Possible Use of Lumpfish to Control Caligus elongatus Infestation on Farmed Atlantic Salmon:A Mini Review

IMSLAND Albert K., REMEN Mette, BLOCH-HANSEN Karin, SAGERUP Kjetil, MATHISEN Remi, MYKLEBUST Elisabeth A., and REYNOLDS Patrick

Possible Use of Lumpfish to ControlInfestation on Farmed Atlantic Salmon:A Mini Review

IMSLAND Albert K.1), 2), *, REMEN Mette3), BLOCH-HANSEN Karin4), SAGERUP Kjetil4), MATHISEN Remi5), MYKLEBUST Elisabeth A.6), and REYNOLDS Patrick7)

1),4, 201,2),,, 5020,3),,9, 7010,4),, 9296,5),224, 8455,6),3, 9510,7),, 8140,

In this mini review, we systematized current knowledge about the number ofon farmed Atlantic salmon in relation to the use of lumpfish as cleaner fish. The review was prompted by reports of an unusually large number of sea lice () infestation of farmed salmon in northern Norway, Faroese Islands and Iceland and the urgent need to determine if common lumpfish can be used to reduce the number on farmed Atlantic salmon by actively grazing on sea lice. Available data from Norway clearly indicate that lumpfish grazes on, and it is possible to enhance this grazing with the assistances of live- feed conditioning prior to sea pen transfer and selective breeding. Observations from Iceland, Faroese Islands and Scotland also indicate that lumpfish can effectively lower infestations ofon salmon. Overall, this mini review expresses that lumpfish can actively lower the number ofon farmed Atlantic salmon.

sea lice;; lumpfish; salmon farming; welfare

1 Introduction

The sea lice,and variousspecies, are ectoparasites of marine finfish (Copepoda: Caligidae). They have a major impact on salmonid aquaculture worldwide (Igboeli., 2012, 2014); they cause a loss of over €440 million in Norway annually (Abolofia., 2017). The lice live on the mucus and skin and in the blood of fish, resulting in wounds if not removed. The lice occur naturally on salmon in sea water and were described as early as in the middle of the 18th century (Torrissen., 2013). However, the problem has escalated with the commercial production of Atlantic salmon (L) and rainbow trout (Walbaum) in sea cages. The effectiveness of medicinal treatments by either bathing or oral administration may be affected by the development of reduced sensitivity, leading to reducing treatment efficacy. Therefore, more emphasis has being giving to mechanical treatments such as thermolicing and high pressure washing. Biological con-trol using cleaner fish that pick the sea lice from salmonids is effective in reducing lice density and is adopted widely by salmon farming industry. As an alternative of cold- water cleaner fish, the common lumpfish,L., is currently used to control sea lice infestation (Ims- land., 2014a, b, c, 2015a, b).

The parasitic copepod family Caligidae comprises more than 30 genera (Kabata, 1979; Hemmingsen., 2020) and more than 450 species (Dojiri and Ho, 2013). Mem- bers of two of these genera,and, have received notoriety; they have the greatest economic impact among parasite genera in salmonid fish maricul- ture (Costello, 2006) and have evolved collectively as so called‘sea lice’. Although this notoriety is mainly due to the serious impact of, the members of genusare also implicated. Johnson. (2004) estimated that 61% of copepod infestations in marine and brackish water fish culture are caused by the members of family Caligidae, 40% by the species ofand 14% by the species ofA major difference be- tweenandsp. is their host specificity.is an obligate parasite of salmonid fish (Ka- bata, 1979) whereas manysp. tend to be facultative (Kabata, 1979; Pike and Wadsworth, 1999) and have been found on >80 fish species (Kabata, 1979). In the central and northern parts of Norway, a highNordmann abundance on farmed fish frequently occurs in autumn (Øines., 2006). Infections have been assum- ed to connect to passing schools of pollockL.), saithe (L.) and herring (L.) (á Norði., 2015).

