重思当代中东的城市景观

穆罕默德·加里普尔/Mohammad Gharipour

黄华青 译/Translated by HUANG Huaqing

中东的城市景观:文化与政治背景

中东地区的地理范畴东至阿富汗,西至埃及,北至土耳其,南至也门与阿曼。这个区域因其传承两千多年的古代园林而闻名。尽管对于伊斯兰世界的园林传统的研究颇多——从北非、西班牙直到印度次大陆,但针对现代城市景观的研究仍应加强,以揭示其对当代中东历史的革命性影响1)。

在20 世纪的中东城市存在一系列因素,推动了城市空间的公共休闲功能的拓展,包括:经济现代化、工业化程度日益深化、农村进城移民的不断增长、城市扩张对农村地区的侵蚀及其破坏性的环境影响、低成本住宅项目的建设。现代主义作为一场持续进行的运动,通过一系列城市公园和景观项目设计,在现代的中东首都城市建立了充满活力的社会关系和文化自觉。重建或新建的景观项目象征着声望——在石油繁荣期尤为如此[1]69。例如,经济发展促使沙特阿拉伯政府在利雅得施行了一系列举足轻重的规划项目。这些项目的规划者试图通过1990 年代城市公园的创建,塑造文化身份、公共空间和国家庆典的概念。这些公园在根本上取代了景观化的棕榈园——那些棕榈园曾在1970 年代的城市快速扩张中遭到侵占,让位于为不断增长的城市人口提供的住宅和公共设施。

20 世纪末,公共空间被称颂为中东社会的民主、进步与开放性的象征。尽管不断扩张的城市景观标志着现代和发展,但其中的公共功能似乎也与某些政府的极权主义主张相悖——即使这些政府领导者依然对公共空间大加赞美,认为它是民众发声及国家民主的象征。所谓“民主空间”的概念,就是要让能够享受某一特定空间或场所的人数最大化——这一场所可以是经过设计的,也可以是天然存在的。公共空间被普遍作为社会及政治表征的场景,作为政治自主性及民主化的所在[2]10。在世俗化的年代,公共广场及城市公园成为独立抗议的主要舞台——后来又成为它的纪念场。城市公共空间为社会互动、社区聚集、集会或政治行动创造了契机[2]15。这一关键功能也解释了,为何如爱德华·苏贾[3]13-30等城市地理学家将公共空间视为建筑师为空间正义作贡献的机会——只需让普罗大众认识到公共空间的重要性[2]27。

尽管城市花园的概念似乎很吸引政客——至少在一开始是如此——但它在现实中的公共使用状况却时常成为政客们焦虑的来源……甚至更差。“阿拉伯之春”期间在突尼斯和埃及发生的占领公园和广场的运动,便凸显了城市景观在这方面的潜在贡献——为反对统治王朝、政府或独裁者的政治集会、游行和抗议提供了便利。反过来,政府支持者同样会利用这些公共空间作为阵地,以支持战争、冲突和政治霸权。2014 年在伊斯坦布尔格兹公园发生的抗议,最初只是民众反对一项企图拆除这一城市公园的规划,后来便升级扩散为一场全国性的针对政府的抗议(图1)。这些例子都凸显了公共空间在当代中东社会的激进运动中扮演的作用。

1 格兹公园抗议,塔克西姆广场,伊斯坦布尔,土耳其/Gezi Park Protests, Taksim Square, İstanbul, Turkey (图片提供/Courtesy of Alan Hilditch, 2013)

2 谷歌地球中的多哈沿海道路/Google Earth view of Doha Corniche(图片提供/Courtesy of Anna Grichtig, 2015)

3 扎因代河河滨公园,伊斯法罕,伊朗/The urban park along the Zayanderud (river), Isfahan, Iran(图片提供/Courtesy of Sahar Hosseini, 2018)

Urban Landscapes of the Middle East: Cultural and Political Context

As a region, the Middle East stretches eastto-west from Afghanistan to Egypt, and north-tosouth from Turkey to Yemen and Oman.The region is recognised for its historic gardens that have been shaped for over two millennia.While there are numerous studies of garden traditions in the Islamic world from North Africa and Spain to the Indian subcontinent, modern urban landscapes deserve to be studied further to clarify their revolutionary impact on the contemporary history of the Middle East1).

