Effects of f luid balance on prognosis of acute respiratory distress syndrome patients secondary to sepsis

Yu-ming Wang, Yan-jun Zheng, Ying Chen, Yun-chuan Huang, Wei-wei Chen, Ran Ji, Li-li Xu, Zhi-tao Yang,

Hui-qiu Sheng1, Hong-ping Qu2, En-qiang Mao1, Er-zhen Chen1

1 Department of Emergency, Ruijin Hospital Aff iliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai,China

2 Department of Critical Care Medicine, Ruijin Hospital Aff iliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine,Shanghai, China

KEYWORDS: Sepsis; Acute respiratory distress syndrome; Fluid balance; Prognosis

INTRODUCTION

Sepsis is a severe critical care syndrome and a lifethreatening condition with high morbidity and poor prognosis.[1,2]Acute respiratory distress syndrome(ARDS) is a type of acute diffuse, inflammatory lung injury caused by various factors inside and outside the lungs, leading increased pulmonary vascular permeability, increased lung weight, and loss of aerated lung tissue.[3]Many studies have reported that sepsis is one of the most common and lethal causes of ARDS,[4]and nearly 40% ARDS incidence results from sepsis.[5-7]ARDS,as a main cause of acute respiratory failure, is mainly characterized by increased pulmonary endothelial and epithelial permeability, diffuse alveolar injury, and severe pulmonary inflammation.[8]Proteinaceous fluid accumulation in the pulmonary interstitial area or alveoli reduces pulmonary compliance and volume for patients with ARDS.[9]Therefore, f luid management is crucial to ARDS. However, choices of f luid resuscitation strategies and f luid input volumes remain a thorny problem. Several relevant studies[10-14]have been conducted to explore this problem but showed contradictory results. Fluid resuscitation is also the mainstay of therapy for sepsis.[15]Restricted fluid resuscitation and negative fluid balance are shown to be beneficial to the prognosis of sepsis patients.[16-18]However, for ARDS patients secondary to sepsis, only a few studies have been conducted to illuminate the relationship between fluid resuscitation and prognosis. The study aimed to explore this problem.

METHODS

We conducted a single-center and retrospective study in Ruijin Hospital (2,100 beds) Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine in Shanghai, China. It was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ruijin Hospital(Reference number: 2017119). Because our study was retrospective, the patient’s consent was not necessary.

Inclusion criteria

Patients were identif ied for the study if they met all of the following inclusion criteria: (1) age ≥18 years; (2)diagnosis of sepsis;[19](3) meeting the Berlin Definition for ARDS within 72 hours of sepsis onset;[20](4) duration of emergency intensive care unit (EICU) stay more than 72 hours.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded if they: (1) participated in other studies; (2) had inadequate medical records; (3)had concomitant pulmonary diseases; (4) died; (5) were discharged within 24 hours; or (6) needed emergency operations after EICU admission.

Data collection

Baseline data included demographics, sepsis category,source of sepsis, the origin of patients, comorbidities,Acute Physiologic and Chronic Health Evaluation II(APACHE II) scores, and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores during the f irst 24 hours after EICU admission. We also collected data of tidal volumes,PaO2/FiO2, positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP),duration of hospital and EICU stay as well as mechanical ventilation. The primary end point was in-hospital mortality, and the secondary end points were duration of hospital and EICU stay as well as mechanical ventilation.

Daily fluid input included oral, enteral, and intravenous fluids. Daily fluid output included urine volume, ultrafiltration, and fluid loss from drains and tubes. We didn’t consider insensible water loss. Daily net fluid balance for seven days was calculated by subtracting daily f luid output from daily f luid input.

We divided all patients into the ARDS group and the non-ARDS group. Furthermore, patients of the ARDS group were divided into survivors and non-survivors.

