Art Making as Analysis: Thought-Images and Image-Thinking

Mieke Bal

Abstract: On the basis of an experiment with and experience of making art as a mode of performing a cultural analysis of an object of cultural heritage —— Miguel de Cervantes’s world-wide known novel Don Quijote——in this article I explore the integration of what is now usually called “artistic research” with the historical genre of Denkbilder (Thought-Images). If done with precision and caution, this integration can yield a substantial innovation of the methodology of cultural analysis as well as of the practices of museum display, literary analysis, and audio-visual art-making. Most importantly, the project entails a revision of the much-abused concept of trauma, and suggestions for the way society can productively deal with traumatized people who seem “mad”.

Keywords: form; formlessness; museology; theatricality; trauma; image-thinking; thought-images

1. Sancho (Viviana Moin) holds Don Quijote (Mathieu Montanier) in order to comfort him at the end of the episode “Narrative Stuttering” (Photo: Mar Sez)

At the end of October 2019, the Småland Museum in Växjö, Sweden, opened an exhibition of my video workDonQuijote:SadCountenances. This project consists of sixteen channels and 33 photographs. It was conceived by French actor Mathieu Montanier, who plays the figure of Don Quijote and myself, in a gestation period during which we discussed the best way to do this project. Early on we decided that loyalty to Cervantes’s monumental novel with its eerily chaotic form, required that we abandon the idea of a linear film. Hence, the multiple-channel installation. It was accompanied by a book, with the same title, published by Trolltrumma, a small, very creative publishing company based in Växjö, which was created by Niklas Salmose, a professor of literature in English at Linnaeus University in Växjö. With true collegiality, this colleague has made the exhibition and the book possible, for which I am deeply grateful. The production of 25% of the videos, most of it shot by Jonas Valthersson, the installation in the museum, and the extended discussions at that university’s Centre for Intermedial and Multimodal Studies (IMS) are examples of what I discuss in this paper: the integration of art-making and academic analysis. Opening the exhibition was also an event of opening up the media-bound approach to art.①

Two weeks later, the “same” exhibition opened in the exhibition space of the Facultad de Bellas Artes of the University of Murcia in Southern Spain. Here, the possibility to exhibit was due to artist and vice-dean of the faculty, Jesús Segura, who has done 75% of the filming, in Murcia and in Paris. The aesthetic of each of these two presentations are so different that I put scare quotes around the word “same”. It so happened that the space in Småland was rather dark, with burgundy bricks on the walls, whereas the space in Murcia was shiny white. The difference makes my case, which I will propose below, that curating, as well as space itself, are integral parts of the artistic and intellectual event of an exhibition. What the two exhibitions have in common is the integration of benches for visitors to sit on, become part of the display, get close to the subjects in the scenes, and feel comfortable enough to determine themselves how long they want to stay with each episode.

I was the first to be surprised by the instant interest in this exhibition, in various places. Three more exhibitions are already planned, and it looks like more will follow. I find the relation to nation and national identity particularly heart-warming. That Swedish audiences were interested in this work based on a Spanish literary masterpiece from long ago, is amazing in itself. It is telling evidence of a non-nationalistic cultural attitude, an opening up towards the rest of Europe, and the world. That Spanish people are interested, instead of feeling that, as a Dutch person, and with a French actor playing the main character, I have abducted or appropriated their cultural heritage, is amazing for seemingly opposite reasons. Yet, this, too is proof of a cultural attitude of openness, not-confined by nationalism.②

2. Installation in Växjö. Photo: Ebba Sund.

3. Installation in Murcia. Photo: Luz Baón.

For now, instead of introducing the project in detail, it seems more appropriate to the subject of this article on practice, to open my argument jumping into the middle of that practice. In line with the aesthetic of the project, I begin “in medias res”, a narrative and intellectual device, or strategy, that also makes particular sense, leading to “immersion”.③The scene titled “Narrative Stuttering” shows Don Quijote as incapable of telling his story. He is alone on a dark theatrical stage. Sancho Panza is sitting on a chair on the side, helping him when needed, as a prompter. The knight is trying desperately to tell his story, the adventures, his opinions, whatever happened to him, but he is unable to act effectively as a narrator. The darkness of the stage deprives the space of perspectival depth, at times making Don Quijote almost seem floating. At the end, he bursts into tears, and Sancho holds him in order to comfort him, demonstrating, by physical touch, that he is not entirely alone (photo 1). This episode, and its ending, proclaim the “point” of this work: to solicit empathy.

