Successful kidney transplantation from an expanded criteria donor with long-term extracorporeal membrane oxygenation treatment: A case report

Hye Won Seo, Sua Lee, Byung Ha Chung, Chul Woo Yang, Division of Nephrology, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul 06591, South Korea

Hye Won Seo, Sua Lee, Byung Ha Chung, Chul Woo Yang, Transplant Research Center,Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul 06591, South Korea

Hwa Young Lee, Division of Nephrology, Department of Internal Medicine, Jeju National University Hospital, Jeju-do 63241, South Korea

Sun Cheol Park, Department of Surgery, Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, 222 Banpo-daero, Seoul 06591, South Korea

Tae Hyun Ban, Division of Nephrology, Department of Internal Medicine, Eunpyeong St.Mary’s Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Eunpyeong-gu,Seoul 03312, South Korea

Abstract

BACKGROUND

Due to a shortage of donor kidneys, many centers have utilized graft kidneys from brain-dead donors with expanded criteria. Kidney transplantation (KT)from donors on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) has been identified as a successful way of expanding donor pools. However, there are currently no guidelines or recommendations that guarantee successful KT from donors undergoing ECMO treatment. Therefore, acceptance of appropriate allografts from those donors is solely based on clinician decision.

CASE SUMMARY

We report a case of successful KT from a brain-dead donor supported by ECMO for the longest duration to date. A 69-year-old male received a KT from a 63-yearold brain-dead donor who had been on therapeutic ECMO treatment for the previous three weeks. The recipient experienced slow recovery of graft function after surgery but was discharged home on post-operative day 17 free from hemodialysis. Allograft function gradually improved thereafter and was comparatively acceptable up to the 12 mo follow-up, with serum creatinine level of 1.67 mg/dL.

CONCLUSION

This case suggests that donation even after long-term ECMO treatment could provide successful KT to suitable candidates.

Key words: Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; Kidney transplantation; Delayed graft function; Donor selection; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Shortage of donors is a major barrier to increasing the number of kidney transplants.To overcome this problem, many attempts have been made to utilize donor kidneys as efficiently as possible. One such attempt is to define expanded criteria donors(ECD) with respect to age, hypertension, renal function, and cause of death (Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network/United Network for Organ Sharing)[1,2].Although transplantations from ECD are increasing[1,3], successful donation of an allograft from donors on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) has been sporadically reported[4]. Unfortunately, the rate of delayed graft function (DGF) and early graft failure were higher in renal transplantation from ECMO-supplied donors than from standard criteria donors[4,5]. This is due in part to the paucity of data on donors with previous ECMO treatment and also to the lack of clear guidelines on acceptable donor information in terms of duration of ECMO treatment, renal function before nephrectomy, underlying disease, and age. Hence, it is important to develop acceptable criteria for kidney donations among patients on ECMO treatment and to select appropriate candidates for those kidneys.

We present a case of a 69-year-old male who received a graft kidney from a braindead donor supported by ECMO for therapeutic purposes for three weeks before transplantation.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 63-year-old male was transferred to our hospital for refractory heart failure,complaining of aggravating dyspnea and generalized edema.

History of present illness

Despite conventional therapy, the patient’s heart condition, for which initial echocardiography showed severe left ventricular dysfunction with an ejection fraction of 19%, worsened to cause cardio renal syndrome type 1. Eventually, he was placed on veno-arterial ECMO as a bridging therapy for heart transplantation. After 17 d, he abruptly developed a drowsy mentality and brain imaging showed a massive hemorrhage with brain stem herniation. Following diagnosis of brain death, the patient’s family decided to donate his organs.

History of past illness

The patient had been treated for ischemic heart failure for three years and for diabetes for four years. With an implantable cardioverter defibrillator inserted, his heart function remained at an ejection fraction of 25%. He was on oral hypoglycemic agents including metformin, dapagliflozin, and gliclazide and was in good control of his diabetes with a recent HbA1c of 5.2%. According to his past medical record, serum creatinine level was 0.83 mg/dL (0.7 to 1.3 mg/dL) without proteinuria.

Physical examination

On admission, the patient’s blood pressure was 88/50 mmHg, his heart rate was 100 bpm, respiratory rate was 22 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation in room air was 88%. Generalized edema with cool extremities was found, and pulmonary crackle and cardiac murmur were heard, suggestive of cardiogenic shock.

Laboratory examinations

On hospital day 0, acute kidney injury developed with increase in serum creatinine level to 2.58 mg/dL. However, this was ameliorated after ECMO initiation and remained around the upper level of the reference range after hospital day 6. In the meantime, urine output was preserved at well over 1000 mL per day. Finally, at the time of organ procurement, serum creatinine level was 1.35 mg/dL, and daily urine output was more than 2000 mL.

