Heat dissipating upper body compression garment:Thermoregulatory,cardiovascular,and perceptual responses

Iker Leoz-Aurre*,Nichols Tm,Roerto Agudo-Jim′enez

a Department of Health Sciences,Public University of Navarre,Navarre 31500,Spain

b UCT/MRC Research Unit for Exercise Science and Sports Medicine,Department of Human Biology,University of Cape Town,Cape Town 7725,South Africa

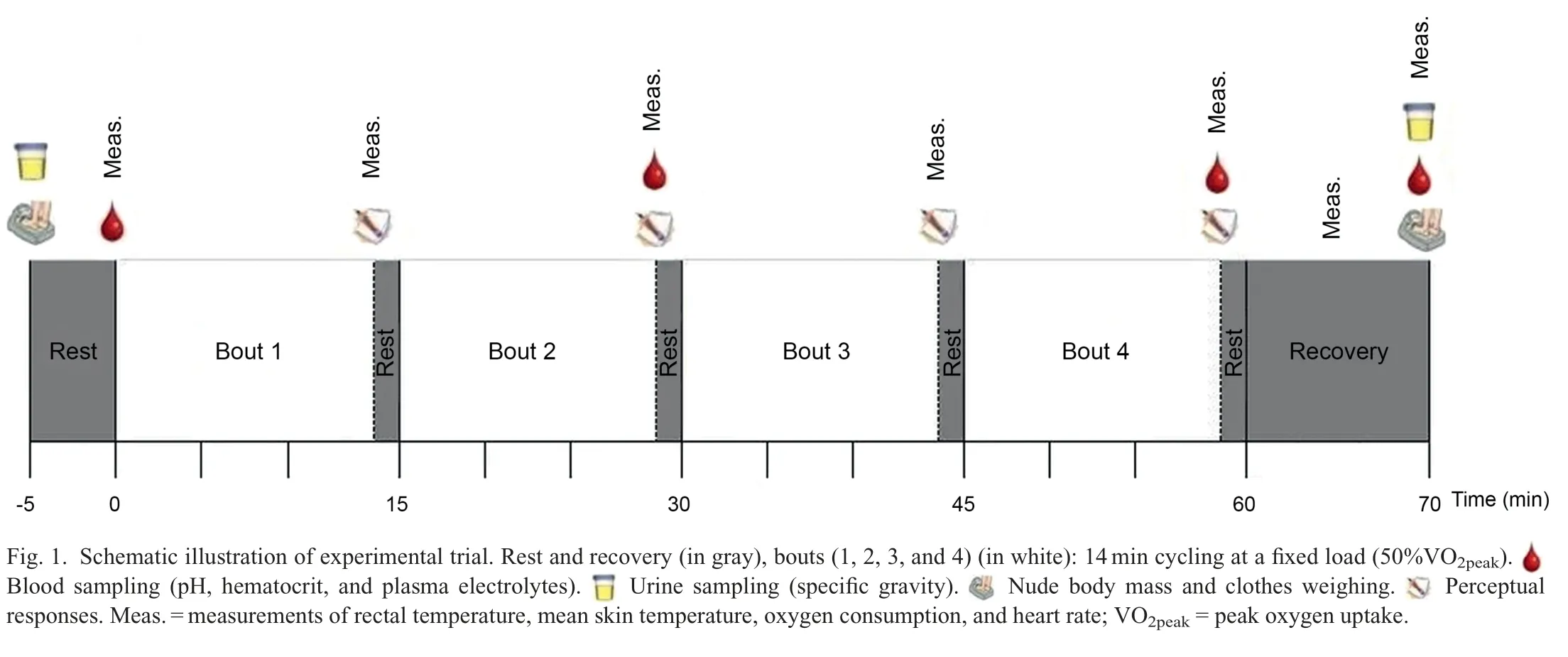

Abstract Purpose: The aim of the present study was to determine the effects of an upper body compression garment (UBCG) on thermoregulatory responses during cycling in a controlled laboratory thermoneutral environment (~23°C). A secondary aim was to determine the cardiovascular and perceptual responses when wearing the garment.Methods: Sixteen untrained participants (age: 21.3±5.7 years; peak oxygen consumption (VO2peak): 50.88±8.00 mL/min/kg; mean±SD)performed 2 cycling trials in a thermoneutral environment(~23°C)wearing either UBCG or control(Con)garment.Testing consisted of a 5-min rest on a cycle ergometer, followed by 4 bouts of cycling for 14-min at ~50%VO2peak, with 1-min rest between each bout. At the end of these bouts there was 10-min of passive recovery.During the entire protocol rectal temperature(Trec),skin temperature(Tskin),mean body temperature(Tbody),and heat storage(HS)were measured.Heart rate(HR),VO2,pH,hematocrit(Hct),plasma electrolytes,weight loss(Wloss),and perceptual responses were also measured.Results:There were no significant differences between garments for Tskin,HS,HR,VO2,pH,Hct,plasma electrolyte concentration,Wloss,and perceptual responses during the trial.Trec did not differ between garment conditions during rest,exercise,or recovery although a greater reduction in Trec wearing UBCG(p=0.01)was observed during recovery.Lower Tbody during recovery was found when wearing UBCG(36.82°C±0.30°C vs.36.99°C±0.24°C).Conclusion:Wearing a UBCG did not benefit thermoregulatory,cardiovascular,and perceptual responses during exercise although it was found to lower Tbody during recovery,which suggests that it could be used as a recovery tool after exercise.2095-2546/© 2019 Published by Elsevier B.V.on behalf of Shanghai University of Sport.This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license.(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Keywords: Body temperature;Compression garment;Cycling;Heat dissipation;Thermoregulation

1. Introduction

