Novel triple therapy for hemorrhagic ascites caused by endometriosis: A case report

Xue Han, Shi-Tai Zhang

Xue Han, Shi-Tai Zhang, Gynecology Department, Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang 110004, Liaoning Province, China

Abstract BACKGROUND Massive hemorrhagic ascites caused by endometriosis is exceedingly rare, and the treatment strategy remains controversial. Here, we report a case of endometriosis with massive hemorrhagic ascites treated with a novel triple therapy including conservative surgery, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist, and then dienogest.CASE SUMMARY A 28-year-old nulliparous patient was admitted to Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University, and exploratory laparoscopy was performed. A total of 9500 mL of brown ascites was aspirated from the pelvic cavity, the bilateral ovaries strongly adhered to the posterior of the uterus and were fixed to the pelvic floor,and endometriotic cysts were not observed in either ovary. The pelvic and abdominal peritonea were covered with patchy red, white, and brown endometriotic lesions and defects. Partial surgical resection of endometriotic lesions on the peritoneum was performed while we simultaneously collected multiple peritoneal biopsies. The final pathological diagnosis was endometriosis coupled with hemorrhagic necrotic tissue.CONCLUSION Postoperative injection of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist was provided three times, followed by dienogest administration, and we will continue to follow up with this ongoing treatment.

Key Words: Endometriosis; Hemorrhagic ascites; Novel triple therapy; Dienogest;Recurrence; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Endometriosis is a chronic gynecological disorder caused by the presence of endometrial tissue outside the uterine cavity, and typically involves the peritoneum,ovaries, and rectovaginal septum. This is a relatively common disorder estimated to affect 6.1%-10.0% of women of reproductive age and is associated with chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, and infertility[1]. Ascites is the pathological accumulation of fluid in the peritoneal cavity usually caused by liver or kidney disease, heart failure, and other conditions. Gynecological disorders such as ovarian cancer, ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, and Meigs syndrome can also lead to ascites[2].Furthermore, ectopic pregnancy and ovarian rupture can cause hemorrhagic ascites,where ascites fluid contains more than 50000 red blood cells/mm3.

Endometriosis presenting with hemorrhagic ascites is extremely rare in clinical settings. In 1954, Brews reported the first case of endometriosis with ascites and in 2011, Gungoret al[3]published a systematic review analyzing 63 cases of endometriosis with ascites[3]. As of 2014, a total of 76 cases have been reported in the literature, and the majority of those cases were in nulliparous patients from Asia and Africa[4].

We report on a case of endometriosis with massive hemorrhagic ascites in a nulliparous African patient. The patient also experienced secondary anemia and repeated recurrence of ascites following conservative drug treatment, and opted to undergo surgical intervention. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University and implemented in accordance with approved guidelines.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 28-year-old nulliparous Nigerian patient developed symptoms of bloating,osteoporosis, and hypercoagulopathy. Given these persistent symptoms, the patient opted for further treatment at Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University.

History of present illness

One year ago, the patient was admitted to the First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University with increasing abdominal circumference and distension[5].Ultrasonography-guided omental biopsy was performed, and the pathological diagnosis was endometriosis. The patient had chosen a conservative drug treatment due to her age and desire to retain reproductive options for the future. During treatment with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist (GnRH-a) and oral contraceptives, puncture aspiration was required every 3–4 mo to reduce ascites.

History of past illness

The patient had a free previous medical history.

Personal and family history

The patient had a free personal and family history.

Physical examination

The patient’s temperature was 36.5 °C, heart rate was 86 bpm, respiratory rate was 16 breaths per minute, blood pressure was 135/75 mmHg, and oxygen saturation in room air was 99%. The abdomen is obviously bulging, and the abdominal circumference was 85 cm.

Laboratory examinations

After admission, CA-125 (carbohydrate antigen 125) in serum was 36.42 U/mL, which slightly exceeded the reference range of 0-35 U/mL, while other serum test results were normal. However, CA-125 in ascites was 3058 U/mL, and although ascites was considered to be exudate, no tumor cells were detected in the collected fluid.

