柠檬酸铁胺对SH-SY5Y细胞中葡萄糖脑苷脂酶活性及其蛋白表达的影响

陈兵兵 宓晓晴 李云 谢俊霞 宋宁

[摘要] 目的 探究柠檬酸铁胺(FAC)对SH-SY5Y多巴胺能细胞系葡萄糖脑苷脂酶(GCase)活性及其蛋白表达的影响。方法 用FAC、GCase活性抑制剂环己烯四醇环氧化物(CBE)分别或共同处理细胞48 h,应用荧光法检测GCase活性,免疫印迹法检测GCase蛋白表达。结果 FAC和CBE两种因素共处理,对GCase活性及其蛋白表达的影响不存在交互作用(P>0.05)。FAC处理SH-SY5Y细胞后,GCase活性降低,蛋白表达升高,与对照组比较差异具有统计学意义(F=8.191、4.934,P<0.05);CBE处理SH-SY5Y细胞后,GCase活性降低,蛋白表达升高,与对照组比较差异具有统计学意义(F=14.605、4.182,P<0.05)。结论 高铁可降低SH-SY5Y细胞中GCase的活性,升高蛋白的表达。

[关键词] 铁;柠檬酸盐类;葡糖苷酰鞘氨醇酶;SH-SY5Y细胞

[中图分类号] R338.1;R345.62 [文献标志码] A [文章编号] 2096-5532(2020)02-0143-04

doi:10.11712/jms.2096-5532.2020.56.058 [开放科学(资源服务)标识码(OSID)]

[网络出版] http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/37.1517.R.20200407.0930.004.html;2020-04-07 14:57

[ABSTRACT] Objective To explore the effect of ferric ammonium citrate (FAC) on glucocerebrosidase (GCase) activity and expression in SH-SY5Y dopaminergic cells. Methods SH-SY5Y dopaminergic cells were treated with FAC and the GCase inhibitor conduritol B epoxide (CBE), alone or in combination, for 48 h. Fluorometric assay was used to determine the GCase acti-vity. Western blotting was performed to determine the expression level of GCase. Results When FAC and CBE were used in combination to treat the SH-SY5Y cells, there was no interaction between them with regard to the effect on GCase activity and expression (P>0.05). SH-SY5Y cells treated with FAC alone showed a significantly decreased GCase activity and a significantly increased GCase expression level compared with the control group (F=8.191,4.934,P<0.05); SH-SY5Y cells treated with CBE alone also showed a significantly decreased GCase activity and a significantly increased GCase expression level compared with the control group (F=14.605,4.182,P<0.05). Conclusion High level of iron can decrease the activity and increase the expression level of GCase in SH-SY5Y cells.

[KEY WORDS] iron; citrates; glucosylceramidase; SH-SY5Y cells

近年来遗传基因的发现为家族性和散发性帕金森病(PD)的发病机制提供新见解,有5%~10%的PD病例是遗传因素所致[1-2]。临床研究发现,PD病人中编码葡萄糖脑苷酯酶(GCase)的基因GBA突变率达20%,因此GBA突變是目前已知的PD和相关突触核蛋白病发展的最常见的遗传危险因素[3-5]。GCase是一种具有497个氨基酸的膜相关性蛋白,该蛋白在内质网中合成和经糖基化修饰后,被溶酶体膜整合蛋白-2转运至溶酶体中,发挥生物学功能[6]。GCase活性的降低可以导致葡萄糖神经酰胺的聚积,进而导致戈谢病的发生[7]。在PD中,GBA突变降低了GCase的活性,导致α-突触核蛋白聚集,而聚集的α-突触核蛋白又进一步促进了GCase活性的降低,形成恶性循环,造成多巴胺能神经元的死亡,因此GCase的活性与PD的发病进程密切相关[8-12]。铁是PD发病的重要因素之一[13],铁可以诱导氧化应激和铁死亡等[14-16],从而造成多巴胺能神经元的选择性损伤。然而,目前关于铁对GCase活性及其蛋白表达的影响尚未见报道。因此,本研究应用柠檬酸铁铵(FAC)制备SH-SY5Y多巴胺能细胞系的高铁模型,并使用GCase的不可逆竞争性抑制剂环己烯四醇环氧化物(CBE)作为对照药,探讨铁对GCase活性及其蛋白表达的影响。现将结果报告如下。

