Regional Effect of APS-sEPS on Intestinal Structure and Mucosal Immunity in Mice

Lei CHENG Qing JIN Rong CHEN Wei ZHANG Niandong YAN Tao XIONG Xiaona ZHAO Liwei GUO

Abstract [Objectives] The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of APS-sEPS (a polysaccharide compound of Astragalus polysaccharides and sulfated Epimedium polysaccharide) on intestinal mucosal immunity and structural morphology.

[Methods] Firstly, the diarrhea model was established using the optimal dose of magnesium sulfate in mice. Then, the diarrhea mice were randomly divided into three groups and given either physiological saline (diarrhea model group) or injected with APS-sEPS or APS. The normal mice were selected as a control group. After administration, the duodenum, jejunum and ileum were processed microtome section, and observed for describing the small intestine morphology, villus height and crypt depth. The tissue homogenates of the duodenum, jejunum and ileum were gathered to detect the changes of sIgA, IL-4 and IL-10.

[Results] The results indicated that APS-sEPS could effectively relieve diarrhea in mice. In the APS-sEPS group, the villus heights of duodenum, jejunum and ileum were increased and the depth of crypt was reduced. The contents of IL-4, IL-10 and sIgA in jejunum and ileum in APS-sEPS group were significantly higher than that in the control group (P<0.05).

[Conclusions] These results indicated that APS-sEPS promoted the recovery of intestinal morphological structure and enhanced the mucosa immunity of the small intestine.

Key words APS-sEPS; mice; Diarrhea; Intestinal mucosa immunity; Morphological structure

Received: August 15, 2020 Accepted: October 23, 2020

Supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (31602099); Key Laboratory of Prevention and Control Agents for Animal Bacteriosis (Ministry of Agriculture) (KLPCAAB -2018-06); the Engineering Research Center of Ecology and Agricultural Use of Wetland, Ministry of Education (KF201913).

Lei CHENG (1995-), male, P. R. China, master, devoted to research about Pharmacology of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

*Corresponding author. E-mail: guolw@yangtzeu.edu.cn; 282308607@qq.com.

The gastrointestinal system represents an enormous surface to the internal world of the gut microbiome and nutrient antigens. Gastrointestinal uptake and process of both beneficial and potentially harmful antigens occur primarily at the intestinal mucosa[1-2]. Mucosal immunity faces the challenge of establishment of the balance between tolerance and immunity, elimination of pathogenic microbes and preservation of the crucial cooperation with normal flora members. Therefore, the intestine provides robust mucosal barrier, composed of physical barrier consisting of specialized epithelial cells, biochemical barrier consisting of mucin glycoproteins, antimicrobial peptides and secretory IgA (sIgA), and the immune barrier consists of organized structures, including Peyers patches (PPs), isolated lymphoid follicles and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs), scattered immune cells throughout the epithelium (intraepithelial lymphocytes, IELs) and lamina propria (LP)[3-5]. Intestinal mucosal immunity is considered as the first line of the body to defense against kinds of harmful substances, and plays a vital role to maintain health by eliminating almost all pathogenic microorganisms. Hence it is an important strategy to reduce the incidence of animal diseases, especially diarrhea, by maintaining the best intestinal immune function of animals under means of drug control.

