负性生活事件与青少年早期抑郁的关系:COMT基因Val158Met多态性与父母教养行为的调节作用*

王美萍 郑晓洁 夏桂芝 刘迪迪 陈 翩 张文新

负性生活事件与青少年早期抑郁的关系:基因Val158Met多态性与父母教养行为的调节作用

王美萍 郑晓洁 夏桂芝 刘迪迪 陈 翩 张文新

(山东师范大学心理学院, 济南 250358)

采用环境×基因×环境(E×G×E)研究设计, 以637名青少年为被试, 考察了负性生活事件、基因Val158Met多态性和父母教养行为对青少年早期抑郁的影响。结果发现:负性生活事件对青少年早期抑郁具有显著正向预测作用, 且基因Val158Met多态性和父亲积极教养行为在其中起调节作用, 但该调节作用仅存在于男青少年群体中:在携带Val/Val基因型的男青少年中, 当父亲积极教养行为水平较低时, 青少年的抑郁水平随负性生活事件的增多而显著上升, 当父亲积极教养行为水平较高时, 负性生活事件对抑郁无显著预测作用; 在携带Met等位基因的男青少年中, 上述交互作用不显著。

负性生活事件; 抑郁;基因Val158Met多态性; 父母教养行为; 性别差异

1 问题提出

抑郁是个体常见的心理健康问题之一。由于其在青少年早期的发生率高, 危害大(Zhang et al., 2015; 王美萍, 张文新, 陈欣银, 2015; Natsuaki, Biehl, & Ge, 2010), 因而青少年早期抑郁的影响因素及其作用机制一直是心理学领域的重要研究内容。既有研究表明, 个体所经历的负性生活事件是抑郁的重要预测因素, 负性生活事件水平越高, 其患抑郁的可能性越高(Chen, Li, & McGue, 2012; Stikkelbroek, Bodden, Kleinjan, Reijnders, & Van Baar, 2016; Suzuki et al., 2018; Hetolang & Amone-P’Olak, 2018)。随着成长环境范围的扩大, 个体在青少年期所经历的负性生活事件相较于童年期显著增加(Timmermans, van Lier, & Koot, 2010; Roberts, English, Thompson, & White, 2018)。尽管如此, 现实告诉我们, 并非所有经历负性生活事件的个体都会表现出抑郁症状, 经历同样水平负性生活事件的个体, 也不一定都表现出同等程度的抑郁, 二者的关系很可能还会受到其他因素的调节。

来自行为遗传学领域的研究表明, 抑郁的发生具有重要的遗传基础, 其遗传率约为24%~55%;(catechol-O-methyltransferase, 儿茶酚胺氧位甲基转移酶)基因是抑郁的重要候选基因(Rózycka et al., 2016; Domschke et al., 2010; 曹丛, 王美萍, 曹衍淼, 纪林芹, 张文新, 2017)。基因位于22号染色体长臂1区1带2亚带(22q11.2), 它是儿茶酚胺(包括肾上腺素、去甲肾上腺素和多巴胺)的主要代谢酶(王美萍, 张文新, 2014)。该基因编码区至少有8个单核苷酸多态性变异, 其中Val158Met多态性(rs4680多态性)是最为常见的功能性位点, 且Val等位基因编码的COMT活性是Met等位基因的3~4倍(Lachman et al., 1996; 王美萍, 张文新, 2014)。目前已有研究考察了基因Val158Met多态性与负性生活事件对抑郁的交互影响, 但研究结论尚存在分歧。有的研究发现, 与携带Met/Met基因型个体相比, 携带Val等位基因的个体在经历负性生活事件后抑郁水平更高(Hosang, Fisher, Cohen-Woods, Mcguffin, & Farmer, 2017)。有的研究则表明基因Val158Met多态性和负性生活事件对抑郁不存在显著的交互作用(Evans et al., 2010)。其原因可能是除了基因Val158Met多态性与负性生活事件外, 抑郁还会受到其他因素的影响。

发展系统论的观点(Bronfenbrenner, 1979)提示我们, 除了个体自身遗传特征外, 个体所处的家庭生态系统因素, 譬如父母教养行为, 也会对青少年早期抑郁的发生具有重要影响。现有研究亦表明父母积极教养行为(如父母支持、温情等)和消极教养行为(如惩罚、敌对等) (Bilsky et al., 2013; Healy & Sanders, 2018; Tucker, Sharp, Gundy, & Rebellon, 2018; Tang, Deng, Du, & Wang, 2018)均与青少年抑郁存在显著关联。然而, 关于负性生活事件对抑郁的影响是否会同时受到基因Val158Met多态性和父母教养行为的调节, 即父母教养行为能否在一定程度上缓冲或加剧负性生活事件对抑郁的影响, 且该影响是否会因个体基因型的不同而存在差异的问题, 以往研究尚未进行有关探讨。鉴于此, 本研究的目的之一是采用环境×基因×环境设计, 重点考察基因Val158Met多态性和父母教养行为在负性生活事件和抑郁间的调节作用及其具体表现形式。

此外, 众多研究表明遗传与环境对抑郁的交互作用存在性别差异(Priess-Groben & Hyde, 2013; Nyman et al., 2011; Uddin, de los Santos, Bakshis, Cheng, & Aiello, 2011)。譬如, 一项以5225人(男性2509人, 女性2716人)为被试的研究表明,基因Val158Met多态性与早期环境压力交互预测抑郁, 且该交互作用只存在于男性中, 具体表现为携带Val等位基因的男性在经历了早期环境压力后表现出更高的抑郁水平(Nyman et al., 2011)。然而关于负性生活事件、基因Val158Met多态性和父母教养行为的交互作用是否也存在性别特异性的问题尚不清楚。

简言之, 本研究拟探查以下两个问题:(1)负性生活事件对抑郁的影响是否同时受到基因Val158Met多态性和父母教养行为的调节, 如果存在, 其具体表现是什么?(2)上述调节作用是否存在性别差异?

