Recurrent renal cell carcinoma leading to a misdiagnosis of polycystic liver disease: A case report

Chen Liang, Kazuhiro Takahashi, Masanao Kurata, Shingo Sakashita, Tatsuya Oda, Nobuhiro Ohkohchi

Abstrac t BACKGROUND Polycystic liver disease (PCLD) with a large cystic volume deteriorates the quality of life of patients through substantial effects on the adjacent organs,recurrent cyst infections, cyst rupture, and hemorrhage. Surgical or radiological intervention is usually needed to alleviate these symptoms. We report a rare case of the cystic metastasis of renal cell carcinoma (RCC), which was misdiagnosed as PCLD, as a result of the clinical and radiological similarity between these disorders.CASE SUMMARY A 74-year-old female who had undergone nephrectomy for papillary-type RCC(PRCC) was suffering from abdominal pain and the recurrent intracystic hemorrhage of multiple cysts in the liver. Imaging studies and aspiration cytology of the cysts showed no evidence of malignancy. With a diagnosis of autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease, the patient received hepatectomy for the purpose of mass reduction and infectious cyst removal. Surgery was performed without complications, and the patient was discharged on postoperative day 14. Postoperatively, the pathology revealed a diagnosis of recurrent PRCC with cystic formation.CONCLUSION This case demonstrates the importance of excluding the cystic metastasis of a cancer when liver cysts are observed.

Key words: Polycystic liver disease; Polycystic kidney disease; Cystic metastasis; Renal cell carcinoma; Case report original w ork is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:http://creativecommons.org/licen ses/by-nc/4.0/

INTRODUCTION

Polycystic liver disease (PCLD) is defined as the presence of more than 20 cysts in the liver or the presence of more than 4 cysts in the liver with a family history of the disease. PCLD is a relatively rare disease, which is estimated to be present in 0.05%-0.53% of the total population[1]. PCLD manifests as clinical symptoms such as tiredness, fullness, shortness of breath, dissatisfaction with the abdomen size, limited mobility and early satiety, which significantly deteriorate the patient's quality of life[2].PCLD is classified as one of two inherited d isord ers, i.e., autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) and autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease(ADPLD). ADPLD is d istinguished from ADPKD by the absence of polycystic kidneys. The mutations present in polycystic kidney disease (PKD1 and PKD2) are causative genes for ADPKD, w hile 20% of ADPLD is caused by mutations in the protein kinase C substrate 80K-H (PRKCSH) or SΕC63, leaving the other 80% with unknown etiologies. PCLD, together with congenital hepatic fibrosis, is a type of disease that is characterized by the dysfunction of the primary cilium[3]. Current radiological and surgical interventions for “symptomatic” PCLD patients include aspiration-sclerotherap y, fenestration, hepatectomy and liver transplantation.Hepatectomy is usually indicated for Gigot type II PCLD, in which one liver segment is retained with unaffected liver parenchyma[4].

The diagnosis of PCLD is sometimes challenging. Typical differential diagnoses include ciliated hepatic foregut cysts, hepatobiliary cystadenomas, and parasitic cysts.However, in very rare cases, the cystic metastasis of a cancer becomes an important differential diagnosis that significantly changes the treatment strategy. The origins of cystic metastasis include colon, pancreas, ovary, kidney, neuroendocrine, and prostate cancer[1]. Here, we describe a rare case of the cystic metastasis of renal cell carcinoma(RCC), for which hepatectomy was performed due to the misdiagnosis of ADPLD.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 74-year-old female complained of right upper quadrant abd ominal pain w hen she presented at our hospital. Computed tomograp hy (CT) w ith intravenous contrast demonstrated the local recurrence of RCC in the ipsilateral lymph nodes and multiple liver cysts.

History of present illness

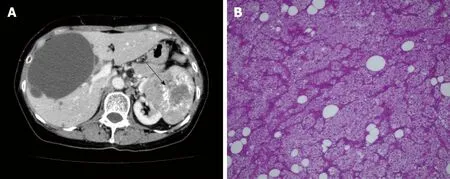

The patient was diagnosed with left renal cancer and liver cysts in the bilateral lobes 4 years p rior (Figure 1A). There w as one large cyst and several small cysts, as demonstrated by a CT scan. The liver cysts appeared as w ell-demarcated and w aterdense sacs w ithout mural nodules. The patient had not received health screening for 20 years. Left nephrectomy w ith ipsilateral adrenalectomy w as performed. Pathology revealed PRCC, G2, INF-α, p T2a, N0, M0, and v (-) (Figure 1B). No cysts were found in the excision. Εight months prior to the surgery, the p atient complained of right upper quadrant pain secondary to recurrent intracystic hemorrhage and received cyst aspiration and sclerotherapy. Aspiration cytology showed no evidence of malignancy,and the pain recurred soon after the treatment.

