Post-transplant diabetes mellitus and preexisting liver disease - a bidirectional relationship affecting treatment and management

Maja Cigrovski Berkovic, Lucija Virovic-Jukic, Ines Bilic-Curcic, Anna Mrzljak

Abstract Liver cirrhosis and diabetes mellitus (DM) are both common conditions with significant socioeconomic burden and impact on morbidity and mortality. A bidirectional relationship exists between DM and liver cirrhosis regarding both etiology and disease-related complications. Type 2 DM (T2DM) is a wellrecognized risk factor for chronic liver disease and vice-versa, DM may develop as a complication of cirrhosis, irrespective of its etiology. Liver transplantation(LT) represents an important treatment option for patients with end-stage liver disease due to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which represents a hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome and a common complication of T2DM. The metabolic risk factors including immunosuppressive drugs, can contribute to persistent or de novo development of DM and NAFLD after LT.T2DM, obesity, cardiovascular morbidities and renal impairment, frequently associated with metabolic syndrome and NAFLD, may have negative impact on short and long-term outcomes following LT. The treatment of DM in the context of chronic liver disease and post-transplant is challenging, but new emerging therapies such as glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) targeting multiple mechanisms in the shared pathophysiology of disorders such as oxidative stress and chronic inflammation are a promising tool in future patient management.

Key words: Diabetes mellitus; Liver transplantation; Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease;Metabolic syndrome; Insulin-resistance; Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists;Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus (DM) represents a group of heterogeneous diseases caused by an impaired insulin secretion and/or action. It is characterized by hyperglycemia and derangements in carbohydrate, lipid and protein metabolism, causing the development of numerous complications resulting in increased morbidity and mortality of patients[1]. According to the World Health Organization data, 422 million adults live with DM worldwide and global prevalence is estimated to rise to 592 million by 2035[2,3].

The liver has a key role in glucose metabolism. It is responsible for the maintenance of total carbohydrate stores and for gluconeogenesis. Regulation of the complex and interdependent glycolytic-gluconeogenic pathways is dependent on multiple factors,including hormonal status and the relative availability of nutrient substrates[4].

The association between DM and liver disease is well established and complex in nature. Insulin resistance (IR) and type 2 DM (T2DM) within the metabolic syndrome are important risk factors for the development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease(NAFLD), non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), liver fibrosis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[5]. On the other hand, liver cirrhosis of any etiology can cause impaired glucose regulation due to diminished liver function, and the term hepatogenous diabetes has been proposed for this entity[6,7]. However, it is sometimes difficult to establish this diagnosis, due to the aforementioned bidirectional relationship between impaired glucose metabolism and chronic liver disease.

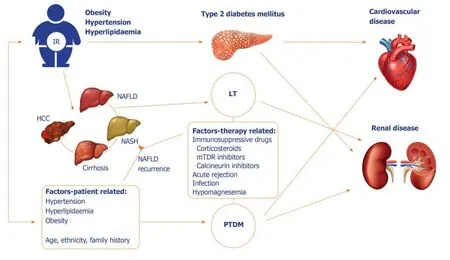

Liver transplantation (LT) is a well-established treatment option for end-stage liver disease of any etiology. Following LT, glucose metabolism can improve and DM resolve, especially in patients with diabetes following liver cirrhosis development.However, this may not be true for patients with pre-existing diabetes, and to further complicate this relationship, DM may develop post-transplant, due to genetic factors and lifestyle changes of the patient, immunosuppressive treatment, donor-dependent and procedure-related factors (Figure 1).

The complex relationship and mechanisms involved in the interplay between DM and liver disease before and after LT will be explored, and related to management issues, newer treatment options and patient outcomes.

NAFLD

The global prevalence of metabolic syndrome characterized by the morbidity cluster of obesity, T2DM, hypertension and dyslipidemia is rapidly rising, reflecting the changes in eating habits and inclination towards sedentary lifestyle. In parallel, its liver manifestation NAFLD is becoming the most common cause of chronic liver disease and the leading cause of liver-related mortality[8]. The global prevalence of NAFLD is now estimated around 25%, the highest being in South America and in the Middle East (30%-31%) and the lowest in Africa (13%)[9].

Figure 1 A complex relationship between liver disease and diabetes mellitus. Although in case of diabetes mellitus following liver cirrhosis glycemia might improve after liver transplantation (LT), this may not be the case in the preexisting type 2 diabetes mellitus. Moreover, diabetes can develop following LT (posttransplant diabetes mellitus) due to different patient and procedure-related factors. Both diabetes and liver disease after transplant increase the cardiovascular risk,which is the main cause of mortality in the long-term follow-up. LT: Liver transplantation; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; PTDM: Post-transplant diabetes mellitus; IR:Insulin resistance; NAFLD: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH: Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.

