Screening for scoliosis - New recommendations,old dilemmas,no straight solutions

Abstract

Key Words:Scoliosis; Screening; Tests; Programs; Recommendations; Guidelines;Principles; Benefits; Harms; Trustworthiness

INTRODUCTION

In this opinion review we will contribute to the discussion related to the prevailing question whether “to screen or not to screen for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis”[1-4].We discuss the process of screening for scoliosis as it can be perceived today.Specifically,we present a crucial,but understated,issue of understanding and implementation of the contemporary principles of person-centred care,standards of preventive screening,and guideline development,in the context of screening for scoliosis.

On one hand,new and improved standards of people-oriented care and personcentredness have been postulated and implemented in health care systems and cultures[5-7].New and improved principles of preventive screening[1,8,9]and guideline trustworthiness[10-13]have been introduced.On the other hand,health care systems and societies face dangers of overdiagnosis[14-17]and unnecessary treatment[17-19],as well as of distrust in evidence-based medicine[20,21]and of disease mongering[17,18,22].

School screening for scoliosis was introduced in the United States in the 1960s[23].The earliest,as it is called today,evidence-based recommendations on population screening,were released in Canada in 1979[24,25].Since then,different guidelines,policies and statements were produced worldwide[24-26].

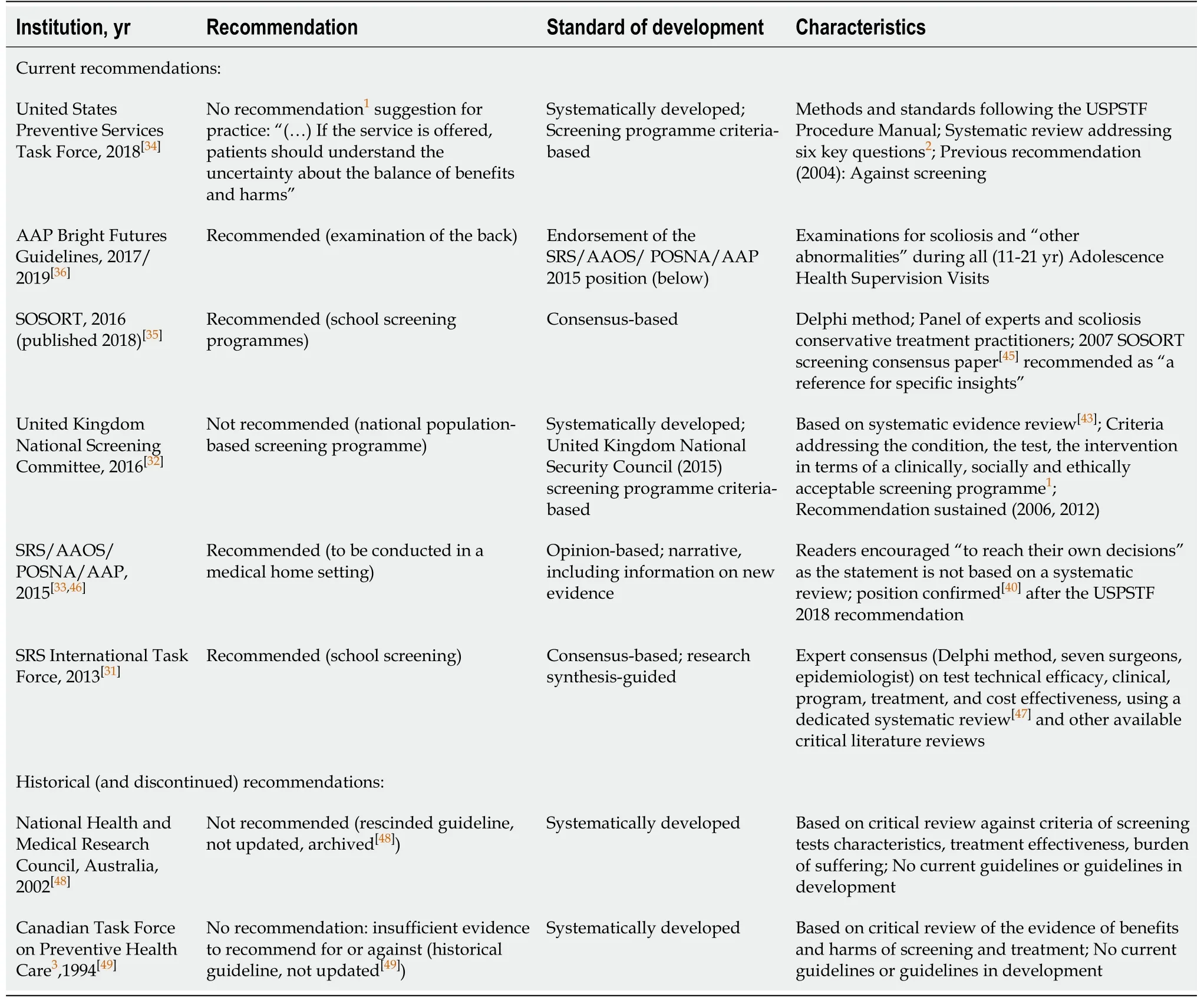

In the last decade,in the new era of guideline development[10-12,27,28],and after screening principles have evolved significantly[1,8,9,29,30],a number of updated and new recommendations and statements on screening for scoliosis[31-35],as well as on periodic examination of the spine[36],have been released.Nonetheless,the dilemmas prevail[37-39]and consensus does not seem to be reached[40,41].Internationally,recommendations differ substantially,not only in terms of their content,but also standards of development and screening principles.Some countries have discontinued issuing recommendations addressing screening for scoliosis[24,25].The evidence base for recommendation formulation is surprisingly limited[25,26,42-44].The variations continue(Table 1)[45-49].

In the United Kingdom,screening for scoliosis is not recommended since the 1980s[50].The United Kingdom National Screening Committee consequently recommends against screening[25,32],based on their set of principles,introduced in the early 2000s[1].The Canadian Preventive Task Force on Preventive Health Care have not released any recommendation update since their 1994 recommendation against screening for scoliosis[24,25,49].The Australian National Health and Medical Research Council,also operating on the basis of their advanced standards of guideline development[51],have archived their latest (2002) recommendations against screening[48]and do