Antimony removal from wastewater by sulfate-reducing bacteria in a bench-scale upflow anaerobic packed-bed reactor

· · ·

Abstract The objective of this research was to study the precipitation of Sb and the stability of Sb2S3 during treatment of synthetic Sb(V) wastewater by sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB). We investigated the transformation and precipitation of Sb, as well as the re-dissolution of Sb2S3 under different pH and carbon sources.The results showed that the precipitation of aqueous Sb and the re-dissolution of Sb2S3 depend on the conversion between Sb(III)-S(-II)complexes and Sb2S3 precipitates. These processes were highly pH-dependent, and a decrease in pH enhanced reduction of Sb(V) and precipitation of Sb2S3 were observed. The newly formed Sb2S3 was found to be unstable and could re-dissolve through complexation with H2S due to the increase in pH. When pH decreased to approximately 6.5, Sb was almost completely transformed into Sb2S3 precipitates, and the Sb2S3 precipitates were relatively stable.Compared with lactate as a carbon source,ethanol resulted in a comparable H2S yield and a relatively low pH and was,therefore,more conducive to the removal of Sb(V). The results of this study suggest that when removing Sb(V) in wastewater by SRB, it is important to control the pH at a relatively low level.

Keywords Antimony · Removal · Mechanism ·Wastewater · Sulfate-reducing bacteria

1 Introduction

Antimony (Sb) is a toxic element to living organisms and can accumulate in animals and plants. It may even cause cancer after entering the human body. Therefore, Sb is listed as a priority pollutant by the US Environmental Protection Agency and the European Union (Filella et al.2002a; He 2007).

Sb has wide industrial applications, such as in flame retardants, batteries, plastics, paints, glass, and alloys,leading to a huge demand for Sb resources in the world(Filella et al. 2002a; Mariussen et al. 2012). However,severe Sb pollution can occur during the exploitation of Sb minerals (Wilson et al. 2010; Wu et al. 2011). This situation is particularly prominent in China, where approximately 84% of the Sb in the world is produced (He et al.2012). In world’s largest antimony mine, Xikuangshan, in Hunan Province, the Sb concentration in the percolating water of a tailing pile was as high as 38.3 mg L-1(Guo et al. 2018). In the Banpo Sb mine in Dushan County,Guizhou Province, China, the Sb concentration in the pore water of mill tailing slurry and adit water were as high as 7.9 and 1.3 mg L-1,respectively.The introduction of such Sb-polluted wastewaters to the surrounding water bodies and soil can degrade environmental quality and damage the ecosystem (Flynn et al. 2003; He 2007).

Currently, traditional physicochemical methods (e.g.,precipitation and adsorption) are used in the treatment of Sb-containing wastewaters (Guo et al. 2009; Kang et al.2003; Lee et al. 2018). However, these methods often require high costs and high energy consumption (Wakao et al. 1979). The biological sulfide precipitation method uses sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) to reduce SO42-and produce H2S. Heavy metals can be removed when they form sulfide precipitates with H2S. Due to the advantages of low costs and the high removal of heavy metals, this method has been widely investigated in the treatment of wastewaters containing Pb(II), Zn(II), Cu(II), Ni(II), and Fe(II)(Jong and Parry 2003;Alvarez et al.2007;Kaksonen et al.2011;Kieu et al.2011).As a metalloid,Sb is different from heavy metals in many aspects. In the surface water environment, Sb generally exists as(Sb(V))(Filella et al. 2009; Wilson et al. 2010), which needs to be reduced to H3SbO3(Sb(III)) before forming a sulfide precipitate (stibnite, Sb2S3). In addition, Sb can form Sb(III)-S(-II) complexes (e.g., Sb2S42-and HSb2S4–) in sulfidewater systems (Krupp 1988; Filella et al. 2002b; Planer-Friedrich and Scheinost 2011). These characteristics may make the behavior of Sb in treatment by SRB complicated.Recently, some batch-experiment studies have demonstrated the feasibility of Sb removal by SRB and proposed that Sb(V) in wastewater is first reduced to Sb(III) and subsequently precipitated as Sb2S3(Wang et al. 2013;Zhang et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2018). However, the transformation of Sb species in a sulfidic system may not only result in the formation of Sb2S3precipitates but also significantly affect the stability of Sb2S3through complexation. So far, these considerations have not been well addressed. Lactate has been widely applied in lab-scale experiments, but its large-scale application may be limited due to its high operating costs (Kaksonen et al. 2003;Pagnanelli et al. 2012). Ethanol is low in cost compared with lactate (Zhang and Wang 2013). Therefore, a feasibility study on ethanol will help decrease the cost. Moreover, the effect of the products of carbon source oxidation by SRB on Sb removal has not been extensively studied.

In this study, Sb(V) wastewater was treated by SRB in an upflow bioreactor to examine the transformation of Sb species, with a particular focus on the formation and redissolution of the Sb2S3precipitates triggered by changes in pH. In addition, the feasibility of replacing lactate with the more economical ethanol as the carbon source was investigated.

