环境、激进主义与设计:黎巴嫩的新兴实践

卡拉·阿拉莫尼/Carla Aramouny

庞凌波 译/Translatedy by PANG Lingbo

“建筑学与所有设计行业正在发生一场既主动又被动的重大变革:主动寻求发挥更重要的作用,被动响应世界正面临的人道主义与环境危机。”[1]8

2019 年10 月,这是非比寻常的一个月,黎巴嫩爆发大规模示威活动,以反对近几十年来的腐败和公共资金管理不善。迫在眉睫的经济崩盘、大规模具毁灭性的森林大火,以及新一轮征税,是刺激这场大规模抗议的主要原因[2]。在这场民众示威中,艺术家、设计师、建筑师、城市规划师和教育工作者等纷纷呼吁国家进行必要的改革,他们对由于腐败而导致的对自然和建设环境产生直接改变的体制感到愤怒。不过在设计领域里,这样的激进主义并非这场冲突的产物。近些年来,在这样一个经济停滞、社会与环境恶劣到达前所未有的程度的国家,激进主义设计一直位于当地设计学科中心,设计师与建筑师将创造改变的可能性寄托在倡议这样一种必要的机制上。无论是个人层面、实践层面或是学术层面,几项举措在近期已经强有力地将设计师转变为活跃的中间人,将他们所扮演的角色扩展到了直接学科之外,以在更广泛的社会和环境层面发挥干预作用。

全球建筑话语的转变

横览全球,当前建筑修辞和话语的转变,已然清晰地将环境与地球的未来与日益严重的气候危机置于紧迫的辩论议题和设计构想中心。人们对建筑及其对环境影响的关注日益强烈,尤其是对建筑环境对自然资源的巨大影响的关注,早已超越建筑本身的范围,扩大到更大的城市和版图范畴。

从2019 米兰三年展[3]、2020 威尼斯双年展1)到2019 沙迦三年展2)[4],建筑领域究竟对我们的环境,以及对未来几代人的前景带来怎样的影响,这样的问题在这些近期重要的建筑大会与平台上成为了核心关注点。借助2019 年沙迦建筑三年展“未来世代的权利”,阿德里安·拉胡德3)探索了建筑对于人类和自然环境的扩展含义,将未来几代人的权益延伸到更大的自然与环境权利框架上,而不仅拘泥于遮蔽物这一限定。通过三年展,拉胡德动员建筑师、表演者、社会活动家以及其他人参与到对人类和自然环境各种未知的交叉点的思考当中,激发可能的未来。眼下2020 威尼斯建筑双年展即将启动,策展人哈希姆·萨尔基斯4)提出“我们将如何共同生活?”这一问题,将其置于对人类未来重要的重新评估框架之中,置于抛却多年来对地球的忽视与社会的冷漠的集体诉求之中。威尼斯双年展重新将社会公平与环境保护的紧迫性问题视为建筑学领域迫切关切的问题核心,推动建筑师的角色发生有效变化。

几十年来,另一种独特的全球激进主义设计形式则是通过直接的社区参与和设计-建造项目实现的。托马斯·费舍尔在他2008 年出版的《扩展建筑:作为激进主义的设计》一书的前言中对建筑师的角色进行了必要的重新定位,在人道主义危机、气候变化、难民汹涌和全球人口激增的情况下,建筑师应当更多地介入社区[1]9-13。他强调,建筑师必须从为少数人服务向普遍为社区和环境解决所面临的必要和关键问题转变。这一方法早在1999 年就被“为人的建筑”5)[5]采用,近期的代表则是Mass Design Group6),它凭借非盈利实践将建筑置于以人为中心的框架中,以满足灾后和武装冲突地区迫切的社会需求。

除国际论坛和直接的社区参与之外,新兴的调研式设计的研究和倡导透过“法证建筑”7)[6]和“在地研究”8)等的实践,带来了建筑师作为重要调查员的可能性,通过设计与研究探询必要的政治和环境公平。法证建筑利用建筑和可视化作为工具争取社会与环境公平,以探究性研究方法和对环境的取证,揭示数据和调查结果。建筑师作为活动家的这种以实践为基础的角色,进一步地拓宽了建筑和城市运作的框架,使其向空间冲突和司法公正的方向发展。

激进主义与环境的地方形式

在黎巴嫩一个更局部的层面上,设计、建筑以及城市媒介的激进主义一直以来都持续地对更大的社会政治和环境问题产生影响,这是由无能的政权体系和其对环境缺乏可行的可持续愿景所导致的必然。莫娜·哈尔卜[7]指出了在黎巴嫩的近代史上两代主要的城市活动家的崛起,在这段历史中,抹杀了贝鲁特公共空间的战后重建策略,以及在一些大学中新兴的城市项目共同促成了这一趋势。年轻一代利用他们的设计和城市背景来建立联盟、进行非盈利行动,直接带来了近期的变化。