Statistical analysis

Continuous demographic and clinical variables were described as mean±standard deviation (SD) or median(interquartile range [IQR]), depending on the normality measured by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov method.Categorical variables were described as numbers and percentages. We used Student’st-test or Mann-WhitneyU-test to compare data of continuous variables, and Pearson’s Chi-square, continuity correction, Fisher’s exact, or likelihood ratio tests for categorical variables.Binary logistic regression analysis was applied to analyze the relationship between indicators with statistical signif icance (P<0.05) and mortality. If the twosidedP-value was <0.05, comparisons were considered signif icant. Analyses of data were performed using SPSS Version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

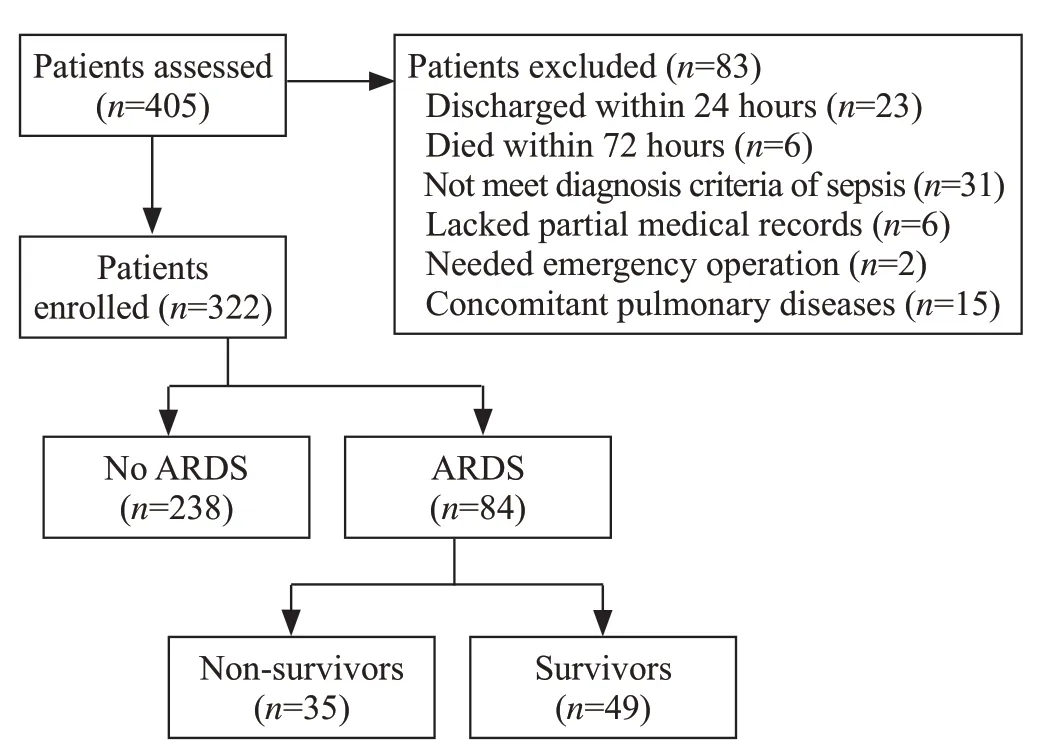

We assessed 405 patients in total, and 83 were excluded for various reasons which were listed in Figure 1. A total of 322 patients were enrolled finally, and 84(26.1%) had ARDS within 72 hours after sepsis onset.Among patients with ARDS secondary to sepsis, 49(58.3%) survived during the EICU stay (Figure 1).

First, we divided sepsis patients into the ARDS group and the non-ARDS group. Epidemiologic statistics compared between the two groups were counted as follows: men accounted for 60.6%, the median age was 62 (IQR 46-73) years, the mean body mass index (BMI)was 23.68±3.80 kg/m2, and patients with sepsis (59.6%)occupied a higher proportion (Table 1).

Most patients were from EICU (68.0%) and medical emergency ward (20.8%). The most frequent comorbidities were hypertension (42.9%) and diabetes(24.2%). Lung (56.2%) and abdomen (14.9%) were the most common sources of sepsis (Table 1).