2 研究方法

2.1 样本

根据以往相关研究, 达到显著性水平(0.05)的基因与环境交互效应的效果量一般在0.01~0.03。本研究以该范围内的效果量为基础, 采用G*Power 3.1.9.2软件进行了分析, 结果显示要达到80%以上的统计功效, 约需要380~1100的被试量, 所以我们的计划样本量约为650人。由于本研究是以班级为单位选取被试, 因此实际取样637人。具体来说, 我们选取山东省济南市2所中学7~9年级的637名学生作为被试。其中男生344人, 女生293人, 平均年龄为13.33岁(= 1.01)。独生子女418人, 非独生子女219人。父母的文化程度主要为中等教育学历(包括初中和高中), 父亲和母亲分别占53.92%和58.76%。家庭月收入1000元以下的占0.46%, 1000~3000元的占13.82%, 3000~6000元的占31.11%, 6000元以上的占53.69%。

2.2 研究工具

2.2.1 抑郁量表

采用Radlof编制的流调中心抑郁量表(CES-D) (汪向东, 1999)。该量表共20个项目, 采用4点记分(1—偶尔或无, 2—有时, 3—一半时间, 4—多数时间)。得分越高, 代表抑郁水平越高。量表的Cronbach信度系数为0.88。

2.2.2 负性生活事件量表

采用刘贤臣编制的青少年生活事件量表(汪向东, 1999)。原量表包括26个题目, 内容均为可能对青少年带来影响的负性生活事件。其中有5个题目与家庭有密切关系, 所以为了避免负性生活事件与父母教养行为的测量不独立, 本研究中删除了这5个项目。该量表要求被试自我报告每一事件在近12个月内是否发生, 若发生, 则采用5点计分来评判其对自身的影响程度, 1~5代表“没有影响”到“极重度影响”。得分越高, 代表负性生活事件对自身的影响越大。量表Cronbach信度系数为0.91。

2.2.3 父母教养行为问卷

由项目组自行编制, 且具有良好的信效度。该问卷由青少年自我报告。问卷包括积极教养行为和消极教养行为两个维度。积极教养行为的测查内容包括父母对孩子的情感温暖、鼓励和支持引导, 共计10个题目; 消极教养行为的测查内容包括拒绝和高控制/惩罚, 共计13个题目。该问卷采用5点计分, 1~5代表“几乎从不”到“几乎总是”。某种教养行为得分越高, 表示该教养行为越多。两种教养行为的Cronbach信度系数均为0.95。

2.2.4 基因提取与分型

采用唾液样本提取DNA。唾液样本采集以班级为单位, 所有被试一次性采样成功率约为97%, 剩余3%在二次采样后也达到指定要求。基因分型利用美国Sequenom公司的MassARRAY系统完成。基因引物为F: ACGTTGGATGTAGGTGTCAATGGCCTCCAG, R: ACGTTGGATGTCATGGGTGACACCAAGGAG。分型结果由MassARRAY RT软件系统(版本号3.0.0.4)实时读取, 并由Mass ARRAY Typer软件系统(版本号3.4)完成分析, 基因分型成功率为100%。

2.3 施测程序

施测过程分为两个阶段进行。第一阶段:在与学校领导、班主任老师协调好的前提下, 以班级为单位组织学生完成抑郁量表、负性生活事件量表和父母教养行为量表的测查。第二阶段:以班级为单位采集被试的唾液。由班主任老师通知学生在采集唾液样本前30 min不得进食、饮水、嚼口香糖等, 采集过程大约为35 min。采集完成后, 交由某生物科技公司对唾液样本进行基因分型。施测过程的主试人员均由接受过严格培训的心理学专业老师和研究生担任, 问卷的测查及唾液样本的采集均取得了学生、学校领导和班主任的同意。本研究也获得山东师范大学伦理委员会批准。

2.4 数据处理与分析

运用SPSS 21.0和CMA 3.0对数据进行处理和分析。在观察各变量的分布形态时发现父母消极教养行为得分均呈正偏态分布, 故首先对其进行正态化处理。采用皮尔逊积差相关分析各变量的关联程度时, 对基因型(Val/Val = 0, Met/Met & Met/Val = 1)和性别(男= 0, 女= 1)变量进行虚拟编码处理。在进行回归分析时, 对父亲和母亲的积极、消极教养行为分别建模; 变量及交互项的处理采用Burrill的正交法(1998)。与中心化法相比, 该方法能更好地解决变量间的多重共线性问题。此外, 为确保统计结果的可靠性, 控制Ι类错误发生率, 我们采用Benjamini-Hochberg程序(1995)对所有回归分析结果的显著性水平进行校正。最后使用内部验证性分析和元分析两种方法(Bakermans-Kranenburg & van Ijzendoorn, 2011; Cao et al., 2018)进一步检验研究结果的稳定性与可靠性。

3 结果

3.1 Hardy-Weinberg平衡的吻合度检验

基因Val158Met多态性基因型分布如下:Val/Val = 53.69% (342人), Met/Val = 38.93% (248人), Met/Met = 7.39% (47人)。该位点的观测值与期望值吻合良好(= 0.05,= 1,> 0.05), 符合Hardy-Weinberg平衡。由于Met/Met基因型携带者人数较少, 所以参照以往同类研究(Comasco et al., 2011, 曹丛等, 2017), 将Met/Met和Met/Val基因型进行合并, 统称为Met等位基因携带者(295人)。

