lnflammatory bowel diseases and spondyloarthropathies: From pathogenesis to treatment

George E Fragoulis, Christina Liava, Dimitrios Daoussis, Euangelos Akriviadis, Alexandros Garyfallos,Theodoros Dimitroulas

Abstrac t Spondyloarthropathies (Sp A) include many different forms of inflammatory arthritis and can affect the spine (axial Sp A) and/or peripheral joints (peripheral Sp A) with Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) being the prototype of the former. Εxtraarticular manifestations, like uveitis, psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease(IBD) are frequently observed in the setting of Sp A and are, in fact, part of the Sp A classification criteria. Bowel involvement seems to be the most common of these manifestations. Clinically evident IBD is observed in 6%-14% of AS patients, which is significantly more frequent compared to the general population. Besides, it seems that silent microscopic gut inflammation, is evident in around 60% in AS patients. Interestingly, occurrence of IBD has been associated with AS disease activity. For peripheral Sp A, two different forms have been proposed with diverse characteristics. Of note, Sp A (axial or peripheral) is more commonly observed in Crohn's disease than in ulcerative colitis. The common pathogenetic mechanisms that explain the link between IBD and Sp A are still ill-defined. The role of dysregulated microbiome along with migration of T lymphocytes and other cells from gut to the joint (“gut-joint” axis) has been recognized, in the context of a genetic background including associations with alleles inside or outside the human leukocyte antigen system. Various therapeutic modalities are available with monoclonal antibodies against tumour necrosis factor, interleukin-23 and interleukin-17, being the most effective. Both gastroenterologists and rheumatologists should be alert to identify the coexistence of these conditions and ideally follow-up these patients in combined clinics.

Key words: Spondyloarthropathies; Axial spondyloarthropathies; Peripheral spondyloarthropathies; Ankylosing spondylitis; Inflammatory bowel disease http://creativecommons.org/licen ses/by-nc/4.0/

INTRODUCTION

Und er the term sp ond yloarthrop athy (Sp A) are classified many inflammatory arthrop athies w ith similar clinical and imaging features. How ever, d iagnostic laboratory or pathological find ings w ith high sp ecificity are lacking. Sp A affects mainly the spine, but symptomatology from the p eripheral joints as w ell as from entheses and other tissues might occur. Sp A includ e: p soriatic arthritis (PsA),perip heral Sp A, enterop athic [also know n as inflammatory bow el d isease (IBD)-related] arthritis, reactive arthritis, undifferentiated spond yloarthropathy and axial sp ondyloarthropathy (axSp A) w hich includ es non-radiographic axial spond yloarthropathy (nraxSp A), and Ankylosing spondylitis (AS)[1]. The latter is considered the prototype of these diseases[2]. Εnthesitis (inflammation of the entheses which are the insertions of the ligaments and tendons into the bone) is thought to be one of the key manifestations in Sp A, help ing to d istinguish from other inflammatory arthropathies[1]. Apart from the skeletal disease, extra-articular manifestations like uveitis, psoriasis and inflammatory bow el disease often occur[2], offering significant help in the diagnosis of these diseases and being part of their classification criteria[3,4].Of note, IBD contributes to the diagnosis of axSp A, as it has a positive likelihood ratio of 4.3 for axSp A diagnosis in patients with chronic low back pain[5,6].

Accord ing to the latest Assessment of Spond yloArthritis Society (ASAS) criteria,Sp A can be classified to axSp A or peripheral Sp A. The former pertains to patients w ith low back p ain for ≥ 3 mo and age of onset < 45 years old and requires either sacroiliitis on imaging and at least one other Sp A feature (e.g., dactylitis, enthesitis) or positivity for HLA-B27 and at least tw o other Sp A features (Table 1)[4]. Difference between nraxSp A and axSp A is the lack of radiographically confirmed sacroiliitis in the former. Und er the term “peripheral Sp A” are classified patients w ithout current low back pain, with peripheral arthritis, or enthesitis or dactylitis plus at least one or tw o of the follow ing Sp A features: (uveitis, psoriasis, crohn´s d isease/ulcerative colitis, preceding infection, positive HLA-B27, sacroiliitis on imaging) or (arthritis,enthesitis, d actylitis, inflammatory back p ain in the p ast, family history of Sp A),respectively[3].