Imaging examinations

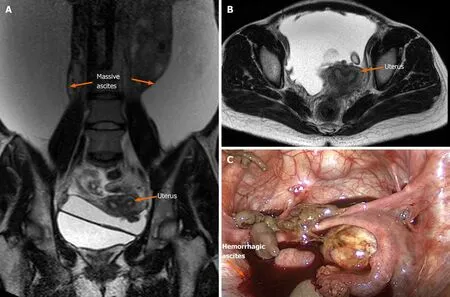

Ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging revealed a large amount of ascites,but no obvious mass was observed in the abdominal cavity (Figure 1A and B).Magnetic resonance imaging showed slight invagination of the fundus uteri, which proceeded to combine with bicornuate uterus. Hysteroscopy was not performed as per the patient’s preference. Anal examination revealed that the Douglas cavity was closed, and a few painful nodules could be felt.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The final diagnosis of the presented case was hemorrhagic ascites caused by endometriosis.

TREATMENT

We assembled a multi-disciplinary team prior to surgery, in which specialists in medical imaging and gynecological oncology were invited to participate. Laparoscopic surgery was deemed useful, not only to explore the extent and degree of the lesion but also to exclude malignant metastasis by multiple biopsies.

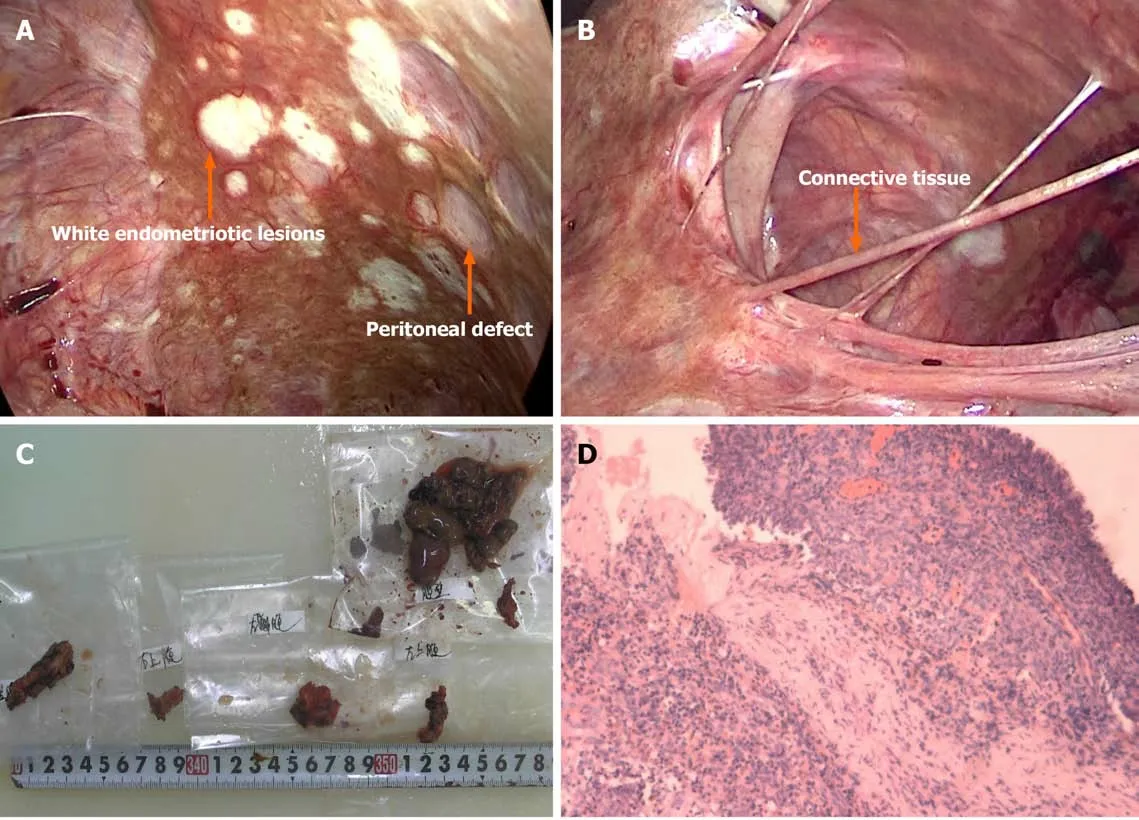

Considering the ascites recurrence and the patient’s desire to retain reproductive options, we proceeded with laparoscopic partial resection of endometriosis and multiple biopsies to preserve the uterine and bilateral adnexa. A total of 9500 mL of brown ascites was aspirated from the pelvic cavity, and large amounts of coagulated blood adhering to the pelvic peritoneum was observed through a laparoscope. The bilateral ovaries strongly adhered to the posterior of the uterus and were fixed to the pelvic floor, causing complete closure of the Douglas cavity. Endometriotic cysts were not observed in either ovary (Figure 1C). The pelvic and abdominal peritonea were covered with patchy red, white, and brown endometriotic lesions and defects(Figure 2A). All surfaces of abdominal organs such as the liver, spleen, and gastrointestinal tract were covered with tough connective tissue, and a portion of the jejunum-ileum and colon had adhered to the left abdominal wall (Figure 2B).

Partial surgical resection of endometriotic lesions on the peritoneum was performed while we simultaneously collected multiple peritoneal biopsies. The final pathological diagnosis was endometriosis coupled with hemorrhagic necrotic tissue (Figure 2C and D). Postoperative injection of GnRH-a 0 was provided 3 d after surgery, and has continued at 28-d intervals during the second and third months postoperatively,followed by dienogest (DNG) (2 mg, daily taken orally) administration, and this course of treatment is planned to continue upon follow-up.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient is currently recovering well and had no recurrence during 1 year of followup.

DISCUSSION

Figure 1 Bilateral ovaries were adhered to the posterior of the uterus, and endometriotic cysts were not observed in either ovary. A and B:Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a large amount of ascites, and slight invagination of the fundus uteri, which proceeded to combine with bicornuate uterus; C:Large amount of brown ascites and coagulated blood were observed in the pelvic cavity.

