Prognostic significance of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis treated with current standards of care

Anuj Bohra, Thomas Worland, Samuel Hui, Ryma Terbah, Ann Farrell, Marcus Robertson

Abstract

Key words: Hepatic encephalopathy; Cirrhosis; Portal hypertension; Prognosis; Rifaximin;Lactulose

INTRODUCTION

Prognosis in patients with liver cirrhosis varies significantly depending on whether a patient has compensated or decompensated cirrhosis[1,2]. In patients with compensated cirrhosis, median survival is greater than 12 years. By contrast, in patients experiencing a decompensation, commonly defined by ascites, hepatic encephalopathy (HE), variceal haemorrhage and jaundice, survival is far shorter at two years or less[3-5].

HE is defined as a reversible neuropsychiatric complication of liver cirrhosis. It represents the second most common decompensating event after ascites and will occur in 30%-45% of cirrhotic patients during their lifetime[6,7]. HE manifests as a wide spectrum of neuropsychiatric abnormalities and motor disturbance, ranging from mild alterations in cognitive function to coma and death[8,9]. The clinical features of HE define the grade of encephalopathy, with the West Haven criteria most commonly employed to stage the severity of disease[10]. Plasma ammonia levels are typically elevated in patients with HE, however this is not a reliable sign and is not used in the diagnosis of HE[11]. The current treatment priorities in HE are to identify and reverse the underlying precipitants, which include sepsis, gastrointestinal bleeding,medications such as benzodiazepines, opiates and anti-histamines, acid-base disturbances, renal impairment and constipation[2]. Traditionally, pharmacological therapies have aimed to decrease plasma ammonia levels. Lactulose, which decreases colonic pH and plasma ammonia levels has been the mainstay of treatment for many years. More recently, Rifaximin, a broad-spectrum semisynthetic derivative of rifamycin with minimal systemic absorption, has been added to the therapeutic armamentarium in addition to the use of lactulose[12-14]. Multiple other therapeutic options require further trials to clearly define their role in the management of HE[15-18].

The natural history and prognosis of patients with ascites and variceal bleeding has been extensively studied, however, despite its prevalence there is a paucity of literature related to the prognostic significance of HE. Two sentinel studies published prior to the development of rifaximin demonstrated that development of HE was associated with an extremely poor survival in patients with cirrhosis who did not receive liver transplantation[3,19]; Bustamanteet al[19]demonstrated a survival probability of 42% and 23% at one and three years respectively in cirrhotic patients after development of a first episode of acute HE. In the post-Rifaximin era, there is a paucity of literature investigating the prognosis of cirrhotic patients following an episode of HE[20]. To our knowledge, survival of patients with a presentation of HE in the era of rifaximin has yet to be studied in an Australian real-world cohort.

In this study, we evaluated the clinical outcomes and probability of survival amongst cirrhotic patients who presented with acute HE requiring hospital admission and were commenced on rifaximin. In addition, we aimed to identify factors associated with mortality.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient selection and data collection

All patients admitted with HE to three Australian tertiary centres, including one transplant centre, over a 42-mo period from May 2012 to March 2016 who were prescribed rifaximin were identified retrospectivelyviapharmacy dispensing records.Inclusion criteria were that rifaximin must have been commenced during an inpatient admission for HE and continued upon discharge from hospital. Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) diagnosed prior to or during the index admission with HE were excluded from the study. Diagnosis of HCC was established by standard imaging techniques (CT Quad Phase Liver or MRI Liver) and/or serum alpha foetoprotein and/or histological examination. The Human Research Ethics Committee at Monash Health approved the study as audit activity and the committee provided a waiver for informed consent.

图5为使用3种算法对4个不同形状不同规模的数据集进行聚类的准确率比较,可以明显看出改进后算法的聚类准确率保持在90%以上,聚类效果明显优于GP-CLIQUE算法和CLIQUE算法。这是因为使用本文方法对划分后的网格进行处理后,寻回了丢失的稠密区域,提高了聚类质量。而GPCLIQUE算法的准确率比CLIQUE算法略有提高,这是因为虽然GP-CLIQUE算法采用高斯随机采样的方法提升了聚类性能,但还是采用固定宽度划分方法,所以算法性能的提升低于本文算法。准确率计算公式为:Accuracy=ncorrect/n。

For each patient, medical records were manually reviewed to collect baseline demographic data, medical comorbidities, aetiology of liver disease, medication use,laboratory results, evidence of decompensated liver disease, precipitating causes of HE and previous and current treatments of HE. Patient outcome data up to 48-mo following the index admission was collected. Death was determined through hospital medical records and confirmed with a patient's Local Medical Officer if required.Each medical record was independently reviewed by two reviewers and any discrepancies in data were referred to a third reviewer. All patients were risk stratified using the model for end stage liver disease (MELD) and Child-Pugh (CP)scores; when calculating the CP score, the serum albumin level prior to intravenous albumin administration was used. The diagnosis and grade of HE was determined using established West Haven criteria[9].