Theatricality: The Point of Revising Museology

The stage isolates Don Quijote, and, at the same time, gives him an audience. The theatrical setting is a material “theoretical fiction” that explores how theatricality can perhaps help to enable the narratively disabled. But what is theatricality? Theatre scholar Kati Röttger considers theatricality a specific mode of perception, a central figure of representation, and an analytic model of crises of representation that can be traced back to changes in the material basis of linguistic behaviour, cultures of perception, and modes of thinking.④The multi-tentacled description gives theatricality many functions, and foregrounds its inherent intermediality. In addition, and more specifically for our project, theatre and performance scholar Maaike Bleeker gives theatricality the critical edge that the exhibition seeks to achieve when she calls it “a critical vision machine” (259).⑤

For this need of the narratively incapacitated figure in his theatrical setting, and the likes of him in real life, an empathic audience is indispensable. For this reason, there is an audience in the theatre, whose near-silent presence is sometimes audible. It is the task of the artwork to solicit such an audience. This is a primary goal of the exhibition. For this to be possible, a form of display is required that changes from the traditional museal display, which keeps audience members at a distance —— a distance often materialized by bars, cords, signs, and enforced by guards. Moreover, such routine display is testing on the audience’s physical condition, since standing and walking are the habitual modes of visiting. This governs the temporality of looking. In the theatre, by contrast, visitors can sit, and if the display is nearby and accessible, and visiting can consist of quietly sitting, the museum becomes a kind of theatre in this sense. This exhibition as a whole seeks to produce such material comfort facilitating affective attachment in visitors. The consequence is a radically different temporality of viewing. And time, thus, turns out to be a factor of affect.

This imagining, testing, and reasoning is one example of how this project pertains to what is most frequently called “artistic research” —— a search through analysis through artmaking. The concept is not unproblematic, but the undertaking is worthwhile. In such an endeavour, the search is not for direct academic answers. It is an attempt to make “thought-images” (from the GermanDenkbilder) by means of its counterpart, the activity of “image-thinking” that help understanding on an integrated level of affect, cognition, and sociality. I have called the specific genre of video production that seeks to create thought-images in previous works, “theoretical fictions”; and this is the genre here as well. This is the deployment of fiction to understand and open up difficult theoretical issues, and to develop theory through imaging what fiction enables us to imagine. Here, the issue that was “too difficult” for academic argumentation only, is the attempt to make museums more hospitable. Theoretical fiction can also be seen in the work of artists. This is how Leonardo da Vinci, for example, solved his problem of making his complex, abstract knowledge concrete and thus, clearer for himself, and understandable through visualization in painting.⑥

How to Visualize a Novel?

The challenge to make a video project based onDonQuijoteis quite specific in its troubled relationship between content and form, and between the narrative and visual aspects involved. The “research” part, based on a literary-cultural analysis of the novel, was, firstly, to decide which aspects of the novel are crucial to make a work that has a “point”. Secondly, that point had to make connections between artistic and social issues, and to improve our understanding how these two domains can go together, in the present, with the collaboration of the past in what we call “cultural heritage” —— here, Cervantes’s novel. This term, again, is somewhat problematic, since it suggests the passive reception of a gift. But the importance of the past for the present must be foregrounded. And finally, of course, the selected aspects and fragments had to be “audio-visualisable”, to be able to liberate them from confinement in the linguistic domain that requires reading, to foreground the imagination in “imaging” them, and open them up for collective perception, interpretation and discussion.⑦

On my reading, the predominant issue that rules the novel’s aesthetic is the difficulty of story-telling due to the horror encountered. The horror, in this case, is the five-and-a-half years of slavery Cervantes experienced as a young soldier, captured and sold by corsairs. The episode told by an unnamed escaped “Captive” in the chapters 39 to 41 of the novel’s first part is so ostensibly autobiographical, apart from its fairy-tale ending, that it becomes inevitable to see a traumatic aesthetic in the incongruous, wild story-telling. The project, therefore, appealed to two ambitions. First, the current situation of the world makes a deeper, more creative, and “contagious” reflection on trauma and its assault on human subjectivity, an urgent task for art. The insights the novel harbours uniquely connect to other experiences of war, violence, and captivity. Second, a well-thought-through video project can explore and transgress the limits of what can be seen, shown, narrated, and witnessed, specifically (but not exclusively) in relation to trauma, which is itself notoriously un-representable.⑧

