Role of macrophages in peripheral nerve injury and repair

Ping Liu , Jiang Peng, Gong-Hai Han, Xiao Ding, Shuai Wei, Gang Gao, Kun Huang, Feng Chang, , Yu Wang,

1 Shanxi Medical University, Taiyuan, Shanxi Province, China

2 Institute of Orthopedics, Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing, China

3 Kunming Medical University, Kunming, Yunnan Province, China

4 Shihezi University Medical College, Shihezi, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China

5 Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Shanxi Provincial People's Hospital, Shanxi Medical University, Taiyuan, Shanxi Province, China

6 Anhui Medical University Air Force Clinical College, Hefei, Anhui Province, China

Abstract Resident and inflammatory macrophages are essential effectors of the innate immune system. These cells provide innate immune defenses and regulate tissue and organ homeostasis. In addition to their roles in diseases such as cancer, obesity and osteoarthritis, they play vital roles in tissue repair and disease rehabilitation. Macrophages and other inflammatory cells are recruited to tissue injury sites where they promote changes in the microenvironment. Among the inflammatory cell types, only macrophages have both pro-inflammatory (M1) and anti-inflammatory (M2) actions, and M2 macrophages have four subtypes.The co-action of M1 and M2 subtypes can create a favorable microenvironment, releasing cytokines for damaged tissue repair. In this review, we discuss the activation of macrophages and their roles in severe peripheral nerve injury. We also describe the therapeutic potential of macrophages in nerve tissue engineering treatment and highlight approaches for enhancing M2 cell-mediated nerve repair and regeneration.

Key Words: nerve regeneration; macrophage; origin; polarization; function; nerve injury; nerve repair; tissue engineering; neural regeneration

Introduction

Macrophages have the powerful ability to phagocytize foreign bodies (Wynn et al., 2013). They are found in all tissues, where they act as sentinels that protect the tissue and ensure organ homeostasis. Tissue-specific macrophage types originate during development and include osteoclasts(bone), alveolar macrophages (lung), histiocytes (interstitial connective tissue), Kupffer cells (liver and gut), splenic macrophages (spleen), microglia (brain) and differentiated Schwann cells (peripheral nervous system) (Chen et al.,2015). Macrophages function as phagocytic antigen-presenting cells and have key roles in scavenging heterologous pathogens and transmitting danger signals; they are also involved in the formation of memory cells (Iijima and Iwasaki, 2014). However, they may also contribute to secondary infections (Gaya et al., 2015) and cancer metastasis(Keklikoglou and De Palma, 2014). Because of their roles in tissue repair, macrophages represent viable targets for disease treatment (Suzuki et al., 2014; Sadtler et al., 2016).A study by Suzuki et al. (2014) has indicated the potential therapeutic use of pulmonary macrophage transplantation for the treatment of hereditary pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. The application of macrophage-based therapies against peripheral nerve injury is attractive because the proximal and distal ends of the peripheral nerve participate in completely distinct events: proximal regeneration and distal denaturation (DeFrancesco-Lisowitz et al., 2015).Macrophages involved in distal degeneration promote the switch from the pro-inflammatory (M1) to the anti-inflammatory (M2) phenotype, which enhances proximal nerve regeneration (Mokarram et al., 2012). In the M2 macrophage subtypes, in addition to their common anti-inflammatory effects, they also have their respective functions.Briefly, M2a, M2b, M2c and M2d macrophages promote cell proliferation, cell maturation, resolution of inflammation and angiogenesis, respectively (Ferrante and Leibovich,2012; Novak and Koh, 2013a, b; Chen et al., 2015; Gensel and Zhang, 2015). The M2 macrophage subtypes have great therapeutic potential given their documented anti-inflammatory effects and their respective functions in promoting tissue regeneration in engineered nerve tissue models(Mokarram et al., 2012).

In this review, we discuss the origin, polarization, type and function of macrophages, highlight their roles in peripheral nerve injury and describe their therapeutic value in neural tissue engineering.