NAFLD encompasses a wide spectrum of histological changes in the liver, ranging from simple steatosis or non-alcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, fibrosis and finally cirrhosis[10]. Approximately 25% of NAFLD patients develop NASH, and 5% progress to cirrhosis. Severe liver-related events,such as death or need for LT are relatively uncommon, and occur in 1-2% of patients with NAFLD. However, given its high global prevalence, NAFLD has become the fastest growing indication for LT[11].

The pathogenesis of NAFLD is multifactorial and complex, with multiple mechanisms involved in the development and progression of the disease[12,13]. Genetic factors, dietary habits and other environmental factors lead to obesity and insulin resistance (IR), which is the key mechanism responsible for the NAFLD forming cascade of events. Impaired inhibition of adipose tissue lipolysis with consequent increased influx of free fatty acids into the liver together with increased hepaticde novolipogenesis outweigh fatty acid oxidation and triglyceride secretion, resulting in the accumulation of triglycerides in hepatocytes[12,13]. Increased lipotoxicity causes mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress and production of reactive oxygen species; these changes result in a more severe form of NASH[14]. Obesity and insulin resistance are associated with alterations in gut microbiota and changes in intestinal permeability with consequent activation of inflammatory pathways and release of proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin 1 and 6[12,13]. Changes in the secretion of adipokines, hormones derived from adipose tissue,such as adiponectin, leptin, resistin or ghrelin, contribute to chronic inflammatory state which consequently leads to further liver injury, where long-standing liver damage and repair responses result in activation of hepatic stellate cells and deposition of fibrous matrix, leading to cirrhosis and development of HCC[15,16].However, although steatosis in NAFLD usually precedes inflammation, it has been recognized that hepatic inflammation and fibrosis can exist without steatosis[12,17].Numerous and diverse processes which contribute to the development of steatosis and liver inflammation occur in parallel, and it is possible that different risk of progression of simple steatosis or NASH to more advanced liver disease may actually allude that these two are separate entities in terms of pathogenesis[12,17].

Given the high burden of NAFLD and its consequences, end-stage liver disease and HCC, NAFLD represents a growing indication for LT both in Europe and the United States. In the near future, the prevalence of NAFLD as indication for LT is expected to rise due to increasing prevalence of obesity, T2DM and metabolic syndrome, but also because of lack of symptoms and reliable non-invasive tests for the timely and accurate diagnosis, as well as lack of effective treatment options that could significantly alter the course of the disease. The problem is augmented by the reportedly high rates of NAFLD recurrence after LT, ranging between 30%-100% of NAFLD liver transplant recipients, andde novooccurrence of NAFLD in 20%-30% of patients undergoing LT for other indications[18-20].

DM AND NAFLD - CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE EQUIVALENTS?

T2DM is an important risk factor for the development of NAFLD, and vice versa.NAFLD is associated with up to five-fold increased risk of T2DM[21]. The prevalence of DM is higher (48.4%) in NASH than in other indications waitlisted for LT. Moreover,NASH patients are more likely to be white, female, older, and with higher body mass index[22]. Concomitant NAFLD in patients with diabetes often compromises achievement of desired glycemic targets and moreover aggravates complications such as chronic kidney disease by almost 2-fold; these factors later on contribute to overall poor treatment outcomes[23,24].

Available evidence suggests an intimate relationship between NAFLD/NASH,T2DM, cardiovascular disease (CVD) and chronic kidney disease[25]. This is not a surprise since NAFLD/NASH and T2DM share many metabolic risk factors with cardiovascular and chronic kidney disease, such as insulin resistance, atherogenic dyslipidaemia, hypertension and obesity. Different pathophysiological mechanisms have been described that contribute to CVD and chronic kidney disease development in patients with NAFLD/NASH and T2DM and this topic has been extensively reviewed elsewhere[25-27]. Although epidemiological evidence from many primarily cross-sectional, case-control and retrospective studies involving NAFLD patients with and without diabetes have shown an increased prevalence of CVD and chronic kidney disease, the complex interplay between the traditional cardiometabolic risk factors makes a causal relationship between NAFLD, T2DM, and cardiovascular and chronic kidney disease sometimes difficult to establish[28,29]. In the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), NAFLD proved as independent risk factor for latent atherosclerosis, chronic inflammation and coronary artery calcium scores[30]. Similarly in the Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study (KIHD), the fatty liver index was a predictor of incident CVD in the middle-aged men over a median of 17-year follow-up[31]. In addition, data coming from observational studies showed the association between NAFLD and significant increase in the risk of incident chronic kidney disease[32].