History of past illness

The patient had a medical history of hypertension and hyperlipemia.

Family history

The patient did not have a family history of PCLD.

Physical examination

The patient's temperature was 36.2 °C, heart rate was 82 bpm, respiratory rate was 14 breaths per minute, blood pressure was 140/99 mmHg and oxygen saturation in room air was 98%. A surgical scar was located in the left upper abdomen. In the abdominal examination, an abdominal mass w as observed in the umbilical region, shifting dullness was present and liver cysts were palpable.

Laboratory examinations

Blood analysis revealed anemia with a hemoglobin level of 7.8 g/d L, white blood cells at 2.3 × 109/L, with a normal hematocrit and platelet count. The prothrombin, partial thromboplastin times and d-dimers were normal. The serum albumin was low, at 3.2 mg/d L. In the blood biochemistry analysis, the lactate dehydrogenase was high, at 262 U/L, w ith a high alkaline phosphatase level, at 626 U/L, and a γ-glutamyl transpeptid ase rate of 101 U/L. The alanine aminotransferase and asp artate aminotransfer ase w ere normal. The u rine analysis w as nor mal. The electrocardiogram, chest X-ray and arterial blood gas were also normal.

Imaging examinations

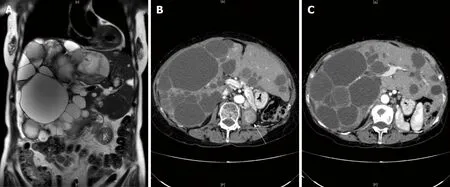

CT w ith intravenous contrast d emonstrated the local recurrence of RCC in the ip silateral lymph nod es and multiple liver cysts, w hich had increased in size and number (Figure 2A and B). The cysts were various in sizes, but the borders were clear,and there was no sign of enhancement in the cystic walls.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Considering the fact that multiple cysts existed, mainly in the right lobe, while normal liver areas were retained in the lateral section, the patient was classified as having Type II PCLD, based on Gigot's classification (Figure 2B and C).

TREATMENT

Tumor resection w ith lymp had enectomy w as p lanned to ensure the comp lete resection of the locally recurrent RCC. Further, w ith a d iagnosis of PCLD, right lobectomy combined w ith cyst fenestration w as planned to p rovid e an optimized method for alleviating the symptoms.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