Studies on compression garments(CG)have recently emerged although fundamental effects on cardiovascular and thermoregulatory strain remain equivocal.1Claims from manufacturers of CG include improved performance, enhanced comfort perception,2increased muscle blood flow, and enhanced lactate removal3to name a few. Further, recent developments in these garments have led to claims of thermoregulatory benefits attributed to increased heat dissipation as a result of improved sweat efficiency. However, this remains a contentious issue, as there remains a lack of research supporting these statements.

Physiological effects of wearing lower body compression garments(LBCG)on thermoregulation and cardiovascular responses have been widely studied.1-4Goh et al.4investigated the effect of LBCG on running performance(20-min at first ventilatory threshold (VT1) followed by a run to exhaustion at maximal oxygen uptake(VO2max)velocity)in cold(10°C)and hot(32°C)environments. During the 10°C trial lower limb skin temperature (Tskin)was significantly higher when wearing CG. However, no significant differences in rectal temperature (Trec), oxygen consumption(VO2),or heart rate(HR)were observed at cold and hot conditions.Thus,the researchers concluded that LBCG had no adverse effects on running performance. Further, MacRae et al.1examined pressure and coverage effects of a full-body CG on exercise performance, cardiovascular, and thermoregulatory function during 60-min fixed load cycling at 65%VO2maxand a 6-km time trial in temperate conditions (24°C, 60% relative humidity (RH)). The full-body CG caused mild increases in thermoregulatory and cardiovascular strain(covered skin temperature and blood flow),without adversely affecting core body temperature (Tcore) or arterial pressure.

Interestingly, only a few researchers have investigated the effects of wearing upper body compression garment(UBCG).Of these,Dascombe et al.5investigated the effects of UBCG in elite flat-water kayakers on performance and physiological responses during a 6-step incremental test followed by a 4-min maximal performance test. Wearing a UBCG did not provide any significant physiological or performance benefits. Similarly, Sperlich et al.6did not find any benefits of wearing UBCG on power output,physiological and perceptual responses in well trained cross country skiers and triathletes during three 3-min sessions of double-poling sprint. However, in these studies thermoregulatory effects were not measured.Thus,to the authors'best knowledge no study has investigated the thermoregulatory effects of a heat dissipating UBCG during exercise.