not continue releasing any new recommendations.The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF),have changed their recommendation from“no recommendation” in the 1990s[24,25],through a 2004 recommendation against screening[24,25]and,most recently,to a statement of insufficient evidence to formulate any recommendations[34].Their key “I” recommendations are reported to the United States Congress[52].Orthopaedic and rehabilitation organisations tend to support screening[31,33,35,46](Table 1).

Consequently,the state of affairs in the United States remains peculiar.AmericanAcademy of Family Physicians follow the USPSTF recommendations[53,54],whereas American Academy of Paediatrics endorse the Scoliosis Research Society (SRS)/American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS)/Pediatric Orthopedic Society of North America (POSNA) statements[46,55].There is no national policy school screenings are mandatory,optional or are discontinued in individual States[56,57].

Table1 Major current and historical recommendations about screening for scoliosis

The arguments concentrate on the issues of the need for early detection through screening,the effectiveness of early (conservative,especially bracing) treatment,and consequent reduced surgery rate[33,35,40,46,55],on costs of screening procedures and costeffectiveness of screening programmes[31,47,58],as well as on scientific and epidemiologic value of screenings[45,59]and the credibility of the sources of evidence[26,43,44,60].Nonetheless,systematically developed guidelines and recommendations are confronted by consensus and opinion based statements (Table 1).

The trust in expert opinions,rather than in systematically developed guidelines and recommendations,seems to be related to the scepticism,or unfamiliarity with the principles of evidence-based practice,and about the importance of its implementation[20,21].In our view,however,it is also a matter of understanding and implementation of the contemporary principles and standards of screening (while both issues are very much related).We propose a discussion around screening for scoliosis put in this context.

The problem matter is of global scale[24,38],applies to millions of people[61-63],and screening programmes have usually been school-based[26].It regards clinical and methodological dilemmas,but also the matter of vulnerable and fragile time of adolescence[64]and,more generally,the matter of preserving children’s rights[65].The decisions need to integrate people’s values and preferences[1,7,9,16,28]– screening tests need to be acceptable to the population,and treatments need to be acceptable for patients[1,9,28,29].

PEOPLE-CENTRED CARE

The World Health Organisation’s Global Strategy of Integrated People-centred Health Services 2016-2026 underpins that people and communities need to be placed at the centre of health services,with terms and actions such as people-centred care,personcentred care and engagement,representing this philosophy[5,66].