2 Materials and methods

High-purity deionized water (HPW) (resistivity:18.2 MΩ cm) was prepared with a Milli-Q system (Millipore, Bedford, USA) and was used throughout the experiments. Potassium hexahydroxoantimonate (KSb(OH)6,99% purity) was purchased from Fluka Inc., Steinheim,Germany. All other chemicals were analytical grade.

The medium used for bacterial growth was modified Postgate’s medium B (Postgate 1984) (in g L-1): K2HPO40.5, NH4Cl 1.0, CaCl2·6H2O 0.1, MgSO4·7H2O 2.0, Na2-SO41.0,sodium lactate 3.5,yeast extract 1.0,ascorbic acid 0.1. When ethanol was used as the carbon source, the lactate in the medium was replaced by an equimolar amount of ethanol.

Synthetic Sb(V) wastewater was used in the treatment experiment. Given to the Sb concentration (1.3 and 7.9 mg L-1)in wastewater from antimony mining areas in China(see Introduction),we set the Sb concentration of the synthetic wastewater to 5 mg L-1. KSb(OH)6was first used to prepare a 500 mg L-1Sb(V) stock solution. Then,an appropriate amount of the stock solution was added into the modified Postgate’s medium B, and the pH was adjusted with 2 M HCl or NaOH to obtain synthetic wastewater containing 5 mg L-1Sb(V) with different pH values. When preparing the synthetic wastewater, yeast extract and ascorbic acid were not included in the modified Postgate’s B medium to avoid potential reduction by these components.

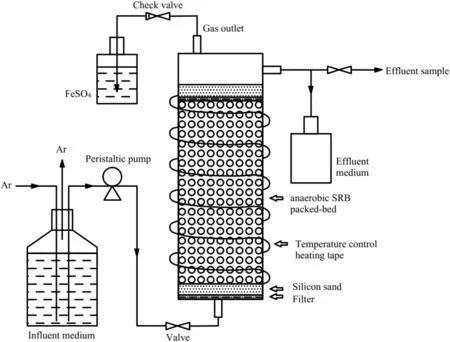

2.1 Reactor

The bioreactor was a closed cylinder made of polyvinyl chloride(PVC)with an inner diameter of 100 mm,a height of 300 mm and a volume of 2.35 L (working volume: 1.1 L) (Fig. 1). An inlet and an outlet were located at the bottom and the top, respectively. After the bottom was covered with a layer (thickness: ca. 5 mm) of water-filtering quartz cotton, the reactor was filled with ceramsite(size: 2–3 mm; porosity: 0.5) as a biofilm carrier (height:200 mm).The ceramsite was rinsed with HPW before use.

2.2 Experimental procedures

The bacteria used in the experiments were an SRB consortium previously enriched in the laboratory. The consortium contained Clostridium sp., Escherichia coli, and Ruminococcaceae. Among these bacteria, Clostridium sp.has been previously proven to be able to reduce sulfate(Liu et al. 2018).

First, 1000 mL of modified Postgate’s medium B was added to the bioreactor. The air in the remaining space of the reactor was purged with nitrogen (99.9% purity) for 0.5 h. The reactor was heated with electric heating tape,and the temperature of the internal liquid was controlled at 30 ± 2 °C (this temperature was maintained during the subsequent Sb(V)wastewater treatment and the precipitate leaching experiment). Next, a total of 100 mL of the SRB consortium culture was injected into the medium in the reactor and mixed thoroughly;then,the reactor was closed,and the preincubation of SRB started (day 0). Three days later, the modified Postgate’s medium B was pumped into the reactor from the bottom inlet (flow rate:0.76 mL min-1, hydraulic residence time: 24 h). Between days 1 and 30,a small amount of FeSO4(0.1 mg L-1)wasadded to the influent solution because Fe(II)can accelerate microbial growth and promote biofilm formation (Zhang et al. 2008). Between days 30 and 45, a microbial coating appeared on the ceramsite surface,and the odor of H2S was obvious in the effluent. In this period, the redox potential(Eh)of the solution in the reactor was- 281.6 ± 6.5 mV,and the H2S concentration was 143.9 ± 2.1 mg L-1,indicating that the SRB grew well and the solution was in a strong reducing state.

Fig. 1 A schematic diagram of the upflow anaerobic packed bed reactor setup used in this study

The treatment of Sb(V) wastewater started when the influent solution was replaced with synthetic Sb(V) wastewater on day 45. Two carbon sources, lactate and ethanol,were used in the treatment,and the influent pH was 7, 5, 3, and 9 at different periods (Fig. 2). The treatment experiment ended on day 198.

After the treatment experiment, an Sb-free medium solution (with ethanol as the carbon source) was quickly pumped(2.28 mL min-1)into the reactor to rapidly reduce the residual aqueous Sb in the reactor.The total Sb(Sb(T))concentration in the effluent after one day was less than 0.22 mg L-1. On day 200, the experiment examining the leaching of the precipitates in the reactor started, and the influent flow was adjusted to 0.76 mL min-1. The influent pH was set to neutral (pH 7), acidic (pH 3), and alkaline(pH 9 and 10) in different periods (Fig. 2). The leaching experiment ended on day 265.

