Esophageal tuberculosis complicated with intestinal tuberculosis: A case report

Lei Mao, Xue-Ting Zhou, Ji-Pin Li, Jun Li, Fang Wang, Hui-Min Ma, Xiao-Lu Su, Xiang Wang,Department of Gastroenterology, The Second Hospital of Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, Gansu Province, China

Abstract

BACKGROUND

Although the overall incidence of tuberculosis in underdeveloped areas has increased in recent years, esophageal tuberculosis (ET) is still rare. Intestinal tuberculosis (ITB) is relatively more common, but there are few reports of ET complicated with ITB. We report a case of secondary ET complicated with ITB in a previously healthy patient.

CASE SUMMARY

A 27-year-old female was hospitalized for progressive dysphagia, retrosternal pain, acid regurgitation, belching, heartburn, and nausea. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed a mid-esophageal ulcerative hyperplastic lesion. Endoscopic ultrasonography showed a homogeneous hypoechoic lesion, with adjacent enlarged lymph nodes. Biopsy histopathology showed inflammatory exudation,exfoliated epithelial cells and interstitial granulation tissue proliferation.Colonoscopy revealed a rat-bite ulcer in the terminal ileum and a superficial ulcer in the ascending colon, near the ileocecal region. The ileum lesion biopsy showed focal granulomas with caseous necrosis. Polymerase chain reaction for Mycobacterium tuberculosis was positive in the esophageal and ileum lesion biopsies. The T-cell spot tuberculosis test was also positive. The patient was diagnosed with secondary ET infiltrated by mediastinal lymphadenopathy and complicated with ITB, possibly from the Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected esophageal lesion. After 2 mo of anti-tuberculosis therapy, her symptoms improved significantly, and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed healing ulcers.

CONCLUSION

When dysphagia or odynophagia occurs in patients at high-risk for tuberculosis,ET should be considered.

Key words: Esophageal tuberculosis; Intestinal tuberculosis; Dysphagia; Endoscopic ultrasonography; Tuberculosis drug therapy; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Intestinal tuberculosis (ITB) is the sixth most common type of extrapulmonary tuberculosis, accounting for only 2% of tuberculosis cases[1]. Esophageal tuberculosis(ET), which is usually associated with mediastinal lymphadenopathy, is an even rarer form of extrapulmonary tuberculosis, accounting for only 2.8% of gastrointestinal tuberculosis[2]. There are few reports of ET complicated with ITB.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 27-year-old woman presented to our hospital with a one-month history of progressive dysphagia, accompanied by post-sternal pain, belching, acid regurgitation, heartburn, and nausea, with no fever, cough, abdominal pain,gastrointestinal bleeding, night sweats or weight loss.

History of present illness

An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy performed in another hospital revealed a protruding lesion in the middle esophagus, which was considered an esophageal leiomyoma.

History of past illness

She had no significant past medical history.

Personal and family history

There was no pertinent family history.

Physical examination upon admission

There was no obvious abnormality in the patient’s physical examination.

Laboratory examinations

Routine blood tests were normal, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein. The liver and kidney functions were normal. The human immunodeficiency virus antibody was negative. The T-cell spot tuberculosis test was positive. Autoimmune-related antibodies such as ANA, ANCA, AMA, LMA, and ASMA were negative.

Imaging examinations

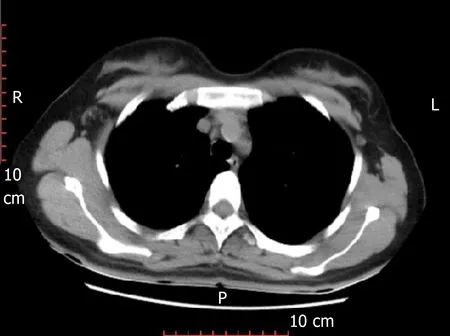

The enhanced chest computed tomography showed local thickening of the esophageal wall with moderate enhancement (Figure 1).

Further diagnostic work-up

Figure 1 Enhanced chest computed tomography. Computed tomography shows local thickening of the esophageal wall with moderate enhancement.