Hence, the aim of the present study was to determine the effects of a UBCG on thermoregulatory responses during cycling in a controlled laboratory thermoneutral environment(~23°C).A secondary aim was to determine the cardiovascular and perceptual responses when wearing the garment. Following manufacturers' statements that consider the use of a heat dissipating UBCG would enhance heat dissipation, the use of this garment will lead to a reduced mean body temperature(Tbody).Nevertheless,based on the present literature,no positive thermoregulatory effects have been found wearing CGs.Thus,we hypothesize that the use of a UBCG will have no effect on cardiovascular responses during a 1-h lasting intermittent aerobic trial.We also hypothesize that perceptual responses will not differ between garment conditions during exercise.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Participants

Sixteen untrained participants,12 males and 4 females recreational cyclists(age:21.3±5.7 years;height:1.77±0.08 m;body mass: 73.3±7.9 kg; body surface area: 1.90±0.14 m2;peak oxygen consumption (VO2peak): 50.88±8.00 mL/min/kg;mean±SD)volunteered to participate in this study.Participants were asked to refrain from alcohol,caffeine,and strenuous activity 24 h prior to testing. They were also requested to continue with normal dietary practices during the study. All participants were informed about all of the tests and possible risks involved and provided a written informed consent form before testing. The study was approved by the Ethic Committee of the Public University of Navarre in conformity with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Clothing information

Two types of garments were used in the present study: (1)UBCG,a commercially available short sleeve UBCG made of 94% nylon, 4% elastane, 2% polypropylene that according to the manufacturer it has the quality to dissipate the heat transporting the excess of sweat away and allowing it to evaporate while exercising; and (2) control garment (Con), a commercially available short sleeve non-UBCG made of natural fabric (100% cotton). Garments were individually fitted according to manufacturer's guidelines.Volunteers wore identical shorts and sport shoes during testing period to reduce differences between trials not from the CG itself.

2.3. Study procedure

Participants reported to the laboratory on 3 occasions,separated by 2-7 days to allow rest between sessions. Experimental trials were performed at the same time of the day to minimize circadian variation.The female menstrual cycle was also taken into account to eliminate the influence of differences in hormonal status.As the females performed 2 identical trials,they acted as their own controls.More importantly,they were screened to perform the trial in either the luteal or follicular phase. Thus, if a female performed her first trial in the luteal phase, the second trial was also performed in the luteal phase. On the first visit to the laboratory,VO2peakof each participant was determined in a thermoneutral environment(20°C-23°C)using a continuous incremental test on a cycle ergometer (Ergoselect 200; Ergoline, Bitz, Germany).After a 5-min warm-up at 50W, participants began cycling at 50W with increments of 25W/min. VO2peakwas defined as the plateau in oxygen uptake despite increasing work rate (W).The criteria for determining VO2peakwere that the respiratory exchange ratio (RER) was >1.1, HR was >95% of the participant's age predicted maximum HR,or visible signs of exhaustion,such as breathlessness or the inability to maintain the required power output.

During the second and the third visits,participants performed a cycling trial with either the UBCG or the Con in a thermoneutral environment (~23°C) (22.65°C±1.04°C, 59%±5% RH,and 2.5 m/s airflow) in a randomized, counterbalanced order.The cycling trial consisted of 5-min resting on a cycling ergometer followed by 4 bouts of cycling at a fixed load (~50%VO2peak)for 14 min,with each bout separated with 1-min rest.After exercise participants rested 10 min on the cycling ergometer (Fig. 1). Post-5 and post-10-min (or recovery) were respectively determined as 5-min and 10-min passive recovery.

2.4. Measurements

2.4.1. Hydration status,body mass,and garments weight

Participants voided their bladder before exercise and at the same time a urine sample was obtained to determine urine specific gravity using a refractometer(Hannah Instruments Inc., Woonsocket, RI, USA). Following this, nude body mass was measured before and after exercise using a medical scale (Seca, Toledo, OH, USA) with accuracy±0.05 kg. Each participant wiped himself dry with a towel to remove excess sweat. The garment mass was also measured before and after exercise using a precision balance(Model 440-35N; Kern Precision Balance, Balingen, Germany) with accuracy ±0.01g. Subsequently, body weight loss (Wloss) was determined as the difference in nude body mass pre- and post-exercise (%). Sweat rate was calculated as the difference in Wloss/time (g/min). Sweat retention of the garment was determined as the difference in garments in pre-and post-exercise(g).

