COVID-19 in a liver transplant recipient: Could iatrogenic immunosuppression have prevented severe pneumonia? A case report

Anna Sessa, Alessandra Mazzola, Chetana Lim, Mohammed Atif, Juliana Pappatella, Valerie Pourcher, Olivier Scatton, Filomena Conti

Abstract

Key Words: Liver transplantation; COVID-19; Immunosuppression; Gastrointestinal symptom; Infection; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a highly infectious viral disease with over 3 million confirmed cases globally and over 200000 deaths. On the 30thof January 2020, the World Health Organization declared the Chinese outbreak of COVID-19 as a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern”. To contain COVID-19, their Emergency Committee recommended the need for early detection, isolation, contact tracing as well as prompt treatment. However, despite rigorous efforts by governments globally to contain this virus, its incidence continues to rise[1].

Solid organ transplant (SOT) recipients are under chronic immunosuppression and thus, at an increased risk of developing opportunistic infectious diseases. Amongst SOT patients, the early clinical reports of COVID-19 have been limited to heart and kidney transplant recipients only. In this report, we describe the management of COVID-19 infection in a liver transplantation (LT) recipient[2].

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 58-year old black male who was 18 mo’ post LT presented to our Emergency Department with abdominal pain.

History of present illness

On the 9thof March, he developed epigastric pain radiating to the right hypochondrium as well as nausea and vomiting. He had no fevers, cough, shortness of breath, anosmia or dysgeusia.

History of past illness

The liver transplant had been performed in July 2018 for hepatocellular carcinoma and end-stage liver disease secondary to hepatitis B (HBV). He was on tacrolimus-based immunosuppression in mono-therapy since July 2019 and took a nucleoside analogue for HBV graft reinfection prophylaxis. He had stopped mycophenolate mofetil because of repetitive urinary infections.

Unfortunately, this gentleman’s early and late post-transplant course was complicated by the need for further surgical and endoscopic interventions. In November 2018, he underwent emergency laparotomy for adhesional bowel obstruction during which a colostomy was formed. In January 2019, he presented with repetitive cholangitis and iatrogenic acute pancreatitis. This was related to issues with biliary drainage and thus, was resolved after undergoing an endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography.

In terms of other relevant medical history, he took aspirin as thromboprophylaxis for prevention of hepatic artery thrombosis and was on amlodipine for arterial hypertension. He denied any history of recent foreign travel or exposure to others infected/suspected of COVID-19.

Personal and family history

The patient did not smoke or consume alcohol. There was no noteworthy family medical history.

Physical examination

His physical examination was unremarkable.