In particular, the research of which this project is the result in substance and form, concerns more than the content, relevant as it is. The mode of story-telling is the primary target of the search. There is something enigmatic about the world-wide fame of a novel that, when read, seems in all kinds of ways unreadable. Full of incongruous events and repetitive stories, maddening implausibility, lengthy interruptions of the story-line, inserted poems and novellas, and at the same time, anchored in a harrowing reality, while also making readers laugh out loud, it challenges reading itself. I wonder every time I reread it, or sections of it, what the appeal is that keeps me haunted. Yet, the many feature films based on this novel mostly bore me —— in spite of all due respect for the great makers who tried, from Orson Welles who could not finish it to Terry Gilliam who took fifteen years to do so. This paradox triggered the underlying “artistic research” or “image-thinking” question.⑨

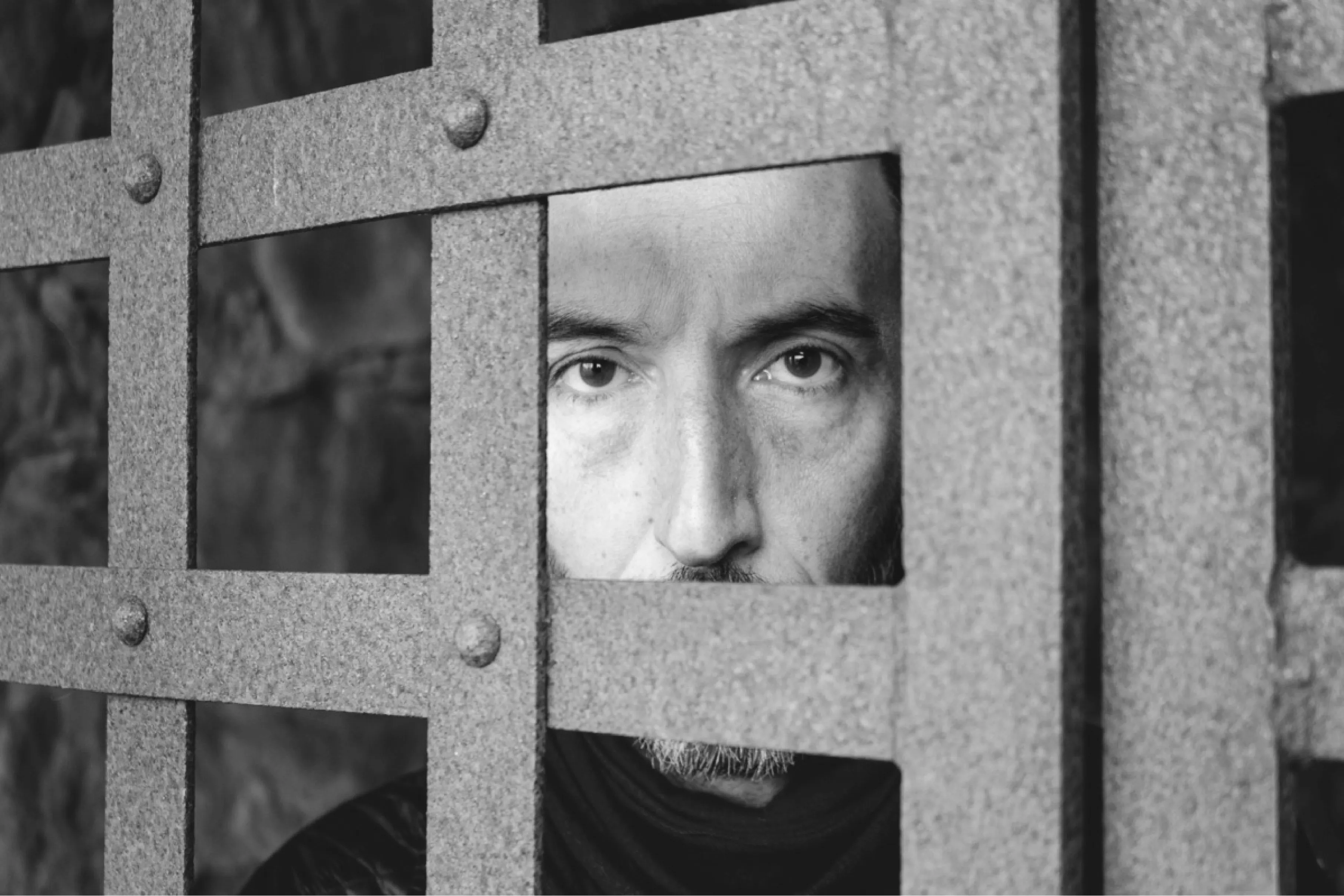

4. Mathieu Montanier as the Captive behind bars. Photo: Ebba Sund

The two-dimensional medium of photography, if well thought-through as a form of image-thinking, can do more to convey the traumatic state than cinema. Here, the Captive’s mouth is covered; he cannot speak. But his eyes can; they implore our empathy. As a mostly narrative medium, film seems the least apt to do justice to the turbulent incoherence, repetitiveness, and incongruous adventures told in the novel. Nevertheless, thanks to film’s capacity for audio-visualization, something must be possible that is more in line with the difficult novel. Talking about it with actor Mathieu Montanier, we got the idea that a video installation consisting of different, non-linear episodes might instead be more effective in showing, rather than representing, not the moment trauma occurs but violence-generated traumatic states. It seemed relevant that Wittgenstein’s ending of his Tractatus (1921), “Of what one cannot speak, one should keep silent” was modified later into “Of what one cannot speak, one can still show”.⑩The importance of showing is to enablewitnessingas an engaged activity against the indifference of the world. The theatricality of this display helps to turn onlookers and voyeurs into activated, empathic witnesses. This transforms the cultural mode of dealing with trauma. To achieve this, “image-thinking” is an important mode.

Image-Thinking for a Thought-Image of Trauma