2.4.2. HR and respiratory gas exchange

HR was monitored continuously using an HR monitor(Model FS2c; Polar, Kempele, Finland). VO2was measured breath by breath,using open circuit spirometry(VacuMed,Ventura,CA,USA)at a sampling rate of 10s.The gas analyzer was calibrated before each trial using a calibration gas mixture 15%O2,5%CO2(Praxair,Madrid,Spain)and the flowmeter was calibrated using a Jaeger 3L calibration syringe(VacuMed).

2.4.3. Trec,Tsk,and Tbody

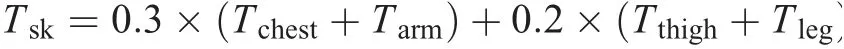

Trecwas recorded using a sterile rectal thermistor (Model 4600 precision thermistor thermometer; YSI, Yellow Springs,OH, USA) inserted 10 cm through the anal sphincter.4Four fast response skin temperature probes (Model PS-2135;PASCO, Roseville, CA, USA) were placed using adhesive mylar foam covers(Model PS-2525;PASCO)at 4 sites:chest,arm, thigh, and leg. Tskdata were continuously recorded with a data logger(NI USB-6259 BNC;National Instruments,Austin,TX,USA)connected to a computer.A LabVIEW program(LabVIEW, 2010; National Instruments) was used to record Tsk.Tskwas calculated using the following formula:7

Tbodywas calculated using the following formula:8

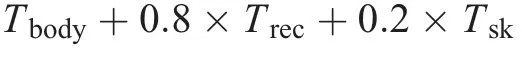

2.4.4. Heat storage(HS)

HS in body tissues was calculated from the formula:9

Where 0.97 is the specific heat of tissue(W/h/kg/°C),BWpreis the pre-exercise body mass (kg), (Tbpost-Tbpre) represents the increase in Tbodyduring exercise (°C), SA is the DuBois surface area(m2)of the body10and t is the elapsed time(h).

2.4.5. Blood analysis

Capillary blood samples (95 μL)from the right hand index finger were sampled before the cycling trial,at rest,at the end of Bout 2, at the end of Bout 4, and at recovery (post-10).Blood samples were collected in heparinized capillaries and immediately analyzed in a medical Easystat®blood analyzer(Medica Corporation, Bedford, MA, USA) for concentration in plasma variables(pH,hematocrit(Hct),Sodium(),and Potassium()).

2.4.6. Perceptual data

The participant's rating of perceived exertion(RPE)using a Borg 6-20 scale11and subjective sensation in respect of thermal sensation, shivering/sweating sensation and clothing wettedness sensation12were recorded at the end of each bout.Ratings of thermal sensation ranged from 1 (very cold) to 9(very hot),shivering/sweating sensation ranged from 1(vigorously shivering) to 7 (heavily sweating) and clothing wettedness sensation ranged from 1(dry)to 4(wet).

2.5. Statistical analyses

Data are presented as means±SD. A repeated-measures(garment condition×time)analysis of variance(ANOVA)was used to determine significant differences between the respective conditions (UBCG and Con). Post hoc analysis was conducted with a Tukey's honest significant test to determine individual significant differences.SPSS Version 17.0(SPSS Inc.,Chicago,IL,USA)Statistical significance was set as p <0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Pre-exercise hydration condition,weight loss,and sweat rate

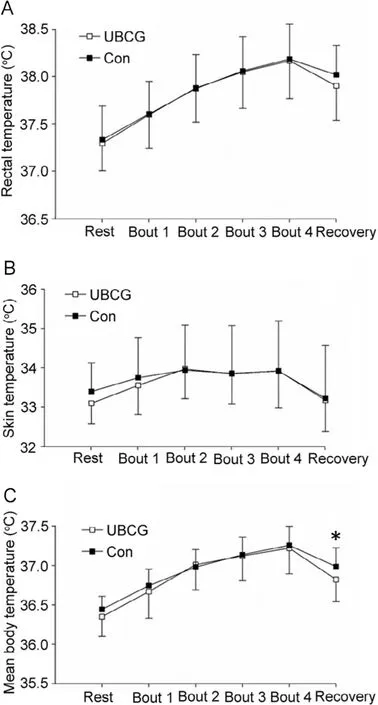

Fig. 2. Rectal (A), skin (B), and mean body temperature (C) during experimental trial. *p <0.05 significantly different between garment conditions.Values are presented as mean±SD.Con=control;UBCG=upper body compression garment.

