Effectiveness of integrated nursing interventions for fatigue in patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials

Xio-Lin Zuo, Yn Wen, Shng-Qun Gong, Fn-Jie Meng,

aDepartment of Nursing, The Central Hospital of Luohe (the First Aff i liated Hospital of Luohe Medical College), Luohe, Henan 462000, China

bTianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Tianjin 300193, China

Abstract: Objective: To evaluate the effectiveness of integrated nursing interventions for fatigue in patients with advanced cancer.Methods: Medline, Pubmed, Embase, CINAHL, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library were searched systematically till June 2017.A systematic review was conducted to collect randomized controlled trials (RCTs) reporting on the effect of nurse-driven interventions to improve fatigue in patients with advanced cancer. Quality assessment was conducted using the Cochrane Collaboration's risk of bias tool.Results: Six RCTs involving 736 adult participants were included. The fatigue intensity was improved signif i cantly by nursing interventions. The analyzed results revealed signif i cant improvements in the intervention group: less than 3 months (standard mean difference [SMD] = -0.33, 95% conf i dence interval [CI] [-0.48, -0.19], P < 0.01) and more than or equal to 3 months(SMD = -0.40, 95% CI [-0.57, -0.24], P < 0.01). Four studies with a moderate risk of bias were judged, and the remaining studies were at high risk of bias.Conclusions: The results indicate that integrated nursing interventions may relieve fatigue in patients with advanced cancer. However,due to the high risk of bias in most of the included studies and the diversity of interventions, the results and implementation process should be carefully monitored.

Keywords: fatigue · neoplasms · nurses · palliative care · advanced · evidence-based nursing · systematic review · hospice and palliative care nursing

1. Introduction

Fatigue is associated with a high prevalence of multicausal symptom in patients with terminal cancer, which is classically def i ned as a distressing, persistent, subjective sense of tiredness or exhaustion related to cancer.1Cancer-related fatigue can decrease patients' activity level resulting in the loss of muscle mass and reduced cardiac output, which can leave patients in a deconditioned state.2Moreover, fatigue can lead to negative emotions and spiritual distress, sleep disturbances, and treatment noncompliance for both patients with cancer and their family members.3

Pharmacotherapy is rarely adequate, and the safe and effective interventions against fatigue in these patients are needed. Recently, a growing number of investigators have been chosen to develop interventions delivered by nurses to address fatigue, which have been shown to be promising. These nursing interventions have advantages in relieving fatigue for both short- and long-term periods. Although these studies illuminate the evidence in their respective areas, to our knowledge, no integrated reviews have been carried out so far.

2. Methods

2.1. Inclusion criteria

The searching format was applied to address the research question and establish eligibility criteria. The diagnosis of fatigue in patients with cancer includes the following:(1) self-reported fatigue: patients report fatigue as a state of physical disturbance and loss of function, with exhaustion being the lead factor in reduced physical activity;4(2) diagnosed by questionnaires: brief assessment tools such as the Numeric Rating Scale of fatigue and the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale of fatigue.

2.2. Search methods

Studies were identif i ed by searching Medline, Pubmed,Embase, CINAHL, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library from the inception of databases to June 2017.We used MeSH terms and all fi elds when searching. The search strategy was as follows: (“Neoplasms” [MeSH] or“Carcinoma” [MeSH] or “cancer” or “oncology” or “malignant”) and (“advanced” OR “incurable” OR “metastasized” OR “terminal” OR “late stage”) and (“Nurses”[MeSH] or“nurse*” or “nurs*” or “care”) and (“Fatigue”[Mesh] OR “Mental fatigue” [Mesh]) and (“randomized controlled trial” or “random allocation” or “double-blind method” or “single-blind method”).

