巴塞罗那老城:城市更新还是动态提升?

胡安·布斯盖兹/Joan Busquets

尚晋,庞凌波 译/Translated by SHANG Jin, PANG Lingbo

作者单位:哈佛大学研究生院/GSD, Harvard University

译者单位:北京清华同衡规划设计研究院/THUPDI

我们可以将巴塞罗那看作一种城市传统悠久的欧洲地中海城市原型。在欧洲南部,城市大多具有特定的形式特征和历史形成过程:其城市形式的密度、紧凑性及它们通过扩张而非推倒重建的演进方式,将它们与欧洲北部的城市区分开来。其地中海的自然条件还赋予了它们温和的气候,以及与这片古老海滩的各种殖民文化之间的关联。

作为西班牙加泰罗尼亚的首府,这座城市在过去的200 年中与现代城市的发展及其工业化增长同步,实现了大规模的扩张。2019 年,巴塞罗那市有162.0943 万居民住在98.21km2的土地上,其大都市区人口约为450 万。

1 巴塞罗那,一座2000年历史城市的诞生

今天的巴塞罗那市最初的起源要追溯到公元前1 世纪,很可能在公元前15-公元前13 年之间。那时它正处于罗马统治之下。罗马人来到这里的时间则略早,与公元前218 年恩波里翁的建立属于同一时期。从那时起,这一地区的罗马化就蒸蒸日上。

巴尔奇诺殖民地就建立在早先聚居地的位置上,如同大部分加泰罗尼亚的罗马聚居地。这一时期,地处平原的很多罗马村庄以谷物生产为业。它在塔伯山系上的位置决定了它的战略地位,那是两条激流之间夹着的高差约达15m 的小海岬。激流靠近大海意味着由它们形成的盆地在某种程度上提供了一座天然海港。

巴尔奇诺殖民地的选址遵循了与大罗马帝国环地中海建立殖民地相同的标准。这宏大的殖民过程以地中海为枢纽,而海运与密集的罗马路网使之四通八达。

2 围墙之内的城市形态

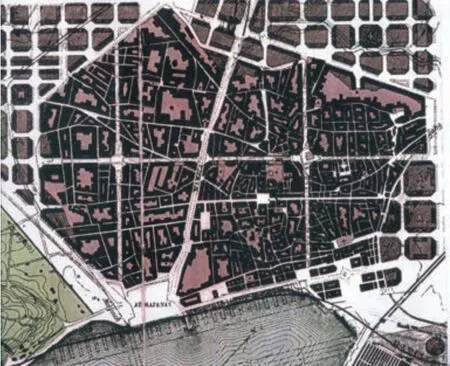

基于数十项纵横交错的工程,巴塞罗那得以建成。这些工程相互影响,彼此成就。

在明确的功能需求(防御、通行、供给、卫生等)之上,装饰和美化的需求逐渐完善并与之结合,创造出了这座复杂多变、妙趣横生的城市,人们通常称之为“老城”。为了梳理这一系列工程,特别是为了阐明营造和修补这座老城的手段,对它研究十分必要。老城几何的复杂度及其空间的丰富性,反映出的是缜密而理性的干预手段,这些手段已然超越了一般的有机论,或是当地认为老城仅是历史产物的观点所能解释的范畴。

作为对历时性解释的补充,有一种阐释方法着眼于那些构成城市形态的结构要素。这种方法或许有助于从共时性角度理解包括片段、基底与几何形态在内的巴塞罗那老城的环境特征。

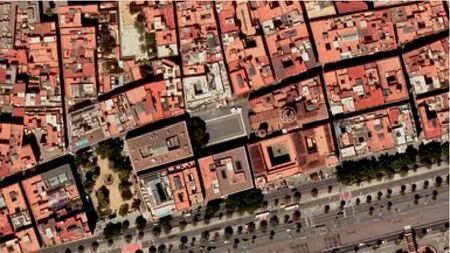

1 海滨老城被新城包围的现状/Nowadays old city near the sea and surrounded by the new city

Barcelona can be considered as the prototype of a Mediterranean European city with a long urban tradition. Cities in the south of Europe have quite specific formal characteristics and processes of historical formation: the density and compactness of their urban form and their evolution by means of extension rather than remodelling sets them apart from the European cities of the north. Furthermore, their Mediterranean nature gives them very temperate climatic conditions and has involved them in the various cultures to have colonised the shores of this historical sea.

This city has played the role of capital of Catalonia within Spain and in the last two centuries has undergone major growth, coinciding with the development of the modern city and its industrial expansion. In 2019, Barcelona city had 1,620,943 inhabitants living in 98.21 square kilometres, and its large metropolitan area had a population of around 4,5 million inhabitants.

1 The birth of Barcelona, a two thousand years old city

But the first Barcelona, the germ of today's city, dates back to the 1st century BC, possibly between the years 15 and 13, under Roman domination. The arrival of the Romans had taken place sometime before, coinciding with the founding of Emporion in 218 BC, and the Romanisation of the region was by then well under way.

The colony of Barcino stands on the site of earlier settlements, like most Catalan Roman settlements. At the same time, various Roman villages in the plain accounted for the farming of crops. Its strategic position is due to its situation on Mons Taber, a small promontory rising to an approximate height of fifteen metres, between two torrents. Their proximity to the sea meant that their basins to some extent provided a natural port.

