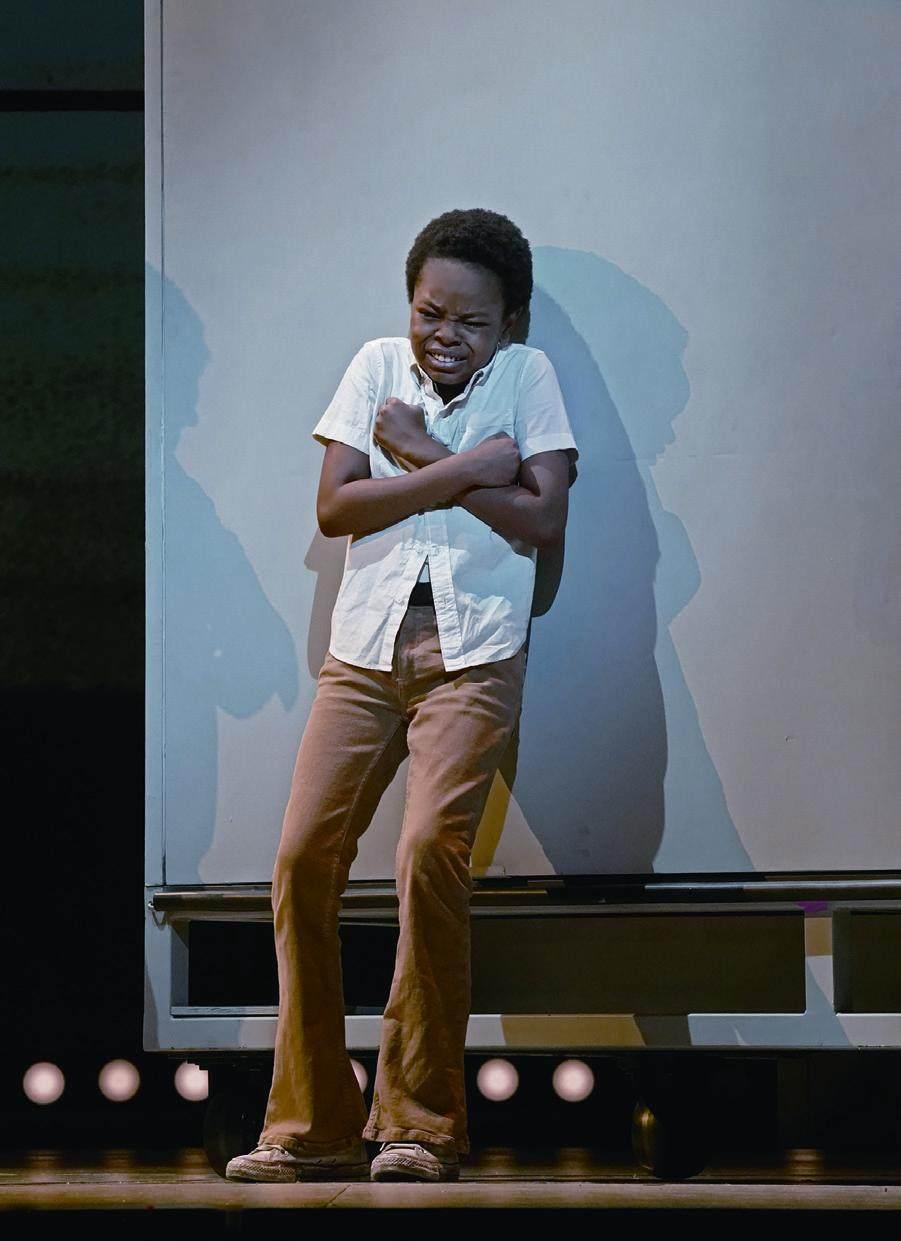

说实话,这部作品有不少值得钦佩的地方。布兰查德是一位杰出的爵士乐手,他的电影配乐也备受赞赏(最著名的是为斯派克·李的电影配乐),成就无可厚非,才华远超他身为黑人的种族标签。从剧本结构上,编剧莱蒙斯(她也是位电影导演)改写了《纽约时报》专栏作家查尔斯·布洛(Charles Blow)的同名回忆录,刻意增添了不少电影技法:在歌剧里,当成年的布洛回顾自己童年,舞台上也出现扮演年少布洛的演员。布兰查德在音乐处理方面也用上相仿的技法。歌剧中有一段二重唱,由成年布洛[男中音威尔·利弗曼(Will Liverman)]与童年的自己[可爱的童声男高音瓦尔特·罗素三世(Walter Russell III)]齐唱。

正如他的作品表显示的那样,布兰查德的风格覆盖面很广。诉说内心的唱段——成年布洛的沉思,或他对话“命运”与“孤独”[由女高音安吉尔·布鲁(Angel Blue)饰演,它们虽是抽象概念,却化为人物角色]——都抒情之至,引起超凡脱俗的遐想。故事中的各种合唱段落(都与戏剧情节有关)取材自福音音乐、蓝调布鲁斯音乐与具有黑人文化独特风味的乐派。可是,因为剧本本身建立于不平衡的结构上,这种二元性到了第二幕才完全展现出来。

我发现歌剧里一些不太合适的元素,但没有感到惊讶——从艺术上来说,似乎所有的叙事结构和音乐元素都被拉伸以填充更大的空间——后来知悉这些都是在该剧首演后,为了大都会的演出才添加的部分。舞台调动时不时会影响到叙事的畅顺性,尤其是布洛在大学参与兄弟会入会仪式那一段不但哗众取宠,更削弱了这部分场景应有的戏剧性。