Sepsis patients had a lower PaO2/FiO2ratio in the ARDS group than in the non-ARDS group (166.4±71.0 vs. 255.0±91.2,P<0.05). Besides, patients from the ARDS group had worse physical conditions, including higher illness severity scores and longer duration of mechanical ventilation (11 [6-24] days vs. 0 [0-0] days,P<0.05). Mortality rates were much higher in the ARDS group than in the non-ARDS group (41.7% vs. 15.5%,P<0.05). The duration of hospital and EICU stay didn’t show the statistical difference (Table 1).

Figure 1. Study f low chart.

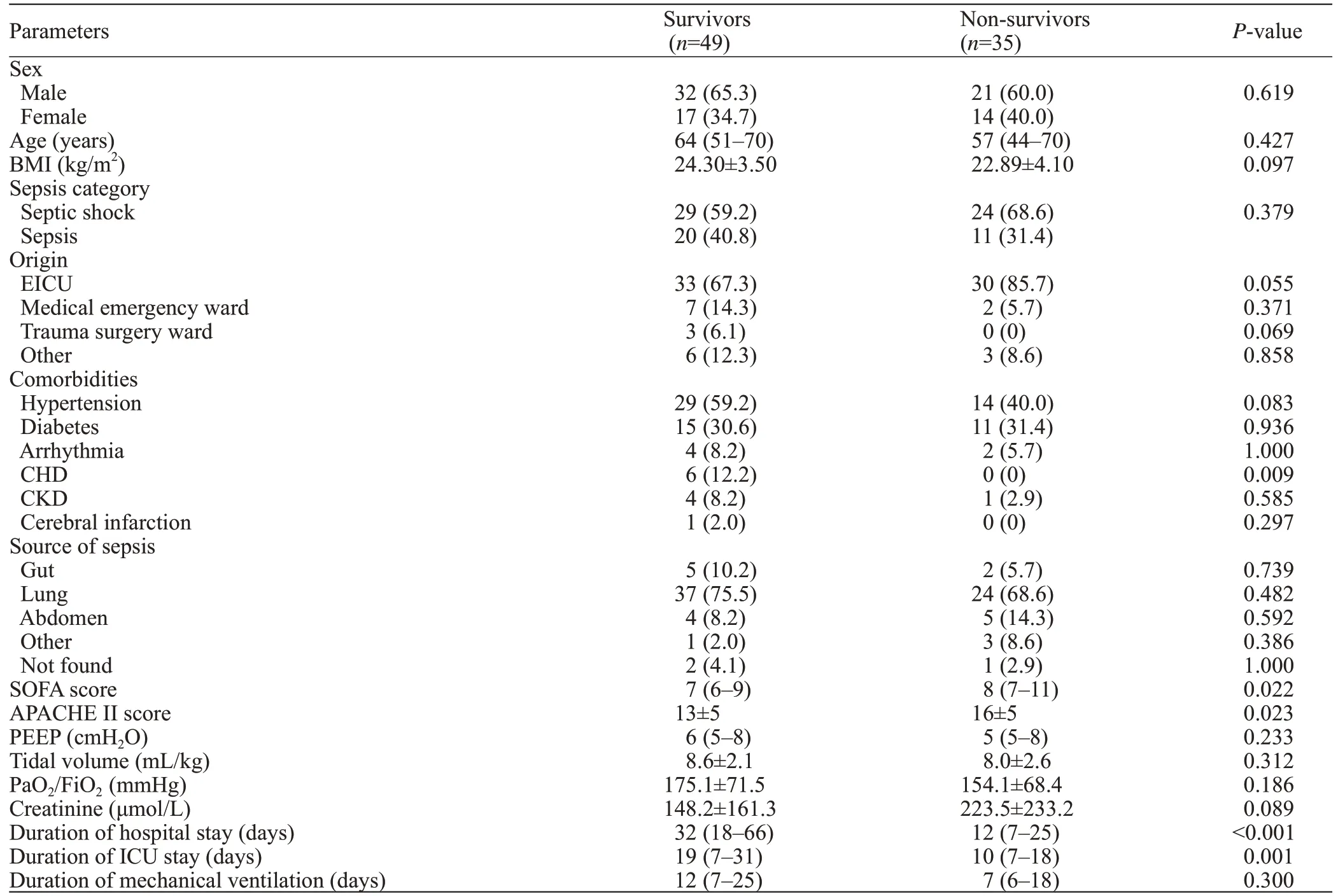

Non-survivors indeed had higher SOFA scores and APACHE II scores, as well as shorter duration of hospital and EICU stay than survivors. However, we didn’t find significant differences among tidal volumes, PaO2/FiO2ratio, and duration of mechanical ventilation between the two groups (Table 2).