Matureis smaller than mature(Piasecki, 1996), and its two sexes are at an equal size(around 6mm).is a much better swimmer thanand can re-infect other fish species if being removed from its original host (Øines., 2006; Hemmingsen., 2020). Hence, determining if matureinfects species like lumpfish and saithe should help to explain the rapid increase ofin sea pens during certain periods of year (Heuch., 2007) in northern Norway. Lumpfish are now extensively used as cleaner fish in northern Norway (Imsland., 2018), Ireland (Bolton-Warberg, 2018), Scotland (Treasurer., 2018), Iceland (Steinarson and Árnason, 2018) and the Faroese Island (Eliasen., 2018). However, to this date, there exists no systematic knowledge and guiding line of the effect of lumpfish onEarlier researches have clearly indicated that lumpfish prefer to graze the adult female(Imsland., 2014a, c, 2016, 2018). However, lumpfish in sea pens can be classified as the strongly opportunistic (Imsland., 2014c) and they do not restrict themselves to graze a single food source if others exist. They may readily graze on mature sea lice males as well as

In this mini review, we summarized the findings from both small and large scale trials with lumpfish where grazing onhas been reported in order to give recommendations on the possible use of lumpfish to com- baton Atlantic salmon in sea pens.

2 Different Densities of Lumpfish: Effect on the Occurrence of C. elongatus on Atlantic Salmon in Small Scale Studies

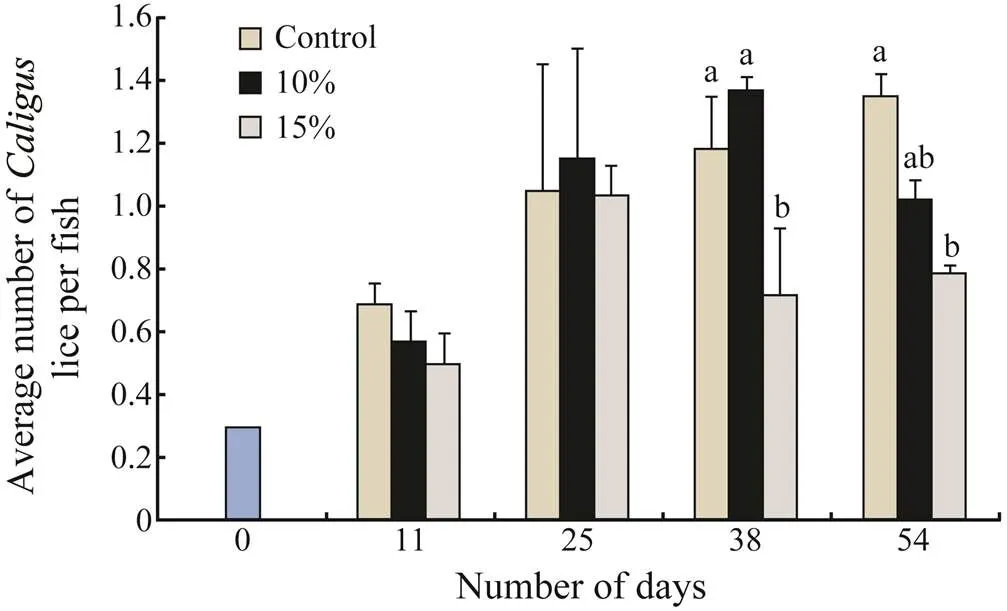

Imsland. (2014a) investigated the efficacy of lump- fish grazing on attachedon Atlantic salmon at two different lumpfish densities, 10% and 15%.were counted every two weeks during the trial (54 days). To investigate the stomach content of lumpfish, a gastric lavage was performed. The results showed that on day 38, 15% stocked cages had a significantly lower average number (0.72) ofper salmon compared to that of control (1.18) and 10% stocked cages (1.37)(Tukey’s multiple test,<0.05, Fig.1). Similarly, on day 54, 15% stocked cages had a significantly lower average number per fish (0.78) compared to that of control cages (1.35) and 10% stocked cages (1.02) (Tukey’s multiple test,<0.05).

