COVID-19-associated stroke risk: Could nutrition and dietary patterns have a contributing role?

Melika Hajimohammadebrahim-Ketabforoush,Mohammad Reza Shahmohammadi, Alireza Zali, Zahra Vahdat Shariatpanahi,

Melika Hajimohammadebrahim-Ketabforoush, Zahra Vahdat Shariatpanahi, Department of Clinical Nutrition and Dietetics, Faculty of Nutrition Sciences and Food Technology, National Nutrition and Food Technology Research Institute, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran 198161957, Iran

Mohammad Reza Shahmohammadi, Alireza Zali, Shohada Tajrish Comprehensive Neurosurgical Center of Excellence, Functional Neurosurgery Research Center, Shohada Tajrish Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran 193954741, Iran

Abstract The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 has created a life-threatening world pandemic. Unfortunately, this disease can be worse in older patients or individuals with comorbidities, having dangerous consequences, including stroke. COVID-19–associated stroke widely increases the risk of death from COVID-19. In addition to the personal hygiene protocols and preventive policies, it has been proven that immune-compromised, oxidative, and pro-coagulant conditions make a person more susceptible to severe COVID-19 complications, such as stroke; one of the most effective and modifiable risk factors are poor nutritional status. Previous literature has shown that healthy dietary patterns, such as the Mediterranean diet, some food groups, and specific micronutrients, reduce the risk of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. In this work, for the first time, we hypothesized that a healthy diet could also be a protective/preventive factor against COVID-19–associated stroke risk. In order to prove this hypothesis, it is required to study nutritional intake and dietary patterns in patients suffering from COVID-19–associated stroke. If this hypothesis is proven, the chronic supportive role of a healthy diet in critical situations will be highlighted once again.

Key Words: COVID-19; COVID-19–associated stroke; Nutrition; Dietary patterns; Food group; Inflammation

INTRODUCTION

Due to the significance of the current pandemic, many studies have paid attention to its consequent clinical outcomes. Clinical manifestations can astonishingly vary from asymptomatic to the most life-threatening conditions resulted from cytokine storm[1,2]. Currently, the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)–associated stroke is not common and, simultaneously, is one of the most deteriorate consequences of this infection, particularly in those with severe infection[3,4], which is responsible for the mortality of about 40% of affected patients if it occurs[5,6]. Stroke, in turn, is the second cause of death and the leading cause of disability[7]. Although it is not yet exactly clear COVID-19 to be a culprit in the co-occurrence of stroke in infected patients[8], studies have shown that the incidence of stroke in COVID-19 patients is about 0.9% to 2.7%[6,8]. COVID-19–associated stroke is often an acute ischemic stroke, while hemorrhagic stroke also is rarely reported, especially in elderly[5,9]. Although some studies have reported stroke in young COVID-19 patients[10], a systematic review and metasummary of the literature have shown a mean age of 63.4 ± 13.1 years and the simultaneous presence of cardiovascular comorbidities[6]. Hypertension, diabetes, and inappropriate cholesterol levels are the main comorbidities associated with the severity of COVID-19[11]. On the other hand, the available data, indeed, suggest that severe COVID-19 can lead to stroke[6,9]. Preventive strategies and available health-promoting protocols based on antiviral therapies, immune modulators, and anticoagulants to reduce the severity of this disease appear to be significant and interesting points to be studied[12]. However, lifestyle has always been the most modifiable factor influencing diseases, of which nutrition is a vital part[13-15]. The role of healthy nutrition in the prevention and treatment of hypertension, diabetes, high serum levels of cholesterol, all of which predispose a person to stroke, and most non-communicable diseases has also been proven[16-18]. Recently, researchers have discussed immune-modulatory properties and other various effects of healthy nutrition on COVID-19 and its complications[13-15,19-21], among which no attention has been paid to COVID-19–associated stroke.