Numerous studies have shown that traditional Chinese herb medicine used in animal production could improve animals resistance to diseases and enhance immune effect: Diammonium glycyrrhizinate reduced TNF-α and ICAM-1 by inhibiting the NF-κB activation and improve intestinal inflammatory injury in a rat model[6]; and LPS-induced up-regulation of inflammatory mediators, including interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6 and IL-8, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), inducible nitric oxide synthases (iNOS) were reduced after being pre-treated with wogonin in Caco-2 cells[7]. Furthermore, the ingredient glycyrrhetinic acid also exerted protective effects on LPS stressed intestinal epithelial cells injury and expression of the epithelial tight junction molecules[8]. The mechanisms might be related to intestinal environment improvement, immune modulation, and regulation of inflammatory pathways or cytokines[9]. Ginseng polysaccharide and Polyporus umbellatus polysaccharide increased the secretion of IFN-γ and decreased TNF-α in the intestinal mucosa of autoimmune arthritis rats[10]. Polysaccharides, a class of the main effective ingredients in herb medicine, have been suggested to influence the intestinal mucosal barrier function via promoting the development and functional maturation of epithelial cells and mucosal immune cells as well as the secretion of mucus that is produced by goblet cells, sIgA and cytokines[11-14]. Our previous studies also proved that the immune enhancement of compound CHMIs was stronger than the single and the corresponding compound CHMs[15]. Consecutive research showed that compound astragalus polysaccharide and sulfated epimedium polysaccharide injection (APS-sEPS) could significantly promote lymphocyte proliferation and enhance serum antibody titer in chickens, and resist the immunosuppression induced by cyclophosphamide[16-17]. Furthermore, APS-sEPS oral liquid was proved to promote the secretion of sIgA in trachea, duodenum and jejunum, the level of IL-17 in duodenum and jejunum, the production of IgA+ cells in the tonsil of jejunum and cecum, and the number of lymphoid cells in jejunum mucosa. All those studies manifested that APS-sEPS might have an improved effect on the mucosal immune function[18]. However, there are few reports on the effects of APS-sEPS on intestinal mucosal repair. Therefore, the present study was conducted to verify the effects of the compound Astragalus polysaccharides and sulfated Epimedium polysaccharide on intestinal structure and immunity of diarrhea mice.

Materials and Methods

ICR mice (No. SYXK 2019-0013), 8-week-old (weight 20 g±0.2 g), were purchased from the animal experiment center of Wuhan University (Hubei, China). Animals were adapted to the new rodent facility before experiment. They were housed under a specific pathogen-free environment with a 12 h light-dark cycle at (25±2) ℃ and (50%±5%) relative humidity and had free access to standard laboratory diet and water during experimental period. All animal handling procedures strictly complied with the P.R. China Legislation on the Use and Care of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Animal Care Review Committee, Yangtze University. Adapted for 2 d to rule out stress diarrhea, fifty test mice randomly were divided into five groups for measuring the laxative dose of magnesium sulfate. After fasting for 24 h, mice in different groups were administered with 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, and 0.4 ml of 35% magnesium sulfate aqueous solution, respectively but in control group, with 0.4 ml of normal saline, the administration was taken every 24 h for 2 d. Then we observed which group was diarrhea, and determined the optimal dose of magnesium sulfate-induced diarrhea in mice.

The experiment mice were allowed free access to water and experimental diets. The mice were fasted 12 h before the test. Forty mice were randomly divided into 4 groups: APS-sEPS group, drug control group (APS group), diarrhea model group and blank control group. Except the mice in blank group, other thirty mice were intragastrically administered with 0.4 ml of 35% magnesium sulfate aqueous solution to cause diarrhea. After 2 d, the mice were given 20% APS-sEPS solution, 20% APS solution in APS-sEPS group and drug control group, respectively, and given the normal saline in blank group and the diarrhea model group.

Sample collection

The diarrhea of the mice was observed, and the anatomy was operated after 24 h ending the administration. Duodenum, jejunum and ileum were collected for observing the intestinal lesions, and then 2 cm area with significant lesions was selected for making histologic section. Other fragments of duodenum, jejunum, ileum were grinded, centrifuged for 20 min with 12 000 r/min. The supernatant was taken for testing the variation of various cytokines according to the ELISA detection kit manual operation.

