Primary extragenital mixed malignant Mullerian tumour presenting as a painful splenic mass:A case report and review of the literature

Allan Mun Fai Kwok

Allan Mun Fai Kwok,Department of Surgery,Wollongong Hospital,Wollongong,NSW 2500,Australia

Abstract

Key words: Mixed malignant Mullerian tumour; Carcinosarcoma; Extragenital; Spleen;Metastatic; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Mixed malignant Mullerian tumours (MMMTs) are rare and highly aggressive gynaecological malignancies which feature a biphasic appearance on histological examination,consisting of both epithelial and mesenchymal tissue.First reported by Gerhardt in 1989,they most commonly arise from the uterine body but can also originate from the cervix,ovaries,Fallopian tubes and vagina (in decreasing order of frequency)[1,2].Tumours arising from extragenital sites such as the spleen and peritoneum are exceedingly rare.Other potential sites of extragenital origin include the retroperitoneum,greater omentum,colonic serosa,mediastinum and even the prostate,testes and seminal vesicles in men[3,4].MMMTs affect fewer than 2 per 100000 women per year (accounting for 2%-5% of all uterine tumours) and carry a poor longterm prognosis[1,5,6].

The usual presenting symptoms of MMMT include lower abdominal or pelvic pain and the passage of blood or necrotic tissue per vaginum[1].They are mainly encountered in post-menopausal women,with an average age of onset between 56-67 years[7,8].Risk factors include nulliparity,diabetes,obesity,prior pelvic irradiation and tamoxifen use,the last of which is associated with up to an 8-fold increased risk of developing a MMMT[1,6].Common findings include a large polypoid tumour protruding through the cervical os on speculum examination and a cystic,heterogenous,hypodense/hypoechoic mass that dilates the endometrial cavity on ultrasound and CT[9,10].At time of diagnosis,between 33%-50% of patients have evidence of lymph node or distant metastases and overall 5-year survival for all patients with MMMTs is poor at 21%[1,8,9].This reduces to only 0%-10% for those with Stage III or IV disease,with up to 90% of tumour-related deaths occurring within 18 mo[8,11].When resectable,management of these aggressive tumours includes total abdominal hysterectomy,bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and omentectomy.The role of bilateral pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy remains uncertain[7,8,12].Adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy with ifosfamide and paclitaxel is now considered the standard of care and the addition of radiotherapy has been shown to improve local control but without translating into an overall survival benefit[7,8].Negative prognostic factors include age > 70 years,positive surgical margins and Stage III-IV disease[5,12].Metastases most often occur in regional lymph nodes although transcoelomic and haematogenous spread is also possible[10].

By comparison,patients with extragenital MMMT tend to present at an earlier age and suffer a more aggressive course of disease[13].Fuet al[3]reported that there is a higher probability of relapse within 12 mo for these patients and that survival can be as short as 7 d following diagnosis.Median survival is better for those with the primary tumour arising in the pelvic peritoneum (21.5 mo) compared with those whose tumour originated elsewhere (7.6 mo for those with colonic/rectal peritoneal origin and 4.3 mo for all other sites)[14].Unfortunately,due to the scarcity of cases in the literature and the inability to conduct adequately-powered trials,the optimum management strategy for extragenital MMMT remains elusive.

We aim to raise awareness of this rare gynaecological tumour to improve its recognition in the medical community and to encourage earlier onward referral to the appropriate specialists.The importance of prompt identification and comprehensive pre-operative staging cannot be underestimated.

We describe herein the highly unusual presentation of an extragenital MMMT causing left upper quadrant pain from splenic involvement in an elderly female who presented to a general tertiary referral hospital.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

An active and independent 74-year-old woman presented to our Emergency Department with localised left upper quadrant abdominal pain.

History of present illness

The pain had been present for 1 wk and had been gradually worsening,unable to be controlled by simple analgesia.She had experienced no diarrhoea or vomiting,no recent weight loss and no other constitutional symptoms.There had been no recent injury or trauma to the region.