All patients were followed-up from the date of rifaximin commencement until the date of death, liver transplantation or last known survival up to 48-mo following index admission. The primary outcome was 12-mo survival following the commencement of rifaximin. The secondary outcome was to identify patient-specific prognostic factors at the time of commencement of rifaximin that would be useful in determining suitability for a liver transplant.

Treatment protocols for hepatic encephalopathy

Patients with cirrhosis and HE are admitted under a specialist Gastroenterology or Liver Transplant Unit. In all patients treatment of HE consists of identification and correction of possible precipitating factors. Intravenous albumin (1.5 g/kg per day) is typically administered consistent with evidence that it shortens the duration of acute HE[21]. In our centres, regular Lactulose (administered orally or rectally in the setting of reduced mental state) is given as first-line therapy and rifaximin is typically reserved for patients with recurrent or refractory HE.

Statistical analysis

Survival probability curves were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method.Univariate survival analysis was performed using the Cox proportional hazards model to analyse each considered variable, which included demographic data,maximal grade of HE, precipitating factors of HE, MELD and CP scores and clinical and laboratory data at the time of HE. Variables which reached statistical significance(P≤ 0.05) in the univariate analysis were subsequently included in a multivariate analysis to identify variables independently associated with survival. We used the stepwise Cox regression procedure (variables entered ifP≤ 0.10, variables removed ifP≥ 0.15). Statistical analysis was carried out usingRfor windows (version 1.1.419)through the survival package as well as through MedCalc (version 19.0.7).

RESULTS

Total 365 patients with acute HE necessitating hospital admission were prescribed rifaximin during the study period. Total 177 (48%) patients were excluded from the study, leaving a total of 188 patients for analysis (Figure 1). Reasons for exclusion included: pre-existing use of rifaximin prior to admission in 134 (37%) patients, the presence of HCC in 41 (11%) patients and no identifiable start date for rifaximin in 2(0.5%) patients.

