Intensive Devotion

By Liu Zhongdi

On the eve of Lunar New Year in 2020, it occurred to me that the novel coronavirus opened the Pandoras Box and unleashed a public health crisis in Wuhan, the hardest hit Chinese city by the epidemic. A wave of extreme uneasiness wrapped everyone since the spread of the epidemic was incredibly rapid and discreet.

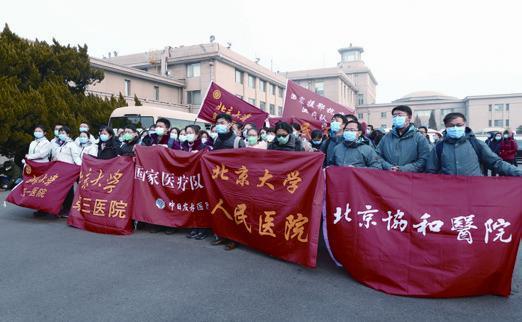

On January 26, the fi rst medical team of Peking University Peoples Hospital rushed to Wuhan to treat patients contracted the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Their determination and bravery made my heart fl utter, and then I decided to join the battle when I was informed on February 2 that another batch of medical teams would be formed soon. My wife helped me pack luggage and bought disposable items that might be useful.

On February 7, I left my house for the hospital at 5 a.m. It was cold and dark outside. Members of the third batch of medical teams quickly assembled at the hospital. Prior to our departure, Jiang Baoguo, president of the hospital, boosted our morale with rousing remarks. I was brimming with ambition, strength and power.

As I was looking down at the sea of clouds below me from the plane, I thought of my father. When the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) broke out in China in 2003, my father, as the head of his department, rushed to the frontline on the fi rst notice and took charge of the imageological diagnosis of patients. I remembered witnessing this when I was 13, and thus hoping to become someone like him, a white-clad warrior who saved the lives of many. My father had passed away before he could see me dress in the same white gown he once did. But it did not matter, because I had never felt so close to him as I did then.

At 3 p.m., we arrived in Wuhan. Walking out of the eerily quiet airport lobby, I was greeted by a piercing wind. It was the fi rst time that I had ever been to Wuhan, and it was also the fi rst time that I had felt such bitter, chilly air.

On the way to the hotel, there were no other cars or people on the street. Through the windows of the residential buildings we passed by, not a single moving fi gure could be seen. The whole city seemed to have stopped living. It was hard to imagine the once bustling metropolis had turned into a lifeless ghost town in such a brief amount of time. Everyone felt nervous in the overwhelming ominous atmosphere.

After arriving at the hotel, our whole team immediately received emergency training. We were introduced with details regarding the conditions of the medical wards and given updated information about the patients. We also received training on personal protection and precautions.

The battle begins

On the next day, our team visited the newly established intensive care unit (ICU) ward at the Tongji Hospital. When we arrived, the team leader and the hospital support staff were still busy making fi nal adjustments to the medical equipment and the information system.

Immediately, everyone on the team was busy with their respective tasks: doctors were managing the medical record system, while nurses were busy inspecting medical instruments and checking the drugs. We were all busy preparing for the impending battle ahead. It took only 24 hours for the ICU to be fully prepared for incoming patients!

Around 10 p.m., the first wave of patients streamed into the ICU, signaling the beginning of our battle. I entered the changing room prior to their arrival, wearing protective clothing, gloves, shoe covers, goggles and face shields. Everyone on our team checked up on each other for any misplacement or gaps in our safety equipment. Once having put on the entire outfi t, immediate discomfort started to arise from every part of my body: the sealed glasses were placed tightly around my eyes, creat- ing impaired vision due to the foggy lenses; the tightly fit goggles exerted unbearable pain and pressure on the bridge of my nose; my hands were tightly bound by fi ve layers of gloves, making it diffi cult to even extend or fl ex my wrists; and it was hard to breathe through normally when wearing the airtight masks. It became evident to us all that the following days at the hospital would be challenging.

In order to enter the contaminated zone, we had to go through four buffer zones and fi ve protective doors. For safety, the team members made sure we entered the ward in separate groups. Tension was building up with every door that was opened in front of us.

When the last door was closed behind us, I stood for a few seconds attempting to breathe calmly, and meticulously scanned the scene in front of me, looking for patients that were in an urgent need of treatment.

More and more patients started to cram up outside of our unit as our shift progressed. Patients who were diagnosed and registered were directed to different wards according to the severity of their illness. Doctors and nurses cooperated with each other, making arrangements and collecting medical records. We ensured that symptomatic treatment was given on time to each patient and every person had their needs met when requested.

The fi rst group of patients that arrived made a lasting impression on me. They were all in critical condition due to their pre-existing chronic illnesses and many of them were elderly patients with severe damage to their respiratory and circulatory systems. When consulting their symptoms, many of them mumbled. Since most of them spoke in a dialect, communication was difficult at first. I remembered clearly during training that medical professionals were advised to maintain a certain distance from the patients, but during consultations, the doctor-patient seating distance, patients dialect and mumbled responses combined made it diff icult for me to make sense of what they said. I had to ask several questions over and over again, at times even closing up to the patients to listen. The entire routine eventually proved to be highly emotionally draining, and it was devastating to hear similar accounts again and again of how patients were tortured by the novel coronavirus.

Four hours passed quickly, and with the blink of an eye my shift had come to an end. As I was getting off my shift, it dawned on me that I had completely forgotten about the discomfort I initially felt when I fi rst put on my protective gear. After I took off my gear, I noticed that my inner layers were all wet, and the wetness brought touches of coldness to my skin when exposed to the fresh air. When the foggy glasses were finally taken off, the area around my eyes swelled up immensely, and my nose bridge and cheeks were left with deep indentations on my skin. Stinging pain was felt all over, especially on the areas where the protective gear was tightly bound on my body.

A dynamic Wuhan returns

Through continuous and valiant efforts, many patients gradually recovered. Patients started to be discharged from the hospital on February 21. It was defi nitely a hard-earned milestone.

The work went on, and before I realized, the last day of February had quickly arrived. I turned 30 on March 1, and I spent my birthday on the frontline combating COVID-19 with my fellow colleagues. In the past, I usually made self-deprecating jokes claiming that I was an old millennial. Now, instead of making fun of my age, I felt an enormous sense of honor to be one of the young medical professionals in the battle against this epidemic. What was more exciting to me was that on March 15, 14 days after my birthday, Chinese President Xi Jinping wrote a letter to the post-90s generation in the medical teams of Peking University and extended sincere greetings to the young people working in various positions to prevent and control the pandemic. As a member of this age group, I was lucky to receive a reply from President Xi and it was an honor and a privilege to be recognized and encouraged by him!

In his letter, President Xi encouraged us to serve the people, strive to improve our skills through hard work, and develop our capability through practice. As a medical worker and a millennial, I am bound by my duty to serve my country and the people with my knowledge and skills. While I was working in Wuhan, I was frequently touched by the friendship that existed all around me. Whether it was between the medical team members, or between patients and medical staff, everyone made sure to always look for the silver lining in times of darkness. Over the course of my time in Wuhan, I took notice of the little things that mattered, and I was constantly reminded of how united China has become when we were all fi ghting the same battle.

As the weather in Wuhan started to get warm, I saw the early cherry blossoms on the sides of the road on my way to work. I did not know exactly when they started to blossom, but just like when silver linings appear in dire times, new life always emerges when least expected. Before we all realized, spring had arrived and transformed Wuhan into a lively, cheerful, and resilient city we once knew.