1 材料与方法

1.1 实验材料

SH-SY5Y细胞系由中国科学院上海细胞库提供,DMEM高糖基础培养液、胎牛血清(FBS)购自以色列BI公司,4-甲基伞形酮-β-葡萄糖苷(4-MU-β-GLC)、CBE、FAC和GCase一抗购自美国Sigma公司,β-actin抗体、HRP-IgG标记的二抗购自北京博奥森公司,ECL发光液为Millipore公司产品,其他试剂均为国产分析纯。

1.2 SH-SY5Y细胞的培养

实验前将实验器具高压灭菌。从液氮中取出冻存的SH-SY5Y细胞转移到37 ℃水浴中迅速(30 s内)解冻,充分摇匀后置于离心机中,以1 000 r/min离心5 min,弃去上清,加入完全培养液吹打均匀后接种到25 cm2细胞培养瓶中,光镜下观察细胞是否贴壁,然后置于培养箱中(37 ℃、含体积分数0.05 CO2)培养,每隔2 d传代1次。

1.3 实验分组及处理

将SH-SY5Y细胞分为对照组(A组)、FAC处理组(B组)、CBE处理组(C组)、FAC和CBE共处理组(D组)。将SH-SY5Y细胞以2×104/cm2的密度接种于6孔板中,每孔加入1.5 mL的细胞混悬液。当细胞达到50%~70%融合时,对照组加入新鲜无血清的培养液;FAC处理组加入100 μmol/L的FAC;CBE处理组则加入100 μmol/L的CBE;FAC和CBE共处理组先加入100 μmol/L的CBE预孵育30 min,再加入100 μmol/L的FAC。上述各组药物处理时间均为48 h。

1.4 GCase酶活性的测定

药物处理48 h后每孔加入100 μL的磷酸盐缓冲液,于冰上静置30 min后用刮板刮下细胞并在细胞破碎仪中破碎,破碎强度为30%;在4 ℃下以12 000 r/min离心10 min;取2.5 μL的上清,加入5 mmol/L的4-MU-β-GLC 12.5 μL,37 ℃孵育30 min后,加入1 mol/L的甘氨酸缓冲液(pH值=10)终止反应。在酶标仪上设定激发光波长EX=360 nm、发射光波长Em=460 nm,检测产物4-甲基伞形酮的含量,以相对荧光单位(RFU)表示,并应用BCA蛋白定量试剂盒检测提取样品的蛋白浓度(RFU/μg总蛋白)。

1.5 免疫印迹法检测GCase蛋白表达

药物处理48 h后提取蛋白,用BCA蛋白定量试剂盒检测提取蛋白的浓度,以每孔总蛋白量为20 μg计算蛋白上样量,加入Loading Buffer,95 ℃煮5 min。经120 g/L的SDS-PAGE凝胶电泳后湿转到0.45 μm 的PVDF膜上,室温下用100 g/L的脱脂奶粉溶液封闭2 h,再分别加入GCase(1∶1 000)和β-actin(1∶10 000)一抗于4 ℃摇床过夜。第2天用山羊抗兔的HRP-IgG(1∶10 000)孵育1 h后以TBST溶液洗3次,每次10 min,ECL发光液显影后用Image J统计结果。

1.6 统计学处理

应用SPSS 22.0软件进行统计分析,实验结果以±s表示,针对FAC和CBE两种处理因素,采用析因设计的方差分析进行处理,以P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结 果