It is w ell known that there is a close association between IBD and Sp A[7]. Purpose of our review w as to present in d etail the existing epidemiological data and treatment approaches to these patients and to delineate the current d iagnostic challenges. Also,w e aimed to d escribe the und erlying p athogenetic mechanisms that have beensuggested to link these two entities.

Table 1 Assessment of Spondyloarthritis lnternational Society Classification criteria for axial spondyloarthropathy and peripheral spondyloarthropathy

IBD AND SPA: EPIDEMIOLOGY, AND ASSOCIATION WITH DISEASE CHARACTERISTICS

IBD in the context of SPA

IBD [including Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC)] is not rare in AS,with its prevalence ranging from 6%-14%[2,6,8,9]. In detail, in a large population, controlmatched study, including 4101 patients with AS, Stolwijk et al[6]found that at the time of AS diagnosis, the cumulative incidence was 4%. Additionally, in a French large,prospective study for early inflammatory back pain, IBD occurred in 7.2% of patients with newly diagnosed AS[10]. Furthermore, in an early axSp A cohort frequency of IBD was calculated to be 2.6% (1.7% for AS and 0.9% for nraxSp A, difference was not significant)[11]. In fact, it has been suggested that the risk for IBD is more pronounced in the first years of AS diagnosis and falls at baseline levels approximately 10 years after[6]. However, this has not been confirmed by a SLR and meta-analysis[2]. In that,Stolwijk et al[6]found that prevalence of IBD in AS was 6.8% (95%CI: 6.1%-7.7%),which is much higher than the percentages observed in the general population (0.01%to 0.5%). Likewise, in a large population study was shown that the incidence rate of IBD was 5.3-fold increased to the AS patients compared to healthy controls. For nraxSp A the results seem to be largely similar. In a meta-analysis addressing the prevalence of extra-articular disease in nraxSp A versus AS, it w as found that IBD was almost equally frequent (p ooled p revalence d ifference of 1.4% in favour of AS)between these tw o entities[8].

The question remains open whether we can predict which Sp A patients suffer from or will develop IBD. Stolwijk et al[6]2014 found that IBD was in general more common in males and that its frequency d ecreases w ith age, in AS. In a multi-centre AS study w ith a long follow-up, no d ifferences w ere record ed betw een p atients w ho had a history of IBD at baseline and those who did not[9]. On the other hand, development of IBD was associated with disease activity and spinal pain scores at baseline and worse physical function and patient well-being, at the time of IBD diagnosis[9]. Additionally,in a case control stud y[12]it w as found that anterior uveitis w as less frequent in patients w ith IBD-related spond yloarthropathy compared to those with Sp A w ithout bow el involvement[12]. Interestingly, in a sub-analysis of the GIANT cohort, it w as shown that in patients w ith axSp A, there is a link between bone marrow edema of the sacroiliac joints and the gut inflammation. For this, SPARCC (Sp ond yloarthritis Research Consortium of Canad a) scores w hich is a tool to measure MRI-d efined sacroiliitis and ileocolonoscopy were used, respectively. It was found that SPARCC scores w ere higher in p atients w ith chronic gut inflammation, comp ared to those without gut lesions[13].

Clinically silent IBD in SPA

Despite clinically evid ent IBD in the context of AS is observed in less than 15%, it has been suggested that clinically silent macroscopic and microscopic gut inflammation occurs in about 60% of AS patients[14-16]. From them, 5%-20% w ill develop CD within 5 years[17,18]. Microscopic gut inflammation, in axSp A, has been associated w ith younger age, male gender, progressive disease, early disease onset, radiologic sacroiliitis, high disease activity as assessed by the BASDAI and restricted spinal mobility measured by the Bath Ankylosing Sp ond ylitis Metrology Ind ex[9,16]. No association w as id entified with other extra-articular features or with the status of HLA-B27. Results were comparable between nraxSp A and AS[16].

