他和1000座浙江古桥相遇

俞跃

因為想要留住家族老屋的记忆,我选择了拍照的方式,因为顺便拍了老屋周边的风光,我迷上了拍摄乡村的古桥。

我叫裘洪春,一个喜欢拍摄古桥的人。从2012年起到现在,我的镜头已经与1000多座古桥相遇、相知。

迷上拍摄古桥,要从一幢老屋说起。那是我家祖上在浙江嵊州崇仁古镇上的一幢百年老屋,有青砖、黛瓦、马头墙。因为后来搬到杭州,老屋无人,日渐衰败,我担心它会倒下来,却又无计可施。2012年,我想到一个可以保存记忆的方式——拍照。

20世纪80年代,我曾学习过摄影和冲印,但后来中断若干年。这次因为要拍老屋,我重新拾起摄影,但最初也只是拿了一部傻瓜相机就回老家了。

拍完老屋,我顺便拍下了周边的风光和建筑,还有村里的古桥。

拍着拍着,我就被乡间的古桥吸引住了:这些普普通通的石桥虽已很少被用到,但还看得出巧妙的构造、质朴的外形,历经几百年风雨而不倒。

我想,如果没有及时记录下来,古桥是不是也会像老屋一样被人遗忘。我觉得自己可以做点事情——“拍桥之旅”随之开启。

从此,我利用双休日自驾到乡村,去找造型古朴的桥梁。每次拍到一座桥,我就会把它的年代、位置记录下来,然后再去找下一座。我发现,有的桥已被列为文保单位,有的则被岁月遗忘,散落在不知名的山间和溪流上。

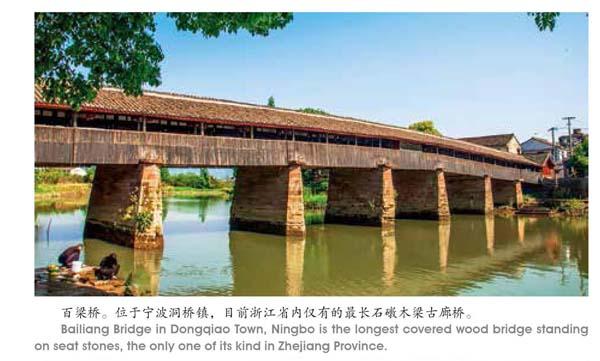

浙江山路多,水路也多,所以桥就多。只要花时间和精力去找,我想就能把它们一一记录下来。

家人也非常支持我的行动,2013年,我还特意买了单反相机尼康D90,去拍浙江的古桥。

要说拍桥,其实最辛苦的地方是难找。每次出发前,要大量翻阅地方志,再靠卫星地图,顺河流走向估测判断桥所在的位置。

实地找桥的过程,也很花时间、折磨人。有的桥因年代远,桥名被当地人改了又改,加上各地方言不同,实际发音与文字资料的描述偏差较大,有时难免要走冤枉路。在农村,许多古桥位置偏僻,遇到原路改道或封道,就不得不绕远路抵达。

其实,古桥并不好拍。尤其是小型石梁桥,造型越简单,要拍好就越难。为了拍桥额和拱券(又称券洞),有时需要趴在桥下或走到溪滩上,这就十分危险,有一次我差点连人带相机都滑进水里。

有时我也会觉得太累,想放弃。在外人看来,这更是一件费时、费力又非常孤独的事。因为我不是考古学家,找桥、拍桥也不会产生别的收入。但每次我回头看照片,想到这样做能让更多人了解古桥并去保护它们,我就觉得有意义。

在浙江境内,我最远到过泰顺,也是在那里拍到了被洪水冲垮的廊桥——文重桥。这座桥很幸运,听说当地找回了大部分原构件,而留在我照片里的是它被冲毁前的原貌。

这些年,我觉得光把古桥拍下来远远不够,要了解它们就要多看书。我最喜欢的书有两本,一本是梁思成的《中国建筑史》,另一本是茅以升的《中国古桥技术史》,后者讲了石拱桥的建造技法,尤其是讲了古桥构件。加上其他一些有关桥梁方面的书,帮我打开了视野,让我更期待亲眼看到古桥的精妙结构,而利用实地拍摄的机会,去对照、揣摩,感受更深。