2016 年在贝鲁特,一些独立学者、建筑师、工程师、社会活动家成立了一个名为“我的城市贝鲁特”的联盟[8],参与市政选举。他们提出了一个恢复市政职责、采取全市发展策略的计划,获得了前所未有的支持。他们对贝鲁特的愿景超越了领土政治和党派分歧,而是集中在这一以人民为中心的市政项目上,促成包容、可持续的生活和健康的环境。尽管他们在与老牌政党的竞争中以微弱的劣势落败,但他们所创造的变革的运动和精神直到今天仍能够体现在几位当地的建筑师和城市专家——既有实践者,也有教育家——的工作中。这次竞选所带来的结果是对建筑师/城市规划专家/工程师作为活动家——作为一种有能力对变革产生直接影响且积极参与对建成和自然环境产生影响的决策的专业人士的验证。

1 创造性共享平台Platau,SBAU 2019/Platau, Creative Collectives, SBAU 2019(绘图/Visual: Platau)

Architecture and all the design professions are undergoing a major transformation that is both proactive and reactive: proactive as a search for roles with greater relevance, and reactive as a response to the humanitarian and environmental crises facing the world[1]8.

The month of October 2019 was no ordinary month.Mass demonstrations rose in Lebanon against decades of corruption and mismanagement of public funds.A looming economic crash, large-scale devastating forest fires, and new imposed taxations, were at the heart of the instigation of this massive revolt[2].In this popular uprising, artists, designers, architects,urbanists, and educators, were among the crowd calling for a needed change in the country, exasperated by a system that has directly altered the natural and built environments through corrupt strategies.However,such activism within the design spheres was hardly an outcome of this revolt.In recent years, design activism has been at the heart of the local discipline, where designers and architects have resorted to advocacy as the necessary agency to create change, in a country where the unprecedented level of economic stagnation, social and environmental deterioration, has reached its worst.Several initiatives whether at a personal level, a practice level, or an academic level, have lately grown strongly turning designers into active agents, expanding their roles beyond the bounds of their immediate disciplines to intervene at wider social and environmental levels.

Global Shifts in Architectural Discourse

On a global scale, current shifts in architecture rhetoric and discourse have clearly placed the future of the environment and planet at large with its multiplying climate crisis, at the heart of urgent debates and design speculation.The concern for architecture and its impact on the environment has been increasingly gaining momentum, especially concerning the greater impact of the built environment on our natural resources, going beyond the limits of the building itself to the larger urban and territorial scales.

In recent key architecture conferences and platforms from the 2019 Milano Triennale[3], 2020 Venice Biennale1),and the 2019 Sharjah Triennale2)[4], the question of the architecture field's impact on our environment and the future prospects for coming generations have been proposed as essential concerns.Through the 2019 Sharjah Architecture Triennale "Rights of Future Generations", Adrian Lahoud3)explores the expanded implication of architecture on the human and natural environments, extending the claims of the coming generations beyond the bounds of shelter to the larger frame of natural and environmental rights.Through the Triennale, he engages architects,performers, activists, and others, in reflections on the various uncharted intersections of human and natural environments, provoking possible alternate futures.Today as the Venice 2020 Architecture Biennale is underway, curator Hashim Sarkis4)poses the question of "How Will We Live Together", framing it within a crucial re-evaluation of the future of humanity and the collective desire to retract years of planetary neglect and social indifference.The biennale re-centres the question of social equality and environmental urgency at the heart of the field's urgent calling, pushing the role of the architect towards effective change.

Another distinctive global form of activism in design has been, for several decades, happening through direct community engagement and design-build projects.In his foreword to the 2008 book Expanding Architecture: Design as Activism, Thomas Fisher[1]9-13frames a necessary repositioning of the role of the architect towards more community engagement amidst growing humanitarian crises, climate change, refugee influx,and rising global population.He stresses that architects must shift from serving the minority to engage with necessary and critical problems facing the community and the environment at large.This approach, adopted by practices like Architecture for Humanity5)[5]from as early as 1999, and more recently by Mass Design Group6),places architecture in a human-centred framework through non-profit practices that address urgent social needs in post-disaster and conflict areas.