DM AND LIVER CIRRHOSIS

Liver cirrhosis represents the end-stage liver disease caused by various etiologies and mechanisms of liver injury that lead to inflammation, necrosis, and consequent fibrogenesis. It is an important cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, with significant regional differences in both the prevalence and etiology of the disease.Cirrhosis represents the 14th most common cause of death in adults and results in 1.03 million deaths per year[33].

T2DM and IR are important risk factors for the development of NAFLD and NASH, which can progress to liver cirrhosis. On the other hand, IR and hyperinsulinemia are common features in cirrhosis[6,34]. Recent studies using current criteria for DM diagnosis have shown that, based on fasting plasma glucose levels,alone or associated with measurements of hemoglobin (Hb) A1c, prevalence of DM in cirrhotic individuals is approximately 30%-40%, but if individuals were subjected to an oral glucose tolerance test, the prevalence of abnormal glucose tolerance and DM would rise up to 96%[35].

Although it has been recognized that liver cirrhosis of any etiology represents a risk factor for the development of DM, the mechanisms responsible for the development of cirrhosis-associated DM are multiple and not completely understood[6,7]. A body of evidence suggests that liver dysfunction in cirrhosis directly affects insulin secretion,clearance and insulin sensitivity, but certain etiological agents may cause IR in the earlier, pre-cirrhotic stages, through various mechanisms[6,36-39].

Numerous epidemiological, clinical and experimental studies have reported hepatitis C virus to be strongly associated with hepatic steatosis, IR and T2DM, even before cirrhosis development[40]. HCV induces IR in the liver and peripheral tissues through multiple mechanisms. A large meta-analysis of 34 studies confirmed a positive correlation between HCV infection and increased risk of T2DM in comparison to the general population[41,42]. The prevalence of T2DM was also reported to be higher in patients with chronic hepatitis caused by HCV compared to subjects with chronic liver diseases from other etiologies[6,43]. However, prevalence of T2DM was higher in HCV infected patients following cirrhosis development, compared to earlier stages of fibrosis, and was similar to patients with cirrhosis of other etiologies,thus suggesting that diabetogenic potential of liver dysfunction was even higher than that of hepatitis C virus itself[6]. HCV related IR and steatosis appear to be associated with progression of fibrosis and development of hepatocellular carcinoma[40].

Alcohol is known to reduce insulin-mediated glucose uptake upon acute ingestion,although the effects of chronic alcohol intake are less well understood[44]. Patients with chronic consumption of alcohol frequently suffer from chronic pancreatitis and damage to pancreatic islet β-cells can result in diabetes development[44]. The risk of developing DM seems to be related to the amount of alcohol ingested and increased twofold in persons with high alcohol intake compared to those with moderate intake[45]. Prevalence of diabetes among patients with alcohol-related liver cirrhosis according to studies ranges between 10% and 40%, with an average prevalence of around 27%[46].

Hereditary haemochromatosis is a metabolic disorder characterized by iron accumulation and deposition in several organs. Haemochromatosis as well as alcohol consumption induce iron deposition in the liver which could interfere with the ability of insulin to suppress hepatic gluconeogenesis. However, the pathogenesis of diabetes due to haemochromatosis has also been related to concomitant injury of pancreatic βcells caused by iron deposits[6]. For this reason DM represents a clinical manifestation of haemochromatosis, and can be found in 40% do 85% of patients in advanced stages[44,47,48].

Unlike chronic HCV infection, the relationship between hepatitis B virus infection(HBV) and insulin resistance has not been completely understood as the studies produced conflicting results[49]. However, most studies concur that the incidence of DM in patients with HBV infection is not increased compared to patients without infection indicating that HBV may not influence the development of DM[49]. However,a meta-analysis comprising results of 15 studies found that the prevalence of T2DM among HBV infected patients was 1.3 times higher and concluded that chronic HBV infection does increase the risk of T2DM development[50]. The prevalence of DM is higher among patients with HBV who developed cirrhosis (22.2%), compared to those without cirrhosis (12.8%)[51]. The pooled prevalence of DM in patients with HBVrelated cirrhosis was around 22.2% (ranging from 9.4% to 35.0% in various studies)[46].This was significantly lower than in patients with cirrhosis related to NAFLD which had the highest prevalence of DM (a pooled estimate of 56.1%), or alcohol-related,HCV or cryptogenic cirrhosis (estimated prevalence ranging from 27.3% to 50.8%).The lowest prevalence of DM was found in patients with cirrhosis secondary to cholestatic liver disease (overall 7.1%, ranging from 1.3% to 15.2%)[46].