Histomorphometry

Tissue slices were prepared by hematoxylin and eosin straining according to the method of Luna[19]. In brief, intestinal segments were processed by being fixed, dehydrated, paraffined, embedded, sliced and stained. Five observations were made on each slice and in each observation two villi that were well-stretched and parallel were measured quantitatively for analysis of villus height and crypt depth. According to the results, villus height: crypt depth ratio (VCR) was calculated. Villus height was measured from the tip of the villus to the villus-crypt junction; and crypt depth was defined as the depth of the invagination between adjacent villi. Villus height and crypt depth were measured at 100× magnification using Image-Pro Plus software (Image-Pro Plus 6.0, Media Cybernetics, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 22.0, Chicago, IL). Means and standard deviation of the means were reported for the 4 experimental groups (mean±SD). As data were normally distributed, statistical analyses were conducted by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Duncan multiple comparisons tests. The variability of the data was expressed as the standard error and a probability level of P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results and Analysis

Optimal induced-diarrhea dose for magnesium sulfate

In order to ascertain the optimal induced-diarrhea dose of magnesium sulfate, we investigated the clinical diarrhea manifestation in different doses. The result showed that diarrhea did not occur in 0.1, 0.2, and 0.3 ml of 35% magnesium sulfate aqueous solution, but after administered 0.4 ml of 35% magnesium sulfate aqueous solution, the mice had symptoms of diarrhea 50 min later. Therefore, the optimal induced-diarrhea dose of magnesium sulfate in mice was selected to be 0.4 ml of 35% magnesium sulfate aqueous solution.