We performed a literature search in PubMed from 2002 to December 2018 of studies published in English. The key words were macrophages [MeSH Terms], macrophage polarization and function, and peripheral nerve injuries [MeSH Terms]. The results were further screened by title/abstract,and non-Scientific Citation Index experiments and review articles. Furthermore, studies concerning central nervous system diseases and neoplasms were excluded.

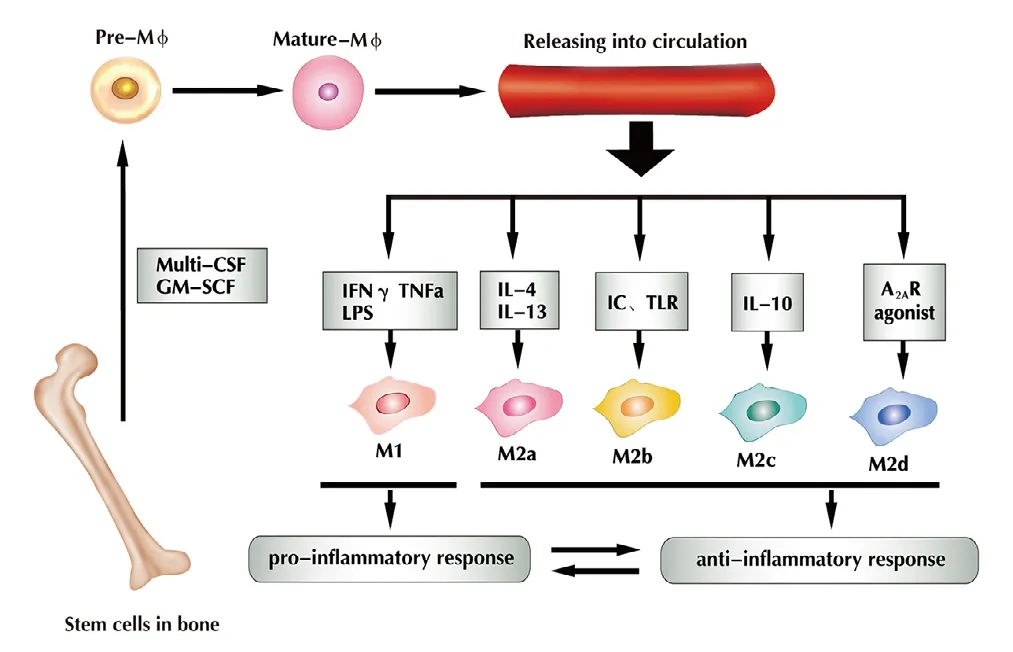

Origin, Polarization, and Function of Macrophages

Tissue-resident macrophages and circulating macrophages(Geissmann et al., 2010; Davies and Taylor, 2015) originate from bone marrow hematopoietic stem cells (Wynn et al.,2013) (Figure 1). Before circulating macrophages enter the bloodstream, they must be stimulated by cytokines such as multi-colony stimulating factor (multi-CSF) and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (Wu et al.,2017). Upon stimulation, these cells develop into monocytes,and then differentiate further into pre-macrophages. Finally,they become mature macrophages and are released into the circulation (Chen et al., 2015; Helft et al., 2015).