2.3. Study selection

One reviewer screened the study on the basis of title and abstract. If any doubtable information existed, the articles were included in the full-text screening phase.The full texts of candidate articles were screened by two independent reviewers. Any disagreement was discussed with additional reviewer. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) participants: adults with advanced cancer aged 18 years or older; patients with recurrent cancer and who were undergoing chemotherapy or undergoing radiotherapy were also included; (2) intervention: nonpharmacological interventions driven by nurses aimed at managing fatigue due to cancer or cancer treatment;(3) comparator: any comparator; (4) outcomes: fatigue measured by authorized measurements; (5) study design: randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published in English in a peer-reviewed journal. We excluded quasi-RCT studies, studies without full texts, and duplicates.

2.4. Quality assessment

The quality assessment of the selected studies was conducted independently using the Cochrane Collaboration's tool. Any disagreement between reviewers was resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer.

The quality items checked were the following:sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding,incomplete data outcomes, selective outcome reporting,and other biases, in which each of the components can be rated as low, unclear, or high risk of bias.

2.5. Data collection process and synthesis

Data extraction was performed independently by two authors. As a result, the details of the extracted data were as follows: the fi rst author's name and publication year; detailed characteristics of interventions; participants (country and setting, diagnose, sample size,age, and gender); and outcome measures, follow-up,and main results. Continuous outcomes were compared using standard mean differences (SMDs) and a 95%conf i dence interval (CI) with a fi xed-effect model. If statistical pooling was not appropriate, fi ndings were collected in tables and described narratively.