In the f irst 24 hours, mean f luid input volumes in the ARDS group were more than those in the non-ARDS group (50.1±22.1 mL/kg vs. 41.0±21.6 mL/kg,P<0.05).During the 7-day period, patients with ARDS had more mean daily fluid input volumes (46.3±20.8 mL/kg vs.35.5±21.7 mL/kg,P<0.05) than those without ARDS,while mean daily output volumes between the two groups were similar (43.3±21.1 mL/kg vs. 40.7±21.3 mL/kg,P>0.05). Besides, we compared fluid input and output volumes between the two groups every day in seven days and found daily fluid input volumes were more in the ARDS group with signif icant differences while daily output volumes between the two groups didn’t show statistical differences except results on the 5thday.

Table 1. Characteristics of sepsis patients with or without ARDS

Patients with ARDS showed daily positive net fluid balance for seven days, while those without ARDS showed daily negative net fluid balance since the second day with statistically significant differences (P<0.05) (Figure 2).We compared net fluid balance every day for seven days between the ARDS group and the non-ARDS group and found all results had signif icant differences (P<0.05).

Figure 2. Mean fluid balance (mL/kg, mean±standard deviation) in sepsis patients with or without ARDS during seven continuous days after onset of sepsis. *Statistically signif icant difference at the P<0.05 level between two groups.

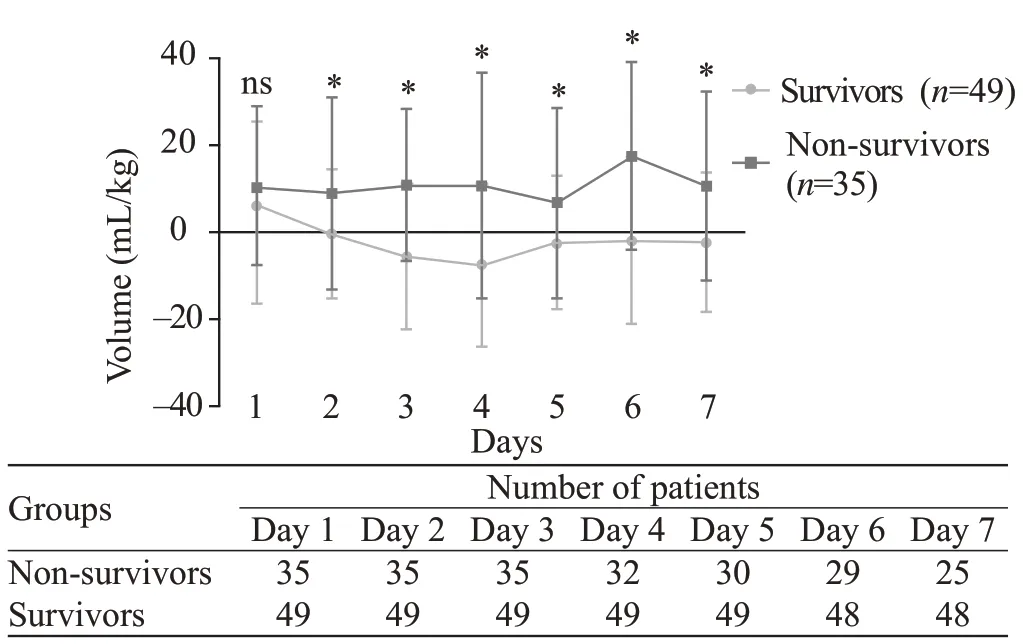

Figure 3. Mean fluid balance (mL/kg, mean±standard deviation) in survivors and non-survivors during seven continuous days in sepsis patients complicating with ARDS. *Statistically signif icant difference at the P<0.05 level between two groups. ns: not signif icant.