HYPOTHESIS

A vast body of evidence-based data from the past to the present has shown that healthy eating can prevent hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke[22-24]. Protection against hyper-inflammatory and hypercoagulable states and a pleasant change in metabolites derived from intestinal microbiota leading to cardiovascular health are the mainstream mechanisms involved[25]. Although there is no study concerning nutrition in COVID-19–associated stroke yet, there are growing studies addressing the impact of healthy diets, certain food groups, and some specific nutrients on COVID-19[13-15,19-21]. In these studies, healthy nutrition and some nutrients or nutraceuticals are considered mitigators of the disease severity and cytokine storm. On the other hand, some data have shown stroke as the worst event following COVID-19, occurring under cytokine storm and hypercoagulable conditions[26]. Altogether, the above-mentioned evidence creates the speculation that people who adherence to a healthy diet and lifestyle may be less likely to have a stroke following COVID-19 affliction.

EVALUATION OF THE HYPOTHESIS

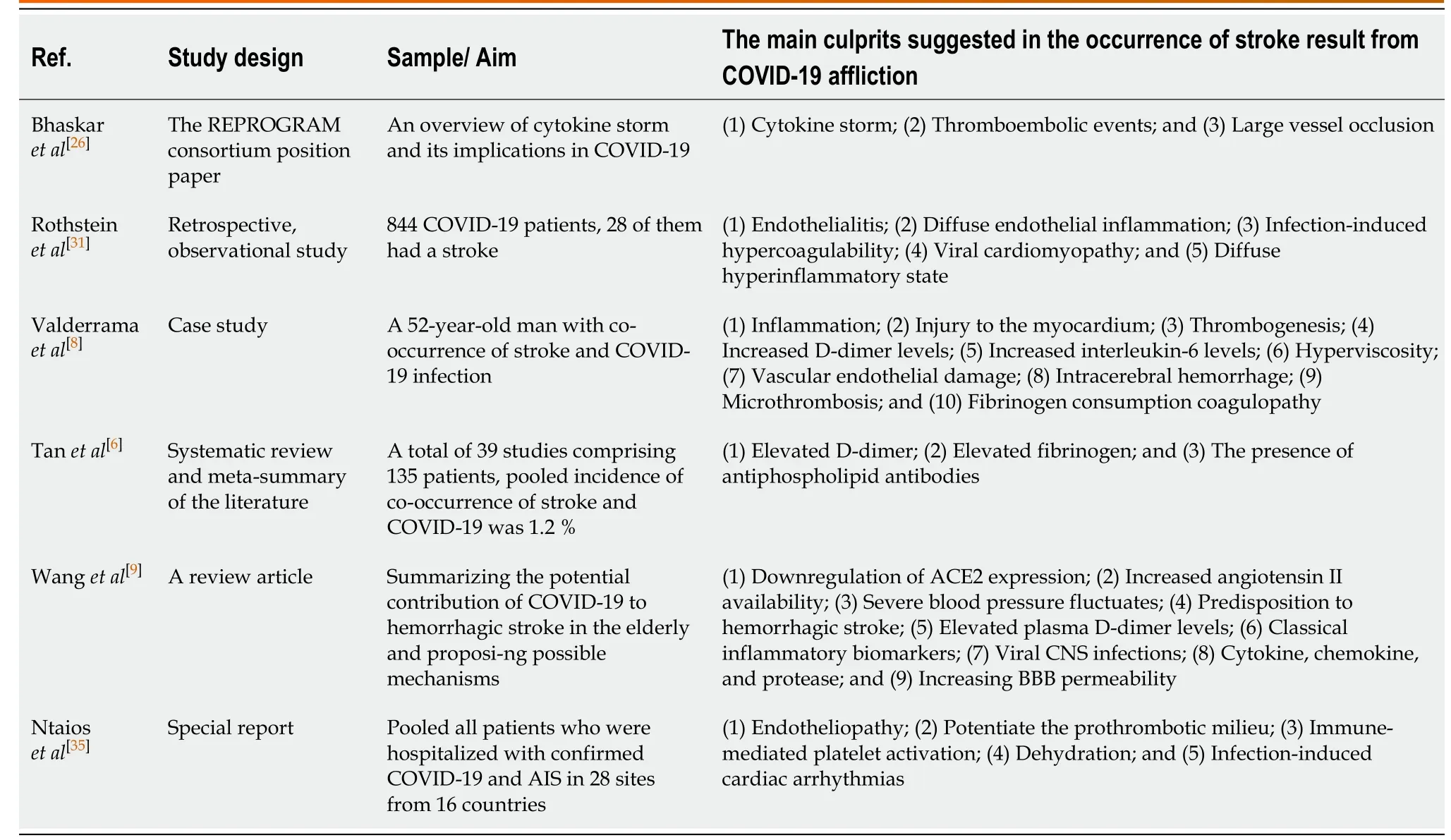

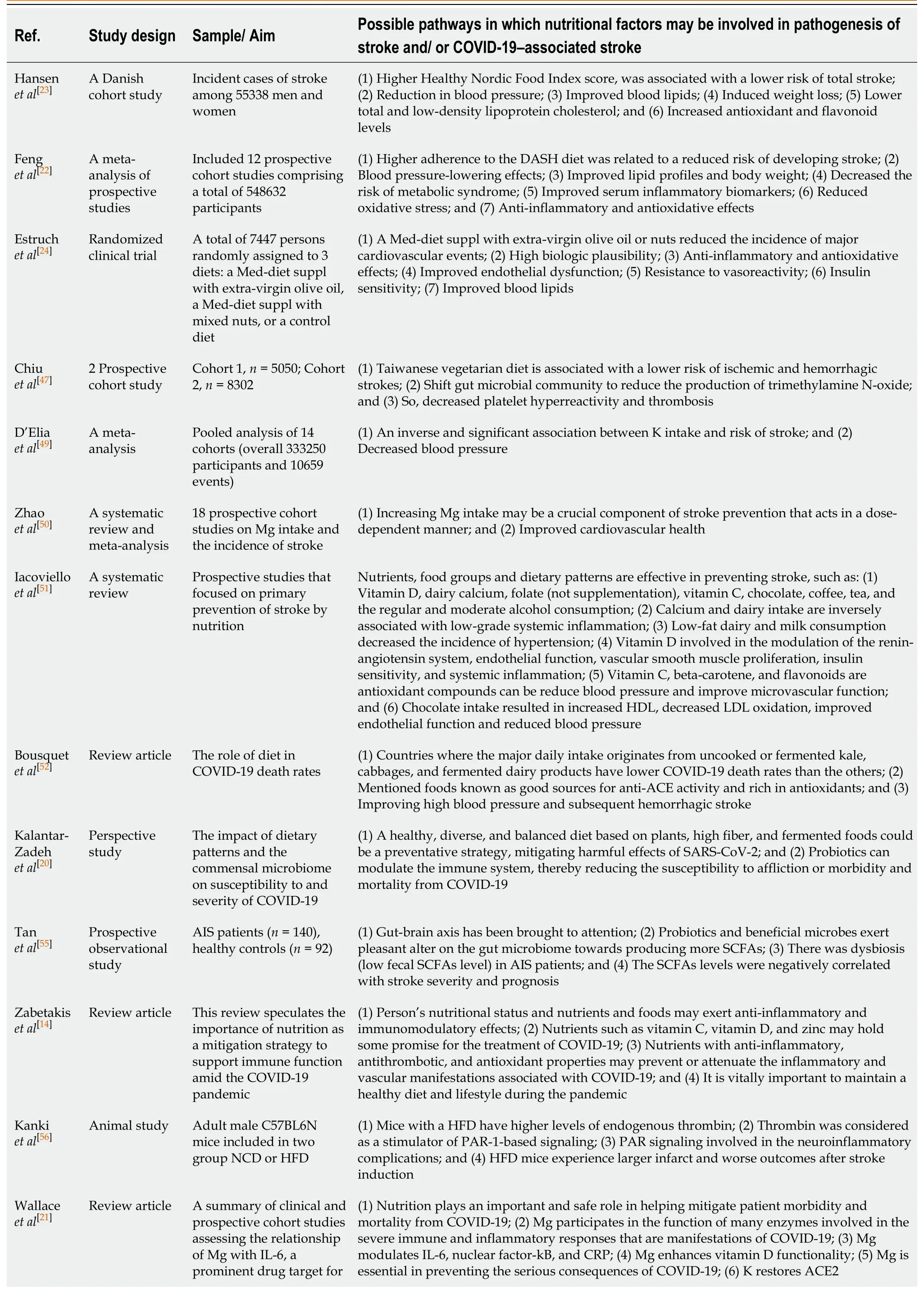

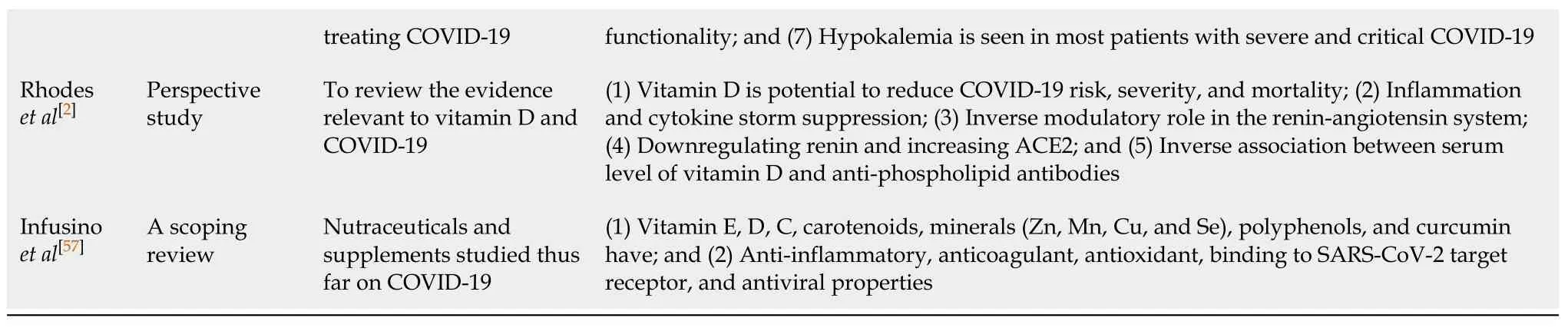

To evaluate our hypothesis, we conducted a comprehensive review by searching both pubmed.gov and scholar.google.com to first understand the association between stroke and COVID-19 and second review the studies in which nutrition has been linked to stroke and COVID-19. The former results are shown in Table 1, and the latter in Table 2. We also explain them in detail below.