Further to global forums and direct community engagement, the emergence of investigative design research and advocacy,through practices like Forensic Architecture7)[6]and Situ Research8), has created the possibility of the architect as critical investigator, probing necessary political and environmental justices through design and research.Forensic Architecture uses architecture and visualisation as tools to fight for social and environmental justice, revealing data and findings through their inquisitive research methods and the forensics of context.This type of practice-based role of the architect as activist has expanded further the frame of architectural and urban operations towards spatial conflicts and judicial justice.

Local Forms of Activism and the Environment

On a more local level in Lebanon, activism through design, architecture, and urban mediums,has been consistently growing to impact larger sociopolitical and environmental problematics, necessitated by the inept political system and its lack of a viable sustainable vision for the environment.Mona Harb[7]notes the rise of two main generations of urban activists in the country's recent history, exacerbated by post-war reconstruction strategies that effaced the public domain of Beirut, and fueled by emerging urban programmes in several universities.The younger generation utilised their design and urban backgrounds to establish coalitions and non-profit initiatives that have directly impacted recent change.

In 2016 in Beirut, a group of independent academics, architects, engineers, and activists,formed a coalition[8]running for municipal elections by the name of Beirut Madinati, gathering around them unprecedented support with a programme to rejuvenate municipal duties and adopt city-wide development strategies.Their vision for Beirut transcended territorial politics and sectarian divides to focus instead on a people-centred municipal programme that promotes inclusion, sustainable living, and a healthy environment.Despite their loss by a relatively small margin against established political parties, the movement and spirit for change they created has resounded till today in the work of several local architects and urbanists, both practitioners and educators.What emerged as a result of this campaign is the validation of the role of the architect/urbanist/engineer as activist, as an engaged professional capable of directly impacting change and actively participating in decisions affecting the built and natural environments.

2 黎巴嫩馆,哈拉·尤恩斯/Hala Younes, Lebanese Pavilion(摄影/Photo: @Venice Documentation Project 2018)

3.4 催化行动,包容性公共空间/Catalytic Action, Inclusive public spaces(摄影/Photos: Catalytic Action)

在建筑和城市设计圈内同样也兴起了激进主义运动,他们反对有争议和有破坏性的项目。诸如保护达莉亚沿海地区9)、反对阿什拉菲耶兴建福阿德·布特罗斯高速路10),以及近期拯救比斯里峡谷11)等运动,成功地引发了公众关注,阻止或延迟了项目计划,而且更重要的是,积极地介入了讨论和提议更加可行、合理的选择。随后还举办了几场设计竞赛,邀请当地设计师参与重新设计这些有争议的内容,以实现更具包容性和更可持续的目标。

新兴设计实践

在与全球设计话语转变的对话中,这些不同的举措已然为黎巴嫩的设计激进主义做好了铺垫,使其进一步趋近设计学科与实践的核心地位。这使设计师能够通过一系列新兴的设计倡导模式,诸如推测性提案、直接的社区介入、批判性研究与调查等,积极地参与变革,能够利用他们的工具、技能和权力。他们倡导围绕着自然与建筑环境为中心的多种事业,例如遗产保护、建筑法改革、为城市与清洁环境的权利而斗争。这些努力推动者建筑师与城市学家承担更大的责任,以影响社会与环境变革。

尽管不是直接的激进主义运动,一些建筑师诉诸预测未来的倡议与全球平台的参与,以阐明关键的地方城市或环境问题,提出其他的可能性。由桑德拉·弗雷姆和布洛斯·杜埃希创立的Platau 平台12),通过重新激活现有的开放空间作为新兴区域周边的节点,对贝鲁特新兴的创造性共享平台的潜能进行了仔细考察(图1)。他们的工作在贝鲁特参加2019 首尔建筑与城市双年展(SBAU)的城市展览板块时的研究与视觉化过程中得到了发展。他们的方案强调城市策略与建筑干预,通过激活可用的开放空间来加强这种集体平台的发展。

另一全球论坛上,哈拉·尤恩斯批判性地展现了黎巴嫩自然地形的遗存,将其作为一种必要的、有价值的、对建筑环境的战略性重新设计有需求的资源[9]14-15。这一策展作品在2018 威尼斯国际建筑双年展期间为黎巴嫩馆所设计,它强调了剩余土地的脆弱和可能资源的稀缺,意图识别潜在空间,以重新思考土地的未来。这个艺术装置(图2)包含了贝鲁特河盆地的中心物理模型,以及展示其随时间形态变迁的投影视觉效果。这个广为流传的作品在双年展这一全球平台上使当地土地流失的危机得到了集中讨论。