The macrophage polarization process transforms the macrophages' functions according to their current environment(Li et al., 2018). M1 macrophages are pro-inflammatory that secrete cytokines. M2 macrophages are anti-inflammatory macrophages that promote tissue repair. Because of this dual function, macrophages serve as potent immune effector cells. They play important roles in tissue homeostasis and disease rehabilitation, e.g., promoting the initiation and progression of tissue injury, as well as promoting wound healing and tissue remodeling. Macrophages show different functions at different disease stages; therefore their proper induction and elimination are necessary for efficient recovery (Duffield et al., 2005; Mantovani and Locati, 2013; Zhou et al., 2014). Heterogeneity and plasticity are hallmarks of macrophages (Gordon and Plűddemann, 2013; London et al., 2013) (Table 1). A variety of stimuli can induce different degrees of phenotypic polarization. In general, macrophage activation is classified as classic activation (M1) and selective activation (M2). M1 macrophages are induced by Tolllike receptor (TLR), ligands and interferon (IFN)-γ, and express CD32, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2),CD86, inducible nitric oxide synthase, HLA-DR, CD197,hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), IFN regulatory factor 1, myeloid differentiation primary response 88, TLR-2 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (Mueller and Schultze-Mosgau, 2011; Gensel and Zhang, 2015; Bardi et al., 2018). Polarized M1 macrophages mainly secrete pro-inflammatory factors, which aggravate inflammation and promote debris removal, sterilization and elimination of apoptotic cells (Gensel and Zhang, 2015).Compared with M1 macrophages, the activation pathway of M2 macrophages is complex. MS-275, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, induces the transformation of M1 to M2 type macrophages (Zhang and Schluesener, 2012). Additional studies have indicated that M2 macrophages can be induced by interleukin (IL)-4/IL-13 (M2a) to express insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), IL1RN and CD206. M2a macrophages promote anti-inflammatory effects such as cell proliferation and migration, production of growth factors and removal of apoptotic cells. M2b macrophages are induced by an immune complex and express CD86, TNFα, CD64,vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and IGF-1. M2b macrophages promote cell maturation, tissue stabilization,angiogenesis and extracellular matrix synthesis. M2c macrophages are induced by the anti-inflammatory cytokines,IL-10 and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), expressing SLAM, Sphk-1, THBS1, HMOX-1, TGF-β, CD206 and CD163. They accelerate the resolution of inflammation,tissue repair and extracellular matrix synthesis, and produce growth factors. M2d macrophages are induced by the A2AR agonist and express high levels of VEGF, IL-10 and inducible nitric oxide synthase, and low levels of TNFα, IL-12 and arginase-1 (Gordon, 2003; Biswas and Mantovani,2010; Fujiu et al., 2011; Ferrante et al., 2013; Sudduth et al.,2013; Chen et al., 2015). M2d macrophages derived from M1 macrophages have roles in angiogenesis and wound healing (Ferrante and Leibovich, 2012; Chen et al., 2015;Gensel and Zhang, 2015). With changes in the environment,M1 and M2 macrophages maintain a state of dynamic equilibrium. The dynamic switching of phenotype and function in macrophages is regulated by modulating signals (Jang et al., 2013; Mercalli et al., 2013). Recent studies have reported that M2 macrophages could also differentiate into M1 macrophages upon stimulation with lactoferrin-containing immune complexes, thus emphasizing their dynamic nature(Gao et al., 2018).

Recruitment of Macrophages to Injury Sites

The processes of macrophage recruitment and polarization are necessary for macrophage-mediated injury repair(Kucharova and Stallcup, 2018). Recruitment requires the help of chemokines or other signaling proteins. For example,AMPKa1 serves as a recruitment signal in the regeneration of skeletal muscle. In the absence of AMPKa1, macrophages do not acquire the M2 phenotype and have impaired phagocytosis (Lawrence and Fong, 2010). The CC chemokine,CCL2, and its receptor, CCR2, are responsible for monocyte trafficking in response to bone fractures (Xing et al., 2010).Mice deficient in CCR suffer from osteosclerosis (Binder et al., 2009). As a consequence, macrophage recruitment to the site of injury is necessary. After a peripheral nerve injury,monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1, also called CCL2), leukemia inhibitory factor, IL-1α, IL-1β and pancreatitis-associated protein III serve as the major monocyte/macrophage recruitment signals (Shamash et al., 2002; Tofaris et al., 2002; Namikawa et al., 2006; Van Steenwinckel et al., 2015). Macrophage infiltration is first observed at the site of injury 2-3 days post-injury and peaks at 7 days post-injury (Perry et al., 1987; Taskinen and Röyttä, 1997; Bendszus and Stoll, 2003; Mueller et al., 2003; Namikawa et al., 2006).To boost recruitment, infiltrated macrophages may secrete CCL2, TNFα, IL-1α and IL-1β (Shamash et al., 2002; Kiguchi et al., 2013). In nerve injury models, macrophage recruitment occurs even in the absence of the key recruitment signals, MCP-1 and IL-1β, as injured nerves also produce recruitment signals (Shamash et al., 2002). In Schwann cells,macrophage recruitment is regulated by the miR-327/CCL2 axis. When stimulated by the outside microenvironment,the increase in miR-327 expression inhibits macrophage recruitment, while CCL2 promotes macrophage recruitment(Zhao et al., 2017). In CCR2-deficient mice, macrophage infiltration to injured nerve sites is significantly decreased(Siebert et al., 2000; DeFrancesco-Lisowitz et al., 2015),which indicates that CCL2 is a primary pro-recruitment molecule. In summary, cytokine signaling is necessary for proper macrophage recruitment and subsequent injury repair.