3.2 变量的描述统计量与相关分析结果

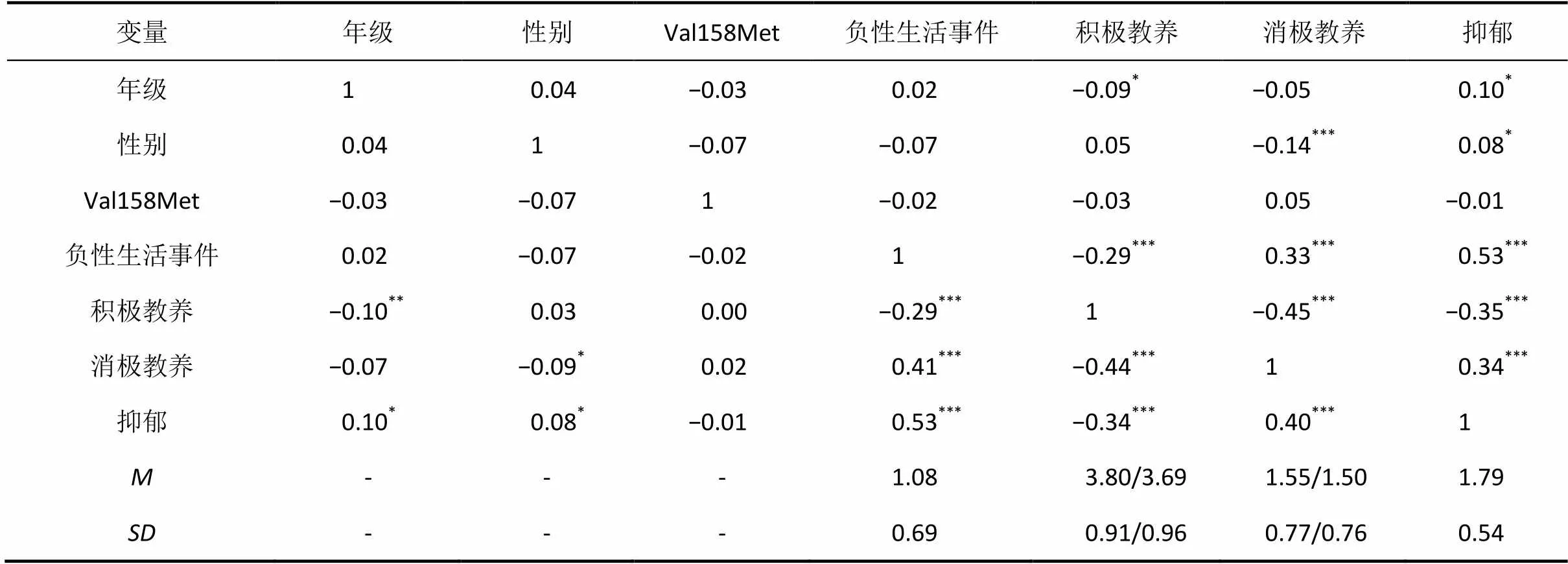

皮尔逊积差相关分析结果显示(见表1), 年级与父母积极教养行为呈显著负相关, 和抑郁呈显著正相关, 即随着年级的增长, 父母的积极教养行为减少, 青少年的抑郁水平显著上升; 性别与父母消极教养呈显著负相关, 与抑郁显著正相关, 表明父母对女青少年的消极教养行为要显著少于男青少年, 但女生的抑郁程度要高于男生, 因此在后续的分析中将年级作为协变量进行控制, 同时依据性别进行分组分析; COMT基因Val158Met多态性基因型的分布和青少年的年级、性别、负性生活事件、父母积极与消极教养行为、抑郁得分均无显著相关。此外, 负性生活事件与抑郁呈显著正相关, 父母积极、消极教养行为分别与抑郁呈显著负相关和正相关。

表1 主要变量的描述统计量及相关分析结果

注:< 0.05,< 0.01,< 0.001; 对角线之上的相关系数是关于父亲的, 之下是关于母亲的, /左右分别代表父亲和母亲教养的信息。

3.3 抑郁对负性生活事件、COMT基因Val158Met多态性和父母教养行为的分层回归分析

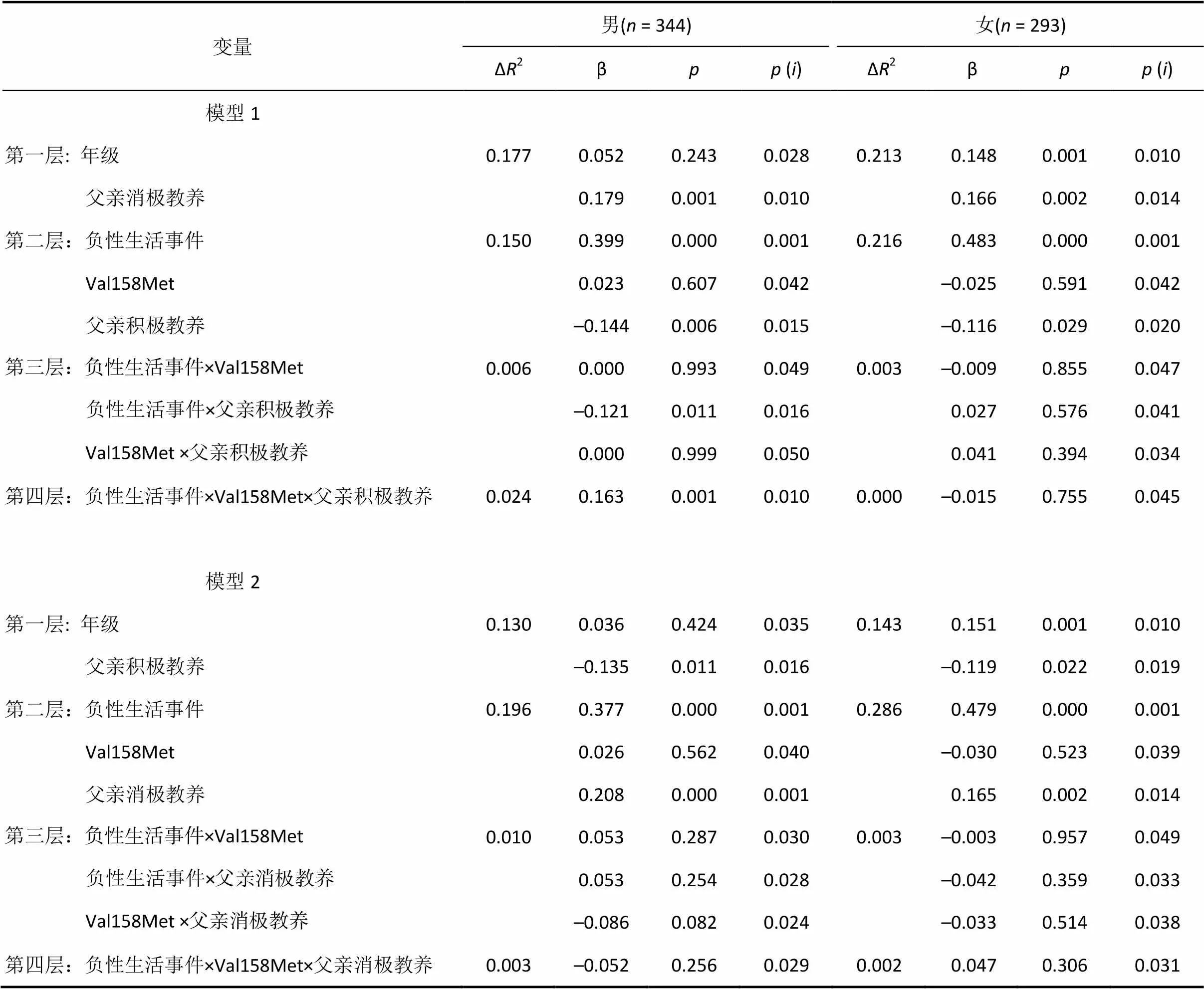

以性别为分组变量, 抑郁为因变量, 负性生活事件、基因Val158Met多态性和父母教养行为为预测变量进行分层回归分析, 方程具体建构方法如下:(1)第一层:年级、父母积极或消极教养行为作为控制变量; (2)第二层:负性生活事件、基因、父母积极或消极教养行为; (3)第三层:第二层变量的两因素交互项; (4)第四层:第二层变量的三因素交互项。采用Benjamini-Hochberg 程序校正后的结果表明(见表2和表3)。