COVID-19–ASSOCIATED STROKE RISK

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection enters the target cellviathe angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor[12]. In addition to the lung, this receptor is present in the endothelial cells, heart, kidney, and intestine[27]. This is an underlying cause of beyond respiratory manifestations of COVID-19. Once the virus infects the endothelial cells lining blood vessels beds, inflammatory cells and apoptotic bodies are accumulated; this results in vascular endothelial dysfunction, shifting vascular autoregulation to vasoconstriction, and organ ischemia, tissue edema, and pro-coagulant condition consequently[27,28]. On the other hand, immune-mediated recruitment of immune cells elevates the inflammatory responses and hyper-inflammatory states, leading to cytokine storm in severe cases. Cytokine storm plays a key role in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 manifestations, including acute ischemic stroke caused by hypercoagulable state[26]. Similar to other viral syndromes, SARS-CoV-2 is associated with an increased risk of stroke[29,30]. Elevated interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels following cytokine storm cause hyperviscosity[8]. Thus, besides the mechanisms, including infection-induced hypercoagulability, viral cardiomyopathy, and a diffuse hyperinflammatory state[27,28,31], proposed so far for the association between COVID-19 and acute ischemic stroke, a mechanical factor as dehydration can also increase stroke risk[8,32]. By comparing measured biomarkers in severe COVID-19 patients with moderate cases, a study has shown higher levels of alanine aminotransferase, lactate dehydrogenase, Creactive protein (CRP), ferritin, D-dimer, IL-2R, IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α in severely infected patients. Furthermore, the total number of T lymphocytes, CD4+T cells, and CD8+T cells significantly are lower in severe cases than those moderate. Therefore, they have concluded the cytokine storm to be related to disease severity[33]. A recently published systematic review further reveals the outstanding presence of raised Ddimer, fibrinogen, and anti-phospholipid antibodies in COVID-19 patients with coincide acute ischemic stroke[6]. Thus, the speculate on COVID-19–associated stroke is consistent with previous studies, which have well demonstrated that higher levels of D-dimer significantly associated with older age and pre-existing comorbidities are related to worse complications and death from COVID-19[9,34]. According to a report by Ntaioset al[35], COVID-19-associated ischemic stroke is more severe with poorer outcomes and higher mortality than ischemic strokes unrelated to COVID-19. Although most studies have discussed ischemic stroke, there is little data to suggest that SARS-CoV-2-induced diffuse endothelial inflammation also could be a mechanism resulting in hemorrhagic stroke[31]. On the other hand, as stated, the infection caused by SARS-CoV-2 is mediated by the host cells ACE2 receptors; this, in turn, downregulates the expression of ACE2. Hence, the availability of angiotensin II increases, leading to severe blood pressure fluctuates, especially in patients with a history of hypertension that makes them prone to hemorrhagic stroke[9]. Finally, it is hypothesized that therapeutic targeting of protease-activated receptor (PAR), as a protein engaged in the neuroinflammatory toxicity, may be useful in controlling various complications caused by COVID-19[32].

Table 1 Summary of available evidence-based associations between stroke and coronavirus disease 2019