History of past illness

Her past medical history included a myocardial infarction eleven years earlier and long-standing hypertension,hypercholesterolaemia and type II diabetes mellitus.Previous surgery included a left total hip replacement and tubal ligation.A colonoscopy 2 years earlier had revealed two benign low-grade colonic tubular adenomas for which she was being surveilled.Regular medications included metformin 500 mg daily,hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg daily,aspirin 100 mg daily,rosuvastatin 40 mg daily and valsartan 160 mg daily.There was no known personal or family history of malignancy and she had no history of abdominal or pelvic irradiation.The patient was a lifelong non-smoker and denied any regular alcohol intake.

Family history

There was no known family history of malignancy.

Physical examination

Physical examination revealed a well-looking but overweight woman in no obvious distress (BMI 28.5 kg/m2).Vital signs were all within normal limits (blood pressure 145/76 mmHg,heart rate 71 beats/min,respiratory rate 18 breaths/min,temperature 36.4°C,oxygen saturations 97% on room air).Her abdomen was soft with left-sided tenderness on light palpation but no clinically-obvious palpable masses.

Laboratory examinations

Initial biochemical investigations revealed a mild normochromic,normocytic anaemia(haemoglobin 111 g/L; reference range 115-165 g/L) and acute kidney injury[estimated glomerular filtration rate 39 mL/min per 1.73 m2].White cell count was normal at 8.86 x 109/L,platelet count was normal at 315 x 109/L and liver function tests were unremarkable.Serum lipase was normal at 47 U/L.Internationalised normalised ratio and activated partial thromboplastin time were both normal at 1.1 and 27.8 s respectively.

Imaging examinations

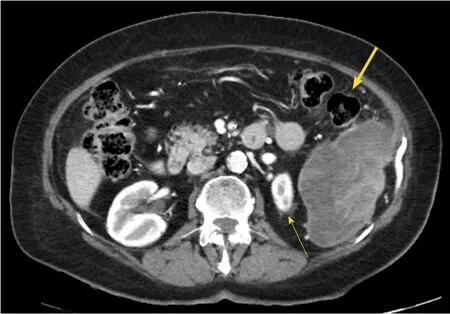

An outpatient CT scan of her abdomen and pelvis (with intravenous contrast in the portal venous phase) had been performed the day prior to hospital presentation,having already been arranged by her general practitioner.It revealed a cystic,hypodense,peripherally-enhancing heterogenous mass measuring 117 mm x 61 mm x 83 mm involving the lower pole of the spleen near the splenic flexure of the colon and causing medial displacement of her left kidney (Figure 1-2).The exact nature of the lesion was not able to be determined but was thought to be either infective or neoplastic.No other abnormalities were noted in the abdomen or pelvis.A subsequent left upper quadrant ultrasound revealed the mass to be heterogenous with internal vascularity,consistent with the earlier CT scan findings.

TREATMENT

The patient was admitted for analgesia and to expedite further investigations.Aspirin was continued throughout her admission and thromboprophylaxis was commenced with a low molecular weight heparin (enoxaparin).

Consideration was given to performing a percutaneous biopsy of the splenic mass but this was ultimately decided against due to the presence of hypervascularity.A colonoscopy was performed to exclude primary colonic pathology in the region of the splenic flexure and it revealed only uncomplicated diverticulosis.

Due to ongoing poorly-controlled pain,uncertainty of diagnosis after numerous investigations and the possibility of malignancy,an open splenectomy was performed.At operation,a left subcostal incision was made and a large exophytic cystic mass was noted to be adherent to the inferior pole of the spleen (Figure 3).There was a small volume of old blood in the left upper quadrant but no ascites or suspicious peritoneal nodules were observed.The mass was in close proximity to the tail of the pancreas but was safely dissected free of both it and the colon.Due to the position of the incision,the pelvis was not well-visualised.Post-operatively she was administered post-splenectomy vaccinations in accordance with guidelines from Spleen Australia[15].This consisted of vaccines againstStreptococcus pneumoniae,Neisseria meningitidis,Haemophilus influenzae type Bandinfluenzavirus.She was also commenced on amoxycillin 250 mg daily as lifelong prophylaxis by the consulting infectious diseases physician.