2.1 FAC对GCase活性的影响

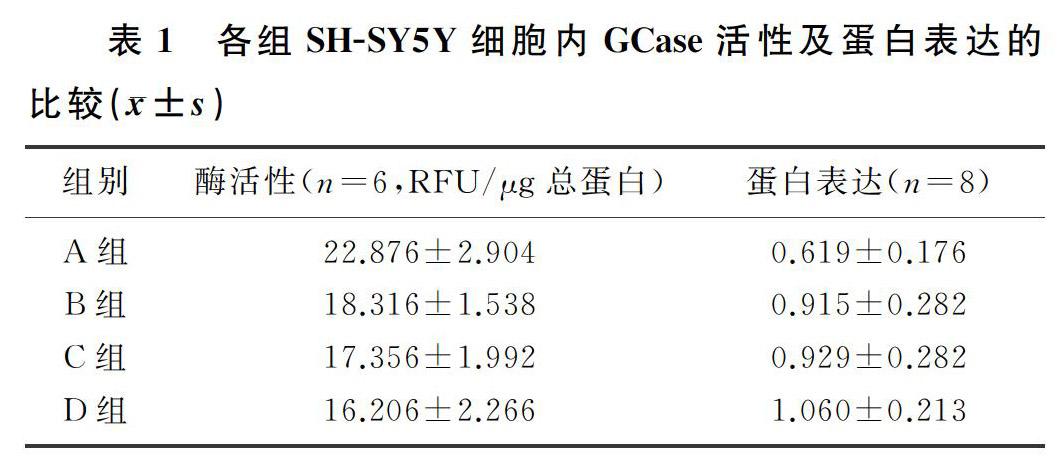

析因设计方差分析显示,FAC和CBE这两种因素对GCase活性的影响不存在交互作用(P>0.05),因此进一步分析FAC、CBE主效应的结果是否具有统计学意义。100 μmol/L FAC处理SH-SY5Y细胞48 h后,FAC处理组酶活性较对照组有明显的下降,差异有统计学意义(F=8.191,P<0.05);在CBE处理SH-SY5Y细胞48 h后,CBE处理组酶活性也较对照组明显下降,差异有统计学意义(F=14.605,P<0.05)。见表1。

2.2 FAC对GCase蛋白表达的影响

析因设计方差分析显示,FAC和CBE两种因素不存在交互作用(P>0.05),因此进一步分析FAC、CBE主效应是否有统计学意义。100 μmol/L FAC处理SH-SY5Y细胞48 h后,FAC处理组蛋白表达较对照组明显上调,差异有统计学意义(F=4.934,P<0.05);在100 μmol/L CBE处理SH-SY5Y细胞48 h后,CBE处理组与对照组比较蛋白表达明显上调,差异有统计学意义(F=4.182,P<0.05)。见表1。

3 讨 论

PD的发病机制迄今未明,研究表明遗传因素、环境因素和老化因素均可参与PD中多巴胺能神经元的变性死亡过程[17-19]。据文献报道,在PD病人的黑质(SN)中铁的总量随疾病严重程度的增加而增加[20-23],这些过量的不稳定性铁可通过Fenton反应催化产生具有高细胞毒性的羟自由基[14,22-25],导致细胞死亡,从而造成疾病的发生。在GBA突变的PD病人的小脑、壳核、杏仁核、SN中GCase活性降低,其中以SN最明显。同时,在非GBA突变的散发性PD病人小脑和SN中GCase活性也明显下降[26-27]。在6-羟基多巴胺制备的PD大鼠模型中,检测到SN和纹状体的GCase活性下降[28]。

本实验用100 μmol/L FAC、100 μmol/L CBE处理SH-SY5Y多巴胺能神经元细胞系,研究铁对GCase活性及蛋白表达的影响。文献报道,溶酶体内的酶都是水解酶,而且一般最适pH值为5.0,所以都是酸性水解酶[29]。有研究表明,在铁负载的细胞中,溶酶体pH值从5.0增加到5.7,高铁破坏了细胞内溶酶体的酸性环境[30]。本研究结果显示,在FAC处理SH-SY5Y细胞48 h后,GCase的活性明显降低,提示细胞内的高铁环境破坏了溶酶体内的酸性环境,从而使GCase的活性降低。而GCase活性的降低可能代偿性地引起了GCase蛋白表达的增加。有关文献报道,神经元中加入野生型或者A53T突变的α-突触核蛋白在降低溶酶体中GCase活性的同时增加了GCase的蛋白表达,α-突触核蛋白可抑制GCase在细胞内的运输[31]。既往有研究表明,在SH-SY5Y细胞中,FAC可以诱导α-突触核蛋白表达升高[32-33],CBE也可以诱导α-突触核蛋白表达升高[34-36]。本实验加入铁后细胞的GCase蛋白表达明显升高,推测可能是细胞内高铁环境诱导了α-突触核蛋白表达升高,升高的α-突触核蛋白抑制了内质网中GCase的合成,使其不能折叠成正常的构象而无法到达高尔基体加工成熟,未加工成熟的蛋白不具备酶的活性,因此GCase蛋白的表达升高,而酶活性降低。本實验中没有观察到FAC与GCase抑制剂两者的协同作用(析因设计方差分析显示,FAC、CBE两种因素之间无交互作用,因此说明FAC与CBE无协同作用)。

綜上所述,在高铁环境下,SH-SY5Y细胞内GCase的活性降低,蛋白的表达升高。本实验结果为进一步深入研究GCase在PD发病中的作用提供了一定的实验依据。

[参考文献]

[1] BLAUWENDRAAT C, REED X, KROHN L, et al. Genetic modifiers of risk and age at onset in GBA associated Parkinsons disease and Lewy body dementia[J]. Brain,2020,143(1):234-248.