This need to stage empathic witnesses to the trauma that violence generates, as well as the generalizing, even abusive use of the term, has led me to rethink trauma, especially for the term’s use in cultural analysis. The preceding photograph, as an image, is more “telling” than any images “of” or “on” trauma I have seen. Briefly, I articulate the issue of trauma not in a single but in a triple form:

Violence— an event, perpetrated by subjects

Trauma— a state, which imprisons the victims of the violence, who remain deprived of temporality

Empathy— an attitude that can help

For this, I learned from Cervantes; to be specific: from his masterly novel’s (lack of?) form. My first intuition suggested that, in order to do justice to the peculiar, cyclic, perhaps even “hysterical” form of the novel while pursuing these two goals of showing and, or for, witnessing, only an equally “incoherent”, episodic artwork can be effective. But this artwork must exceed a plain similarity of form. It needs to yield “thought-images” orDenkbilder, created through the process of “image-thinking”. As it happens, the thought-image was a favourite literary-philosophical genre of the group of writers of the pre-WWII Frankfurt School of social thought. The small iconic texts Adorno, Benjamin, Kracauer, and others wrote were texts only. What did the wordBilderdo there, then? This is where “image-thinking” can meet, and yield, “thought-images”. In a study of the genre, California-based scholar of German Gerhard Richter begins his description of the genre with a whole range of negativities: “Denkbilderare neither programmatic treatises nor objective manifestations of a historical spirit, neither fanciful fiction nor mere reflections of reality” (2).

These negatives have something in common. Indeed, every category that is negated here is inapplicable because it is one side of a binary opposition. A programmatic treatise would be something like a political pamphlet, as opposed to historical objectivations — an opposition that audio-visual art is devoted to questioning. The second pair is equally subject to the reductions of binary opposition: what Richter disparagingly calls “fanciful fiction” stands opposed to an equally dismissed “mere reflections of reality”. And while mobilizing both words and images, video art does not pitch them against each other at all. “Rather”, Richter continues with a formulation that is promising for the idea of image-thinking: “the miniatures of the Denkbild can be understood as conceptual engagements with the aesthetic and as aesthetic engagements with the conceptual hovering between philosophical critique and aesthetic production” (2).