3. Results

3.1. Study selection

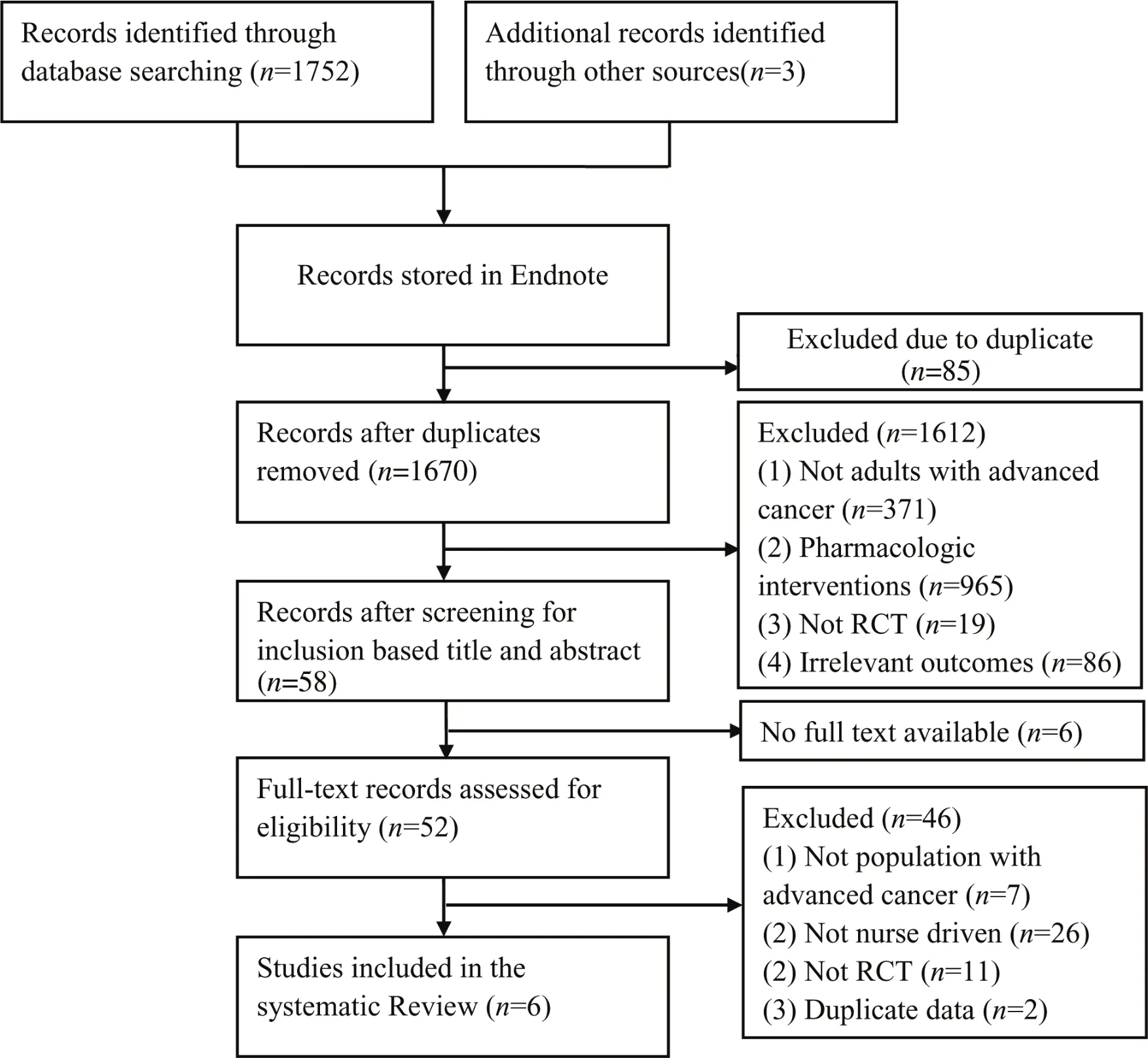

The fl owchart of the selection of eligible studies is shown in Figure 1.

The initial search yielded 1752 original articles.Three additional articles were identif i ed after checking the reference lists which resulted in a total of 1755 articles. After the removal of duplicates, 1670 studies were screened for inclusion based on titles and abstracts.Of these, the full text of the remaining 52 studies was assessed. It was found that seven were not related to patients with advanced cancer, 26 did not focus on nursing interventions, eleven were non-RCTs, and two had duplicate data. We e-mailed the corresponding author to ask for the available outcome data, and six studies were included in the review eventually.5-10

3.2. Outcome analyses

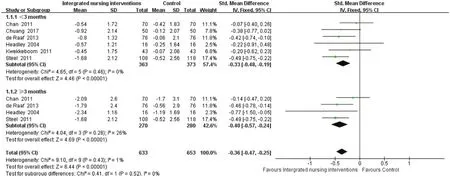

All patients in the studies were already experiencing fatigue at baseline, and different tools were used in the studies to measure fatigue including the following: patientreported measures: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Fatigue (FACT-F) scale, Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI), Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI),and the revised Piper Fatigue Scale; clinician-assessed measures: muscular strength. The analyzed results revealed signif i cant improvements in the intervention group: less than 3 months (SMD=-0.33, 95% CI (-0.48,-0.19), P<0.01) and more than or equal to 3 months(SMD =-0.40, 95% CI (-0.57, -0.24), P<0.01; Figure 2).In addition, signif i cant improvements in muscular strength were seen in favor of the intervention group.

Figure 1. PRISMA fl owchart of selection process.

3.3. Quality appraisal

The risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration tool, and it is shown in Figure 3.

In two studies,5,6the allocation sequence was adequately generated and concealed by drawing lots from opaque envelopes or sealed boxes. The method of concealment of allocation was not fully reported in the remaining studies; therefore, the risk of bias was unclear. All trials had adequate random generation by fl ipping a coin or computer-generated schedule. Only one trial7reported blinding of participants. Three of the trials reported assessor blinding.6-8With a loss to follow up ranging between 0% and 35%, attrition was problematic in the majority of the studies. Two studies6,8reported missing outcome data which balanced in numbers between the intervention group and control group.The remaining did not mention the reason for missing data and did not carry out intention-to-treat analysis,which led to attrition bias. Patients did not complete the study mainly due to disease progression or death. All six studies adequately reported the results (fatigue scores as primary outcome). Considering other biases, all trials had adequately matched participants in the two groups and were free from baseline imbalance bias. For early stopping, none of the six trials were stopped in advance.The source of funding bias was unclear in the trials by Chan et al.10and Headley et al.8The sources of funding in other studies were academic medical or social science foundations, and we considered the trials to be free from risk of source of funding bias.

All studies had at least two risks of bias. The four trials5-8received overall moderate risk of bias, and the others received high risk of bias.