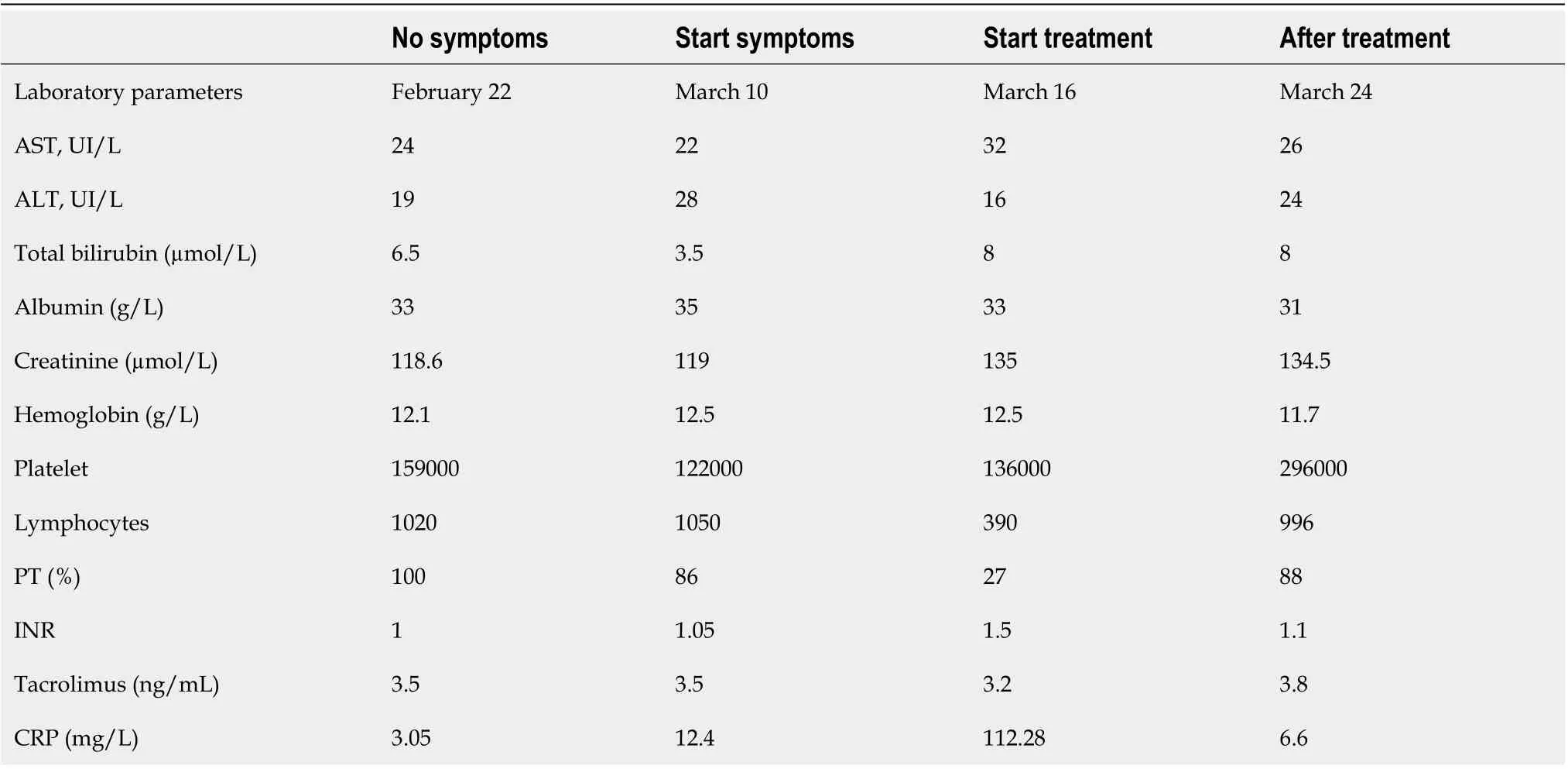

Laboratory examinations

On the 10thof March, his laboratory results revealed; low lymphocyte count, percentage of lymphocytes and a slightly increased C-reactive protein (CRP) at (12.4 mg/L). There were no other abnormalities identified (Table 1).