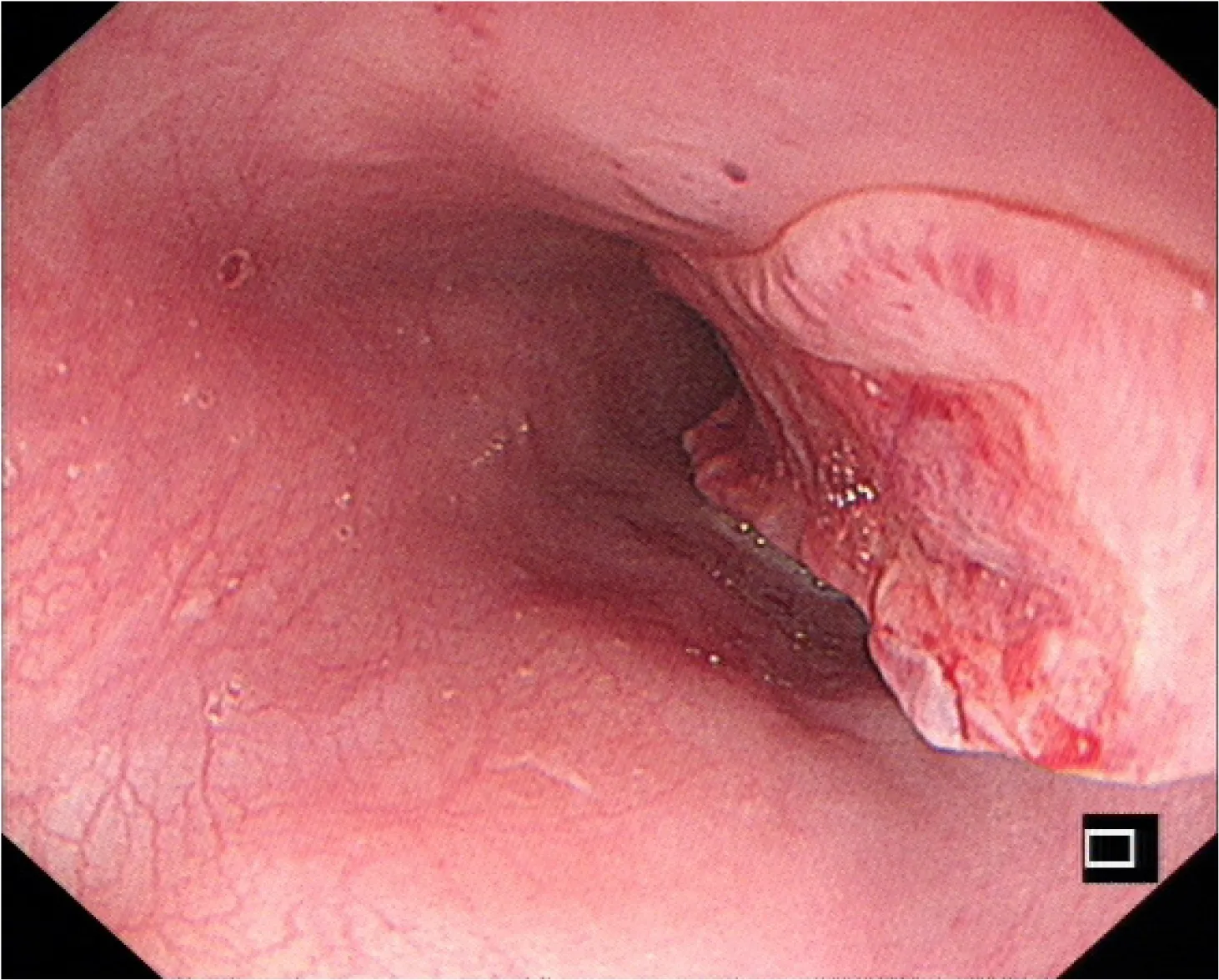

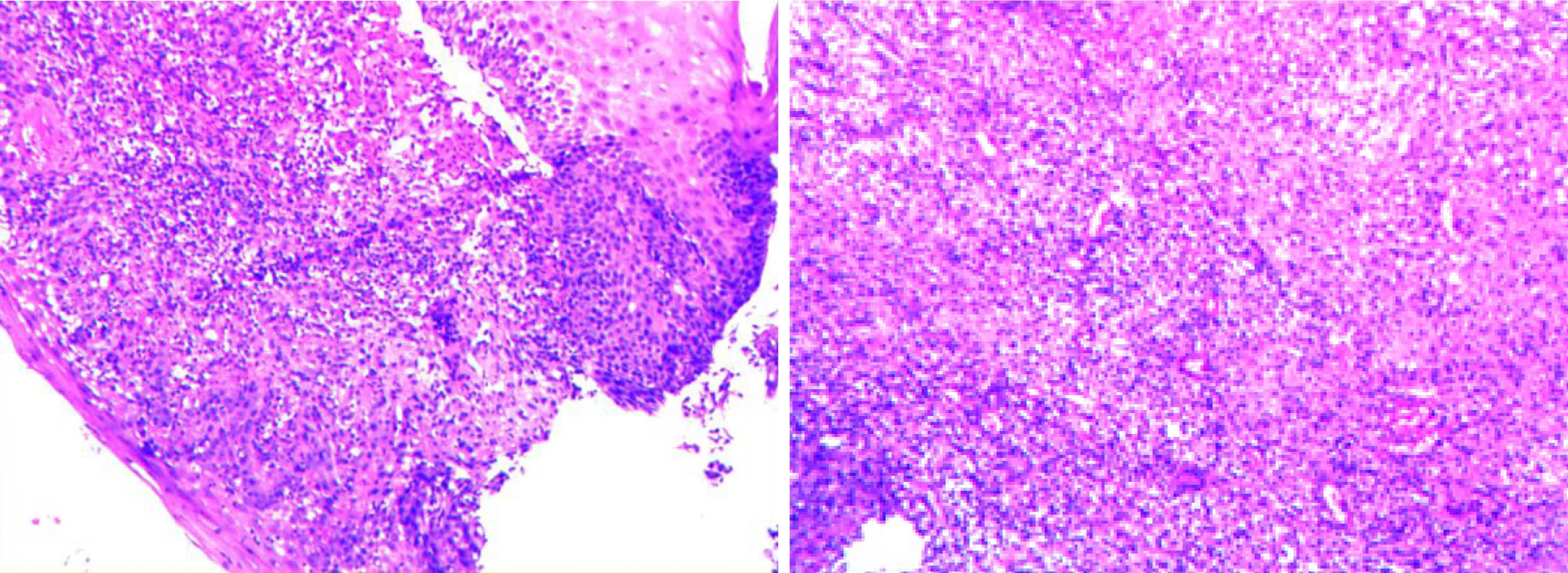

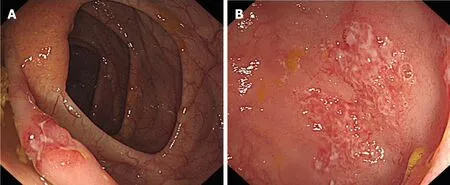

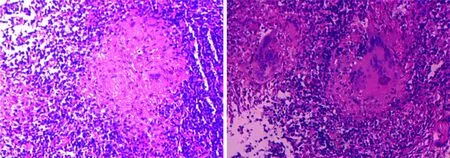

An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was repeated in our hospital and showed a 1.5 cm plate-shaped ulcerated hyperplastic lesion in the middle esophagus, about 26-30 cm from the incisors, with a central depression, erosion and slight bleeding (Figure 2).An endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) was performed and showed a homogeneous hypoechoic lesion protruding into the esophageal lumen, with mucosal layers that had disappeared and fused, and 17.5 mm × 21.3 mm enlarged lymph nodes adjacent to the esophageal lesion (Figure 3). Three biopsy specimens were taken from the esophageal lesion and pathologic results showed epithelial detachment and interstitial granulation tissue hyperplasia under inflammatory exudation (Figure 4). The polymerase chain reaction forMycobacterium tuberculosis(TB–PCR) test was positive.A colonoscopy revealed an irregular ulcer in the terminal ileum, with a rat-bite border and a thin white moss covering at the bottom, and a shallow ulcer of about 0.5 cm ×0.6 cm in the ascending colon, near the ileocecal region, with an irregular border and congested edematous peripheral mucosa (Figure 5). Two biopsy specimens were taken from the lesion at the terminal ileum and pathologic results revealed that the mucosa was in an acute inflammatory activity period of chronic inflammation, with decreasing or disappearing crypts in some areas, and some small focal granulomas in the stroma, which were composed of epithelial cells. Some caseous necroses were observed in the center of the granulomas, and the granulomas were surrounded by numerous lymphocytes (Figure 6). TB-PCR of these specimens was also positive.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Based on the above evidence, the patient was diagnosed with ET, secondary to mediastinal lymphadenopathy, and complicated with ITB, which was caused byMycobacterium tuberculosisinfection from the esophageal lesion.

