Abdominal pain related to adulterated opium:An emerging issue in drug addicts

Maryam Vahabzadeh, Bruno Mégarbane

Maryam Vahabzadeh, Medical Toxicology Research Center, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran

Bruno Mégarbane, Department of Medical and Toxicological Critical Care, Lariboisière Hospital, Paris-Diderot University, INSERM UMRS-1144, Paris 75010, France

Abstract

Key words:Addiction;Opium;Lead;Poisoning;Abdominal pain;Toxicity

INTRODUCTION

Toxicity from heavy metals can occur following their overload in the body due to exposure to various sources.Considered as one of the highly toxic heavy metals, lead is naturally available in metallic and organic forms and can interfere with the function of several organs such as the central nervous system, the liver, the kidneys, the hematopoietic and cardiovascular systems[1].Different sources of exposure are responsible for lead toxicity in humans, mainly drinking water, paint, occupational exposure and leaded gasoline[2].Metallic lead can enter the bodyviaingestion(depending on the age and nutritional status) and inhalation (depending on the particle size)[3].However, the majority of lead poisonings are due to ingestion and its consequent absorption occurs in the smaller intestine resulting in its accumulation in blood, bone, and fatty tissues[4].

Also known as plumbism, lead poisoning is still one of the main areas of concern in the developing world including Iran.Even though cases due to occupational lead poisoning have declined, overall metallic lead poisoning has markedly increased over the past few years[5].

Lead poisoning is difficult to diagnose due to non-specific manifestations.The main symptoms and signs include moderate-to-severe abdominal pain (also known as lead colic), appetite loss, constipation, anemia, liver and renal function impairment, and neurologic complications.Major risk factors for lead toxicity are young age (children),lack of minerals and protein in the diet, as well as poor socioeconomic conditions[4].However, another notable major and recently recognized risk factor for lead poisoning is addiction to opium.

Lead poisoning due to abuse of contaminated opium was first reported in 1970s[6,7]and subsequently in 1989 following lead-contaminated heroin[8].Interestingly, lead poisoning has been reported from lead-contaminated opium available in the Iranian market[9]while opium samples were confirmed to be contaminated with lead in Kerman province of Iran[10].Failure to detect or misdiagnosis of lead poisoning in patients with a history of opium addiction presenting with abdominal pain may result in time-consuming gastrointestinal work-ups or even unnecessary abdominal surgery[11].The current paper aims to review abdominal pain as the leading emergent symptom of lead poisoning referring opiate addicts to healthcare facilities.To address this goal, we reviewed all published cases and series of adult drug addicts presenting with abdominal pain attributed to lead poisoning from lead-adulterated opium.

LEAD TOXICITY

Chemical properties of lead

Lead is a bluish-gray silvery metal with atomic number of 82 and two isotopes206Pb and208Pb, and is available in two forms of metallic (also called inorganic) and organic lead (tetraethyl and tetramethyl lead).Lead has no particular taste or smell, and at atmospheric pressure, melts at 621.3 °F (327.4 °C), and boils at 1740 °C[12].

Exposure to lead

Exposure to lead may result in multisystemic toxicity.The risk of exposure to lead is higher among children and those with certain occupations.However, lead exposure in the workplace alone does not count as significant source of poisoning[13].

Upon exposure, lead is mainly absorbed from the gastrointestinal and respiratory systems.Over days to years, it accumulates in the body, particularly in bones, before manifestations occur.Also known as plumbism, lead poisoning is defined as abnormally elevated concentrations of lead in the blood resulting in non-specific symptoms and signs.Depending on the severity of poisoning, it can cause gastrointestinal manifestations such as abdominal pain and constipation, in addition to anemia, impairment of the nervous system, liver, kidney, heart, and reproductive system as well as developmental impairment in children.The exact mechanism by which lead exerts its toxic effects on the GI is not yet known.However, some theoretical mechanisms are change in luminal ion transport, impairing intestinal motility, and spasmodic contractions in smooth muscles of the intestinal wall.The latter is considered to be one of the major causes of abdominal pain in lead-poisoned patients.The limit of concern for blood lead level (BLL) in children is 5 µg/dL, while it is much higher for adults (above 25 µg/dL)[14].