DIETARY PATTERNS AND STROKE RISK

According to several national studies, nearly 90% of the stroke burden can be assigned to the modifiable risk factors, including poor diet[36,37]. Therefore, a healthy diet is necessary and important as an approved preventive strategy against stroke[22]. Many articles are now available, all of which indicate that healthy eating and adherence to the certain dietary patterns, such as the healthy Nordic diet[23], Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet[22], and especially the Mediterranean diet[24], significantly reduce the risk of both ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes. Hansenet al[23], in their cohort study with a median follow-up period of 13.5 years identifying 2283 cases of stroke, have found that adherence to a healthy Nordic diet (containing fish, apples, pears, cabbages, root vegetables, rye bread, and oatmeal) has a positive effect on stroke risk so that the higher Healthy Nordic Food Index score is associated with a lower risk of total stroke. Clinical trials have also shown that adherence to a healthy Nordic diet leads to weight loss, decreased blood pressure, and improved serum lipid status[38-40]. This diet is rich in potassium and fiber since it contains high amounts of fruits and vegetables associated with decreased blood pressure. Further, high fiber in whole grains is associated with lower total and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. On the other hand, abundant flavonoids in apples, kale, and broccoli are also related to a reduced risk of stroke[23]. The next most examined dietary approach is the DASH diet, which includes a high intake of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat dairy, legumes, nuts, low sodium intake, sweetened beverages, and red/processed meat[22]. A meta-analysis of prospective studies by Fenget al[22]has shown that every 4 points increase in the score of adherence to the DASH diet reduces the risk of stroke in a dose-response manner by 4%. This is true for both ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes, although less data is available on the latter. Randomized clinical trials have also shown that adherence to this diet, in addition to lowering blood pressure, can reduce the stroke risk by improving lipid profile, controlling body weight, besides reducing the risk of type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome, all of which are important in the pathogenesis of stroke[41-45]. Another dietary pattern emphasized to be followed to prevent stroke is the Mediterranean diet. The PREDIMED study[46]with 7447 participants has found that adherence to the traditional Mediterranean diet characterized by high consumption of olive oil, fruits, nuts, vegetables, and cereals, moderate intake of fish and poultry, low intake of dairy products, red meat, and processed/sweetened products, besides moderate consumption of wine, fortified with a mixture of nuts and virgin olive oil for a median of 4.8 years, could reduce the stroke risk by 40% compared to the control. The results of a recent meta-analysis have also shown that any 4 points increase in score of adherence to the Mediterranean dietary pattern in both the Mediterranean and non-Mediterranean populations are significantly associated with a 14% and 17% reduction in the risk of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, respectively[25]. Although the Mediterranean dietary pattern, similar to the DASH, is not a low sodium diet, following this diet high in potassium can probably lead to a reduction in dietary sodium due to the less consumption of processed foods[25]. A newly published cohort study by Chiuet al[47]has demonstrated that a vegetarian diet reduces the risk of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, and higher serum levels of vitamin B12 weaken the relationship. Since a vegetarian diet is a meat and egg free diet, one of the proposed mechanisms is that the adherence to this diet could reduce substrates of intestinal microbiota to produce trimethylamine N-oxide, thus, reduce the platelet hyperactivation and thrombosis functions, and the risk of stroke, consequently[47]. In this study, vitamin B12 deficiency is in favor of a decrease in the incidence of stroke, while other studies are the opposite[48].

Table 2 Summary of available studies related to dietary patterns, some foods, and micronutrients in context of stroke and/or coronavirus disease 2019

DASH: Dietary approaches to stop hypertension; Med-diet: Mediterranean dietary pattern; suppl: supplemented; K: Potassium; Mg: Magnesium; HDL: High density lipoproteins; LDL: Low density lipoproteins; COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019; ACE: Angiotensin-converting enzyme; SARS-CoV-2: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; AIS: Acute ischemic stroke; SCFAs: Short-chain fatty acids; NCD: Normal diet; HFD: High fat diet; PAR: Protease-activated receptor; IL-6: Interleukin-6; CRP: C-reactive protein; Zn: Zinc; Mn: Manganese; Cu: Copper; Se: Selenium.

SOME STUDIED MICRONUTRIENTS OR FOODS AND STROKE RISK

A meta-analysis study has shown that potassium intake significantly inverses association with stroke risk. It is, therefore, recommended to consume potassium-rich foods to support cardiovascular and prevent stroke[49]. The same relationship in a doseresponse manner is true for dietary/supplemental magnesium and total stroke[50]. Moreover, stroke studies have rigorously recommended the protective effect of vitamin D on stroke incidence[51]. Further, other dietary components recommended in the context of stroke incidence have been listed in their work, among which, other than what said thus far, dairy calcium (not supplementation), folate (not supplementation), vitamin C, chocolate, coffee, tea, and the regular and moderate alcohol consumption (not alcohol abuse) are observed[51]. Due to controversy and lack of consensus, there is no recommendation for using B12, folate, and B6 to reduce the risk of stroke, and the results are uncertain[51]. Hence, more studies are needed in this regard.

HOW COULD DIETARY PATTERNS BE ATTRIBUTED TO COVID-19–ASSOCIATED STROKE RISK?