A number of stimuli spurred the expanded use of urban spaces for public recreation in the cities of the Middle East in the 20th Century:the implementation of economic modernisation,increased industrialisation, the growing migration of people from rural to urban areas, the encroachment of urban growth into rural areas and its damaging environmental consequences, and the construction of low-income housing projects.Modernism as an ongoing process has established vibrant social relations and cultural identities for modern capital cities through the design of urban parks and landscapes.Redesigned or new landscapes signified prestige, especially in the midst of the oil boom.[1]69For instance, economic development encouraged the government of Saudi Arabia to implement major planning projects in Riyadh.These planners attempted to formulate concepts of cultural identity,public space, and national ceremony through the creation of urban parks in the 1990s.These parks in essence replaced landscaped palm gardens that were eliminated through the rapid expansion of the city in the 1970s when planners struggled to provide residences and public buildings to accommodate the growing urban population.

In the late-20th century public spaces were celebrated as symbols of democracy, progress, and openness in Middle Eastern societies.Despite the spread of urban landscapes as signifiers of modernity and development, their public use seems to be contrary to the totalitarian mission of some governments - even though their leaders extol public space as a symbol of public voice and democracy.The idea of a democratic space seeks to maximise the number of people who can enjoy a certain space or place, whether it is designed or organic.Public space is universally utilised as the setting of social and political representation, as the locus of political mobilisation and of democratisation[2]10.In an age of secularisation, public squares and urban parks have become important arenas for staging independence protests - and later for commemorating them.Urban public spaces create opportunities for social interactions, community gatherings, meetings, or political actions[2]15.This essential function explains why urban geographers such as Ed.Soja[3]13-30consider public space as an opportunity for architects to contribute to spatial justice, simply by making the larger public aware of its significance[2]27.

Although the concept of the urban garden seems to attract politicians - at least initially - its actual public use often becomes a source of angst...or worse.The occupation of parks and squares in Tunis and Egypt during the "Arab Spring" highlights the potential contribution of urban landscapes to facilitate gatherings, political demonstrations, and protests against ruling monarchies, governments, or dictatorships.Conversely, government supporters have also utilised these public spaces as sites to advocate for war, conflict, and political supremacy.The 2014 protests in Gezi Park in Istanbul, which began as a popular response to plans calling for the destruction of this urban park, generalised and spread as national protests against the ruling government (Fig.1).These instances highlight the role of public spaces in social activism in contemporary societies in the Middle East.

Urban landscapes in the Middle East are expressed in different forms and with various functions.The most obvious form is the urban park, which has received so much attention from municipalities and local governments.Urban parks,which have been used as recreational areas for the public and as tools to combat air pollution, have also served as important tourist destinations.Two notable examples of these successful urban parks can be found in the seaside parks in Doha (Fig.2)and the urban parks along the Zayanderud River in Isfahan (Fig.3), which have functioned as lively zones of urban culture.Other types of landscapes that have been increasingly incorporated in urban settings over the last two decades include zoos, bird parks, beach landscapes, flower parks,sculpture parks, water parks, memorial parks, and even cemeteries.Many of these sites have served as recreational locales for urban residents.Their proximity to urban monuments or public sites contributes to their functionality in the urban context, whether they are used as social space for the elderly or for skateboarding for a city's youth.Despite being "public", some of these landscape projects across the Middle East have remained open only to selected groups of people2).

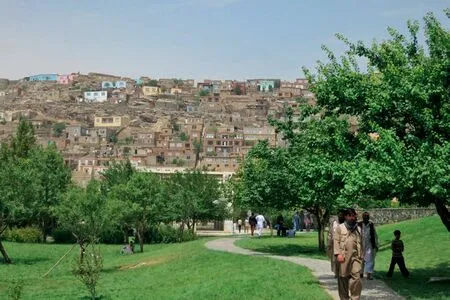

The financial and professional support received from international organisations such as UNESCO,the World Monuments Fund, and the Aga Khan Foundation have contributed to the construction of new landscapes and the preservation of older forms.The Al-Azhar Park in Cairo is an example of a successful international initiative that received popular interest and support.Similarly, the Gardens of Babur in Kabul, which was fully rehabilitated between 2002 and 2004 with the support of the Aga Khan Historic Cities Programme, represents an urban project aimed at reviving a cultural identity amidst the development of post-war Kabul (Fig.4)[4]25.The success of these two projects extends beyond their impact on the lives of the residents as recreational sites; they have also provided employment opportunities for local workers,craftsmen, and architects.

