右美托咪啶对脑创伤患者脑血流的影响

盛阮妹 张宏泽

摘要:目的 比较右美托咪啶对于伴或不伴脑创伤的危重患者脑血流的影响。方法 非脑创伤患者15名与脑创伤患者20名分入CON和TBI组,所有患者接受1 ug kg-1的右美托咪啶静注10分钟,继之0.4 ug kg-1 h-1推注60分钟,多巴胺维持血压在用药前水平。于镇静前和镇静开始后70分钟测定脑血流(CBF)和脑代谢率(CMR)。结果 右美托咪啶显著减少CON组脑血流(差值=3.3 ml s-1, 95% CI=0.92–5.7 ml s-1, p=0.008),CMR和CMR/CBF无变化。TBI组右美托咪啶所致的CBF、CMR和CMF/CBF无明显改变。CON组CBF减少幅度大于TBI组(差值 = 13.9%, 95% CI = 5.5–22.2%, p=0.002).结论 右美托咪啶用于脑创伤患者对脑氧代谢无明显影响。

关键词:脑血流,脑代谢率,脑创伤

【中图分类号】R338 【文献标识码】A 【文章编号】2107-2306(2020)01-006-04

【Abstract】Objective To examine the effect of dexmedetomidine on CBF in critical ill patients with or without TBI. Methods Fifteen patients without TBI and 20 patients with TBI were assigned to CON or TBI groups, respectively. All patients received 1 ug kg-1 dexmedetomidine infused over 10 minutes, followed by a 0.4 ug kg-1 h-1 continuous infusion for 60 minutes. Blood pressure was maintained at the pre-sedation level with dopamine for all patients. The CBF and cerebral metabolic rate (CMR) were measured before sedation and 70 minutes after dexmedetomidine administration. Results Dexmedetomidine administration significantly decreased CBF in patients of the CON group (difference=3.3 ml s-1, 95% CI=0.92–5.7 ml s-1, p=0.008), without altering the CMR and CMR/CBF ratio. The dexmedetomidine-induced change of CBF, CMR and CMR/CBF was not significant in the TBI group. The percentage of CBF reduction was greater in the CON group than in the TBI group (difference = 13.9%, 95% CI = 5.5–22.2%, p=0.002). Conclusions Dexmedetomidine may be used in patients with TBI without risk of affecting brain oxygenation.

【KEY WORDS】Cerebral blood flow, cerebral metabolic rate, traumatic brain injury

脑创伤患者经常需要应用镇静剂以便抑制躁动,避免呼吸机对抗,控制颅内压1。然而镇静药物可能影响对患者神智评估,延长呼吸机使用和ICU滞留时间2。右美托咪啶(Dex)是高选择性α2受体拮抗剂,具有浅镇静、易唤醒,呼吸抑制小的特点3,尤其适合神经重症患者镇静的需要4,5。

大量研究显示Dex可减少实验动物6,7和健康志愿者8,9的脑血流(CBF),但其对脑创伤患者CBF的影响尚不清楚。对于脑血管自我调节功能受损的患者,Dex可降低血压从而减少CBF10,而其对脑代谢率的影响未知。动物实验显示Dex显著减少CBF,对CMR的影响则不大11,12。Drummond等9证实Dex可同时减少健康志愿者的CBF和CMR。有研究提示Dex可安全的用于神经损伤患者,但是并未报告其对患者CBF的影响3,13。

多种因素可能影响脑创伤患者的预后,CBF是其中最关键因素14。即便血压轻度降低也可能影响脑创伤患者死亡率15。Dex可因其抗交感作用而剂量依赖性的降低体循环血压,减少CBF16。对于脑创伤患者,该作用可能更明显,因为患者的腦血管自我调节功能受损17。Dex还可能收缩血管增加脑血管阻力,从而影响CBF8。但是对于脑血管收缩功能受损的脑创伤患者,该作用有多大影响尚不清楚14。我们认为对于脑创伤患者,当维持患者体循环血压稳定时,可防止Dex减少CBF。本研究中,我们比较了伴或不伴脑创伤患者,使用Dex镇静对CBF的影响。

1 资料与方法

1.1 一般资料

本研究经院伦理委员会批准,并在Current Controlled Trials网站注册(ISRCTN57998533)。患者入ICU后第二天进行评估,如果符合入选标准,则患者家属签署知情同意书后立即开始实验。

1.2 入选和排除标准

入选标准:1)年龄位于18-80岁之间;2)患者使用呼吸机。排除标准:1)孕妇;2)平均动脉压低于60 mmHg(非脑创伤患者)或者80 mmHg(脑创伤患者);3)肝肾功能障碍;4)实验当天使用过血管活性藥或者镇静药,或者其他可能影响CBF的药物;5)合并其它神经系统疾病的非脑创伤患者。