2.3 Sample collection and pretreatment

For both the Sb(V) wastewater treatment experiment and the precipitate-leaching experiment, effluent was sampled at the outlet of the reactor on the first,second and third day after switching to a new influent pH(or carbon source)and every 2 days thereafter until the influent pH (or carbon source) was changed. Ultimately, 92 and 35 samples were collected during the Sb(V) wastewater treatment experiment and the precipitate-leaching experiment,respectively.After sampling, the effluent was introduced into a ferrous sulfate solution to prevent secondary pollution caused by sulfide.Each effluent sample was divided into two portions,one of which was syringe-filtered (0.45-μm pore-size nitrocellulose filter). The unfiltered portion was immediately used for measurement of pH, Eh, and alkalinity. The filtered portion was further divided into sub-portions for the determination of dissolved sulfate,dissolved sulfide,Sb(T),and Sb(III).

During the treatment of Sb(V) wastewater, a small fraction of the precipitates were collected from the bottom of the bioreactor under a flow of nitrogen, gently washed with nitrogen-purged HPW three times, and then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min in a benchtop centrifuge.The precipitates were freeze-dried for 24 h in a vacuum freeze dryer (Model FD-18, Detianyou Technologies,Beijing, China) and then stored in a glove box under a nitrogen atmosphere prior to use.

Fig. 2 Variations in the pH and carbon source of the influent solution in Sb(V) wastewater treatment and the precipitate leaching experiment(The carbon source is expressed as a percentage; 100% carbon source = 0.03 mol L-1)

The precipitate samples were subjected to the sequential chemical extraction of Sb following a method (Table 1)modified from Tessier et al. (1979) and Fu et al. (2016).The extraction was carried out in an anaerobic glove box.

2.4 Analyses

The pH and Eh of the effluent samples were immediately measured with a Denver UB-7 pH meter and a redox potential meter (TOA-DKK, Japan), respectively. Total alkalinity was analyzed by titrating unfiltered samples with 0.02 M HCl to pH 4.5 according to the standard method SFS-EN ISO 9963-1 (SFS 1996). The dissolved sulfide concentration was measured immediately after filtration using the methylene blue method (Greenberg et al. 1992)with a UV–Vis spectrophotometer. Dissolved sulfate was measured employing the turbidimetric method using a standard method, in which the sulfate is precipitated with barium chloride to form a suspension of barium sulfate(APHA 1998). The concentrations of Sb(T) were analyzed using a method modified from Zhang et al. (2016).Ascorbic acid (10 g L-1) and thiourea (10 g L-1) were mixed with the collected samples to reduce pentavalent Sb to trivalent species and to mask the interference of metals,and then the concentration of Sb(T) was determined by hydride generation-atomic fluorescence spectrometry(HGAFS) (AFS-2202E, Haiguang Instruments Corp., Beijing,China). For the analysis of Sb(III), citric acid (1 g L-1)was added to mask Sb(V) signal (Fuentes et al. 2003), and the concentration of Sb(III) was then determined. The Sb(V) concentration was calculated as the difference between the Sb(T) and Sb(III) concentrations.

The morphology and chemical composition of the precipitates were examined by scanning electron microscopy coupled with an energy dispersive spectrometer (SEM–EDS, model JSM-6460LV, JEOL, Japan). The mineralogical composition of the precipitates was analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) (D-MAX 2200, Rigaku Co., Japan).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Variation in Eh, pH, alkalinity, and sulfide