Euhydration before the trial was confirmed with a urine specific gravity <1.020 as indicated by National Collegiate Athletic Association.13No significant differences in Wloss(1.0%±0.2%vs.1.2%±0.3%,UBCG and Con,respectively)or sweat rate (12.8±3.2 g/min vs. 14.2±5.0 g/min) were observed between garment conditions at the end of the trial.

3.2. Garments weight and sweat retention in garments

UBCG was significantly heavier than Con before trial(198±14 g vs.135±11 g,p <0.001).Furthermore,at the end of the trial, significantly higher sweat retention in UBCG was found(6.47±4.39 g vs.3.71±1.93 g,p=0.04).Nevertheless,when sweat retention in garments was normalized to sweat/g to garment mass, no significant differences were found between garment conditions(p=0.50).

3.3. Thermoregulatory responses

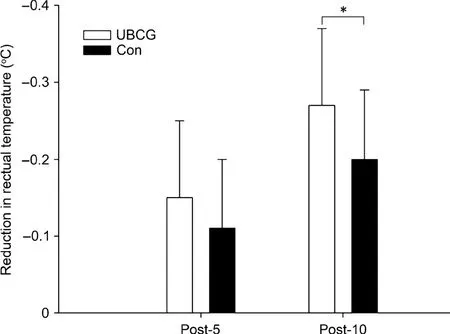

Participants reached a similar Trec(38.17°C±0.40°C vs.38.19°C±0.37°C, UBCG and Con, respectively) and Tskin(33.92°C±0.94°C vs.33.92°C±1.28°C)at the end of exercise(Fig. 2A and B). No difference in HS (p=0.54) was found at the end of exercise between garment conditions. However a greater and significantly lower Tbody(36.82°C±0.30°C vs.36.99°C±0.24°C, p=0.03) (Fig. 2C) and rate of reduction in Trec(-0.27°C±0.10°C vs. -0.20°C±0.10°C; p=0.01)(Fig. 3) were found when wearing UBCG over the recovery period.