Intestinal histopathological changes

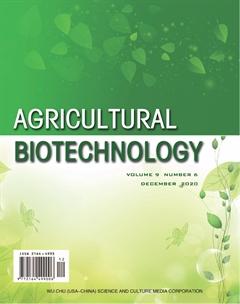

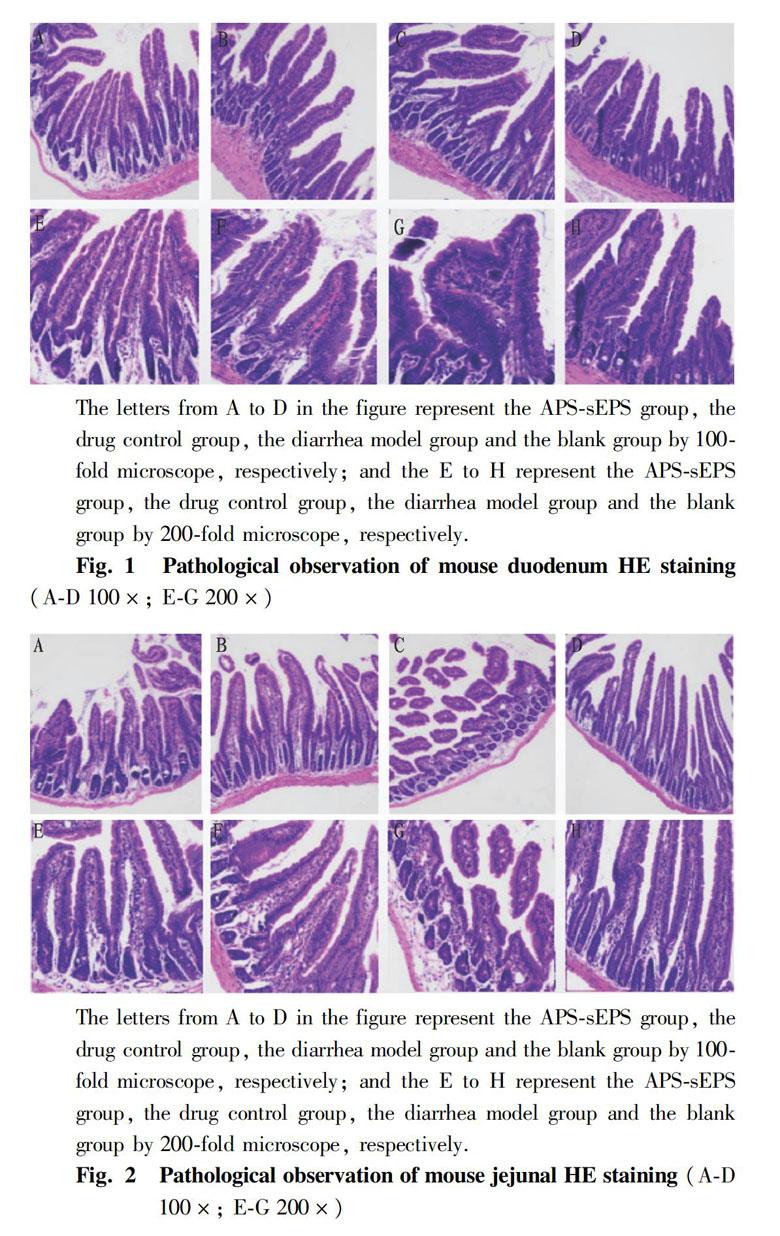

In order to observe the intestinal histopathological changes, all the mice were killed by cervical dislocation, and the tissue sections of the duodenum, jejunum and ileum of each group of mice were obtained to process microtome section. The results viewed under microscope were showed in the Fig. 1-Fig. 3 below.

From Fig.1A, the result showed that the duodenal villi of the mice in the APS-sEPS group recovered to the optimal state, the villi were arranged most closely, and the structure of the intestinal mucosa was relatively complete. In the APS group, the duodenal villi were restored in Fig.1B, but the villus arrangement was sparse. Fig.1F shows that the length of the villi was shorter than that of the APS-sEPS group. In the diarrhea model group, the duodenal villi had been damaged. The intestinal villus rupture and the arrangement are not neat in Fig. 1C. In the blank control group, the duodenal villi were relatively intact and showed finger-like protrusions.

It can be seen from Fig. 2 that the length of jejunal intestine villi in the APS-sEPS group was basically the same, and the arrangement was dense; and the length of jejunum in the APS group was larger than that in the model group, and the intestinal villi were thick and complete. In the diarrhea model group, the jejunal villi were severely damaged, and the villi broke and even fell off in Fig. 2C. The epithelial cells were swollen in Fig. 2G. The blank control group had the best intestine villi, and the villi were intact, dense and slender, and arranged closely.

It was shown that the ilea in APS-sEPS and APS group were densely arranged; the ilea in diarrhea model group had slight damage, which showed some of the villus rupture and detachment; and the ileum intestine was intact in the blank control group.

Changes of villus length, crypt depth and the villus height to crypt depth ratio.

In order to evaluate the repairing effects of APS-sEPS on damage intestine, the changes of intestinal villus length, crypt depth and the villus height to crypt depth ratio were investigated in different groups. The results are shown in Fig. 4, Fig. 5 and Table 1.

The results in Fig. 4 show the changes in intestinal villus length in different groups. Compared with the blank control group, the intestinal tract of the diarrhea model group was shorter than the normal control group. The intestinal villi of duodenum and jejunum in the APS-sEPS group were significantly longer than those in the diarrhea model group (P<0.05). In the APS group, the intestinal villi of each intestinal segment were longer than those in the diarrhea model group, but only in the jejunum segment, the intestinal villi were significantly longer than those in the diarrhea model group (P<0.05).

The results in Fig. 5 showed that the crypt depths of duodenum and jejunum in the diarrhea model group were significantly deeper than those of the blank control group (P<0.05), but there was no significant difference in the crypt depth of ileum between the diarrhea model group and the blank control group. The crypt depths of duodenum and jejunum in the APS group were significantly lower than those of the diarrhea model group (P<0.05), and the crypt depth of duodenum was significantly lower than that of the APS-sEPS group (P<0.05). The crypt depths of duodenum and jejunum in the APS-sEPS group were lower than those of the diarrhea model group (P>0.05), but there were no significant differences.

In order to understand the effect of polysaccharide on the repair of intestinal structure, we investigated whether APS-sEPS had a repairing effect on the intestinal tissue damaged by diarrhea in mice. The result showed that the V/C values of the intestines in the APS-sEPS group were higher than those in the diarrhea model group, but only the V/C value of the jejunum was significantly higher (P<0.05). The V/C values of the intestines in the APS group were higher than those in the diarrhea model group, but lower than those in the APS-sEPS group. Only the V/C value of the jejunum in the APS-sEPS group was significantly higher than that in the APS group (P<0.05).

