Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in inflammatory bowel disease: The role of chronic inflammation

Simcha Weissman, Preetika Sinh, Tej I Mehta, Rishi K Thaker, Abraham Derman, Caleb Heiberger, Nabeel Qureshi, Viralkumar Amrutiya, Adam Atoot, Maneesh Dave, James H Tabibian

Abstract Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) causes systemic vascular inflammation. The increased risk of venous as well as arterial thromboembolic phenomena in IBD is well established. More recently, a relationship between IBD and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) has been postulated. Systemic inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus, have well characterized cardiac pathologies and treatments that focus on prevention of disease associated ASCVD. The impact of chronic inflammation on ASCVD in IBD remains poorly characterized. This manuscript aims to review and summarize the current literature pertaining to IBD and ASCVD with respect to its pathophysiology and impact of medications in order to encourage further research that can improve understanding and help develop clinical recommendations for prevention and management of ASCVD in patients with IBD.

Key words: Crohn’s disease; Ulcerative colitis; Atherosclerosis; Thromboembolism;Chronic inflammation; Pathophysiology

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic, systemic, relapsing and remitting inflammatory disorder of the gut due to immune and endothelial dysfunction in genetically susceptible hosts[1]. The two main phenotypic patterns of IBD are Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC)[2]. In addition to the primary gastrointestinal manifestations of IBD, a wide-range of extra-intestinal manifestations (EIMs) have also been reported[3,4]. One of the well-recognized EIMs of IBD is the increased risk of thromboembolic phenomena[5-7]. Several recent studies have demonstrated a two to four-fold increased risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) in patients with IBD as compared to the general population[8]. There is growing evidence that atherosclerosis involves dysregulation of innate and adaptive immune systems along with platelet and endothelial dysfunction. Hence, it is believed that the underlying chronic inflammatory process in patients with IBD, similar to other chronic inflammatory disorders, may drive ASCVD risk[9,10]. The goal of this manuscript is to review the association between ASCVD and IBD as well as identify avenues for further research that may help develop clinical recommendations for the management of ASCVD risk in patients with IBD.

ASCVD AS AN EIM OF IBD

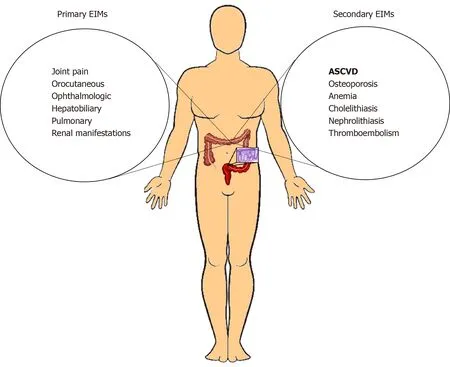

Patients with IBD are exposed to chronic, persistent, systemic inflammation over the course of their lifespan. This predisposes them to a wide range of sequelae across multiple organ systems. The EIMs associated with IBD are traditionally classified as primary and secondary[11]. Primary EIMs include joint, orocutaneous, ophthalmological, hepatobiliary, pulmonary, and renal manifestations (Figure 1). Among these,some parallel IBD disease activity (episcleritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, erythema nodosum, aphthous stomatitis, peripheral arthropathy) and others do not (uveitis,ankylosing spondylitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, alopecia areata, thyroid autoimmune disease). Secondary EIMs are complications related to IBD and include osteoporosis,anemia, cholelithiasis, nephrolithiasis, and thromboembolism (Figure 1)[10].

Figure 1 Illustration summarizing the primary and secondary extra-intestinal manifestations associated with inflammatory bowel disease, including atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease as a more recently recognized secondary extra-intestinal manifestation of inflammatory bowel disease. EIM: Extra-intestinal manifestation; ASCVD: Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

The relationship between IBD and venous thromboembolic phenomena has been well characterized[12-14]. Patients with IBD have a 1.7 to 5.9 times increased risk of venous thromboembolism as compared to the general population[14,15,16]. The underlying pathophysiologic mechanism of thromboembolic phenomena in IBD merits further investigation.