更直接的倡导模式包括设计师采用非盈利组织的框架,直接参与社区,并为重要的社会问题开发具有影响力的项目。Warchee 工作营这一由建筑师阿纳斯塔西娅·鲁斯与米歇尔·拉鲁-查理成立的非盈利组织,其使命即通过培训不同建筑技能和专业方向的女性,加强建筑行业的性别平等13)。作为鲁斯建筑实践的平行实体,Warchee 致力于为黎巴嫩的女性赋能,通过实地训练基地和可变制造中心,使她们成为建筑行业的有效参与者。

“催化行动”,由乔安娜·达巴杰和里卡多·卢卡·孔蒂成立的往返于伦敦和贝鲁特两地的非盈利组织,聚焦在高危和高需求地区提高生活环境品质。他们介入黎巴嫩境内外一些难民营,为它们设计和建造教育与游乐设施。他们在黎巴嫩不同地区的游乐园项目(图3、4)为贫困社区的孩子们提供重要的社交和娱乐空间。通过他们的努力,催化行动将设计作为一种赋权和参与的工具,超越了他们作为建筑师的角色,走向直接的行动主义,带有必要的社会影响力。

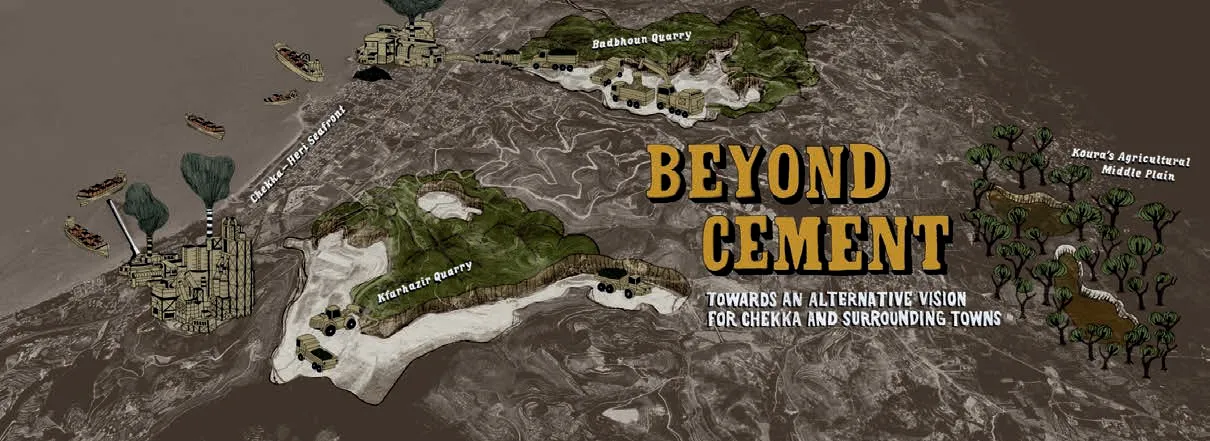

依托于调查研究与视觉化,“公共工程”14)着手于国内紧迫的城市与环境领域,将其作为直接行动的模式,试图揭示未知和关键的事实来引发关注、传播知识。他们对切卡高原和水泥厂的调查,对祖克·莫斯比发电厂对社区健康影响的调查,以及对近期住宅空间不平等的调查,引发了人们对这些问题的广泛关注。他们的工作还引入了设计竞赛(图5),让更广泛的建筑与城市社区向有弹性的、灵敏的方向发展,例如他们的“Think Housing”竞赛,推动了黎巴嫩经济适用房这一重要战略的出现。

5 Public Works的Beyond Cement竞赛/Public Works, Beyond Cement competition(摄影/Photo: Public Works)

Activist campaigns have also emerged from within the architecture and urban circles, rising against controversial and devastating projects.Campaigns such as the protection of the coastal area of Dalieh9),the campaign against the Fouad Boutros highway in Achrafieh10)and more recently the Save the Bisri Valley11), among many others, succeeded in raising public awareness, halting or delaying the planned projects, and more importantly, actively engaging in debates and proposals for more viable and equitable alternatives.Several design competitions were also subsequently launched inviting local designers to take part in reimagining these controversial contexts towards more inclusive and sustainable goals.

Emerging Design Practices

In dialogue with the global shifts in design discourse, these different initiatives have been paving the way for design activism in Lebanon to become further situated in core design disciplines and practice-based endeavors.They are allowing designers to actively engage in change and to utilise their tools, skills, and powers through a range of emerging design advocacy modes, from speculative proposals, direct community interventions, to critical research and investigation.They advocate different causes centred around the natural and built environments, such as heritage preservation,reforming the building law, fighting for rights to the city and to a clean environment.These endeavors are pushing architects and urbanists to take up more substantial responsibilities to impact social and environmental change through their agency.