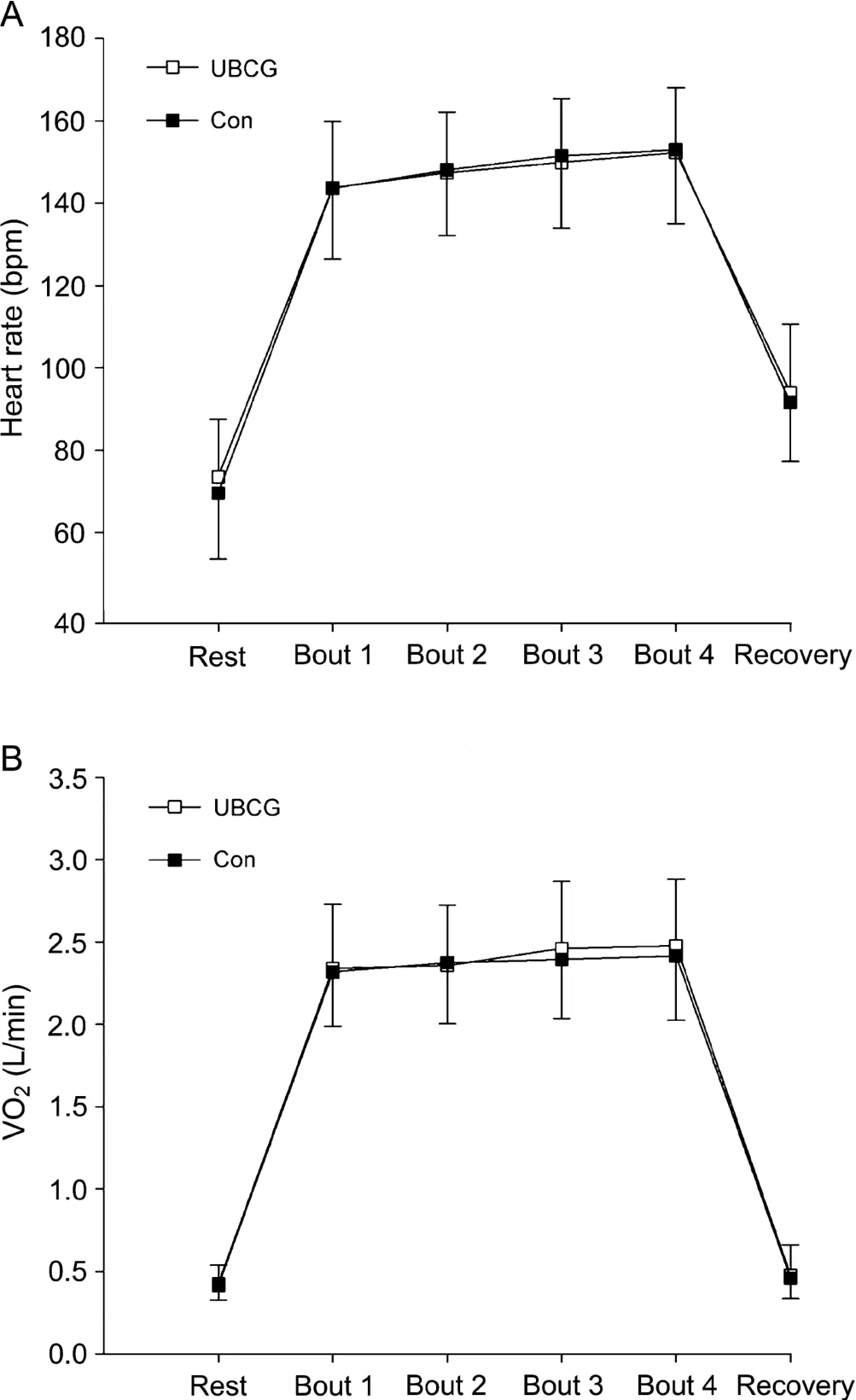

3.4. Cardiorespiratory responses

Cardiorespiratory responses increased(p <0.001)over time in both garment conditions from rest until the end of exercise although no differences in HR and VO2between garment conditions were observed over the trial(Fig.4).

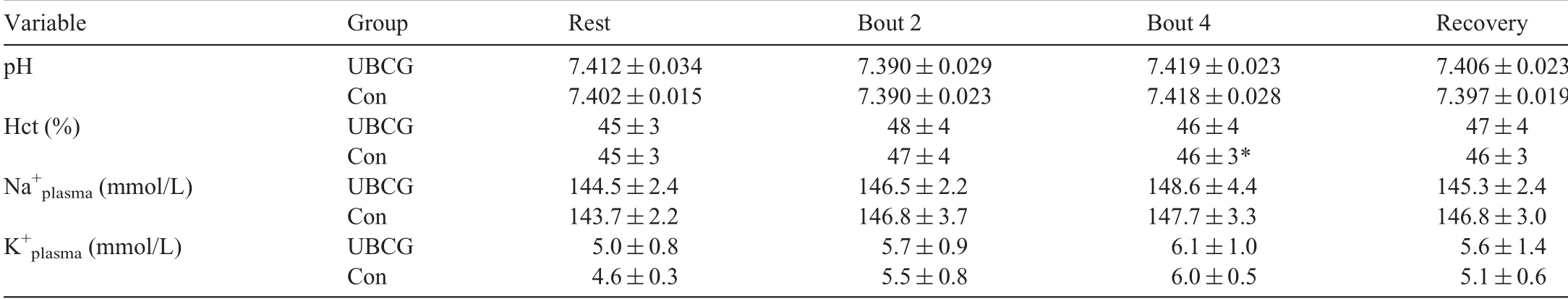

3.5. Blood analysis

No significant differences in pH, Hct,, andwere observed between garment conditions during the trial(Table 1).Hct increased significantly from rest to the end of exercise in Con(p=0.04)but not in UBCG(p=0.52).