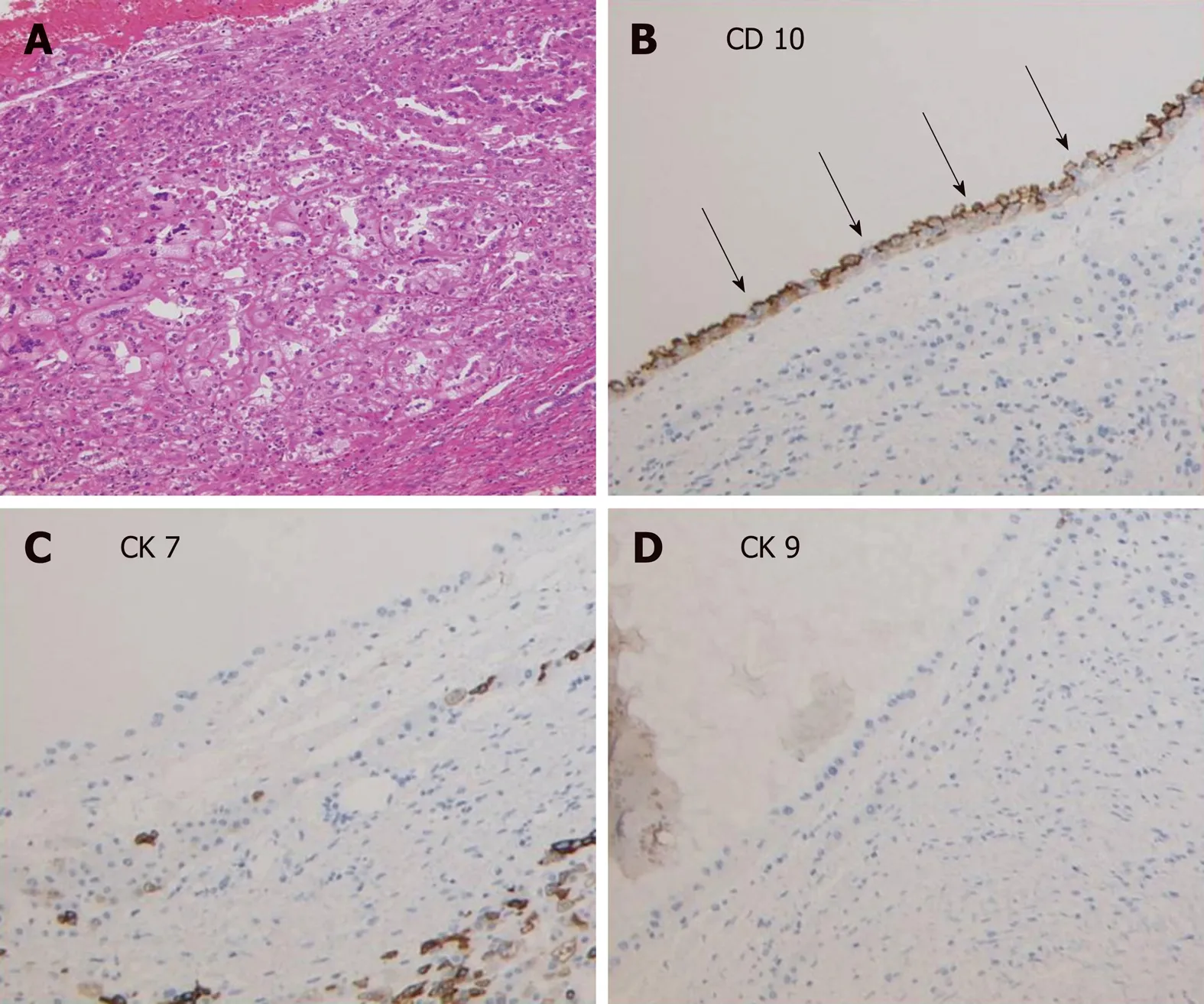

The surgery w as comp leted w ithout major intraop erative comp lications. In the pathological rep ort of the liver sp ecimens, cells located focally around the cysts formed tubule-papillary structures that w ere mostly lined w ith single-cuboid al or low-columnar epithelial cells with scant cytoplasm and uniform nuclei, w hich were morp hologically similar to PRCC by hematoxylin-eosin staining (Figure 3A)[5].Immunohistochemical staining showed the presence of CD10+cells in the edges of the cysts (Figure 3B), w hile CK7+and CK19+cells were absent (Figure 3B-D). Combined with the results of H&Ε staining, the diagnosis of PRCC liver metastasis was verified.The patient was discharged on postoperative day 14 and started sunitinib treatment 1 mo after the hepatectomy. It has been 2 years since the surgery w as performed. The pain was relived after the surgery, and the patient is still alive. How ever, lymph node metastases and lung metastases appeared after a few months, and the cysts occupying the remnant liver are grow ing, causing recurrent abdominal pain. The patient is now managed with symptomatic treatment.

Figure 1 Abdominal computed tomography of the liver and pathologic findings from the primary tumor. Abdominal computed tomography demonstrated left renal cancer (arrow) and bilateral liver cysts. A: There was one large cyst and several small cysts. The borders of the liver cysts were clear, with no mural nodules. B:Pathology of the primary tumor revealed papillary renal cell carcinoma, G2, INF-α, T2a, N0, M0, v (-), × 20.

DISCUSSION

PRCC is the second most frequent RCC subtype, followed by clear cell-type RCC(CRCC). PRCC is known to metastasize less frequently than CRCC, with a reported incidence of 5.7%-11%[6]. The lung and bone are common sites of metastases, whereas the metastasis of the liver is less frequent (16.1%)[6,7]. PRCC can be classified as having solid or cystic masses. Cystic-type PRCC may be a result of its inherent architecture or of cystic degeneration[6]. Cystic metastasis of RCC is very rare[7]. Some cases with cystic lymph node metastases or dissemination have been previously reported in the literature[8-11].

Liver cysts can be classified as d evelopmental, neoplastic, inflammatory, or miscellaneous[12]. The differential diagnosis of liver cysts is sometimes challenging,and excluding metastasis is one of the highest priorities. In typical cases of cystic metastatic cancers, the borders of the cystic lesions are typically heterogeneous and ill-defined[13]. The cystic walls are irregular, and the vessels are amputated; however,these characteristics are not observed in cases of PCLD. Cystic metastases usually have a peripheral enhancing rim on the arterial phase of a CT scan and magnetic resonance imaging, while PCLD usually does not have this feature[14]. Peribiliary cysts,which are also seen with high incidence, are usually located at the hilum and adjacent to the hepatic ducts, and the cyst sizes are smaller than 10 mm[13,14]. The misdiagnosis of cystic liver disease can be critical since the treatment strategy is completely different.