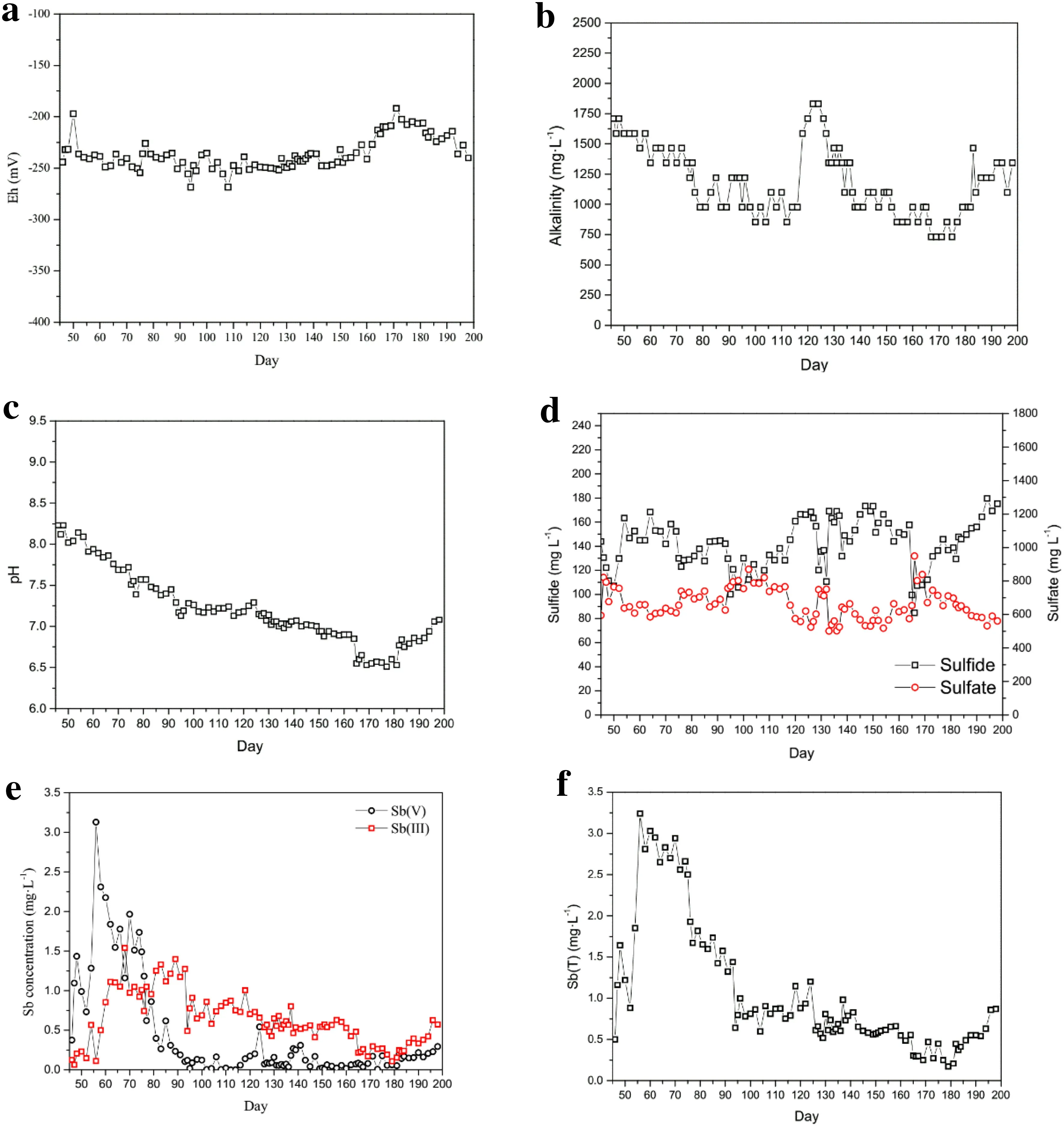

The Eh, alkalinity (expressed as HCO3-concentration),and pH of the effluent from the Sb(V)wastewater treatment experiment (days 45–198) are shown in Fig. 3. The Eh ranged from - 191.8 to - 244 mV (Fig. 3a), indicating stable reducing conditions.

The alkalinity and pH of the effluents in the treatment stages with different influent pH values are shown in Table 2. When the influent pH was the same, the use ofethanol as the carbon source resulted in a lower HCO3-concentration and a lower pH in the treatment solution than the use of lactate. This difference was possibly related to the oxidation mechanisms of the two carbon sources(Kaksonen et al. 2003; Pagnanelli et al. 2012).

Table 1 Procedure of the sequential chemical extraction of the precipitates

Fig. 3 Variations in parameters in Sb(V) wastewater treatment [a Eh; b alkalinity; c pH; d aqueous sulfide and sulfate; e Sb(V) and Sb(III);f Sb(T)]