基因Val158Met多态性对抑郁的主效应不显著, 负性生活事件、父母积极和消极教养行为对抑郁均存在显著或边缘显著的主效应。此外, 仅在男青少年中, 负性生活事件对抑郁的影响受到基因Val158Met多态性与父亲积极教养行为的调节(β = 0.16,= 3.50,0.05):在携带Val/Val基因型的男青少年中, 父亲积极教养行为显著调节负性生活事件对抑郁的影响(β = −0.25,= −3.86,0.05), 具体表现为负性生活事件仅能正向预测低父亲积极教养行为条件下男青少年的抑郁(β = 0.74,= 4.86,0.05), 但对高父亲积极教养行为条件下的男青少年抑郁无显著预测作用(β = 0.09,= 0.50,0.05); 此外, 在携带Met等位基因的男青少年中, 父亲积极教养行为在负性生活事件与抑郁间的调节作用不显著(β = 0.04,= 0.62,0.05) (见图1)。

另外, 负性生活事件、基因Val158Met多态性与母亲积极教养行为(β = 0.09,= 1.94,=0.05)和母亲消极教养行为(β = −0.08,= −1.74,=0.08) 对男青少年抑郁也存在边缘显著三因素交互作用:对那些携带Val/Val基因型的男青少年而言, 低水平的母亲积极教养行为(β = 0.58, t = 2.85, p < 0.05)和高水平的母亲消极教养行为(β = 0.48, t = 2.72, p < 0.05)会增强负性生活事件对男青少年的消极影响, 但是高水平的母亲积极教养行为(β = 0.37, t = 1.84, p > 0.05)和低水平的母亲消极教养行为(β= 0.27, t = 1.88, p > 0.05)能够缓冲负性生活事件的不利影响。但在携带Met等位基因的男青少年中, 负性生活事件与母亲积极教养行为(β = 0.01, t = 0.12, p > 0.05)和母亲消极教养行为(β = −0.19, t = −1.01, p > 0.05)的交互作用不显著。

表2 抑郁对青少年的负性生活事件、COMT基因Val158Met多态性与父亲教养行为的分层回归分析

注:表示原始的值,()为采用Benjamini-Hochberg程序(1995)校正后的显著性水平临界值, 若≤ p (), 则结果显著。(下同)

表3 抑郁对青少年的负性生活事件、COMT基因Val158Met多态性与母亲教养行为的分层回归分析

图1 负性生活事件、COMT基因Val158Met多态性与父亲积极教养行为对男青少年抑郁的交互作用

3.4 内部验证性分析与元分析

为了检验负性生活事件×基因Val158Met多态性×父亲积极教养行为结果的稳定性和可靠性(负性生活事件×基因Val158Met多态性×母亲积极教养行为和负性生活事件×基因Val158Met多态性×母亲消极教养行为的结果仅达到边缘显著, 所以此处没有做进一步的验证分析), 我们采用内部验证性分析法把总样本随机分为两部分:子样本1(= 315)和子样本2(= 322)。结果显示在子样本1中, 负性生活事件×基因Val158Met多态性×父亲积极教养行为对抑郁的交互作用在男青少年中表现为边缘显著(β = 0.12,= 1.69,0.09), 在子样本2中上述三者交互作用达到显著性水平(β = 0.16,= 2.41,0.05)。进一步的分析仍显示只有在携带Val/Val基因型的男青少年中, 负性生活事件和父亲积极教养行为对抑郁存在显著的交互作用(子样本1: β = −0.25,= −3.86,0.01; 子样本2: β = −0.35,= −3.52,< 0.01), 在父亲积极教养水平较低的情况下, 负性生活事件对男青少年抑郁具有显著正向预测作用(子样本1: β = 0.74,= 4.86,0.001; 子样本2: β = 0.77,= 4.70,= 0.001), 但在父亲积极教养水平较高的情况下, 负性生活事件对男青少年抑郁的预测作用不显著(子样本1: β = 0.09,= 0.50,0.05; 子样本2: β = 0.43,= 1.85,0.05)。上述研究发现与总样本的研究结果较为一致。此外, 我们采用Bootstrap法在男青少年样本中进行500次的随机抽样后, 结果发现负性生活事件×基因Val158Met多态性×父亲积极教养行为对抑郁交互作用的各项指标为:= 0.083,= 0.028,= 0.006, 95% CI = 0.027, 0.142。因此可以看出, 负性生活事件×基因Val158Met多态性×父亲积极教养行为三者交互作用于抑郁的Bootstrap结果依然是稳定且显著的。

参照已有研究(Bakermans-Kranenburg & van Ijzendoorn, 2011; Cao et al., 2018), 我们进一步采用CMA 3.0软件进行元分析, 以对两个子样本中负性生活事件、基因Val158Met多态性与父亲积极教养行为三者对男青少年抑郁交互作用的综合效应(combined effects)进行考察, 结果发现:对于携带Val/Val基因型的男青少年, 当父亲积极教养行为水平较低时, 负性生活事件对抑郁具有显著正向预测效应(= 0.82, 95% CI = 0.61, 0.92,< 0.001), 当父亲积极教养水平较高时, 负性生活事件对抑郁无显著预测效应(= 0.30, 95% CI = −0.06, 0.60,> 0.05), 在携带Met等位基因的男青少年中, 无论父亲积极教养行为水平低(= 0.32, 95% CI = −0.03, 0.60,> 0.05)和高(= 0.22, 95% CI = −0.19, 0.57,> 0.05), 负性生活事件对抑郁的预测效应均不显著。Q检验结果显示, 两个子样本同质(s ≤ 1.07,= 1,s > 0.05)。