After recruitment, the number of macrophages in the injured site increases. The macrophage subtypes do not increase simultaneously. Previous studies have indicated that macrophages, in most tissues, transit from M1 to M2 macrophages over time (Arnold et al., 2007; Dal-Secco et al., 2015). In addition to the above-mentioned polarization stimulation factors derived from injury, the M2a subtype can secret cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β, polarizing macrophages toward the M2c subtype directly (David and Kroner, 2011). When recruited and polarized, macrophages secrete cytokines to prepare for tissue repair.

Roles of Macrophages in Peripheral Nerve Injury

Figure 1 Under the regulation of cytokines (multi-CSF andGM-SCF), bone marrow-derived macrophages differentiate intomononuclear cells, and then gradually become mature macrophages that can be released into the circulation.IFN-γ, TNFα and LPS stimulate macrophages into M1, IL-4 and IL-13 into M2a, IC and TLR into M2b, and IL-10 into M2c; A2AR agonist stimulates them into M2d. M1 macrophages induce a pro-inflammatory response, whereas M2 macrophages induce an anti-inflammatory response, and both exist in dynamic equilibrium (Chen et al., 2015).Multi-CSF: Multi-colony stimulating factor; GM-CSF: granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor; IFN-γ: interferon gamma;TNFα: tumor necrosis factor alpha; LPS: lipopolysaccharides; IC:immune complexes; TLR: toll-like receptor; A2AR: adenosine A2A receptor; IL: interleukin; IL-1R: IL-1 receptor. Adapted from Chen et al.(2015) and Helft et al. (2015).

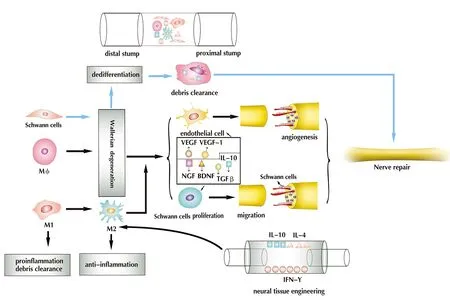

Nerve injury includes central nerve injury and peripheral nerve injury, both of which present challenges with respect to clinical treatment and functional recovery (Burtt et al.,2017), particularly those associated with the spinal cord.By contrast, skin and muscle tissues respond well to tissue repair mechanisms and show good recovery. The mechanisms governing these tissue-specific differences are not well understood, but it is clear that macrophages are key mediators of repair in all tissue types. Spinal cord injury can induce a chronic wound state that undergoes expansion and maintains demyelination, leading to impaired recovery and progressive tissue degeneration (Chiu et al., 2018). A spinal cord injury consists of three phases: inflammation, proliferation and remodeling (Gensel and Zhang, 2015). The central nervous system is unique in that complete regeneration after injury is rare, and relative to other injury forms, the repair process is complex and poorly understood. By contrast, peripheral nerves have strong regenerative capacity and macrophages play a core role in their repair. Injuries will induce distal segment of the nerve undergoing a series of cellular and molecular events that result in breakdown of the distal nerve segment, which is called Wallerian degeneration (Rotshenker, 2011), thereby promoting the regeneration of peripheral nerve. For these reasons, we will focus primarily on macrophage-mediated repair in the peripheral nerve injury setting. Unlike the central nervous system, where damagedneurons are usually unable to regenerate, axons in the peripheral nervous system can regenerate after injury (Figure 2).