A study has found that countries where the major daily intake originates from uncooked or fermented kale, cabbages, and fermented dairy products known as good sources for anti-ACE activity and rich in antioxidants have lower COVID-19 death rates than the others[52]. ACE converts angiotensin I to angiotensin II, while ACE2 does the opposite in the renin-angiotensin system[52], in addition to being the entry point for SARS-CoV-2 into host cells as mentioned earlier[12,52]. Therefore, in the case of infection with SARS-CoV-2, ACE inhibitors may be effective in improving complications such as high blood pressure and subsequent hemorrhagic stroke[52]. The blood levels of ACE respond very quickly to food intake. Hence, dietary patterns can affect this enzyme levels; thus, it is suggested that a diet rich in saturated fatty acids increases ACE levels[52]. While many functional foods are listed as the ACE inhibitor and antioxidant[53,54]. A recent study has discussed that a healthy, diverse, and balanced diet based on plants, high fiber, and fermented foods rich in the beneficial probiotics, such asBifidobacteriaandLactobacillispecies, could be a preventative strategy, mitigating harmful effects of SARS-CoV-2[20]. Probiotics can modulate the immune system by controlling the gut microbiota, thereby reducing the susceptibility to affliction or morbidity and mortality from COVID-19[20]. Whereas following a high-fat diet and frequent snacks between meals can lead to dysbiosis. Therefore, its frequency should be kept minimum and often include fruits and vegetables[20]. In this respect, interestingly, Tanet al[55]have described that the gut microbiome and the short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) produced by it could regulate brain functions in the path of the gut-brain axis, thus playing a major role in the prevention of stroke. In the study of 140 acute ischemic stroke patients compared with 92 healthy controls, they have observed dysbiosis and low levels of fecal SCFAs in patients with acute ischemic stroke than in controls, inversely related to stroke severity and prognosis. Therefore, SCFAs are introduced as possible prognostic markers and potential targets for stroke remedy[55]. Furthermore, interestingly a few recent studies have discussed the Mediterranean diet and COVID-19[14]. This dietary pattern is anti-inflammatory; it is rich in bioactive components with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties and a variety of vitamins and trace elements but limited in processed foods[14]. Mechanisms involved in reducing stroke following adherence to the Mediterranean diet, which may also be considered for COVID-19–associated stroke, include protection against inflammation, oxidative stress, platelet aggression, endothelial dysfunction, and a pleasant change in metabolites derived from intestinal microbiota that leads to cardiovascular health[25]. On the other hand, as one study suggested, therapeutic targeting of PAR could be promising in the management of COVID-19 neuroinflammatory complications[32]. In this regard, according to an animal study, mice with a high-fat diet (HFD) have higher levels of endogenous thrombin compared to those with a normal diet, being considered as a model for stimulation of PAR-1-based signaling. Whereas β-arrestin-2, unlike thrombin, has a positive effect on this signaling under ischemic stroke condition. HFD mice experience larger infarct and worse outcomes after stroke induction[56]. Therefore, it seems that the role of diet to be also prominent in many signaling pathways related to COVID-19 neuroinflammatory complications. Thus, more human studies in this scope are essential. Apart from nutritional recommendations, due to elevated IL-6 Levels followed by hyperviscosity state[8], it seems necessary to maintain hydration and adequate fluid intake in COVID-19 patients. Altogether, this is important long before and immediately after the COVID-19 pandemic, since long-term and continuous following these healthy dietary patterns, as said, can prevent or reduce comorbidities; this, in turn, may be decrease predisposition to severe COVID-19 and, consequently, its worse complications, such as stroke.

HOW COULD SOME MICRONUTRIENTS OR FOODS BE ATTRIBUTED TO COVID-19–ASSOCIATED STROKE RISK?

