A Long Way Back From 2004 to 2020

By Emma Shleifer

In the early hours of the morning in Shanghai, 2004, a man pulling a three-wheel cart cycles through the streets.

Hunched over his handlebars, he meanders through the jumble of alleyways crowded with furniture being sold by elderly couples, passing under clotheslines tensed between the cramped backroads of buildings. He cruises by a man cooking breakfast outside his repair shop and zigzags through the heaps of bamboo poles waiting to be fashioned into scaffolding. Using his bell often, he edges forward to the soundtrack of his loudspeaker blaring never-ending announcements too muffled to understand.

If there is one sound that encapsulates my childhood, it is the cart mans loudspeaker blaring through my neighborhood.

Down the street from where I lived, there was what seemed to me Alibabas second cave (before it went online). There were miles of colorful fabric and imitation brands, a humming human wave and measuring tapes that pranced in the air. Men on breaks smoked on steps, watching couples dancing in Fuxing Park, while salespeople tried to push pamphlets in everyones hands. For some unfathomable reason, they were always selling watches.

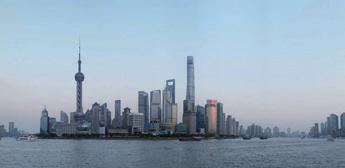

When I returned to Shanghai earlier this year to escape the subzero temperatures that had frozen Beijing, I spent the fi rst day walking from east to west, making a customary visit to the Bund, where a dozen languages buzzed as tourists posed by the river, more numerous and international than I remembered. I was so overjoyed to be back where I had spent most of my childhood that it took me another day to notice the city.

The cart man was still swerving up and down the planetree-lined roads and the shopkeeper was still cooking breakfast on his doorstep. But as I traced further back, I was forced to acknowledge that the sidewalks of bamboo poles, cabbage sales and creaking chairs were long gone. Standing at the end of my childhood street, I realized I had never seen it so neat.

Friends, nostalgic for their former haunts that they found were often torn down or unrecognizable, had told me about this. I visited my friends grandparents house feeling the same way. The exterior looked like a curious combination of new paint and old cement, and I wondered if their room still sported yellowing calendars, if the fl owery covers on the sofa bed where we sat for tea remained or if the closet still held the red tin box of biscuits extracted only for guests. Seeing the fresh white paint and knowing they had moved in with their son when state-led renovations had begun a long time ago, I doubted it.

The old building where shopkeepers smoked during breaks was gone. In its stead gleamed a tidy multistory mall showing off brand names. I had to do a double take. But across the street, with music blasting, women still danced in formation in the soft evening, their routine untroubled by the new malls blinding lights.

It took me another day trudging through the central streets to realize that Shanghai had not been fundamentally altered. True, most of the busy backwaters of stacked houses have been demolished, old shops have closed, English-language signs have been removed (as English-speaking residents in this neighborhood have dwindled), and a pajama-clad barber no longer offered haircuts under the freeway. But the bustling spirit of the port city that I most remembered from childhood still pierces through the fresh cement. In the middle of quiet roads, parents continue to push strollers on sunny weekends. The woman in the corner shop still patiently waits for you to struggle through the stalls before offering suggestions. There is still the same curiosity to explore and connect with the world, experimenting with trends and creating new ones.

But the contrasts are also growing. One street away from trendy Xintiandi, two housekeepers sit on plastic stools waiting for clothes to dry above the pavement.

Of course, it is unreasonable to expect a city to remain just as you left it in childhood, but luckily, Shanghais charm goes beyond its routines and buildings. The magic is in how it adapted faster than any one person ever could, mixing the familiar with the alien.

Our professors often remind us how the busy main roads outside Peking University used to be tree-shaded fi elds and dirt paths. Although enormous, the scale of metamorphosis of the urban Chinese landscape is often diffi cult to appreciate. As a relative newcomer to Beijing, the capitals transformation has remained mostly superficial to me. Seeing Shanghai through my adult eyes brought me a few millimeters closer to grasping the pace of transformation. It sharpened my appetite for more, while reaffi rming what everyone who seeks China knows: the country will always move faster than you. But through the noise, just out of reach of childhood, I am happy that I can still hear the bell and the loudspeaker of the cart man.