Figure 2. Forest plots of pooled results for integrated nursing interventions on fatigue in patients with advanced cancer.

Figure 3. Summary risk of bias.

3.4. Study characteristics

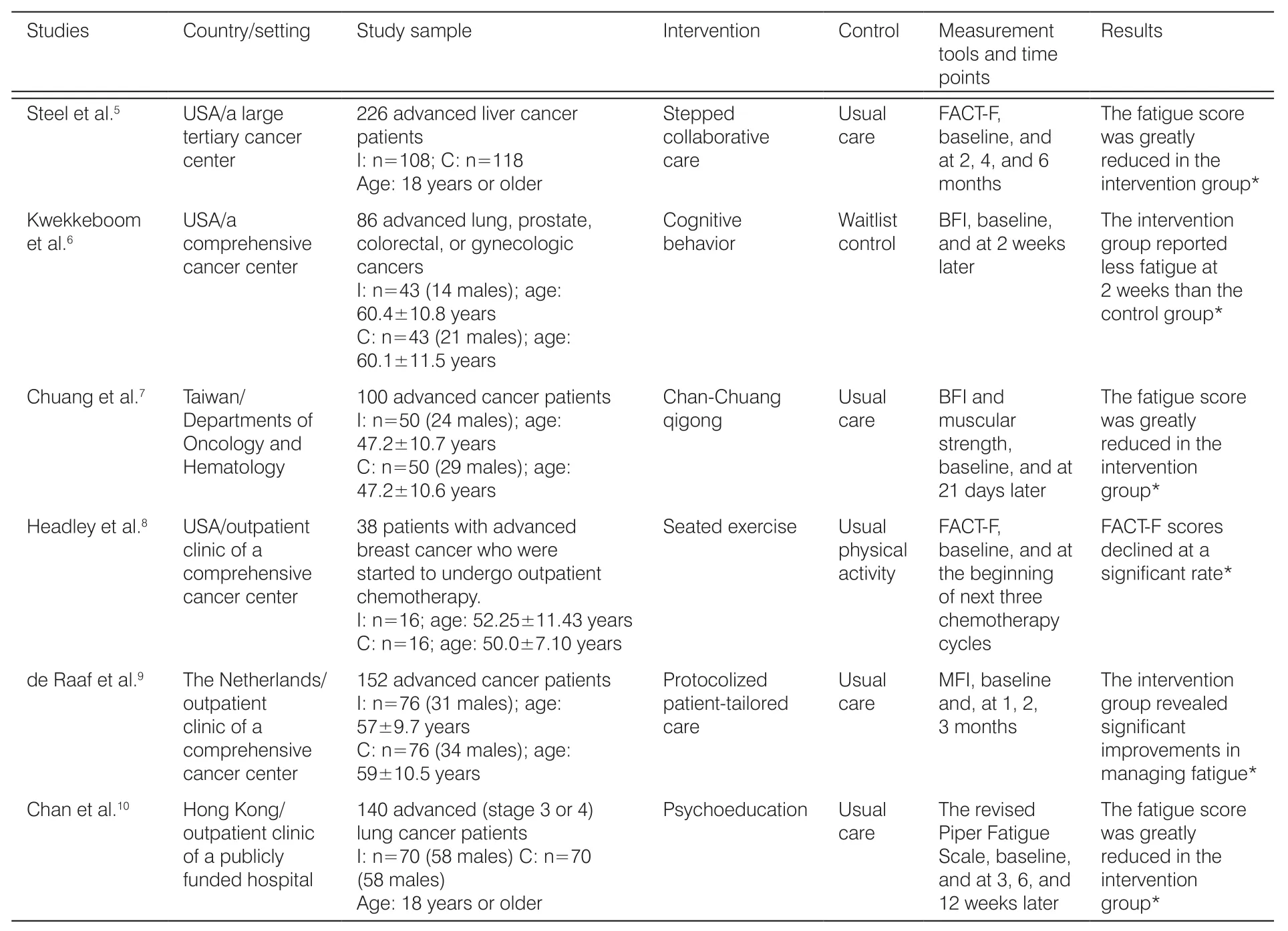

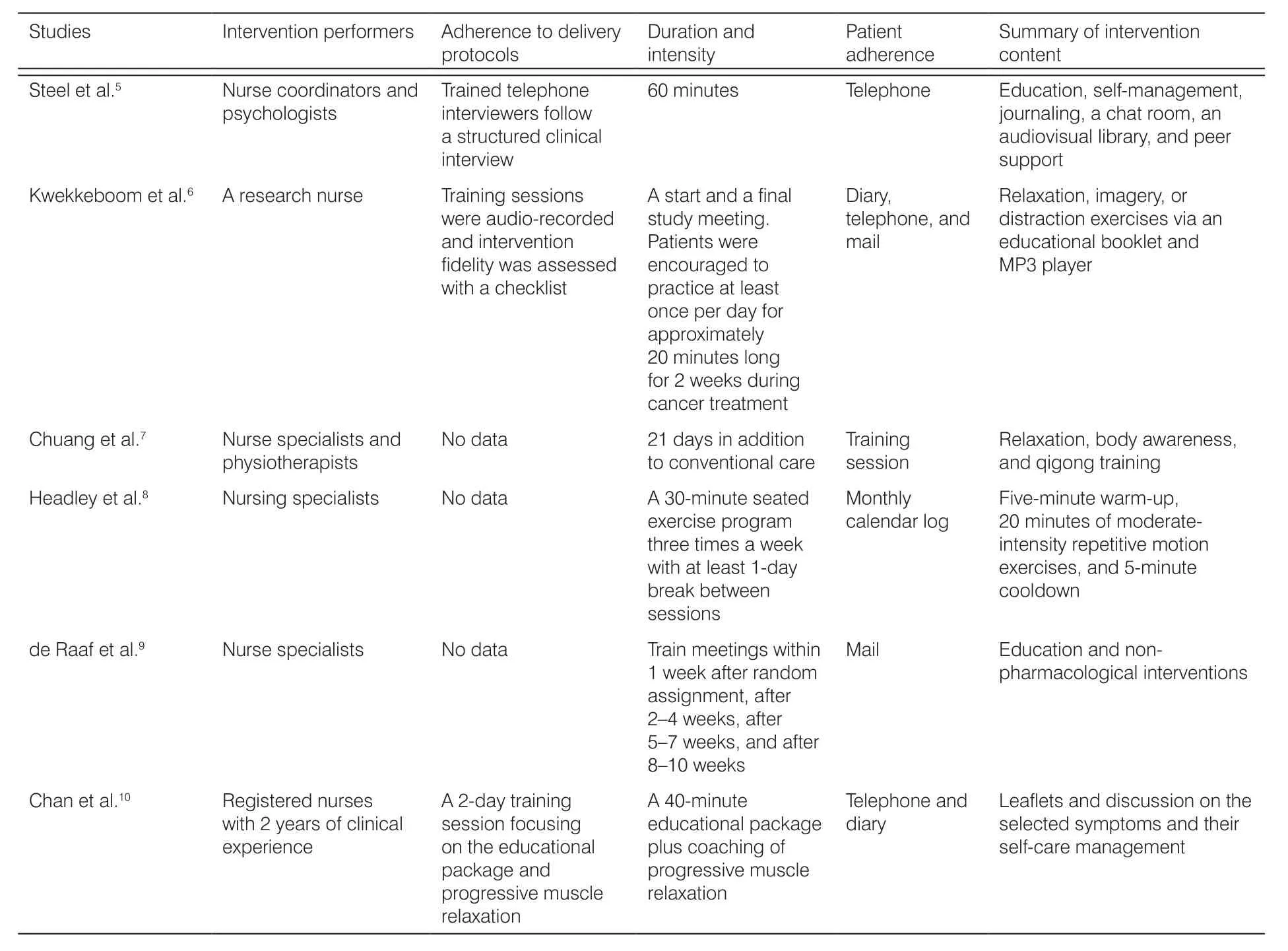

The characteristics of these studies are summarized in Table 1. The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 2.