Barcino was sited according to the same criteria as the many other colonies of the great Roman Empire established the length and breadth of the Mediterranean region, with the Mare Nostrum as the hub of this widespread colonisation, well communicated both by maritime transport and by the dense network of Roman roads.

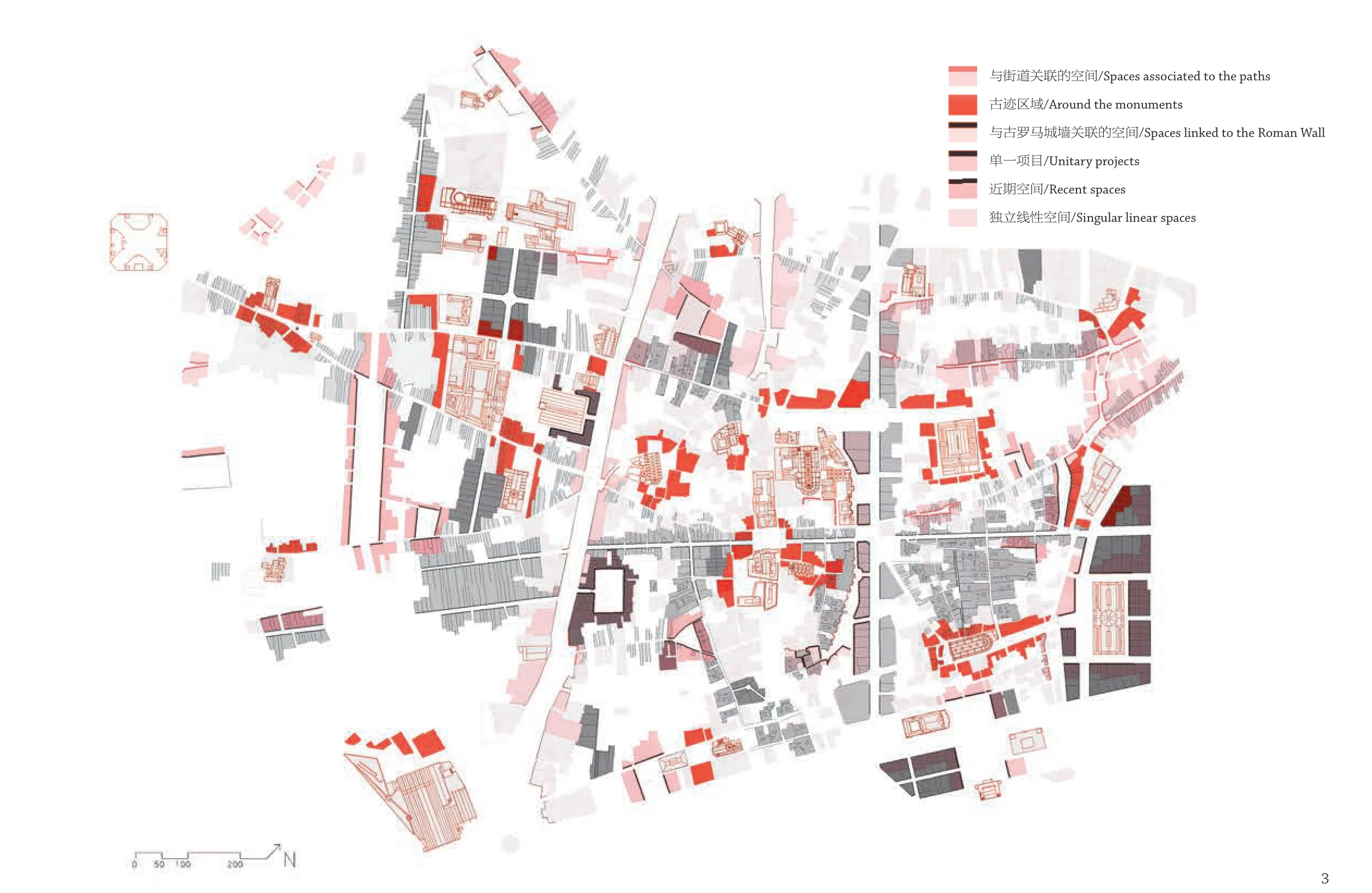

2 老城价值与形态的综合图/Synthetical map of the old city's values and morphologies

2 The urban forms inside the walled city

The city is constructed on the basis of dozens of projects, superposed and transforming and complementing each other.

Clearly defined functional requirements (defence, access, supply, hygiene, etc.) have been gradually complemented by the desire to embellish and decorate, which, combined, have produced this highly complex and interesting city that is normally referred to as the historic or medieval city, or old town. Research was needed to clarify the succession of projects and, most importantly, to interpret the instruments used to construct and modify the historic city. Its geometric complexity and spatial richness respond to considered, rational interventions that go beyond the purely organic or local views of the old town as the product of history.

To complement what is intended as a diachronic explanation, there is the interpretation of the structural elements of the urban form that may serve to explain synchronically the parts, footprints and geometries relevant to an understanding of the environmental values of Ciutat Vella.

They form three main blocks: enclosures, linear elements and functional outlines.

The enclosures are basically the enceintes that have left a real or virtual mark on the city's outline: The Roman wall, the wall built along the Rambla today reflected in streets with the name of Ronda surrounding Ciutat Vella.

The linear elements, representing communications and access to buildings, can be divided into three types: historical roads that have become urban streets; streets of housing, designed with geometric regularity to provide access to buildings; and passages, pedestrian routes connecting urban thoroughfares.