4 讨论

本研究采用E×G×E的研究设计, 首次考察了负性生活事件、基因Val158Met多态性和父母教养行为对青少年早期抑郁的影响, 结果显示负性生活事件能够有效影响抑郁水平, 且基因Val158Met多态性和父亲积极教养行为在其中起调节作用, 但该调节作用只存在于男青少年群体中。

与以往研究结论相一致(Chen et al., 2012; Stikkelbroek et al., 2016; Suzuki et al., 2018; Hetolang & Amone-P’Olak, 2018), 本研究发现无论是男青少年, 还是女青少年, 其经历的负性生活事件水平越高, 抑郁程度就越重。而且, 即使在控制年级和父母教养行为的效应后, 负性生活事件仍然可以显著正向预测青少年抑郁。这说明负性生活事件确实是青少年抑郁的重要预测因素。

尽管如此, 负性生活事件对青少年抑郁的影响程度仍存在一定个体差异。我们的多方法分析结果进一步表明, 负性生活事件对抑郁的影响受到基因Val158Met多态性和父亲积极教养行为的调节。具体表现为对那些携带Val/Val基因型的男青少年而言, 在父亲积极教养行为水平较低的情况下, 其抑郁水平随负性生活事件的增多而明显上升, 但在父亲积极教养行为水平较高的条件下, 负性生活事件对其抑郁没有显著作用。这可能说明低水平的父亲积极教养行为会加剧负性生活事件对携带Val/Val基因型男青少年的消极影响, 但高水平的父亲积极教养行为则能有效缓冲负性生活事件对他们的不利影响。然而, 对于携带Met等位基因的男青少年而言, 父亲积极教养行为在负性生活事件和抑郁间的调节作用并不显著。在关于母亲积极教养行为和消极教养行为的分析中, 我们也发现了类似的三者交互作用趋势。

这与以往部分研究结果相符合(Drury et al., 2010; Vai et al., 2017)。譬如一项以儿童为被试的研究发现成长于抚养机构的孩子中, 携带Val/Val基因型的个体比携带Met等位基因的表现出更高的抑郁水平(Drury et al., 2010)。另一项研究也表明携带Val/Val基因型的双向情感障碍患者更易受到消极情绪刺激的影响(Vai et al., 2017)。现有资料显示(Stein et al., 2006, Antypa, Drago, & Serretti, 2013, Matsumoto et al., 2003, Karoum, Chrapusta, & Egan, 1994),基因Val158Met多态性对前额区域(多巴胺转运体的分布较少)中的多巴胺水平起关键调节作用。与Met等位基因携带者相比, 携带Val等位基因个体的酶活性更高, 细胞间隙多巴胺水平更低, 同时表现出较弱的前额叶神经元激活状态(Stein et al., 2006), 以及较弱的前额叶与杏仁核(在情绪的产生、识别和调节中起重要作用)功能连接(Klucken et al., 2015)。而前额叶功能弱化和杏仁核的过度激活与抑郁的发生存在显著关联(Rive et al., 2013; Matthews, Strigo, Simmons, Yang, & Paulus, 2008; 廖成菊, 冯正直, 2010)。

这是否意味着Val/Val基因型是易感基因型, 而Val/Met和Met/Met基因型是非易感基因型呢?通过回顾与梳理既有的相关文献, 我们发现, 在考察基因Val158Met多态性与环境对攻击行为交互作用的研究中, 大多数结果显示, Met等位基因表现出对环境更敏感的现象(Zhang, Cao, Wang, Ji, & Cao, 2016; Kim et al., 2008; 姜红燕等, 2005):譬如那些携带Met等位基因的青少年, 更易受母亲积极教养行为水平的影响而表现出更多或更少的反应性攻击行为(Zhang et al., 2016)。这提示我们基因的易感性可能并不是绝对的, 它应当是针对研究的结果变量而言的。当研究的结果变量不同时, 同一基因的易感基因型表现甚至是截然相反的。具体而言, 携带Val/Val基因型的个体可能更易受环境的影响而表现出更高或更低的抑郁水平, Met等位基因携带者则更容易受环境的影响而表现出较多或较少的攻击行为。因此, 我们在谈及易感基因时, 确切的表达或许应该是某种心理或行为特征的易感基因, 而不是简单地判定某基因为易感基因或非易感基因。另外, 还存在一种可能,基因Val158Met多态性对抑郁的易感性并非是“全或无”的, 而是Val/Val基因型比Val/Met和Met/Met基因型对抑郁更具有易感性:当环境变量的变异范围足够大时, 则可能发现携带不同基因型的个体都会对环境作出反应, 只不过反应的程度不同; 但当环境变量变异范围有限时, 往往只能发现Val/Val基因型具有易感性, 而其他基因型不具有。若将来我们能够获得更大变异范围的环境变量, 则很有可能发现Met等位基因(Val/Met和Met/Met基因型)也会表现出一定程度的易感性。

此外, 我们未发现负性生活事件、基因Val158Met多态性和父亲消极教养行为之间存在任何显著的交互作用, 即无论个体是Val/Val基因型还是携带Met等位基因, 或者父亲消极教养行为水平高低, 负性生活事件均可以显著正向预测青少年的抑郁水平。为什么同父亲积极教养行为相比, 父亲消极教养行为的调节作用没有达到显著性水平?我们推测可能是由于本研究的对象大多是处于正常家庭中的青少年, 父亲消极教养行为的得分和变异程度均低于父亲积极教养行为, 因此较低的父亲消极教养行为水平和变异削弱了负性生活事件影响和基因功能的表达机会。

需要指出的是, 在本研究中我们发现负性生活事件对抑郁的影响受到基因Val158Met多态性和父母教养行为的调节作用, 都仅表现在男青少年中。尽管目前该三者交互存在性别差异的神经生物机制尚不清楚, 但我们推测该现象可能与性激素有关。有研究表明性激素可能会调节抑郁相关基因的表达, 譬如女性雌激素通过抑制mRNA的表达来调节COMT活性(Chen et al., 2004)。另一方面性激素可能直接影响多巴胺系统的功能。虽然关于人类雌激素−多巴胺直接联系的研究较为匮乏, 但是有关药理学fMRI-PET的研究指出, 女性中的雌激素在多巴胺信号传导和额纹状体功能的调节中可能发挥着重要作用(Jacobs & D'Esposito, 2011; Pohjalainen, Rinne, Någren, Syvälahti, & Hietala, 1998)。