Table 1 Characteristics of macrophages

After nerve injuries, especially severe and long-distance nerve injuries, local hypoxia and tissue necrosis secondary to inflammation are major obstacles for nerve repair and regeneration, which require a good microenvironment that is clean of necrotic tissue fragments, to promote angiogenesis,and the proliferation and migration of glial cells (Schwann cells). However, macrophages have the capacity to promote nerve repair (Cattin et al., 2015).

Macrophages respond to hypoxia by promoting angiogenesis

Damage to peripheral nerves promotes the recruitment and infiltration of many inflammatory cell types. Among the inflammatory cell types, only macrophages can sense (Cattin et al., 2015) and respond to hypoxic conditions through activation of the transcription factor, HIF-1α, which ultimately stimulates angiogenesis via VEGF activation (Pugh and Ratcliffe, 2003; Krock et al., 2011). In this case, macrophages in both the distal and proximal stumps are in hypoxic conditions (pO2< 10 mmHg) (Young and Moller, 2010). At 2 days post-injury and before vascularization, a large number of hypoxic cells are present at the site of injury. This triggers HIF-1α synthesis in macrophages, followed by the expression of VEGF-A, which stimulates endothelial cell proliferation and migration. By day 3 post-injury, the proportion of hypoxic cells is substantially decreased, which indicates vascularization of the injured site (Cattin et al., 2015). Macrophages promote angiogenesis (Fantin et al., 2010) and maintain the health of endothelial cells by secreting VEGF-A(Lee et al., 2007). Macrophage-induced angiogenesis, which provides nutrition for the repair of the nerve tissue, is a critical step in injury repair. In addition, as macrophages are polarized into different subtypes, they can release cytokines to accelerate angiogenesis. For example, M2d macrophages secrete IL-10 and VEGF, which facilitate angiogenesis and the repair of blood vessels (Ferrante and Leibovich, 2012).Furthermore, angiogenesis provides a route for the migration of Schwann cells to the injury site.

Macrophages contribute to the migration and proliferation of Schwann cells

Macrophages promote inflammation through the production and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. In addition, they serve as important antigen-presenting cells,stimulating an immune response to repair damage and accelerate recovery (Mueller et al., 2003). In addition to these roles, macrophages activate the proliferation and division of Schwann cells, which are vital glial cells in the peripheral nerve tissue (Armstrong et al., 2003). A previous study has indicated that after injury, Wallerian denaturation in the distal stump nerve occurs, and Schwann cells begin to dedifferentiate into Schwann cell precursors (Chen et al., 2015). After dedifferentiation, progenitor Schwann cells have a stronger phagocytosis and secretory capacity.These features aid in debris removal from the injury site and increase the release of nerve growth factor (NGF),brain-derived growth factor and ciliary nerve growth factor,which are key growth factors involved in nerve repair, or regeneration and proliferation of Schwann cells (Gong et al., 2014; Hoyng et al., 2014). Wallerian denaturation is also associated with axonal degeneration, compromise of the blood-nerve barrier, myelin breakdown and macrophage infiltration (Stoll and Muller, 1999). Therefore, it effectively promotes macrophage infiltration, which subsequently promotes migration and proliferation of Schwann cells.Additional studies have reported that M2a macrophages boost cell proliferation and cell migration by releasing IL-10 or TGF-β (Ferrante and Leibovich, 2012; Chen et al.,2015; Gensel and Zhang, 2015). In the hypoxic nerve injury microenvironment, macrophages sense low oxygen levels and promote angiogenesis, which allows endothelial cells to guide the direction of Schwann cell migration. Schwann cells use the polarized vasculature as a support to accelerate nerve repair and regeneration (Cattin et al., 2015), and synthesize the basement membrane for axon regeneration(Gong et al., 2014). Therefore, the macrophage-mediated migration and proliferation of Schwann cells has important implications in peripheral nervous system injuries.