We described a rare case of the cystic metastasis of PRCC, which was misdiagnosed as PCLD. This case is important in that it demonstrates that PRCC can manifest with different presentations at metastasis and recurrence, i.e., multiple cyst formation,imitating PCLD[7,13]. In our case, the preoperative images of the liver cysts indicated that there were clear borders with no signs of enhancement in the cystic walls, which were characteristically similar to the cysts of PCLD, and the aspiration cytology was negative for cancer cells. Pathologically, the cystic walls were irregular, and the cells around the cysts were morphologically compatible with RCC. The diagnosis of RCC w as confirmed by the p resence of CD10+cells around the cysts, w hich is a characteristic surface marker of RCC. It was quite unlikely that cystic liver metastasis occurred to a liver affected by PCLD, since all the cysts that were pathologically investigated showed the malignant characteristics described above. Since CA 50 was reported as a potential tumor marker for cystic RCC[15], we could have tested the CA 50 in the blood and the cystic fluid from repeated fine-needle aspiration. Further,18Ffluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography/CT (PΕT/CT) is highly sensitive and accurate, with a sensitivity of 97% and a specificity of 75% for hepatic metastasis[10]. It has been reported to show intense uptake in cystic liver metastasis compared w ith that in benign cysts[16]. We could have checked PΕT/CT scan to confirm the malignancy of the cysts if we had taken metastasis into consideration.

Figure 2 lmages from abdominal computed tomography. Local recurrence of renal cell carcinoma was detected in the ipsilateral lymph nodes and in the left lumbar vertebra (B, white arrow). There was a diffuse involvement of the liver parenchyma, with multiple cysts and large areas of noncystic liver parenchyma remaining (C); A: coronal view; B and C: transverse view.

The treatment for metastatic renal cancer is debated, and the therapeutic options are limited. The National Health Service of Εngland Guidelines stated that sunitinib and pazopanib are first-line systemic therapies for metastatic RCC[17]. Complete resection is the only choice for patients with metastatic RCC to have a satisfactory prognosis, with 5-year overall survival rates of 15 to 60%[18]. However, patients with bilateral multiple metastatic RCC, such as our patient, are not cand id ates for hepatectomy because radical resection cannot be performed, and the surgery will not prolong the overall survival time of the patients[19,20]. In our case, since the patient suffered from acute abdominal pain and recurrent intracystic hemorrhage, w e performed hepatectomy following the diagnosis of PCLD. However, as the cysts were located diffusely in the bilateral lobe, the patient would have had no indication for hepatectomy if she had been correctly diagnosed with PRCC preoperatively. We should have started with chemotherapy and palliative care, using opioids and additional adjuvants to alleviate the abdominal symptoms[21]. This case reminds us of the following: first, when multiple cystic lesions are observed throughout the liver parenchyma in patients with cancer, it is important to first exclude metastasis; and second, some specific types of cancer can show different presentations at metastasis and recurrence, which could cause preoperative misdiagnosis.

CONCLUSION

In a patient w ith cystic neoplasms of the liver, the diagnosis remains challenging in everyday practice. Cystic lesions may present as solitary or multiple cysts and may range from benign to malignant. To the best of our know ledge, this is the first report of cystic liver metastasis from PRCC. The most important implication of this case is that PCLD must be distinguished from the cystic metastasis of a cancer, which can contribute to a p rofound ly better p rognosis as a result of the use of an optimal treatment approach.

Figure 3 Pathological findings from the metastatic liver cysts. A: Cells around the cysts showed a basophilic morphologic appearance with low-grade nuclear features that were morphologically consistent with papillary-type renal cell carcinoma cells, × 20. B-D: Immunohistochemical staining showed the occasional presence of CD10+ cells in the edges of the cysts, while CK7+ and CK19+ cells were not observed, × 20.

World Journal of Gastroenterology2019年18期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2019年18期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Alteration of the esophageal microbiota in Barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma

- lnflammatory bowel diseases and spondyloarthropathies: From pathogenesis to treatment

- Harnessing the potential of gene editing technology using CRlSPR in inflammatory bowel disease

- Diversity of Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM l-745 mechanisms of action against intestinal infections

- Characteristics of mucosa-associated gut microbiota during treatment in Crohn's disease

- Role of abdominal ultrasound for the surveillance follow-up of pancreatic cystic neoplasms: a cost-effective safe alternative to the routine use of magnetic resonance imaging