本研究是首篇同时考察负性生活事件、基因Val158Met多态性和父母教养行为对青少年早期抑郁交互作用机制的研究, 结果发现负性生活事件对抑郁的效应受到基因Val158Met多态性和父亲积极教养行为的调节, 且该调节作用只存在于男青少年群体中。在对显著性水平进行校正, 以及进行内部验证性分析和元分析检验后, 该结果依然稳定。这说明青少年早期抑郁的发生的确存在基因和多环境因素的复杂交互机制, 为青少年早期抑郁发生的理论建构及其干预提供了重要启示。此外, 本研究的局限是:(1)由于采用的是横向设计, 负性生活事件、基因Val158Met多态性和父母教养行为对青少年抑郁的影响是否存在年龄效应尚无法确定。因此在后续研究中, 可以采用纵向研究设计, 进一步探查基因Val158Met多态性与多环境因素对青少年抑郁影响的动态变化问题。(2)本研究的遗传指标仅采用了一个候选基因位点。与多基因设计研究相比, 其有限的解释力也是不可否认的, 甚至近期的一项研究(Border et al., 2019)指出, 科学界应该摒弃“候选基因假说”。其理由是:随机选择的基因, 以及18个以往被研究者高度重视的候选基因与重性抑郁在统计学上均无显著关联。但我们认为该研究在方法和逻辑上存在几个问题:一是该研究对性别的效应进行了控制。然而现有的诸多研究表明(Priess-Groben & Hyde, 2013; Nyman et al., 2011; Uddin et al., 2011), 基因与环境对抑郁的影响存在性别差异, 而且作用的方向可能是截然相反的。本研究的补充性分析也发现, 当我们忽略性别因素的影响时, 负性生活事件、基因Val158Met多态性和父亲积极教养行为对青少年抑郁的交互作用也变得不显著了。这说明将性别作为控制变量来揭示基因与环境对抑郁的效应是不合适的。二是作者在否定了“候选基因假说”后又指出重性抑郁并非不可遗传。既然抑郁是可遗传的, 那么该怎么研究遗传因素的影响呢, 作者并没有明确说明。如果不用候选基因策略的话, 很可能用全基因组测序技术。而全基因组测完序之后总会发现有的基因与抑郁相关, 有的不相关。对于那些被发现与抑郁显著关联的基因位点, 我们又该如何进一步分析其在抑郁发生中的作用呢?最终我们还会回归到候选基因策略, 只不过选出来的基因位点是“海选”出来的, 而不是基于文献或基因的生物功能等信息直接“推荐”出来的, 但本质上还是不能摒弃候选基因策略。第三, 将整体分解为部分进行探究, 历来是科学研究的主要方法之一。正如我们将人的心理分解为知、情、意、行去研究, 但并不意味着我们就认为这四个方面中的任何一个能决定人的心理一样, 我们采用候选基因的研究策略, 也并非意味着我们就认为抑郁只与其中的几个候选基因有关, 它只是考察基因对抑郁影响的一个不可或缺的途径。如果只是简单提出需要考察所有基因的效应, 在所有基因作用于抑郁的神经生物机理尚不清楚的现状下, 这样的提议是没有可操作性和现实价值的。因此, 目前单基因−环境设计研究依然具有其存在的独特价值, 特别是那些采用像基因Val158Met多态性这样的对前额区域中的多巴胺水平起关键调节作用的候选基因位点为遗传指标的研究。(3)本研究只进行了单次取样, 尽管内部验证的结果较为稳定, 但是未来仍需要在其他样本, 尤其是更大样本中进行外部验证。

Antypa, N., Drago, A., & Serretti, A. (2013). The role of COMT gene variants in depression: Bridging neuropsychological, behavioral and clinical phenotypes.(8), 1597−1610.

Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2011). Differential susceptibility to rearing environment depending on dopamine-related genes: New evidence and a meta-analysis.(1), 39–52.

Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing.(1), 289–300.

Bilsky, S. A., Cole, D. A., Dukewich, T. L., Martin, N. C., Sinclair, K. R., Tran, C. V., … Maxwell, M. A. (2013). Does supportive parenting mitigate the longitudinal effects of peer victimization on depressive thoughts and symptoms in children?(2), 406−419.

Border, R., Johnson, E. C., Evans, L. M., Smolen, A., Berley, N., Sullivan, P. F., … Keller, M. C. (2019). No support for historical candidate gene or candidate gene-by-interaction hypotheses for major depression across multiple large samples.(5), 376−387.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979).Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Burrill, D. (1998).The Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, Ontario.

Cao, C., Rijlaarsdam, J., van der Voort, A., Ji, L. Q., Zhang, W. X., & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. (2018). Associations between dopamine D2 receptor (DRD2) gene, maternal positive parenting and trajectories of depressive symptoms from early to mid-adolescence.(2), 365−379.

Cao, C., Wang, M. P., Cao, Y. M., Ji, L. Q., & Zhang, W. X. (2017). The interactive effects of monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) gene and peer victimization on depressive symptoms in early adolescent boys: The moderating role of catechol- O-methyltransferase (COMT) gene.(2), 206−218.

[曹丛, 王美萍, 曹衍淼, 纪林芹, 张文新. (2017). MAOA基因T941G多态性与同伴侵害对男青少年早期抑郁的交互作用:COMT基因Val158Met多态性的调节效应.(2), 206−218.]

Chen, J., Lipska, B. K., Halim, N., Ma, Q. D., Matsumoto, M., Melhem, S., … Weinberger, D. R. (2004). Functional analysis of genetic variation in catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT): Effects on mRNA, protein, and enzyme activity in postmortem human brain.(5), 807−821.

Chen, J., Li, X., & Mcgue, M. (2012). Interacting effect of BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and stressful life events on adolescent depression.(8), 958−965.

Comasco, E., Sylvén, S. M., Papadopoulos, F. C., Sundström-Poromaa, I., Oreland, L., & Skalkidou, A. (2011). Postpartum depression symptoms: A case-control study on monoaminergic functional polymorphisms and environmental stressors.(1), 19−28.