Total sample size in terms of the number of patients was given in all of the studies and ranged from 38 to 226, and the pooled sample size was 736 (intervention group = 363, control group = 373). The included studies were conducted in the USA, the Netherlands,Hong Kong, and Taiwan. The publication year range of the included studies spreads over a considerable period from 2004 to 2017.

The nurse interventions in the six studies were varied, including stepped collaborative care intervention, protocolized patient-tailored care, psychoeducation, seated exercise, cognitive behavior, and qigong program. The studies did not compare any treatment or usual care. Usual care in the trials included routine medical care from the nurse and attending physician.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study instruments and samples.

Except the studies such as Chuang et al.,7Headley et al.,8and de Raaf et al.,9the remaining studies were all conducted based on protocols. Only Chan et al.10provided full access protocol online. For the intervention, the session of intervention varied between 20 and 60 minutes each time. The studies correspondingly had the least and most number of interventions of 4 and 40 sessions, respectively. Contacts between patient and nurse were face to face, telephone, or mixed.

Interventions were delivered by clinical nurses,research nurses, and nurse coordinators, and all nurses followed a training session. Nurse-coordinated interventions were conducted in the studies by Steel et al.5and Chuang et al.,7one with psychologists and the other with physiotherapists. Regarding the delivery form,interventions were conducted individually, in groups, or combination of both.

3.5. Adverse event in nurse practicing

None of the researchers reported any adverse effects due to the interventions.

4. Discussion

Six studies met the inclusion criteria. The varied nursing interventions were categorized into stepped collaborative care, protocolized patient-tailored care, psychoeducation, seated exercise, cognitive behavior, and qigong program. The meta-analysis results showed signif i cant improvement in fatigue with nurse-driven interventions,while due to a small number of studies the results and implementation process should be carefully monitored.

Effective management of fatigue requires comprehensive interdisciplinary care.11As Steel et al.5advised,the collaborative care team included nurses coordinators, physicians, psychologists, and most importantly,patients and their caregivers, all worked together as a team. The team was formed to monitor patients during treatment and to assess as well as treat symptoms via online. Nurse coordinators played a key role to monitor fatigue level by phone calls. Tele-monitoring, such as Web-based interventions, has been recommended to patients with advanced cancer who may not have access to traditional face-to-face treatments and reduce health care cost.5,12Similarly, a study used palliative consultation team, where registered nurses were working as practitioner and counselor in fatigue management.13The above two studies revealed signif i cant reduction in fatigue distress in patients with advanced cancer. Nurses employed to do screening, assessment, education, and follow-up adherence in the team and discuss the fi ndings with the specif i c team members.14The team care should follow a standardized management manual or protocol.15

Table 2. Characteristics of interventions.

The negative effects of bed rest are well known which possibly induce a vicious cycle between inactivity and intensif i ed fatigue.16,17Thus, recent research suggested a balance between activity and rest that could reduce fatigue particularly in the late stage of cancer.18Thus,nurses must be well trained and tailored to addressing populations' exercise tolerance and potential effects on fatigue management.19Chuang et al.7used the qigong program including body awareness training, relaxation,and massage for patients undergoing chemotherapy,which showed broad effects on fatigue and muscular strength. Similarly, Headley et al.8advised that terminal cancer survivors may much benef i t from exercising in a chair in the safety and comfort home setting. Depression was signif i cantly related to fatigue in several studies.7,8

Chan et al.10also used psychoeducation for cluster symptoms (fatigue, anxiety, and breathlessness) in advanced lung cancer, which proved a promising results;however, the attrition was problematic in this study.Thus, duplication in intervention should be carefully monitored. Kwekkeboom et al.6proved that relaxation,imagery, and distraction are very useful components in cognitive behaviors; those practices could build peaceful or comfortable experiences for listeners and are used them to treat fatigue effectively.6Overall, nurses with standard training in cognitive intervention could help patients alleviate symptom distress and improve a lot of symptoms particularly fatigue.20-22