一部本来属于描述亲密家庭的戏剧被扩大为一部大歌剧,可惜故事的情节与内容却无法符合大歌剧的要求。换句话说,像把一杯优质的香槟倒进空空如也的大酒钵。

***

我在看完《骨子里的烈火》离开大都会歌剧院之后,脑海里浮现了一个问题,一个平常看罢歌剧——甚至电影——都不该提出的疑问:这场演出删减了原著的哪些要素?从务实的层面来看,挑选布洛的回忆录作为歌剧主题很容易理解:把已经面世的畅销回忆录改编为歌剧当然是好事,尤其是对目标受众具有重要影响力的原著。我看罢演出却对歌剧版本缺乏热情,所以特意订购了原著,想要仔细研究一番。结果,我感到更加困惑:把这本回忆录改编为歌剧,是谁想出来的好主意?

我提出的疑问与原著的质量无关。这甚至是我近年来阅读过最震撼的回忆录。书中的叙事手法发自内心:我感觉到布洛年轻时所观察的事物的新鲜感和即时性,同时也接受成年的布洛的措词与角度。但在歌剧里面,那些重要的情节——孩提时代被性侵造成的内心创伤,长大后抓住宗教或兄弟会的机会寻觅出路(却都失败)——在布洛回忆录的字里行间既优雅又细腻;而在歌剧制作里,这些重要转折点却被沦为增添乐段的借口。

原著文本与歌剧制作的大反差让我想起几年前参加在马德里举行的世界歌剧论坛。其中一场讲座的主题关乎“多样性”。不同国家的代表对于“多样性”这个词语有不同的见解:经济多样性?文化多样性?但是,在美国人的心目中,“多样性”只有肤色的黑白之分。一位圣路易斯歌剧院董事局成员(一位美国黑人)占用了论坛差不多10分钟的时间。他痛斥那部深受欢迎的《波吉与贝丝》,并慨叹没有任何常规歌剧剧目能够“代表他的生活”。