“Hovering” recalls J.L. Austin’s use of the verb when describing the ambiguity of fire as hovering between thing and event. Integrated with the Freudian concept of “working through”, I suggest the metaphor of weaving, mutually engaging on all levels.In writing, these pieces are miniatures, like Adorno’s aphorisms published asMinimaMoralia:ReflectionsfromDamagedLife, written between 1944 and 1946 — ominous dates.They can also be short fragments, like Benjamin’s reflection in a childhood memory, on the ball of socks in his cupboard, where the packaging disappears as the content, the socks, unfolds. Most of all, given the following part of Richter’s definition, this resonates with Benjamin’s fifth thesis on images of the past, which has been a guideline for my work on art between history and anachronism: “[E]very image of the past that is not recognized by the presentasoneofitsownconcernsthreatens to disappear irretrievably” (255). This warning that the images of the past threaten to get lost irretrievably if we ignore their relevant for today, is crucial for our project; it is one of its main motors.

Richter describes the thought-image thus: “The Denkbild encodes a poetic form of condensed, epigrammatic writing in textual snapshots, flashing up as poignant meditations that typically fasten upon a seemingly peripheral detail or marginal topic” (2). The word “flashes up” suggests the quick flash that Benjamin urges us to preserve by means of recognition in the first sentences of that thesis V from which I now quote a later sentence: “The true picture of the pastflitsby. The past can be seized only as an image whichflashesupat the instant when it can be recognized and is never seen again” (255; emphasis added). This articulates quite precisely why and how we seek to revitalize Cervantes’s novel for today. We do it, not in a linear film but in “flashes”: short, 8-minute video clips.

It also connects to the question of historical truth, the issue at stake in the episode “Who is Don Quijote?”. In this regard, in hisAestheticTheoryAdorno writes:

What cannot be proved in the customary style and yet is compelling — that is to spur on the spontaneity and energy of thought and, without being taken literally, to strikesparksthrough a kind of intellectualshort-circuitingthat casts a sudden light on the familiar and perhapssetsitonfire. (322—23, emphasis added)

As in Benjamin’s thesis, the language here is again both visual and shock-oriented, with “sparks”, “short-circuiting”, “sudden light” and “sets it on fire”. This is thought alive, and this living thought is active. It has agency. And it is visual. Thought needs a formal innovation that shocks. Thus, it can gain new energy and life, involve people, and make thought a collective process rather than the kind of still images we call clichés. Our attempt to achieve such “sparking”, shocking innovation lays in the combination of material, practical changes of the mode of display, the anachronistic bond between present and past, the confusion of languages and other categories we tend to take for granted, and above all, the trans-mediation, the intermediality of the audio-visualization of a literary masterpiece. In view of the need for witnessing, such a messy “thinking” form enables and activates viewers to construct their own story, and connect it to what they have seen around them. Thus, we aim to turn the hysteria of endless story-telling into a reflection on communication as it can breach, and reach beyond, the boundaries that “madness” — to use a generic noun in order to avoid the diagnostic discourse that leads to medicalization and hospitalization instead of resocialization — draws around its captive subjects, and instead, open up their subjectivity. “Mad” is also a way to characterize Cervantes’s novel while acknowledging his traumatizing experience along with his literary genius. This adds, and gives more depth to the interpretation, advanced by some scholars, of the novel as bound to the carnivalesque late-medieval culture Bakhtin has put forward, while also foreshadowing the modern novel. In my view of history as by definition anachronistic or, as I call it with a wink, “pre-posterous” (see note 14), it can even be connected to postmodern aesthetics. The production of a thought-image of trauma as a state and empathy as a potential remedy required a “mad” form.

Forms of Formlessness

To accomplish this, we speculated that singular installation pieces might facilitate experimenting with the episodic nature of the literary masterpiece. In line with this expectation Mathieu Montanier and I designed the pieces together, in a dialogue between actor-artist and academic-artist. This turned out an ideal combination of minds for the process of image-thinking towards thought-images. These pieces, presenting “scenes”, propose situations. To give insight into the stagnation that characterises the adventures, they are predominantlydescriptiverather than narrative. Any attempt at narrative is “stuttering”, recurring, without any sense of development. The scene “Narrative Stuttering” shows both the incapacitation to narrate and the frustration this causes. Hence, my beginning with this episode, as my academic version of “in medias res”.

