Modern surgical strategies for perianal Crohn's disease

Gilmara Pandolfo Zabot, Ornella Cassol, Rogerio Saad-Hossne, Willem Bemelman

Abstract One of the most challenging phenotypes of Crohn’s disease is perianal fistulizing disease (PFCD). It occurs in up to 50% of the patients who also have symptoms in other parts of the gastrointestinal tract, and in 5% of the cases it occurs as the first manifestation. It is associated with severe symptoms, such as pain, fecal incontinence, and a significant reduction in quality of life. The presence of perianal disease in conjunction with Crohn’s disease portends a significantly worse disease course. These patients require close monitoring to identify those at risk of worsening disease, suboptimal biological drug levels, and signs of developing neoplasm. The last 2 decades have seen significant advancements in the management of PFCD. More recently, newer biologics, cell-based therapies, and novel surgical techniques have been introduced in the hope of improved outcomes. However, in refractory cases, many patients face the decision of having a stoma made and/or a proctectomy performed. In this review, we describe modern surgical management and the most recent advances in the management of complex PFCD, which will likely impact clinical practice.

Key Words: Crohn’s disease; Inflammatory bowel disease; Surgical treatment; Perianal fistulas; Anorectal fistula

INTRODUCTION

In Crohn’s disease (CD), perianal symptoms occur in up to 50% of patients with concurrent symptoms involving other portions of the gastrointestinal tract; in 5% of cases, perianal symptoms occur as the first manifestation of CD[1]. A challenging phenotype of CD is perianal fistulizing CD (PFCD), an aggressive, debilitating condition associated with significant morbidity that can negatively affect quality of life[2]. Treatment is difficult, often requiring more aggressive medical and surgical interventions than luminal disease. In addition, it predicts a worse disease course, requiring rigorous monitoring to identify those who are at risk of worsening, suboptimal levels of biological drugs, and signs of neoplasia[3].

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Although the pathophysiology of cryptoglandular fistulas is well understood, that of CD-related fistulas has not yet been defined. Some theories have been proposed, but none have been confirmed[4].

CLASSIFICATION

Historically, perianal fistulas have been classified according to Parks’ anatomical model[5]. However, the American Gastroenterology Association has proposed that PFCDs should be classified into 2 categories: Simple and complex (i.e., those with a high internal orifice and multiple or rectovaginal fistulas associated with abscesses or stenosis)[6]. The Van Assche score assesses the severity of CD throughout the anal canal based on magnetic resonance imaging findings[7].

The treatment of PFCD has traditionally been surgical, and seton placement is the most common technique. However, with the advent of biological therapy, especially anti-TNF agents (infliximab and adalimumab), the approach to these fistulas has changed. Thus, this article aims to review the currently available methods for managing PFCD.

TREATMENT OF PERIANAL FISTULAS IN CD

The initial approach is to control sepsis and take measures to prevent recurrent abscesses and the appearance of additional tracts by seton placement. Cutting setons should be avoided due to the risk of fecal incontinence[8].

SIMPLE FISTULAS

Fistulotomy is appropriate for superficial or low transsphincteric fistulas without associated proctitis, in addition to subanodermal, submucosal and subcutaneous fistulas. The recurrence rate is low (< 10%)[8]. However, incontinence rates vary from 0% to 50%, which leads to conservative techniques, such as seton placement[4]. Fistulotomy should not be performed anteriorly due to the risk of keyhole defects at the site where the sphincter is shortest, particularly in women. In the presence of proctitis, the fistulotomy wounds might not heal.

COMPLEX FISTULAS

Complex fistulas require an average of 6 procedures, while simple fistulas require 3 procedures[4]. At 10 years of follow-up, one-third require diversion and 13% require a proctectomy[9].

TREATMENT OPTIONS FOR COMPLEX FISTULAS

Long-term setons

Non-cutting setons can be maintained long term,i.e., months or years. Two issues remain controversial during combination therapy (anti-TNF): Timing of withdrawal and number of procedures. The absence of secretion and proctitis are important factors. According to GETECCU recommendations, it is the option of choice in the presence of proctitis[10]. Kotzeet al[11]found that the average time until seton removal was 7.3 mo, ranging from 1 to 36 mo. The advantages of this technique are the low cost, the prevention of new abscesses or recurring tracts, and a decreased need for temporary or permanent stoma, in addition to the low rate of reintervention (10% to 20%)[8]. On the other hand, the fistula does not close with the setonin situ, and the rate of clinical closure of the fistula after removal is 42% when used alone and 64% when in combination therapy with anti-TNF[12]. Another issue to be addressed is patient quality of life. The seton should be removed if the treatment goal is to close the fistula, usually prior to the end of the induction phase of TNF-inhibitors[13,14](Table 1)[15-18].