Domschke, K., Zavorotnyy, M., Diemer, J., Nitsche, S., Hohoff, C., Baune, B. T., … Zwanzger, P. (2010). COMT Val158Met influence on electroconvulsive therapy response in major depression.(1), 286−290.

Drury, S. S., Theall, K. P., Smyke, A.T., Keats, B. J., Egger, H. L., Nelson, C. A., … Zeanah, C. H. (2010). Modification of depression by COMT Val158Met polymorphism in children exposed to early severe psychosocial deprivation.(6), 387−395.

Evans, J., Xu, K., Heron, J., Enoch, M-A., Araya, R., Lewis, G., … Goldman, D. (2010). Emotional symptoms in children: the effect of maternal depression, life events, and COMT genotype.(2), 209−218.

Healy, K. L., & Sanders, M. R. (2018). Mechanisms through which supportive relationships with parents and peers mitigate victimization, depression and internalizing problems in children bullied by peers.(5), 800−813.

Hetolang, L. T, & Amone-P'Olak, K. (2018). The associations between stressful life events and depression among students in a university in Botswana.(2), 255−267.

Hosang, G. M., Fisher, H. L., Cohen-Woods, S., Mcguffin, P., & Farmer, A. E. (2017). Stressful life events and catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) gene in bipolar disorder.(5), 419−426.

Jacobs, E., & D'Esposito, M. (2011). Estrogen shapes dopamine-dependent cognitive processes: Implications for women’s health.(14), 5286−5293.

Jiang, H-Y., Xu, X-F., Zhao, X-D., Cheng, Y-Q., Liu, H., & Yang, J-Z. (2005). Association study between aggression behavior in schizophrenics and catechol-O-methyltransferase gene polymorphism.(3), 202−205.

[姜红燕, 许秀峰, 赵旭东, 程宇琪, 刘华, 杨建中. (2005). 精神分裂症攻击行为与儿茶酚氧位甲基转移酶基因多态性.(3), 202−205.]

Karoum, F., Chrapusta, S. J., & Egan, M. F. (1994). 3-Methoxytyramine is the major metabolite of released dopamine in the rat frontal cortex: Reassessment of the effects of antipsychotics on the dynamics of dopamine release and metabolism in the frontal cortex, nucleus accumbens, and striatum by a simple two pool model.(3), 972–979.

Kim, Y-R., Kim, J. H., Kim, S. J., Lee, D., & Minc, S. K. (2008). Catechol-methyltransferase Val158Met polymorphism in relation to aggressive schizophrenia in a Korean population.(11), 820−825.

Klucken, T., Kruse, O., Wehrum-Osinsky, S., Hennig, J., Schweckendiek, J., & Stark, R. (2015). Impact of COMT Val158Met polymorphism on appetitive conditioning and amygdala/prefrontal effective connectivity.(3), 1093−1101.

Lachman, H. M., Papolos, D. F., Saito, T., Yu, Y. M., Szumlanski, C. L., & Weinshilboum, R. M. (1996). Human catechol-O-methyltransferase pharmacogenetics: Description of a functional polymorphism and its potential application to neuropsychiatric disorders.(3), 243−250.

Liao, C-J., & Feng, Z-Z. (2010). Mechanism of affective and cognitive-control brain regions in depression.(2), 282−287.

[廖成菊, 冯正直. (2010). 抑郁症情绪加工与认知控制的脑机制.(2), 282−287.]

Matsumoto, M., Weickert, C. S., Akil, M., Lipska, B. K., Hyde, T. M., Herman, M. M., … Weinberger, D. R. (2003). Catechol-O-methyltransferase mRNA expression in human and rat brain: Evidence for a role in cortical neuronal function.(1), 127−137.

Matthews, S. C., Strigo, I. A., Simmons, A. N., Yang, T. T., & Paulus, M. P. (2008). Decreased functional coupling of the amygdala and supragenual cingulate is related to increased depression in unmedicated individuals with current major depressive disorder.(1), 13−20.

Natsuaki, M. N., Biehl, M. C., & Ge, X. J. (2010). Trajectories of depressed mood from early adolescence to young adulthood: The effects of pubertal timing and adolescent dating.(1), 47−74.

Nyman, E. S., Sulkava, S., Soronen, P., Miettunen, J., Loukola, A., Leppä, V., … Paunio, T. (2011). Interaction of early environment, gender and genes of monoamine neurotransmission in the aetiology of depression in a large population-based Finnish birth cohort.(1), e000087.

Pohjalainen, T., Rinne, J. O., Någren, K., Syvälahti, E., & Hietala, J. (1998). Sex differences in the striatal dopamine D2 receptor binding characteristics in vivo.(6), 768−773.

Priess-Groben, H. A., & Hyde, S. J. (2013). 5HTTLPRstress in adolescent depression: Moderation by MAOA and gender.(2), 281−294.

Rive, M. M., van Rooijen, G., Veltman, D. J., Phillips, M. L., Schene, A. H., & Ruhé, H. G. (2013). Neural correlates of dysfunctionasl emotion regulation in major depressive disorder. A systematic review of neuroimaging studies.(10), 2529–2553.

Roberts, Y. H., English, D., Thompson, R., & White, C. R. (2018). The impact of childhood stressful life events on health and behavior in at-risk youth., 117−126.

Rózycka, A., Słopień, R., Słopień, A., Dorszewska, J., Seremak-Mrozikiewicz, J., Lianeri, M., … Jagodziński, P. P. (2016). The MAOA, COMT, MTHFR and ESR1 gene polymorphisms are associated with the risk of depression in menopausal women., 42−54.

Stein, D. J., Newman, T. K., Savitz, J., & Ramesar, R. (2006). Warriors versus worriers: The role of COMT gene variants.(10), 745−748.

Stikkelbroek, Y., Bodden, D. H. M., Kleinjan, M., Reijnders, M., & van Baar, A. L. (2016). Adolescent depression and negative life events, the mediating role of cognitive emotion regulation.(8), e0161062.

Suzuki, M., Furihata, R., Konno, C., Kaneita, Y., Ohida, T., & Uchiyama, M. (2018). Stressful events and coping strategies associated with symptoms of depression: A Japanese general population survey., 482−488.