Both visual inspection and gastric lavage indicated the consumption ofin the trialof Imsland. (2014a). The average number per fish varied throughout the trial although both 10% and 15% stocked cages had 25% and 42% fewerlice than controls on day 54. This finding strongly indicated that the presence of lumpfish has lowered the infestations ofamong Atlantic salmon. The results from the gastric lavage used to assess food choices in lumpfish displayed the presence ofin the stomachs of several fish throughout the study. The proportion of lumpfish with sea lice (and) increased from10% on day 11 to 28% on day 54. The number of lumpfish eating lice may in fact be much higher as these values were only determined from lavage fish every 14 days throughout the trial. The number of days between sample points allowed for lumpfish to consume sea lice and fully digest them, thus only giving a snapshot on lice eating. However, the relatively large increase in numbers of lumpfish found with ingested sea lice in their stomachs suggest that the level of grazing intensified throughout the study period. This may be an indicator of some forms of learning or habituation of lumpfish, which was investigated in a follow-up trial (see below).

Fig.1 Total average number of C. elongatus per fish recorded for each duplicate treatment during each of the sampling dates in the trial of Imsland et al. (2014a). Values are presented as means±S.D. Mean values which do not share a letter are significantly different (ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple range test, P<0.05). The average number refers to the total number of fish individuals sampled from two cages at each sampling time.

3 Habituation of Lumpfish by Feeding Live Feeds Prior to Transfer to Atlan- tic Salmon Net Pens: Effect on the Occurrence of C. elongatus

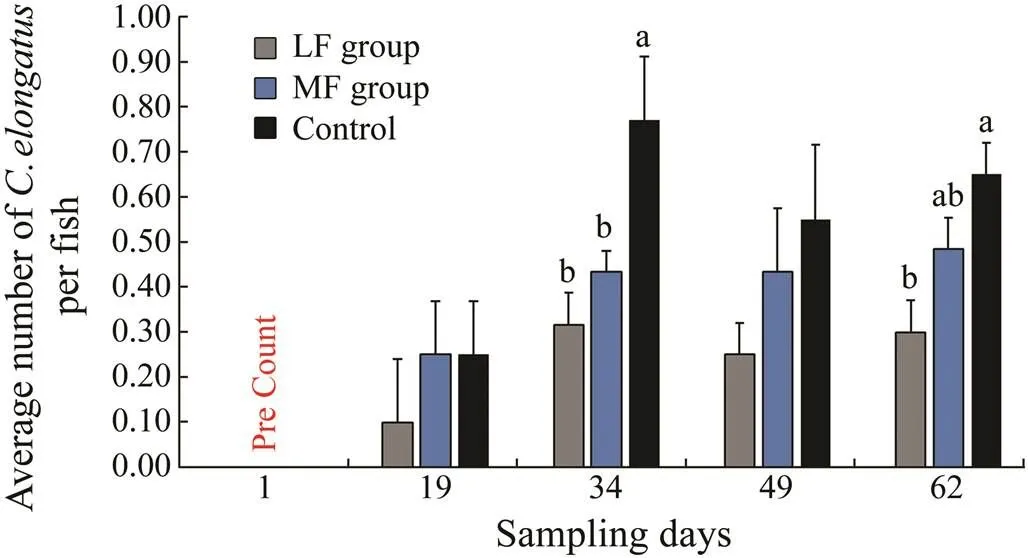

Imsland. (2019) established two groups of individually tagged lumpfish in land-based tanks. One group received marine pelleted feed (MF group) whilst the other received a mix of pelleted feed, live adult Artemia and frozen sea lice (LF group). Sixty lumpfish each group were tagged and transferred to small scale sea pens with 300 Atlantic salmon each, and the occurrence ofon the salmon was investigated for 62 days. They found that there were significantly lessstage on salmon from both LF and MF groups on day 34 compared to the control (SNK post hoc test,<0.05, Fig.2). On day 62, there was significantly lessfound on salmon from LF group compared to the control (SNK post hoc test,<0.05) as there was 38% lessfound on salmon reared with LF lumpfish compared to MF lumpfish.