Characteristics of patients

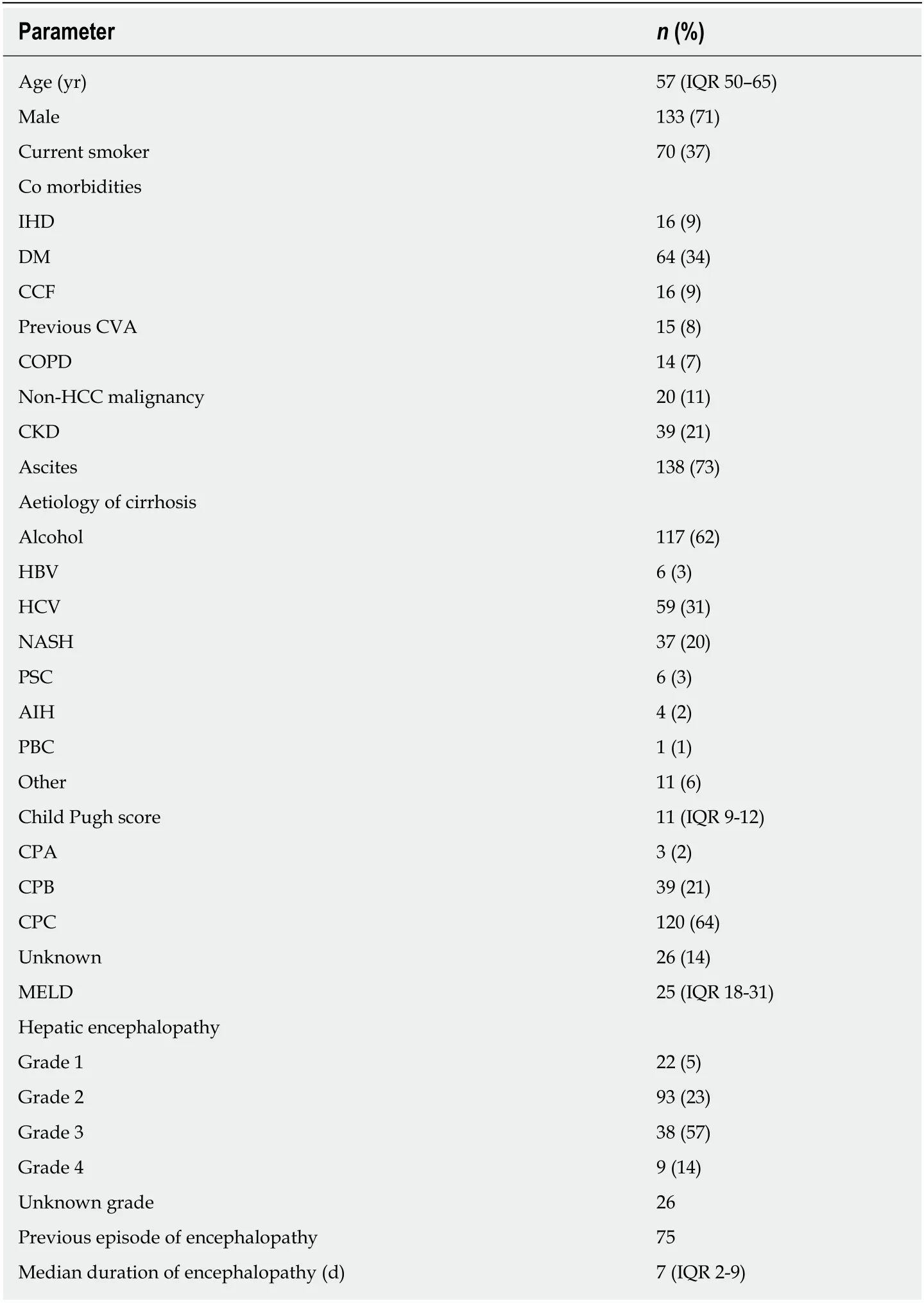

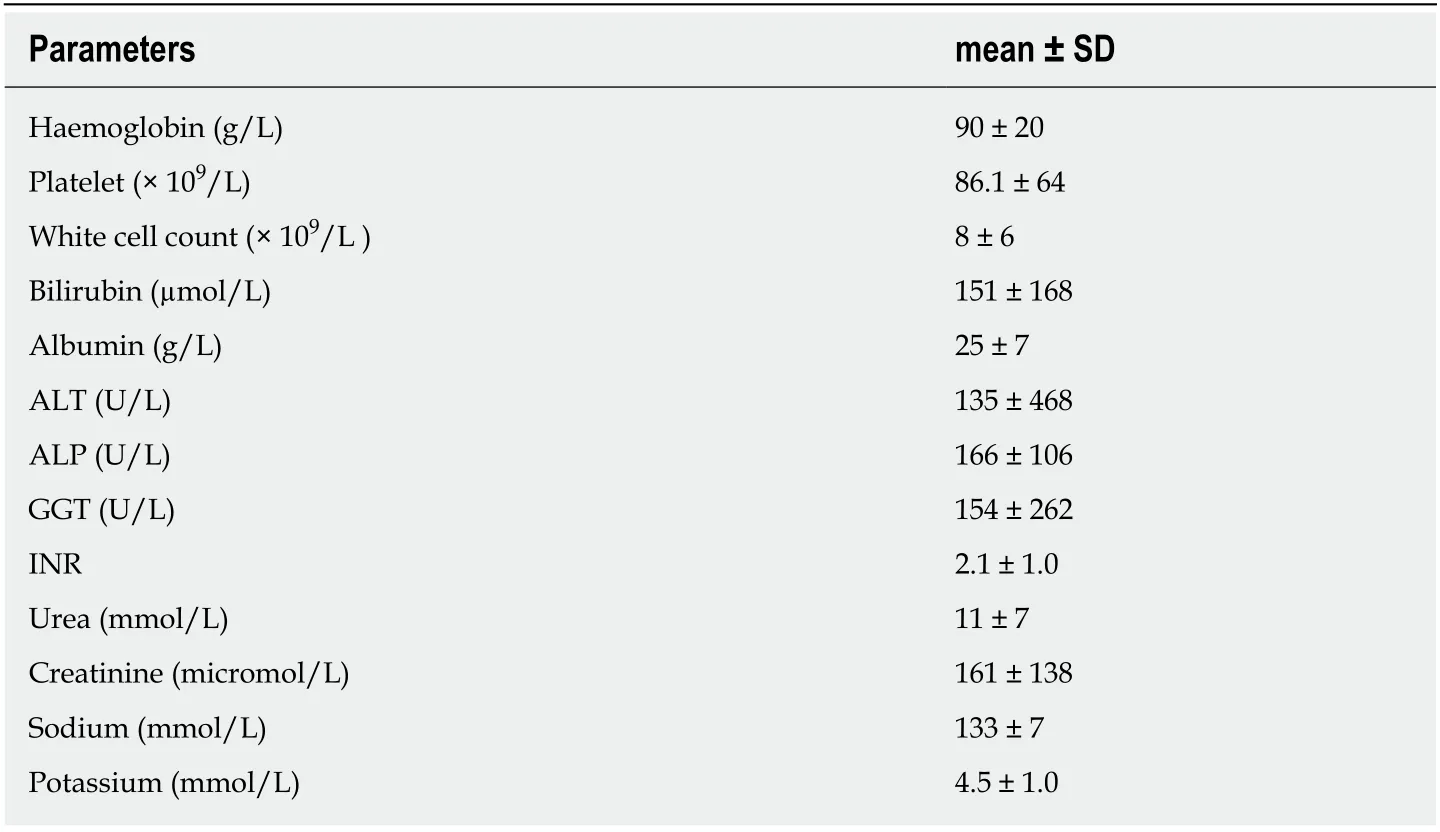

There were 133 males and 55 females with a median age of 57 years (IQR 50-65). All patients had established cirrhosis based on hospital records compiled from previous histological and radiology data. The most common aetiologies of cirrhosis were:Alcohol (70 patients), non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (24 patients) and hepatitis C (20 patients) (Table 1). Four patients had previously received a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt procedure. The median CP score was 11 (IQR 9-12) and 3, 39 and 120 patients had Child A, B and C cirrhosis respectively on admission; 26 patients had insufficient documentation to accurately calculate a CP score. The median MELD score was 25 (IQR 18-31) with 77% patients having a MELD score ≥ 15. Baseline patient characteristics and laboratory data are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