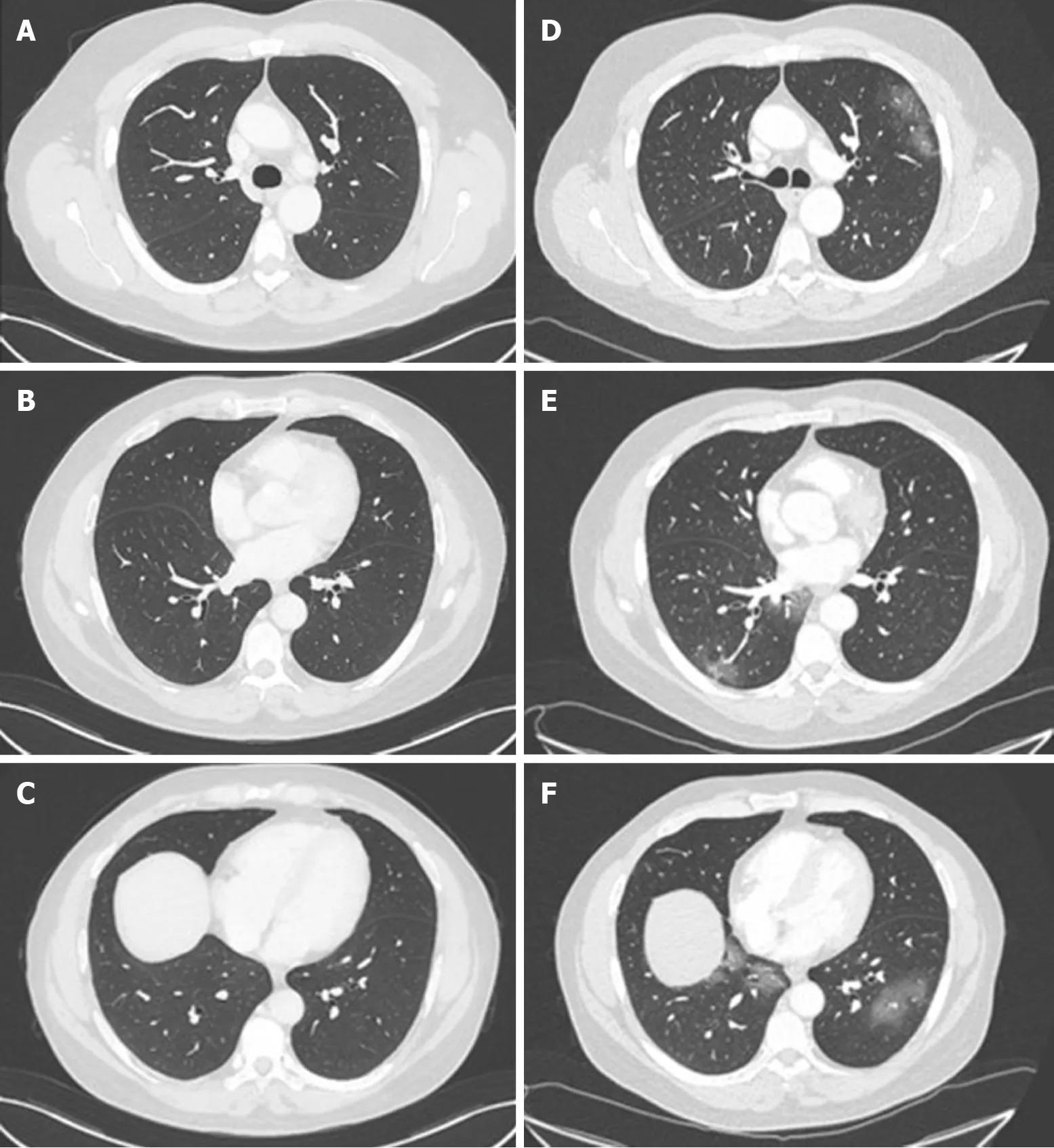

Imaging examinations

His abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast was unremarkable from the abdominal perspective however, the lower chest slices identified multiple bilateral patchy ground-glass density shadows. For this reason, the 12thof March, he underwent a formal chest CT scan, which revealed an extension of the multiple patchy groundglass density shadows to the upper lobe of the left lung too (Figure 1). All of this was suggestive of COVID-19 pneumonia and the patient was hospitalised in infectious disease department of our hospital the same day.

Further diagnosis work-up

At admission, he remained afebrile and his clinical observations such as blood pressure, pulse, blood oxygen saturation (98%) were all within normal ranges. The body mass index was 22 kg/m2. He thus did not require intensive support neither oxygen therapy. On examination of his chest, there were no positive cardiac- or pulmonary-related findings. However, upon abdominal examination, he continued to have epigastric pain radiating to the right hypochondrium.

His laboratory results revealed an exacerbation of the lymphocyte counts and percentages as well as an increase in his CRP (112.28 mg/L) (Table 1). There were no abnormalities in his liver and kidney biochemical markers. In terms of confirming COVID-19, his nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swab specimens came back as positive using the real-time polymerase chain reaction.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The radiological and virological characteristics were strongly suggestive for COVID-19 pneumonia with gastrointestinal involvement in a LT patient.

Table 1 Laboratory tests of patients

TREATMENT

On the 16thMarch, he received a course of oral chloroquine (200 mg × 3 per day) for a period of 10 d. No antibiotic treatment was administered. We made no modifications to his tacrolimus dosing (serum level was 3.8 ng/mL).

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

He was successfully discharged to advice to finish his course of chloroquine at home and self-isolate. We performed subsequent follow-upviatelemedicine. At the end of his treatment, his abdominal pain had resolved and his laboratory results were normal too (Table 1). After two months of COVID infection, no clinical and biological abnormalities have been found during our medical consultation.