Some studies have shown the importance role of potassium and magnesium in COVID-19. Since hypokalemia has been observed in most patients with severe and critical COVID-19[21], potassium-rich foods might also play a supportive role in these patients. Magnesium is also important since it participates in the function of many enzymes involved in the severe immune and inflammatory responses that are manifestations of COVID-19. It, due to its modulator role in IL-6, nuclear factor-kB, and CRP, besides its ability to activate and enhance the function of vitamin D, is essential in preventing the serious consequences of COVID-19 and reducing its morbidity and mortality[21]. In addition to vitamin D, widely discussed due to potential to reduce COVID-19 risk, severity, and mortalityviamechanisms, including inflammation and cytokine storm suppression, besides the inverse modulatory role in the renin-angiotensin system by downregulating renin and increasing ACE2[2,21], other nutrients, such as vitamins, minerals, and functional foods have been discussed in the context of COVID-19. All of these components have also been studied separately concerning stroke. However, no study has ever considered them all together to discuss their association with stroke as a life-threatening complication of COVID-19. For example, some studies have shown that the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency is about 70% among patients with the anti-phospholipid syndrome with elevated levels of anti-phospholipid antibodies. Furthermore, antibodies titers in healthy controls have been lower in the summer season than in other months of the year[2]. This is a fascinating common point in parallel with studies that have shown increased levels of anti-phospholipid antibodies in COVID-19–associated stroke cases[6]. However, the causal relationship between vitamin D levels or supplementation and serum levels of anti-phospholipid antibodies and thrombotic events has not yet been established[2]. Some of the main nutraceuticals and supplements studied thus far on COVID-19 include vitamin E, vitamin D, vitamin C, carotenoids, minerals (Zn, Mn, Cu, and Se), polyphenols, and curcumin. Possible mechanisms of their positive effect on COVID-19 pathways have been proposed as anti-inflammatory, anticoagulant, antioxidant, binding to SARS-CoV-2 target receptor, and antiviral properties[57].

CONSEQUENCES OF THE HYPOTHESIS

The present hypothesis stated for the first time in literature proposes a link between a healthy diet and COVID-19–associated stroke risk. Adherence to healthy dietary patterns and more consumption of some foods and nutrients in the recommended daily allowance has always been flagged as a prevention approach in chronic and acute conditions. Here, it is speculated that such a role of healthy nutrition can be highlighted once again in preventing COVID-19–associated stroke too. Since no study to date has proven this, nutritional intake evaluations or food frequency questionnairebased studies are strongly recommended in order to elicit dietary patterns in COVID-19–associated stroke patients. Also, certain nutrients reported to be effective in common relief functions in stroke and COVID-19 pathways can be prescribed in trials for COVID-19 patients; then, the incidence of stroke in them can be investigated prospectively. If these confirm our hypothesis, it means that healthy nutrition could be a protective/preventive factor against COVID-19–associated stroke risk.

CONCLUSION

Due to the significance of the current pandemic, many studies have paid attention to its consequent clinical outcomes. COVID-19 can be more severe in older patients or individuals with comorbidities, having dangerous consequences, including stroke. Adherence to healthy dietary patterns and more consumption of some foods and nutrients in the recommended daily allowance has always been emphasized as a prevention approach in chronic and acute conditions. However, it should be noted that the present study did not intend to give dietary advice to definite prevention of COVID-19–associated stroke. It only aimed to review the existing literature to evaluate the hypothesis stating that nutrition could be related to COVID-19 and its associated stroke. As far as we know, nutrition cannot be effective in preventing this crisis in the short time, but it can be found that the history of dietary patterns and nutritional intake in patients with stroke or other serious COVID-19–associated complications what is the difference with those in COVID-19 patients without serious complications or even in healthy population by further nutritional intake evaluations or food frequency questionnaire-based studies. If the future studies confirm the present study’s hypothesis (i.e., people who adherence to the healthy dietary patterns and habits are less likely to suffer from severe COVID-19–associated complications such as stroke) the chronic supportive role of a healthy diet in critical situations will be highlighted once again.

World Journal of Meta-Analysis2020年6期

World Journal of Meta-Analysis2020年6期

- World Journal of Meta-Analysis的其它文章

- Comparison of hand-assisted laparoscopic radical gastrectomy and laparoscopic-assisted radical gastrectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Split-dose vs same-day bowel preparation for afternoon colonoscopies: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

- How far has panic buying been studied?