Endometriosis is an estrogen-dependent disease, manifested by the existence and growth of functional endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus[5-7]. The pathogenesis of endometriosis is still unclear, and it is currently considered to be a heterogeneous disease caused by multiple factors[5,8]. Genetic studies have shown that endometriosis has a genetic tendency, however, this predisposition is complex[6]. Meanwhile, the epigenetic mechanisms underlying endometriosis involve many processes of the acquisition and maintenance of immunologic, immunohistochemical, histological, and biological aberrations that characterize the ectopic endometrium in patients who are affected by endometriosis[6,7].

Massive hemorrhagic ascites caused by endometriosis is exceedingly uncommon.Among the 63 cases reported by Gungoret al[3]in 2011, 38.1% also presented with pleural effusion[3].

Currently, the specific pathogenesis for this condition is unclear. Bernsteinet al[9]suggest that the rupture of ovarian endometriotic-cysts occurs, splashing contents such as endometrial cell and hemorrhagic fluid onto the surface of the pelvic organs and peritoneum. Capillaries distributed on the visceral and parietal peritoneum are damaged, followed by increased permeability, which could then cause a large amount of fluid and proteins to penetrate into the abdominal cavity. This would then lead to exudative ascites and adhesions. In addition, if severe pelvic adhesions block the absorption of fluid, ascites are further aggravated. As far as we are aware, endometrial rupture is a common pathology, usually accompanied by acute abdominal pain, slight fever, and a small amount of ascites. However, this fails to explain the appearance of massive ascites in this case and others. Average ascites volume in these cases is approximately 3.3 L, with even some recorded as high as 10 L[10]. Previous reports have also included two cases of hypovolemic shock due to this disease[11].

In this case, no obvious endometriotic cyst was found on the bilateral ovaries, but the pelvic peritoneal surface showed a scattered pattern of brown viscous tissue. At the same time, the ovaries and surrounding tissues were inflamed, which could have been caused by an earlier endometriotic cyst rupture (Figure 1B). We collected a total of 9500 mL of hemorrhagic ascites fluid during surgery, which then lead to the postoperative anemia. As for cases with pleural effusion, Bernsteinet alsuggested that the presence of pleural endometriosis or a mechanism similar to the development of Meigs syndrome may be the cause. However, there are many cases that do not share these characteristics; thus, the pathogenesis of ascites is still not fully explained.