Table 2 HCO3-concentrations and pH values in different stages

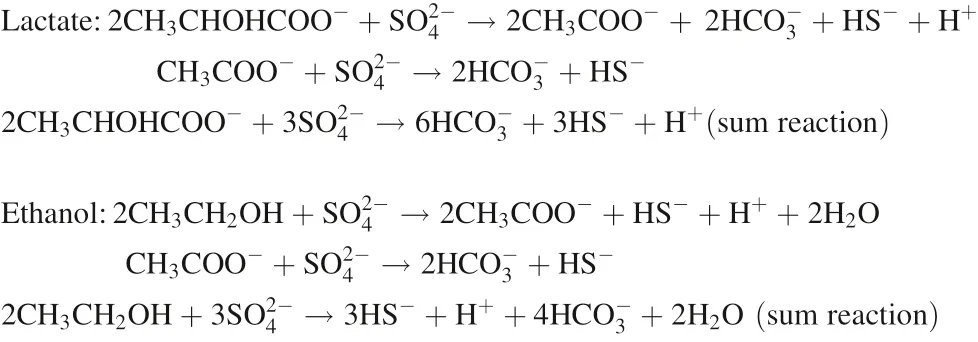

HCO3-is produced in two steps in the oxidation of lactate but only produced in one step in the oxidation of ethanol.Thus,the production of HCO3-in the oxidation of lactate is theoretically 1.5-fold that in the oxidation of an equivalent amount of ethanol. The production of HCO3-was assessed based on the HCO3-concentration when the influent was neutral because HCO3-could not react with acid in the influent. Regarding the oxidation of lactate and ethanol when the influent pH was 7, the average HCO3-production was 1502 and 1057 mg L-1(Table 2), respectively, and a molar ratio of 1.42 was obtained. This result agrees well with the theoretic ratio of 1.5, lending support to the oxidation mechanism above. It was also postulated that lactate and ethanol would exhibit similar oxidation rates, which was further supported by the similar yield of H2S (see below). Moreover, since the HCO3-in SRB system is the most important factor affecting the pH(Dvorak et al. 1992; Kousi et al. 2011), the use of ethanol as the carbon source resulted in a lower pH than that obtained with the use of lactate(Table 2).Different carbon sources lead to slight differences in pH in the reaction solution, the effects on Sb transformation are described in detail below (see Sect. 3.2).

The H2S concentration fluctuated within the range of 85–175 mg L-1(Fig. 3d). After the addition of Sb(V), the H2S concentration decreased rapidly from 144 mg L-1(day 45) to 107 mg L-1(day 50) and then increased again to 146 mg L-1(day 56). This result likely indicated that the initial addition of Sb(V) inhibited SRB activity,resulting in a reduction in H2S yield. Subsequently, the SRB gradually adapted, and H2S production began to rise.Zhang et al.(2016)also reported that the initial addition of Sb(V) temporarily inhibited the growth of SRB during Sb(V) wastewater treatment. In addition, some heavy metals(e.g.,Cu(II)and Zn(II))can temporarily inhibit SRB activity (Jong and Parry 2003; Kaksonen et al. 2003).

The effects of lactate and ethanol in maintaining SRB growth and producing H2S were essentially the same. For example, when the influent pH was 7, the H2S concentration was 143 ± 17 and 158 ± 14 mg L-1when the carbon source was lactate (days 45–74) and ethanol (days 137–150), respectively. Similarly, Pagnanelli et al. (2012)found that when lactate and ethanol were used as carbon sources, the SRB-induced sulfate reduction efficiencies were similar, and the yields of H2S were also close.

3.2 The transformation and precipitation of Sb

The Sb(V), Sb(III) and Sb(T) concentrations in the Sb(V) wastewater treatment experiment as a function of time are shown in Fig. 3e, f. On the first day (day 45) of Sb(V) treatment, the Sb(V) concentration was only 0.37 mg L-1,indicating that Sb(V)was mostly removed at the very beginning of the treatment.The Sb(V)removal in this period could be predominantly attributed to adsorption on the carrier ceramsite and bacteria because the low Sb(III) concentration between days 45 and 56(0.11–0.12 mg L-1) indicated that the reduction of Sb(V) was weak. Between days 45 and 56, the Sb(V)concentration increased from 0.37 to 3.13 mg L-1, indicating that the Sb(V) adsorption weakened, possibly because the maximum adsorption of Sb(V) could be reached in a short time (Dai et al. 2014; Lee et al. 2018).

Between days 56 and 64,the Sb(V)concentration in the effluent decreased from 3.13 to 1.55 mg L-1, and the Sb(III) concentration increased from 0.11 to 1.11 mg L-1(Fig. 3e). This result indicated that the reduction of Sb(V) occurred and resulted in a decrease in Sb(V). To identify the causes for the reduction of Sb(V), a batch experiment without the addition of sulfate in the medium was carried out for 9 days. When sulfate was absent and H2S was not produced, the Sb(V) in the culture was not consumed, indicating that the Sb(V) was not reduced by SRB enzymatically. Instead, the presence of elemental sulfur (S0) in the precipitates (see Sect. 3.4) indicated the reduction of Sb(V) by H2S.

As mentioned above, the Sb(V) reduction was weak between days 45 and 56 but was significantly enhanced between days 56 and 64. Considering that the H2S concentrations in these two periods (131 ± 18 and 142 ± 11 mg L-1,respectively)were similar while the pH decreased continuously after day 56 (Fig. 3c), the enhanced Sb(V) reduction between days 56 and 64 was possibly caused by the decrease in pH. In a study on the Sb(V) behavior in an anaerobic environment containing H2S, Polack et al. (2009) proposed that a decline in pH promoted the reduction of Sb(V).