中东城市景观可表现为不同的形式及多样的功能。最常见的一种便是城市公园,它已受到国家及地方政府的密切关注。城市公园不仅是公众的休闲场所、抗击空气污染的有效工具,也是重要的旅游目的地。这里列举两个成功的城市公园案例:多哈的海滨公园(图2)和伊斯法罕的扎因代河河滨公园(图3)。它们都成为城市文化的活跃区域。其他在过去20 年间持续纳入城市环境的景观类型还包括:动物园、鸟类公园、沙滩、花卉园、雕塑园、水景园、纪念公园,甚至包括墓地。其中大部分场所都是城市居民的休闲场所。这些景观往往接近城市中的标志性建筑或公共场所,这使得它们更容易在城市中发挥功用——无论是作为老年人的社交空间,还是年轻人的滑板场地。尽管是“公共的”,但在中东各地,这类景观项目还是存在一部分是仅向特定群体开放的2)。

从联合国教科文组织、世界遗产基金会、阿卡汉基金会等国际组织获得的资金和技术支持,帮助当地建造了很多新的景观,并对历史景观进行了保护。开罗的阿兹哈尔公园就是这样一个由国际力量发起的成功项目,获得了公众的关注和支持。类似的项目还有喀布尔的巴布尔花园,它在2002-2004年间受阿卡汗历史城市计划资助而得到彻底修复,它代表了一类在战后喀布尔发展中试图复兴文化认同的城市项目(图4)[4]25。这两个项目的成功,不仅在于它们对当地居民休闲生活的影响,它们还为当地工人、工匠和建筑师提供了职业机会。

当代考量:环境与文化

不断恶化的环境问题正在威胁城市所在的区域——无论是由于缺乏政策规划,或是优质规划未能得到成功执行,都意味着城市需要更多生态友好的项目。空气污染、持续的沙漠化、土地退化和干旱问题,都要求政府提出更加大胆有效的环境政策,包括在城市内外扩建公园和森林3)。对于可持续性建筑及城市规划的需求,促使政策制定者更多地在发展规划中不断提升自然资源的重要性。反过来看,从城市中心到非正规建设的城市边缘地区,都在发生地方性城市设计的显著转型,这促使景观被用作一种策略,以强调生态重于形态、网络化表面重于城市建成形式的理念,同时景观还可作为在边缘地区创造社会文化网络的工具[5]8。

社会公正、节能和环境保护等议题促生了一批规划、景观和建筑项目。其中一个重要案例是阿联酋阿布扎比的马斯达尔——这座新城完全按照环境可持续性原则进行规划设计(图5)[6]23-37。这类当代项目一方面需要抗击干旱、浪费、污染甚至是温室效应,另一方面还要促进净水和能源的公平分配,并在具有长期阶级隔离传统的中东社会推动社会公正的理念。随着城市与景观间的界限逐步消退,环境敏感度正不断上升——这推动了一系列新政策的产生,皆基于对可持续性、洁净空气和用水、高效公共交通体系的考量[7]10。

4 巴布尔花园,喀布尔, 阿富汗/The Bagh-i Babur, Kabul,Afghanistan (图片提供/Courtesy of Wikimedia)

5 马斯达尔市区/Masdar City(图片提供/Courtesy of Foster +Partners)

Contemporary Concerns: Environment and Culture

Increasing environmental problems threatening urban areas - whether they are based on lack of policy planning or on the unsuccessful implementation of well-intentioned schemes - indicate a need for more ecologically-efficient projects.Air pollution, growing desertification, land degradation, and drought have also necessitated establishing more aggressive environmental policies by governments, including the expansion of parks and forests both inside and outside cities3).The need for sustainable architecture and urbanism has motivated decision-makers to consider natural resources in their development plans on an increasing basis.Conversely, the major shift in regional urban design from city centres to their marginal areas with informal development has resulted in using landscape as a means to stress the importance of ecology over morphology, network surface over urban form, and as a tool to create sociocultural networks in marginal spaces[5]8.