Table 2. Characteristics of survivors and non-survivors

Our results showed that mean daily fluid input volumes were much lower in survivors than in nonsurvivors (43.2±16.7 mL/kg vs. 51.0±25.2 mL/kg,P<0.01) while output volumes were much higher in survivors (45.2±19.8 mL/kg vs. 40.2±22.7 mL/kg,P<0.05). We also compared daily fluid input and output for seven days between the two groups. Results of f luid input showed statistical differences only on the 4thand 6thday, and f luid output consequences didn’t show statistical differences except for the 7thday.

Survivors showed daily negative net f luid balance for seven days except for the first day, while non-survivors showed daily positive net f luid balance every day during the 7-day period with statistically signif icant differences(P<0.01) (Figure 3). We compared net fluid balance every day for seven days between survivors and nonsurvivors and found all results except the first day had statistically signif icant differences (P<0.05).

Finally, we used binary logistic regression analysis to measure which of the following indicators, including SOFA score, APACHE II score, and mean daily fluid balance, were independent prognostic factors. Results demonstrated that only mean f luid balance (P<0.01) was independently associated with the prognosis of sepsis patients with ARDS.

DISCUSSION

ARDS is a clinical syndrome characterized by refractory hypoxemia with high mortalities. A study conducted in 15 adult ICUs of Shanghai between 2001 and 2002 reported that ARDS incidence accounted for approximated 2% of all ICU admissions with a 90-day mortality rate of more than 70%.[21]The main treatment method of ARDS was etiology treatment,and fluid resuscitation was considered as an effective supportive treatment method of ARDS patients for increased capillary permeability and protein-rich fluid accumulation as the most important pathophysiological changes.[8]Many studies reported the relationship between fluid resuscitation and prognosis of ARDS,but results were contradictory. A large randomized study conducted by Wiedemann et al[10]compared a conservative and a liberal strategy of fluid management in 1,000 patients with acute lung injury, and concluded that patients from conservative fluid administration group had a shorter duration of mechanical ventilation and ICU stay while there was no significant difference in the primary outcome of the 60-day mortality. Another post-hoc analysis of a cohort of 313 children with ARDS revealed that positive f luid balance (in increments of 10 mL/[kg·day]) was associated with a significant increase in both mortality and prolonged duration of mechanical ventilation, independent of the presence of multiple organ system failure and the extent of oxygenation.[12]Rosenberg et al[13]assessed the fluid balance of 844 patients from 24 hospitals and 75 intensive care units and found that negative cumulative f luid balance at day 4 of acute lung injury was associated with signif icantly lower mortality.However, some investigators[11]found f luid resuscitation strategy might be a potential risk factor for long-term cognitive impairment. Sepsis, as the most frequent cause of ARDS, has a close relation with ARDS in critically ill patients. In 2002, an epidemiological study reported that sepsis was the most common cause of acute respiratory failure.[22]Another study conducted by the Korean Study Group on Respiratory Failure declared the incidence rate of sepsis-induced ARDS was 6.8% in Korea.[23]Fluid resuscitation is a lifesaving therapy for both sepsis and ARDS patients but only a few studies have been conducted to explore the relationship between fluid balance and prognosis of ARDS secondary to sepsis. Murphy et al[24]carried out a study containing 212 patients with septic shock complicated with ALI and found both early fluid management and late fluid management of septic shock complicated with ALI can influence patient outcomes. However, the term“acute lung injury (ALI)” was eliminated by the Berlin definition of ARDS in 2012.[20]Our study used the newest criteria of ARDS and mainly focused on ARDS patients secondary to sepsis. We included 322 patients,and ARDS patients accounted for 26.1%. In the group of sepsis complicated with ARDS, survivors had much lower input volumes and higher output volumes than non-survivors. Survivors showed daily negative net fluid balance since the second day, while non-survivors showed daily positive net f luid balance every day during the 7-day period with statistically signif icant differences except the first day. These results indicated that sufficient volume was necessary to resuscitate patients during the early time and excess f luid infusion should be avoided for fear of aggravation of pulmonary edema or injury of other organs.Negative fluid balance since the second day might be a prognostic factor for ARDS patients secondary to sepsis.