Imaging examinations

Brain computed tomography scan showed a massive hemorrhage on the brain stem with herniation (Figure 1A). Both kidneys were normal in size and shape in kidney ultrasound (Figure 1B).

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Given that the patient was older than 60 years, diabetic, and supported on therapeutic ECMO for the previous three weeks, he was considered a brain-dead donor meeting several expanded criteria. In addition, the kidney donor profile index (KDPI) and kidney donor risk index were estimated as 87% and 1.52, respectively.

TREATMENT

We provided information on kidney donor-related risk to the recipient 69-year-old male candidate in advance. He was under hemodialysis owing to diabetic nephropathy and had been waiting for kidney transplantation (KT) for nine years.Without any hypoglycemic agent, he was in good control of his diabetes with an HbA1c of 5.6%. Other medical history included atrial fibrillation and bronchiectasis due to previous tuberculosis. The immunologic profile was HLA mismatch number 5 with negative results of the crossmatch test and panel reactive antibody. Finally, he chose to accept the graft kidney rather than staying on the waiting list.

On the other hand, the opposite side of donor kidney was transplanted to a 59-year-old male, with delivery of information on donor-related risk before the surgery.He underwent peritoneal dialysis for 12 years due to unknown primary renal disease,and was treated for status epilepticus three years ago and cerebral infarction a year earlier. The immunologic profile was HLA mismatch number 4 with negative results of crossmatch test and panel reactive antibody.

The cold ischemic time of KT was 109 min and 123 min, respectively, and there were no acute complications during the perioperative period. The immunosuppressive agents administered were rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin 1.25 mg/kg/d for five days as an induction therapy and corticosteroid, tacrolimus, and mycophenolic acid as a triple regimen for maintenance therapy.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Figure 1 Imaging examinations. A: Brain computed tomography scan shows acute brain hemorrhage with brain stem compression and herniation; B: Kidney ultrasound shows both kidneys normal in size (right kidney: 11.9 cm, left kidney: 12.5 cm) and echogenicity.

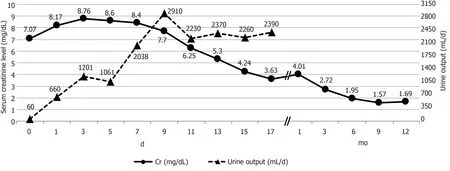

Allograft function of the 69-year-old male recipient showed a slow recovery after transplantation. Serum creatinine and urea nitrogen levels dropped gradually throughout the post-operative period from 8.7 to 3.63 mg/dL and 120.9 to 70.8 mg/dL, respectively (Figure 2). Meanwhile, urine volume was more than 1000 mL per day, and no uremic symptoms were observed. Finally, the patient was discharged home on post-operative day (POD) 17, free from hemodialysis.

An indication biopsy performed to find a cause of delayed recovery revealed diabetic nephropathy and calcineurin inhibitor toxicity without acute rejection. The patient contracted fungal pneumonia with acute kidney injury twice within three months after KT but recovered without complication. Thereafter, graft function gradually improved, with serum creatinine level decreasing to 1.67 mg/dL at the 12 mo follow-up (Figure 2).

The other recipient also exhibited a slow recovery of allograft function. Urine volume was gradually increased with decrease in serum creatinine from 15.8 to 8.62 mg/dL. Allograft biopsy was performed owing to slow recovery of renal function on POD 7. The pathology showed diabetic nephropathy and calcineurin inhibitor toxicity without acute rejection, consistent with that of the opposite allograft. However,uncontrolled bleeding at renal artery anastomosis site was started on POD 10. Despite emergent allograft nephrectomy, bleeding was continued to cause multi-organ failure and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Finally, he passed away on POD 16.

DISCUSSION

The importance of this case is the achievement of successful graft function until 12 mo after transplantation from a brain-dead donor supported with therapeutic ECMO treatment for three weeks before donation. Despite slow recovery, allograft function was acceptable up to the last follow-up. This case suggests that ECD kidneys, even after a donor has been under ECMO for a relatively long duration, can provide a successful clinical outcome in a well-selected recipient.

ECD kidneys are currently the best options to solve the donor shortage; however,poor graft function and long-term survival are major concerns. Even though the number of KTs from ECD is increasing, data regarding clinical outcomes of KT recipients from ECMO-supported donors are very limited. Furthermore, there are no clear guidelines or recommendations on whether to accept ECMO donor kidneys and to which candidates to allocate them.