A third block includes functional spaces and covers a series of very varied categories: from monumental complexes, usually marking important city events, to the urban spaces produced by the clearing or demolition of buildings to open up the city. Finally, there is also a series of "amorphous" spaces, often produced by conflicts between new ways of organising the old town, but we will return to this subject later.

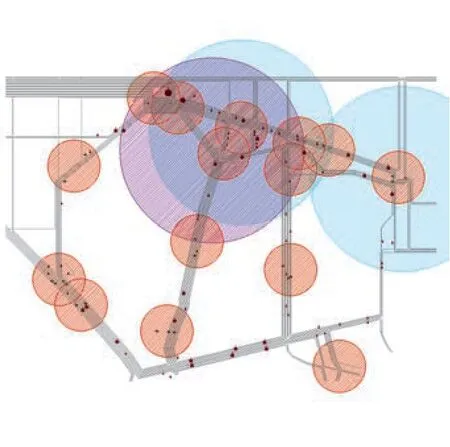

3 老城中主要干预措施的叠加图/Overlapping main interventions in the old city

这些结构要素主要可分为3 类:边界、线性元素,以及功能规划。

老城的边界是指给城市轮廓留下物理或视觉印迹的城廓:如罗马城墙,这曾沿兰布拉大街修建的围墙,如今以环绕巴塞罗那老城被称为“环路”的街道形式呈现。

线性元素代表着交通网络和建筑通路,可分为3 种类型:历史道路,如今成为了城市道路;住宅区道路,为方便出入按规则的几何形设计;以及通行步道,连接城市大道的人行路线。

第三类结构要素涵盖多种不同类型的功能空间:从纪念性建筑群——通常用以举办重要的城市活动,到开敞的城市空间——由清理拆除房屋后产生。还有一系列“不定形”空间,通常是由组织老城的新方法之间的冲突带来的,留待下文详细探讨。

3 城市更新与提升过程的对比

我们认为自19 世纪中叶以来,老城的肌理主要发生了两大变化:

(1)更新认定为消极的旧城组织。因为它们缺乏现代设施,所以就遭到了清理和更新。这样做或是出于卫生需求,或是种投机行为,从巴黎到鹿特丹,类似的案例不胜枚举。一些现代的手段——主要基于勒·柯布西耶观点的那些,当时正朝着这个方向发展。这就是“由外而起的城市改造”。

(2)考虑到历史城区提升和改善的需求,同时,试图将纪念性价值与“社会的现代需求”结合起来。

关于巴塞罗那和其他西班牙老城再生理念的发展,一定程度上要慢于欧洲中部的城市。巴黎和维也纳曾发生的老城是否应当进行“现代化”的争论及在这方面具有开拓性的成果,很晚才在我们的语境里出现。可能在这一点上,每个地方的轻重缓急是不同的,而对巴塞罗那而言,“扩展区”是当时的一大挑战。

在近几十年中,这个争论已有了长足的发展。但巴塞罗那老城所面临的一大问题仍然是战后缺乏可靠的城市再生理念与干预手段,而同一时间,其他欧洲城市的更新工作早已紧锣密鼓地开展。我们可以看到在1960-1970 年代,主要的规划工作都集中在兴建“大巴塞罗那”的都市扩张上,而巴塞罗那老城更多地同其他老城一样,维持原有城市秩序不变。这便促成了“提升过程”的发生。

4 始于老城“之外”的城市改造

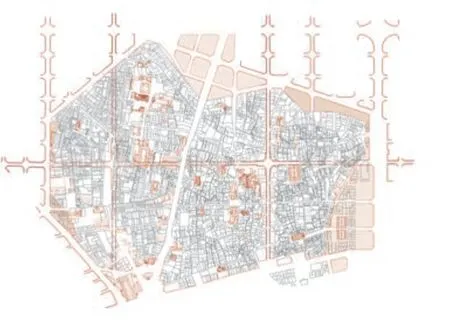

塞尔达和加里加与罗加使用了不同的规划模型来进行老城的整体改造。加里加将一种中庸的更新体系整体用于老城:依照类型对建筑进行替换和翻新,营造街道,提升纪念建筑的周边环境,并在不断扩张的“扩展区”建立一些节点。这些项目所运用的机制都在19 世纪上半叶进行过尝试,可以认为是一种“由内而起的改造”。与之相对的是,塞尔达街倡导将“扩展区”宽阔街道的新城市秩序作为合理化和重构巴塞罗那老城的机制。纪念区顺理成章地被更精细的城市“手工织补”重构,但显然,这样做需要采用一种与豪斯曼巴黎计划类似的外加的规划标准。然而,对于塞尔达,部分项目仍是以“延续与改造”的方式完成的。更令人遗憾的是,“延续与改造”的关系并未在规划中提出,而是在50年后单独实施的,因此既脱离历史情境,又因为所采取的手段与塞达尔的规划并不一致,形成了比最初方案高得多的密度。城市的清理拆除也进展缓慢,困难重重,耗时半个世纪才最终完成。

1879 年,《拜塞拉斯规划》为老城制定了一个特别行动策略,从整体布局上对大部分原有肌理进行重构。该规划在开发商的个人努力下于10 年后通过。

在市议会与西班牙殖民银行达成协议后,规划最终于1907 年全部实施。这是巴塞罗那第一个政府与私人企业合作的城市更新项目,尽管有铁路和基础设施的先例。这一协议使“干道A” 莱埃塔那大街得以建成,并按照塞尔达最初的布局将“扩展区”与港口相连。