Although not direct acts of activism, some architects have resorted to speculative advocacy and engagement in global platforms to shed light on key local urban or environmental issues and to propose alternate possibilities.Platau12), founded by Sandra Frem and Boulos Douaihy, reflected on the potential of creative collective hubs to emerge in Beirut, through re-activating available open spaces as nodes around currently emerging areas(Fig.1).Their work was developed through research and visualisation for the Beirut participation in the 2019 Seoul Biennale for Architecture and Urbanism (SBAU) within its Cities Exhibition component.Their proposal emphasised on urban strategies and architectural interventions that can be adopted to augment the development of such collective hubs by activating available public lots.

In another global forum, Hala Younes[9]14-15critically exposed the remains of the Lebanese natural terrain, framing it as a necessarily valuable resource requiring a strategic reimagining of the built environment.The curatorial work was developed for the Lebanese Pavilion during the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale and highlighted the fragility of the remaining territory and the scarcity of possible resources, attempting to identify potential spaces to rethink the future of the terrain.The installation(Fig.2) included a central physical model of the Beirut river basin, with projected visuals displaying its morphosis through time.The highly published work centred the debate on the criticality of the local terrain from the Biennale's global platform.

A more direct mode of advocacy includes designers adopting the framework of non-profit organisations to directly engage with the community and develop impactful projects for crucial social causes.The mission of Warchee13), a non-profit founded by architect Anastasia el Rouss with Michelle Larue-Charlue, is to enforce gender equity in the construction field, by training women in different construction skill sets and trades.As a parallel entity to El Rouss's architecture practice, Warchee works on enabling Lebanese women to be effective participants in the construction industry through on site-training stations and mobile fabrication hubs.

Catalytic Action, a non-profit founded by Joana Dabaj and Riccardo Luca Conti between London and Beirut, focuses on impacting the quality of the living environment in areas of high risk and need.Their interventions have been developed for several refugee camps in Lebanon and beyond, through designing and building educational and playground facilities.Their playground projects (Fig.3,4) in different areas in Lebanon provide children in underprivileged communities with vital social and recreational spaces.Through their work, Catalytic Action uses design as an empowering and participatory tool, transcending their role as architects towards direct activism and necessary social impact.

Embedded in investigative research and visualisation as modes of direct activism, Public Works14)tackles urgent urban and environmental areas in the country, shedding light on uncharted and critical realities to raise awareness and disseminate infor med knowledge.T heir investigations of the Chekka plateau and cement plants, the Zouk Mosbeh powerplant's impact on the community's health, and more recently spatial inequalities in residential spaces, have initiated key awareness on these issues.Their work also introduced design competitions (Fig.5) to engage the larger architecture and urban community towards the development of resilient and sensitive proposals, such as their 'Think Housing' competition that pushed for critical strategies to affordable housing in Lebanon.

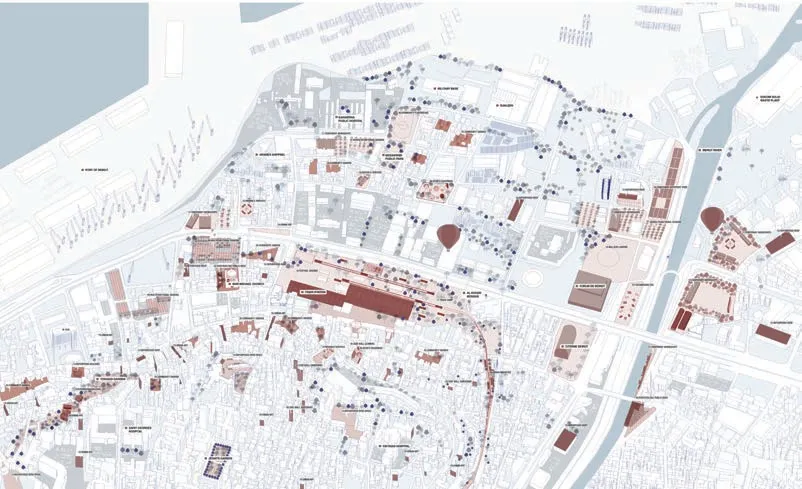

Equally, the work of Antoine Atallah, architect and urbanist, utilises research and mapping as means to highlight profound changes affecting urban spaces in Beirut and the larger Lebanese territory.His critical analysis of Beirut's spatial transformation from the early 20th century till today, through aerials, cadastral maps, and panoramic imagery,has created a powerful visual interpretation of the radical changes that have drastically reshaped the urban fabric (Fig.6).Atallah has also played a crucial role as member in the Save Beirut Heritage NGO and the campaign to stop the aforementioned Fouad Boutros Highway, through his research and mappings of the neighbourhood's characteristics,the highway's expected devastating impact on local heritage, and of possible alternatives.