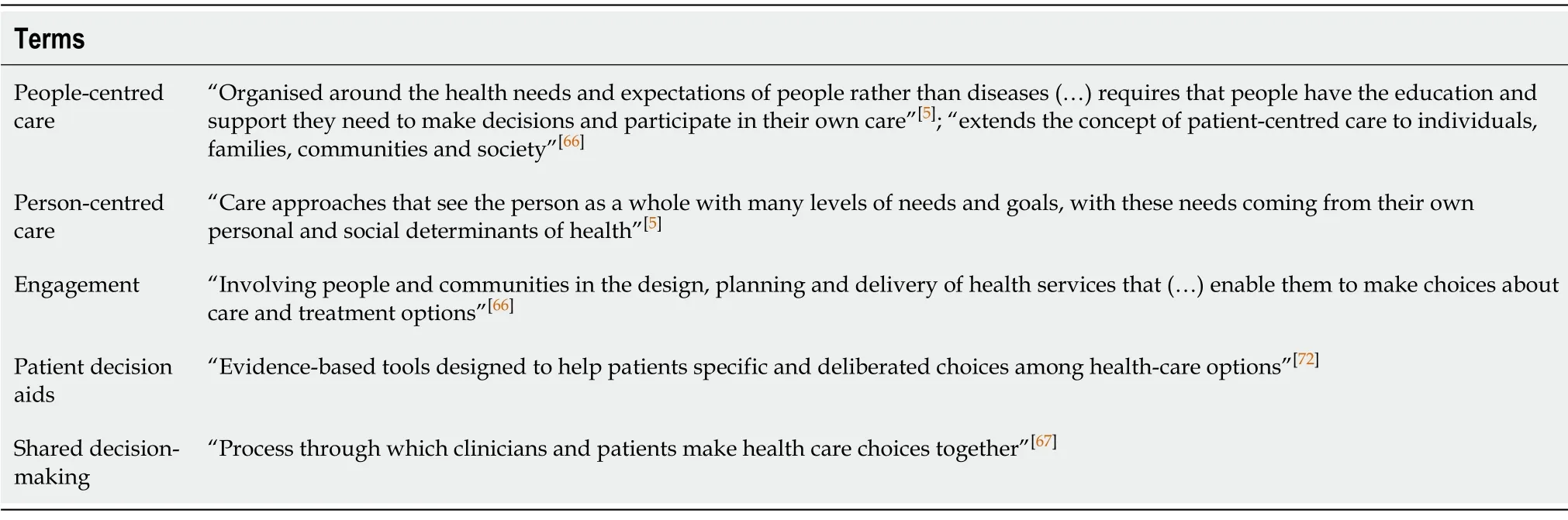

Shared decision making is the core of people-centred care[6,7,67-69].Decisions need to be grounded in patients’ values and perspectives[5-7,67,68],as engaging patients in making choices and decisions leads to better health outcomes and better healthcare experiences[6,68,70,71].Standardised information,such as patient decision aids,are replacing traditional educational and information tools,as the way clinicians provide information may strongly affect people’s preferences[72,73].We summarise those key terms in Table 2.

GUIDELINE DEVELOPMENT AND RECOMMENDATION FORMULATION TODAY

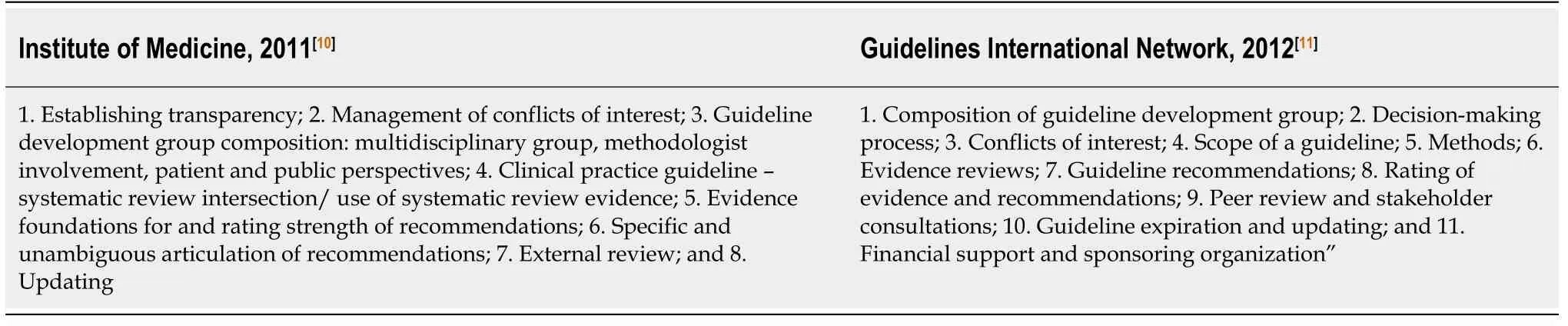

Standards of guideline development and recommendation formulation have been improved in recent years[10-12,27](Table 3).Based on the Institute of Medicine standards of guideline development[10],guidelines not based on systematic review of the evidence were no longer included in the National Guideline Clearinghouse database[13].