Fig.2 Total average number of C. elongatus per Atlantic salmon recorded for each duplicate treatment during each of the sampling dates of the sea pen study carried out by Imsland et al. (2019). Values are presented as means±S.D. Mean values which do not share a letter are significantly different (ANOVA, SNK post hoc test, P<0.05). The average number refers to the total number of fish individuals sampled from two cages (n=60) each group each sampling time.

In the study of Imsland. (2019), the level ofwas significantly different between control and LF groups, indicating that the dietary treatment influenced the ability of lumpfish to effectively forage onas lumpfish conditioned prior to sea pen rearing were nearly 40% more efficient in grazingcompared to controls. These results provided further supports to previous studies which reported that lumpfish do graze on(Imsland., 2014a).is not included in Norwegian legislation, and there is therefore no legal limit to the level of infestation ofat which a treatment should be initiated. However, the spe- cies has an economic impact in the production cycle of salmon (Boxaspen, 2006). There have been some concerns on using lumpfish as a cleaner fish; the fish is considered to be a preferred host of(Heuch., 2007; Mitamura., 2012), and lumpfish has the potential to act as a vector ofthat can infect salmon (Powell., 2017). These concerns can be reduced if lumpfish graze indiscriminately on both species of lice and domesticated lumpfish free ofwere introduced into sea cages.

4 Lumpfish Grazing on C. elongatus: Possible Parental Control

Possible heritable component ofgrazing was investigated in two recent trials. Imsland. (2016) investigated possible parental control in grazing ofinnine families of lumpfish distributed in dup- licates among nine small sea cages stocked with 400 Atlantic salmon each. During the trial (78d), gastric lavage was performed every two weeks to assess the feeding pre- ference of individual lumpfish. Althoughin- festation rate was found to be very low in the study (Fig.3), the percentage of lumpfish found to have consumedvaried significantly between families, indicating a possible parental control ofgrazing.

Fig.3 Mean percentage values of C. elongatus found in nine lumpfish families sampled at each sampling time point. Data are from Imsland et al. (2016).

In a study carried out by Imsland. (unpublished), 10 families of lumpfish, 480 individuals each, 46.5±4.3g in mean weight, were distributed into ten sea cages (5m×5m×5m) stocked with 400 Atlantic salmon each, 387.3±10.3g in mean weight. From each family, 20 lumpfish were stocked into one of 10 sea cages and 20 into another cage, thus establishing duplicate treatments each family, two fa- milies each cage. During the trial (73d), gastric lavage was performed every two weeks to assess the feeding pre- ference of lumpfish individuals.

Consumption ofvaried between families (Fig.4). Seven of the ten families were found to consumeon day 18. Percentage of lumpfish that had consumedvaried between 2% and 11% on day 18. On day 62, between 5% and 40% of lumpfish were found within their stomach. Families 5 and 6 (half-siblings, same father) had the highest consumption ofthroughout the study (Fig.4).

Fig.4 Percentage values of C. elongatus found in stomach of lumpfish of ten families sampled at each sampling time point. Values are presented as means±S.D. Data are from Imsland et al. (unpublished).

Given the difference in consumption ofin two family trials and other natural source (see Imsland., 2016 for details), it seems that some lumpfish may be more predisposed in actively seeking natural food sources, including thatshould have a genetic basis to underline such a behaviour. It is well known that behavioural traits respond to both natural and sexual selection. Fish from families 5 and 6 in the second trial where consumption ofwas much more pronounced shared the same father but had different mothers. Given that these differences had a degree of genetic influence, then it would appear more likely that this difference was passed through paternal rather than maternal lines. Recent studies have revealed both maternal (Royle., 2012) and paternal (McGhee and Bell, 2014) effects on offspring behaviourepigenetic alterations of genome.

Results from two family trials indicated that consumption ofvaries among families. The families with the highest consumption of(trial 1, fa- mily 2; trial 2, families 5 and 6) were also those with the highest consumption of. Although energy rich salmon pellets were available, family 2 in trial 1 and fami- lies 5 and 6 in trial 2 preferred natural pray to a larger ex- tent than other families did. This confirmed that the gene- tic influence of sea lice consumption can be strong (Imsland., 2016). Given the difference in the consumption of naturalamong families, we may spe- culate that these fish are more disposed to seek out natural food sources. If this behaviour has a genetic basis, it may be further enhanced through selection and targeted breeding.