The above results showed that APS-sEPS could promote the repair of duodenum, jejunum and ileum of diarrhea mice, and the effect in jejunum was the best.

Changes of intestinal IL-4, IL-10 and sIgA secretion in diarrhea mice

In order to prove polysaccharides enhance intestinal mucosal immunity in animals, we investigated whether APS-sEPS promotes the secretion of IL-4, IL-10 and sIgA in the intestine of diarrhea mice. The result in Fig 6 show the variation of IL-4, IL-10 and sIgA in diarrhea mice intestines.

In the duodenum segment of diarrhea mice, there were no significant differences in the contents of IL-4, IL-10 and sIgA (P>0.05).

In the jejunum segment, the contents of IL-4 and sIgA in the APS-sEPS group and APS group were significantly higher than those in the diarrhea model group (P<0.05). There was no significant difference between the APS-sEPS group and APS group (P>0.05). The contents of IL-4 and sIgA in the ilea in the APS-sEPS group and APS group were significantly higher than those in the diarrhea model group (P<0.05), and the contents of IL-4 and sIgA in the APS-sEPS group were higher than those in the APS group (P>0.05), but there was no significant difference between the APS-sEPS group and APS group.

In the jejunum and ileum segment, the content of IL-10 in the APS-sEPS group and APS group was significantly higher than that in diarrhea model group (P<0.05). And the content of IL-10 in the APS-sEPS group was significantly higher than that in the APS group (P<0.05). The content of IL-10 in the APS-sEPS group was higher than that in the APS group (P>0.05), but there was no significant difference between the APS-sEPS group and APS group.

The above results showed that the APS-sEPS and APS both promoted the secretion of IL-4, IL-10 and sIgA in jejunum and ileum of diarrhea mice.

Discussion

Mucosal homeostasis at the gastrointestinal tract requires a delicate co-existence of gut microbiota with the gut-associated mucosal immune system, an interaction that is constantly challenged by environmental factors[20]. Hence, mucosal “health” is depended on an intact genetic structure, preserved by the integrity of the epithelial barrier, and fine-tuned by immunoregulatory responses[1]. Failure of one or more of these balancing elements leads to breakdown of homeostasis and predominance of immunological dysfunction circuits.

Intestinal morphology involving villus height, crypt depth as well as VCR could be served as criteria reflecting intestinal damage conditions[21]. The mucosal surface barrier comprises several types of IECs, which are functionally and biologically categorized as either absorptive (columnar epithelial cells) or secretory (Paneth, goblet, enteroendocrine, and tuft cells)[22-23]. Data from in vivo analyses coupled with recent progress in in vitro organoid (so-called minigut) systems have revealed that all of the component populations in IECs are derived from a single stem cell population that resides at the base of the intestinal crypt[24]. The reduction of intestine length and weight might indicate intestine dysfunction. A shortening of the villi and deeper crypts may lead to poor nutrient absorption, increased secretion in the gastrointestinal tract, and lower performance[25]. In contrast, increased villus height and villus height:crypt depth ratio are directly correlated with increased epithelial cell turnover, and longer villi are associated with activated cell mitosis[26-27]. The crypts and villi in the intestine, constituted by intestinal epithelial cells structurally, determine the absorption area of the small intestine, the absorption of nutrients and the growth of the animals[28]. As the indices of intestinal physiological status, the intestinal growth parameters, such as length and weight, could be altered by the oral administration of some natural polysaccharides to improve the intestinal health[29-30]. In China, many studies also had demonstrated that Chinese herbal medicines and ingredients (CHMIs), such as polysaccharides, flavones and saponin, possessed antiviral activity[31]. These findings strongly suggested that CHMIs could protect intestinal morphology against injury induced by challenge. Our results also revealed that the polysaccharide compounds of APS-sEPS and APS both had repaired the injury of duodenum, jejunum and ileum tissues of the diarrhea mice. And APS-sEPS and APS could significantly recover the length of intestinal villus, and reduce the depth of crypt in duodenum, jejunum and ileum. Hans study reported that oral pre-treatment with ASPS could improve intestinal integrity of mice under inflammation conditions, and ameliorate LPS-induced intestinal morphological deterioration, proven by improved villus height and villus height: crypt depth ratio[32]. The supplementation of prescription of 0.1% CMH to the diet for weanling pigs enhanced their immune activity, decreased Escherichia coli counts in colon and increased the villous height and nutrient digestibility compared with the control group(CT)[33].