Endorectal advancement flap

For endorectal advancement flap procedures, a tissue flap is mobilized from the mucosa, submucosa, or circular muscle layer of the rectum and advanced to cover the fistula’s internal opening, resulting in an intact sphincter apparatus. Healing of the excluded fistula pathway is expected over time. In the absence of proctitis or stenosis, this is a good therapeutic option with the advantage of avoiding extensive or difficultto-heal wounds and a success rate of approximately 50%[10,19](Table 2)[20-25].

The ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract

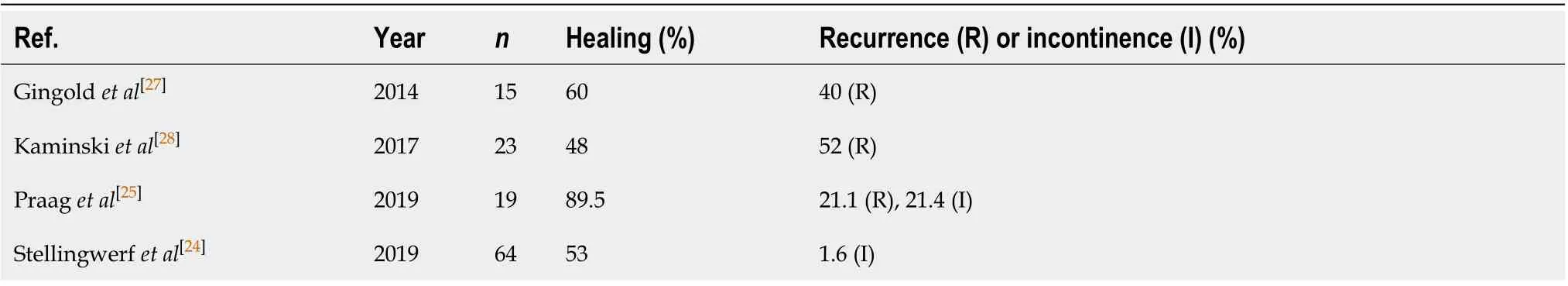

The procedure for ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT) involves the ligation and removal of the fistula pathwayviathe intersphincteric space, followed by removal of the remaining fistulous tract by curettage and closure of the defect by suture in the external sphincter[26], so that the sphincter is not affected[27]. Kamińskiet al[28]followed 23 patients with transsphincteric fistulas due to CD who were treated with LIFT. After 23 mo the healing rate was 48%. However, most reports of LIFT procedures describe patients without CD, and only a few studies have been published exclusively on PFCD treatment.

In CD, patients without proctitis who have lateral fistulas with long tracks, previous seton treatment, and small intestine disease would be the best candidates for the LIFT procedure. However, prospective randomized studies comparing LIFT to other techniques are needed to define the role of this method in the treatment algorithm for PFCD[29](Table 3)[24,25,27,28].

Fibrin glue and plugs

Two anal fistula plugs are frequently used in the management of perianal fistulas: The Surgisis (Cook Surgical, Bloomington, IN, United States), a bioabsorbable xenograft made of lyophilized porcine intestinal submucosa; and the GORE (Bio-A; WL Gore and Associates, Flagstaff, AZ, United States), a synthetic plug made of polyglycolic acid and trimethylene carbonate, which contains 2 absorbable synthetic materials inthe fistula path that allow fixation to the fistula’s internal opening[13]. The basic principle of the plug's action is to occlude the fistula path and promote healing. A controlled, randomized, multicenter study by the GETAID group compared the removal of the seton alone (control group) with plug insertion and found a healing rate of 31.5% in the plug group and 23.1% in the group control[30].

Table 1 The results of long-term seton procedures

Table 2 The results of flap procedures

Table 3 The results of ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract procedures

Heterologous fibrin glue is a 2-component material whose first component consists of fibrinogen, factor XIII, plasminogen, and aprotinin, whereas the second component consists purely of human thrombin. Simultaneous injection of the 2 components creates a fibrin clot that will mechanically seal the fistula path. Grimaudet al[31]conducted the first randomized, controlled clinical trial using fibrin glue to treat PFCD. They found healing rates of 38% in the glue group and 16% in the control group[31]. With unfavorable results for PFCD healing, both techniques were abandoned[4](Table 4)[32-36].