[2] LEE A, GILBERT R M. Epidemiology of Parkinson disease[J]. Neurologic Clinics, 2016,34(4):955-965.

[3] TOFFOLI M, SMITH L, SCHAPIRA A H. The biochemical basis of interactions between Glucocerebrosidase and alpha-synuclein in GBA1 mutation carriers[J]. Journal of Neuroche-mistry, 2020. doi:org/10.1111/jnc.14968.

[4] LUNDE K A, CHUNG J, DALEN I, et al. Association of glucocerebrosidase polymorphisms and mutations with dementia in incident Parkinsons disease[J]. Alzheimers & Dementia: the Journal of the Alzheimers Association, 2018,14(10):1293-1301.

[5] NALLS M A, DURAN R, LOPEZ G, et al. A multicenter study of glucocerebrosidase mutations in dementia with Lewy bodies[J]. JAMA Neurology, 2013,70(6):727-735.

[6] DO J, MCKINNEY C, SHARMA P, et al. Glucocerebrosidase and its relevance to Parkinson disease[J]. Molecular Neurodegeneration, 2019,14(1):36-52.

[7] HRUSKA K S, LAMARCA M E, SCOTT C R, et al. Gaucher disease: mutation and polymorphism spectrum in the glucocerebrosidase gene (GBA)[J]. Human Mutation, 2008,29(5):567-583.

[8] LERCHE S, WURSTER I, ROEBEN B, et al. Parkinsons disease: glucocerebrosidase 1 mutation severity is associated with CSF alpha-synuclein profiles[J]. Movement Disorders, 2020,35(3):495-499.

[9] YANG S Y, GEGG M, CHAU D, et al. Glucocerebrosidase activity, cathepsin D and monomeric alpha-synuclein interactions in a stem cell derived neuronal model of a PD associated GBA1 mutation[J]. Neurobiol Dis, 2020,134:104620.

[10] BLANZ J, SAFTIG P. Parkinsons disease: acid-glucocerebrosidase activity and alpha-synuclein clearance[J]. J Neurochem, 2016,139(Suppl 1):198-215.

[11] XILOURI M, BREKK O R, STEFANIS L. Autophagy and alpha-synuclein: relevance to Parkinsons disease and related synucleopathies[J]. Movement Disorders: Official Journal of the Movement Disorder Society, 2016,31(2):178-192.

[12] HENDERSON M X, SEDOR S, MCGEARY I, et al. Glucocerebrosidase activity modulates neuronal susceptibility to pathological alpha-synuclein insult[J]. Neuron, 2020,105(5):1-15.

[13] JIANG H, WANG J, ROGERS J, et al. Brain iron metabolism dysfunction in Parkinsons disease[J]. Molecular Neurobiology, 2017,54(4):3078-3101.

[14] DE FARIAS C C, MAES M, BONIFACIO K L, et al. Parkinsons disease is accompanied by intertwined alterations in iron metabolism and activated immune-inflammatory and oxidative stress pathways[J]. CNS & Neurological Disorders-Drug Targets, 2017,16(4):484-491.

[15] LAN A P, CHEN J, CHAI Z F, et al. The neurotoxicity of iron, copper and cobalt in Parkinsons disease through ROS-mediated mechanisms[J]. Bio Metals, 2016,29(4):665-678.

[16] YANG W S, SRIRAMARATNAM R, WELSCH M E, et al. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4[J]. Cell, 2014,156(1/2):317-331.

[17] DENG H, WANG P, JANKOVIC J. The genetics of Parkinson disease[J]. Ageing Res Rev, 2018,42:72-85.

[18] TRANCHANT C. Introduction and classical environmental risk factors for Parkinson[J]. Revue Neurologique, 2019,175(10):650-651.