Macrophages promote anti-inflammation and display enhanced scavenger function

In response to injury, macrophages are polarized into different subtypes to participate in damage repair. After activation, M1 macrophages show enhanced phagocytic ability along with increased scavenging of cellular debris and bacteria via upregulation of the scavenger receptor, CD36 (Sindrilaru and Scharffetter-Kochanek, 2013). M2a, M2b and M2c macrophages release anti-inflammatory cytokines, and increase cell proliferation and migration, tissue remodeling(via release of Arginase and Ym1) and secretion of growth factors (Novak and Koh, 2013a, b). Therefore, when macrophages retain the M1 state, injured nerve tissues remain in an inflammatory and chronic wound state (Wang et al.,2007; Hu et al., 2011; Sindrilaru et al., 2011; Rigamonti et al.,2014). In addition, it has been reported that macrophages modulate the expression of galectin-1 (Gaudet et al., 2015),which has been implicated in the regulation of phagocytosis,inflammation/gliosis and axon growth after spinal cord injury. Moreover, galectin-1 has been shown to promote neural stem cell proliferation (Sakaguchi et al., 2006; Yamane et al.,2010).

Macrophages Application in Neural Tissue Engineering

Self-repair is not an option when faced with severe and long-distance nerve injuries. Fortunately, significant technological progress has been made in the field of neural tissue engineering. Typical engineered nerve tissue includes a nerve scaffold, seed cells and nerve factors (Gu et al., 2014).The nerve scaffold provides support and protection, and the seed cells and related nerve factors accelerate nerve regeneration. Tissue engineering has become particularly applicable for the treatment of severe peripheral nerve damage. Although great progress has been made in nerve tissue engineering for long-distance nerve defects, improvements to optimize nerve regeneration and function restoration in target organs are still needed. Engineering involves the fabrication of a biocompatible artificial nerve scaffold that mimics the natural extracellular matrix (Gu et al., 2014),and the addition of seed cells and related factors to the nerve scaffold to promote nerve regeneration. Often, stem cells are selected as seed cells for nerve tissue engineering. Stem cells have the potential to differentiate into Schwann cells, secrete neurotrophic factors, and assist in nerve regeneration and myelin formation (Ren et al., 2012), but they cannot regulate inflammation or clean up necrotic debris (Mokarram et al.,2012). Therefore, efforts to incorporate macrophages into the engineered nerve tissue are of great importance.