Figure 1 Coronal slice of computed tomography abdomen (with lV contrast in portal venous phase) showing a cystic,hypodense and heterogenous mass closely related to the inferior aspect of the spleen.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient's recovery was complicated by post-operative delirium for which a contrast-enhanced CT and gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)of the brain were performed.She did not develop any focal sensorimotor neurological signs or symptoms.These imaging investigations revealed acute left temporal,occipital and thalamic cerebral infarcts for which she was commenced on apixaban 5 mg twice daily by the consulting Neurologist.Aspirin was ceased following the commencement of apixaban.Carotid artery ultrasound revealed 50%-69% stenosis in the left internal carotid artery,representing the likely embolic source of her stroke.Transthoracic echocardiogram revealed only mild aortic stenosis and no evidence of mural thrombus.Within several days the patient made a full neurological recovery and her cognitive function had returned to baseline.

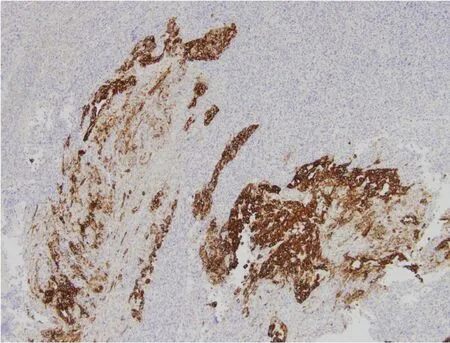

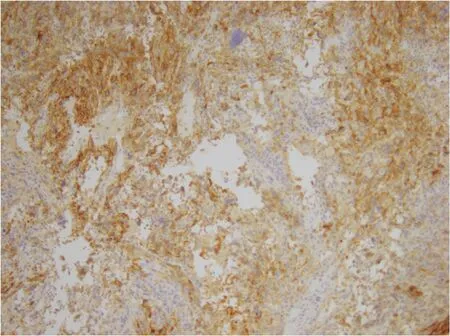

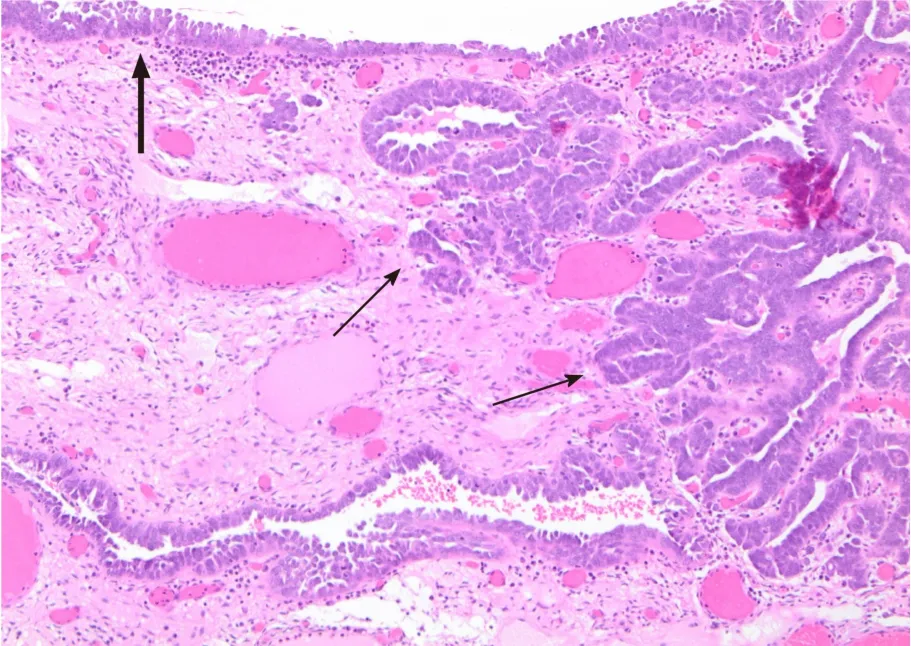

Histopathology of the splenic tumour revealed a fatty cystic mass at its lower pole with large areas of necrosis and calcification.The tumour was biphasic,containing both epithelial and sarcomatoid tissue (Figure 4).Multiple immunohistochemical stains were performed:The epithelial components stained positively for cytokeratin 7(CK7) and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) whilst the sarcomatoid components stained positively for desmin,vimentin and CD10 (Figures 5-6).The tumour was negative for p53,chromogranin,synaptophysin and CK20.The overall morphology and specific staining characteristics favoured the diagnosis of a malignant mixed Mullerian tumour with homologous differentiation.One lymph node (out of four)was found to have metastatic disease and there was evidence of microvascular invasion into the splenic parenchyma.