Social equity, energy conservation, and environmental concerns have driven a number of planning, landscape, and architecture projects.One important example is the planned city of Masdar in Abu Dhabi in the UAE, which was purposefully designed to promote environmental sustainability(Fig.5)4)[6]23-37. While contemporary projects should combat drought, waste, pollution, and even the greenhouse effect, they should facilitate the equitable distribution of clean water and energy, as well as actively promote social equity in the traditionally class-segregated societies of the Middle East.As the barriers between cities and landscapes fade, environmental sensitivity is growing - resulting in policies based on concerns for sustainability, cleaner air and water, and efficient public transportation systems[7]10.

Another crucial factor to consider in the design of the contemporary landscapes is local history and tradition.Local professionals and academics are now reexamining ideas coming from the West,which were formerly praised and copied, through a much more critical lens.The growing interest in the region's diverse cultural heritage, especially among ordinary people and NGOs, has increased public awareness of the environmental and cultural benefits of urban projects.The urban landscapes of the Middle East have been transformed from passive settings for recreation to dynamic theatres for civic engagement.Resonating with the real rhythms of daily life, these new spaces are used as a medium to connect and support a great variety of places,people, and activities across multiple scales or levels of influence[8]32.They can potentially integrate isolated zones or enclaves within the city through a wide range of connections and transportation infrastructures working across various scales[8]45.

The increasing density within large cities also calls for the repurposing of discarded or outdated infrastructures or abandoned sites, such as former military installations[7]6.The Al-Azhar Park, built on a wasteland, is a very successful example of this trend currently making a difference in the lives of Cairo residents (Fig.6).This park, located in close proximity to a historic district, brought life back to low-income neighbourhoods while also supporting tourism and the local economy.While some tourismoriented projects promote an orientalist nostalgia that depicts the old neighbourhoods as fossilised and immortal artifacts, others acknowledge evolving aspects of the city, culture, and residents.For instance, in Al-Salt's historic urban landscape in Jordan, developers paid particular attention to its long-term potential as a new tourist destination,and purposefully marketed the area's tourism infrastructure and services (Fig.7).In this case,urban rehabilitation policies were designed to promote tourism and the historic urban fabric simultaneously.Indeed, tourism has been the source of spontaneous social activities that were not necessarily inherent to the nature of this area's urban structure and its fragmentary growth[9]317.

Either designed as public plazas or parks in urban or marginal areas, contemporary landscape projects have played a vital role in ushering a new era into modern Middle Eastern cities - and in particular in shaping social culture in such a way that the public has a voice.With roots in early modern urban gardens of this region, the phenomenon of the urban landscape has improved the quality of life in cities in various ways, either by providing social space for the public or through its ecological benefits.A series of regional and local elements and concepts that have been used in their design will continue to tie these projects to their historical context.

Design and Planning of Projects: Future Dilemmas and Prospects

Becoming the integral core of recent urban developments, urban landscapes have not only established a new relationship between the landscape and city but have also emphasised the public park/landscape as the focal point in Middle Eastern cities undergoing modernisation.While neoliberal politics have been transforming the public domain in capital cities into exclusive commercially driven landscapes5)[5]56, the radical and rapid evolution of large cities and their territories has spurred efforts to provide recreational public space and green retreats to counterbalance the concrete modern metropolis[7]9.

As urban planner Thomas Sieverts explains,cultural awareness is a minimum requisite for aesthetic awareness, so current urban design should incorporate techniques and procedures to encourage this awareness[10].Urban landscapes should emphasise involvement, experience, and a personal relation to the space, which range from contemplation to appropriation[8]29, while supporting cohabitation, blending different urban environments at the appropriate scale, and include zones of negotiation[8]28.They should also maintain a high level of accessibility for all income groups and be open to changing individual and collective rhythms[11].Due to its environmental, ecological,and aesthetic aspects, the landscape should be treated by decision-makers both as a physical entity and as a cultural construct, while responding to basic problems such as air or water pollution, or even waste management[12]219.In short, the quality of urban landscapes can be improved by integrating natural and urban systems[8]32.