Labeling ASCVD as an EIM of IBD adds valuable understanding to the role of chronic inflammation in the two disease processes. Currently, we do not have enough knowledge regarding the effect of decreasing IBD disease burden on ASCVD and vice versa to categorize it as primary versus secondary EIM. There are no clinical human trials and long-term prospective data to assess whether ASCVD will follow the trajectory of gut inflammation in patients with IBD. Whether there is a specific time point in vascular disease after which reversibility is unachievable needs to be evaluated. The answer to these questions will help us more appropriately place ASCVD in the subcategories of EIM related to IBD. With current knowledge it can be categorized as a secondary EIM (Figure 1).

ASCVD AND IBD

The incidence of ASCVD is increased in patients with IBD as reported by multiple population-based and few retrospective case control studies[17-22]. Indeed, there is a two to four-fold increased risk of myocardial infarction (MI), stroke and heart failure (HF)in patients with IBD. Data from Danish and other European cohort studies, for example have shown an association between ischemic heart disease (IHD) and IBD[17,20-22]. A Canadian study reported an increased risk of IHD (IRR 1.26; 95%CI: 1.11-1.44) and cerebrovascular accidents in patients with IBD (IRR 1.32; 95%CI:1.05–1.66)[22]. Panhwar et al[8]analyzed inpatient and outpatient data from the Unites States and reported a two-fold increased risk of MI in patients with IBD[8].

Some studies and meta-analyses, however, have shown conflicting data[23,24]. Several reasons may account for this; for example, large retrospective cohort studies rely on billing data that are prone to miscoding. In addition, many studies lack data on disease activity and medication use that can influence the inflammatory process and hence the ASCVD events and risk. Studies that have assessed disease activity through indirect measures like steroid use or inpatient admissions have shown a more consistent positive association between the two inflammatory processes[19,20]. A pattern that has emerged over the years shows an increased risk of ASCVD with active disease and in younger and female patients as compared to the general population[9,20]. Notably, there are data showing increased subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with IBD as assessed by modalities such as carotid femoral pulse wave velocity, carotid intimal thickening,and flow-mediated dilatation (FMD)[24,25].

The effect of ASCVD related mortality in patients with IBD is debatable[12,23,26-29]. This can be attributed to multiple factors. Some studies assess mortality over the short duration of inpatient admission that might undermine the effect of long standing chronic inflammation[23,29,30]. Given the increased overall mortality among patients with IBD, it is possible that survivorship and participation bias are obscuring the potential IBD-ASCVD relationship[16]. Some studies lack rigorous matching of the control population[30]. Prospective studies with age matched control groups evaluating the role of IBD medications may be able to better assess the relationship between IBD and ASCVD.

NON-TRADITIONAL RISK FACTORS OF ASCVD IN PATIENTS WITH IBD

Traditional risk factors for ASCVD are age (men > 45 years, women > 55 years), male gender, family history of coronary artery disease (CAD), obesity [body mass index(BMI) > 30], hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, tobacco use, alcohol use, and chronic kidney disease. However, patients with IBD tend to have lower BMI and no significant lipid abnormality[18]. Aspects like age and gender have shown deviation from the general population. Nontraditional risk factors of arterial thromboembolism in patients with IBD merit further investigation.

Role of inflammatory markers

IBD is characterized by high levels of C-reactive protein and various biomarkers that are associated with ASCVD, such as oxidized-low density lipoprotein, fibrinogen,matrix metallopeptidase, nuclear factor kappa-B, and interferon-γ. These are known to cause endothelial dysfunction, platelet aggregation, and hasten the development of ASCVD[31].

In a retrospective case control study, 356 IBD and 712 matched control patients,were assessed with an average follow up time of four and a half years. An increased incidence of ASCVD in patients with IBD despite having a lower burden of traditional risk factors was reported[18]. Furthermore, some non-traditional risk factors, such as white blood cells or perhaps even chronic inflammation, may have had a more robust impact on ASCVD in patients with IBD as compared to the traditional risk factors of hypertension, obesity, and hyperlipidemia[18]. We discuss in this manuscript(pathophysiology section) the biomarkers that link the two disease processes and have the potential for further translational research.