[19] CHESNOKOVA A Y, EKIMOVA I V, PASTUKHOV Y F. Parkinsons disease and aging[J]. Adv Gerontol, 2018,31(5):668-678.

[20] BERGSLAND N, ZIVADINOV R, SCHWESER F, et al. Ventral posterior substantia nigra iron increases over 3 years in Parkinsons disease[J]. Movement Disorders: Official Journal of the Movement Disorder Society, 2019,34(7):1006-1013.

[21] YU Shuyang, CAO Chenjie, ZUO Lijun, et al. Clinical features and dysfunctions of iron metabolism in Parkinson disease patients with hyper echogenicity in substantia nigra: a cross-sectional study[J]. BMC Neurology, 2018,18(1):9-17.

[22] WYPIJEWSKA A, GALAZKA-FRIEDMAN J, BAUMIN-GER E R, et al. Iron and reactive oxygen species activity in Parkinsonian substantia nigra[J]. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 2010,16(5):329-333.

[23] BELAIDI A A, BUSH A I. Iron neurochemistry in Alzheimers disease and Parkinsons disease: targets for therapeutics[J]. J Neurochem, 2016,139(Suppl 1):179-197.

[24] GOZZELINO R, AROSIO P. Iron homeostasis in health and disease[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2016,17(1):130-144.

[25] SUN Y, PHAM A N, WAITE T D. The effect of vitamin C and iron on dopamine-mediated free radical generation: implications to Parkinsons disease[J]. Dalton Transactions (Cambridge, England:2003), 2018,47(12):4059-4069.

[26] GEGG M E, BURKE D, HEALES S J, et al. Glucocerebrosidase deficiency in substantia nigra of parkinson disease brains[J]. Annals of Neurology, 2012,72(3):455-463.

[27] MURPHY K E, GYSBERS A M, ABBOTT S K, et al. Reduced glucocerebrosidase is associated with increased alpha-synuclein in sporadic Parkinsons disease[J]. Brain, 2014,137(Pt 3):834-848.

[28] MISHRA A, CHANDRAVANSHI L P, TRIGUN S K, et al. Ambroxol modulates 6-hydroxydopamine-induced temporal reduction in glucocerebrosidase (GCase) enzymatic activity and Parkinsons disease symptoms[J]. Biochem Pharmacol, 2018,155:479-493.

[29] LUZIO J P, PRYOR P R, BRIGHT N A. Lysosomes: fusion and function[J]. Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology, 2007,8(8):622-632.

[30] KAO J K, WANG S C, HO L W, et al. Chronic iron overload results in impaired bacterial killing of THP-1 derived macrophage through the inhibition of lysosomal acidification[J]. PLoS One, 2016,11(5):e0156713.

[31] MAZZULLI J R, XU Y H, SUN Y, et al. Gaucher disease glucocerebrosidase and alpha-synuclein form a bidirectional pathogenic loop in synucleinopathies[J]. Cell, 2011,146(1):37-52.

[32] WANG R, WANG Y, QU L, et al. Iron-induced oxidative stress contributes to alpha-synuclein phosphorylation and up-regulation via polo-like kinase 2 and casein kinase 2[J]. Neurochem Int, 2019,125:127-135.

[33] GANGULY U, BANERJEE A, CHAKRABARTI S S, et al. Interaction of alpha-synuclein and Parkin in iron toxicity on SH-SY5Y cells: implications in the pathogenesis of Parkinsons disease[J]. Biochemical Journal, 2020. doi:org/10.1042/BCJ20190676.

[34] ROCHA E M, SMITH G A, PARK E, et al. Sustained systemic glucocerebrosidase inhibition induces brain alpha-synuclein aggregation, microglia and complement C1q activation in mice[J]. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling, 2015,23(6):550-564.

[35] XU YH, SUN Y, RAN H, et al. Accumulation and distribution of alpha-synuclein and ubiquitin in the CNS of Gaucher disease mouse models[J]. Mol Genet Metab, 2011,102(4):436-447.

[36] MANNING-BOG A B, SCHULE B, LANGSTON J W. Alpha-synuclein-glucocerebrosidase interactions in pharmacological Gaucher models: a biological link between Gaucher disease and Parkinsonism[J]. Neurotoxicology, 2009,30(6):1127-1132.

(本文編辑 马伟平)