To fine-tune immunoregulatory responses is critically dependent on key cellular and/or soluble mediators, most prominent among which are cytokines and their receptors. IL-4, IL-10 and sIgA play an important role in animal immunity. IL-4 is a proinflammatory factor, which can promote the proliferation of B cells, the expression of IgE and the proliferation of mast cells. IL-10 is an anti-inflammatory factor, which can inhibit Th1 cells secreting cytokines, and promote B cells to proliferate and secrete antibodies. IL-4 and IL-10 can make the transformation of B cells, which promotes the secretion of sIgA[34]. As the main substance of intestinal immunity, sIgA plays an important role in resisting the invasion of foreign pathogens. Studies have shown that sIgA can promote the formation of intestinal biofilm[35]. At present, most studies focus on the effects of polysaccharides on mucosal immunity. Polysaccharides can promote the proliferation of intestinal epithelial cells and activate intestinal immune cells[36]. For example, the polysaccharide from Radix pseudostellariae stem and leaves could increase the content of IL-2, IL-4 and sIgA in intestinal tract, promote the proliferation of intestinal secretory cells, and improve the immunity[37]. Coix alkali-extract polysaccharides induced the secretion of NO, TNF-α and IL-6 of RAW264.7 murine macrophages, and increased the fecal butyric acid concentration and lactic acid bacteria on adlay-fed rats, which had been regarded as a healthy metabolite for its role in nourishing the colonic mucosa, regulating epithelial and immune cell growth and apoptosis, exerting an anti-inflammatory effect[38]. The present results also showed that both APS-sEPS and APS increased the content of IL-4 and IL-10 in jejunum and ileum of diarrhea mice, and the effect of APS-sEPS was slightly stronger than that of APS. Both APS-sEPS and APS increased the content of sIgA in duodenum and jejunum. It was suggested that APS-sEPS could promote to increase the secretion of IL-4, IL-10 and sIgA in intestinal mucosa, which would enhance the intestinal mucosal immunity of animals.

Conclusions

This study found that APS-sEPS, a traditional Chinese medicine preparation, could repair intestinal tissue damaged by diarrhea in mice, increase the heights of duodenum, jejunum and ileum villi in different degrees, reduce the depth of crypt, and increase the ratio of villus height to crypt depth, indicating that APS-sEPS can improve the mucosal morphology of small intestine in diarrhea mice. APS-sEPS has the potential of immunological modulation on intestinal mucosa of animals.

References

[1] MADACH K, KRISTOF K, TULASSAY E. Mucosal immunity and the intestinal microbiome in the development of critical illness[J]. ISRN Immunology, 2011, (12): 545729. http://dx.doi.org/10.5402/2011/545729

[2]YOSUKE K, KIYONO H. Mucosal ecological network of epithelium and immune cells for gut homeostasis and tissue healing[J]. Annual Review Immunology, 2017(35): 119-147.

[3] PEREZ-LOPEZ A, BEHNSEN J, NUCCIO SP, et al. Mucosal immunity to pathogenic intestinal bacteria[J]. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2016(16): 135-148.

[4] PETERSON LW, ARTIS D. Intestinal epithelial cells: Regulators of barrier function and immune homeostasis[J]. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2014(14): 141-153.

[5] PFEIFFER JK, VIRGIN HW. Transkingdom control of viral infection and immunity in the mammalian intestine[J]. Science, 2016(351): 207-310.