5 The Effect of Lumpfish on C. elongatus Incidence on Atlantic Salmon: Large-Scale Observations

5.1 Large-Scale Trial at Lerøy Aurora, Troms, Norway

Imsland. (2018) performed a large-scale trial at a commercial Atlantic salmon sea farm (69.80˚N, 19.41˚E) (Lerøy Aurora, Troms County, Norway) from October 6, 2015 to May 17, 2016. The experiment was conducted in eight large sea cages (130m in circumference, 37688m3in volume) holding 193304±2089 smolts (Atlantic salmon) each, initial mean body weight 198g±20g. Lumpfish were stocked at densities 4%, 6% and 8%, respectively, in duplicate sea cages. During the trial,on 240 sal- mon were counted every two weeks.

The level ofrose in all groups in autumn (Fig.5). Significantly, a lower level ofwas seen in lumpfish groups from late February to early April (Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc test,<0.05, Fig.5). In April,level decreased in all experimental groups, and the final level in May was similar to the initial ones in October last year.

Fig.5 Occurrence of C. elongatus per salmon (n=60) each group each sampling point in large scale sea cages at Lerøy Aurora, northern Norway, with 0 (control), 4%, 6% and 8% of lumpfish recorded each duplicate treatment each sampling dates (bi-weekly).

5.2 Large-Scale Observations at Nordlaks,Nordland, Norway

A large-scale observation was performed at a commercial Atlantic salmon sea farm (68.40˚N, 15.11˚E) (Nordlaks, Nordland county, Norway) from July 1, 2017 to February 2, 2018. The observation was conducted in 12 large sea cages (160m in circumference, 35000m3in volume) holding smolts (Atlantic salmon). Two nearby locations, Finnkjerka and Mollgavlen, in the same seawater basin (10km between them) were monitored. At Finnkjerka, there were six sea pens holding 198250±3200 salmon smolts each, initial mean body weight, 75g±9g, in October, 2016. In July 2017, about 12000 lumpfish each pen, mean weight, 32g±3g, were released to all these sea pens. In the nearby location of Mollgavlen, there were six sea pens holding 164724±8632 salmon smolts each, initial mean body weight, 76g±12g in October, 2016. Every other week during observation, thirty salmon each sea pen were sedatedand weighted individually with lice on them recorded. Af- ter counting, the lice remaining in container if any were also recorded. Lice were registered in 4 categories: 1), adult female; 2), pre- adult; 3), Chalimus; 4).

Overall, lesswere found on the salmon in pens with lumpfish (Finnkjerka location) compared with those without lumpfish (Fig.6). This effect was most evi- dent in winter and spring and also in summer;increased at Mollgavlen (without lumpfish) from July whereas such increase was not seen at nearby Finnkjerka (with lumpfish in sea pens). Overall, there were more sea lice challenges at Mollgavlen, resulting in approximately 600g loss of final slaughtering weight of salmon.

Fig.6 Sea lice development at two production sites of Nord- laks in northern Norway 2017–2018. Arrows indicate me- chanical and chemotherapeutical delouse operations during the observation period.

The relatively high number ofobserved in two large-scale studies was the indicative of all production sites, as these lice are known to transfer easily between fish (Heuch., 2007). Despite the presence of lumpfish, there were a sufficiently high number of lice elsewhere at the site to allow continual re-colonization in the cages stocked with lumpfish. Nevertheless, the mean num- ber ofwas lower in groups with lumpfish at both salmon farms. The added positive effect of lumpfish at the Nordlaks production sites was around 600g gain of slaughter weight (3.82kg. 3.18kg) at the location with lumpfish and this is almost surely linked to less problems with sea lice (bothand) at this lo- cation.