我认为他没有抓住重点。我不确定,那些从高楼跳下自杀(《托斯卡》)、被满心嫉妒的士兵用刀捅死(《卡门》)或困在麻袋里继而被自己的父亲挥刀刺死(《弄臣》)——我只提出全球十部最有名的常规歌剧剧目中的三部——确实能反映现实生活吗?(尽管直至几年前,很少人会担心自己感染呼吸系统的病毒而致命。)

这位董事局成员好像搞不清生活与艺术的定义。数百年来,哲学家一直在争论这两者的相对优点,还有彼此间的相互影响。可是,哲学家通常不会把两者混淆。生活既漫长又凌乱;正如约翰·列侬(John Lennon)曾写道,生活正是“你在草拟其他计划时,围绕你发生的一切事情”。相对来说,艺术就是计划,它提供我们一些框架,把那些生活中的“上好部分”浓缩成可消化的120分钟(如果你是瓦格纳,那么就算成5个小时)。重点是:艺术超越于生活,提醒着我们悲伤或喜乐两大极端的可能性。

相比生活,艺术更容易被判断。艺术有它的常规:你可以务实处理,也可把热度调高至爆发点。如果你忽略它,你就会陷入危机。让我们重新审视《蓝》这个个案——移植到底特律演出后,作品的效果显得逊色——黑人警察的儿子被白人警察所杀的故事所引起的共鸣,连白人观众都会明白家中父子代沟的问题与街头发生的种族与社会冲突。这些都是编剧泰泽维尔·汤姆森(Tazewell Thompson)自身经历过或亲眼看到的现实。《蓝》的制作手法非常艺术化,套用了古代希腊悲剧方式。剧中几位女演员一开始就担心黑人小男孩未来的一生。她们就是希腊戏剧中的命运女神,只不过换上了现代戏服。

让我们回到《骨子里的烈火》:故事拥有电影的架构,可惜沒有找来称职的剪辑师。我感觉不到一场接一场的动力,场景间彼此没有关联或回应。很多场景在偌大的舞台上感到不太舒适——我肯定,在圣路易斯的舞台上以及那里的观众更适合这部家庭戏剧。

如果我更轻率的话,我会指出《骨子里的烈火》的问题在于没有人在剧中死掉:从历史角度来看,那是艺术与娱乐最显著的区别(百老汇的《西区故事》与歌剧界的《费加罗》算是个例外)。真正的问题所在,是创作者不懂歌剧的创作规律。

如果我要发传票的话,我会惩罚《骨子里的烈火》创作者违反了契诃夫法则(Chekhov’s Law),即假如手枪在第一幕出现,到了第三幕就必须要用得上这个道具。《骨子里的烈火》(歌剧与原著)一开始描述主人公拿着手枪开着快车飞奔回家,誓要找上当年侵犯他的表哥算账。后来(回忆录书中记载得更早),布洛的母亲[女高音拉托尼亚·摩尔(Latonia Moore)将该角色演绎得淋漓尽致]拿着同一把手枪指向不忠的丈夫与他的情妇。但她也没有扣动扳机。

无疑,故事中令人伤痛的情节让我们深信,《骨子里的烈火》的确是在描述生活。但这是艺术吗?传票已发出,法官已开审,但陪审团正在热议中仍未出庭。

All music criticism is a mixture of factual reporting and personal evaluation. No matter the occasion, you first need to find whatever is new or special, and only then do you get around to what you—and sometimes other people—thought of it. As the composer and critic Virgil Thomson once put it, opinion should be the cadenza, not the theme.

So when it comes to an event like Fire Shut Up in My Bones, there was already plenty of news to start with. Composed by Terence Blanchard with a text by Kasi Lemmons, Fire was the first opera by a Black composer and librettist ever to appear at the Metropolitan Opera. As some critics (and many historians) have pointed out, other Black composers have written operas (just as several non-Black composers have written on Black subjects), but rarely have any of them—other than the ubiquitous Porgy and Bess—made it beyond the regional stage.Fire, on the other hand, was chosen to reopen America’s largest opera house—and for all intents and purposes brought back live, large-scale indoor performances to New York—after more than 18 months of darkness. As such, the event itself was practically front-page news.