Given the histological characteristics of the tumour,a gynaecological origin was strongly favoured.Trans-abdominal and trans-vaginal pelvic ultrasounds were performed which showed a highly-vascular,well-circumscribed mass with mixed cystic and solid components in the Pouch of Douglas,measuring 39 mm x 36 mm x 45 mm (Figures 7-8).Neither ovary was optimally visualised.CT scan of the chest did not reveal any evidence of metastatic disease.Serum tumour markers were requested which found CA-125 to be mildly elevated at 53 kU/L (reference range 0-40 kU/L),although CA-19.9 and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels were both normal.After consulting with a gynaecologist,a fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG PET) scan was performed which revealed a 48 mm x 54 mm mass in the posterior pelvis with high FDG avidity (standardised uptake value:6.8),consistent with a malignant lesion (Figures 9-10).Speculum examination was unremarkable - the vagina and cervix appeared normal and no abnormal masses or discharge were seen.

The patient was discharged home on the 15thpost-operative day with plans to undergo an elective total abdominal hysterectomy,bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and omentectomy at a sub-specialty quaternary referral centre by an oncological gynaecologist.Unfortunately,this subsequent operation was delayed by six wk due to a combination of reasons such as deconditioning after her first surgery and the need for further cardiac and neurological investigations following her recent peri-operative stroke.No repeat abdominal or pelvic imaging was performed in the interim.At the second operation multiple malignant nodules were noted on the small bowel mesentery,sigmoid colon and greater omentum.The tumour in the Pouch of Douglas was confirmed and noted to be affixed to the pelvic floor but was not arising from the uterus.Both ovaries and Fallopian tubes were macroscopically normal.Due to a combination of reasons (widespread peritoneal dissemination with inability to achieve complete tumour clearance,recent stroke and need for post-operative anticoagulation),it was decided that embarking on extensive pelvic surgery was not clinically indicated nor in the best interests of the patient.A bilateral salpingooophorectomy and pelvic mass biopsy were performed,but the uterus and pelvic mass were leftin-situ.Intra-operative hysteroscopy revealed a normal endometrial cavity and no abnormal lesions were seen.

In the days following her second operation,the patient developed severe multiorgan failure and was referred for palliative care in keeping with her wishes and those of her family.She died on the 19thday after surgery.

Histopathological examination of the Fallopian tubes revealed multiple foci of serous intraepithelial carcinoma and one fimbrial focus of invasive,high-grade serous carcinoma (Figure 11).No sarcomatoid areas were seen and neither ovary showed any evidence of dysplasia or malignancy.The pelvic tumour biopsy contained a highgrade sarcomatous lesion with some components of poorly-differentiated adenocarcinoma consistent with the diagnosis of a MMMT and it was similar in appearance to the splenic tumour (Figure 12).

Figure 2 Axial slice of computed tomography abdomen (with lV contrast in portal venous phase)demonstrating medial displacement of the left kidney (thin arrow) due to the cystic splenic mass and its close relationship to the splenic flexure of the colon (thick arrow).