Video-assisted anal fistula treatment

The main steps in Video-assisted anal fistula treatment (VAAFT) include excision of the fistula’s external orifice, insertion of a fistuloscope to visualize the main and secondary pathways, correction of the location of the internal orifice under direct vision and irrigation, followed by electrocauterization of the paths. Schwander, the first author to demonstrate the results of VAAFT through a prospective, randomized study, compared the results of the VAAFT with the endorectal advancement flap technique. After a 9-mo follow-up, the success rate was 82% (9/11)[37]. Since this is a high-cost method with a long learning curve, the results of long-term studies are necessary[10,28](Table 5)[37-40].

Table 4 The results of fibrin glue and plug procedures

Table 5 The results of video-assisted anal fistula treatment procedures

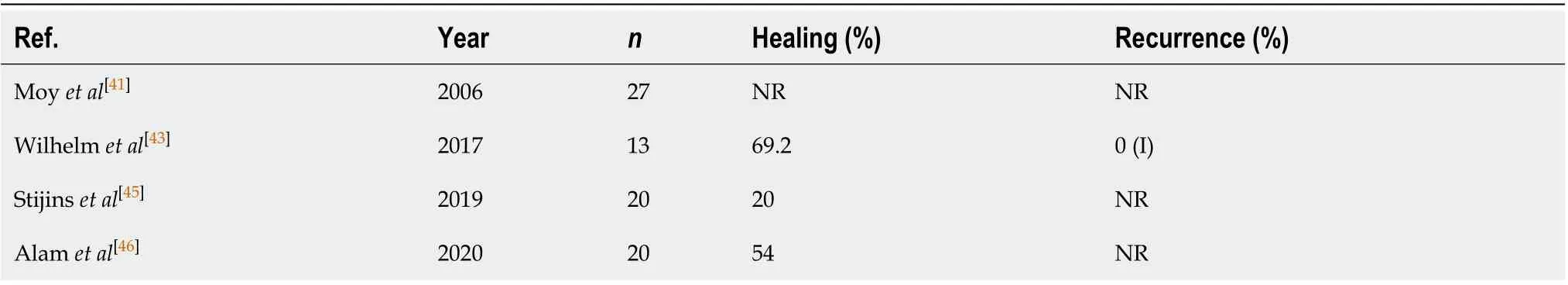

Fistula-tract Laser Closure

Lasers were first described in perianal fistula treatment in 2006. A carbon dioxide laser was used in 27 patients with CD, and most improved[41]. In 2011, Wilhelm described a new surgical technique using a radial laser probe [Fistula-tract Laser Closure (FiLaCTM), Biolitec AG, Jena, Germany] to treat PFCD[42]. The basic principle of this technique is to destroy the epithelium of the fistulous path with the laser, although without direct visualization. In the initial study with this technique the internal orifice was closed with advancement of the endorectal flap. Wilhelm recently performed a for 2-year follow-up of 13 patients who underwent FiLaC combined with endorectal advancement flap and observed a 69% primary healing rate, which rose to 92% after the second surgery (secondary healing)[43]. The main advantages of this procedure are a shorter learning curve compared to VAAFT, faster recovery, and preservation of the sphincter. The disadvantages are the cost of the equipment and the absence of direct visualization of the paths. Thus, secondary paths may not be visualized and the healing rate could be reduced[29].

A recently published systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that FiLaC can be considered an effective and safe sphincter preservation technique with low complication rates. However, the review emphasized that studies comparing the laser to other techniques will be necessary to substantiate these promising results[44](Table 6)[41,43,45,46].

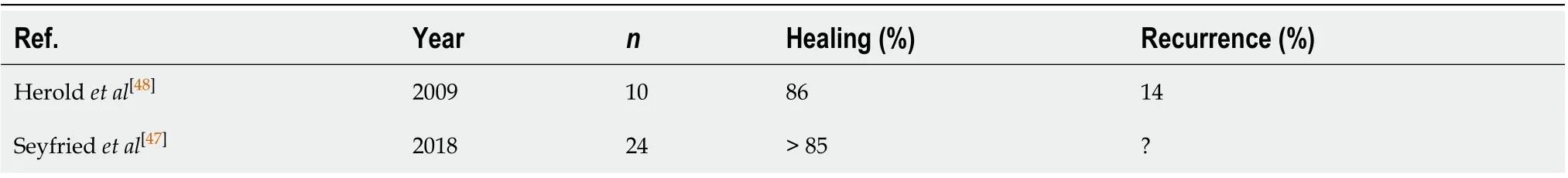

Fistulectomy with primary sphincter reconstruction

Recent retrospective studies have assessed fistulectomy with primary sphincter reconstruction, finding excellent results. After an average follow-up of 11 mo (7 to 200 mo), the primary healing rate was 88.2%, with low recurrence rates[47]. However, no prospective studies have been published yet[28](Table 7)[47,48].