6 Summary

6.1 Lumpfish Efficacy for C. elongatus Removal

To summarize the relationship between the use of lump- fish and the occurrence ofon Atlantic sal- mon, we have compiled current knowledge from the published literatures and reports and by interviewing fish health care persons in Atlantic salmon farming industry in Table 1. Available data clearly indicates that lumpfish grazes onand it is possible to enhance this grazing with the assistance of live-feed conditioning prior to sea-pen transfer and selective breeding. Grazing is observed in va- rious size classes (25g to 550g), at temperatures ranging from 4 to 13℃ and in all seasons. Majority of published data come from northern Norway. There are also indications from the Faroe Islands, Scotland and Iceland that lumpfish grazes on. In the Faroe Islands, an investigation into 5511 lumpfish stomach (Eliasen., 2018) showed thatwas found in 13.5% of 743 individuals, of them, around 80% had alsoin their stomach (Kirsten Eliasen, Fiskaaling, Faroe Islands, pers. comm.). The consensus in the salmon farming indus- try in Faroe Islands is that lumpfish is effective in reducing the number of, but the infestation pattern is different from that of. Lumpfish is not systematically used as a biological delouser for(Kirsten Eliasen, Fiskaaling, Faroe Islands, pers. comm.). In Scotland, thenumbercan be seasonally im-portant, but the efficacy of cleaner fish tocan be difficult to assess in summer ascontinue to re-infect from a range of wild fish species. Even after bath treatments, re-infestation ofcan be rapid (Jim Treasurer, FAI Aquaculture, Scotland, pers. comm.). In the Westfjords area of Iceland,infestations are presently considered a more severe problem than theand the number ofon salmon can be high (>10) in late autumn (October–November) (Eva D. Jóhannesdóttir, Arctic Sea Farm Ltd., pers. comm., Hjörtur Methúsalemsson, Arnarlax Ltd., pers. comm.). In this area, large scale trials have clearly shown that lumpfish is very effective in lowering the number of.

6.2 Lumpfish and C. elongatus: Survey from the Salmon Farming Industry

To investigate in more details the possible effect of lump- fish onon Atlantic salmon, we conducted a survey by interviewing fish health personnel and biological controllers working in salmon farming industry in Nor-way (=18), Faroe Islands (=5) and Iceland (=2) (https://www.fhf.no/prosjekter/prosjektbasen/901539/). In Norway, we interviewed persons working in companies in northern Norway (.., from Production Areas (PA) 9–13, see Fig.1 in Overton., 2018). The survey findings showed that almost all participants agreed that lumpfish grazes on(Fig.7A), but the extent of grazing is unclear. On the Faroes Islands, all participants agreed that lumpfish grazes to a large extent onwhereas in northern Norway the views can be divided into large extentand some extent (Fig.7A). The survey on whether the grazing of lumpfish leads to reduction ofon Atlantic salmon showed different views on the extent ofreduction on salmon (Fig.7B). The majority in all three countries think that the grazing reduceson salmon to a large or some extent. In all three countries, it was commented that the lumpfish influences the number ofif the number ofon salmon is moderate or low.

Table 1 A summary of the current literature (peer-reviewed journal articles and scientific reports) and observations (including pers. comm.) on experiments with lumpfish and its effect on C. elongatus infestations on farmed Atlantic salmon

Note: Data include experimental period and temperature, experimental unit, experimental site/country, stocking density of lumpfish, effect investigated and effect if any.

Fig.7 Results from interview survey of fish health care per-son and biological controllers working in the salmon farm- ing industry in Norway (n=18), Faroe Islands (n=4) and Iceland (n=2).

Acknowledgements

Financial support was given by the Norwegian Seafood Research Found (Nos. KEKS901539and 901652EFFEK TIV).

Abolofia, J., Asche, F., and Wilen, J. E., 2017. The cost of lice: Quantifying the impacts of parasitic sea lice on farmed sal- mon., 32:329-349.

á Norði, G., Simonsen, K., Danielsen, E., Eliasen, K., Mols-Mor- tensen, A., Christiansen, D. H., Steingrund, P., Galbraith, M., and Patursson, Ø., 2015. Abundance and distribution of plank- tonicandin a fish farming region in the Faroe Islands., 7: 15-27.