Contemporary sets of criteria for trustworthy guidelines do not duplicate,but control for conflicts of interests,multidisciplinary guideline development group composition,public engagement,shared decision making and respecting people’s voices are their common features[10,11,27,74,75].Interestingly,these have been postulated by the Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group specifically addressing guidelines and recommendations about screening as early as in 1999[28](Table 4).

EVOLUTION OF SCREENING PRINCIPLES

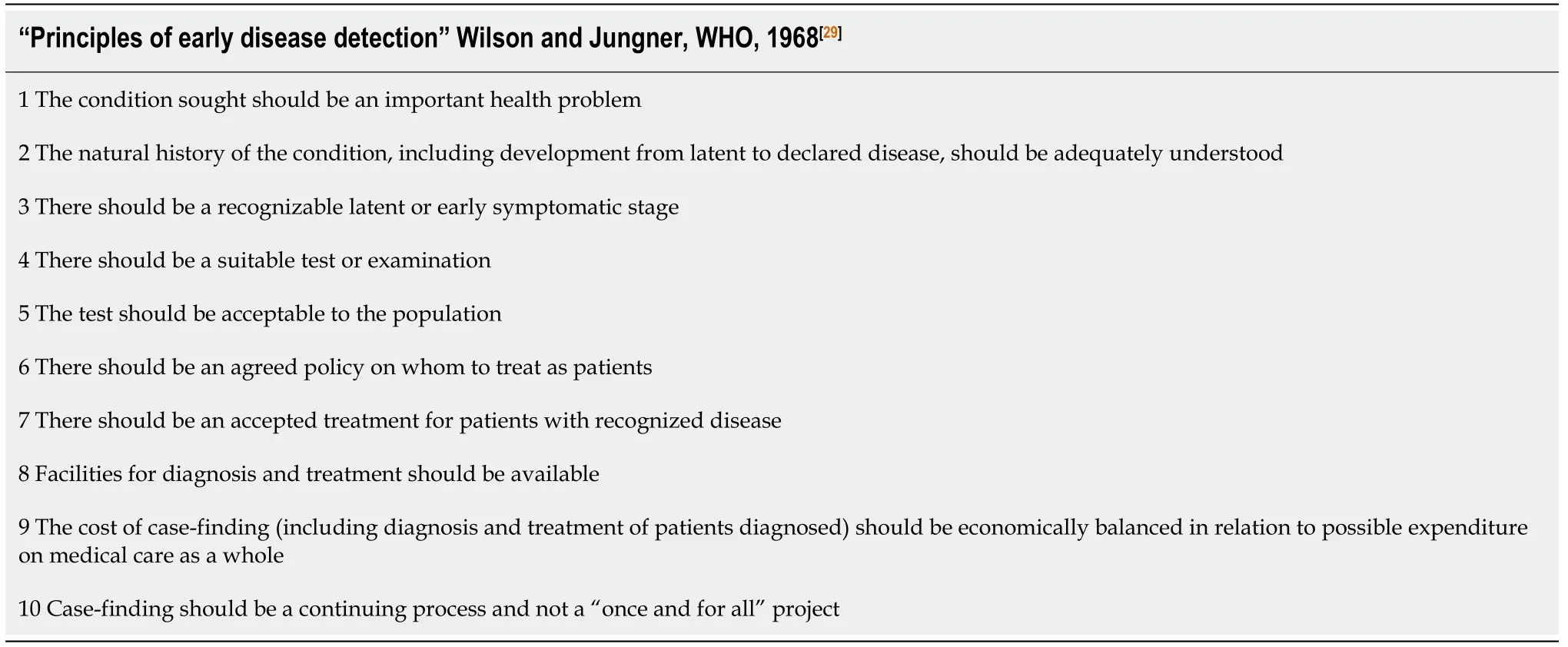

The 1968 World Health Organisation’s “Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease”[29](Table 5) have become the gold standard[1,9,30],and are still used as a frame of reference[9,47].