Artificial nerve conduits can be used to bridge the ends of damaged peripheral nerves. Macrophages are recruited to the lesion under the action of chemokines (Shamash et al., 2002; Tofaris et al., 2002; Namikawa et al., 2006; Van Steenwinckel et al., 2015). Recruitment to the injury site leads to activation of both the M1 and M2 subtypes. The coordination of M1 and M2 regulates the initial events of local inflammation (Mokarram et al., 2012). The distal segment of the nerve undergoes a series of cellular and molecular events that result in Wallerian degeneration (Rotshenker, 2011).During this process, cytokine production contributes to the recruitment of inflammatory cells such as M1 cells (Chen et al., 2007). M1 cells release additional pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα, IL-1α and IL-1β, nitric oxide, reactive oxygen species and metalloproteinases (Murray and Wynn,2011), which promote further tissue destruction. To control this process, activated M2 macrophages release the anti-inflammatory cytokines, IL-4/IL-13 and IL-10, which mediate tissue restoration and suppression of pro-inflammatory responses (Gordon, 2003). Therefore, engineered nerve tissues would benefit from the incorporation of macrophages, given their key roles in the regulation of inflammation (Mokarram et al., 2012). The ratio of pro-healing (M2) to pro-inflammatory (M1) macrophages directly correlates with the number of regenerated axons (Mokarram et al., 2012). Thus, methods that increase the ratio of M2/M1 subtypes and promote nerve regeneration have become increasingly popular. There are two ways to increase the M2/M1 ratio in nerve injury or artificial nerve conduits. The first method incorporates the chemotaxis and polarization of macrophages by cytokines,and the second method involves direct injection of M2 into the nerve conduit. For the former approach, physical methods have been used to adsorb macrophage chemotactic factors onto nerve conduits. However, the physically adsorbed components are free to diffuse from the scaffold surface into the surrounding tissue shortly after implantation. Therefore,the chance of recruiting and polarizing macrophages to the M2 state is small (Wang et al., 2012). To address this challenge, a combination of conjugated and adsorbed IL-10 was found to be an effective approach for inducing macrophage M2 polarization in the vicinity of scaffolds (Potas et al.,2015). IL-10 desorbed from the scaffold is free to promote the polarization of macrophages beyond the scaffold surface.Macrophage stimulation by exogenous IL-10 subsequently triggers the production of endogenous IL-10 (Mantovani et al., 2002), which is significantly increased in M2 macrophages. It is commonly thought that M2 macrophages respond after M1 macrophages have fulfilled their roles. However, the presence of M2 macrophages at early time points post-injury indicates that M2 cell activation is promoted by extrinsic factors. M2 macrophages not only overcome axonal growth inhibition, but also promote regeneration (Kigerl et al., 2009). Further studies have shown that engineered scaffolds treated with IL-4 or IFN-γ directly polarized macrophages toward the M2a subtype, and indirectly toward the M2c subtype. M2a macrophages secrete cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β (David and Kroner, 2011), and function in cell proliferation and migration, removal of apoptotic cells,cell maturation, tissue stabilization, angiogenesis, resolution of inflammation and tissue regeneration (Ferrante and Leibovich, 2012; Chen et al., 2015; Gensel and Zhang, 2015).These results indicate that adsorption of cytokines on the scaffolds increases the ratio of M2 macrophages, leading to significantly enhanced nerve regeneration. The explanation for this observation is associated with the vital functions of macrophages in wound healing. Specifically, the optimal balance of macrophage types promotes healing by regulation of the injury microenvironment, detection of hypoxia,induction of angiogenesis (Cattin et al., 2015; Moore et al.,2018) and preparation of the surrounding parenchyma for regeneration.

The second method for enhancing the local M2 macrophage population involves direct injection of macrophages into the injured nerve or nerve conduit. This method was validated by a recent study that incorporated a model of ischemia developed by unilateral femoral artery excision.Macrophages (M0, M1, M2) and phosphate-buffered saline were injected into the ischemic muscle 24 h after injury.Four days after treatment, M1 macrophage therapy restored perfusion and the number of endothelial cells, improved muscle morphology and fibrosis, and promoted functional recovery (Lu et al., 2011). The transplantation of M1 macrophages promoted a faster transition from the M1-like to M2-like phenotype (Gensel and Zhang, 2015). Although this application cannot be used to promote nerve tissue repair or regeneration, the results indicate that during damage repair no single macrophage subtype can effectively promote the repair of damaged tissue.

Conclusion and Perspective

Macrophages are key mediators of inflammation. Macrophage recruitment to the site of injury initiates a cascade of events that contribute to proper nerve tissue repair. Macrophages not only play an important role in the repair of damaged nerves, but also represent a therapeutic target for treatment of peripheral nerve injury. Owing to their proand anti-inflammatory nature, macrophages are able to protect tissues and promote repair. During tissue repair, M1 macrophages secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines, thereby enhancing inflammatory reactions and tissue necrosis. By contrast, M2 macrophages induce an anti-inflammatory response, accelerate tissue repair and represent a target for therapeutic treatment. Effective tissue repair requires coordination of M1 and M2 activities. M1 macrophages have powerful phagocytic effects and promote a suitable microenvironment for M2 macrophages to repair the injured tissue.Interventions that involve injection of M1 macrophages into the sites of injury appear to have the best therapeutic effects.The injected M1 cells accelerated both the removal of necrotic tissue and transformation of the M1 to M2 phenotype.While promising, these outcomes have only been demonstrated in a model of ischemic muscle injury, and have not been observed in the context of peripheral nerve injury.In some immune system diseases, M2 polarization is suppressed and the number of M1 macrophages is increased,leading to increased inflammation and the improper repair of the injured tissues.