Over the past decade, one concerning source of exposure to lead was reported to be lead adulterated opium in Iran, although identified last century[6,7].Iran lies in the major pathway of opium trafficking in the Middle East.According to the United Nations Office on Drug and Crime, 74% of the world opium seizures and 25% of the world heroin and morphine seizures in 2012 occurred in Iran[15].Therefore, opium addiction is one of the major governmental and health challenges in the country.Although not yet widely reported, lead-contaminated opium has caused increasing numbers of poisonings to be referred to emergency departments and clinical toxicology centers.

REVIEW OF LEAD POISONING REPORTS DUE TO ADULTERATED OPIUM

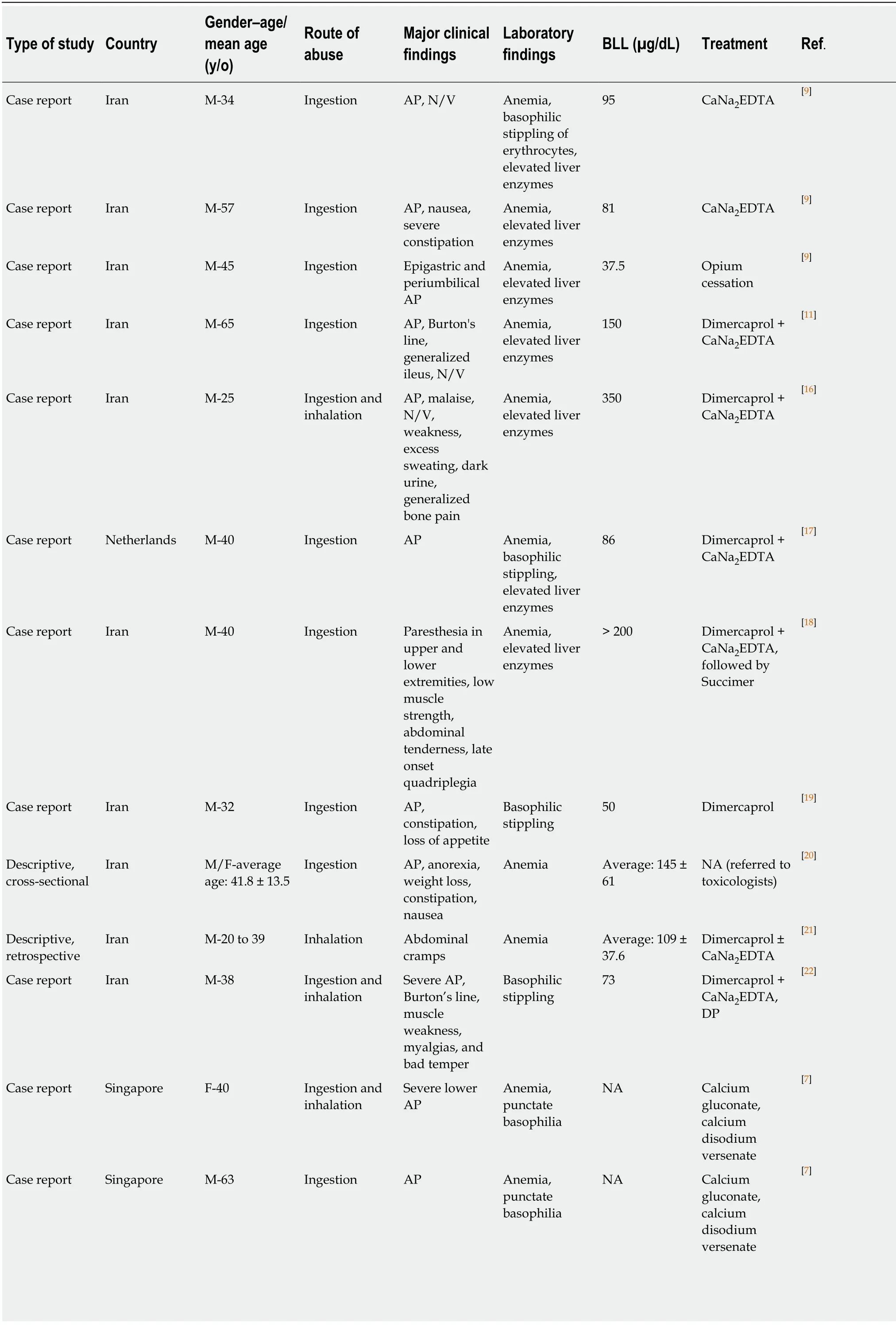

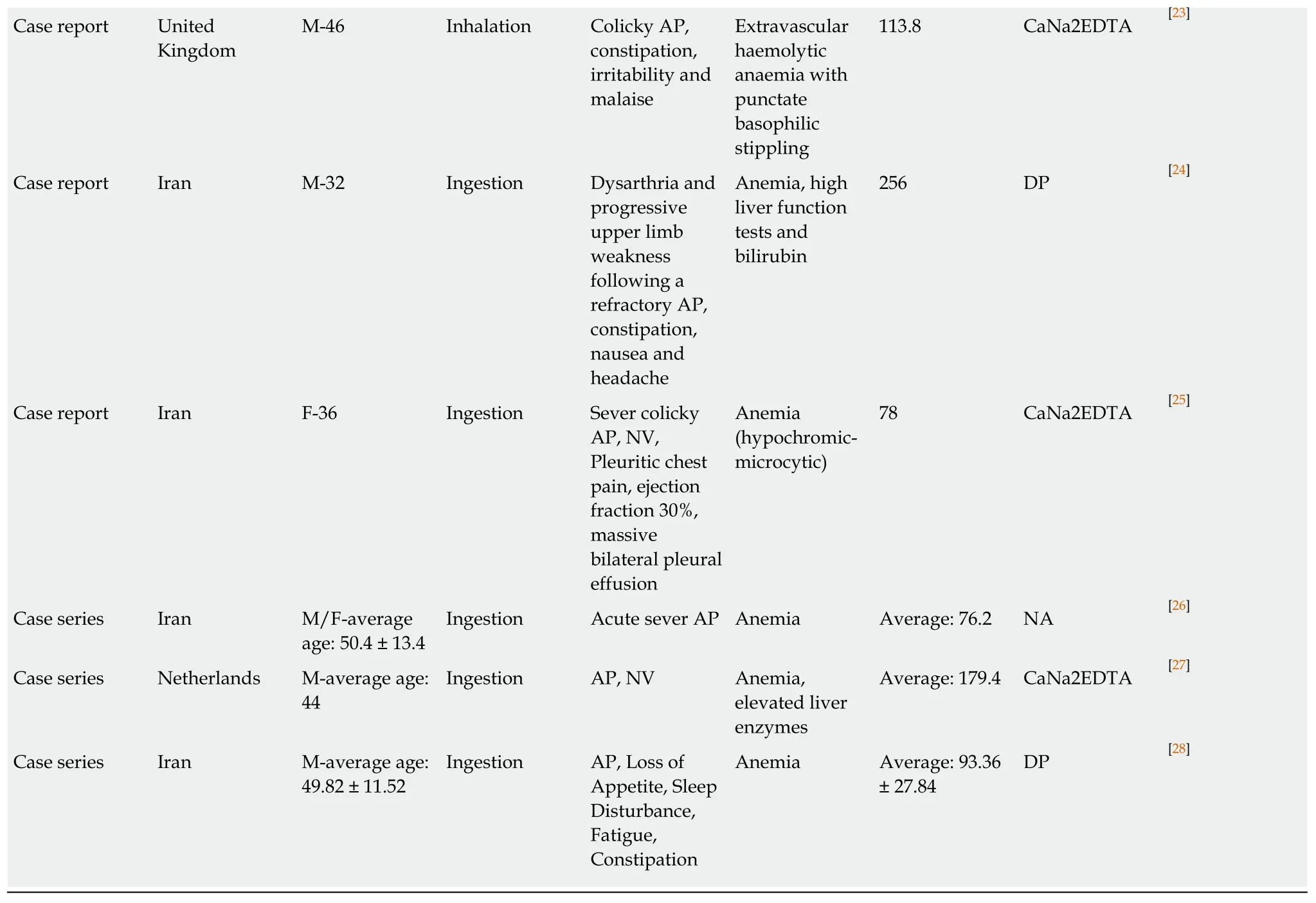

Masoodiet al[9]first reported three male patients from Iran with acute abdominal pain,abnormal liver function tests, and anemia due to chronic oral opium use.None of the patients had occupational exposure and their chief complaint was abdominal pain and varying degrees of constipation.All patients were withdrawn from opium while two with BLLs above 80 µg/dL received chelating agent (CaNa2EDTA).All were asymptomatic with normal laboratory tests after 3-4 wk of follow-up.