3.6. Perceptual responses

All perceptual responses increased (p <0.05) significantly over time for both garment conditions.No significant differences in RPE, thermal sensation, shivering/sweating sensation,and clothing wettedness sensation were found over the trial despite different garment conditions.

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to evaluate the effects of a heat dissipating UBCG during cycling at a submaximal intensity on thermoregulatory, cardiovascular, and perceptual effects. To our knowledge, no previous research studying physiological effects of wearing a UBCG during cycling in a thermoneutral environment have been performed. The main finding of the present study was that wearing a UBCG helped lowering Tbodyduring the recovery process in a thermoneutral environment when compared to a similar control garment.

Fig. 3. Reduction in rectal temperature during recovery period. Post-5 and Post-10, reduction in rectal temperature after 5 min and 10 min of passive recovery,respectively.*p <0.05 significantly different between garment conditions. Values are presented as mean±SD. Con=control; UBCG=upper body compression garment.

Fig. 4. Heart rate (A) and oxygen consumption (B) during experiental trial.Values are presented as mean±SD.Con=control;UBCG=upper body compression garment;VO2=oxygen consumption.

It was initially hypothesized that wearing a UBCG would not have an effect on thermoregulatory responses. Present hypothesis was consistent with previous research that had not found differences in thermoregulatory effects when wearing lower body compression garments in core temperature,1,3,4skin temperature1,14and/or mean body temperature.14However,in the present study,a lower Tbody(Fig.2C)and a greater rate of reduction in Trec(Fig. 3) were observed wearing the UBCG during the recovery period. Compression garments have been suggested as a possible method that could help in athletes' recovery after high intensity training15,16but no previous thermoregulatory benefits had been observed before.Furthermore,it has been shown that reducing core temperature prior to the onset of exercise increases the body's ability to store endogenous and exogenous heat and therefore improves exercise performance,17consequently a lower Tbodyin the recovery process could probably be beneficial in the continuation of the exercise after a short term recovery period. Conversely, Goh et al.4and Houghton et al.3did not find significant differences in core temperature when wearing compression garments, they did however observe a significant higher skin temperature at 10°C and 17°C, respectively. Both authors suggested that higher skin temperature could be due to the insulation effect of the garments that reduced air permeability.In the present study volunteers received a constant airflow(2.5 m/s)toward the chest that may have allowed a better permeability of the air in the garments.

Researchers studying thermoregulatory effects between synthetic or natural fabrics have not found differences in exercising rectal temperature in different ambient temperatures.18Exercising at a submaximal intensity in a thermoneutral environment neither the compression exerted on the skin nor the synthetic material were able to dissipate the heat better than a control garment made of natural fabrics. If the latter 2 elements(pressure and material)were not able to reduce Tbodyduring exercise another reason regarding greater reduction in rectal temperature during recovery must exist. Perhaps the greater contact of the garment to the skin together with the constant airflow could have transferred the heat better from the body to the ambient in the UBCG condition.

HR during the trial did not differ between the 2 conditions(Fig. 4). This is consistent with previous research that did not find significant differences in HR wearing either compression garments or non-compression garments when exercising in a thermoneutral environment.2,4-6,19,20Changes in HR between compression garments or non-compression garments during exercise have been shown to be similar even during cycling,20,21running,2,19,22kayaking,5or skiing.6During the recovery period, no significant reductions in HR between garment conditions have been recorded in previous studies.19,23

Table 1 Blood samples absolute values for fingertip blood samples at rest,during exercise(Bouts 2 and 4)and recovery wearing UBCG or Con(mean±SD).

The findings from this study suggest that the use of compression garments during exercise or passive recovery in thermoneutral environments do not help in mitigating cardiovascular strain better than a non-compression garment.