DISCUSSION

MMMTs are also known as carcinosarcomas due to their biphasic nature and can be classified according to the subtypes of epithelial and mesenchymal tissues that are present.The most common epithelial tissue subtype is endometrioid but other variants include serous,clear cell,mucinous,papillary-serous,squamous and basaloid[8,16].The sarcomatous component can be described as being homologous(containing tissue which is native to the female genital tract,such as smooth muscle or endometrial stroma) or heterologous (containing tissue which does not normally occur naturally in the female genital tract)[1].Examples of heterologous tissue include skeletal muscle (rhabdosarcoma),cartilage (chondrosarcoma),bone (osteosarcoma) or fat (liposarcoma),in decreasing order of frequency[6].Overall,there does not seem to be a difference in prognosis based on the type of sarcomatous tissue present within a MMMT although some studies suggest patients with homologous tumours fare better than those with heterologous tumours[7,8].Immunohistochemical stains are not usually required for diagnosis of an MMMT although they can be useful for identifying specific types of heterologous tissue if they are suspected of being present.Epithelial components typically stain positive for EMA and cytokeratin whilst sarcomatous tissue usually stains positive for vimentin[2,5,6,17,18],consistent with the pattern of staining in our case.

Figure 3 Macroscopic photograph of the spleen following splenectomy (measuring 105 mm x 65 mm x 45 mm).

There are three main theories that have attempted to explain the development of MMMTs:Collision,combination and conversion[12].Thecollision theorypostulates that two independent tumours (a carcinoma and a sarcoma) develop independently in close proximity to one another but remain macroscopically and histologically distinct.This theory was popularised early on but is no longer thought to be the most likely explanation for the genesis of MMMTs.Thecombination theorywas also popular for many years and suggests that a common pluripotent stem cell gives rise to a tumour consisting of two tissue types.The current prevailingconversion theoryproposes that malignant epithelial tissue undergoes a process of metaplastic de-differentiation to give rise to sarcomatous elements,a process known as epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT).This is supported by immunohistochemical evidence in embryos involving basement membrane disruption and loss of E-cadherin expression[12,18].As such,MMMTs can be considered a rare metaplastic form of endometrial carcinoma[6].While the presence of sarcomatous tissue represents regression of the tumour to a more primitive phenotype,it is actually the characteristics of the epithelial component which determine tumour behaviour,metastatic propensity and overall prognosis[19].This is reflected in the histology of metastatic MMMT lesions which almost always consist exclusively of the epithelial component[6,12,19,20].

MMMTs arising primarily in extragenital sites are extremely rare and have been explained by three possible mechanisms.In the presence of endometriosis,malignancy can theoretically arise from this ectopic tissue and may lead to development of an extragenital MMMT[20].Splenogonadal fusion is a rare congenital abnormality in which there is an abnormal connection of the spleen to the female mesonephric derivatives and as such,may be a possible mechanism for the displacement of Mullerian-derived tissue to this extragenital site[21].There have only been five previous case reports of carcinosarcomas arising primarily from the spleen:In four of these[2,21-23]the patient presented with a painful left upper quadrant mass while the fifth[24]presented with weight loss,anaemia and a painless left upper quadrant mass on physical examination and imaging.The third possibility involves the secondary Mullerian system as described by Lauchlan[25]:Unlike the primary Mullerian system (which arises from the urogenital ridge and ultimately gives rise to the uterine body,Fallopian tubes,cervix and upper vagina),the secondary Mullerian system consists of the parietal peritoneum,visceral peritoneum and underlying mesenchymal tissue that retains its potential to differentiate into gynaecological tissue.This has been proposed as an explanation for the occurrence of primary MMMTs arising from the pelvic peritoneum in the absence of uterine,adnexal,cervical or vaginal malignancy[20].

The mainstay of treatment is early and aggressive surgery but high rates of local and distant recurrence have necessitated the use of adjuvant therapies[26].Numerous chemotherapy regimens incorporating ifosfamide,paclitaxel,cisplatin and carboplatin have been trialled,without any strong evidence to indicate superiority of one combination over another.However,use of single-agent chemotherapy has been shown to lead to poorer progression-free and overall survival[26].The addition of adjuvant radiotherapy does not seem to improve overall survival but may reduce local recurrence[8].Targeted therapy using monoclonal antibodies (sorafenib and imantinib) has also been trialled but their utility remains controversial and unproven.

Directions for further research into this field include direct comparisons of different chemotherapy regimens as well as exploring the utility of radiotherapy and even targeted biological therapies.However,large trials on MMMT are difficult to conduct due to their rarity and would certainly require a multi-centre or multi-national study design in order to recruit an adequate number of patients and to achieve sufficient statistical power.