Regardless of the etiology of cirrhosis, and irrespective of which developed first,when cirrhosis and DM coexist, they interfere with each other with reflection on course of the disease. In a population-based Italian study, the risk of death from cirrhosis was significantly higher among patients with DM[52]. A number of prospective and retrospective studies indicated that complications of liver disease(spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and other bacterial infections, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, and gastrointestinal hemorrhage) as well as death rates are higher in cirrhotic patients with DM compared to non-diabetic patients with advanced liver disease[6]. Moreover, DM associated with poor glycemic control (HbA1c > 9%) is an independent risk factor for development of HCC in patients with chronic liver disease[53]although poor glycemic control in cirrhotic patients is not necessarily reflected through high HbA1c, but rather higher glucovariability[54]. Therefore, both uncontrolled and controlled T2DM as well as glucose intolerance can negatively impact survival of patients with liver cirrhosis[52,55]. The mechanisms involved are still not clear. Plausible explanation is that insulin resistance alone, even without the element of hyperglycemia increases adipokine production through chronic inflammation, such as leptin and TNF alpha leading to activation of TGF beta1, a profibrotic cytokine in turn activating hepatic stellate cells to produce high quantities of collagen and extracelullar matrix proteins. Of course, all these unfavorable effects of chronic inflammation mediated through IR are then largely potentiated by chronic hyperglycemia[56-61].

POST-TRANSPLANT DM

Post-transplant DM (PTDM) has been recognized as a major complication after LT with the potential for serious consequences and ultimately worse patient and graft survival[62]. It seems that in case of LT, the onset of PTDM is rapid; 50% of cases occurring within first 6 months and 75% after 12 mo following procedure[63]. Although IR and DM related to liver dysfunction and cirrhosis can improve following LT, the presence of metabolic syndrome and extrahepatic comorbidities, as well as immunosuppressive drugs can contribute to persistent orde novoDM following LT. It occurs in 7%-45% of liver transplant recipients and is associated with increased morbidity, health care costs and impairs both patient and graft survival[62-64]. So far,parameters such as advanced age, ethnicity, family history, body mass index, hepatitis C virus infection and immunosuppressive drugs (mainly corticosteroids and tacrolimus) have all been reported as risk factors for PTDM after LT[65,66]. Moreover,obesity, either predating or gained after transplantation, is associated with an increased risk for PTDM but also post-transplant NAFLD[67]. According to 2014 International Consensus Meeting diagnosis of PTDM can be established in patients after achieving stable doses of maintenance immunosuppressants, with stable allograft function, once they have been discharged from the hospital to avoid misdiagnosis of transient hyperglycemia[64]. Preferred criteria to diagnose PTDM(either fasting plasma glucose > 7 mmol/L, random plasma glucose > 11.1 mmol/L accompanied by symptoms or 2-hour post 75g oral glucose test plasma glucose > 11.1 mmol/L) are those of American Diabetes Association/World Health Organization criteria for the diagnosis of diabetes, and HbA1c > 6.5% should not be used alone to screen for PTDM within the first year after transplant.

As we enter an era where recurrent hepatitis C after LT becomes a rare entity andde novoor recurrent NAFLD increases in incidence, we are likely to see changes in the patterns of incidence and impact of PTDM. Current data suggest that PTDM increases the risk of infection, chronic renal failure, biliary complications and decreases survival[68,69]. Poor LT outcomes seem not only to be related to PTDM, but also to much earlier derangements in the pathophysiology of hyperglycemia, during IR stage[70].Still, nearly 30% of deaths in LT patients are caused by cardiovascular or cerebrovascular diseases[71].