Bolton-Warberg, M., 2018. An overview of cleaner fish use in Ireland.,41:935-939.

Boxaspen, K., 2006. A review of the biology and genetics of sea lice.,63:1304-1316.

Costello, M. J., 2006. Ecology of sea lice parasitic on farmed and wild fish.,22:475-483.

Costello, M. J., 2009. The global economic cost of sea lice to the salmonid farming industry., 32: 115-118.

Denholm, I., Devine, G. J., Horsberg, T. E., Sevatdal, S., Fallang, A., Nolan, D. V., and Powell, R., 2002. Analysis and management of resistance to chemotherapeutants in salmon lice(Krøyer) (Copepoda: Caligidae)., 58: 528-536.

Dojiri, M., and Ho, J. S., 2013.. Brill Publishers, Netherlands, 448pp.

Eliasen, K., Danielsen, E., Johannesen, Á., Joensen, L. L., and Patursson, E. J., 2018. The cleaning efficacy of lumpfish (L.) in Faroese salmon (L.) farm- ing pens in relation to lumpfish size and season., 488: 61-65.

Hemmingsen, W., Sagerup, K., Remen, M., Bloch-Hansen, K., and Imsland, A. K. D., 2020.and other sea lice of the genusas parasites of farmed salmonids: A review.,522: 735160.

Heuch, P. A., Oines, O., Knutsen, J. A., and Schram, T. A., 2007.Infection of wild fishes by the parasitic copepodon the south east coast of Norway.,77:149-158.

Igboeli, O. O., Fast, M. D., Heumann, J., and Burka, J. F., 2012.Role of P-glycoprotein in emamectin benzoate (SLICE (R)) re-sistance in sea lice,.,344:40-47.

Igboeli, O. O., Burka, J. F., and Fast, M. D., 2014.: A persisting challenge for salmon aquaculture.,4:22-32.

Imsland, A. K., Reynolds, P., Eliassen, G., Hangstad, T. A., Foss, A., Vikingstad, E., and Elvegård, T. A., 2014a. The use of lump-fish (L.) to control sea lice (Krøyer) infestations in intensively farmed Atlantic salmon (L.)., 424-425: 18- 23.

Imsland, A. K., Reynolds, P., Eliassen, G., Hangstad, T. A., Foss, A., Vikingstad, E., and Elvegård, T. A., 2014b. Notes on the behaviour of lumfish with and without Atlantic salmon present.,32: 117-122.

Imsland, A. K., Reynolds, P., Eliassen, G., Hangstad, T. A., Nytrø, A. V., Foss, A., Vikingstad, E., and Elvegård, T. A., 2014c. Assessment of growth and sea lice infection levels in Atlantic salmon stocked in small-scale cages with lumpfish.,433: 137-142.

Imsland, A. K., Reynolds, P., Eliassen, G., Hangstad, T. A., Nytrø, A. V., Foss, A., Vikingstad, E., and Elvegård, T. A., 2015a. Feeding preferences of lumpfish (L.) main- tained in open net-pens with Atlantic salmon (L.).,436: 47-51.

Imsland, A. K., Reynolds, P., Eliassen, G., Hangstad, T. A., Nytrø, A. V., Foss, A., Vikingstad, E., and Elvegård, T. A., 2015b. Assessment of suitable substrates for lumpfish in sea pens., 23: 639-645.

Imsland, A. K., Reynolds, P., Eliassen, G., Mortensen, A., Hansen, Ø. J., Puvanendran, V., Hangstad, T. A., Jónsdóttir, Ó. D. B., Emaus, P. A., Elvegård, T. A., Lemmens, S. C. A., Ryd-land, R., Nytrø, A. V., and Jonassen, T. M., 2016. Is cleaningbehaviour in lumpfish (C) parentally con-trolled?,459:156-165.

Imsland, A. K., Hanssen, A., Reynolds, P., Nytrø, A. V., Jonassen, T. M., Hangstad, T. A., Elvegård, T. A., Urskog, T. C., and Mikalsen, B., 2018. It works! Lumpfish can significantly lower sea lice infections in large scale salmon farming.,7 (8):bio036301, DOI:10.1242/bio.036301.