DISCUSSION

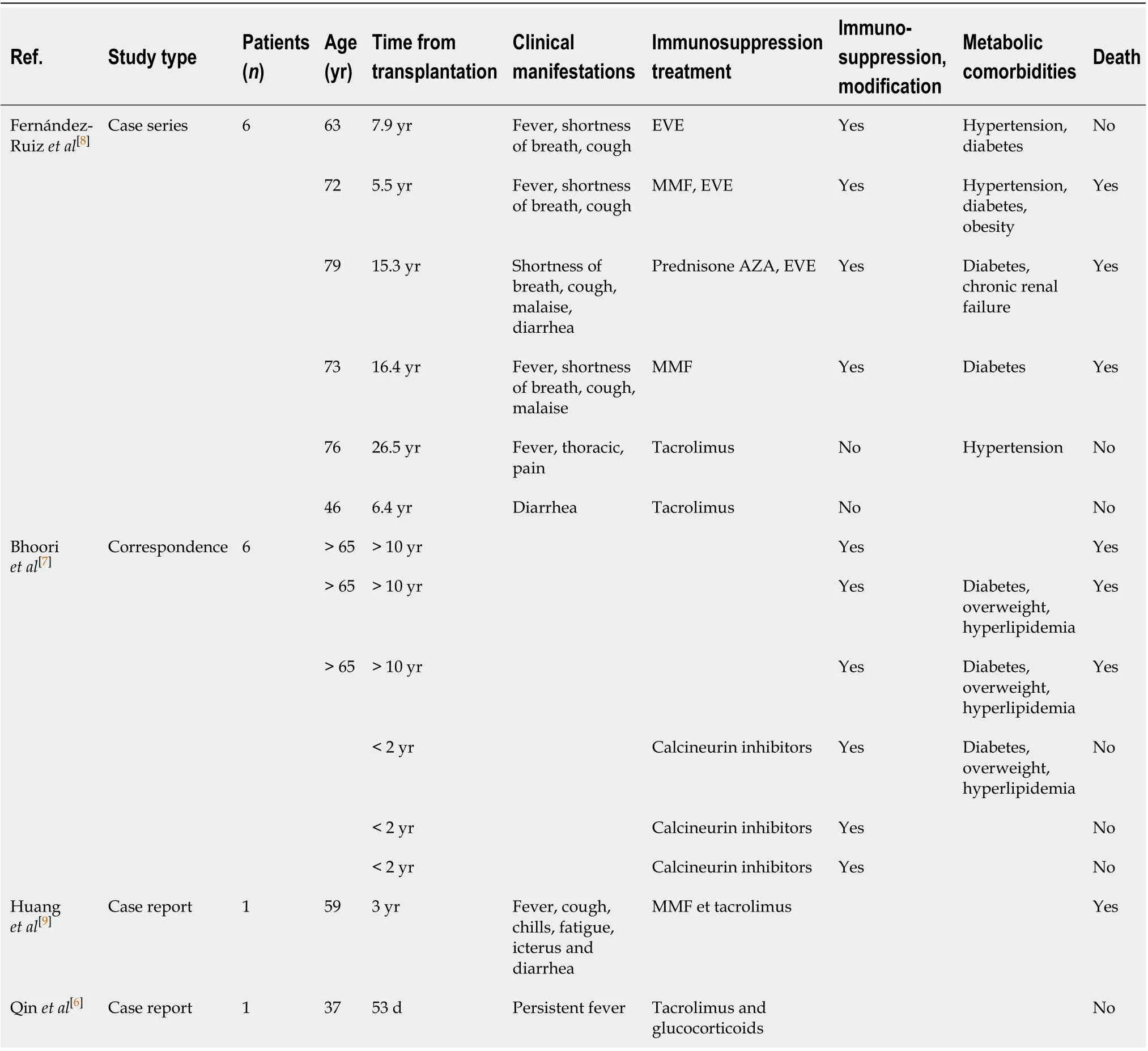

There remains limited knowledge of the impact of COVID-19 in SOT patients. It is all the more challenging for LT as recent case reports have been limited to kidney and heart recipients only[3-5]. In a previous manuscript, Qinet al[6]described the diagnose of COVID-19 in a LT-recipient during the peri-operative period. This was put down to an unrecognized infection caught pre-transplantation. Also, few cases are recently reported in Lombardia transplant centre, in a Spanish series of SOT and in a Chinese report for a total number of 7 patients[7-9]. The clinical characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19 LT patients are summarized in Table 2. To our knowledge, our report is another case of COVID-19 infection in a patient after 2 years of LT.