Tang, A-M., Deng, X-L., Du, X-X., & Wang, M-Z. (2018). Harsh parenting and adolescent depression: Mediation by negative self-cognition and moderation by peer acceptance.(1), 22−37.

Timmermans, M., van Lier, P. A. C., & Koot, H. M. (2010). The role of stressful events in the development of behavioural and emotional problems from early childhood to late adolescence.(10), 1659−1668.

Tucker, C. J., Sharp, E. H., van Gundy, K. T., & Rebellon, C. (2018). Household chaos, hostile parenting, and adolescents’ well-being two years later.(11), 3701−3708.

Uddin, M., de los Santos, R., Bakshis, E., Cheng, C., & Aiello, A. E. (2011). Building conditions, 5-HTTLPR genotype, and depressive symptoms in adolescent males and females.(4), 379−385.

Vai, B., Riberto, M., Poletti, S., Bollettini, I., Lorenzi, C., Colombo, C., & Benedetti, F.(2017). Catechol-o- methyltransferase Val (108/158) Met polymorphism affects fronto-limbic connectivity during emotional processing in bipolar disorder., 53−59.

Wang, M. P., Zhang, W. X., & Chen, X. Y. (2015). The Interaction between rs6295 Polymorphism in the 5-HTR1A Gene and parenting behavior on early adolescents’ depression: The verification of differential susceptability model.(5), 600–610.

[王美萍, 张文新, 陈欣银. (2015). 5-HTR1A基因rs6295多态性与父母教养行为对青少年早期抑郁的交互作用:不同易感性模型的验证.(5), 600−610.]

Wang, M. P., & Zhang, W. X. (2014). Association between COMT Gene rs6267 Polymorphism and Parent-Adolescent Cohesion and Conflict: The Analyses of the Moderating Effects of Gender and Parenting Behavior.(7), 931–941.

[王美萍, 张文新. (2014). COMT基因rs6267多态性与青少年期亲子亲合与冲突的关系:性别与父母教养行为的调节作用分析.(7), 931−941.]

Wang, X. D. (1999).Peking, China: Chinese Mental Health Journal Press.

[汪向东. (1999).北京: 中国心理卫生杂志社, 106−108.]

Zhang, W. X., Cao, C., Wang, M. P., Ji, L. Q., & Cao, Y. M. (2016). Monoamine oxidase a (MAOA) and catechol-O- methyltransferase (COMT) gene polymorphisms interact with maternal parenting in association with adolescent reactive aggression but not proactive aggression: Evidence of differential susceptibility.(4), 812−829.

Zhang, W. X., Cao, Y. M., Wang, M. P., Ji, L. Q., Chen, L., & Deater-Deckard, K. (2015). The dopamine D2 receptor polymorphism (DRD2 TaqIA) interacts with maternal parenting in predicting early adolescent depressive symptoms: Evidence of differential susceptibility and age differences.(7), 1428−1440.

Association between negative life events and early adolescents’ depression: The moderating effects of Catechol-O-methyltransferase () Gene Val158Met polymorphism and parenting behavior

WANG Meiping; ZHENG Xiaojie; XIA Guizhi; LIU Didi; CHEN Pian; ZHANG Wenxin

(School of Psychology, Shandong Normal University, Jinan 250358, China)

Early adolescence is a critical period for examining the development of depression in that there is a sharp increase in the prevalence. Existing studies suggested that depression was significantly associated with negative life events. However, it is well-known that not all adolescents who experienced negative life events would become depressed. Findings from molecular genetics indicated that catechol-O-methyltransferase () gene Val158Met polymorphism might be an important candidate gene of depression. Some researches have also investigated the moderating effect ofgene Val158Met polymorphism on the association between negative life events and depression. However, the findings still remain inconsistent. According to developmental system theory, family factors, such as parental rearing behavior, may also play an important role on adolescent depression. However, whether and howgene Val158Met polymorphism with parenting behavior moderate the association between negative life events and early adolescent depression remain unclear. Moreover, extant evidence has demonstrated that there is a significant gender difference in the interaction between gene and environment on depression. The aim of this study was to investigate the moderating role ofgene Val158Met polymorphism and parenting behavior on the association between negative life events and early adolescent depression, and its possible gender differences.

In this study, 637 adolescents (= 13.50 years, male = 344) of two middle schools in Jinan were selected as subjects. Adolescent depressive symptoms, negative life events and parenting behavior were accessed using self-rated children’s depression inventory (CDI), adolescent life events scale and parental rearing behavior questionnaire. All measures showed good reliability. DNA was extracted from saliva. Genotype at Val158Met polymorphism was performed for each participant with MassARRAY RT software version 3.0.0.4 and analyzed using the MassARRAY Typer software version 3.4 (Sequenom). A series of hierarchical regressions, internal replication analyses and meta-analyses were conducted to examine the effects of negative life events, Val158Met polymorphism and parenting behavior on adolescent depression.

The results showed that negative life events significantly positively predicted early adolescent depression. Moreover, negative life events,gene Val158Met polymorphism and positive paternal behavior had a significant three-way interaction on adolescent depression, which only existed in male adolescents. Specifically, for male adolescents with Val/Val genotype, positive paternal behavior played a significant moderating effect on the association between negative life events and depression. When the level of positive paternal behavior was lower, negative life events could positively predict male adolescent depression, whereas its effect was not significant when the level of positive paternal behavior was higher. Additionally, the above mentioned interaction was not observed among male adolescents with Met allele. The findings also indicated that both positive and negative maternal behaviors had marginally significant interactions withgene Val158Met polymorphism and negative life events, and were also manifested only in male adolescents. In the further simple effect analysis of the three-way interactions, male adolescents with Val/Val genotype were still more sensitive to the environment.

Overall, our results suggested that the effects of negative life events on early adolescent depression were moderated bygene Val158Met polymorphism and parenting behavior, and there were gender differences in the moderating effect. More importantly, this study emphasizes the effects of genes and multiple environments on depression, which lends a reference for future studies on the interaction between genes and multiple environments. Besides, the findings provide important implications for the theoretical construction and intervention of adolescent depression.

negative life events; depression; COMT gene Val158Met polymorphism; parenting behavior; gender difference

2019-01-21

* 国家自然科学基金青年项目(31500899)、国家自然科学基金面上项目(31671156)。

B844; B845

王美萍, E-mail: wangmeiping@sdnu.edu.cn