莱埃塔那大街在巴塞罗那的城市发展过程中是至关重要的,因为它将城市的两个动态焦点连接起来:工业港口和新的住宅增长区。此外,它从老城中间穿过,提高了该区域的可达性。得益于莱埃塔那大街规划为代表的创新,巴塞罗那的新兴中心圣若梅广场延续了它的象征和功能作用:这条新街不仅提供了一条通路,还促成了新的建筑,如办公楼和商业楼的建设,为老城中心带来了真正的发展动力。这条街道的建设也使在路面下修建地铁成为可能。

3 Urban renewal versus improvement process

We assume that in the historic urban fabric there are two main process of transformation since mid-19th century:

(1) Renewal of the old urban tissues considered negative because there were built without the modern conditions; then it must be erased and renewed. This happen for hygienic or for speculative reasons and can be seen in many examples from Paris to Rotterdam. Some modern approach - mainly under Le Corbusier perspective - were moving in this direction. This will be: "Urban reform from outside".

(2) Another attitude is to consider the need of improvement and changes in the historic city but trying to merge the monumental values with the "modern needs of society".

The evolution of ideas about regeneration of the old city, both in Barcelona and the rest of Spain, has been somewhat slower than in central Europe. The application of the major debate about the "modernisation" and "maintenance" of the old town which took place in Paris and Vienna and the translation of seminal works on the subject were slow to enter our context. Here, in all likelihood, the priorities were different, as the Eixample was the great challenge for expansion of the time.

The debate has advanced a great deal in recent decades, but one of the major problems facing Ciutat Vella is still the absence of well-founded ideas and interventions in the post-war period, when European cities were working on renovation. We even see how major planning work in the sixties and seventies was concentrated on extending the city to produce Greater Barcelona, and Ciutat Vella was one part more of the existing city with regulations like those of other old towns. This constitutes the "improvement process".

4 Urban reform from the "outside" the old city

Both Cerdà and Garriga i Roca had used different planning models to address the overall reform of the old town. Garriga applied an intermediate system of renovation to the old town as a whole: substituting buildings and renovating them typologically, building streets, improving the environs of monuments and establishing singular points of connection with the growing Eixample, all project mechanisms that had been tried and tested in the first half of the 19th century, considered as "Reform from within". Conversely, Cerdà championed the new urban order of the broad streets of the Eixample as the mechanism to rationalise and restructure Ciutat Vella. The monumental areas were of course recomposed in a finer task of urban "hand stitching", but there was evidently an external planning criterion to be imposed along the lines of Haussmann's proposals in Paris. For Cerdà, however, "extension and reform" formed part of the same project. Sadly, this association was not envisaged when the Plan was passed, and it was applied separately fifty years later and, therefore, out of context and using different instruments to those devised by Cerdà, accommodating far higher densities than those suggested in his original project. The opening up or sventramento of the city also took place slowly and with great difficulties, taking half a century to complete.

In 1879, the Baixeras Plan defined a specific strategy for action in Ciutat Vella, with general layouts to restructure most of the existing fabric. The Plan was passed after ten years, thanks to the personal efforts of the developer.

The operation was finally undertaken in 1907 thanks to an agreement between the Council and Banco Hispano Colonial. This was Barcelona's first urban renovation operation involving combined public and private initiative, though the railways and utility infrastructures were a precedent. This agreement enabled the construction of Artery A, also known as Via Laietana, to join the Eixample with the port according to a layout initially proposed by Cerdà.

Via Laietana Street would be fundamental in the urban development of Barcelona, since it connected the city's two focuses of dynamism: the industrial port and an area of new residential growth. Furthermore, the fact that it ran through the middle of the old town increased this area's accessibility. The seminal heart of Barcelona-Plaça de Sant Jaume-continued to play its symbolic and functional role thanks to the innovation represented by Via Laietana: the new street not only provided access, it led to the construction of new buildings, offices and businesses that gave the old centre a real fillip. The construction of the street also meant that the Metro line could be built beneath it.

4 塞尔达的最初规划以及与当前城市地图的叠加/Cerdà' s original plan and the overlapping to the current city map

5 拜塞拉斯的最初规划与当前城市地图的叠加/Baixeras' original plan and the overlapping to the current city map

6 莱埃塔那大街从1893-1930年打开的过程/Via Laietana's opening up process along 1893 to 1930

莱埃塔那大街建设的这一案例在一定程度上解释了老城改造中所采用的不同实施逻辑。

相对于老城中其他并未被有效打开的街道而言,这个项目是成功的。干道B(同干道A 一样的垂直方向,从蒙塔内尔一直延伸到港口)和干道C (从城堡到蒙特惠奇山脚下)从未真正建成,计划中只有零星片段真正得到征收。尽管这些街道在后续的规划中得以延续(1916 年的《达德尔规划》及战后的《比拉塞卡规划》),它们从未得到行政机制或充足资金的支持。