Our case is interesting for a number of reasons:Firstly,although the origin of the metastatic MMMT remains unknown findings at laparotomy and hysteroscopy excluded the uterus,cervix,vagina and ovaries,from which the vast majority of MMMTs develop.Secondly,although histological examination of the Fallopian tubes revealed numerous foci of serous intraepithelial carcinoma and one area of high-grade invasive serous carcinoma,sarcomatous tissue was absent making the diagnosis of a primary tubal MMMT less likely.Therefore,the most likely explanation is that our patient had a primary extragenital MMMT arising from either the pelvic peritoneum or the spleen which then metastasised by transcoelomic spread.Additionally,it is highly unusual for MMMT metastases to contain sarcomatous tissue components as was present in this instance.

We acknowledge that some aspects of clinical care could have been improved upon in this case.Firstly,a diagnostic laparoscopy at the first operation may have identified the presence of peritoneal nodules and pelvic pathology,despite not being detected on the initial CT scan.Even if they were identified,however,splenectomy would have still been indicated for symptomatic relief due to the persistence of poorly-controlled pain.Secondly,tumour markers were only performed after histology of the splenic mass suggested a MMMT.Performing them earlier in the clinical course may have raised suspicion of pelvic pathology sooner and expedited diagnosis of the MMMT in the Pouch of Douglas.Thirdly,there was a prolonged but unavoidable delay to the second operation due to the patient's co-morbidities.When this occurs consideration should be given to repeating the imaging studies to detect any evidence of disease progression that may preclude surgery.Such an approach may have allowed earlier identification of inoperable disseminated peritoneal disease and helped our patient avoid a futile second operation.

Figure 4 Haematoxylin and eosin (HE) stain of splenic mixed malignant Mullerian tumour demonstrating both sarcomatous (thick arrow) and epithelial (thin arrow) tissue types (magnification 200 x).

CONCLUSION

MMMTs are unusual metaplastic malignancies and those arising primarily from extragenital sites are exceptionally rare.Unlike most tumours,they undergo a process known as epithelial-mesenchymal transition which results in both epithelial and sarcomatous tissue types being present on histological examination.For this reason,they are also known as carcinosarcomas.MMMTs present at a late stage,are aggressive and are associated with a poor long-term prognosis.Management usually consists of surgery,adjuvant combination chemotherapy and possibly radiotherapy.The role of targeted biological agents has not been well established.Early recognition and referral for expedient surgery are of the utmost importance.Further research is essential in order to delineate optimal treatment strategies but such studies will be difficult to perform due to the rarity of the condition.

Figure 5 Positive cytokeratin 7 staining (dark brown) of epithelial component of mixed malignant Mullerian tumour and negative staining of sarcomatous component (magnification 100 x).

Figure 6 Positive desmin staining of sarcomatous component of splenic mixed malignant Mullerian tumour (dark brown) and negative staining of epithelial component (magnification 100 x).

Figure 7 Transvaginal ultrasound images of a well-circumscribed pelvic mass within the rectovaginal pouch with both cystic and solid components.

Figure 8 Colour doppler ultrasound demonstrating internal vascularity in the pelvic mass seen in Figure 7.

Figure 9 Axial slice of positron emission tomography-computed tomography showing high 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake by a 48 mm x 54 mm mass in the rectouterine pouch.

Figure 10 Coronal slice of positron emission tomography-computed tomography demonstrating the pelvic tumour causing mass effect on the rectosigmoid colon (arrow).

Figure 11 Section of fallopian tube demonstrating concurrent serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (thick arrow) and high-grade invasive serouscarcinoma (thin arrows) (magnification 100 x).

Figure 12 Biopsy of pelvic tumour revealing features consistent with mixed malignant Mullerian tumour (magnification 100 x).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author acknowledges the contributions of Vanita Bhargava and Reihaneh Nassirian who performed the histological assessment in this case and diagnosed the tumour.

World Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology2019年2期

World Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology2019年2期

- World Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology的其它文章

- Association of endometrioma with ovarian teratoma and mucinous cystadenoma in a patient diagnosed with endometriosis:A case report