Pleural effusion and ascites in extrarenal lymphangiectasia caused by post-biopsy hematoma: A case report

Qiong-Zhen Lin, Hui-En Wang, Dong Wei, Yun-Feng Bao, Hang Li, Tao Wang

Qiong-Zhen Lin, Department of Nephrology, The Third Hospital of Hebei Medical University,Shijiazhuang 050051, Hebei Province, China

Hui-En Wang, Department of Thoracic Surgery, Hebei Provincial General Hospital,Shijiazhuang 050051, Hebei Province, China

Dong Wei, Department of Urology, Hebei Provincial General Hospital, Shijiazhuang 050051,Hebei Province, China

Yun-Feng Bao, Department of Medical Imaging, Hebei General Hospital, Shijiazhuang 050051,Hebei Province, China

Hang Li, Department of Nephrology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Beijing 100045,China

Tao Wang, Department of Nephrology, The First Hospital of Hebei Medical University,Shijiazhuang 050000, Hebei Province, China

Abstract BACKGROUND The renal system has a specific pleural effusion associated with it in the form of“urothorax”, a condition where obstructive uropathy or occlusion of the lymphatic ducts leads to extravasated fluids (urine or lymph) crossing the diaphragm via innate perforations or lymphatic channels. As a rare disorder that may cause pleural effusion, renal lymphangiectasia is a congenital or acquired abnormality of the lymphatic system of the kidneys. As vaguely mentioned in a report from the American Journal of Kidney Diseases, this disorder can be caused by extrinsic compression of the kidney secondary to hemorrhage.CASE SUMMARY A 54-year-old man with biopsy-proven acute tubulointerstitial nephropathy experienced bleeding 3 d post hoc, which, upon clinical detection, manifested as a massive perirenal hematoma on computed tomography (CT) scan without concurrent pleural effusion. His situation was eventually stabilized by expeditious management, including selective renal arterial embolization. Despite good hemodialysis adequacy and stringent volume control, a CT scan 1 mo later found further enlargement of the perirenal hematoma with heterogeneous hypodense fluid, left side pleural effusion and a small amount of ascites. These fluid collections showed a CT density of 3 Hounsfield units, and drained fluid of the pleural effusion revealed a dubiously light-colored transudate with lymphocytic predominance (> 80%). Similar results were found 3 mo later, during which time the patient was free of pulmonary infection, cardiac dysfunction and overt hypoalbuminemia. After careful consideration and exclusion of other possible causative etiologies, we believed that the pleural effusion was due to the occlusion of renal lymphatic ducts by the compression of kidney parenchyma and, in the absence of typical dilation of the related ducts, considered our case as extrarenal lymphangiectasia in a broad sense.CONCLUSION As such, our case highlighted a morbific passage between the kidney and thorax under an extraordinarily rare condition. Given the paucity of pertinent knowledge, it may further broaden our understanding of this rare disorder.

Key Words: Urothorax; Pleural effusion; Perirenal hematoma; Renal lymphangiectasia;Lymphatic drainage; Case report

INTRODUCTION

The renal system has a specific pleural effusion associated with it in the form of“urothorax”, a condition where obstructive uropathy or occlusion of the lymphatic ducts leads to extravasated fluids (urine or lymph) crossing the diaphragmviainnate perforations or lymphatic channels[1]. In rare cases, this pleural effusion may be caused by renal lymphangiectasia, which is a congenital or acquired disorder of the lymphatic system of the kidneys[2]. The exact etiology of this disorder remains unknown, whereas the most common hypothesis is the occlusion of draining lymphatic ducts secondary to trauma, scarring, infection, inflammation or malignant cells of the kidneys[3]. There is only one report from the American Journal of Kidney Diseases[4]describing extrinsic compression of the kidney by hemorrhage leading to extrarenal lymphangiectasia, and we hereby described such an extremely rare case with resultant pleural effusion. The study was approved by our institutional review board (No. 2020-22), and written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 54-year-old man was admitted for serum creatinine (Scr) elevation for 1 mo.

History of present illness

He initially visited a local clinic due to loss of appetite and was found to have an elevated Scr without dysuresia. Fluid infusion had indiscernible effect on the abnormal Scr and no evidence of secondary kidney disease was found. He was then referred to us, pending renal biopsy.

