Bone disease in chronic pancreatitis

Awais Ahmed, Aman Deep, Darshan J Kothari, Sunil G Sheth

Awais Ahmed, Aman Deep, Sunil G Sheth, Division of Gastroenterology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA 02215, United States

Darshan J Kothari, Division of Gastroenterology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham,NC 27710, United States

Abstract

Key words: Bone disease;Osteopenia;Osteoporosis;Fracture risk;Chronic pancreatitis;Malabsorption

INTRODUCTION

Osteoporosis affects an estimated 75 million people across the United States, Europe and Japan[1].Globally, 8.9 million osteoporotic fractures occur annually and are associated with increased morbidity and mortality[2].Screening programs for prevention of osteoporotic fractures are cost-effective in reducing the incidence of new fractures, thus highlighting the importance of identifying risk factors that predispose to bone disease[3,4].Bone health is maintained by a complex balance between bone formation and resorption, modulated by endocrine, immune and digestive organ systems, which in turn are affected by individual risk factors including age, gender, body mass index (BMI), nutritional status, tobacco and alcohol use, and chronic steroid use[5,6].Chronic inflammatory conditions, especially those affecting the gastrointestinal tract, further increase the risk for bone disease,disrupting normal organ function as evidenced by the increased prevalence in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease and chronic liver disease[7-11].Chronic pancreatitis (CP) is a progressive and irreversible inflammatory condition,which results in exocrine and endocrine dysfunction.Thus, patients with CP are increasingly being recognized to be at higher risk for bone disease[12].Our review summarizes the risk factors and prevalence of bone disease in CP.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The prevalence of osteopenia in CP has been reported in studies to be anywhere between 18%-71.4%, with varying risk factors as previously described[13-15].In a metaanalysis by Dugganet al[14]40% of the pooled patient population were found to have osteopenia.Furthermore, 25% were found to have osteoporosis.Similarly, in the multicenter European study, 42.18% of patients had osteopenia while 21.8% had osteoporosis[13].In these studies, the patient population comprised mainly of adult non menopausal patients, with variable etiologies of CP.Common secondary risk factors for bone disease included tobacco and alcohol use, exocrine insufficiency and BMI.

RISK FACTORS

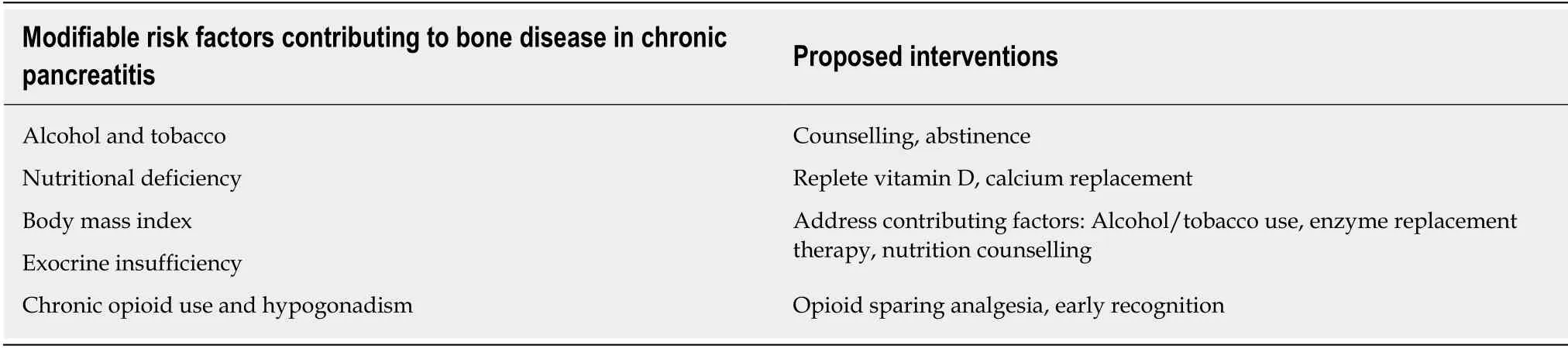

While the precise pathophysiology and mechanistic pathway of bone disease in CP is not well defined, presence of bone disease in other malabsorptive conditions of the gut, such as inflammatory bowel disease and celiac disease, has helped advance our understanding of risk factors and prevalence in CP[6-8,10].Specifically, malabsorption of nutrients (Vitamin D and calcium), low bone mass, alcohol use, smoking and circulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines contribute to a decline in bone health in these patients, all of which can be seen in patients with CP (Table 1).Consequently,several studies have examined the risk factors and prevalence of bone disease in CP.