TREATMENT

The patient was treated with anti-tuberculosis therapy (ATT) (2HRZE) for 2 mo(isoniazid 300 mg QD, rifampicin 0.45 g QD, pyrazinamide 0.5 g TID and ethambutol 0.75 g QD).

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

After 2 mo of ATT, her symptoms improved significantly, and follow-up upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed ulcer healing with scar tissue (Figure 7). Neither liver function impairment nor intolerance to antitubercular drugs was observed. ATT will be administered for another 4 mo (4HR, isoniazid, rifampicin), and we will continue to follow up on her condition.

DISCUSSION

Figure 2 Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. A 1.5 cm plate-shaped ulcerated hyperplastic lesion is seen in the middle esophagus, with a central depression, erosion, and slight bleeding.

ET is a rare form of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Primary ET is defined as involvement of the esophagus only but without the involvement of any other body site. Secondary ET is often caused by direct infiltration from adjacent mediastinal lymph nodes and some cases may be transmitted by lung or spinal infection or blood.Due to esophageal self-defense mechanisms such as mucosal protecting factors,stratified squamous epithelium, esophageal peristalsis, mucus, saliva, and erect posture, primary ET is extremely rare and secondary ET is more common. In this case,the patient was considered to have secondary ET complicated with ITB.

According to existing case reports[3-7], ET is more common in middle-aged and elderly women, but a minority of patients are young[8]. The onset of ET is often insidious, with few systemic manifestations of typical tuberculosis such as low fever,fatigue or night sweats. Dysphagia is the most common presentation, and is possibly related to factors such as lymph node mass compression, mediastinal fibrosis,esophageal ulcer, or decreased esophageal activity. In addition, some patients presented with swallowing pain, which may relate to ulcer lesions, and heartburn,swallowing cough, or other disorders[3]. Few patients presented with gastrointestinal bleeding, perforation, esophagotracheal fistula, aspiration pneumonia, or esophageal stenosis[4,8,9]. Our patient’s presentation was consistent with the characteristics of ET.

The most common area involved in ET is the middle third of the esophagus, due to the abundant lymphoid tissue in the region adjacent to the subcarina. ET is often classified by ulcerative or protruded lesions seen on endoscopy, which is easily misdiagnosed as esophageal leiomyoma or esophageal cancer. Ulcerative lesions,which are more common, are usually superficial ulcers of different sizes and irregular margins, often involving the mucosa and submucosa. A small number of patients may have deep ulcers, even penetrating the esophagus wall and leading to complications such as esophagobronchial or esophago-mediastinal fistula. Ulcerative lesions usually tend to self-heal, but as a result, the formation of fibrous tissue hyperplasia and scar may lead to esophageal stenosis and diverticulum. Protruded lesions often present as mucosal nodular bulges or submucosal masses, which may lead to esophageal stenosis or esophageal obstruction[3,4,10,11]. Our patient was initially presumed to have esophageal leiomyoma. ITB often involves the terminal ileum, ileocecal valve, and cecum. Characteristic endoscopic manifestations of ITB include a patulous ileocecal valve and rat-bite and transverse ulcers. These ulcers are usually characteristically shallow with an irregular geographic border just as in our case.

EUS assessment of morphological manifestation is a feasible method for the diagnosis of ET[4,12]. Initially, due to the infiltration of adjacent mediastinal lymphadenopathy, the esophageal wall may thicken or form a surface-destroyed intramural mass, accompanied by the destruction of the typical anatomical hierarchy structure of the esophageal wall. Subsequent morphology varies according to the different pathological stages of tuberculosis. Sometimes, multiple pathological changes may be found simultaneously in one lesion. Homogenous, hypoechoic areas correspond to proliferative lymphadenitis, which is characterized by lymphocyte infiltration and capillary proliferation in the early stages of the disease.Heterogeneous, iso-hypoechoic regions are associated with caseous necrosis or enlarged lymph nodes, which are fused, and due to membrane disruption in the middle stage of tubercular pathology. Unevenly distributed hyperechogenic strands and foci on EUS images represent fibrosis and calcification[3,10]. Our patient’s EUS showed a homogeneous hypoechoic lesion in the middle of the esophagus, with the destruction and fusion of the anatomical structure of the esophageal wall, and enlarged lymph nodes outside the lumen adjacent to the esophageal lesion. These manifestations are the diagnostic basis for secondary ET.