1.3 治疗方案

15名非脑创伤患者和20名脑创伤患者分别分入CON组和TBI组,所有的患者接受10分钟总量1ug kg-1的Dex,继之0.4 ug kg-1 h-1输注1小时,多巴胺维持患者血压于镇静前平均动脉压±5 mmHg水平。记录患者一般资料,镇静前和镇静70分钟时记录CBF数值,计算CMR和CMR/CBF数值,以及多巴胺使用量。

1.4 CBF测量

CBF测量采用多普勒超声技术测定颅外颈内动脉和椎动脉处血流18。采用7.5-MHz线阵探头的彩色超声系统(Esaote MyLab40, Naples, Italy)。患者仰卧,测量颈内动脉时头略微抬起并偏向对侧25-40度,在颈动脉分叉水平以上1.5 cm测量;测量椎动脉时头偏转10度,于C4和C5水平测量。所有测量由同一位超声医生使用同一台机器重复测量2次。CBF的减少值=(镇静前CBF-镇静中CBF)/镇静前CBF*100%。

1.5 CMR计算

CMR测定方法同前9。颈静脉血氧饱和度(SjvO2)测量,颈静脉采血速度不快于1.5 ml min-1。动脉血氧饱和度(SaO2)和二氧化碳分压(PaCO2)根据股动脉处血气分析值获得。CMR计算公式:CMR=CBF*(SaO2 ml-1-SjvO2 ml-1)。

研究的首要目标是镇静后CBF的变化,次要目前是CMR和CMR/CBF。

1.6 统计方法

正态分布的数据以均数±标准差及可信区间表示,采用团体t检验比较。分类数据以数量或中位数表示。采用SAS 8.0软件进行统计分析,p<0.05认为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果

2.1 患者基本情况

患者一般情况见表1。CON组所有患者实验前进行了腹部或者骨科手术。TBI组18名患者试验前进行了血肿清除术。

2.2 脑血流和脑氧代谢变化

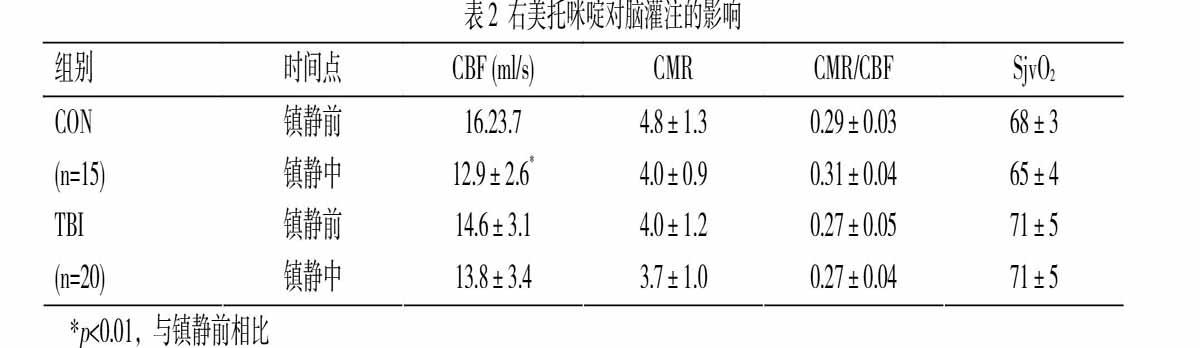

如表2所示,对于CON组患者,Dex减少CBF达19.6±9.6%(差值=3.3 ml s-1,95% CI=0.92-5.7 ml s-1,p=0.008)。TBI组Dex镇静期间CBF减少5.7±13.6%(差值=0.8 ml s-1,95% CI=-1.3-2.9 ml s-1,p=0.432)。两组之间CBF减少值差异显著(差异=13.9%,95% CI=5.5-22.2 ml s-1,p=0.002,图1)。

Dex对CON组(差值=0.7,95% CI=0.1-1.6)和TBI组(差值=0.3,95% CI=-0.4-1.1)患者的CMR影响都不明显(表2),两组之间CMR的变化值差异亦不明显(差值=7.7%,95% CI=-6.2%-21.7%,p=0.268,图1)。CON(差值=-0.02,95% CI=-0.05-0.01)和TBI组(差值=0.01,95% CI=-0.02-0.04)CMR/CBF比值在镇静前后的差异也不明显。

两组患者镇静前后SjvO2变化不明显。我们注意到TBI组镇静前CMR值低于CON组,而SjvO2高于CON组,虽然其差异未达统计学意义(表2)。

2.3 呼吸和循环变化

两组患者镇静前后的血压和心率无明显变化。呼吸指标如PaO2和PaCO2保持在镇静前水平(表3)。TBI组多巴胺用量为8.6±2.7 ug kg-1 min-1,较之CON组的6.2±3.7 ug kg-1 min-1明显增高(差值=2.4 ug kg-1 min-1,95% CI=0.2-4.6 ug kg-1 min-1,p=0.034)。