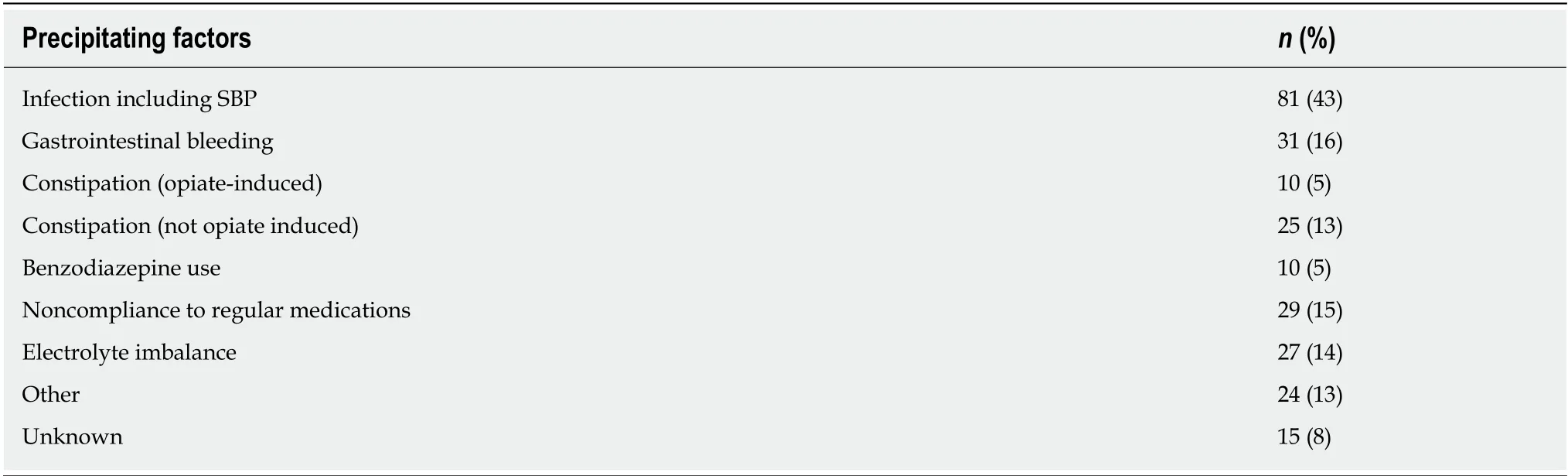

A likely precipitant of decompensated cirrhosis with acute HE was identified in 173(92%) patients (Table 3); in many patients this was felt to be multi-factorial with more than one precipitant identified. Alone or in combination, the most commonly identified causes for HE were: Infection (including spontaneous bacterial peritonitis)in 81 (43%) patients, gastrointestinal bleeding in 31 (16%), constipation in 35 (19%)and non-compliance with prescribed medications in 29 (15%). In relation to the severity of HE, the West Haven HE grades were available in 162 (86%) patients (Table 1), with 22 (14%), 93 (57%), 38 (23%) and 9 (5%) patients recording a maximal HE grade of 1, 2, 3 and 4 respectively. Thirty-three (18%) patients required admission to an intensive care ward. In addition to rifaximin, 166 (88%) patients received either oral or rectal lactulose with a mean dose of 177 mL, 13 (7%) patients received macrogol (polyethylene glycol “3350”) and 19 patients received other forms of aperients.

Documentation of resolution of encephalopathy was identified in 133 patients prior to discharge with a median duration to resolution of symptoms of 7 d (IQR 2-9 d). Of the remaining 55 patients, 20 died prior to resolution of HE and in the other 35 documentation was insufficient to determine whether HE has resolved at the time of discharge.

Mortality and prognostic factors

Within a mean follow-up period of 12 ± 13 mo, 107 (57%) patients died and 32 (17%)received liver transplantation. 42 patients died during or within 30-d of the index admission in which rifaximin was commenced. Causes of death included liver failure in 61 (57%) patients, sepsis in 19 (18%), unknown cause in 12 (11%), non-HCC malignancy in 4 (4%), cerebrovascular accidents in 4 (4%), gastrointestinal bleeding in 4 (4%), ischemic gut in 1 (1%) and cardiopulmonary arrest in 2 (1%) patients. The probably of survival in the entire cohort was 44% at 12-mo, 35% at 24-mo and 29% at 36-mo (Figure 2).

Twenty-seven variables were included in the univariate analysis, of which 10 were significantly associated with a poor prognosis: Hepatitis C infection, infection as the precipitant for HE, serum bilirubin, urea, creatinine, international normalised ratio(INR), white cell count, CP score, MELD and a MELD score ≥ 15 (vs≤ 15). These variables were subsequently introduced into the multivariate analysis. The multivariate analysis (performed in the 159 patients in whom all variables were available) identified two variables as statistically significant, independent prognostic factors: A MELD score ≥ 15 and INR (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Hepatic encephalopathy remains a common complication in patients with liver cirrhosis. Our study demonstrates that development of HE necessitating hospital admission in cirrhotic patients is associated with a short life expectancy in the absence of liver transplantation despite current standards-of-care. The cumulative survival at 12-, 24- and 36-mo were 44%, 35% and 29% respectively with the majority of patients dying from complications of decompensated liver disease or liver failure. At multivariate analysis the variables significantly associated with mortality were a MELD score ≥ 15 and INR.

Figure 1 Recruitment flowchart. HE: Hepatic encephalopathy; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

Our study represents one of the largest real-world studies to investigate the prognostic significance of HE in the era of rifaximin. Study inclusion criteria were broad and simple, including all cirrhotic patients admitted with acute HE and commenced on rifaximin to three metropolitan tertiary centres in Australia, including one transplant centre, with a total catchment area of approximately two million people. The study population consisted of patients with decompensated cirrhosis managed on a specialist Gastroenterology ward who received treatment consistent with recent practice guidelines. Study results thus represent real-world data and should be widely applicable to other treating centres.

The results of this study correlate with sentinel studies from the pre-rifaximin era.Bustamanteet al[19]demonstrated a similar 12-mo survival probability of 42% amongst patients experiencing their first presentation with HE where lactulose was the primary pharmacological management option. In addition, Stewartet al[3]demonstrated that higher grades of HE corresponded to increased mortality rates with an overall survival of less than 20% at 36-mo in patients presenting with Grade 3 HE[3,19].