Symptoms

Infections might be considered in the differential diagnosis in the case of changes in clinical status of SOT even in the absence of common signs or symptoms of infection. Data showed that, fever and physical signs of all types of infection in SOT patients, especially pulmonary and gastrointestinal infections, are diminished with subtle laboratory or radiological signs[10].

For symptoms of COVID-19 infection, it seems that SOT patients consistently have atypical presentations.

Our patient had epigastric pain, nausea and vomiting without any symptomsclassically associated with COVID-19. A recent manuscript regarding COVID-19 infection in a heart transplant recipient reported that their patient presented with fever, diarrhoea, fatigue but no respiratory symptoms[3]. Also, in the Spanish case series, the authors reported 6 cases in liver transplant recipients: Five of them presented with respiratory symptoms, one presented with only diarrhoea[8].

Table 2 Clinical and biological characteristics of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia after liver transplanta

Interestingly, a different report in a patient post-kidney transplantation described that their patient presented with conjunctivitis. Although this could be because the virus is present in conjunctival secretions, < 1% of other COVID-19 patients present in this manner[5].

In terms of explaining the modality of our patients’ gastrointestinal symptoms, these could be due to the presence of the angiotensin-converting enzyme II (ACE2) receptors in the upper oesophagus (stratified squamous epithelium) and intestinal enterocytes. The ACE2 receptor is the entry mechanism for the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) virus into human cells. This receptor is also highly expressed in alveolar type II pneumocytes, which may the development of respiratory symptoms classically associated with COVID-19 infection. Upon intracellular entry, the host transmembrane serine protease enzyme (TMPRSS) helps to release the viral proteins into the cell. It is plausible that the presence of the ACE2 receptors on the gastrointestinal cells may explain the occurrence of abdominal pain and diarrhoea[11]. The SARS-CoV-2 virus has been found in faeces and stool samples even when it is no longer detectable in the respiratory tract. This suggests the possibility of a faecal–oral route of viral transmission[12].

Figure 1 Chest computed tomography of a 58-year-old man who underwent liver transplantation in 2018. A-C: Normal chest computed tomography (CT) of the patient in November 2019; D and E: Chest CT on admission in March 2020 showing ground-glass opacities with a peripheral distribution.

Immunosuppression management

The risk of serious infections in SOT is determined by interactions between the patient’s epidemiological exposures and the state of immune suppression. In case of infection, the reduction in immunosuppression may be a useful component of antimicrobial therapy but with an increased risk of graft rejection or immune reconstitution syndromes. Reduction in specific immunosuppressive regimen should be roughly linked to the host responses desired for the pathogens encountered (e.g., steroids for bacteria and fungi, calcineurin inhibitors for viruses, cell cycle agents in neutropenia) recognizing that each agent has multiple effects on the immune system[10].

In our case, instead, our decision to continue tacrolimus at the same dose was based upon recommendations from The French Society of Transplantation as well as the recent joint position paper by The European Society for Study of Liver (EASL) and European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID)[13,14]. The French guidelines recommended that LT recipients who were more than a year posttransplant to make the following modifications to their immunosuppression regimens[13]: (1) Patients on dual therapy of tacrolimus/mycophenolate plus mammalian transporter of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor: Maintain the tacrolimus/mycophenolate, however discontinue the mTOR inhibitor; and (2) Patients on monotherapy with mycophenolate acid or mTOR inhibitor: Maintain the same treatment at the same dose.

In parallel, the EASL-ESCMID recommendation was to only reduce immunosuppression dosage under special circumstances (e.g., drug-induced lymphopenia, or bacterial/fungal superinfection in the case of severe COVID-19)[14]. Furthermore, the safety of immunosuppression therapy was confirmed in a recent case series from Italy, in which immunosuppression seemed not to increased risk of severe pulmonary disease in children who had received liver transplants, compared with the general population[15]. In comparison with Lombardia experience, and in line with Spanish experience, no change in immunosuppression therapy was done[7,8]. Although our patient neither stopped nor reduced immunosuppression, they had a favourable outcome using an experimental treatment. In conclusion, it seems reasonable that all these decisions were to be made in close consultation with the patients’ local transplant hepatologist[14].