Then there was the evening’s general complexion. In addition to the creative team, rarely (except, of course, for Porgy) has an all-Black cast graced the stage of the Met, and never has a Met opening night had so many people of color in attendance. None of this, by the way, was a coincidence.

For more than a year, while Covid ran rampant throughout the world, people in America were also referring regularly to “the other pandemic.”Spurred by the death of George Floyd at the hands of the Minneapolis police, the entire country was reckoning with racial tensions throughout society. Among classical music institutions saddled with accusations of “white privilege” and “institutional racism,” the Met found itself particularly vulnerable.

One could surely debate the statistics. The number of Black singers appearing at the Met has noticeably appreciated in the past few years, and given the high level of competition in the field I would love to see the ratio of Black singers hired there versus the number of trained Black singers in the overall talent pool. Most White opera singers never make it to the Met either.

But you can’t expect objective analysis in such a heated debate. During the Black Lives Matter protests, nearly all American arts organizations made unsolicited statements stating their support of racial diversity. Many (including San Francisco Opera and several orchestras around the country) created new administrative positions with the title of Chief Diversity Officer. The Met, for its part, filled its nightly HD streams with every production featuring Black singers in its televised history.

In terms of programming, orchestras and chamber music societies had it relatively easy. Entire season schedules, many designed years in advance, were thrown out the window, replaced (initially on line) with much music by Black and other composers of color. Opera companies, by comparison, were the lumbering dinosaurs. Rather than creating anything new, even Michigan Opera Theatre—by no means a giant in the field—had to turn to pre-existing works and productions, usually done by organizations even smaller (Glimmerglass Opera, in the case of Blue) or now defunct (New York City Opera, in the case of X: The Life and Times of Malcom X).

Which is how Fire Shut Up in My Bones, originally commissioned by the Opera Theatre of St. Louis and premiered there in 2019, wound up reopening the Met (in a new production later traveling to Los Angeles Opera and the Lyric Opera of Chicago). Whether it actually succeeded, however, is another question entirely.

***

So much news value was wrapped up in Fire that it’s little wonder that so few critics (all of whom seem to have less space these days) got around to discussing the artistic merits of the piece. Nor, given the political times and cultural sensitivities, would many of them dare to. Why wreck a culturally significant moment with bad news?

The truth was, yes, there was much to admire.Blanchard, being a prominent jazz musician and an accomplished film composer (most notably in scores for Spike Lee), has much more to play than just the race card. Structurally, Lemmons (herself a filmmaker) reworked New York Times columnist Charles Blow’s eponymous memoir with a duly cinematic touch, with the mature Blow looking at the young Blow as an entirely different entity onstage. Blanchard follows suit, and even has the older Blow (played by baritone Will Liverman) singing a duet with his younger incarnation (the charming treble Walter Russell III).

As his résumé would suggest, Blanchard employs a huge stylistic range. Interior singing—as in the mature Blow’s reflective moments, or his interior dialogues with Destiny and Loneliness (both sung by soprano Angel Blue)—tended toward an otherworldly lyrism. Public singing, in those scenes portraying the past in real time, drew on gospel, blues and other vernacular styles. But given the structural imbalance in the libretto, this duality didn’t become fully apparent till after intermission.

I was not entirely surprised to find that everything that felt wrong at the Met—all the narrative and musical material that seemed like fabric stretched to fill a bigger space—was added since the original production. Much of the choreography simply got in the way of the story without adding to it, but one extended set piece relating Charles’s college fraternity hazing actually managed not just to pander to the crowd but actually trivialize the dramatic meaning of the scene.

What was basically an intimate domestic drama was puffed up into grand opera without the content to support it. It was like pouring a glass of nice champagne into an empty punch bowl.