Bringard et al.22reported lower aerobic energy cost when wearing compression tights at a submaximal exercise intensity(12 km/h). The authors suggested that wearing compression tights during running exercise could enhance overall circulation(venous blood flow) and decrease muscle oscillations to promote a lower energy cost. Bringard et al.24also evaluated the effects of compression tights on calf muscle oxygenation and venous pooling at resting conditions using a near-infrared spectroscopy and reported positive effects wearing them. However in the present study no changes in VO2during exercise were observed wearing UBCG. Pressure exerted on the upper limb(non-exercising limb) during cycling could have not achieved these expected results as reported by Bringard et al.22when wearing LBCG. The present results are consistent with the recent findings by Dascombe et al.5and Sperlich et al.6who did not observe differences in oxygenation measures (NIRS and VO2) when evaluated the effects of a UBCG on intermittent exercise.Hence,we conclude that wearing UBCG did not lower VO2values that could have increased blood flow during cycling at a submaximal intensity in a thermoneutral environment.Although, the present study did not measure the level of pressure exerted on the compressed limbs according to the present results we cannot support the idea that wearing UBCG could promote a lower energy cost lowering VO2values when exercising at moderate intensities.

Several authors have concluded that dehydration increases HS during exercise because dry heat loss is reduced.25,26In the present study dehydration(Wloss)was only 1.0%-1.2%and did not differ between garment conditions. Moreover, plasma volume decreases when a person is severely dehydrated27and dehydration of 2% of body weight could lead to an increase in core temperature and cardiovascular strain.28Wearing UBCG did not(p=0.52) increase Hct significantly over time whereas wearing the Con garment did (p=0.04). Pressure exerted on the skin is known to produce an inhibitory effect on sweating rate.29Therefore, pressure exerted by UBCG on the skin may have reduced sweat rate,limiting the amount of sweat that left from the body to the skin and preventing participants from severe dehydration.Nevertheless, in this study no differences in Hct,,Wloss,or sweat rate were observed at the end of exercise(Table 1), therefore further studies of exercise lasting >1h are needed to confirm the effects of UBCG on dehydration.

Despite participants having a previous knowledge about the possible benefits of wearing UBCG (they were not blinded to the garment condition), no differences in perceptual responses were observed. The possibility that the garment could have a positive psychological effect on participants did not interfere in perceptual responses.Clothing wettedness and shivering/sweating sensation did not differ between garment conditions.Cotton has shown greater water absorption,which has been consistently shown for natural fabrics compared to synthetic fabrics.30,31Paradoxically greater sweat retention was observed in the UBCG after the trial probably due to a greater weight of the garment that accumulated bigger amounts of sweat. Nevertheless, differences did not exist when normalized to sweat/g to garment mass. As well as thermoregulatory and cardiorespiratory responses were not significantly different between 2 conditions at the end of exercise,thermal sensation and RPE also did not differ between garment conditions which means that during exercise while physiological differences remained similar between garments,psychological responses remained unaltered.

5. Conclusion

The results of this study appear to demonstrate the efficacy of wearing a heat dissipating UBCG during recovery process,which suggests that it might be a useful thermoregulatory tool after exercise.The use of a UBCG may be beneficial for intermittent exercise-based sports where there is a player rotation system such as, volleyball, handball, futsal; or individual sports with resting periods throughout the game(tennis).

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank all of the participants for their participation,which made this study possible.This study was supported by the Public University of Navarre.

Authors'contributions

ILA participated in the design of the manuscript,carried out data collection, performed the statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript;NT helped to draft the manuscript and language editing; RAJ conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript,and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Journal of Sport and Health Science2019年5期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2019年5期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Biomechanics of ankle giving way:A case report of accidental ankle giving way during the drop landing test

- Dynamic knee valgus kinematics and their relationship to pain in women with patellofemoral pain compared to women with chronic hip joint pain

- Influences of load carriage and physical activity history on tibia bone strain

- Effects of intermittent sprint and plyometric training on endurance running performance

- The relationship between transport-to-school habits and physical activity in a sample of New Zealand adolescents

- Cardiorespiratory fitness and cancer in women:A prospective pilot study