History of past illness

The patient was a capable farm handex antewithout a known medical history.

Personal and family history

He denied any family history of hypertension, diabetes or kidney disease.

Physical examination

On arrival, his blood pressure was 150/90 mmHg, and he had a slightly anemic complexion. Otherwise, physical examination yielded no remarkable findings.

Laboratory examinations

Laboratory tests revealed a hemoglobin concentration of 108 g/L (reference: 130-150 g/L), platelet count of 202 × 109/L (100-300 × 109/L), plasma albumin of 41.3 g/L, Scr of 679.1 μmol/L (44.2-132.6 μmol/L), normal coagulation function including D-dimer and negative results for anti-nuclear antibody, anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibody and immunofixation electrophoresis. Screening for hepatitis B and malignancy was negative. After the routine workup, renal biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of acute tubulointerstitial nephropathy.

Imaging examinations

Plain chest X-ray was clear. Furthermore, the kidneys appeared normal on sonography without aberrant echogenicity.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Acute tubulointerstitial nephropathy.

TREATMENT

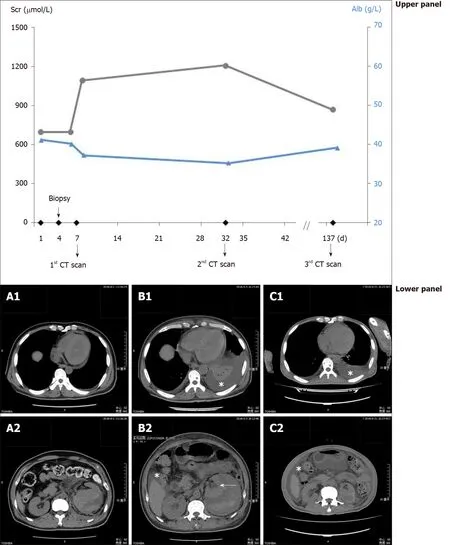

Three days after the biopsy, however, the patient experienced bleeding, which, upon clinical detection, manifested as a large perirenal hematoma without concurrent pleural effusion (Figure 1A). Laboratory testspost hocshowed a surge in the Scr level to 1094.3 μmol/L (Figure 1, upper panel), whereas the hemoglobin concentration,platelet count and plasma albumin were 56 g/L, 166 × 109/L and 36.7 g/L,respectively. Continuous renal replacement therapy was employed due to transient oliguria, and the patient’s situation was eventually stabilized by expeditious management, including selective renal arterial embolization.

While with good hemodialysis adequacy and under stringent volume control for Page kidney, computed tomography (CT) scan 1 mo later found further enlargement of the perirenal hematoma with heterogeneous hypodense fluid, massive left-sided pleural effusion and a small amount of ascites (Figure 1B). These fluid collections had a CT density of 3 Hounsfield units (HU), and drained fluid of the pleural effusion yielded a light-colored transudate with lymphocytic predominance (> 80%).Additionally, Scr remained elevated, and plasma albumin was generally stable, with a hemoglobin concentration of 97 g/L and platelet count of 240 × 109/L. Furthermore,the pleural effusion and ascites consistently showed the same HU and lymphatic nature 4 mo later (Figure 1C), accompanied by lowering of the Scr and rise in the albumin. Of note, the patient was free of pulmonary infection and cardiac dysfunction during the whole episode.

Figure 1 Evolution of the perirenal hematoma, pleural effusion and ascites in parallel with the corresponding serum creatinine and plasma albumin. Upper panel: Values of serum creatinine (circles connected by black lines) and plasma albumin (triangles connected by blue lines) at different time points; Lower panel: A: Computed tomography scan shortly after the detection of hemorrhage showing perirenal hematoma (A2), without pleural effusion (A1); B:Perirenal hematoma and small amount of ascites (B2), with pleural effusion (B1, asterisk) 1 mo after the hemorrhage, the compressed kidney is also visible (B2,arrow); C: Perirenal fluid retention and ascites (C2), with pleural effusion (C1, asterisk) 5 mo after the hemorrhage. Alb: Albumin; CT: Computed tomography; Scr:Serum creatinine.