We recommend that effective and feasible interventions to improve fatigue in patients with late-stage cancer should be practiced in addition to fi ve criteria:(1) practicing tailored to the patient. Nurses should build individualized programs according to the patient(such as current level of energy, tolerance, psychological functions, preferences, expectations, and motivation)and the advanced cancer (treatments and remaining lifetime);5,9,17(2) long-term intervention. The effects of fatigue alleviation would be transient unless the intervention is continued, especially cognitive behavior.6Thus, patients should continue using the skills to manage fatigue although the intervention is done.23de Raaf et al.9also argued that these eligible interventions should be part of the routine treatment of fatigue. (3) Optimizing patient adherence: the dropout rates were relatively high among the included researches. Steel et al.5proved that patients who did not complete the study were signif icantly more likely to report higher fatigue severity. In the included studies, the usual formats of follow up included diary, telephone, e-mail, and log. Particularly, telephone call was perceived by patients with advanced cancer as helpful for symptom management, assessment of negative effects, and promotion of self-management.24Headley et al.8reported that patients and caregivers welcome nursing telephone as a way to maintain contact with nurses, where patients may feel they are receiving care and have a positive effect on outcomes eventually;(4) caregiver involvement. de Raaf et al.9suggested that allowing caregivers to receive interventions may help improve outcomes. Because patients with advanced cancer usually need caregiver's assistance, caregiver can assist patients and promptly remind them when they experience fatigue.11(5) Ensuring the safety: although none of the researchers in the six trials reported any adverse effects caused by nurse-driven programs,patients with advanced cancer reported many uncertain factors; for several skilled interventions such as cognitive behavior and exercise, nurses should be well trained or practiced under the professional supervision.25,26Chuang et al.7also advised to increase the need for daily pre-exercise screening and training sphygmomanometer to ensure safety. Overall, feasible screening, tailored practicing, professional skill, and close monitoring are essential factors to prevent serious adverse events during intervention.27

Several limitations of this study require caution in interpreting the results. First, although the authors tried to include many articles, non-English and unpublished studies were excluded from the review, which might present a selection bias. Second, the sample size in each research was small. Third, the quality of some studies was relatively low, especially, the attrition rates were high in several studies. Finally, the outcomes of fatigue were measured mainly by patient-reported scales.A survey revealed that patients with advanced cancer were not receiving the help they need.12Thus, better symptom identif i cation and management are warranted for these patients, especially, the optimal method or frequency of screening and practicing for fatigue is essential. Cost-effectiveness is another important outcome to address in the future trials. The included interventions could be considered as a part of standard care in the future trials. Finally, future studies should have a higher methodological quality.

5. Conclusions

Integrated nursing interventions in this systematic review included stepped collaborative care, protocolized patient-tailored care, psychoeducation, seated exercise, cognitive behavior, and qigong program. However, because of the overall low quality of the included studies, the results and replication of the interventions need to be taken care. Despite limitations, these fi ndings suggest that the interventions could be complementary approaches for improving fatigue in these patients, with varying potential clinical signif i cance. We also concluded that there are fi ve criteria along with interventions to improve fatigue in patients with terminal cancer. More well-conducted RCTs with lager sample sizes are needed.

Ethics approval

Not declared.

Conf l icts of interest

All contributing authors declare no conf l icts of interest.

- Frontiers of Nursing的其它文章

- Inf l uence of physical self and mindfulness on the academic possible selves of freshman nursing students

- Research status and hotspots of economic evaluation in nursing by co-word clustering analysis

- Analysis of the application and practice of PDCA cycle in management of the naked medicine dispensing—the quality and safety of the drug

- The effect of empowerment education on depression level and laboratory indicators of patients treated with hemodialysis: a meta-analysis

- Investigation and analysis of attitudes and knowledge of aging among students in different majors

- The eligibility criteria, training content, and scope of practice for prescriptive authority for midwives: a modif i ed Delphi study†