Between days 64 and 93, the Sb(T) concentration(2.65–1.44 mg L-1, Fig. 3f) was substantially lower than the initial Sb concentration in the influent (5 mg L-1),indicating that a fraction of the aqueous Sb was removed in this period. The aqueous Sb was proposed to be predominantly removed through precipitation as Sb2S3because the sequential chemical extraction of the precipitates showed that Sb in the precipitate was mainly (>91%) present as sulfides, and the SEM analysis verified the presence of Sb2S3in the precipitates (see Sect. 3.4). The Sb(III) concentration between days 64 and 93 remained relatively stable, likely indicating that Sb(III) was formed by Sb(V) reduction at a rate comparable to that of the consumption of Sb(III) by Sb2S3precipitation. After day 93(pH <7.3) the aqueous Sb(V) was almost completely reduced and hence the decrease in aqueous Sb(III) could only be caused by Sb2S3precipitation. Therefore, the continuous decrease in Sb(III) after day 93 due to the further decline in pH indicated that the decrease in pH also enhanced Sb2S3precipitation. On day 181 (pH 6.5), the Sb(III) concentration decreased to 0.15 mg L-1(Fig. 3e),corresponding to a 96% removal of Sb(T). This concentration is half the pollution emission standard for the antimony industry (0.3 mg L-1) (GB30770-2014).

The above results showed that, after Sb(V) reduction,the product Sb(III) could transform between soluble forms and Sb2S3precipitates in response to a pH change. At a relatively high pH, Sb(III) may be primarily present as Sb(III)-S(-II) complexes (e.g., SbS2-and Sb2S42-) in solutions with a high H2S concentration (Krupp 1988;Filella et al. 2002b; Planer-Friedrich and Wilson 2012;Olsen et al. 2018). Planer-Friedrich and Scheinost (2011)reported that in some hot springs in Yellowstone National Park in the United States,up to 40%of the Sb was present as Sb(III)-S(-II) complexes when the H2S concentration was less than 6 mg L-1. At a relatively low pH, however,these complexes are unstable and dissociate,forming Sb2S3precipitates (Spycher and Reed 1989; Helz et al. 2002).During Sb(V) treatment, aqueous Sb(III) might be mostly present as Sb(III)-S(-II) complexes because the H2S concentration was at a high level of 85–175 mg L-1. These complexes were relatively stable at pH >7.3 (before day 93),dissociated and formed Sb2S3precipitates when the pH decreased to <7.3 (after day 93) and were thoroughly transformed to Sb2S3precipitates when the pH further decreased to 6.5 (day 181). In general, the transformation of Sb was proposed to occur as follows:

The Sb(V) and Sb(III) concentrations between days 56 and 198 were combined into one dataset to simulate the general trend in Sb transformation with declining pH.Because Sb(V)was greatly affected by adsorption between days 45 and 56 (pH >8.1), the data from this period were not included. With declining pH, Sb(V) reduction and Sb2S3precipitation significantly increased,and Sb(III)(i.e.,Sb(III)-S(-II) complexes) initially increased as a result of Sb(V) reduction and then decreased as a result of Sb2S3precipitation(Fig. 4).Similarly,As removal in a biological sulfate-reducing system is also greatly enhanced when pH decreases (Rodriguez-Freire et al. 2014).

3.3 Leaching of Sb in the precipitates

After Sb(V) wastewater treatment, the precipitates in the reactor were leached by an H2S-containing solution to further clarify the transformation between aqueous Sb(III)and Sb2S3precipitates in the H2S system.The variations inpH and the H2S, Sb(V) and Sb(III) concentrations in the effluent are shown in Fig. 5.When the influent was neutral(pH 7) between days 200 and 217, the effluent pH ranged between 6.9 and 7.1,while the Sb leaching was slight,with Sb(V) and Sb(III) concentrations of <0.10 and<0.22 mg L-1,respectively.When the influent was acidic(pH 3) between days 218 and 232, the effluent pH was 5.9–6.3, while Sb was not leached.

Fig. 4 Transformation of Sb with declining pH in Sb(V) wastewater treatment(H2S:85–175 mg L-1;Sb(V)in the influent solution: 5 mg L-1.Note: The Sb2S3 included a small amount of adsorbed Sb.)

Fig. 5 Variations in the parameters of the effluent in precipitate leaching experiments[a pH and H2S concentration;b Sb(V), Sb(III), and Sb(T) concentrations]