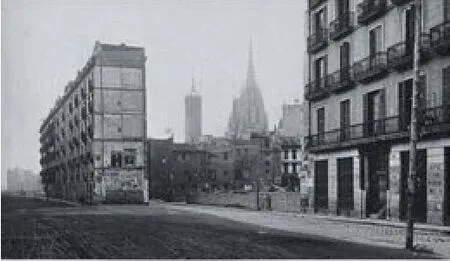

在莱埃塔那大街的这个案例中,规划显然产生了有悖常理的效果。因为为了合理化和更新这个区域,它们被“调整”了,而其布局就像是一个规划方案中的投影部分,虽然从未被实施,其所带来的影响也无法彻底被消除。这种优柔寡断被建筑的产权所有者利用,作为不修理破败老建筑的借口,导致这些区域逐步沦为名副其实的棚户。

规划的阴影与实际方案之间的灰色地带,是对衰败地区和不定形空间之所以存在的一种解释。这些空间既没有体现出恢复历史肌理的逻辑,也没有体现出基于创新理念形成的新概念。

5 1985年以来的提升过程

这个过程的规划和干预手段主要分为5 个部分,而后是一系列强调新中期“愿景”的总结性反思。

5.1 既有的规划冲突与重构策略:创建小型广场和改善原有住房

应当指出的是,巴塞罗那老城特殊的规划现状及其相对的多样性意味着有些区域仍未达到今天社会认可标准的生活条件,因而会被某些特定的社会群体占据。对此,有些指标显示,这些区域有形成贫民窟的可能,就像不久前曾发生过的那样。尽管在居住、经济或规划层面为了重新激活这些区域而付出了大量的努力,仍有很多地方需要直接或间接的行动。

干预的规模和形式可能不得不从此为之一变。像短期的大规模干预(针对开放空间、新居住肌理及文化和博物馆活动等等)这样的手段,可能会被其他更接近现有城市肌理类型的规划所取代。在对街区详细地研究后,我们发现了相当多的空置住宅。通过收购它们,我们可以妥善地进行翻新并提供给居民使用,这样就可以在尽量少地拆除具有战略意义的街块的情况下,实现在城市中心增加新公共空间的目的。

许多规划的不和谐问题都是由那些让人难以接受的建设项目带来的,一般包括在庭院中的加建或建设超高。这就需要一种新的干预逻辑,分为两个方面:

7 房屋拆除前后的梅尔塞广场,目的是营造“露天”效果,并为住房再认定创造空间/Mercé square before and after its demolition to introduce "open air" and create room for housing requalification

8 干道B最终成为拉巴尔街区的一条新兰布拉大街/Artery B finally became a new Rambla for Raval's neighbourhood

(1)以“微干预”的方式进行城市更新,这主要针对超高建设或在庭院中及屋顶上的“过度”建设。通过改善通风条件,这些住宅建筑群和街区得以重新投入使用。

The episode of the construction of Via Laietana goes some way to explaining the different logic of operation applied in the transformation of Ciutat Vella.

The relative success of this operation contrasts with the inefficiency with which other streets through the old town had been opened up. Artery B (also vertical, an extension of Muntaner down towards the port) and Artery C (from the citadel to the foot of Montjuïc) were never actually built and only small remnants of their layouts were actually expropriated. Although these streets were picked up by subsequent plans (the Darder Plan in 1916 and the Vilaseca Plan after the war) they never had the backing of administrative mechanisms or sufficient funds.

In this case, the plans had a plainly perverse effect, since they had been "justified" to rationalise and update the district, whereas their layout was like a planning designation that cast a shadow, never carried out but never entirely erased. This indecisiveness was used by the owners of the buildings in question as an excuse not to repair old structures in poor conditions, which gradually deteriorated into absolute hovels.

This grey area between the planning shadows and actual schemes was one explanation for the existence of run-down areas and amorphous spaces that responded neither to the logic of rehabilitated historical fabrics nor to a new conceptualisation on the basis of innovative ideas.

5 Improvement process since 1985

They are organised in five chapters, followed by a series of more general reflections which highlight new mid-term "visions".

5.1 The existing planning tensions and the restructuring strategy: Creating small plazas and improving the existing housing

It should be pointed out that the special planning conditions of Ciutat Vella and their relative diversity mean that some sectors still have inadequate living conditions according to today's socially accepted standards and are therefore occupied by different social groups. Here there are indicators which suggest the potential formation of ghettos, as in previous moments of recent history. Despite the major efforts which have been made to reactivate the area in residential, economic and planning terms, there are still places which seem to require direct and indirect action.

The scale and forms of intervention will probably have to be different from now on. It seems as though large-scale shock interventions (directed at open space, new residential fabric, cultural and museum activity, etc.) may be making way for another type of scheme which identifies more closely with the urban fabrics. After detailed study of the blocks we had discovered that there is quite a lot of empty dwelling. By buying them, we can refurbish properly and offer to residents to be able to demolish few strategic blocks and add new public space in the city centre.

Many of the planning tensions detected have been produced by specifically inadmissible cases of construction, generally building in courtyards and to excessive heights. This calls for a new logic of intervention on two fronts:

(1) Urban renovation by means of "microinterventions" which act on excessively built-up points or "excess" construction in courts and on rooftops, with a view to recycling these complexes of houses and streets by giving them improved ventilation.