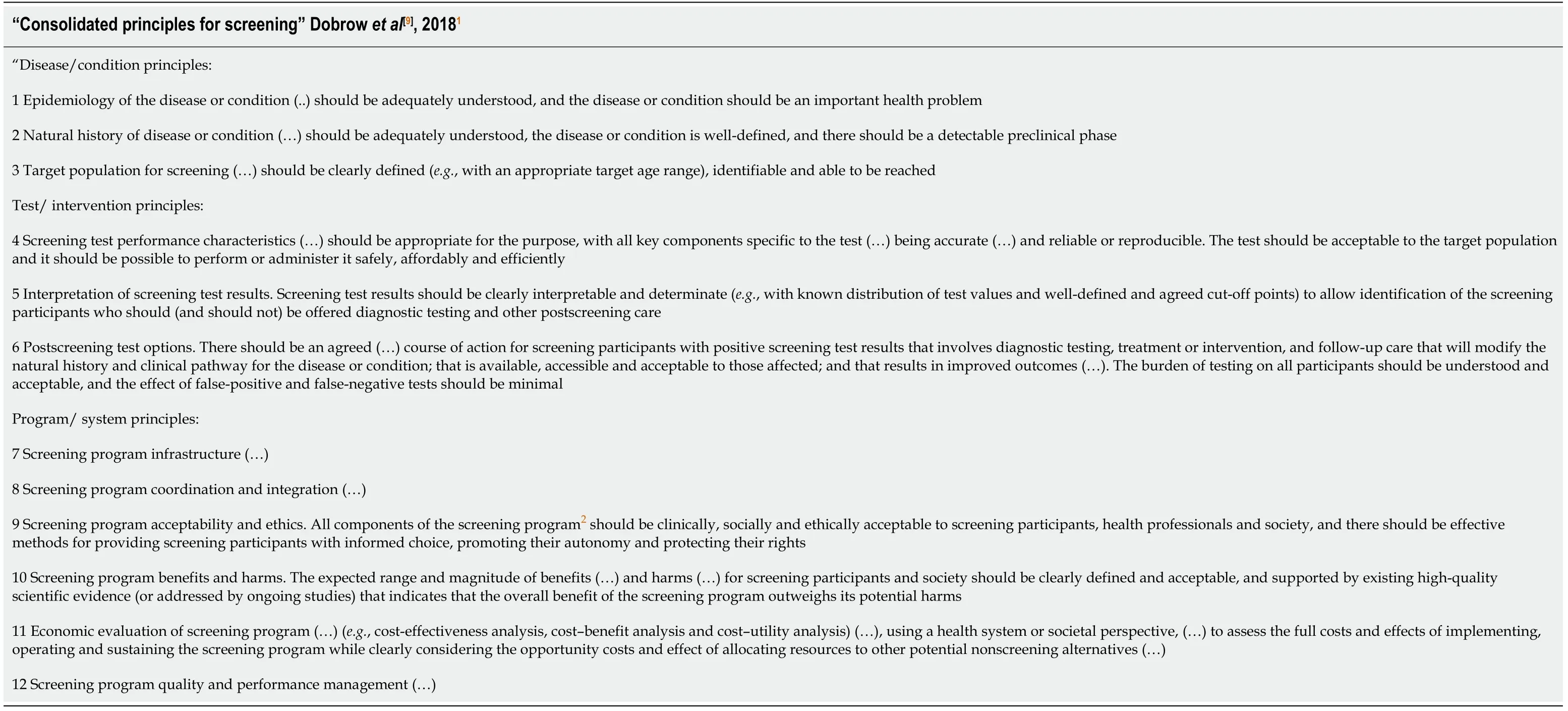

Nonetheless,the understanding,principles,and criteria of screening have evolved over the years,and numerous proposals and policies have been formulated[1,8,30]and introduced[26,43,48,49].A recent synthesis study located 41 sets of standards and 367 screening principles[9](Table 6).

In contrast with the Wilson and Jungner’s “screening for disease”[29](Table 5),defining screening as secondary prevention (early disease detection),contemporarily screening is defined as preventive service,covering all stages of management,from prevention,through diagnostics,to treatment[1,8,9,16,28](Table 6).

Harriset al[8]propose to introduce the term ‘‘predictor of poor health’’ to emphasize a focus on health outcomes[8].The terminology shifted from “asymptomatic subjects”[24,25]to “otherwise healthy individuals”[75].(“It is sometimes useful,we think,to use a term that refers to all forms of early detection whether by screening,physical examination or other means; and this is meant when we use the term "early disease detection”[29].“The purpose of screening is to improve the length and/or quality of people’s lives,not just to find abnormalities”[8]).

Importantly,however,Wilson and Jungner postulated that both the treatment and the test need to be acceptable to the population,and that the first aim is to avoid harms to the patients[29].The underpinning principle is that screening may be beneficial,but it can also be harmful[1,8,9,28].[“In adhering to the principle of avoiding harm to the patientat all costs (the primum non nocere of Hippocrates),treatment must be the first aim”[29]].