NAFLD AFTER LT

After LT, NAFLD/NASH may re-occur or developde novo. Histological features of recurrent orde novoNAFLD/NASH are the same as in native livers, and there are no features to differentiate recurrent fromde novoNAFLD/NASH in the graft. The diagnosis is based on correctly identifying preexisting liver disease - NASH-related or in some cases cryptogenic cirrhosis[72]. The studies assessing NAFLD recurrence after LT report a wide range from 10 to 100%[19,20,73-75]. However, regardless of indication for LT, risk factors for metabolic syndrome and NAFLD increase over time in the posttransplant setting[76,77]. Side-effects of immunosuppressive medications and rapid weight gain in the post-transplant period can lead to impaired glucose control,dyslipidemia, development of metabolic syndrome andde novoNAFLD. In fact, it has been reported in 20%-30% of patients following LT for non-NAFLD/NASH etiologies[18,19]. Weight gain is common in patients following LT and 30%-60% of patients become overweight or obese, with a mean weight gain of 2-9 kg usually within the first year after LT. After one year post-LT, weight gain typically slows down[18,78-81]. Obesity appears to be one of the strongest risk factors for the development of NAFLD in the post-transplant period[18,20]. Moreover obese patients after LT have a 2-fold higher risk of mortality compared to normal weight LT recipients[82]. The mechanisms leading to a post-transplant weight gain are driven by a complex interaction of genetic, physiological, behavioral, and environmental factors[83,84]. Dyslipidemia and hypertension occur in 40%-70% of patients, usually related to use of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors and calcineurin inhibitors. Metabolic syndrome has been reported in 40%-50% of patients after LT,both in patients with previous NAFLD as well as other etiologies of chronic liver disease. In a recent report from Mayo Clinic, 84.6% of patients hadde novoallograft steatosis and 15.4% recurrent NAFLD after 2 months post-liver transplant. After 10 years, 48% of liver transplant recipients had evidence of allograft steatosis, including 77.6% of patients transplanted for NASH and 44.7% of individuals transplanted for other indications[20]. Interestingly, in this study allograft steatosis was not associated with worse outcomes regarding graft and patient survival. However, the incidence of cardiovascular events 5 years post-transplant was approximately 40% in patients transplanted for NASH compared to 5%-10% incidence in LT recipients transplanted for non-NASH etiologies, regardless of graft steatosis[20]. This could suggest that impaired metabolic profile before LT could have more significant impact on CV events and outcomes than the post-transplant NAFLD itself. However, the long-term outcomes and consequences of complex interplay between T2DM, obesity, metabolic syndrome, pre- and post-liver transplant NAFLD with CV events require further investigation and explanation.

T2DM TREATMENT IN THE CONTEXT OF NAFLD

Treating type 2 diabetes, although now with available wide range of armamentarium,still remains challenging, especially in the presence of coexisting NAFLD and obesity.Acknowledging the fact that NAFLD and T2DM act synergistically in driving adverse outcomes, in the way that the NAFLD accelerates the development of diabetic chronic micro- and macrovascular complications, while the diabetes increases the likelihood of more severe forms of NAFLD such as steatohepatitis, cirrhosis, and HCC could be an important issue in choosing the treatment modality and pharmacological agent[24,85-89]. Therefore, when taking into account pathophysiology, treating NAFLD/NASH could prevent T2DM development and/or progression, but, also the other way around[90].

As there is no specific pharmacotherapy yet available for treating NAFLD, antidiabetic drugs with pleiotropic effects, targeting multiple metabolic disorders, seem promising. Among them, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) are recognized by American Diabetes Association (ADA) and European Association for Study of Diabetes (EASD)as the best treatment option for patients with T2DM and cardiovascular disease, heart failure and/or chronic kidney disease. These two classes of drugs both exert weight loosing effect, making them especially interesting for patients with associated obesity,and according to results of both randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and open-label studies, offer promising effects in reducing liver fat content[91].

Previously used agents such as metformin and thiazolidinediones (TZDs), affecting insulin resistance, did show benefit on biochemical and metabolic features of NAFLD,but improvement of patients’ histological response or fibrosis was modest and studies were usually short-term therefore lacking information on liver-related long-term outcomes. Moreover, side-effects usually override their wider use in NAFLD patients[92-95]. Especially interesting results came from studies with NASH patients receiving TZDs. Mentioned agents activate the nuclear receptor of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) located in adipose, liver and muscle tissue and exert insulin-sensitizing activity. Additionally, TZDs increase adiponectin,reduce liver fat content and modulate intra hepatic inflammation[94]. Recently published large cohort study in Taiwan using propensity score matching suggested patients with newly diagnosed T2DM receiving either rosiglitazone (not widely used anymore due to associated increased CV risk) or pioglitazone for mean of 3.84 years,compared to newly diagnosed T2DM patients that were non-TZD users, had lower risk of hepatic cirrhosis (incidence rate: 0.77vs1.95 per 1000 person-y)[96].

One of the newer therapeutic modalities that needs to be addressed is certainly pretransplant bariatric surgery in the obese patients with or without diabetes. So far,available data for this particular subset of patients are scarce and data from randomized clinical trials are lacking. However two major points should be considered regarding bariatric procedure in liver transplant (LT) - timing and type of procedure. In a study including 37 patients who underwent LT, and 7 who underwent LT combined with sleeve gastrectomy (SG), majority of patients with LT alone had weight gain to BMI > 35, post-LT diabetes and steatosis with 3 deaths and 3 grafts losses as compared to patients undergoing the combined procedure, who had no graft losses and there were no developed post-LT DM or steatosis, with significant weight loss (mean BMI = 29) after 12 months of follow up. One patient developed a leak from the gastric staple line, and one had excess weight loss. Average time from SG to LT was 17 months[97]. This was confirmed in other study performed in liver and kidney transplant patients who underwent SG 16 months before transplant[98]. There are also some small studies available investigating SG after solid organ transplant showing favorable outcomes regarding weight loss and PTDM incidence[99-101].