Practice-Based Engagement: The Case of AUB

Intersecting design research and activism have embedded into academic institutions, and prominently so at the American University of Beirut(AUB).Initiatives such as BePublic and Di-Lab at the Department of Architecture and Design15)have transposed into academic circles different approaches to community-based and public interest design.Physical interventions, sometimes in the form of reflective installations and more often as operative built structures, allow faculty and students to engage actively in their local context and in areas of critical need.

BePublic, initiated by Rana Haddad, uses the design studio as a platform to intervene with students on various urban conditions and reflect on public space and civic rights in Beirut.Through temporary design installations, BePublic's work provokes the city dweller to engage with the designer and to look beyond the obvious, raising awareness on socio-political issues impacting their environment.In "Radio Silence" (Fig.7,8) the project inserts a see-saw installation on a previously closed-off public park's gate, challenging the imposed division between two user communities.

Founded by Karim Najjar, Di-Lab works on turning public interest design into an action-based process, working with students, municipalities,and the community at large to identify and build needed sustainable structures.The focus is towards emergency and post- disaster interventions that use a participatory design-build process and integrate sustainable materials and local know-how.The Bar Elias playground and canopy (Fig.9,10) shown here,help provide a needed space and shaded area in a school for Syrian refugees in the Bekaa valley, while integrating local recycled materials.

7.8Radio Silence 的BePublic作品,2016/BePublic, Radio Silence, 2016(供图/Courtesy of BePublic lab, 摄影/Photos:Mario Khoury)

同样,建筑师与城市学家安托万·阿塔拉的作品,利用研究和制图手段,突出了对贝鲁特甚至更大范围的黎巴嫩领土内影响城市空间的深刻变化。他通过鸟瞰图、地籍图和全景图,对贝鲁特自20世纪早期至今的空间转型进行了批判性分析,对彻底重塑城市结构的根本性变化进行了强有力的视觉阐释(图6)。阿塔拉作为成员还在“保护贝鲁特遗产”这一非政府组织中起到了重要作用。他参与了上文曾提及的福阿德·布特罗斯高速公路停工运动,研究并针对周边地区性质、高速公路预计将会给当地的遗产带来的毁灭性影响以及可能的其他选择进行了制图。

基于实践的参与:贝鲁特美国大学案例

交叉学科的设计研究与激进主义也已深入学术机构,在贝鲁特美国大学尤为突出。诸如建筑设计系的BePublic 和Di-Lab 等项目已进入学术领域15),通过不同方法进行基于社区和公共权益的设计。物理介入——有时是反思性装置设计的形式,更经常的则是可操控的建构的形式——使得教师与学生能够积极地参与到他们所处的环境中和那些有紧迫需求的区域里。

BePublic 由拉娜·哈达德发起,借助设计工作室为平台与学生就贝鲁特的多种城市现状进行交流,并反思公共空间和公民权利。通过一些临时性的装置设计,BePublic 的作品激发城市居民加入设计师行列,突破表面现象,引发人们对影响他们环境的社会政治问题的关注。在“无线电静默”(图7、8)项目中,它在关闭的公园大门上插入了一个跷跷板装置,挑战了两个社区之间强加的分隔。

Di-Lab 由卡里姆·纳杰尔创立,致力于将公共利益设计变为一种以行动为基础的过程,在此过程中,学生、市政当局以及整个社区共同合作,识别并建设必须的、可持续的构筑物。Di-Lab 关注紧急事件与灾难之后的介入,采用参与式设计-建造过程,并整合可持续材料与地方工艺。这里展示的是巴尔·伊利亚斯风雨操场(图9、10),为位于贝卡谷的一所叙利亚难民学校提供了必需的空间和荫蔽的场地,并利用了当地的回收材料。