Imsland, A. K. D.,Frogg, N. E., Stefansson, S. O., and Reynolds, P., 2019. Improving sea lice grazing of lumpfish (L.) by feeding live feeds prior to transfer to Atlantic salmon (L.) net-pens.,511:734224.

Johnson, S. C., Treasurer, J. W., Bravo, S., Nagasawa, K., and Kabata, Z., 2004. A review of the impact of parasitic copepods on marine aquaculture.,43:229-243.

Kabata, Z., 1979.. The Ray Society, London, 468pp.

McGhee, K. E., and Bell, A. M., 2014. Paternal care in a fish: Epigenetics and fitness enhancing effects on offspring anxiety., 281: 1146-1151.

Mitamura, H., Thorstad, E. B., Uglem, I., Bjorn, P. A., Okland,F., Naesje, T. F., Dempster, T., and Arai, N., 2012. Movements of lumpsucker females in a northern Norwegian fjord during the spawning season.,93:475-481.

Overton, K., Dempster, T., Oppedal, F., Kristiansen, T. S., and Gismervik, K., 2018. Salmon lice treatments and salmon mor- tality in Norwegian aquaculture: A review.,11: 1398-1417.

Piasecki, W., 1996. The developmental stages ofvon Nordmann, 1832 (Copepoda: Caligidae).,74:1459-1478.

Pike, A. W.,and Wadsworth, S. L., 1999. Sealice on salmonids: Their biology and control.,44:233-337.

Powell, A., Treasurer, J. W., Pooley, C. L., Keay, A. J., Lloyd,R., Imsland, A. K., and Garcia de Leaniz, C., 2018. Cleaner fish for sea-lice control in salmon farming: Challenges and op- portunities using lumpfish.,10:683-702.

Royle, N. J., Smiseth, P. T., Kolliker, M., Champagne, F. A., and Curley, J. M., 2012.Oxford University Press, Oxford, 304324.

In:. Treasurer, J. W., ed., 5M Publishing Ltd., Sheffield, 420- 435.

Torrissen, O., Jones, S., Asche, F., Guttormsen, A., Skilbrei, O. T., Nilsen, F., Horsberg, T. E., and Jackson, D., 2013. Salmon lice–Impact on wild salmonids and salmon aquaculture., 36: 171-194.

Treasurer, J. W., 2002. A review of potential pathogens of sea lice and the application of cleaner fish in biological control., 58: 546-558.

Treasurer, J., Prickett, R., Zietz, M., Hempleman, C., and Garcia de Leaniz, C., 2018. Cleaner fish rearing and deployment in the UK. In:. Treasurer, J. W., ed., 5M Publishing Ltd., Sheffield, 376- 391.

Øines, Ø., Simonsen, J., Knutsen, J., and Heuch, P., 2006. Host preference of adultNordmann in the laboratory and its implications for Atlantic cod aquaculture., 29: 167-174.

. E-mail: albert.imsland@akvaplan.niva.no

January 22, 2020;

March 16, 2020;

May 16, 2020

(Edited by Qiu Yantao)

Journal of Ocean University of China2020年5期

Journal of Ocean University of China2020年5期

- Journal of Ocean University of China的其它文章

- Phaeocystis globosa Bloom Monitoring: Based on P. globosa Induced Seawater Viscosity Modification Adjacent to a Nuclear Power Plant in Qinzhou Bay, China

- Effect of pH, Temperature, and CO2 Concentration on Growth and Lipid Accumulation of Nannochloropsis sp. MASCC 11

- Fuzzy Sliding Mode Active Disturbance Rejection Control of an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle-Manipulator System

- The 9–11 November 2013 Explosive Cyclone over the Japan Sea- Okhotsk Sea: Observations and WRF Modeling Analyses

- Real-Time Position and Attitude Estimation for Homing and Docking of an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Based on Bionic Polarized Optical Guidance

- Characterization of the Complete Mitochondrial Genome of Arius dispar (Siluriformes: Ariidae) and Phylogenetic Analysis Among Sea Catfishes