In a large cohort study comparing in-hospital mortality and length of stay for patients with no cirrhosis, compensated cirrhosis, and decompensated cirrhosis, who underwent bariatric surgery, patients with decompensated cirrhosis had highest postoperative mortality rate compared to those with compensated and non-cirrhosis patients (16.3%vs0.9% and 0.3%, respectively,P= 0.0002)[102].

Therefore, we can conclude that sleeve gastrectomy is procedure of choice in liver transplant patients with compensated liver cirrhosis since it does not affect absorption compared to other operative modalities and provides beneficial effects in terms of weight reduction, development of PTDM and liver steatosis.

GLP-1RA IN THE TREATMENT OF T2DM

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) are a newer class of antidiabetic medications with a spectrum of beneficial metabolic effects. Besides improving glycaemia by promoting glucose-dependent insulin secretion and inhibition of glucagon secretion, these agents promote weight loss by increasing satiety through central nervous system, delaying gastric emptying and potentially increasing thermogenesis in brown fat tissue. Moreover, GLP-1RAs have proven cardiovascular safety, while some representatives of the class have shown additional cardiovascular benefits/protection in large cardiovascular outcome trials[103-106].

Although receptors for the GLP-1 on the hepatocytes are still a matter of scientific dispute, they appear to have a direct effect on the lipid metabolism of hepatocytes,which leads to reduction of hepatic steatosis and their potential in NAFLD treatment[107-110]. Of additional interest in NAFLD treatment would be their lipidlowering and anti-inflammatory potential[111,112].

GLP-1RA IN THE TREATMENT OF NAFLD

In patients with NAFLD intrahepatic triglyceride accumulates, while hepatic as well as muscle insulin sensitivity declines, which correlates with the IR at the adipose tissue level and its dysfunction. This was a scientific context for assessing the potential of GLP-1Ras in the treatment of NAFLD/NASH from which optimistic results showing reduction in liver enzymes and intrahepatic triglycerides content in patients with T2DM first came[113-116]. It seems that GLP-1RA inhibit dysfunctional endoplasmic reticulum stress response to fatty-acids in hepatocytes and therefore provide protective effects on hepatocytes[110]. In human studies including exenatide (5-10 μg/d) improvements in weight, body mass index, glycemic control, liver enzymes,hsCRP (high-sensitivity C-reactive protein) and adiponectin were seen in patients with ultrasound diagnosed NAFLD treated with GLP-1RA compared to metformin[117], Table 1.

Moreover, smaller studies suggested beneficial effects of exenatide and liraglutide on liver histology[118-120]. Regarding short acting GLP-1RA lixisenatide, studies in obese or overweight T2DM patients reported increase in the proportion of patients achieving normalization of ALT[121], but there is no data on lixisenatide effects on hepatic steatosis or fibrosis.

The first RCT confirming the efficacy of GLP-1RA in the resolution of NASH in patients with biopsy-proven diagnosis was the LEAN trial (Liraglutide Efficacy and Action in NASH) which followed patients for 48 weeks while taking liraglutide 1.8 mg daily[122]. Resolution was achieved in 39% of patients in the active arm compared with 2/22 (9%) participants in the placebo group. It seems that the improvements in liver fat were greater with prolonged duration of liraglutide treatment[119,123-126].

Similar results were suggested in the recently published large scale RCT with semaglutide, a once weekly GLP-1RA including patients with biopsy-proven NASH[127]. There is currently no published data available on oral form of semaglutide regarding the effect on NAFLD/NASH, although it shows superiority over liraglutide in terms of weight loss[128,129].

Another long acting GLP-1RA with a once weekly dosing, dulaglutide, according to results of a Japanese retrospective case series study, and results from the AWARD(Assessment of Weekly Administration of LY2189265 (dulaglutide) in Diabetes)development program seems promising for NASH patients in terms of reduction of liver enzymes and liver stiffness (measured by transient elastography)[130,131]. So far, no data is available for albiglutide (another once weekly administered GLP-1 RA) on NAFLD/NASH features.