[6] YUAN H, JI WS, WU KX, et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of diammonium glycyrrhizinate in a rat model of ulcerative colitis[J]. World Journal of Gastroenterollgy, 2006(12): 4578-4581.

[7] WANG W, XIA T, YU X. Wogonin suppresses inflammatory response and maintains intestinal barrier function via TLR4-MyD88-TAK1-mediated NF-κB pathway in vitro[J]. Inflammation Research, 2015(64): 423-431.

[8] HU L N, FANG X Y, LIU H L. Protective effects of 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid on LPS-induced injury in intestinal epithelial cells[J]. Chinese Journal of Natural Medicine, 2013(11): 24-29.

[9] WANG C, TANG X, ZHANG L. Huangqin-Tang and ingredients in modulating the pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis[J]. Evidence-Based Complementray and Alternative Medicine. 2017, 7016468. doi: 10.1155/2017/7016468.

[10] ZHANG WD, LV C, ZHAO HY, et al. Effect of ginseng polysaccharide and Polyporus umbellatus polysaccharide on function of mucosal immune cell in CIA rats[J]. Chinese Journal of Cellular Molecular Immunology, 2007(23): 867-870.

[11] ZUO T, CAO L, XUE C, et al. Dietary squid ink polysaccharide induces goblet cells to protect small intestine from chemotherapy induced injury[J]. Food & Function, 2015(6): 981-986.

[12] MEDRANO M, RACEDO SM, ROLNY IS, et al. Oral administration of kefiran induces changes in the balance of immune cells in a murine model[J]. Journal of Agricultural & Food Chemistry, 2011(59): 5299-5304.

[13] JIN M, ZHU Y, SHAO D, et al. Effects of polysaccharide from mycelia of Ganoderma lucidum on intestinal barrier functions of rats[J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2017(94): 1-9.

[14] XU X, YANG J, LUO Z, et al. Lentinula edodes-derived polysaccharide enhances systemic and mucosal immunity by spatial modulation of intestinal gene expression in mice[J]. Food & Function, 2015(6): 2068-2080.

[15] SUN JL, HU YL, WANG DY, et al. Immunologic enhancement of compound Chinese herbal medicinal ingredients and their efficacy comparison with compound Chinese herbal medicines[J].Vaccine, 2006(24): 2343-2348.

[16] GUO LW, WANG DY, HU YL, et al. Adjuvanticity of compound polysaccharides on chickens against Newcastle disease and avian influenza vaccine[J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2012(50): 512-517.

[17] GUO LW, LIU JG, HU YL, et al. Astragalus polysaccharide and sulfated Epimedium polysaccharide can synergistically resist the immunosuppression induced by cyclophosphamide in chickens[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2012(90): 1055-1060.

[18] Chen XY, Studies on Chinese berbal medicinal polysaccharide immunopotentiator AEO and its mechanism, a Dissertation Submitted to Nanjing Agricultual University, China, 2014.

[19] LUNA LG. Manual of histologic staining methods of the armed forces institute of pathology. 3th ed.[M] New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company Press, 1968.

[20] VALATASL V, KOLIOS G, BAMIAS G. TL1A (TNFSF15) and DR3 (TNFRSF25): A co-stimulatory system of cytokines with diverse functions in gut mucosal immunity[J]. Frontiers in Immunology, 2019(10): 1-14.

[21] EWASCHUK J, ENDERSBY R, THIEL D, et al. Probiotic bacteria prevent hepatic damage and maintain colonic barrier function in a mouse model of sepsis[J]. Hepatology, 2007(46): 841-850.

[22] KARAM SM. Lineage commitment and maturation of epithelial cells in the gut[J]. Frontiers in Bioscience, 1999(4): 286-298.

[23] JENSEN J, PEDERSEN EE, GALANTE P, et al. Control of endodermal endocrine development by Hes-1[J]. Nature Genetics, 2000(24): 36-44.