According to previous reports, more than 30% of patients receiving ECMO may experience acute kidney injury[6]. Given the increased risk of acute inflammatory and immune-mediated processes, ischemic injury, and coagulation abnormalities with ECMO use[6,7], the rates of DGF and early graft failure were reported to be higher in KT recipients from ECMO donors than in those from non-ECMO donors[8-10].Therefore, a longer duration of ECMO increases the risk of DGF[10]. Nevertheless,multiple recently published studies have demonstrated that use of ECMO donors had no impact on short- or long-term graft function or survival[4,5,9,11].

A study in which the graft outcomes using ECD kidneys were analyzed based on histologic findings and donor renal function at procurement confirmed favorable long-term patient and graft survival rates[2]. Moreover, a retrospective analysis found that favorable outcomes from ECD kidneys were associated with donor age, donor urine volume on the day before nephrectomy, and total ischemic time[12]. Therefore,without established guidelines, physicians may consider these factors as well as kidney donor profile index and kidney donor risk index to evaluate the quality of ECD kidneys and decide whether to accept them. Overall, appropriate acceptance and allocation of ECD kidneys from ECMO-supported donors are critical to optimize organ utilization and achieve successful KT.

Figure 2 Allograft function after kidney transplantation.

Diabetic donor kidneys are associated with increased risk of graft failure and mortality compared with non-diabetic donor kidneys[13]. However, some studies have demonstrated that those impacts were mitigated in long-term outcomes, and that they provided survival benefits over remaining on the transplant waitlist[13]. Given that early diabetic changes in grafts may improve after KT with good glycemic control,kidneys from donors who are not treated with insulin, and who show microalbuminuria below 30 mg/g creatinine and HbA1c below 6.5% are utilized for transplantation in some centers[14]. Likewise, our donor had a short duration of diabetes (less than 5 years), good glycemic control with an HbA1c of 5.2%, and no proteinuria on oral hypoglycemic agents. Still, no standard is available by which the degree of diabetic injury in donor kidneys is considered acceptable in terms of proteinuria, oral hypoglycemic agent, duration of diabetes, and HbA1c.

The limitation of the present case is that no procurement biopsy was performed.However, current studies lack evidence that procurement biopsy findings can predict graft outcome due to variabilities in biopsy techniques and sample processing and inconsistencies in histological evaluation and interpretation[1,15]. Overall, routine use of biopsy is not recommended and its importance is less weighted than clinical parameters[2]. Next, the changes in the opposite allograft function was not confirmed due to death of the recipient. Nonetheless, up until the bleeding started, the allograft function gradually improved with increase in urine volume and decrease in serum creatinine, and the pathologic results from both recipients were the same without rejection or ischemic injury.

Consistent with recent reports[4,5,9,11]demonstrating that ECMO donors had no detrimental impact on long-term graft function and survival, this case showed favorable allograft function until the last follow-up even after long duration of ECMO treatment in the donor. Moreover, as suggested by some literature[2,12], our donor had several clinical features that could have confirmed such a favorable graft outcome. In other words, the donor renal function was acceptable as reflected by urine volume and serum creatinine at procurement despite the lack of pathologic information of the donor kidneys. Besides, good glycemic control over a short diabetic period was also in line with the existing literature[14]. In conclusion, our case suggests that donors supported by ECMO over a long duration with acceptable renal function and wellcontrolled diabetes before nephrectomy may lead to successful outcomes for carefully selected recipients.

CONCLUSION

Even with increased use of ECD kidneys, limited data on clinical outcomes after KTs from ECMO donors and lack of guidelines on acceptance of these marginal kidneys are of major concern. For those reasons, acceptance of graft kidneys and their resulting KT outcomes largely depend on decisions from clinicians. Therefore, in the future, this case can help clinicians to decide whether to use kidneys from candidates supported by ECMO over a long duration and how to find suitable recipients. This is a rare case of successful KT from such an old donor with diabetes who was on therapeutic ECMO supply for a long duration, highlighting the potential role of ECMO support in renal transplantation. Further research on long-term graft outcomes from ECMO-supported donors and development of guidelines are necessary.

World Journal of Clinical Cases2020年3期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2020年3期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Comprehensive review into the challenges of gastrointestinal tumors in the Gulf and Levant countries

- Can cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors convert inoperable breast cancer relapse to operability? A case report

- Ruptured splenic peliosis in a patient with no comorbidity: A case report

- Boarding issue in a commercial flight for patients with cavitary pulmonary tuberculosis: A case report

- Cytomegalovirus ileo-pancolitis presenting as toxic megacolon in an immunocompetent patient: A case report

- Camrelizumab (SHR-1210) leading to reactive capillary hemangioma in the gingiva: A case report