SGLT2i IN THE TREATMENT OF T2DM

Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors are widely used oral anti diabetic agents targeting hyperglycemia in an untraditional way, by enhancing glycosuria(with the daily glucose loss ranging between 60 and 80 g). In addition to blood glucose lowering effect, glycosuria also enhances calorie loss (240-320 kcal) and thus gliflozins exert a clinically significant weight-lowering effect. Moreover, their osmotic diuretic and natriuretic effects contribute to plasma volume contraction, and decreasein both systolic and diastolic blood pressures. In the large, recently published cardiovascular outcome trials (EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial with empagliflozin,CANVAS Program with canagliflozin, DECLARE-TIMI 58 with dapagliflozin) SGLT2i proved cardiovascular benefits, primarily seen through the reduction of heart failure risk and studies assessing their renal protective effects are on their way[132-134].

Table 1 Proven and possible effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors in diabetes and metabolism-associated fatty liver disease before and after liver transplantation

SGLT2i IN THE TREATMENT OF NAFLD

SGLT2 inhibitors as a class have shown promising results in open-label studies and RTCs in reducing liver fat[92,135,136]. Majority of mentioned studies used biochemical markers, but some also employed different imaging techniques for assessing fatty liver content and fibrosis, while one small pilot study conducted liver biopsy to determine the hepatic effects of SGLT2 use[137-140]. Gliflozins were effective in reducing liver enzymes in diabetic patients, and more pronounced results were seen in those with accompanying NAFLD[141]. The mechanisms underlying the improvement of NAFLD with SGLT2 inhibitors remain unknown and can only be speculated, Table 1.

It seems that SGLT2 inhibitors, compared to other oral antidiabetic agents with comparable glycemic control, offer more pronounced reductions in serum liver enzymes[142]. Mentioned effect, exceeding glucose-lowering activity, relies on other mechanisms including reduction of body weight and body fat, reduction of serum uric acid, oxidative stress and inflammation which might prove important in NAFLD treatment[143-147].

PTDM IN LT PATIENTS AND THE ROLE OF GLP-1RA

There are no specific guidelines for treatment of PTDM thus general recommendations for diabetes management are followed due to paucity of data regarding usage of antihyperglycemic drugs in transplanted patients.

The main challenge in treatment of post-transplant diabetes is increased cardiovascular risk observed in patients after solid organ transplantation[148]. Due to severe metabolic disturbances caused by weight gain after transplantation and immunosuppressant drugs incidence of cardiovascular events is higher than in nontransplant patients and are the leading cause of mortality[149]. Given that recent data from large cardiovascular outcome trials demonstrated cardiovascular benefits for majority of long acting GLP-1 RA (liraglutide, semaglutide, albiglutide and dulaglutide[103-106]) in terms of reducing 3 point major adverse cardiovascular endpoints comprised of non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke and cardiovascular mortality this therapeutic option has its merits in treatment of PTDM.

Presently, there are no clinical trials published regarding GLP 1RA therapy in PTDM. The only studies available are conducted in case series of patients after kidney and pancreas transplant providing enough scientific rationale for this treatment concept in liver PTDM[150-153]. In a study performed by Haldenet al[150]in patients with and without PTDM after kidney transplant GLP infusion in hyperglycemic clamp led to improvement of insulin and normalization of glucagon concentrations.Furthermore, GLP 1RAs also exhibit resistance against toxicity of immunosuppressive drugsin vitro[154]and seem to prevent steroid diabetes by diminishing glucocorticoidinduced glucose metabolism impairment and beta-cell dysfunction in healthy humans[155].

Since long acting GLP 1RA agonists are eliminated through enzymatic degradation and renaly cleared, drug-drug interactions are avoided which is extremely important in terms of immunosuppressant drug metabolism[156]. However, by delaying gastric emptying, absorption of other drugs could be affected. In a two studies of case series of kidney transplant recipients with PTDM safe co-administration of liraglutide and tacrolimus was reported mitigating, at least partially, concerns regarding absorption interference[152,153].

One of the major downsides of GLP 1RA therapy are gastrointestinal (GI) side effects which could potentiate a GI disturbances caused by immunosuppressant drugs leading to limited usage of GLP 1 RA in spite of their numerous beneficial effects[157],Table 1.