3 讨论

本研究观察了Dex对脑创伤患者CBF和CMR的影响。研究发现,Dex对脑创伤患者CBF的影响显著小于非脑创伤患者。如果保持血压平稳,Dex对患者CMR/CBF的比值也无明显影响。

Dex可用于短时间镇静而无明显呼吸抑制19。既往的研究提示Dex可通过多种机制发挥脑保护作用,作为脑损伤患者的镇静药物很有吸引力。Dex降低循环中的儿茶酚胺浓度,平衡脑的氧供与氧耗,减少兴奋性毒性,改善脑缺血部位灌注20,21。作为α2受体激动剂,Dex可促进星形胶质细胞的氧代谢,降低神经毒性递质谷氨酸的前体谷氨酰胺的含量22。其脑保护机制还有抑制异氟烷诱导的caspase-3表达23,从而调节促凋亡和抗凋亡蛋白的平衡24。

精确测量患者的血流量很困难,不同的方法都有其固有的缺陷25。电磁流量计被认为是测量血流量的金标准,然而其有创性和电离辐射影响其应用。经颅多普勒超声是临床监测脑灌注最常用的技术手段9,10。然而它只能提供血流流速信息,而不能提供血管几何形状和CBF方面的信息26。血流速度增加可能是动脉血管收缩和缺血的迹象。超声血流定量技术已研究多年,本研究利用频谱多普勒超声技术来估测血流量,之前的研究显示其系统误差为6%或更低27。

既往认为Dex会减少CBF,不适合用于脑损伤患者镇静19。其机制可能与降低体循环血压,以及收缩脑血管有关9,17。脑血管具有自主调节能力以对抗体循环血压变化,维持CBF稳定。脑创伤往往伴有脑血管损伤,这使得患者的CBF易于受到血压的影响14。因此,在Dex镇静期间防止体循环血压下降尤为重要。而且因为脑血管功能受损,我们怀疑Dex所致的脑血管收缩也可能不像在非脑创伤患者中那么明显。本研究中的结果也支持该假设,脑创伤患者Dex镇静期间CBF的减少程度明显低于对照组。多巴胺可诱发血管收缩,有研究显示α1受体激动剂收缩脑血管作用明显强于肾上腺素能受体28。

实验结果显示对于非脑创伤患者,Dex镇静导致的患者CMR下降幅度较大,但是两组患者镇静前后CMR的下降幅度都未达统计学差异。清醒患者往往伴有焦虑,镇静能够降低其脑代谢水平;而昏迷患者可能镇静药物对CMR的影响不明显。重要的是,镇静前后CMR/CBF的比值,以及SjvO2的水平變化都不明显,这提示无论是否合并脑创伤,Dex镇静并不会导致脑缺血。

本研究有一些缺陷。首先,研究中采用的多普勒超声测量血流量的方法精确度不高;其次本研究为单中心,研究对象数量较少;第三,本研究未评估颅内压和脑灌注压,它们对CBF有很大影响。有研究显示Dex对神经外科手术后患者的颅内压和脑灌注压无明显影响13。本研究未对患者的预后进行随访,以评估Dex镇静的安全性。

综上所述,Dex镇静时,脑创伤患者的CBF下降程度明显小于非脑创伤患者,亦不会引起CMR/CBF比值的改变。这些结果提示脑创伤患者应用Dex镇静是安全的。未来需要进一步研究Dex影响CBF的机制,以及更大样本的研究对象和更长的随访时间。

参考文献:

[1] Roberts DJ, Hall RI, Kramer AH, et al. Sedation for critically ill adults with severe traumatic brain injury: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Critical Care Medicine 2011;39:2743–51.

[2] Strom T, Martinussen T, Toft P. A protocol of no sedation for critically ill patients receiving mechanical ventilation: A randomised trial. Lancet 2010;375:475–80.

[3] Grof TM, Bledsoe KA. Evaluating the use of dexmedetomidine in neurocritical care patients. Neurocritical Care 2010;12:356–61.

[4] Mirski MA, Lewin 3rd JJ, Ledroux S, et al. Cognitive improvement during continuous sedation in critically ill, awake and responsive patients: The Acute Neurological ICU Sedation Trial (ANIST). Intensive Care Medicine 2010;36:1505–13.

[5] Tang JF, Chen PL, Tang EJ, et al. Dexmedetomidine controls agitation and facilitates reliable, serial neurological examinations in a non-intubated patient with traumatic brain injury. Neurocritical Care 2011;15:175–81.