(2) Transformations on the basis of urban spaces, seeking to stimulate the continuity of the streets, either directly or by means of small squares with subsequently improved uses, particularly for pedestrians and to air dwellings. It is proven that an improved capillary network can be coherent with

(2)基于城市空间的改造,意在直接激发街道的连续性,或直接或通过对小广场进行一系列的功能改善——特别是为人行提供便利,以及改善住宅通风。实践证明,改善后的毛细网络能够与这些场所的特色相协调。

5.2 老城遗产价值的延伸与完善

通过对建筑的在保存其纪念性价值、确定需要特别保护的对象及其周围的环境的重新分类梳理,遗产的投射主体已得到明晰。

关于城市肌理的街道、广场和特别空间形成的研究,以及对建筑序列的类型化阐释表明,巴塞罗那老城需要明确纪念性建筑或空间的观念应对他们扩展其历史价值的认识,这里的价值已扩展到它们在社会层面的象征意义而不仅停留在它们被认为或被设计为纪念物的这个事实——尽管它们被归类为“古迹或历史空间”。

这种方法要求在老城不同的区域采用不同的标准,因为不同地点的“纪念性程度”和“历史”及价值是不同的。每个部分都需要特定的评估标准,否则很难让像拉巴尔这样的区域契合其应有的遗产地位。

需要强调的是,应将遗产视为活跃、积极的要素,由此就可以将空间和建成系统阐释为同样用于经济和文化策略的地区分级政策的要素,并加以调动。

5.3 以建筑为基础的干预

对近期改造或重建项目的观察,为建筑师、管理者、施工公司、政府机构等城市改造者提供了某些工作导则,是他们能够改进干预的方法,以获得更好的整体效果。

例如,涉及设施现代化的住宅单体“修复”,与建筑或建筑群的“整体复兴”分别进行似乎是可取的,而且从巴塞罗那老城的角度,必须不惜一切代价地推广这种做法,以避免城市的衰败。这就需要立法和管理措施来确保住宅存量仍以个体所有为主,而不是走入淘汰的境地,这样城市的复兴就是一种对老城的可持续保护。

对于新建筑,必须投入大量的精力在重构和重建项目的类型化改造上。介入巴塞罗那老城的一致性,有赖于类型化的适应性改造,这涉及了建筑材料、开窗比例等方面,但并非是风格上的问题。显然在历史地段,对于创新性创作的尊重或仔细的再阐释,充分的评估是必要的。

5.4 强化老城的“核心价值”:对大型“空置容器”——不再使用的大型历史建筑——的再利用

9 叠加在老城上的规划和干预措施:住房、设施及主要公共 空间/Overlapping plans and interventions in the old city: housing, facilities and main open spaces

将大学的一部分迁到老城中心,建造一座巴塞罗那当代文化中心那样的大都市文化中心,并使它成为对市民和游客的重要吸引点,所采取的就是这个策略。沿着这一思路,我们就可以认识到很多项目的价值:波克里亚老市场的翻建及其向马萨纳艺术学校的扩建,以及建筑师恩里克·米拉莱斯设计的圣凯瑟琳市场与住宅区。

5.5 重新阐释城市结构

大都市系统的公共交通方面,老城具有高度的可达性。这是确保维护区域在功能和代表性方面“核心”价值的基础,这样的有利条件不应被破坏。因此,进一步地调节和限制私家车的通行很有必要,毕竟老城区街道规划的承载力有限,而且必须避免与遗the special characteristics of these places.

10 阿拉马达-韦尔梅街改善了老城的开放空间网络:另一 个由废弃街区的战略选择性拆除创造开放空间的例子/ Allamada-Vermell street improves the old city's open space network: another example of open space out of selective strategic demolition of derelict blocks

11 1977年和2019年的波克里亚市场和文化中心区及拉马 萨纳艺术学校/The Boqueria and Cultural Centre area in 1977 and 2019 and La Massana Art School

5.2 Extension and completion of the heritage values of Ciutat Vella

The body of reflection on heritage has been rationalised by means of work on the new catalogue in which buildings, in keeping with their monumental value, establish objects and surroundings which require particular protection.

Studies on the formation of the urban fabric streets, squares and outstanding spaces and the typological interpretation of built series suggest that in the case of Ciutat Vella, there is a need for the concept of monumental buildings or spaces to be extended to their historic value that is, their value in terms of social representation rather than due to the fact that they were conceived or designed as monuments, despite being classified as "monuments or historic spaces".

This approach must be applied to the various sectors of Ciutat Vella on the basis of different criteria, as the degree of "monumentalisation" and "history", and therefore their values, clearly varies from one place to the next. Each sector calls for specific valuation criteria: otherwise it will be difficult for sectors such as El Raval to be accorded their corresponding heritage role.

It is worth stressing the fact that heritage should be seen as an active, positive element, so that spaces and built systems can be interpreted and mobilised as elements in a reclassification policy which also applies to economic and cultural strategies.

5.3 Architecture-based intervention

The observation of recent rehabilitation or reconstruction interventions suggests certain guidelines for how urban agents like architects, managers, construction companies, government agencies, etc. can improve their interventions to produce a better overall result.

(1) For example, it seems advisable to separate the individual "rehabilitation" of a dwelling involving the modernisation of its services from the "overall rehabilitation" of a building or built complex (series of buildings) which, from the viewpoint of Ciutat Vella, has to be promoted at all costs to prevent deterioration. This case requires legal and management action to ensure that the residential stock, still predominantly marked by individual ownership, does not enter into a process of obsolescence. Rehabilitation should, then, take the form of sustainable conservation.