Figure 3 Endoscopic ultrasonography. A homogeneous hypoechoic lesion protrudes into the esophageal lumen,with disappearance and fusion of the mucosal layers, and 17.5 mm × 21.3 mm enlarged lymph nodes adjacent to the esophageal lesion.

Histopathologic features, including caseating granulomas and caseating necrosis,have been considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of tuberculosis. For both ET and ITB, histopathology for caseous necrosis, acid-fast bacilli or epithelioid granuloma is required for a final diagnosis. In the report of Puriet al[10], 84.5% of the patients with ET were diagnosed by pathology. Endoscopic mucosal biopsy and EUS-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) of the lymph nodes can provide important evidence for diagnosis. The acid-fast bacilli-positive rate is higher in EUS-FNA of the lymph nodes as compared to endoscopic ulcer biopsy. For patients, whose mucosal biopsies are inconclusive, a further EUS-FNA should be performed to confirm diagnosis. Some researchers have shown that combining these two methods can improve diagnostic efficiency[10]. In addition, Microbiological findings, including acidfast bacilli, TB-PCR, TB-culture and T-cell spot tuberculosis can also aid in diagnosis.

Imaging findings of ET are mostly nonspecific, including focal esophageal wall thickening, subcarinal mediastinal lymph node enlargement, ulcerated mucosa overlying the lesion, luminal stenosis, pseudotumor mass, sinus tract, and fistula.Enhanced computed tomography usually shows multiregional lymph nodes with clear margins, homogeneous or heterogeneous density, central low attenuation, or peripheral rim enhancement[3]. The combined imaging and laboratory results in our case established a diagnosis of secondary ET complicated with ITB.

Generally, patients with ET or ITB have a good clinical responses to ATT. Early detection, diagnosis, and treatment are conducive to the healing of lesions, and improve the prognosis for tuberculouss tracheoesophageal fistula[13]. Our patient responded well to ATT, which confirmed the diagnosis of ET complicated with ITB.After 2 mo of ATT, her clinical symptoms were markedly improved and repeated gastrointestinal endoscopy showed that an esophageal ulcer scar had formed.

It should be noted that ET patients complicated with pulmonary, bone, or other tuberculosis often have a poor prognosis. If medical treatment fails to close the fistula,surgery is required. Emergent surgery may be required in patients with arterial esophageal fistula complicated with acute hemorrhage. As for patients with esophageal stricture, endoscopic interventional therapy such as balloon dilatation or esophageal stent implantation can be performed[7-9]. In addition, the increase of drugresistant TB strains in recent years creates new challenges for effective ATT that require further research[14,15].

CONCLUSION

When dysphagia or odynophagia occurs in patients in high-risk areas for tuberculosis,ET should be considered. Differential diagnosis includes esophageal leiomyoma and esophageal cancer, and ET is also easily misdiagnosed as lymphoma, sarcoidosis, or esophageal Crohn’s disease. Misdiagnosis may lead to unnecessary surgery and delayed therapy. A comprehensive approach with multiple diagnostic tools should be utilized to increase the diagnostic yield[11]. For patients with suspected ET but pending a confirmed diagnosis, it may be wise to administer ATT while closely observing symptoms and endoscopic changes.

Figure 4 Pathologic biopsy of esophageal lesions. Hematoxylin-eosin staining, × 200 shows epithelial detachment and interstitial granulation tissue hyperplasia,under inflammatory exudation.

Figure 5 Colonoscopy. A: An irregular ulcer with a rat-bite border in the terminal ileum; B: A shallow ulcer with irregular border in the ascending colon.

Figure 6 Pathologic biopsy of the terminal ileal lesion. Hematoxylin-eosin staining × 200 reveals that the mucosa was in an acute inflammatory activity period of chronic inflammation, with decreasing or disappearing crypts in some areas, and some small focal granulomas, with caseous necrosis and surrounded by numerous lymphocytes.

World Journal of Clinical Cases2020年3期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2020年3期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Comprehensive review into the challenges of gastrointestinal tumors in the Gulf and Levant countries

- Can cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors convert inoperable breast cancer relapse to operability? A case report

- Ruptured splenic peliosis in a patient with no comorbidity: A case report

- Successful kidney transplantation from an expanded criteria donor with long-term extracorporeal membrane oxygenation treatment: A case report

- Boarding issue in a commercial flight for patients with cavitary pulmonary tuberculosis: A case report

- Cytomegalovirus ileo-pancolitis presenting as toxic megacolon in an immunocompetent patient: A case report