Table2 Terms related to people-centred care and person-centred care

Table3 Generic standards of trustworthiness for guidelines and recommendations

Table4 Screening-addressed standards of trustworthiness for guidelines and recommendations

HARMS OF SCREENING

Problems of potential harms of screening,such as overdiagnosis and unnecessary treatment,have gained much attention recently[14-17].These concerns correspond with the debate on widening the definitions of diseases,narrowing the definition of health,with medicalisation of unpleasant experiences of everyday life[17,18],and presenting presymptomatic,early or minor problems as serious conditions[17-19,22].Another potential driving factor for overdiagnosis and unnecessary treatment is using a common term – label of a single “disease” – for a heterogeneity of conditions of wide spectrum of health outcomes[17,18,76-78],and the phenomena of “apparent illness”[17],attributed to overdetection due to increased testing and improved diagnostic tools,rather than a real change in the incidence of illness[16,18,76,77].

Table5 Wilson and Jungner screening principles,World Health Organization 1968[29]

Calls for renaming low risk conditions labelled as cancers[78]and the “tripling of the incidence of thyroid cancer,with unchanged death rate”[17],are striking examples,but analogies to adolescent idiopathic scoliosis,both in terms of the progression of the condition,as well as severity and a very wide spectrum of potential health outcomes,are also noticeable.In Table 7,we summarise the drivers of “too much medicine”[14,17,18,77]and present our view of corresponding issues regarding screening for scoliosis.

Screening programmes are recognised as justified when they address conditions which would lead to earlier death or significant decline in health if a condition is not detected through screening[1,9,14,16,77].

A proposed screening programme need to be evaluated against evidence on the magnitude of health benefits,but also against the evidence on the magnitude of health harms.The factors on the harms side of the screening balance are the frequency of false-positive tests,the frequency of overdiagnosis,and the experience of overdiagnosed people (Table 7)[79-81],considered in relation to the magnitude(frequency and severity) of harm[1,8,9,14,77].

Harms are no longer understood purely in terms of direct adverse events or side effects of diagnostic testing (such as x-ray exposure[26,43]) and of treatment (such as skin irritation by a brace[82]).They are meant as the value of health lost due to the overdiagnosed or false-positive health state,such as anxiety and complications of labelling,diagnostics,unneeded or unnecessary treatment,and stigmatisation[1,8,9,16,18].

“The experience of overdiagnosis (…) often life-changing,(…) includes unnecessary psychological and physical effects from labeling,diagnostic evaluation,and treatment,(…) is itself associated with harm”[8].

UPDATED RECOMMENDATIONS,OUTDATED STANDARDS?

Disputes over screening for scoliosis have focused on the condition-specific arguments,such as the need for early detection and treatment,and the evidence for the effectiveness of nonsurgical treatment,in terms of avoiding the need for surgery.Less attention is paid to the dispute regarding the evolving generic concepts,standards and principles of screening.

People-centredness

Decisions about treatment (and screening) options are considered “preferencesensitive” because of insufficient evidence about the outcomes and because a trade-off between known benefits and harms is needed[26].Individual people do not necessarily benefit from treatments,even if they show beneficial effects for populations[1,8,71].People differ in their judgements of the balance of potential harms and benefits ofscreening.Hence they need to be informed and participate in decision making[69-73].It is considered an ethical duty to encourage people to decide for themselves[71].The 2017 Cochrane review on patient decision aids (an update of the most cited Cochrane review in 2014)[72]included studies involving adults making decisions for themselves,for a child or for a significant other,about screening or treatment options.None of the 105 included trials,and none of the excluded studies,addressed scoliosis.None of the discussed guidelines and position statements (Table 1 and Table 8) invited screeningparticipants or included an analysis of their voices.The SRS/AAOS/American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)/POSNA[33,46]or Scientific Society on Scoliosis Orthopaedic and Rehabilitation Treatment[35]statements do not contain any information on patients’ engagement or shared decision making.Five,out of ten,Wilson and Jungner[29]principles,considered by the SRS International Task Force[31,47],were technical efficacy,clinical effectiveness,program effectiveness,treatment effectiveness,and cost-effectiveness.The United Kingdom National Security Council formulated their recommendations based on eleven criteria[43],and the USPSTF on eight “key questions”[26](Table 8),none of them include such issues.

Table6 Fifty years after Wilson and Jungner,Consolidated principles for screening,2018[9]

Table7 “Drivers of overdiagnosis” and their relation to scoliosis screening

One present day phenomenon,of importance regarding sources of information and evidence,but also particularly about people-centredness,is the digital revolution.The access to health information has democratised,people are using new technologies to share information and experiences,build social networks and run blogs[70].Social networks are becoming sources of scientific evidence[83]and websites,blogs and social media are today recognised as grey literature[84].These apply for people with scoliosis,and for scoliosis research and practice[85-87].

The child perspective

The problem of screening for scoliosis is about adolescents and their school environment.In 2017,seven out of eight international screening programmes were school-based[26].