Any new landscape project should not only enhance people's lives - it should also celebrate the history of the city and region by communicating tradition and memory through design6)[13].The concern is that most agencies in charge of forming urban neighbourhoods or public spaces in the Middle East do not often incorporate aesthetic or ethical issues in public decision-making[14]116involving the planning,design, and management of landscapes[14]117.A comprehensive understanding of urban landscapes requires an in-depth analysis of their impact on the formation and development of neighbourhoods, open spaces, and urban parks- and their collective social purposes.Instead of merely importing ideas from the West, the participation of local architects and designers has facilitated the application of the local, native,and indigenous landscape as potential models or sources of inspiration[15]75.Yet, as architects,landscape architects, and urban designers have progressively become more compartmentalised in their approaches, there is a pressing need for trans-disciplinary collaboration on both physical and cultural landscape[16]122.

在当代景观的设计中,另一个需要考虑的关键因素是当地的历史与传统。本土的专业人员及学者正在从更加批判性的视角,重新审视那些来自西方的曾经倍受称颂和学习的概念。对于该地区的多元文化遗产的兴趣不断提升——尤其是在普通民众与非政府组织层面——这促使公众更为关注城市项目带来的环境与文化益处。中东地区的城市景观已从一种仅供消遣的被动布景,转变为市民参与的活跃剧场。这一类新型空间与日常生活的真实韵律交相呼应。它们由此成为一种媒介,连接和支持着拥有不同规模和层级影响力的各类场所、人群及活动[8]32。它们能够通过多种多样的连接方式及不同尺度的交通基础设施,帮助整合城市中的孤立区和飞地[8]45。

当代大城市的密度不断提升,也就需要重新调整那些过时的基础设施及废弃场地的用途,例如一些弃用军事设施[7]6。建在荒地上的阿兹哈尔公园就是个很成功的例子,它给开罗市民的生活带来了实质性的改变(图6)。这个公园紧邻历史街区,不仅提升了低收入群体的生活品质,也给当地旅游及经济带来支持。尽管有些旅游导向的项目在宣扬一种东方主义的怀旧审美,将历史街区作为凝固的、不朽的遗存,但也有另一些项目能够认可城市、文化和居民的持续演化。例如约旦的索尔特历史城市景观项目,开发者尤其注重挖掘它成为一个旅游目的地的长期潜力,也竭力推广该地区的旅游基础设施和服务(图7)。在这个案例中,城市更新政策的设计也试图同时促进旅游发展和历史城市肌理的保护。实际上,旅游正带来新的自发性社会活动,这种活动不一定是该区域的原生城市结构及碎片化生长所天生具有的[9]317。

6 阿兹哈尔公园,开罗,埃及/Al-Azhar Park, Cairo, Egypt(图片提供/Courtesy of Wikimedia, 2013)

7 索尔特历史城市的中心区域,约旦/Central Area of Al-Salt historic town, Jordan (图片提供/Courtesy of Kıvanc Kılınc,2019)

无论是作为城市或城郊的公共广场还是公园,当代景观项目正积极推动中东城市迈入新的时代——尤其是塑造一个尊重公众声音的社会文化。这些城市景观根植于该地区前现代时期的城市园林,正通过多样方式改善城市中的生活品质——不论是为公众提供社会活动空间,抑或是带来生态层面的利益。这些项目中运用的一系列地区性和当地化的元素和概念,也将持续将它们与城市历史文脉紧紧相连。

项目设计和规划:未来的困境及远景

城市景观作为近期城市发展的核心,不仅建立了景观和都市之间的新关系,也强化了公园和公共景观作为中东城市当下现代化进程的焦点地位。尽管新自由主义政治正在将资本主义城市的公共领域转变为纯粹的商业驱动景观4)[5]56,但大城市区剧烈迅速的变化还是促生了不少这样的尝试——提供休闲性的公共空间和绿化场地,以平衡钢筋混凝土的现代都市环境[7]9。