Overall, there is limited data regarding immunosuppression management in COVID-19-positive transplant patients. In these patients, it is critical to get the right balance between protecting the allograft as well as aiding the immune system in mounting an effective anti-COVID-19 response. Moreover, it is most concerning that a subgroup of non-transplant patients with severe COVID-19 have been shown to develop a cytokine storm-like syndrome involving haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and multi-organ failure[16]. The authors who identified this suggested that all patients with severe COVID-19 should be screened for hyperinflammation to identify the subgroup for whom immunosuppression could prevent mortality[16]. This is amongst one of the primary reasons for which clinical trials are underway to test a broad range of anti-inflammatory agents (e.g., steroids, intravenous immunoglobulins, anti-IL-1, anti-IL-6, and JAK inhibition)[17,18]. In the case of our patient, we would speculate that the continued use of tacrolimus in our patient could have in parallel, also protected against the cytokine storm syndrome.

设计意图: 运用动画把体液免疫和细胞免疫的过程形象生动地展示出来,引导学生通过动画获得感性认识,接着用概念图去呈现这两者的概念模型,对知识点达到更深层次的认识。体液免疫和细胞免疫作用独特,相互配合,共同发挥免疫效应,但是不是免疫系统的防卫功能越强大越好呢?免疫系统功能不足或缺陷以及免疫系统功能过于强大会引起什么疾病?通过提问引发学生思考,学生要正确认免疫系统的防卫功能,在遇到其他事情时,也要理性思考,要全面地考虑问题,让科学思维成为一种习惯。

Treatment of COVID-19 pneumonia and outcomes

When infections occur in SOT were associated with an increased risk of morbidity and mortality especially in the first three months after transplantation[10]. A rapid diagnosis and the beginning of a specific therapy consent an improvement in a clinical outcome.

Our patient received a 10-d course of chloroquine rapidly after diagnosis with no reported side effects. However, it is important to consider that there is currently no global consensus on the ideal treatment for COVID-19 infection in transplant and nontransplant patients. It is all the most challenging in transplantation as we generally have a lower threshold to treat other opportunistic infections.

An early clinical trial from China conducted in COVID-19-positive non-transplant patients demonstrated that chloroquine had a significant effect, both in terms of clinical outcome and viral clearance. Indeed, the Chinese guidance recommends the use of chloroquine as a treatment for COVID-19 pneumonia regardless of severity[19,20]. Furthermore, a recent French trial conducted reported the efficacy of hydroxychloroquine treatment in reduction and suppression of viral load for COVID-19 patients[21]. In our case, it is theoretically plausible that, although chloroquine could have reduced viral load, the concomitant tacrolimus inhibited the inflammatory cascade involved in the propagation of severe respiratory symptoms[22].

Moreover, few data are available regarding the outcomes on COVID-19 liver transplant patients. As reported in Table 2, three of among 111 patients liver transplant survivors (transplanted more than 10 years ago) died following severe COVID-19 disease[7], 3 patients died in a Spanish series and, a fatal case of COVID pneumonia after 3 years of LT in a 59 old man with probably overlap chronic rejection was reported by Huanget al[9]Although the favourable outcome of our patient find another explanation also in scarce presence of metabolic-related comorbidities (only arterial hypertension), normally increased with time since transplant[2,23], that might be associated with an increased risk of severe COVID-19 disease.

CONCLUSION

To our knowledge, this is one of few uneventful reports about COVID-19 infection in a patient post-LT. He had atypical symptoms which successfully resolved with chloroquine treatment and continued tacrolimus. We would recommend that screening for underlying COVID-19 infection be performed in all immunocompromised patients presenting with atypical symptoms. The recommendations from the national guidance should been modified with the evolution of our understanding of this disease and its treatment.

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年44期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年44期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Prognostic value of changes in serum carcinoembryonic antigen levels for preoperative chemoradiotherapy response in locally advanced rectal cancer

- Hepatocellular carcinoma with tumor thrombus in bile duct: A proposal of new classification according to resectability of primary lesion

- Fatty liver is an independent risk factor for gallbladder polyps

- Artificial intelligence based real-time microcirculation analysis system for laparoscopic colorectal surgery

- Emerging use of artificial intelligence in inflammatory bowel disease

- Endoscopic pancreaticobiliary drainage with overlength stents to prevent delayed perforation after endoscopic papillectomy: A pilot study