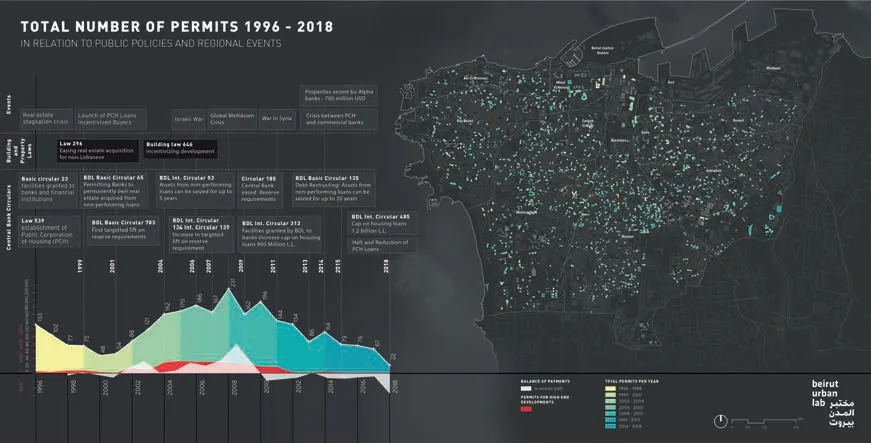

此外,由莫娜·法瓦兹、莫娜·哈伯、豪伊达·哈尔西与阿哈默德·加比几位教授共同创立的贝鲁特城市实验室,一个新成立的研究中心,利用城市调查、策略设计、政策倡议为更大范围的研究和实践领域提供信息。该实验室的目标始于城市活动家、设计师、变革者们的生态系统建立联系,提供重要的城市信息的开放资源,来更广泛地影响当地的这些领域。他们的合作拓宽到了多种专题,从城市政治、城市治理、强制搬迁到公共领域私有化,强化了对地图和视觉化作为知识生产的实验与分析工具的使用(图11)。

结语

通过以上这些倡议行动、宣传平台和设计方法,黎巴嫩的建筑和城市领域已经转向了积极的努力,创造了有意义和有成效的行动,以改善建筑和自然环境恶化的现实。设计师们已经承担起责任,来唤起人们的关注,并为那些正在威胁城市、村镇以及更大范围的政策提供重要的替代方案。在一个人类不断面临着人道主义和环境危机的世界,黎巴嫩的情形映射出的是正处于变革的全球话语,越来越多的建筑师和设计师正在从服务少数特权阶层,转向去影响可能的全球转型。□

9.10 巴尔·伊利亚斯风雨操场, Di-Lab/Bar Elias Playground,Di-Lab(摄影/Photos: Di-Lab / Karim Najjar)

11 建造许可分布图,Beirut Urban Lab / Mapping building permits, Beirut Urban Lab(绘图/Visual: Beirut Urban Lab)

Furthermore, the Beirut Urban Lab, a newly established research hub, co-founded by professors Mona Fawaz, Mona Harb, Howayda al Harithy and Ahmad Gharbieh, uses urban investigations,strategic design proposals, and policy advocacy,to inform the larger research and practice fields.The aim of the lab is to engage with the ecosystem of urban activists, designers, and change makers,and to provide open-source critical urban knowledge that can widely impact the local fields.Their collaborative work expands across multiple thematics ranging from urban politics, governance,forced displacement, and privatisation of public domain, and reinforces the use of mapping and visualisation as experimental and analytical tools for knowledge production (Fig.11).

Conclusion

As seen from these initiatives, advocacy platforms, and design approaches, both the architecture and urban fields in Lebanon have turned towards activist endeavors to create meaningful and effective actions to help improve the deteriorated realities of the built and natural environments.Designers have taken it upon themselves to raise awareness and provide critical alternatives to strategies that are endangering cities, towns, and the larger territory.In a world continuously confronting humanitarian and environmental crises, the local scene reflects a changing global discourse, where an increasing number of architects and designers are shifting away from serving the privileged few to affect a possible planetary transformation.□

注释/Notes

1)详见/2020 Venice Architecture Biennale: How Will We Live Together?, curated by Hashim Sarkis, https://www.labiennale.org/en/news/biennale-architettura-2020-how-will-we-live-together

2) 详见/2019 Sharjah Architecture Triennale, Rights of Future Generations, curated by Adrian Lahoud,https://rfgen.net/en/page/theme.

3)生于黎巴嫩的建筑师和研究员阿德里安·拉胡德,目前担任英国皇家艺术学院建筑学院的院长。/Adrian Lahoud, architect and researcher of Lebanese origin,currently serving as Dean of the School of Architecture at the Royal College of Art, UK.

4)哈希姆·萨尔基斯,黎巴嫩建筑师和教育家,目前担任麻省理工学院建筑与规划学院的院长。/Hashim Sarkis, Lebanese architect and educator,currently serving as Dean of the School of Architecture and Planning at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

5)最具影响力的非盈利建筑实践之一,成立于1999年,创始人卡梅隆·辛克莱和凯特·斯托尔。他们的工作方式和作品当时在Design Like You Give a Damn 发表,详见参考文献[5]。/One of the more influential non-profit architecture practices, founded in 1999 by Cameron Sinclair and Kate Stohr.Their approach and work were later published in Design Like You Give a Damn, see Reference [5].