12 巴塞罗那当代文化中心庭院:原先的修道院如今是一个 带有开放空间的文化中心/The courtyard of the CCCB: the former convent is now a cultural center with open spaces

(2) As regards new architecture, efforts must focus on a typological reworking of restructuring and reconstruction operations. The coherence of intervention in Ciutat Vella is reliant on its typological adaptation, which should extend to the construction materials, the proportion of openings, etc., rather than being a question of style. It is evident that on historic sites, respect for or a careful reinterpretation of seminal compositions has to be duly evaluated.

5.4 Reinforcing the "central value" of the old town by recycling large "empty containers" - large historical building without use any more

This was the strategy to bring part of the University to the centre and to create a metropolitan cultural centre like CCCB, becoming a major attraction for citizens and tourists.

In the same line, we can acknowledge the refurbishing of old markets as Boqueria and his extension towards Massana Arts School and Santa Caterina market and housing sector developed by architect Enric Miralles.

5.5 Reinterpreting the urban structure

The high degree of accessibility of Ciutat Vella with regard to the metropolitan system by means of public transport. This is a favourable condition which should not be undermined, as it is one of the bases for ensuring the maintenance of the district's "central" value in functional and representative terms. For this very reason, private car access needs further modulation and restriction, as the capacity of the area's street layout is limited and conflict with heritage values must be prevented.

Furthermore, it is necessary to "clarify" the use of streets for activities which support the most scattered fabrics (residence, shops and services).Conversely, the general urban structure still offers opportunities which are very important to a better organisation of spaces devoted to residents and visitors.

6 Long-term strategy

Another important issue is perhaps Ciutat Vella's forms of relation with the rest of the metropolitan area. It is true that the attraction that some parts of the city hold for others lies in their intrinsic qualities, but above all in their accessibility. This includes systems of access using public transport but also private mobility, which is much more restricted than in other city areas which grew up alongside mechanical forms of mobility. A new understanding of the present-day situation in the light of restricted access, parking and public transport policies could contribute to an explanation of the qualities of Ciutat Vella with regard to the rest of the system.

Particular care is also needed to understand its relations with adjacent districts, principally the Eixample and Poble Sec, by means of the use of lateral spaces such as the Rondes (Ring Road), 产价值形成冲突。

13 此外,需要新的住宅项目来填补住房的缺口/Also, new housing projects were needed to fill the gap of housing shortage

14 公交车线路、地铁站和火车站赋予了老城中心性,并实 现了纪念性空间的步行化/Bus lines, subway stations and railway station brings centrality to the old city and allows the peatonalisation of monumental spaces

此外,有必要“明确”街道在支撑大部分稀疏的肌理(住宅、店铺和设施)运作中所起到的作用。相对的,整体城市结构仍有多重机遇,对于更好地组织服务居民和有空的空间十分重要。

6 长期策略

另一个重要问题可能就是老城与大都市区其他部分的关系的形式。无疑,城市某些部分对其他地方构成吸引力的是它们的内在品质,而首要的就是可达性,这包括了公共交通系统的可达性及私家车的移动性,不过比起其他按照移动性的机械形式生长出来的城区,老城对后者的限制要多得多。从限行、限停车和公共交通政策的角度重新理解当前的状况,有助于解释老城相对于巴塞罗那市系统其余部分的特质。

还需要特别注意的是,要通过在老城墙遗址上的“环路”这种侧向空间区,理解它与扩展区和Poble Sec 等邻近市区的关系。这种思考意在重新考虑老城中“切向”或内部干道要素的作用,比如莱埃塔那大街、哥伦布大道和“环路”。

与维也纳和汉堡等其他欧洲城市不同,巴塞罗那标明老城城廓界线的历史“环路”从未能给老城墙与新城提供相互关联的良好空间。不过这个局面如今仍有可能被扭转。

关于干预的可能性,以下3 点尚可讨论:

(1)从实现更大程度整合的角度对城市规划和遗产空间的干预;

(2)以各分区的总体复兴为目标的公共干预与多方干预。这些分区均已彻底更新,因此可以与公共空间的干预进行联动;

(3)为实现文化、旅游、社区复兴等的策略,可为规划的介入提供互补性空间。

为了尝试理解老城在巴塞罗那总体城市系统中的潜在作用,这将带来对其全面的评估。把多种“愿景”或“策略”当作讨论的基本要素而不是提出最佳选择,以此发掘老城的巨大潜力。

巴塞罗那老城与其他欧洲的历史城市之间的比较,也能够揭示某些中期策略所能带来的可能性。

经过努力将巴塞罗那老城的核心角色重新定位为文化、教育和博物馆中心,如今或许是一个提倡历史旅游线路的最佳时机,这将提升老城遗产的一致性。对 “博物馆-城”的概念尚有考虑的空间,这可使城市更趋向于“艺术城市”的方向发展,并以此避免负面的专门化。

类似地,一种形式更为紧凑的复兴,能够借由讨论一种假设,建立将老城作为一系列“住宅街道”和“住宅邻里”,以及作为一座具有其独特性的“住宅城市”的认识。

还可以重新激活“典型城市”理念,并在罗马式城市中心划定各种空间,通过环形休闲步道优化纪念性空间的大规模旅游开发,以减少负面影响,并助力其他游线。

这样我们就可以根据历史上或当今的用途来谈论“城市及其历史空间”——无论是绿色空间还是建成空间,这将证明这些空间引发或传播重要活动的能力,以及联系那些遍布城市肌理中的小规模第三产要素。这会突出地体现在某些最重要的公共空间中。