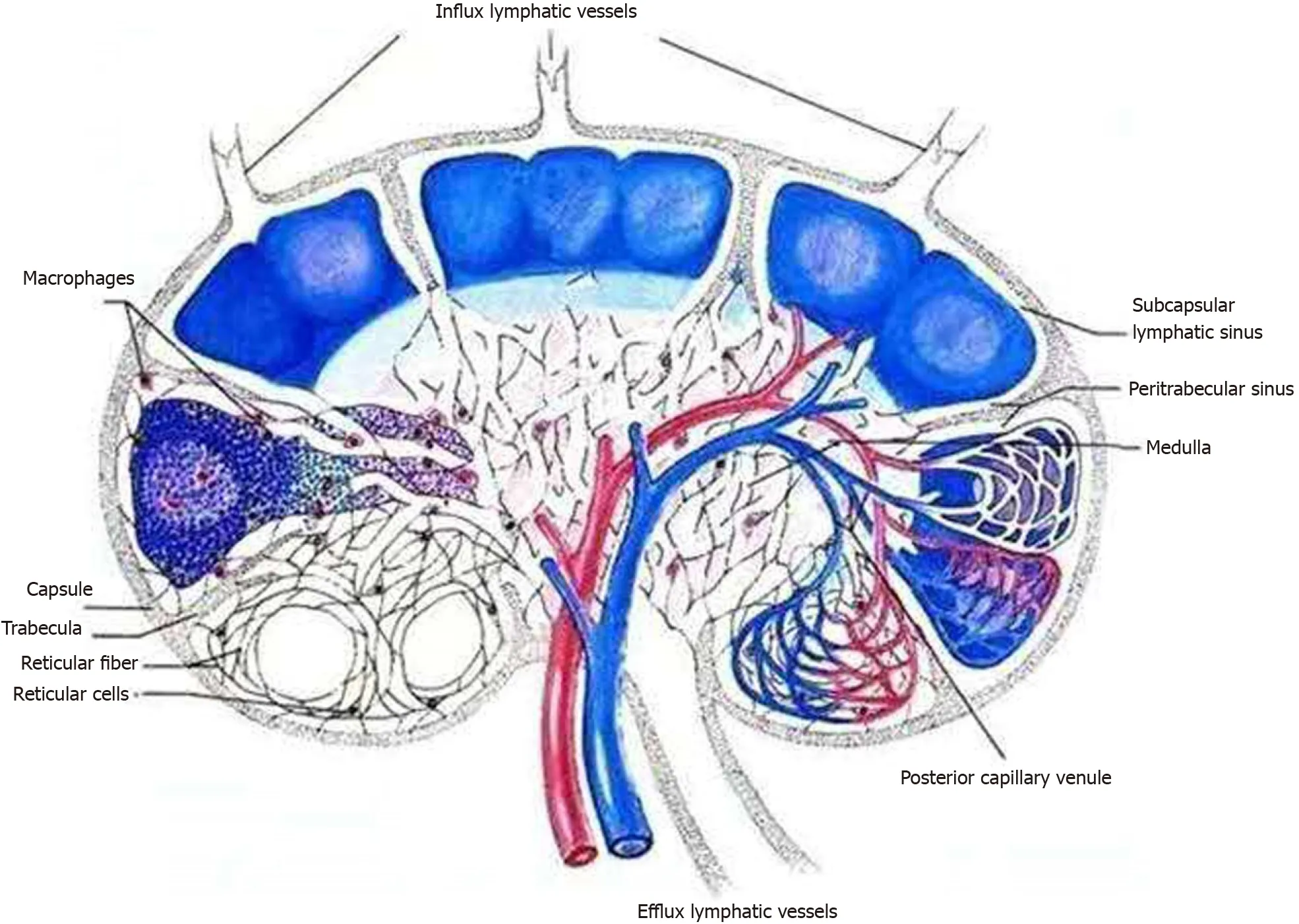

As schematically outlined in Figure 2, tight compression of the renal parenchyma may keep the draining lymphatic vessels shut but not prevent the inflow from the capsular lymph plexus. On the basis of clinical features, imaging findings and laboratory tests, the diagnosis of extrarenal lymphangiectasia was made, as classified previously[4]. The patient was then kept on hemodialysis, with a special focus on dry weight and urinary volume.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Figure 2 Schematic showing the flow of renal lymphatic fluid. Inflow from the capsular lymph plexus went through the renal parenchyma via subcapsular and peritrabecular lymphatic sinuses and pericapillary space and eventually made confluence at the efflux lymphatic vessels for out-draining.