6)由迈克尔·墨菲创立于美国波士顿,MASS Design Group 致力于帮助促进平等和社会公正的人道主义建筑项目。/Founded by Michael Murphy in Boston, USA,MASS Design Group works on humanitarian projects helping to promote equality and social justice through architecture.https://massdesigngroup.org/about

7)Forensic Architecture 是一个设立在伦敦大学的研究机构,由埃亚·魏兹曼创立。其作品关注“侵犯人权案件的进阶空间和媒体调查,涉及并代表受到政治暴力、人权组织、国际起诉主体、环境公正团体及媒体组织影响的社区群体” /Forensic Architecture is a research agency based in the University of London and founded by Eyal Weizman.The work focuses on "advanced spatial and media investigations into cases of human rights violations,with and on behalf of communities affected by political violence, human rights organisations, international prosecutors, environmental justice groups, and media organisations." https://forensic-architecture.org/

8) Situ Research 是设立于纽约的实践机构,与Situ Studio 为平行机构,是一家“致力于建筑、城市、政治和人权的交叉领域的跨领域应用研究分支机构”。/Situ Research, New York based practice, and a parallel entity to Situ Studio, is an "interdisciplinary applied-research division working at the intersection of architecture, urbanism, policy and human rights."https://situ.nyc/research

9) 保护达利亚的公民运动,导致一个私人高端开发项目的终止以及后续达利亚自然地被列入世界历史遗迹观察名单。/The Civil Campaign to Protect Dalieh, led to the halting of a private highend development project and the subsequent listing of the Dalieh natural site in Beirut under the World Monument Watch list https://dalieh.org/&https://www.wmf.org/project/dalieh-raouche

10)反对福阿德·布特罗斯高速路运动和替换提案/Stop Fouad Boutros Highway campaign and proposed alternatives, https://stopthehighway.wordpress.com/

11)拯救比斯里峡谷运动/Save the Bisri Valley campaign alternatives, https://en.annahar.com/article/1098856-bisri-dam-an-ongoing-controversy

12)详见/Platau: Platform for Architecture and Urbanism, http://www.platau.info/

13)详见/Warchee, NGO, http://www.warchee.org/

14)Public Works ,一个多学科设计及研究工作室,由阿比尔·萨克苏克和纳丁·别克达切创立/Public Works, a multidisciplinary design and research studio, founded by Abir Saksouk and Nadine Bekdache,https://publicworksstudio.com/en/about

15)关于贝鲁特美国大学建筑与设计学系的倡议详情详见/Further information on initiatives by the Department of Architecture and Design at AUB: Di-Lab, BePublic, and the Beirut Urban Lab https://www.aub.edu.lb/msfea/ard/Pages/default.aspx

参考文献/References

[1] FISHER T.Public Interest Architecture: A Needed and Inevitable Change [M]// BELL B, WAKEFORD K.(ed.) Expanding Architecture: Design as Activism.Bellerophon Publications, 2008: 8-13.

[2] SULLIVAN H.The Making of Lebanon's October Revolution [J/OL].The New Yorker, October 29, 2019.https://www.newyorker.com/news/dispatch/themaking-of-lebanons-october-revolution.

[3] ANTONELLI P, TANNIR A.Broken Nature :Triennale Di Milano [M].Verona: Elcograf, 2019.

[4] LAHOUD A, BAGNATO A.Rights of Future Generations: Conditions[M].Hatje Cantz, Arab Institute for Research and Publishing, 2019.

[5] SINCLAIR C, STOHR K.Design Like You Give a Damn: Architectural Responses to Humanitarian Crises[M].London: Thames and Hudson, 2006.

[6] WEIZMAN E.Forensic Architecture, Violence at theThreshold of Detectability[M].New York: Zone Books, 2018.

[7] HARB M.Cities and Political Change: How Young Activists in Beirut Bred an Urban Social Movement[D].Power to Youth, Paper No.20, September 2016, ISSN 2283-5792.

[8] FAWAZ M.Beirut Madinati and the Prospects of Urban Citizenship [EB/OL].The Centur y Foundation online, April 16, 2019.https://tcf.org/content/report/beirut-madinati-prospects-urbancitizenship/?session=1

[9] YOUNES H.The Exhibition[M]// The Place That Remains: Recounting the Unbuilt Territory, YOUNES H (ed.).Skira, 2018: 14-15.

[10] BELL B.Expanding Design Towards Greater Relevance [M]// BELL B, WAKEFORD K.(ed.)Expanding Architecture: Design as Activism.Bellerophon Publications, 2008: 14-17.