Increased ASCVD with disease activity

A higher risk of venous thromboembolism during active disease is well studied[9]Even though some studies have shown contrary results regarding the relationship between ASCVD and IBD, a consistent pattern of increased incidence of MI during periods of active disease has been evident[12,23,32,33]. A Danish cohort study evaluated 20795 patients with IBD and 199978 matched controls and showed increased risk of MI, stroke, and cardiovascular death during periods of active IBD. During periods of remission, these risks were similar to controls[17]. A French cohort study assessed MI, stroke and peripheral vascular disease in patients 30 days before and after hospital admission,which was taken as a surrogate marker for IBD flare, and found an increased risk of arterial thromboembolic events suggesting the importance of ongoing inflammation and its affect beyond the length of hospital admission[20]. A recent study from Olmsted County, Minnesota, showed an increased risk of MI and HF in patients with IBD with more active and extensive disease[19].

There have been no prospective studies to assess disease activity by stool, blood or clinical markers and correlate it with ASCVD events over short-term or long-term.Most studies have used surrogate markers of inflammation like steroid use,hospitalization or escalation of therapy for disease activity[34]. Studies that measure disease activity and its duration in a prospective manner are needed to better assess the outcomes of ASCVD in patients with IBD.

Increased ASCVD risk in female and younger patients with IBD as compared to the general population

Multiple studies have shown that ASCVD tends to occur in women and younger patients with IBD as compared to the general population[8,35-39]. In a meta-analysis by Sun et al, data from 27 studies showed pooled relative risk for ASCVD, CAD, and MI was 1.25 (95%CI: 1.08-1.44), 1.17 (95%CI: 1.07-1.27) and 1.12 (95%CI: 1.05-1.21),respectively. An association was particularly noted in women with IBD[40]. The metaanalysis by Singh et al[40]identified an overall 19% increased risk of IHD among patients with IBD, however subgroup analysis found the risk among women with IBD to be 26% and the risk among men fell below the level of statistical significance. A Danish population based study that showed an increased risk of IHD in patients with IBD (IRR 1.22, 95%CI: 1.14-1.30) noted that the risk was higher in women (IRR 1.33,95%CI: 1.21- 1.46) and younger patients of age 15-34 years (IRR 1.37, 95%CI: 0.98-1.93)[37]. An Asian cohort study showed that the adjusted hazard ratio for acute coronary syndrome in patients with IBD, compared with controls, was highest in 20 to 39 year age group at 3.28 (95%CI: 1.73-6.22), as compared to the overall risk of 1.70(95%CI: 1.45-1.99)[36]. Recently published study from a large United States database reported higher prevalence of IHD in patients with UC and CD as compared to non-IBD patients [UC 6.9% vs CD 9.0% vs non-IBD 4.0%, OR for UC 2.09 (2.04-2.13), and CD 2.79 (2.74–2.85)]. In this patient cohort, the prevalence of MI was highest among younger patients with IBD[8].

It has been shown that patients with other chronic inflammatory conditions, e.g.,psoriasis, also have evidence of ASCVD at a younger age than general population[38].Younger CD patients have more aggressive disease with more disease burden early during their life and hence it is important to assess their risk of other proinflammatory conditions like atherosclerosis[35]. Investigating and identifying the factors that influence this increased risk (e.g., disease duration and severity) in patients with IBD will help start early intervention with appropriate therapy and thereby decrease inflammatory burden, aimed at long-term risk modification.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY LINKING THE TWO DISEASES

Atherosclerosis is the most common cause of ischemic cardiomyopathy and vascular disease. Chronic inflammation involving the innate and adaptive immune system along with endothelial and platelet dysfunction is present in both atherosclerosis and IBD.