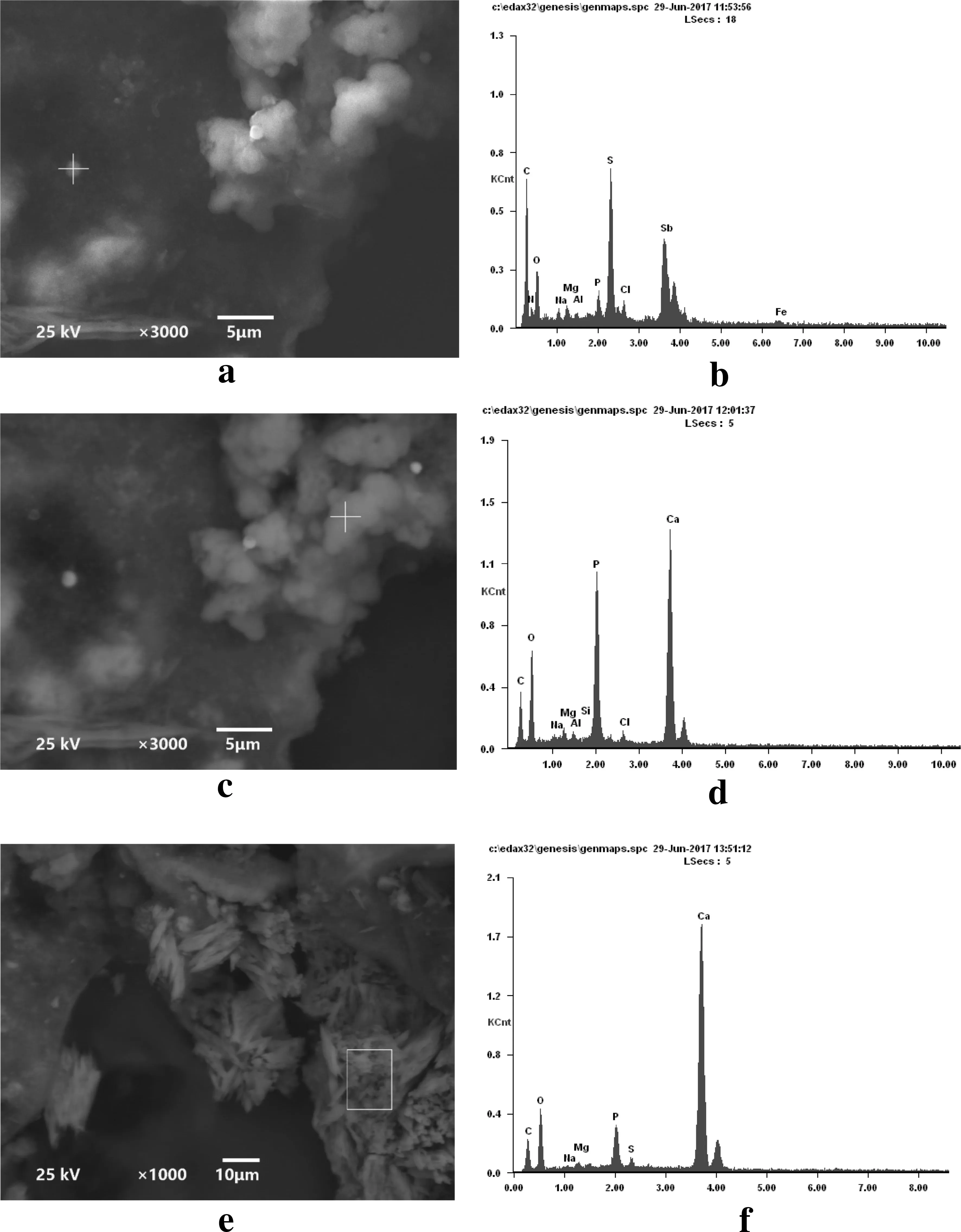

Fig. 6 SEM images and EDS spectra of precipitates (a, b image and composition of dot-like precipitates; c, d image and composition of amorphous precipitates; and e, f image and composition of crystalline precipitates)

When the influent was alkaline between days 233 and 265,however,the effluent pH gradually increased from 6.6 to 7.5, and a large amount of Sb(V) and Sb(III) were leached (Fig. 5b). The Sb(V) concentration in the effluent increased after day 233 and reached 1.35 mg L-1on day 245. Since Sb(V) and Sb(III) were absent in the influent solution, the increase in Sb(V) in the effluent might be caused by the pH-induced desorption of the Sb(V) that accumulated in the solid phases in the reactor due to Sb(V)adsorption at the beginning(especially between days 45 and 56) of the Sb(V) treatment experiment. Previous studies have confirmed that a rise in pH favors the desorption of Sb(V)(Guo et al.2009;Dai et al.2014).This finding indicated that the previously adsorbed Sb(V) had not been reduced despite being exposed to a high level of H2S(>80 mg L-1)for more than 175 days.Similarly,in a study on the removal of As using biochemical reactors,Jackson et al. (2013) found that As(V) in the sand at the bottom of the reactor was not reduced after 104 days of operation. In a previous study on the adsorption of As, it was proposed that As was complexed with active groups carried by bacteria and then adsorbed (Maeda et al. 1985,Taran et al. 2013). Therefore, similar complexation and adsorption of Sb(V) may have occurred and made Sb(V) reduction difficult. After day 245, the Sb(V) concentration in the effluent decreased rapidly, and almost no Sb(V)was detected on day 251,possibly because all of the previously adsorbed Sb(V) had been leached.