According to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child,children have,among other rights,the right to“express an opinion,and to have that opinion taken into account,to privacy,to protection from abuse or neglect”[65].In concert with this,the recent “Unique Needs of the Adolescents” Policy Statement of the AAP,calls for protecting the rights of adolescents through developmentally appropriate,adolescent-centred,family-involved care,addressing physical and mental health,confidentiality,socioeconomic factors,and sexual and gender development,in terms of identity,relationships and roles[64].(“In adolescents to whom confidentiality is not assured,there is a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms,suicidal thoughts,and suicide attempts”[64]).

The AAP’s Bright Future guidelines for health supervision were updated in 2017 and 2019 with a “new focus on social determinants of health and on lifelong physical and mental health”[36].Nonetheless,as of scoliosis,the guidelines simply refer to the 2015 position of the orthopaedic societies[46].

Table8 Unmet and partially met United States Preventive Services Task Force[26] and United Kingdom National Screening Committee[43] key questions and criteria,tested in recommendation formulation on screening for scoliosis

Evidence base and standards of recommendation formulation

The SRS/AAOS/AAP/POSNA in their 2015 statement[33,46]urged the USPSTF to update their recommendations in view of new evidence of brace treatment effectiveness[82].The conclusions of the USPSTF are,in fact,opposite.They formulated their “I” statement that “(…) the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of the service.Evidence is lacking,of poor quality,or conflicting,and the balance of benefits and harms cannot be determined”[34,74,75](Table 1).USPSTF follows rigorous guideline development standards and procedures[74,75].In contrast,their previous (2004) recommendation was based on a “brief evidence update”[88]of low methodological quality,lacking expected reporting of the search,selection,and appraisal of the evidence[25].

Importantly,both the USPSTF[26],and the United Kingdom National Security Council[43]systematic reviews,produced in the preparation of recommendation formulation (Table 1),did not find convincing evidence for a number of criteria and key questions,including harms of screening,long term treatment effects,and differences in health outcomes between screen- and clinically detected cases,as well as whether they may be associated with the condition,the treatment (including screening and workup) or the diagnosis (Table 8).

Expert opinions are contemporarily not considered as a substitute for evidence in guideline development standards and methods[10,11,27].Systematically developed guidelines – both current and historical (Table 1) – are,to a different extent,sceptical about school screening for scoliosis[24,25,32,34].Nonetheless,the distrust[41]and opposite claims[40,89,90]continue.

Continuum of disease definition – mild scoliosis

The minimum criterion for diagnosis of scoliosis,the cut-off point of 10° in the Cobb classification[26,91,92],is questioned[26,43]as “based on convention”[26].Brace treatment starts from 20-25° Cobb[35,53,91,92],so there is a gap between a diagnosed condition and a condition with available (effective) treatment[26,43]– one of the principles of a justified screening programme[1,8,9,28,29](Tables 4-6).Additionally,for the majority of screenpositive persons,adolescent idiopathic scoliosis will be a benign condition – curves progress among about two-thirds of adolescents,but only one-third and less than 10%of the diagnosed will experience progression of more than 10° and 30°,respectively[26,53].In the screening programmes,the majority of detected curves were 10°-19°,thus only the minority will progress to the 20°-25° threshold for brace treatment[26,93,94].And only very few will progress to more severe deformities,which may require surgery (prevalence of 0.1% in adolescents and of 0.4% in general population for curves exceeding 40°)[95].Furthermore,the false-positive rates for the routinely used,and recommended,forward bend test,are up to 21.5%[26].The critiques of population-based screening argue that deformities requiring treatment will be diagnosed clinically,even in the absence of screening programmes (Table 1).“Distribution of curves was similar for children detected through school-based screening compared to those who were detected clinically”[26].And the effectiveness of school screening on curve magnitude at clinical presentation,in comparison to clinically detected cases,is reported as doubtful[39].

Aesthetics and body acceptance are potential challenges in people with scoliosis:Labelling mild “deviations” from “norms” need to be considered in this context[96-98].The connection with scoliosis,body image and mental health issues are well recognised in research,but in people with diagnosed,typically serious,deformities,and who are treated for scoliosis[81,91,99-101].Not in “otherwise asymptomatic” (i.ehealthy) young people referred to screening.“Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis is most often asymptomatic during adolescence,and is (..) not typically associated with clinical finding other than body asymmetry”[26].