Following the introduction of rifaximin various studies have sought to assess whether the survival probability has improved in cirrhotic patients following an episode of HE. Sharmaet al[8]demonstrated in a randomised control trial that the 10-d survival following the commencement of rifaximin plus lactulose for the management of HE was superior to patients receiving lactulose alone. A larger retrospective cohort study by Kanget al[22], of 421 patients with HE of whom 145 received rifaximin found rifaximin use to be independently associated with a decreased risk of death. Despite a similar median CP score (10vs11), this study demonstrated a survival probability at 12-, 24-, 36- and 48-mo of 70%, 68%, 64% and 63% respectively[22], significantly higher than the cumulative survival found in our cohort. The likely reason for this discrepancy in survival is that in the Kanget al[22]study, patients were enrolled after discharge from the index HE admission and patients who died within 2-d of recovery were excluded. Consistent with the study by Bustamanteet al[19], we elected to enrol patients during the index admission in which rifaximin was commenced and patients in our cohort had a 22% 30-d mortality. Furthermore, in Australia, prescribing guidelines necessitate that rifaximin be used only in recurrent or refractory episodes of HE and thus it is typically employed as a second-line agent after Lactulose.Consistent with this, 40% of our patient cohort had experienced an episode of HE prior to the index admission.

Within our cohort, multiple clinical and standard laboratory variables were significantly associated with a poor prognosis at univariate analysis. Five laboratory variables were independently associated with a poor prognosis: Increased serum bilirubin, urea, creatinine, INR and decreased white cell count. Of these variables,bilirubin, renal function and INR are commonly utilised in prognostic risk stratification algorithms and have clear relationships with poor prognosis in patients with liver cirrhosis[23,24]. In addition, Childs Pugh C class cirrhosis and a MELD score ≥15 were both associated with a poor prognosis which is in keeping with their known value in prognosticating survival in advanced liver disease[23,24]. The prognostic significance of leukopaenia in HE requires further investigation. Other studies have not found a low white cell count to be a significant prognostic factor[19], however Qamaret al[25]demonstrated that leukopenia in patients with compensated cirrhosis predicted and increased mortality. Following multivariate analysis, a MELD score ≥15 and INR were found to be independently associated with a poor prognosis. A MELD score ≥ 15 was selected as the cut-off given data that patients with a MELD >15 have higher mortality and shortened survival compared to those who proceed toliver transplantation assessment[26]. All measured components of the MELD were found to be prognostically significant within the univariate analysis but only an elevated INR was independently significant at multivariate analysis.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of study patients

Interestingly, in our study the grade of HE did not reach statistical significance in predicting mortality in either univariate of multivariate analysis. This finding is discordant with some previous studies including the paper by Bustamanteet al[19], in which higher grades of HE were found to be significant at univariate analysis but not on multivariate analysis. In addition, Bajajet al[13]performed a large retrospective analysis of patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis and HE, finding that higher grades of HE were associated with a higher 30-d mortality. By comparison, Stewartet al[3]found on multivariate analysis that in hospitalised patients with HE, the presence of HE was a strong predictor of mortality however there was no difference detected between Grades 2 and 3 HE. One possible reason for our findings may be a type-2error with insufficient patient numbers to demonstrate a statistically significant difference between Grades of encephalopathy. In our cohort, 80% patients had a maximum encephalopathy grade of 2 or 3 with few patients diagnosed with Grades 1 or 4.

Table 2 Baseline laboratory parameters

In our cohort, the vast majority of patients had an identifiable precipitant for the development of HE. Overwhelmingly, HE occurred in patients with advanced,decompensated cirrhosis and portal hypertension and was most commonly associated with other co-existing complications of decompensated cirrhosis such as ascites with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and gastrointestinal bleeding. This is consistent with previous observations that HE occurs relatively late in the natural history of cirrhosis and previous studies have also demonstrated an association between MELD score and the development of HE[14]. Indeed, it has been postulated that for HE to occur,decreased hepatic function and portosystemic shunting are necessary to allow putative toxic molecules to reach the cerebral circulation[3].

Our study has certain limitations including its retrospective design, meaning all data collection was ascertained through existing clinical records which were generated by multiple health practitioners in a non-standardised fashion. Inherent with retrospective studies, not all data points were available in all patients which potentially affects the statistical analysis. Errors were minimised by using a small number of data collectors who entered information into a standardised database and each medical record was independently reviewed by two researchers. Secondly, our study population was recruited from tertiary centres and consisted entirely of patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis with portal hypertension. All patients required hospital admission for acute HE and 73% had concurrent ascites. The median Child Pugh score of 11 and MELD score of 25 reflects that our population had advanced liver disease and were unwell at the time of hospital admission. Patients with advanced liver disease have a poor prognosis irrespective of the development of encephalopathy. The 30-d mortality in this study was 22% which is higher than that recorded by patients with acute variceal bleeding in recent studies[27,28]and again reflects that acute HE is associated with a very guarded prognosis.