The Sb(III) concentration in the effluent increased continuously after the influent pH was adjusted to alkaline after day 233 and reached 2.89 mg L-1on day 265 (Fig. 5b).Because Sb(III)desorption was unlikely to have increased to a very high extent due to the variations in pH (Guo et al.2009), the strong leaching of Sb(III) could be primarily attributed to the dissolution of precipitated Sb2S3instead of the release of previously adsorbed Sb(III). The strong dissolution of Sb2S3after day 233 possibly indicated strong complexation between Sb2S3and aqueous H2S due to the rise in pH.As mentioned above,in the Sb(V)wastewater treatment,the dissolved Sb(III)[mainly occurring as Sb(III)-S(-II) complexes] was almost completely transformed into Sb2S3precipitates when the pH decreased to 6.5(Fig. 3c,e).Therefore,we proposed that an opposite reaction occurred in the leaching experiment after day 233.When the pH of the solution rose to approximately 6.5 (day 234, Fig. 5a), the Sb2S3precipitates likely dissolved due to the formation of Sb(III)-S(-II)complexes with H2S[reverse of reaction(2)].As in minerals also exhibits similar behavior.For example,under alkaline and anaerobic conditions, the presence of sulfide can cause the dissolution of As2S3and the release of As(III) (Floroiu et al. 2004).Moreover,when enargite was leached with sulfide,the As in the mineral could be dissolved by forming complexes with sulfide under alkaline conditions(Balaz et al.2000).Furthermore,under alkaline conditions,the As and Sb in tetrahedrite can be complexed by sulfide and form AsS43-,SbS33-,SbS43-,etc.(Awe et al.2010).

3.4 Characterization of the precipitates

SEM images showed that the treatment of Sb(V) wastewater resulted in amorphous, crystalline, and some dot-like precipitates(Fig. 6).EDS analysis showed that the dot-like precipitates were composed of Sb, S, C, O, Ca, P, Cl, Mg,Fe, and K, with Sb and S as the dominant components(Fig. 6b). The mass compositions (Sb: 14.4%; S: 5.9%)determined by EDS corresponded to a molar ratio of Sb to S of approximately 2:3. This finding indicated that the Sb,when removed from the wastewater,primarily precipitated as Sb2S3. The components coexisting with Sb2S3might originate from the SRB growth medium.The amorphous and crystalline precipitates were predominantly composed of C,O, P, Ca, Mg, Na, etc. (Fig. 6c, e), indicating that these precipitates likely included bacterial cells and minerals.

XRD analysis(Fig. 7)showed the occurrence of stibnite(Sb2S3),S0,calcite(CaCO3),dolomite(CaMg(CO3)2),and quartz (SiO2) in the precipitates. The S0in the precipitate might have been formed in the reduction of Sb(V)by H2S,in which H2S is oxidized to S0. Quartz might originatefrom the water filtration material on the bottom of the reactor. Calcite and dolomite might have been formed by the reaction of Ca and Mg with HCO3-.

The sequential chemical extraction showed that up to 91.3% of the Sb in the precipitates was present as sulfides(Fig. 8). This result confirmed that Sb was primarily precipitated as Sb2S3after its removal from the wastewater.Water-soluble and exchangeable Sb only accounted for 2.2% of the total Sb. These two phases corresponded to adsorbed Sb, indicating that adsorption had only a minor contribution to Sb removal compared with the precipitation of Sb2S3.

4 Conclusions

In the treatment of Sb(V) wastewater by SRB, a sharp change in the pH of the influent solution (3–9) had little effect on the bacteria in a continuous flow reactor, but a small change in the pH of the reaction solution(6.58–7.96)would have significant effects on the Sb transformation.This study demonstrates that the dissociation of Sb(III)-S(-II) complexes would result in the precipitation of Sb as Sb2S3, while the formation of these complexes would not only inhibit the precipitation of Sb but also result in the dissolution of Sb2S3. These processes were highly pH dependent, and the pH value associated with the transformation of Sb species was quantified. Sb(V) was almost completely reduced when the pH decreased to approximately 7.3, and aqueous Sb (mostly Sb(III)-S(-II)complexes)was thoroughly precipitated as Sb2S3when the pH decreased to approximately 6.5. The newly formed Sb2S3was stable at a relatively low pH but began to dissolve through complexation with H2S when the pH rose to approximately 6.5.To increase Sb removal in practice,it is important to control the pH at a relatively low level.

Compared with lactate, the use of ethanol as the carbon source could not only reduce costs but also favor Sb removal because ethanol resulted in a comparable H2S concentration but a lower pH.

Because anaerobic bacteria were used in the treatment,it is necessary to maintain an anaerobic condition and monitor the growth of anaerobic bacteria regularly in practical application.

AcknowledgementsThis study was financially supported by the China National Natural Science Foundation (No. U1612442) and the China National Key Research and Development Program (No.2017YFD0801000).

- Acta Geochimica的其它文章

- Acta Geochimica

- Correction to: A re-assessment of nickel-doping method in iron isotope analysis on rock samples using multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry

- Statistics matters in interpretations of non-traditional stable isotopic data

- Distribution and ecological risks of heavy metals in Lake Hussain Sagar, India

- Discrimination geochemical interaction effects on mineralization at the polymetallic Glojeh deposit, NW Iran by interative backward quadratic modeling

- Ecological risk assessment of surficial sediment by heavy metals from a submerged archaeology harbor,South Mediterranean Sea,Egypt