Figure 2 Injury alters the peripheral nerve microenvironment.Peripheral nerve damage promotes Wallerian degeneration, axonal degeneration, BNB compromise, myelin breakdown and macrophage infiltration. In Wallerian degeneration,Schwann cells undergo dedifferentiation, and along with macrophages, participate in the clearance of debris. Macrophages promote Wallerian degeneration, detect ischemia and promote angiogenesis by releasing VEGF and VEGF-1, all of which serve to promote the migration and proliferation of Schwann cells by releasing IL-10, TGF-β, NGF and BDNF,and working as a scavenger, while maintaining an M1/M2 dynamic balance. In neural tissue engineering, the adsorption of cytokines on the nerve scaffold (e.g., IL-10, IL-4, IFN-γ)increases the ratio of M2 macrophages, thereby promoting nerve regeneration. VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor; TGF-β: transforming growth factor-β; NGF: nerve growth factor; BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; IL: interleukin; IFN-γ: interferon-γ; BNB:blood-nerve barrier. Adapted from Cattin et al. (2015) and Chen et al. (2015).

Because the underlying mechanisms governing this process are poorly understood, further studies in this area are required for the successful development of novel therapeutic strategies.For example, a clear understanding of the specific therapeutic targets of macrophages is critical for the development of effective treatment strategies that involve macrophage activation.There is also uncertainty regarding the best methods for ascertaining what types of stimuli effectively promote macrophage M2 polarization. To be considered valuable for clinical applications, it is important to elucidate the regulatory mechanisms that control the transformation of macrophages to M2, and promote nerve repair and regeneration.

These findings shed light on improving peripheral nerve regeneration after scaffold modification by adsorption of cytokines such as IL-4, IFN-γ or IL-10, to promote macrophage M2 polarization. However, to promote nerve regeneration in neural tissue engineering, we need a good microenvironment, as well as good seed cells and nerve regeneration-related growth factors. Adsorption of M1 and M2 macrophage chemokines on scaffolds, or addition of polarized M1, and M1 macrophages as seed cells, may provide novel therapeutic targets for severe and long-distance nerve injuries. However, the amount and proportion of the two kinds of chemokines adsorbed on the scaffolds, and of polarized M1 and M2 macrophages added to the scaffolds need further study. The macrophage subtypes that respond to hypoxia, and promote the migration and proliferation of Schwann cells, and the mechanism remain to be further studied.

Author contributions:Literature search: PL; paper writing: JP, YW,FC; paper revision: GHH, XD, SW, GG, KH. All authors approved the final version of the paper.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no competing interests.

Financial support:This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 31771052 (to YW); the National Key Research & Development Program of China, No. 2017YFA0104701,2017YFA0104702 and 2016YFC1101601; the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program), No. 2014CB542201 (to JP); the Natural Science Foundation of Beijing, No. 7172202 (to YW); and the PLA Youth Training Project for Medical Science, No. 16QNP144 (to YW).None of the funding bodies plays any role in the study other than to provide funding.

Copyright license agreement:The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by all authors before publication.

Plagiarism check:Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review: Externally peer reviewed.

Open access statement: This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix,tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Open peer reviewers:Ozgur Boyraz, Gulhane Military Medical Academy, Turkey; Sheng Yi, Nantong University, China; Mark A. Yorek, University of Iowa, USA.

Additional files:Open peer review reports 1-3.

- 中国神经再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- Improvement of ataxia in a patient with cerebellar infarction by recovery of injured cortico-ponto-cerebellar tract and dentato-rubro-thalamic tract: a diffusion tensor tractography study

- Tandem pore TWIK-related potassium channels and neuroprotection

- Dendritic shrinkage after injury: a cellular killer or a necessity for axonal regeneration?

- Regenerative biomarkers for Duchenne muscular dystrophy

- Exploring the efficacy of natural products in alleviating Alzheimer's disease

- Therapeutic strategies for peripheral nerve injury:decellularized nerve conduits and Schwann cell transplantation