[24] KOO BK, CLEVERS H. Stem cells marked by the R-spondin receptor LGR5[J]. Gastroenterology, 2014(147): 289-302.

[25] XU ZR, HU CH, XIA MS, et al. Effects of dietary fructooligosaccharide on digestive enzyme activities, intestinal microflora and morphology of male broilers[J]. Poultry Science, 2003(82): 1030-1036.

[26] FAN Y, CROOM J, CHRISTENSEN V, et al. Jejunal glucose uptake and oxygen consumption in turkey poults selected for rapid growth[J]. Poultry Science, 1997(76): 1738-1745.

[27] SAMANYA M, YAMAUCHI K. Histological alterations of intestinal villi in chickens fed dried Bacillus subtilis var. natto[J]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology, 2002(133): 95-104.

[28] GREIG CJ, COWLES RA. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors participate in small intestinal mucosal homeostasis[J]. Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 2017(52): 1031-1034.

[29] MA G, KIMATU BM, ZHAO L, et al. In vivo fermentation of a Pleurotus eryngii polysaccharide and its effects on fecal microbiota composition and immune response[J]. Food & Function, 2017(8): 1810-1821.

[30] XIE SZ, LIU B, ZHANG DD, et al. Intestinal immunomodulating activity and structural characterization of a new polysaccharide from stems of Dendrobium officinale[J]. Food & Function, 2016(7): 2789-2799.

[31] LI T, PENG T. Traditional Chinese herbal medicine as a source of molecules with Antiviral activity[J]. Antiviral Research, 2013(97): 1-9.

[32] HAN J, LIU L, YU N, et al. Polysaccharides from Acanthopanax senticosus enhances intestinal integrity through inhibiting TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathways in lipopolysaccharide-challenged mice[J]. Animal Science Journal, 2016(87): 1011-1018.

[33] HUANG CW, LEE TT, SHIH YC, et al. Effects of dietary supplementation of Chinese medicinal herbs on polymorphonuclear neutrophil immune activity and small intestinal morphology in weanling pigs[J]. Journal of Animal Physiollgy and Animal Nutrition, 2012(96): 285-294.

[34] MOWAT AM. The regulation of immune responses to dietary protein antigens[J]. Immunology Today, 1987(8): 93-98.

[35] HOWARD LW. Oral telerance: Immune mechanisms and treatment autoimmune dieseases[J]. Immunology Today, 1997(18): 335-343.

[36] MASLOWSKI KM, MACKAY CR. Diet, gut microbiota and immune responses[J]. Nature Immunology, 2011(12): 5-9.

[37] CHEN LF, CAI XB, TAN XZ, et al. Effects of Radix Pseudostellariae stem and leaf polysaccharide on intestinal immune function, intestinal mucosal morphology and cecum contents flora of weaned piglets[J]. Chinese Journal of Animal Nutrition, 2017(29): 1012-1020.

[38] YIN HM, WANG SN, NIE SP, et al. Coix polysaccharides: Gut microbiota regulation and immunomodulatory[J]. Bioactive Carbohydrates & Dietary Fibre, 2018(16): 53-61.

Editor: Yingzhi GUANG Proofreader: Xinxiu ZHU

- 农业生物技术(英文版)的其它文章

- Effects of LPS on the Gene Expression of NMB and Its Receptor in the Hypothalamic-pituitary-testicul

- Comparative Nutritional Analysis on Fish Meal and Meat and Bone Meal of Harmless Treatment of Dead Pig Carcass

- A Monophyletic Status of Axis Genus in Subfamily Cervinae Supported by the Complete Mitochondrial Genome of Chinese Hog Deer (Axis porcinus)

- Prevention and Control Measures of the Occurrence of Ceracris kiangsu Tsai in Sugarcane Areas of Yunnan Province

- Study on the Accuracy of Different CASA Systems in the Quality Detection of Fresh Boar Semen

- Evaluation and Selection of Appropriate Tobacco Varieties for Badong Hubei Province