城市规划学者托马斯·希尔维茨提出,文化自觉是审美自觉的最低要求,因此当下的城市设计应采取相应的技术和策略来鼓励这种自觉性[10]。城市景观应强化介入、体验以及人与空间的关系——这种关系可以从内在的沉思到外化的使用[8]29——在支持共生状态的同时,融合恰当尺度的不同城市环境,也纳入相应的过渡空间[8]28。它们也应为不同收入群体保留高度的可达性,并接纳不断变化的个人或集体的生活节奏[11]。鉴于景观的环境、生态和审美作用,政策制定者应将景观同时视为一种物质实体和一种文化建构,并回应空气污染、水污染甚至是垃圾处理等基本问题[12]219。简言之,通过自然和城市系统的整合,城市景观的品质亦能得到提升[8]32。

任何新建的景观项目,不仅需要提升人民的生活质量,还应通过设计表达传统与记忆,为城市和区域的历史书写赞歌5)[13]。值得担忧的是,中东大部分负责塑造城市街区或公共空间的权力机构,并不将美学或道德因素纳入景观规划、设计和管理的决策过程[14]116-117。对于城市景观的全面理解,需要深入分析它们对街区、开放空间和城市公园的形成、发展及其集体社会诉求的影响。当地建筑师和设计师的参与,不再仅仅从西方借取概念,而是将当地的、本土的和原生的景观作为潜在的概念模型或灵感源泉[15]75。不过,由于建筑师、景观设计师与城市设计师的路径正变得愈发不同,在物质与文化景观塑造过程中的跨学科合作也变得愈发紧迫[16]122。

我们亟需理解一座城市在历史进程中是如何被规划、建造和使用的——这3 个因素具有同等的重要性[17]14。未来的城市设计及规划实践,应运用生态反馈的、环境可持续的、社区参与的城市绿化策略,以优先考虑城市中的自然和绿色区域6)[5]70。在城市景观中,寻求一条规划、设计、开发与管理的整体性路径不能满足于纸上的空中楼阁。城市景观应该通过提升社区的观念,以形成并维持场所感。城市景观在设计和评估中,应作为城市基础设施的根本性要素,而非表面化装饰。最重要的是,城市景观是一件必需品。□

致谢:本文是我发表于《中东城市景观》(穆罕默德·加里普尔编著,Routledge,2016)引言部分的概要。在此感谢我的朋友和同事科万茨·科林茨博士,感谢他的邀约和宝贵意见。

It is important to understand how a city is planned, constructed, and utilised over time -and these three factors are equally important[17]14.Future urban design and planning efforts should prioritise nature and green areas in the city by utilizing ecologically-informed, environmentallysustainable, and community-inclusive urban greening initiatives7)[5]70.A holistic approach to planning,design, development, and management of urban landscapes is not limited to a picturesque framework.Urban landscapes should generate and protect the sense of place by enhancing the notion of community.They should be designed and evaluated as an essential component of the urban infrastructure, rather than a superfluous ornament.The urban landscape is, first and foremost, a necessity.□

Acknowledgement: This paper is a summary of my introduction published in Urban Landscapes of the Middle East (Edited by Mohammad Gharipour,Routledge, 2016).I would like to thank my friend and colleague, Dr.Kıvanç Kılınç, for his invitation and feedback on this essay.

注释/Notes

1)“伊斯兰花园”的发展并非局限于中东地区的边界。过去20年间,数个伊斯兰风格的园林设计项目在中东以外的地区落成。此种现象,笔者称其为“伊斯兰花园的移居”,在世界其他地区充当了中东地区的代表。/The development of the "Islamic garden" has not been limited to the boundaries of the Middle East.Over the last two decades several Islamicinspired gardens have been designed outside the Middle East.This phenomenon, which I call "Islamic gardens in diaspora", serves as a representative of this region in other parts of the world.

2)位于海法的巴布尔花园就是一个例子,该花园只在每周特定时段对朝圣者和游客开放。尽管该花园没有完全投入于日常城市文化,它的存在无疑对海法的城市设计产生影响,因为它在宏观尺度上创造了视觉和空间的连续性。/One such example is the Baha'i Garden in Haifa, which is open only to pilgrims and tourists at certain times of the week.Although this garden is not fully engaged in daily urban culture,its presence is clearly felt in Haifa's urban design because it creates visual and spatial continuity on the macro scale.