Endothelial cells, lymphocytes, monocytes, macrophages are all involved in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis from formation of foam cells to development of plaque[39,41-44]. Disruption of the endothelium early in the process of atherosclerosis leads to upregulation of adhesion molecules, deposition of lipoproteins in the subendothelial and recruitment of circulating monocytes from the spleen and bone marrow. Some of the adhesions molecules like VCAM1, P-selectin, and ICAM1 are notable in this pathway that lead to expression of chemokines like CCR1, CCR5 and CX3C receptor 1[45-48]. Many of these adhesions’ molecules have been implicated in the pathogenesis of IBD and as potential therapeutic drug targets. Vedolizumab is an antiintegrin molecule that prevents recruitment of white blood cells to the gut by inhibiting binding of α4β7adhesion molecules on the monocytes to the endothelial cells and is widely used to treat CD and UC[49]. Exploring the effect of such medications on ASCVD risk in IBD patients is a potential avenue of research. Further in the process of atherosclerosis, the recruited monocytes differentiate into activated macrophages and take up the apoB containing lipoproteins leading to lipid accumulation and formation of macrophage driven foam cells that overtime lay the foundation of a necrotic lipid core[50-52]. The role of endothelial dysfunction in patients with IBD has been evaluated in a small study through nitric oxide mediated dilatation of the vessels[41]. Endothelial dysfunction as assessed by FMD has been shown to be impaired in patients with active UC[42].

In addition to the innate immune system (macrophages) and endothelial dysfunction (adhesion molecules), the adaptive immune system (T and B lymphocytes,dendritic cells) is involved in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Activation of T helper 1(TH) leads to production of pro-inflammatory cytokines [interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor] that activate local inflammatory cascade[53]. These cytokines are also involved in the pathogenesis of IBD through activation of TH1 and TH17 cells in CD and TH2 cells in UC. The JAK and STAT pathways that act downstream of cytokine mediated lymphocyte activation are implicated in the activation of IL-6 in atherosclerosis and IBD[54]. The JAK inhibitors are being extensively explored as a therapeutic target in IBD and tofacitinib (JAK 1/3 inhibitor) is currently used for treatment of moderate to severe UC[55]. Infliximab and other anti TNF medications are known therapeutic targets in IBD[56,57].

Translational research assessing pathways and cytokines of innate and adaptive immune system and, vascular endothelial dysfunction that are common to both inflammatory processes will help identify biomarkers that can be used to assess, risk stratify and develop focused preventive and treatment modalities to reduce ASCVD risk in patients with IBD.