Stem cell injection

The use of mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) is the most recent and promising strategy in PFCD treatment. MSC are a cell population similar to fibroblasts that can differentiate into several mesodermal cell lines[5]. They have potent anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activity[49]. The use of MSC in PFCD treatment is supported by the hypothesis that epithelial defects give rise to fistulas, which are maintained open by continuous inflammation occurring along the path. Injection of MSC into the fistula pathway is believed to reduce inflammation, thus promoting its healing[3]. MSC may be derived from adipose system (adipose stem cells – ASC) or from bone marrow. Despite the lack of clinical trials comparing bone marrow MSC to ASC, there are some reports of potential advantages of using ASC. Liposuction or excisional fat biopsy canbe used to ensure the harvest of a large number of stable raw cells that are readily available for clinical use. ASC also have a greater proliferative and angiogenic capacity, in addition to being more genetically and morphologically stable[5]. However, to date, no study has directly compared the use of autologousvsallogeneic MSC. It may take several weeks to expand autologous MSCin vitro. In addition, the patient's age and disease status can also affect cell quality. Nevertheless, allogeneic therapy with MSC has gained increasing popularity because of the immediate availability of high-quality cells for treatment. Thus, allogeneic products are likely to be used in the future[50].

Table 6 The results of fistula-tract laser closure procedures

Table 7 The results of fistulectomy with primary sphincter reconstruction

Evidence about the effectiveness of ASC for complex PFCD treatment comes mainly from the ADMIRE-CD, a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 212 patients who did not respond to conventional medical treatment and were randomly assigned to receive an injection of 120 million ASC into the fistula pathways or placebo. Patients were allowed concomitant treatment with immunosuppressants and/or anti-TNFs at stable doses throughout the study. Combined remission at week 24 was the primary endpoint, defined as the clinical closure of all treated fistulas (absence of draining), as assessed by gentle finger compression, and absence of collections > 2 cm on magnetic resonance imaging. Significantly better results were obtained for combined remission in the ASC group than in the control group (50%vs34%,P= 0.024)[51].

The STOMP study, conducted by the Mayo Clinic, was the first study to report the use of autologous ASC in a bioabsorbable matrix for the treatment of patients with a single fistula and no associated proctitis who did not respond to anti-TNF therapy. At 3 mo, 9 of the 12 patients (75%) had complete clinical healing, while at 6 mo 10 patients (83.3%) did, with similar rates of remission found in magnetic resonance imaging[52].

Injecting stem cells may be a valid alternative for complex PFCD that cannot be treated by conventional surgical methods. More evidence is required from adequately powered randomized clinical trials.

PISA trial

The PISA trial was a multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled study comparing 3 groups: One that received a long-term seton (1 year), one that received anti-TNFs for 1 year, and a third that underwent surgical closure of the PFCD with either an endorectal advancement flap or LIFT, after 2 mo of anti-TNF. Before randomization, all patients underwent seton placement under general anesthesia, received antibiotics (metronidazole) for 2 wk and 6-mercaptopurine. The results showed a higher rate of reintervention for the long-term group seton group (10/15vs6/15 anti-TNFvs3/14 surgical closure). The results suggest that chronic treatment with a long-term seton cannot be recommended as the only treatment for PFCD[12].

Endoscopic therapy for perianal disease

Partial endoscopic fistulotomy can be performed on intersphincteric fistulas through incision and endoscopic drainage. Although incision and endoscopic drainage can also be performed with PFCD-associated perianal abscesses, it would be a temporary measure since more definitive therapy is needed, such as seton placement or fistulotomy. Abscesses associated with a perianal fistula can also be treated with endoscopy-guided seton placement[29,49].

Intralesional anti-TNF

In 7 case series, all with a small sample size (from 9 to 33 patients), infliximab (15 and 25 mg every 4 wk) or adalimumab (20 or 40 mg every 2 wk) was injected locally around the fistula, and closure was reported in 31%-75% of cases. The advantage is that injections can be easily repeated[10]. In a recent review evaluating 6 case series (including 2 studies with adalimumab injection), for a total of 92 patients enrolled, short-term efficacy (defined as complete or partial response) ranged from 40% to 100% without any significant adverse events[53]. Although local injection of infliximab appears to be safe and possibly effective, these studies involved few patients, had a short follow-up and no control group, in addition to a lack of standardization of the evaluated criteria and results.