3)最近的学术文献证实近期的沙漠化是人类活动与气候变化的结果。/Recent academic literature confirms that recent desertification is the result of human activities and climate change.

4)更多信息详见参考文献[6]/For more information,refer to Reference [6]23-37.

5)Jala Makhzoumi, "The Greening Discourse:Ecological Landscape Design and City Regions in the Mashreq", Urban Design in the Arab World:Reconceptualizing Boundaries.详见参考文献/Refer to Reference [5]56.

6)皮尔斯·刘易斯(1975)称其为“场所精神”。详见参考文献[13]。/It is called by Pierce Lewis (1975)"the spirit of place". Refer to Reference [13].

7)Jala Makhzoumi, "The Greening Discourse:Ecological Landscape Design and City Regions in the Mashreq", Urban Design in the Arab World:Reconceptualizing Boundaries.详见参考文献/Refer to Reference [5]70.

参考文献/References

[1] EMAMI F.Urbanism of Grandiosity: Planning a New Urban Centre for Tehran (1973-76)[J].Islamic Architecture, March 2014,3(1):69-102.

[2] TÜRELI I.'Small' Architectures, Walking and Camping in Middle Eastern Cities[J].Islamic Architecture, January 2013,2(1):5-38.

[3] SOJA E W.Seeking Spatial Justice[M].Minneapolis:University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

[4] BRESHNA Z.A Program for the Rehabilitation and Development of Kabul's Historic Center[M]//MUMTAZ B., NOSCHIS K.(ed.).Development of Kabul: Reconstruction and Planning Issues, Lausanne,Switzerland: Comportements, 2004: 23-49.

[5] SALIBA R.(ed.).Urban Design in the Arab World:Reconceptualizing Boundaries.London: Ashgate.

[6] CUGURULLO F.How to Build a Sandcastle: An Analysis of the Genesis and Development of Masdar City[J].Journal of Urban Technology, 2013, 20 (1).

[7] SECCHI B.Wasted and Reclaimed Landscapes -Rethinking and Redesigning the Urban Landscape.Places, 2007, 19 (1): 6-11.

[8] CLEMMENSEN T J, NIELSEN T, DAUGAARD M.Qualifying Urban Landscapes[J].Journal of Landscape Architecture, 2010, 5 (2):24-39.

[9] KHIRFAN L.Ornamented Façades and Panoramic Views: The Impact of Tourism Development on al-Salt's Historic Urban Landscape[J].International Journal of Islamic Architecture, July 2013,2 (2):307-324.

[10] SIEVERTS T.Where we Live Now[M]// STADLER M.(ed.) Where We Live Now: An Annotated Reader.Suddenly Publishing, 2008:21-81.

[11] VIGANO P.On Porosity[C]// ROSEMANN J.(ed.).Permacity.International Forum on Urbanism, 2007.

[12] MAKHZOUMI J M.Landscape in the Middle East: An Inquiry.Landscape Research, August 2010,(27)3:213-228.

[13] LEWIS P F.To Revive Urban Downtowns, Show Respect for the Spirit of Place.Smithsonian, September 1975:32-41.

[14] SANCAR F H.Towards Theory Generation in Landscape Aesthetics[J].Landscape Journal, Fall 1985,4 (2):116-124.

[15] HELPHAND K.Dreaming Gardens: Landscape Architecture and the Making of Modern Israel[J].Landscape Journal, January 2003, 22 (2):73-86.

[16] SPIRN A W.The Poetics of City and Nature:Towards a New Aesthetic for Urban Design[J].Landscape Journal, Fall 1988:108-126.

[17] BLACKMAR E.The Urban Landscape[J].Journal of Architectural Education, September 1976, 30 (1):12-14.

[18] MAKHZOUMI J., PUNGETTI G.Ecological Landscape Design and Planning, The Mediterranean Context[M].London: Taylor & Francis Press, 1999.

[19] GHARIPOUR M.Persian Gardens and Pavilions:Reflections in History, Poetry and Arts[J].London: I.B.Tauris, 2013.

[20] GHARIPOUR M.(ed.) Urban Landscapes of the Middle East.London: Routledge, 2016.