浙江古桥梁造型独特,光石拱桥拱券的堆砌方法就有几十种。我越往后拍,越觉得单拍一座桥意义还不够,要将局部细节也拍下来,比如要将桥心石、桥额、望柱、雕刻以及抱鼓石的纹饰等一一记录下来。

至今,我跑过了浙江约65%的乡村,穿过了记不清的河道、溪流,一共拍下了1000多座浙江的桥。

我拍古桥,基本属于那种“记录式”拍摄,努力拍出古桥的气势、画面所蕴含的故事性。在拍摄过程中,我还会尽可能增加一些“可看性”。我希望看到的人能从这些“记录式”的照片中,体会到浙江古桥最原本的建筑之美。

希望我拍过的古桥,能被更多人了解、喜欢、重视和爱护。

One Photographer, 1,000 Ancient Bridges

By Yu Yue

My name is Qiu Hongchun. I am a photographer with a passion of photographing ancient bridges. Since 2012, I have photographed over 1,000 ancient bridges within Zhejiang.

Before my family and I moved to Hangzhou, we had a brick house in Chongren, our hometown in Shengzhou in eastern Zhejiang. Without anyone looking after it, the 100-year-old house was dilapidated and could come down at any time. In 2012, I thought of a way to preserve the house. I wanted to photograph it so that the house could stand forever in photos.

I learned the essentials of photography in the 1980s and but I didnt practice photographing for years and years. In order to eternalize the image of the home house, I took up my camera again. I went back and photographed the house with a point-and-shoot camera. After photographing the house, I was attracted by the sceneries of the ancient town. So I expanded my memorial trip into a field study of Chongren. Then I found I fell for the ancient bridges. Though these bridges were no longer in use, they looked fine, showcasing the artful craftsmanship of bridge builders in ancient times. These stone bridges had been around for several hundreds of years.

I found myself thinking about the destiny of these bridges. If they were left unattended, they would eventually vanish, just like the old family house in town. I thought I could photograph them. I therefore started a project to photograph ancient bridges across Zhejiang.

My trips always occur on weekends. The most challenging part of the work is the preparatory homework I need to do before I even drive my car to a destination. I first look into regional histories for information and then check rivers out on satellite maps to decide where these bridges are. Locating an ancient bridge isnt easy. As names change and dialects sound confusing when these names are spoken of by local residents. The real pronunciations of bridge names are often different from their names written in books. Occasionally, a trip can be a waste of time. Many of ancient bridges are in remote rural regions. Some roads are not in use any more. In some cases, I had to take a long detour to reach a remote bridge.

One year after I started photographing bridges, I bought a Nikon D90. My family backs me up to do this ambitious project.

Photographing a bridge isnt easy at all. A small stone bridge can give me a lot of trouble: it may look simple enough, but it isnt simple to figure out a way to take a good photo. It can even be dangerous in some cases. On a mission, I slipped and nearly fell into the river when I was trying to take a photo on the riverbank.

I have thought of giving up more than once. It takes time, money and dedication to travel and take so many photographs. I am no archaeologist. Seeking out a bridge and taking photos are not as rewarding as may be imagined. But I always feel invigorated when I look at the bridges in my photos. The world should have an opportunity to look at these bridges and do something to keep them alive and I am one of the photographers who are doing this opportunity job.

The farthest part of the province I have reached is Taishun, a county in southern Zhejiang. One of the corridor bridges I have photographed is Wenchong Bridge, a cultural relic under the protection of the national government. The bridge was totally damaged in a typhoon flood in September, 2016. The photo I took of the bridge provides an image that cant be seen in reality now. I hear most building blocks of the wood structure, first built in 1745 and rebuilt in 1857 and 1930 respectively, have been recovered. I sincerely hope it can be restored again.

Photographing a bridge takes time and knowledge. A bridge has many parts and details and there are many ways to photograph them all. In order to take meaningful photographs, I have read two books in recent years: by Liang Sicheng (1901-1972) and by Mao Yisheng (1896-1989). The books help me open my eyes to the beautiful nuances of the structures and building blocks of ancient bridges.

I photograph ancient bridges in Zhejiang in a documentary style. I want to showcase the vigor and story of these bridges. I want to make these bridges come to life in my photos. I want to make these bridges more presentable. I really hope that some viewers can appreciate the original architectural beauty of these bridges.

So far I have visited about 65% of the rural regions of Zhejiang Province. I dont remember exactly how many rivers and streams I have visited. The bridges I have photographed add up to more than 1,000.