Further reported cases of lead poisoning due to lead-contaminated opium are depicted in Table 1, with the country of patient origin and additional clinical and laboratory data.

As shown in Table 1, the majority of cases of lead poisoning due to leadcontaminated opium[9,11,16-28]are surprisingly reported from Iran with the dominance of men.The case reports from The Netherlands[17,27]and the United Kingdom[23]also concerned two Iranians, one immigrant abusing opium from Iranian suppliers and one Persian citizen addicted to inhalational opium, respectively.

According to Table 1, the main features of lead poisoning are portrayed as gastrointestinal, hepatic and hematologic disorders.Manifestations in opium abusers were clearly attributable to the elevated BLL in comparison with non-addicts;hence,determination of BLL in suspected cases can definitively confirm the diagnosis[29].Although abdominal pain is usually seen with BLL above 80 µg/dL, these reports are good evidence for the assumption that occurrence of abdominal pain, is not related to BLL[25].On the other hand, there was a significant correlation between BLL and duration of drug abuse in opium addict cases (r=0.398,P=0.022).The odds ratio of having BLL ≥ 100 µg/dL in oral opium users was 2.1 (95%CI:0.92-4.61;P=0.43)[30].

It is not exactly known how much lead is added to opium samples in the Iranian black market.However, chemical analysis of a sample by atomic absorption spectrometry, recognized as the method of choice, showed 35.2 mg of lead per 100 g of opium[19].In another study from Iran, random samples from various sources were analyzed using atomic absorption spectrometry, and the mean concentration of lead in the samples was 1.88 ± 0.35 ppm[10].Chiaet al[7]reported the level of lead in contaminated opium samples to be 33.8 mg per 100 g of opium.

Chronic abuse of opium with such low levels of lead over months to years results in lead accumulation and consequently severe plumbism.This poisoning can be easily misdiagnosed as it mimics several other medical conditions such as surgical acute abdomen, withdrawal symptom, crisis of sickle cell anemia, cholecystitis, acute porphyria, and nephrolithiasis[20,31].Therefore, lead poisoning should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with moderate to severe abdominal pain.

All symptomatic patients with high BLL should undergo treatment following medical consultation with a clinical toxicologist.The treatment plan essentially consists of oral opium cessation, probably with the help of rehab programs, in addition to the administration of chelating agents such as dimercaprol (BAL:British anti-lewisite), CaNa2EDTA, succimer (DMSA:dimercapto-succinic acid), and more rarely D-penicillamine[2].Decision on which chelator should be used depends on the BLL, clinical manifestations, and laboratory results[14].

Complications of lead poisoning are reversible, providing early diagnosis and appropriate treatments are made;however, neurotoxicity may be permanent following significantly elevated BLLs and delayed specific treatment[18].Timely detection and proper therapies for lead poisoning in an opium-addicted individual with the chief complaint of abdominal pain cannot only obviate the need forunnecessary medical evaluations or procedures and decrease its perilous complications such as loss of consciousness and paralysis[32]but also reduce the financial burden on patients and healthcare systems.

Table 1 Reports of lead poisonings due to adulterated-opium abuse and their supplementary data

M:Male;F:Female;N/V:Nausea and/or vomiting;AP:Abdominal pain;BLL:Blood lead level;NA:Not available;DP:D-penicillamine.

CONCLUSION

Despite a decrease in the frequency of occupational lead poisoning, a new trend of lead poisoning has recently emerged among opium addicts, mainly in Iran.Because of non-specific manifestations and hazardous effects of lead poisoning, this critical poisoning should be considered in the medical approach to any patient with a history of opiate addiction presenting to the emergency department with acute abdominal pain and particularly colicky abdominal pain.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Mrs Alison Good, Scotland, United Kingdom,for her helpful review of this manuscript.