5. Don Quijote’s narrative stuttering. Photo: Mar Sez

Just a few examples of formless forms. Sometimes, the images do not match the dialogues. What the French psychoanalyst and theorist of trauma and the resulting madness, Françoise Davoine, calls, citing historian Fernand Braudel: “poussières d’événements” (dust of events) is the motto of this work’s form: sprinkling situations, moments, over the stage or throughout the gallery space. Thus, the tenuous line of a single narrative yields to an installation that will put the visitors in the position of making their own narrative out of what is there, on the basis of their own baggage, while witnessing events without chronological linearity. Instead, they determine their own video-hopping throughout their visit. They can sit through several cycles or just watch for a few moments, according to what the videos make them feel; how they affect them. This lack of chronology is adequate to the state of trauma presented in the pieces and in the juxtapositions among them, and to the need to stretch out a hand to, instead of turning away from people hurt so deeply that they seem so different we dismiss them as “mad”. The disorderly display gives a shape, however unreadable and unclear, to the trauma-induced madness of the novel’s form.

Cervantes, I presume, was one of those “mad” ones, whether or not he was able to hide it. The trauma incurred by Cervantes after being held in captivity as a slave without any sense of an ending to his disempowered state and his suffering, has been beautifully traced in his writings, narrated, and explained by Colombian literary historian María Antonia Garcés. This traumatic state looms over the entire project, and determines its form. Therefore, we tried something we never do, and which in my academic work is almost a taboo: completely merging the author’s biography, the main character’s ostensive and much commented-upon madness, and the central character of one narrative unit we selected for a more extensive narrative element, “The Captive’s Tale”. Supported by Garcés’s refined and detailed, well-documented analysis, we can only see a haunting autobiographical spirit in the three chapters on the Captive. But the shape of the theatrical display in which the scene is set does not “re-present” the madness. It hints at it, makes us reflect on it.

TheDenkbildis in the form that makes the live thinking visible. The form of these pieces is experimental in many different ways, so that a contemporary aesthetic can reach out to, and touch, a situation of long ago that, as befits the stilled temporality of trauma, persists in the present. In practical terms of cinematography, the main characteristics of the pieces and of the entire installation, are the effects of our “image-thinking”. Long, enduring shots predominate; some episodes consist of single shots. Sound-wise, some are quiet, some loud. This allows the simultaneity, the proximity, of different scenes, without avoiding sound interference and avoiding the use of headphones which isolate visitors from one another. Another experimental form concerns the dynamic relationship between visibility and invisibility, image and writing. A deployment of voice-off without synchronicity with the images —— also a novelty in our work —— foregrounds this tension. The actor Mathieu Montanier, initiator of the project, is visible, but so are, sometimes, the letters of inscriptions, in association with other texts, to foreground the nature of video-graphyas a form of writing. The fragments read by Davoine in voice-off, break the realism of perfect synchronisation. In short, through experimenting with possible forms of the art of video, we seek to invent new forms for the formlessness of trauma.

The resulting disorderly installation embodies that form; it is its thought-image. Following the thinking in George Kubler’s concept ofTheShapeofTimeand Thomas McEvely’sTheShapeofAncientThought, by means of image-thinking this installation would have to answer to the paradoxical concept or thought-image oftheshapeofformlessness. The paradox vanishes, however, once we recognize the ontology of form. There is no real formlessness as soon as something exists. The installations created so far, in Småland and in Murcia, offer examples of such formless forms. Whereas the former was set in a space with dark brick wall, the latter was bright with white as the predominant colour. And as these photographs show, the formlessness does have a form. Disorderliness is not formless. On the contrary, in this case, where short videos and still photographs constantly solicit both restful watching and restlessness, it is a live form. The juxtaposition of moving and still images is only one element of the form, but an important one. On the whole, the form is one that embraces the visitors’ freedom to shape the space in their own way, by means of their mobility and the temporality of their choice. Nothing that is, can really be formless.

6. Porridge: Porridge is a soft food made by boiling oatmeal or other meal or legumes in water or milk until thick (WordNet). Note that the bears are not introduced as carnivorous. The concept that they have cooked porridge for their meal, as well as the other clues of civilized behavior, lessens21 the anxiety over Goldilocks welfare during the story.Return to place in story.

Notes

① The exhibition is also an example of the creativity that can be generated by the experience of generosity and solidarity. My deepest gratitude goes to Niklas Salmose (niklas@trolltrumma.se) who can provide the complete book about the exhibition. I am also very grateful to Nicolas Hansson, chief curator at the Småland Museum, to Jonas Valthersson for excellent camera work, to Ebba Sund for brilliant photographs, and to the many colleagues and students at Linnaeus University who have given precious help.