USE OF GLP-1RA IN TREATING NAFLD AND POSTTRANSPLANT NAFLD IN LT PATIENTS

Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of GLP 1 RA seems to be of extreme convenience in LT since none are metabolized by the liver and no dose adjustment is needed[156]. As already mentioned, there is growing body of evidence suggesting beneficial effects of GLP 1RA therapy in patients with NAFLD/NASH affecting not only liver enzymes normalization but also reducing inflammation and progression of fibrosis[122,127,130,131]. There are two different aspects of potential mechanisms of action involving GLP 1RA in post-transplant NAFLD. For one,improvement of metabolic disturbances through induction of weight loss, especially seen during first few weeks after transplantation[158]. Thus, lipogenesis is decreased leading to a reduction in free fatty acid and triglyceride toxic metabolites positively affecting insulin resistance, oxidative stress and inflammation, while increasing insulin secretion initiating changes in gut liver axis which are not completely understood yet[4]. The second relates to direct anti-fibrotic effects independent of metabolic changes recently shown in animal and human studies[159]. Unfortunately there are no clinical studies performed in post-transplant NAFLD/NASH patients,although based on present knowledge this therapeutic approach would be completely justified, Table 1.

PTDM IN LT PATIENTS AND THE ROLE OF SGLT2i

SGLT2 inhibitors have recently been recommended as a treatment of choice for patients with diabetes and high cardiovascular risk, which is also a characteristic of patients with PTDM[160]. The evidence of the use of gliflozins in PTDM in LT patients is scarce, but results from animal studies are promising. Rats with tacrolimus-induced diabetes that received empagliflozin had lower glycemia and increased plasma insulin levels[161]. In a case series of patients with post heart transplant diabetes mellitus,empagliflozin reduced weight, and blood pressure[162]. In a small group of kidney recipients, canagliflozin treatment improved glycemia, reduced weight and blood pressure[163]. Recently published study using empagliflozin in a larger population of PTDM patients after kidney transplantation showed improvement of glycemic control compared to placebo, and a concomitant reduction of body weight[164]. Major potential problem with SGLT2 inhibitors in PTDM might be genitourinary infections,considering concurrent immunosuppressive therapy and glycosuria. Up to date collected data, mainly in the kidney transplant patients with PTDM suggests incidence of the GU infections is not higher than that seen in T2DM patients and resolves with usual antibiotics/antifungal treatment[164], Table 1.

USE OF SGLT2i IN TREATING NAFLD AND POSTTRANSPLANT NAFLD IN LT PATIENTS

Currently, SGLT2 inhibitors have not the indication of improving NAFLD and dedicated research is mandatory in this evolving field. In several RCTs SGLT2 inhibitors have shown positive effects on NAFLD in patients with T2DM, but the exact mechanisms are still speculative, as is their role in treating post-transplant NAFLD in patients with and without diabetes[165]. SGLT2 inhibitors are cleared by the liver, but pharmacokinetic trials involving patients with mild to moderate hepatic impairment demonstrated their safety and no need for dose adjustments in the setting of liver disease[166]. Besides safety, by reducing liver fat content and hepatocyte injury biomarkers which was shown in several gliflozin RCTs they might prove liver protective and improve NAFLD-associated endoplasmatic reticulum stress and mitochondrial function[91]. Additionally, SGLT2 inhibitors are associated with significant weight loss, especially reduction in fat mass and visceral adipose tissue,which makes them interesting agents in treating post-transplant NAFLD in LT patients. Additionally, they attenuate the renin-angiotensin-aldosteron pathway by inhibition of sodium reabsorption which in theory makes the SGLT2 inhibitors ideal for patients with cirrhosis[165], Table 1.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, pharmacological management of PTDM is further complicated given there are no published randomized clinical trials regarding effectiveness and safety of antihyperglycemic agents. Particular characteristics of PTDM include prodiabetogenic potential of immunosuppressant drugs as well as increased cardiovascular risk due to higher incidence of metabolic disturbances present in post-transplant period both of which could be successfully resolved with GLP 1RA and SGLT2i therapy. Further prospective studies including larger number of patients are needed.

Considering that currently NASH is one of the main causes of LT and it is associated with metabolic disorders mainly IR, which is a particular problem in transplanted patients, GLP 1 RA and SGLT2i treatment certainly has the potential to influence precisely this bidirectional relationship between PTDM and preexisting liver disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Hrvojka Dolic for the help with the graphics.

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年21期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年21期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Tailored classification of portal vein thrombosis for liver transplantation: Focus on strategies for portal vein inflow reconstruction

- Alternative uses of lumen apposing metal stents

- lnnate immune recognition and modulation in hepatitis D virus infection

- Use of zebrafish embryos as avatar of patients with pancreatic cancer: A new xenotransplantation model towards personalized medicine

- Gan Shen Fu Fang ameliorates liver fibrosis in vitro and in vivo by inhibiting the inflammatory response and extracellular signalregulated kinase phosphorylation

- Periportal thickening on magnetic resonance imaging for hepatic fibrosis in infantile cholestasis