Finally, due to the retrospective nature of the study it was not possible to accurately assess nutritional therapy during the acute course of encephalopathy and this is obviously an important factor in any patient with decompensated cirrhosis.

In conclusion, the development of HE in patients with cirrhosis still confers an extremely poor prognosis with low probability of transplant-free survival despite current standards-of-care. In all cirrhotic patients, development of HE should prompt consideration of the appropriateness of urgent liver transplantation assessment.Further prospective studies are required to investigate whether there is a survival benefit of rifaximin in patients with advanced cirrhosis and encephalopathy.

Table 3 Precipitating factors for hepatic encephalopathy (alone or in combination with other factors)

Table 4 Hazard ratio for the different variables investigated by univariate analysis and multivariate analysis as possible prognostic factors in 188 cirrhotic patients presenting with hepatic encephalopathy and commenced on rifaximin

Figure 2 Transplant-free survival probability following commencement of rifaximin.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a common neuropsychiatric complication in patients with liver cirrhosis and represents the second most common decompensating event after ascites. The current treatment approach for HE includes the reversal of identifiable underlying precipitants and the use of ammonia-lowering agents such as lactulose and rifaximin.

Research motivation

Previous sentinel studies have demonstrated that development of HE is associated with extremely poor transplantation-free survival. There remains a paucity of literature examining the natural history and prognosis of HE in the post-rifaxamin era.

Research objectives

We aimed to evaluate the clinical outcomes and survival probability of cirrhotic patients who developed acute HE requiring admission to hospital and were treated with rifaxamin in addition to current standards-of-care. In addition, we aimed to identify factors at the time of HE that could predict mortality and highlight the need to consider liver transplantation.

Research methods

We performed a retrospective, multi-centre analysis of 188 patients admitted with HE and commenced on rifaxmin with a mean follow-up period of 12 ± 13 mo. Survival probability curves were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Univariate survival analysis was performed using the Cox proportional hazards model. Variables which reached statistical significance (P≤0.05) were subsequently included in a multivariate analysis to identify factors independently associated with survival using the stepwise Cox regression procedure.

Research results

In patients with acute HE requiring hospital admission and treated with current standards-ofcare, the probability of survival remains poor with a 1- and 3-year survival probability of 44%and 29% respectively. The majority of patients have an identifiable precipitant for HE and the most common cause of death was liver failure or complications of decompensated cirrhosis.Baseline international normalised ratio and a model for end stage liver disease score ≥ 15 reached statistical significance on multivariate analysis to predict mortality.

Research conclusions

Despite advances in treatment, the development of acute HE in cirrhotic patients continues to confer an extremely poor prognosis and a low probability of survival in the absence of liver transplantation. Both international normalised ratio, a marker of synthetic liver dysfunction, and model for end stage liver disease score, which is well-validated to prognosticate survival in advanced liver disease, were able to independently predict survival probability at the time of admission.

Research perspectives

The development of HE in a cirrhotic patient is an extremely serious complication that typically occurs late in the disease process and confers an extremely poor prognosis. Inpatient management of HE with current standards-of-care can successfully resolve the episode of HE in the majority of cases but has limited ability to affect the natural sequalae of the advanced disease state. In all cirrhotic patients, the development of HE should prompt consideration of the appropriateness of liver transplantation. Further prospective studies would be useful to investigate the survival benefits of rifaxamin in patients with advanced cirrhosis and HE.

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年18期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年18期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Folic acid attenuates high-fat diet-induced steatohepatitis via deacetylase SlRT1-dependent restoration of PPARα

- Genetic association analysis of CLEC5A and CLEC7A gene singlenucleotide polymorphisms and Crohn's disease

- Hepatitis B virus recurrence after liver transplantation: An old tale or a clear and present danger?

- Natural products that target macrophages in treating non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- Ectopic hepatocellular carcinoma mimicking a retroperitoneal tumor:A case report

- Annexin A2 promotion of hepatocellular carcinoma tumorigenesis via the immune microenvironment