Chronic inflammation

Proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) increase bone turnover by perpetuating osteoclastic activity[16-18].Similar associations have been made with systemic inflammation marker C-reactive protein (CRP) and bone disease[19,20].This association of inflammation with low bone mineral density (BMD) and high bone turnover was demonstrated in patients with CP by Dugganet al[21]in 2015.In this study, patients with CP had an elevated mean high-sensitivity CRP [3.15 (1.3-7.75)vs0.9 (0.5-2.15),P< 0.0013] and IL-6 [5.61vs2.58 (-0.06-1.82),P= 0.06], when compared to controls although the latter did not reach statistical significance.Both CRP and IL-6 were associated with low BMD.Notably, the study also analyzed markers of bone turnover, as a measure of bone metabolism.Compared to controls, markers of osteoblastic activity (procollagen 1 amino-terminal propeptide and osteocalcin) and osteoclastic activity (carboxy-terminal telopeptide of type 1 collagen) were significantly elevated in CP.Thus, demonstrating increased bone remodeling in the inflammatory state of CP.

BMI

In the general population, lower BMI is a risk factor for bone fracture.Patients with CP are at risk for being malnourished and thus may have a lower BMI, due to exocrine insufficiency, malabsorption, and ongoing alcohol and tobacco use[22-25].Stiglianoet al[13]showed in their study that mean BMI was lower in patients with CP and either osteopenia or osteoporosis (24 ± 3 and 22 ± 3, respectively)vscontrols (25 ±4) for both males and females (P= 0.001).These findings confirmed data from prior studies[26-29].

Table 1 Risk factors

Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency

Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI) results from progressive destruction of acinar and ductal cells, leading to reduction in pancreatic enzyme and bicarbonate secretion and ultimately maldigestion and malabsorption.If left untreated, patients can present with steatorrhea, weight loss and, nutrient deficiency[29,30].Although imperfect,diagnosis of EPI typically requires stool collection for fat quantification and/or fecal elastase concentration.Studies have evaluated EPI by measuring fecal elastase concentration or 72 h-stool fat quantification as a risk factor for developing osteopenia or osteoporosis, and have produced conflicting results[14].In a multicenter, crosssectional European study, Stiglianoet al[13]used fecal elastase levels as a means of diagnosis of EPI, and did not find a correlation between presence of EPI and osteopenia or osteoporosis.Interestingly however, Haaset al[15], in their prospective cohort study of 50 male patients, noted that patients with EPI receiving pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy had higher bone density scores compared to those who were not taking pancreatic enzymes ( -0.80 ± 0.6vs-1.51 ± 0.55,P< 0.05).Despite the discrepancy, screening for and treating EPI to prevent bone disease is recommended by pancreas experts[31-33].

Nutritional deficiency

The role of vitamin D, calcium and phosphorus is well established in bone homeostasis.Adequate vitamin D is essential for efficient and maximal absorption of intestinal calcium and phosphorus[34-37].Vitamin D deficiency causes decreased intestinal calcium absorption which can lead to secondary hyperparathyroidism,which in turn stimulates osteoclastic demineralization of bone, resulting in osteopenia and osteoporosis.With primary sources of Vitamin D being sunlight exposure and diet, patients with CP are a particularly vulnerable group, as they are susceptible to malabsorption of fat soluble vitamins in EPI.However, studies to date have not consistently shown an association between vitamin D and low BMD or as a predictor of bone disease[13,27,28-29].In one meta-analysis of nine studies, Hoogenboomet al[38]showed that while the pooled prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in CP patients was 65%, it was not significantly different to healthy controls, with an odds ratio of 1.14(0.70-1.85,P> 0.05).Conversely, Dugganet al[21], demonstrated a higher prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in CP compared to controls (P= 0.026), which independently predicted BMD.This finding was noted in the setting of a strong association with smoking and chronic inflammation, which could suggest that vitamin D deficiency may serve as a co-factor for developing bone disease.Thus, the true utility of measuring vitamin D levels in CP remains unclear.Further studies are needed to elucidate whether it accurately aids in the assessment of bone health in CP.

Vitamin K is another fat-soluble nutrient which plays a possible role in bone metabolism as a cofactor in several mechanisms, including gamma-carboxylation of osteocalcinin, inhibiting osteoclastogenesis and promoting osteoblastosis[39].Vitamin K is deficient in 32%-63% of patients with CP[13,40].In their P-Bone study, Stiglianoet al[13]showed that serum vitamin K deficiency (< 0.2 ng/mL) was present in 32% of 211 CP patients studied, and associated with a higher risk of osteoporosis in male patients(OR 5.28;95%CI:1.31-2.14;P= 0.01).As this is the only study to date to have examined association of vitamin K deficiency in CP, further investigation is necessary to clarify its role in bone disease of CP.Currently, there are no recommendations to test for vitamin K deficiency in patients with CP, to help prevent bone disease.