ASCVD RISK MODIFICATION FROM ANTI-INFLAMMATORY MEDICATIONS

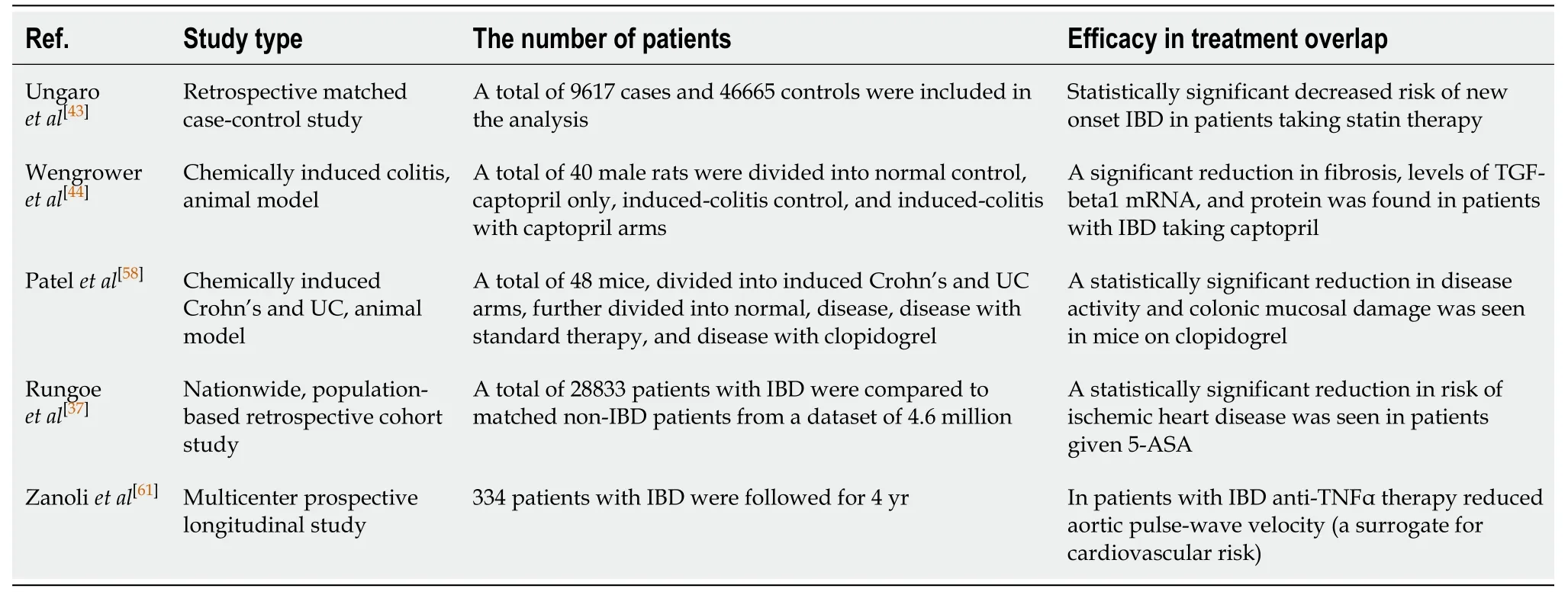

Numerous studies have examined an overlap in treatment between IBD and heart disease, with relative success (Table 1). In a retrospective matched case–control study Ungaro et al[43]assessed statin use in patients with IBD. Statin use was associated with a significantly decreased risk of IBD (OR: 0.68, 95%CI: 0.64-0.72), CD (OR: 0.64, 95%CI:0.59-0.71), and UC (OR: 0.70, 95%CI: 0.65-0.76)[43]. Two studies developed animal models of IBD by chemically inducing CD and UC and showed that captopril was implicated in reducing transforming growth factor-beta1 expression and colitisassociated fibrosis[44,58]. Clopidogrel also reduced disease activity index and colonic mucosal damage index in mice – thus providing an additional link between treatment of IBD and ASCVD[58].

In addition to studies showing benefit for patients with IBD taking ASCVD medications, there have been studies assessing the role of anti-inflammatory medications for ASCVD in the general population. In a multicenter randomized control (CANTOS) trial by Ridker et al[59], canakinumab, a human monoclonal antibody targeted at IL-1, showed a 15% reduction in deaths from heart attacks and strokes combined. Further analysis of the CANTOS trial demonstrated that patients receiving canakinumab that achieved IL-6 levels below 1.65 ng/L had a 32% reduction in major ASCVD events, whereas those at or above 1.65 ng/L received no ASCVD-related benefits[54]. Although there was an increase in fatal infections in the treatment group resulting in no overall mortality benefit, it was clearly illustrated that treatment of inflammation independent of lipid levels resulted in fewer cardiovascular events, and IL-6 could be a potential common mechanism. In addition, a nationwide retrospective cohort study noted that for patients with IBD taking 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), the incidence of IHD was significantly less compared to those not taking 5-ASA[37]. A metaanalysis assessing anti-TNF use in IBD has given us some direction regarding medications that can influence disease activity and ASCVD in patients with IBD[60]. A multicenter prospective longitudinal study in patients with IBD evaluated arterial pulse wave velocity (a surrogate marker of subclinical atherosclerosis) found improvement with long-term anti–TNF therapy suggesting that reduction of inflammation can lead to improvement in endothelial dysfunction[61].

CONCLUSION

Clinicians should be aware of the harmful effects of chronic inflammation on the heart.ASCVD risk is increased among patients with IBD especially during periods of active disease. ASCVD in patients with IBD tends to favor non-traditional risk factors like younger age and female gender. The role of inflammatory markers of IBD as risk factors for ASCVD needs further investigation. Appropriate risk stratification is important in all age groups but especially in those that are diagnosed at an early age and carry the disease burden over a long time. Early escalation of care with more aggressive anti-inflammatory therapy may have a beneficial effect on chronic inflammatory processes like ASCVD, but this needs to be evaluated. Prospective studies assessing the role of IBD medications on ASCVD risk and events will help tailor therapy in patients with IBD based on the mechanism of the drug and subsequently help us move towards personalized medicine.

Table 1 Clinical studies that have found overlap in treatment between inflammatory bowel disease and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease indicating that the underlying chronic inflammatory process in patients with inflammatory bowel disease may drive atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk, and vice versa