Besides fluid resuscitation, lung-protective ventilation was also an important strategy for ARDS patients, which could reduce mortality. Several clinical trials have demonstrated that lung-protective ventilation with low airway pressure and tidal volumes could prolong the survival time of patients with ARDS.[25-27]For patients with ARDS, the use of lower tidal volumes during ventilation was also an effective treatment that could reduce the release of inflammatory cytokines and detrimental lung stretch.[28-30]An early clinical trial reported the lower tidal volume was approximately 8.1 mL/kg compared with traditional tidal volume,which was approximately 12.2 mL/kg.[31]We didn’t find significant differences in tidal volumes between survivors and non-survivors because we employed low tidal volumes as a routine treatment for all ARDS patients. As for PEEP, there was a lack of an accurate method to define it. Some investigators thought higher PEEP values might improve the prognosis of ARDS patients.[32]We compared PEEP values between survivors and non-survivors and found no statistical difference.Acute kidney injury (AKI) was also reported to be an independent prognostic factor of patients with sepsis.[33,34]We wanted to clarify whether the positive fluid balance was due to AKI. Results showed that there was no statistical difference in creatinine on sepsis patients with or without ARDS (178.8±198.7 μmol/L vs. 163.3±223.5 μmol/L,P>0.05). We also compared the creatinine level between survivors and non-survivors of sepsis combined with ARDS. Although the creatinine level was higher in non-survivors than in survivors (223.5±233.2 μmol/L vs.148.2±161.3 μmol/L), there was no statistical difference between the two groups (P>0.05). This indicated thatpositive fluid balance was not due to AKI and AKI was not an independent prognostic factor in our study.

Compared with sepsis patients without ARDS, the ARDS group did have higher SOFA and APACHE II scores, indicating a higher severity of the disease.However, we also knew that sepsis was a complex pathophysiological condition that might involve multiple organs. Due to the limited number of patients, we couldn’t make more detailed stratif ication to determine which factor had the most significant impact on prognosis. But our results showed that there was no difference in creatinine levels between the two groups, indicating AKI was not an important factor affecting the severity of the disease.However, the PaO2/FiO2ratio was signif icantly lower, and the duration of mechanical ventilation was significantly longer in sepsis patients with ARDS, suggesting that the severity of ARDS might be an important factor affecting the severity of the entire disease, but not the only factor.

There were some limitations in our study. This was a monocentric and retrospective study, and enrolled patients were not enough. Besides, clinical data during the first several hours were not recorded which might be more important. And some clinical and laboratory parameters we omitted could inf luence our results in some degree.

CONCLUSIONS

We conclude that early negative fluid balance since the second day is independently associated with a better prognosis of ARDS patients secondary to sepsis.Early enough f luid resuscitation and late restricted f luid resuscitation might be beneficial to the prognosis of ARDS patients secondary to sepsis.

Funding:This work was supported by Shanghai Shenkang Hospital Development Center of China (SHDC12017116);Program for Outstanding Medical Academic, Shanghai Municipal Committee of Science and Technology (184119500900);Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning(2016ZB0206, ZHYY-ZXYJHZX-1-201702) and Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (DLY201803) to Er-zhen Chen; Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning (201640089) to Zhi-tao Yang.

Ethical approval:The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ruijin Hospital (Reference number: 2017119).

Conf licts of interest:There are no competing interests involving this work.

Contributors:YMW wrote the f irst draft of this paper. All authors approved the f inal version.

World journal of emergency medicine2020年4期

World journal of emergency medicine2020年4期

- World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- Headache may not be linked with severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

- A primary pulmonary artery sarcoma associated with multiple lesions

- Andersen-Tawil syndrome associated with myopathy

- Severe bacteremia community-acquired methicillinresistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia in a young adult

- Stress-induced cardiomyopathy with electrocardiographic ST-segment elevation in a patient with pneumothorax

- Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and prosthetic heart valve: An additional coagulative challenge