Alcohol

Alcohol is a risk factor for osteoporosis in the general population, as it causes malnutrition and low BMI[41].Several studies report an association between alcohol use in CP patients and fracture risk.In a large Veteran’s Administration study Munigalaet al[42], compared two cohorts consisting of CP patients and controls(without history of bone disease or CP), with a primary outcome of fractures at any site.A higher prevalence for fractures was seen in patients with CP and alcohol use compared to the control cohort (OR = 2.30).Similar findings were reported in a retrospective Danish registry study, with an increased risk of fractures in patients with alcohol induced CP compared to non-alcohol CP (HR 2.0vs1.5;P< 0.0001)[43].Interestingly, a similar association has not been directly found between alcohol use in CP and osteopenia or osteoporosis[36,44].Alcohol cessation remains a priority recommendation by pancreas experts in patients with CP as a measure to reduce fracture risk[31-33].

Tobacco

Tobacco consumption has been associated with osteoporosis and fractures in the general population, irrespective of gender, and is also an independent risk factor for developing osteoporosis[45,46].A few studies have analyzed the association in CP.In a cross sectional, match-controlled study, Dugganet al[28]reported low bone density scores among patients with the highest tobacco use.In a later study, the same group reported a strong association between heavy smoking and low vitamin D levels[21].Munigalaet al[42]also reported increased prevalence of fractures in smokers compared to non-smokers (OR = 1.97).Thus tobacco cessation is also recommended by pancreas experts to reduce the risk of bone disease in CP.

Hypogonadism and opioid use

A prospective, observational study by Guptaet al[47]demonstrated that up to 27% of non-menopausal patients with low BMD had hypogonadism.Chronic opioid use,suppresses the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis as well as the hypothalamicpituitary-adrenal-axis resulting in opioid induced androgen deficiency which may predispose to osteopenia and osteoporosis[48].There are no studies to determine if sex hormone replacement therapy in patients with CP has any benefits on bone density.In addition to opioids, CP patients should be queried about use of other medications that may cause bone loss such as steroids.

Patients with multiple risk factors

Patients with CP typically do not have isolated risk factors for bone disease;rather their health is compromised by multiple issues, all of which can contribute to the development of bone disease.In one study by Haaset al[15], higher bone density scores measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) were noted in patients with EPI who had received pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy.Hence it is possible that early correction of EPI in these patients can potentially prevent progression of bone disease.Additionally, population-based data that higher BMI is associated with decreased risk of osteoporosis was also seen in P-Bone trial by Stigliano (0.84 per unit;0.76-0.94;P= 0.001), which further strengthens the argument that early diagnosis of malabsorption and EPI can be an effective strategy in reducing risk of bone disease in CP patients[13].Further investigation with randomized trials would be warranted for more conclusive evidence to support this finding.

FRACTURE RISK

Fragility or low trauma fracture is the most consequential outcome of osteoporosis and is of particular concern for patients with CP.In 2010, a retrospective study examining the prevalence of fractures in patients with CP, noted that patients with CP have a higher risk of fracture when compared to those without CP and also patients with high risk gastrointestinal illnesses (i.e., Crohn’s disease) (P< 0.0001)[49].These findings were replicated in subsequent studies.In 2014 Banget al[43]reported a fracture incidence rate of 42.9 per 1000 person years in CPvs16.0 in the control group.In another retrospective analysis of the Veteran’s Administration database, a cohort of 3257 predominantly male patients was compared to a control group without CP[42].They reported a higher OR of all fractures in CP (2.35;95%CI:2.00-2.77;P< 0.0001)with the highest prevalence of fractures noted in CP patients with a history of alcohol use, smoking or both.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Bone disease in CP can be attributed to several risk factors which act synergistically in propagating abnormal bone metabolism and increase the risk of fractures.Therefore,expert groups in the United States and also European society guidelines recommend instituting proactive measures in identifying at-risk patients, with the goal of addressing modifiable risk factors and also to reduce the risk of fractures[31-33].In the United States, a multi-disciplinary CP working group recommended that all patients should have routine annual screening for nutrient deficiency irrespective of EPI[31].If a diagnosis of EPI is determined, they also recommend supplementation of fat-soluble vitamins and nutrients.Furthermore, they recommend a baseline screening DXA scan in these patients with subsequent screening based on assessment of collective risk factors for fracture.European societal guidelines recommend that a baseline DXA scan should be extended to all patients with CP with follow up scans every 2 years if evidence for osteopenia is found.In addition, initiation of Vitamin D and calcium supplementation can help treat and prevent osteopenia, osteoporosis and lower the risk of fracture, thus patients with established bone disease should be thoroughly evaluated for appropriate therapies by an endocrinologist.

World Journal of Clinical Cases2020年9期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2020年9期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Nutrition management in acute pancreatitis:Clinical practice consideration

- Role of microRNAs in the predisposition to gastrointestinal malignancies

- Recurrent anal fistulas:When, why, and how to manage?

- Removal of biofilm is essential for long-term ventilation tube retention

- Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin does not predict acute kidney injury in heart failure

- Prognosis factors of advanced gastric cancer according to sex and age