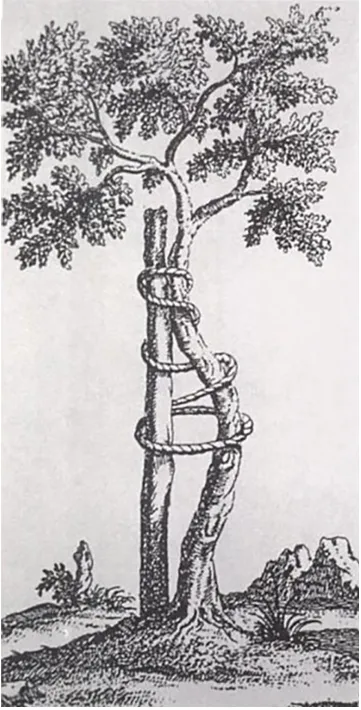

The evidence is unconvincing whether slowing down the curve progression has other positive health outcomes in body function and person-oriented outcomes such as pain,psychosocial status,and body experience.On the other hand,aesthetics is considered an important criterion of treatment[26].Mild scoliosis may be recognised as a health condition,as it is considered in both the prevailing societal stereotypes and biomedically (rather than psychosocially) oriented assumptions of straight (perfect)bodies[96,97,102-104](Figure 1).

The literal meaning of “orthopaedics” is “straight child,free from deformity”,and it comes from the XVIII century[105].

CONCLUSION

Opinion-based health care recommendations and guidelines tend to be no longer valid.Evidence-base,and strength of the recommendations,are followed,or at least addressed,in contemporary guidelines,recommendations and position statements on screening for scoliosis.Nonetheless,trustworthiness of individual documents remains disputable.Problems include formulating conclusions based on selective citations rather than on research syntheses,with emphasis on potential benefits of treatment,and silence on systematically developed recommendations against screening,or the fact that scoliosis screening has been discontinued in countries with established standards of guideline development and implementation.

Figure1 Tree of Andry.

Guidelines,recommendations and position statements are even more discrepant,when taking into consideration contemporary principles and standards of screening.These apply especially to experiences of people and potential personal harms,including those following over-detection and false-positive test findings,labelling,overtreatment,and stigmatisation.There is no consideration of the issues of informed choice and shared decision making.Knowledge translation tools,educational materials or patient decision aids are not considered in any of those documents.

Nonetheless,the discussed documents have at least one crucial commonality.The SRS/AAOS/POSNA/AAP 2015 position[33,46]includes a significant recommendation that “screening exams for spine deformity should be part of medical home preventive services”.The “Unique Needs of the Adolescents” statement promotes the Patient-Centred Medical Homes[64].Bright future guidelines recommend spine examination during individual Adolescent Periodic Health Visits[36].

Potentially,this could be a more respectful way of examining the spine than the school-based procedure.It does make a difference in terms of person-centredness,whole-person orientation and,more broadly,schools as “safe places”[64].Perhaps medical homes could be the right places to examine for scoliosis in adolescent- and family-oriented,respectful way,in confidentiality,by properly trained personnel,not only in terms of the accuracy of testing but also in terms of ensuring the unique needs of adolescents.As regards to screening programmes,potential harms to all screened adolescents,not only to those diagnosed,as well as shared decision-making,need to be considered.

Furthermore,all of these are recommendations for spine examinations rather than screening programmes.

It is important to stress that the idea of this paper is to highlight the issue of screening understood as a preventive programme,rather than as a test[1,8,9,29,30]or a clinical back inspection,especially in order to underline the important and underrepresented in the literature issues of people-centredness and shared decisionmaking.Standards such as the Bright Future guidelines[36],and reports on the necessity for accessible primary care for adolescents,including careful spine examinations[106],are unquestionable.

Nonetheless,there are still many debatable issues related to this subject matter,such as delivering services and ensuring person-centeredness in areas where health visits are not mandatory or not provided.One of the aims of this opinion review is an invitation for further discussion regarding this multidimensional subject matter.

In terms of preventive screening,an answer to the question on how to screen for scoliosis,instead of whether to screen (“to screen or not to screen for scoliosis”),is warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to deeply thank and,at the same time,dedicate this work to our Dear colleague and co-author,Professor Ejgil Jespersen,who sadly fell seriously ill.He has always been an advocate for the humanistic and personal way of treating every person,even when he or she happens to be in a role of a patient.We are grateful for his expertise,inspiration,and friendship.

World Journal of Orthopedics2020年9期

World Journal of Orthopedics2020年9期

- World Journal of Orthopedics的其它文章

- Supernumerary brachioradialis - Anatomical variation with magnetic resonance imaging findings:A case report

- Factors predisposing to thrombosis after major joint arthroplasty

- Effect of weekend admission on geriatric hip fractures

- Length unstable femoral fractures:A misnomer?