这些“方向”能够调动和催化出各种行动,对空间和建筑进行评估,并从城市中为其找出对今天具有实用价值和代表性的内容。曾在城墙的庇护下生长和转型的巴塞罗那老城,发展成为了今天活力四射、魅力无穷的大型中心。

在这样的情况下,对老城的干预产生了一种新的方法。这种方法基于对具代表性的关注,从而产生对现实的其他阐释。这些阐释或许会让我们更接近一个这样的愿景:城市的历史是基于个体世界的新建筑形式的产生与基于集体世界的新城市空间的产生之间持续的辩证的结果。这种创造性的关系在老城中有着生动的体现,而且这种创造性的关系应当继续维持,为老城的复兴提供语境。在这一过程中,一种双重特性亟待关注:充满本地历史特色的大都市空间,这种赋予它特有价值的组合。□on the site of the old town wall. This reflection is intended to reconsider the role of the "tangential" or internal arterial elements in Ciutat Vella, such as Via Laietana, Passeig Colom and the Rondes.

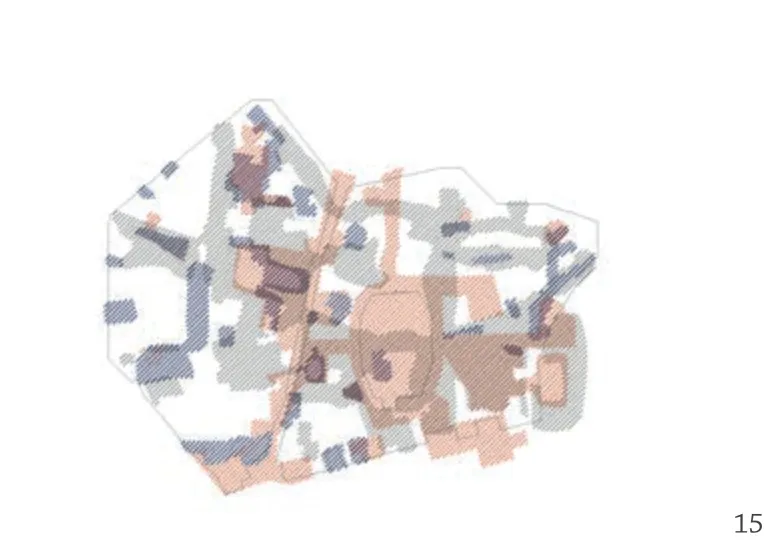

15 老城的新专题视图:休闲与文化城市、商业城市、艺术 城市/New thematic views for the old city: the city of leisure and culture, commerce, and art

Unlike other European cases such as Vienna and Hamburg, the historic rondes of Barcelona, marking the boundary of the old enceinte, have never provided a good space of interrelation between the old town walls and the new city. It may still be possible to set this situation to rights.

As regards possibilities for intervention, there are few areas to debate:

(1) Intervention in urban planning and heritage spaces with a view to achieving greater integration;

(2) Public and mixed interventions aimed at the overall rehabilitation of sectors which have been definitively brought up to date and can therefore be linked to interventions in public spaces, etc.

(3) Sectorial strategies for culture, tourism, social rehabilitation, etc., which may produce complementary spaces for planning intervention.

This would lead to a global evaluation of the old walled town in an attempt to understand its potential roles in Barcelona's overall urban system.Various "visions" or "strategies" are formulated as general elements for discussion with a view to highlighting Ciutat Vella's vast potential, rather than prioritising any one of them as being the best.

A comparison of the old town of Barcelona with other historic centres in Europe reveals the possibility of certain mid-term strategies.

After efforts to reinstate culture, education and museums to a central role in Ciutat Vella, this might be a good moment to suggest historic itineraries which would increase its coherence in terms of heritage. There is room for reflection on the concept of the "museum-city" to direct it more towards a "city of art" and therefore avoid negative specialisation.

Similarly, a more compact form of rehabilitation could help to produce an understanding of Ciutat Vella as a series of "streets of houses" and "neighbourhoods of houses" a "city of houses" with specificities of its own, by way of a hypothesis for discussion.

The idea of the "representative city" could also be reactivated, with its assigned spaces at the heart of the Roman city, and leisure and walking circuits to rationalise the mass tourist use of its monumental spaces, in an attempt to reduce negative impact and support other itineraries.

We could then speak of the "city and its historic spaces", be they green or built, according to their historic or present-day use, which demonstrate their capacity to induce or disseminate central activities and consolidate the small-scale tertiary elements scattered throughout its fabric, which could best be expressed in some foremost public spaces.

These "directions" could mobilise and catalyse various initiatives which would evaluate and find present-day, practical and symbolic contents for the spaces and buildings within the city which grew and transformed inside the town walls, and which has developed into the large centre of today that is so full of life and charm.

And against this backdrop, interventions can bring to bear a new approach based on a concern with representation which produces other interpretations of reality. They will perhaps bring us closer to a vision of the history of the city as an ongoing dialectic result of the invention of new forms of architecture, based in the individual world, and the invention of new urban spaces, based in the collective world. It is this creative tension which is so vitally expressed in Ciutat Vella and which should continue to provide the context for its recuperation. This process calls for attention to a dual condition: a metropolitan space full of the local conditions of its history, a combination which gives it its particular interest.□

16 翻修后的圣凯瑟琳菜市场,其混合功能包括了养老住房/ The refurbished food market of Santa Caterina with has a mix-use program to include housing for the elderly