② Here, my gratitude goes to Jesús Segura, who did 75% of the camera work and curated the exhibition, and to Luz Baón, who translated the book and assisted with the installation, photographed both many of the scenes during filming and the opening of the show. Also, to Isabel Durante who organized the filming so effectively that we could do more than expected in just one week. And again, to colleagues and students who volunteered their talents and time.

③ “In medias res” is an old narratological category that dates back to classical antiquity. It is also the title of my book on the shadow-plays of Indian artist Nalini Malani, which are, as I argue there, exemplary of the need for “immersive viewing”. SeeInMediasRes:InsideNaliniMalani’sShadowPlays. Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2016.

④ See Kati Röttger, “The Mystery of the In-Between: A Methodological Approach to Intermedial Performance Analysis.”ForumModernesTheater28.2(2018): 105—16.

⑤ See also Maaike Bleeker.VisualityintheTheatre:TheLocusofLooking. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008. In these publications Bleeker demonstrates, through detailed analyses, how productive such a concept of theatricality can be for a political art that is not bound to a political thematic.

⑥ For an excellent relevant critique of the concept of “artistic research”, see Vellodi, Kamini. “Thought Beyond Research: A Deleuzian Critique of Artistic Research.”AberrantNuptials:DeleuzeandArtisticResearch2. Eds. Paulo de Assis and Paolo Giudici. Leuven: Leuven University Press (215—33). On this search in Leonardo’s work, see Fiorani, Federica and Alessandro Nova, eds.Leonardo’sOptics:TheoryandPictorialPractice. Venice: Marsilio Editore, 2013. Ernst van Alphen proposed the concept of “image-thinking” as a counterpart to “thought-images”, an idea for which I am very grateful. His concept, in the form of a verb, is more dynamic, rendering the interaction between thinking and imaging more forcefully (personal communication, August 2019). The term “artistic research” has been established in a sense that confines it to artists who are interested in earning a PhD, whereas the opposite itinerary —— my own, of academics who seek to explore the added value of the imagination for their work more thoroughly —— is excluded from what has become hierarchical.

⑦ A useful, accessible volume of short studies onCervantes’snovelisCervantes’DonQuixote:ACasebook. Ed. Roberto Gonzlez Ecevarría. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. For the other “theoretical fictions” I have (co-)made, see http://www.miekebal.org/artworks/films/a-long-history-of-madness/; http://www.miekebal.org/artworks/films/madame-b/;http://www.miekebal.org/artworks/films/reasonable-doubt/.

⑧ For the most lucid analysis of the reasons for the unrepresentability of trauma, specifically in relation to narrative, see Alphen, Ernst van. “Symptoms of Discursivity: Experience, Memory, Trauma.”ActsofMemory:CulturalRecallinthePresent. Eds. Mieke Bal, Jonathan Crewe, Leo Spitzer. Hanover, NH: University of New England Press, 1999.24—38.

⑩ See the final sentence of Wittgenstein, Ludwig.TractatusLogico-Philosophicus. Trans. David Francis Pears and Brian McGuinness. New York and London: Routledge, 2001. On his change of opinion seePhilosophicalInvestigations#41, commented on by Françoise Davoine and Jean-Max Gaudillière, 17,51—52 inAbonentendeur,salut!Facelaperversion,leretourdeDonQuichotte. Paris, Stock, L’autre pensée 2013, who quote O’Drury, Maurice.ConversationsavecLudwigWittgenstein. Trans. J.-P. Cometti. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2002.159,170,173.

Works Cited

Adorno, Theodor W.AestheticTheory. Trans. Robert Hullot-Kentor. London: Athlone Press, 1997.

Benjamin, Walter.Illuminations. Ed. Hannah Arendt. Trans. Harry Zohn. New York: Schocken Books, 1968.

Bleeker, Maaike. “Being Angela Merkel.”TheRhetoricofSincerity. Eds. Ernst van Alphen, Mieke Bal, and Carel Smith. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008.247—62.

Richter, Gerhard.Thought-Images:FrankfurtSchoolWriters’ReflectionsonDamagedLife. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007.

Röttger, Kati. “The Mystery of the In-Between: A Methodological Approach to Intermedial Performance Analysis.”ForumModernesTheater28.2(2013): 105—16.