***

I left the Met after Fire asking the one thing you should never need to ask after an opera—or even a film: What was lost from the original source? On a pragmatic level the choice of Blow’s book was obvious: it never hurts to adapt an existing bestseller, particularly one that carries significant weight with your target audience. My lack of enthusiasm actually sent me in search of the book, which only intensified my confusion: How could anyone have thought that it would make a good opera?

In no way does this question the quality of the book, which was in fact the most powerful memoir I’ve read in some time, with an interior narration that maintains the freshness and immediacy of Blow’s younger observations while the mature writer provides the vocabulary and perspective. But in the opera, none of the key developments—the personal trauma of childhood sexual abuse, or failed detours into religion and fraternity life to find direction—unfold with the grace and subtlety of Blow’s prose. At best, they become excuses for a new musical number.

The stark contrast between book and opera brought back an exchange I witnessed a few years ago at the World Opera Forum in Madrid, where one of the discussions focused on diversity. Depending on the nationality of the delegates, diversity was often defined as economic or cultural, but for Americans it was literally a matter of Black and White. One Black board member from the Opera Theatre of St Louis hijacked the discussion for nearly 10 minutes lambasting the popularity of Porgy and Bess and lamenting the lack of anything in the opera repertory that “represented his life.”

I think he rather missed the point. I’m not sure how much jumping to your death from a parapet (Tosca), getting stabbed by a jealous soldier (Carmen) or getting pummeled to death in a bag by your father(Rigoletto)—to cite but three of the top 10 operas in the repertory—represents anyone’s life today.(Though until just a couple of years ago, a fatal respiratory ailment didn’t seem very common either.)

The problem our board member seemed to be having was a general misperception of life and art. Philosophers for centuries have debated the relative merits of the two, as well as their mutual influences on each other. But rarely have they confused them. Life is sprawling and messy; as John Lennon once wrote, it’s “what happens when you’re making other plans.” Art, on the other hand, is the plan, the structure of how to condense the “good parts”into a digestible 120 minutes (or if you’re Wagner, five hours). The very point that art transcends life reminds us of extreme possibilities on both ends of the ecstatic-tragic spectrum.

And compared to life, art is much more open to judgment. Art has conventions, which you can treat faithfully or tweak to the breaking point. But you ignore them at your own peril. Looking at Blue—which in Detroit suffered even more in its transfer of venue—the story of a Black policeman’s son being killed by a White policeman resonated with youth-parental tensions at home and racialsocietal conflict on the streets. It rang true even for White audiences, mostly because librettist Tazewell Thompson had seen and lived much of it himself. The presentation, however, was supremely artful and thoroughly realized through the conventions of ancient Greek tragedy. The women initially expressing concern about the future of Black boy baby were nothing but the Fates in modern dress.

But turning to Fire, the story unfolded with all the structural points of film without a suitable editor. Scenes didn’t push from one to the next as much as just end and start anew. Nor did much of the story seem comfortable on stage—though I’m sure the scale in St. Louis was more hospitable to domestic drama.

If I were more flippant, I’d say the problem in Fire is that nobody dies, which has long been a shorthand determination between art and entertainment (though it doesn’t quite account for West Side Story on Broadway or Figaro on the opera stage). The real problem, though, was its ignorance of conventions.

Handing out citations, I would fine the creators of Fire Shut up in My Bones for a clear violation of Chekhov’s Law, the principle that if you show the gun in Act I someone has to use it by Act III. Fire (both the opera and the book) opens with the protagonist racing in a car with a loaded weapon to confront the cousin who abused him. Later in the telling (though earlier in the story), the protagonist’s mother(brilliantly played by soprano Latonia Moore) chases after her unfaithful husband and his mistress with the same gun. But she doesn’t shoot anyone either.

So in its sometimes painful accounts, Fire Shut Up in My Bones is undeniably life. But is it art? The citations have been issued and the judge has presided, but the jury is still out.

——献给邱少云