[6] Chi OZ, Hunter C, Liu X, et al. The effects of dexmedetomidine on regional cerebral blood flow and oxygen consumption during severe hemorrhagic hypotension in rats. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2011;113:349–55.

[7] Nakano T, Okamoto H. Dexmedetomidine-induced cerebral hypoperfusion exacerbates ischemic brain injury in rats. Journal of Anesthesia 2009;23:378–84.

[8] Prielipp RC, Wall MH, Tobin JR, et al. Dexmedetomidine-induced sedation in volunteers decreases regional and global cerebral blood flow. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2002; 95:1052–9.

[9] Drummond JC, Dao AV, Roth DM, et al. Effect of dexmedetomidine on cerebral blood flow velocity, cerebral metabolic rate, and carbon dioxide response in normal humans. Anesthesiology 2008;108: 225–32.

[10] Ogawa Y, Iwasaki K, Aoki K, et al. Dexmedetomidine weakens dynamic cerebral autoregulation as assessed by transfer function analysis and the thigh cuff method. Anesthesiology 2008;109:642–50.

[11] McPherson RW, Koehler RC, et al. Intraventricular dexmedetomidine decreases cerebral blood flow during normoxia and hypoxia in dogs. Anesthesia & Analgesia 1997;84:139–47.

[12] Karlsson BR, Forsman M, Roald OK, et al. Effect of dexmedetomidine, a selective and potent alpha 2-agonist, on cerebral blood flow and oxygen consumption during halothane anesthesia in dogs. Anesthesia & Analgesia 1990;71:125–9.

[13] Aryan HE, Box KW, Ibrahim D, et al. Safety and efficacy of dexmedetomidine in neurosurgical patients. Brain Injury 2006;20:791–8.

[14] DeWitt DS, Prough DS. Traumatic cerebral vascular injury: The effects of concussive brain injury on the cerebral vasculature. Journal of Neurotrauma 2003;20:795–825.

[15] Chesnut RM, Marshall LF, Klauber MR, et al. The role of secondary brain injury in determining outcome from severe head injury. Journal of Trauma 1993;34:216–22.

[16] Talke P, Richardson CA, Scheinin M, et al. Postoperative pharmacokinetics and sympatholytic effects of dexmedetomidine. Anesthesia & Analgesia 1997;85:1136–42.

[17] Jaeger M, Schuhmann MU, Soehle M, et al. Continuous assessment of cerebrovascular autoregulation after traumatic brain injury using brain tissue oxygen pressure reactivity. Critical Care Medicine 2006;34:1783–88.

[18] Albayrak R, Fidan F, Unlu M, et al. Extracranial carotid Doppler ultrasound evaluation of cerebral blood flow volume in COPD patients. Respiratory Medicine 2006;100:1826–33.

[19] Farag E. Dexmedetomidine in the neurointensive care unit. Discovery Medicine 2010;9:42–5.

[20] Paris A, Mantz J, Tonner PH, et al. The effects of dexmedetomidine on perinatal excitotoxic brain injury are mediated by the alpha2A-adrenoceptor subtype. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2006;102:456–61.

[21] Engelhard K, Werner C, Kaspar S, et al. Effect of the alpha2-agonist dexmedetomidine on cerebral neurotransmitter concentrations during cerebral ischemia in rats. Anesthesiology2002;96:450–7.

[22] Huang R, Chen Y, Yu AC, et al. Dexmedetomidine-induced stimulation of glutamine oxidation in astrocytes: A possible mechanism for its neuroprotective activity. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 2000;20:895–8.

[23] Sanders RD, Xu J, Shu Y, et al. Dexmedetomidine attenuates isoflurane-induced neurocognitive impairment in neonatal rats. Anesthesiology 2009;110:1077–85.

[24] Engelhard K, Werner C, Eberspacher E, et al. The effect of the alpha 2-agonist dexmedetomidine and the N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist S(?)-ketamine on the expression of apoptosis-regulating proteins after incomplete cerebral ischemia and reperfusion in rats. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2003;96:524–31.

[25] Ho SS, Chan YL, Yeung DK, et al. Blood flow volume quantification of cerebral ischemia: Comparison of three noninvasive imaging techniques of carotid and vertebral arteries. American Journal of Roentgenology 2002;178:551–6.

[26] Schebesch KM, Woertgen C, Schlaier J, et al. Doppler ultrasound measurement of blood flow volume in the extracranial internal carotid artery for evaluation of brain perfusion after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurological Research 2007;29:210–4.

[27] Gill RW. Measurement of blood flow by ultrasound: Accuracy and sources of error. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology 1985;11: 625–41.

[28] Iida H, Ohata H, Iida M, et al. Direct effects of alpha1- and alpha2-adrenergic agonists on spinal and cerebral pial vessels in dogs. Anesthesiology 1999;91:479–85.