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy

It has been proposed that hypoxia contributes to the onset and maintenance of inflammation, either as a causative or modifying factor, and its role as a trigger of inflammation has been demonstrated bothin vitroandin vivo. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (i.e., inhaling pure oxygen in chambers at pressure > 1 atm) provides an option to optimize fibroblast proliferation and leukocyte activity[49], as well as to reduce hypoxia duration by altering the secretion of interleukin 1 (IL-1), IL-6, IL-2, and TNF and promoting angiogenesis. This technique has been effectively used to treat perianal disease, pyoderma gangrenosum, steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis, and persistent perineal sinus following proctectomy in inflammatory bowel disease. Regarding response to hyperbaric oxygen therapy among patients with perineal or fistulizing CD, rates range from 50% to 70% for complete response, from 9% to 41% for partial response, and from 12% to 20% for no response; a response rate of 88% has been reported in a systematic review of 40 patients with perianal disease refractory to conventional therapy[49,54,55].

Mild adverse effects have been associated with hyperbaric oxygen therapy, and they appear to be related to alterations in oxygen toxicity and barometric pressure. Trauma to the middle ear or sinus is reported as the most common complication, whereas rare complications have been observed in patients with underlying pulmonary disease and include pneumothorax, air embolism, and transient vision loss. Cataract maturation has been reported in more than 150 treated patients[49,56].

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy may be suggested as a last-line option in the treatment of chronic perianal CD refractory to other therapies or as an adjuvant to surgery, but controlled trials are still needed before it can be recommended for the management of PFCD[10]. This treatment is very time consuming and the effect might not continue if treatment is stopped.

Deviation

Deviation is a therapeutic option for patients with refractory perianal CD. However, due to its temporary character, it is not always feasible. In a systematic review including 15 studies, for a total of 556 patients enrolled, a low rate (33%) of intestinal transit reconstruction was observed after deviation[57].

Proctectomy

Proctectomy is the final treatment option for severe perianal CD refractory to aggressive medical treatment and to surgery. Proctocolectomy is preferred to rectal preservation in patients with concurrent Crohn's colitis and perineal disease because of the high rate of persistent rectal stump disease in cases in which the stump is left in place[4]. A feared complication after these techniques is inadequate healing of the perineal wound or the emergence of a perineal sinus of persistent drainage[58]. Proctectomy must include the mesorectum, since proinflammatory cells in the Crohn’s mesorectum might fuel persistent inflammation in the pelvis. The cavity produced after a TME-type proctectomy can be filled with omentum[59].

A preoperative diagnosis of CD is generally considered a contraindication to ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA), although restorative proctocolectomy with the IPAA technique is a possibility in some Crohn’s colitis patients. No significant difference was found in pouch failure between CD and ulcerative colitis[60]. Liet al[61]suggested a very select group of patients in whom surgery may be an appropriate treatment: Those without perianal, small bowel, or mesenteric disease. Shenet al[62], on the other hand, reported that patients with a preoperative diagnosis of CD who undergo IPAA often develop CD in the pouch after surgery. Multicenter studies with a large number of patients will be necessary to better define indications for IPAA in CD.

CONCLUSION

Although medical treatment is the basic approach to perianal CD, surgical treatment is also essential. Before treating the fistula medically or surgically, a seton must be placed. However, there is still no consensus about the best approach. There is no doubt that, in the presence of serious or recurrent disease, aggressive surgical treatment should be considered. In addition, some patients will require a stoma or even a proctectomy. In cases of deviation, always consider closure after controlling for proctitis. It should also be noted that perianal CD should be managed by a multidisciplinary team.

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年42期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年42期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in lean subjects: Prognosis, outcomes and management

- Simultaneous colorectal and parenchymal-sparing liver resection for advanced colorectal carcinoma with synchronous liver metastases: Between conventional and mini-invasive approaches

- Estimation of visceral fat is useful for the diagnosis of significant fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- Nomograms and risk score models for predicting survival in rectal cancer patients with neoadjuvant therapy

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and gastrointestinal morbidity in a large cohort of young adults

- Reactive oxygen species-induced activation of Yes-associated protein-1 through the c-Myc pathway is a therapeutic target in hepatocellular carcinom