He was eventually detached from hemodialysis 10 mo after the hemorrhage and treated for chronic kidney disease stage 5, according to the “Kidney Disease:Improving Global Outcomes” Guideline[5]. His Scr fluctuated between 300-400 μmol/L and had a daily urinary volume of approximately 1000 mL.

DISCUSSION

Renal lymphangiectasia is a rare benign disorder characterized by abnormal and ectatic lymphatic vessels within and around the kidneys. The abnormal dilatation of these lymphatic ducts arises from their failure to communicate with larger retroperitoneal lymph vessels. Although it is bilateral in nature in more than 90% of cases[2], this disorder may also be unilateral or focal[6]. The diagnosis is based mainly on imaging results, although perinephric/pleural fluid analysis and kidney biopsy are definitely helpful[2,4]. As such, imaging findings of renal lymphangiectasia may include peripelvic cysts (intrarenal lymphangiectasia) and perinephric fluid collections(extrarenal lymphangiectasia)[4,7]. However, locular cystic lesions within the renal sinuses may be absent in cases of perirenal compression of the kidney parenchyma or bilateral renal vein thrombosis[8,9]. In addition to the perinephric and/or retroperitoneal fluid collection, it may also manifest ascites and, rarely, pleural effusion.

Renal lymphangiectasia may confer pleural effusion through the passage of“urothorax”. Under such circumstances, pleural drainage usually reveals chylous fluid with lymphocytic predominance (≥ 90%)[4], while occasionally, cell staining may prove colorless at gross examination[2]. In another chance encounter supporting this finding,we recently admitted another patient on maintenance peritoneal dialysis for dyspnea on exertion. His discomfort was exacerbated after the infusion of peritoneal dialysate,and a CT scan found a large amount of right-sided pleural effusion (Supplementary Figure 1). After the addition of methylene blue to the dialysate, colored pleural drainage was observed. Indeed, urinary tract infection may spread upward and lead to lung abscess[10]. Taken together, our case highlighted ade novomorbific passage between the kidney and thorax under extraordinary conditions.

Clinically, renal lymphangiectasia is usually asymptomatic and incidentally diagnosed. When symptomatic, the most common presentations are abdominal pain(42%) and abdominal distension (21%), followed by fever, hematuria, fatigue, weight loss, hypertension and occasional deterioration in renal function[11]. A unique entity,namely, the Page kidney, was considered in this case with the associated hypertension after subcapsular hematoma, and the management required sufficient fluid control[12].In this respect, our patients on maintenance hemodialysis generally manifested good Kt/V in both a cross-sectional study[13]and 10-year follow-up[14], and the critically ill patients receiving continuous renal replacement therapy had fine volume control[15].Therefore, it is highly unlikely that the observed pleural effusion was derived from fluid overload. Of essential importance, caution regarding polycythemia and the associated deep venous thrombosis has been recommended in renal lymphangiectasia[2]. In this regard, a detailed description of the differential diagnosis[2]and therapeutic approach[4]is available elsewhere.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we reported an extremely unusual case of pleural effusion caused by extrarenal lymphangiectasia, which resulted from occlusion of the lymphatic ducts due to compression of the renal parenchyma by a hematoma. Given the paucity of pertinent knowledge, these findings may further improve our understanding of this rare disorder.

World Journal of Clinical Cases2020年24期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2020年24期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Primary duodenal tuberculosis misdiagnosed as tumor by imaging examination: A case report

- Successful endovascular treatment with long-term antibiotic therapy for infectious pseudoaneurysm due to Klebsiella pneumoniae: A case report

- Idiopathic adulthood ductopenia with elevated transaminase only: A case report

- Takotsubo cardiomyopathy associated with bronchoscopic operation: A case report

- Extracorporeal shock wave therapy treatment of painful hematoma in the calf: A case report

- Rare case of drain-site hernia after laparoscopic surgery and a novel strategy of prevention: A case report