Figure 2 The final diagnosis. A: The pelvic and abdominal peritonea were covered with patchy red, white, and brown endometriotic lesions and defects; B: All surfaces of abdominal organs were covered with tough connective tissue; C: Gross pathology of resected tissues; D: The final pathological diagnosis was endometriosis coupled with hemorrhagic necrotic tissue.

Abdominal distention and pain, anorexia, and menometrorrhagia are the most frequent clinical symptoms of endometriosis-related massive ascites[12]. Physical findings revealed that pelvic mass and nodularity were most common but appeared in only 35% and 20% of cases, respectively[3]. Serum CA-125 can have a minimum value of 7 U/mL and a maximum of 3504 U/mL in this condition[13]. Due to these nonspecific features, differential diagnoses for endometriosis-related should include ovarian cancer and pelvic or abdominal tuberculosis in order to avoid unnecessary treatment. Final diagnosis still requires histopathological examination. However,compared with previous laparoscopic surgery techniques or transabdominal surgery,core needle biopsy is a minimally traumatic method of fluid collection with a short recovery period[5,14].

Although superficial peritoneal lesions and ovarian endometriosis are the most common, deep invasive endometriosis and extrapelvic endometriosis are the challenges that we have to face, and the ascites caused by endometriosis mentioned in this case is also very difficult to treat[12].

As for the treatment of deep invasive endometriosis, medication is sometimes sufficient to relieve symptoms and signs in many patients, thorough surgery and even segmental intestinal resection are required in some patients, and neuroprotection and blood vessel preservation methods are used to restore normal pelvic anatomy and function[12,14]. To date, the treatment strategy for ascites related to endometriosis has been inconsistent[15]. However, such cases can be treated similarly to endometriosis,primarily using drugs or surgery to disrupt ovarian function. Interestingly enough,there were two cases where radiation therapy was effective from 1954 and 1957[3].According to previous case reports, 88.9% of the patients opted for surgeries, including transabdominal or laparoscopic salpingo-oophorectomy with or without total abdominal hysterectomy, and biopsy to confirm the histological diagnosis. A total of 14 patients underwent radical surgery (bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy) and none of them relapsed. In addition to the radical surgery, ascites recurrence was reported with all other surgical methods. However, prior reports indicated that the proportion of nulliparity is high (82%), and patients typically do not opt for radical surgery[3].

Drugs most commonly prescribed for conservative treatment include danazol,progesterone, and oral contraceptives. After 1970, the development of GnRH-a provided an alternative to conservative treatment[10]. Pharmaceutical treatments entail not only the risk of ascites recurrence, but also the side effects caused by long-term continuous medication, such as hot flashes, night sweats, and decreased bone mineral density. In 2014, Asanoet al[16]reported a case in which DNG was used to replace GnRH-a in the medical treatment of endometriosis-related ascites where diagnosis was confirmed by laparoscopic biopsy[16], no evidence of recurrence was observed at the 1-year follow-up, and this drug has recently been approved for use in China. In the present case, the patient was a young nulliparous woman who underwent surgical resection of all endometriotic lesions with retention of the uterine and bilateral adnexa.Adhesive prevention material and GnRH-a were adopted during and post-surgery,respectively. DNG is a novel drug in China, and will be implemented as an alternative treatment for this patient following the third application of GnRH-a[17].

To our knowledge, this is the first report of endometriosis-related massive ascites treated with a novel triple therapy, which includes conservative surgery, DNG, and GnRH-a, and the recurrence reduction and fertility promotion will be evaluated at future follow-ups.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, due to its rare incidence and unknown etiology, consensus has not been reached regarding the treatment principles and prognosis for endometriosis-related ascites. This issue warrants further research.

World Journal of Clinical Cases2020年23期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2020年23期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Discontinuous polyostotic fibrous dysplasia with multiple systemic disorders and unique genetic mutations: A case report

- Primary breast cancer patient with poliomyelitis: A case report

- Symptomatic and optimal supportive care of critical COVID-19: A case report and literature review

- Multiple ectopic goiter in the retroperitoneum, abdominal wall, liver,and diaphragm: A case report and review of literature

- Acute celiac artery occlusion secondary to blunt trauma: Two case reports

- Uncontrolled central hyperthermia by standard dose of bromocriptine: A case report