SPA occurring in patients with IBD

Seeing the opposite flip of the coin, Sp A is encountered in about 10-39% of patients w ith IBD, being the most frequent extra-intestinal manifestation in these individuals[16,19-25]. Sp A is more commonly observed in patients with CD compared to those with UC[26-28]. Axial/arthritis symptomatology usually follows IBD diagnosis,but in about 20% the opposite is the case[19,23]especially for axial disease[20]. In general,AS and sacroiliitis (symptomatic or not) is estimated to occur in about 2%-16% and 12%-46% of IBD patients, respectively[19,20,22,23,27,29], both being more common in CD than in UC[19,30]. In a recent meta-analysis, it was show n that prevalence of AS and sacroiliitis in IBD were 3% (95%CI: 2%-4%) and 10% (95%CI: 8%-12%), respectively.

Comparing CD patients with and without AS, in a small single centre study, Liu et al d id not observe any differences betw een these tw o groups[31]. Of note, they demonstrated that there was a significant correlation between disease activities of these two entities. These were measured by CD activity index for CD and w ith BASDAI for AS. They also showed that activity of CD significantly correlated with functional disability in AS, as assessed by Bath AS functional index - BASFI. All these possibly imply that there is a tight connection in the pathogenetic mechanisms of these conditions.

On the other hand, in a study examining possible associations between clinical and other characteristics with the occurrence of AS or SI in patients with CD, it was found that there was an association between SI and peripheral arthritis as well as between AS and uveitis, in these patients[32]. Besides, it has been suggested that in CD patients,colitis is more commonly associated with arthritic involvement compared with patients suffering from ileitis, while regarding UC, it seems that isolated proctitis is rarely combined with rheumatic manifestations[20,23].

Finally, patients with IBD-related ankylosing spondylitis and IBD-related isolated sacroiliitis are HLA-B27 positive in about 25%-78% and 7%-15%, respectively[20,22,32,33],possibly suggesting that isolated sacroiliitis is of different nature compared to AS in the setting of IBD[23]. These percentages are also lower compared to the prevalence of HLA-B27 observed in patients with AS which range from 80%-90%[1,20,34-36].

Peripheral Sp A is also common in IBD with its prevalence ranging from 0.4% to 34.6%[19,28,37]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that the pooled prevalence of peripheral arthritis, in the context of IBD was 13% (95%CI: 12%-15%)with its prevalence being much higher in the younger ages: 25% (95%CI: 19%-32%)and 2% (95%CI: 1%-5%) for age group s betw een 20-30 and 50-60 years old,respectively[30]. As observed for axial disease, peripheral Sp A is more common in CD compared to UC[28,30,38]. A large retrospective study in the IBD Oxford clinics, had shown that peripheral arthritis occurred in 10% and 6% of patients with CD and UC,respectively[38,39]. This study, led to id entification of tw o major groups of perip heral arthritis in the context of IBD, namely: oligoarticular (< 5 joints are affected) and polyarticular (≥ 5 joints are affected)[20]. Some authors suggest that in the first group,w hich is more frequent than the second[39], arthritis is usually asymmetrical, nonerosive, affects low er limbs[20]and is associated with IBD activity and positivity for HLA-B27[23,39]. Patients belonging in the second group tend to have a more chronic course and be destructive and unrelated w ith IBD activity and HLA-B27 status[38].Furthermore, Yüksel et al[28], examining the characteristics of perip heral arthritis in patients w ith IBD, they found that erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum w ere more commonly observed in IBD p atients w ho also had perip heral arthritis,compared to those w ithout. Various risk factors have been reported for peripheral arthritis in the context of IBD including: family history of IBD, ap pend icectomy,smoking and presence of other extra-intestinal manifestations[19,40,41].

Finally, some IBD p atients might exhibit clinical features of Sp A (e.g., dactylitis)w ithout fulfilling d iagnostic criteria for Sp A[20,42]. The frequency of d actylitis in patients w ith Sp A in the context of IBD varies from 0% to 15.5%, but it seems to be around 5%[12,30]and therefore less common than in patients w ith Sp A without IBD[12].Incid ence of enthesitis also varies largely, among d ifferent stud ies, in these patients[12,30]. A case control study[12]found that enthesitis w as also less frequent in IBD-Sp A patients compared to Sp A ind ivid uals without IBD. For both dactylitis and enthesitis, no d ifferences in their frequency w ere d etected betw een CD and UC patients, w hile they occurred more frequently in patients w ith IBD and psoriasis compared to the IBD patients without skin disease[12].

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

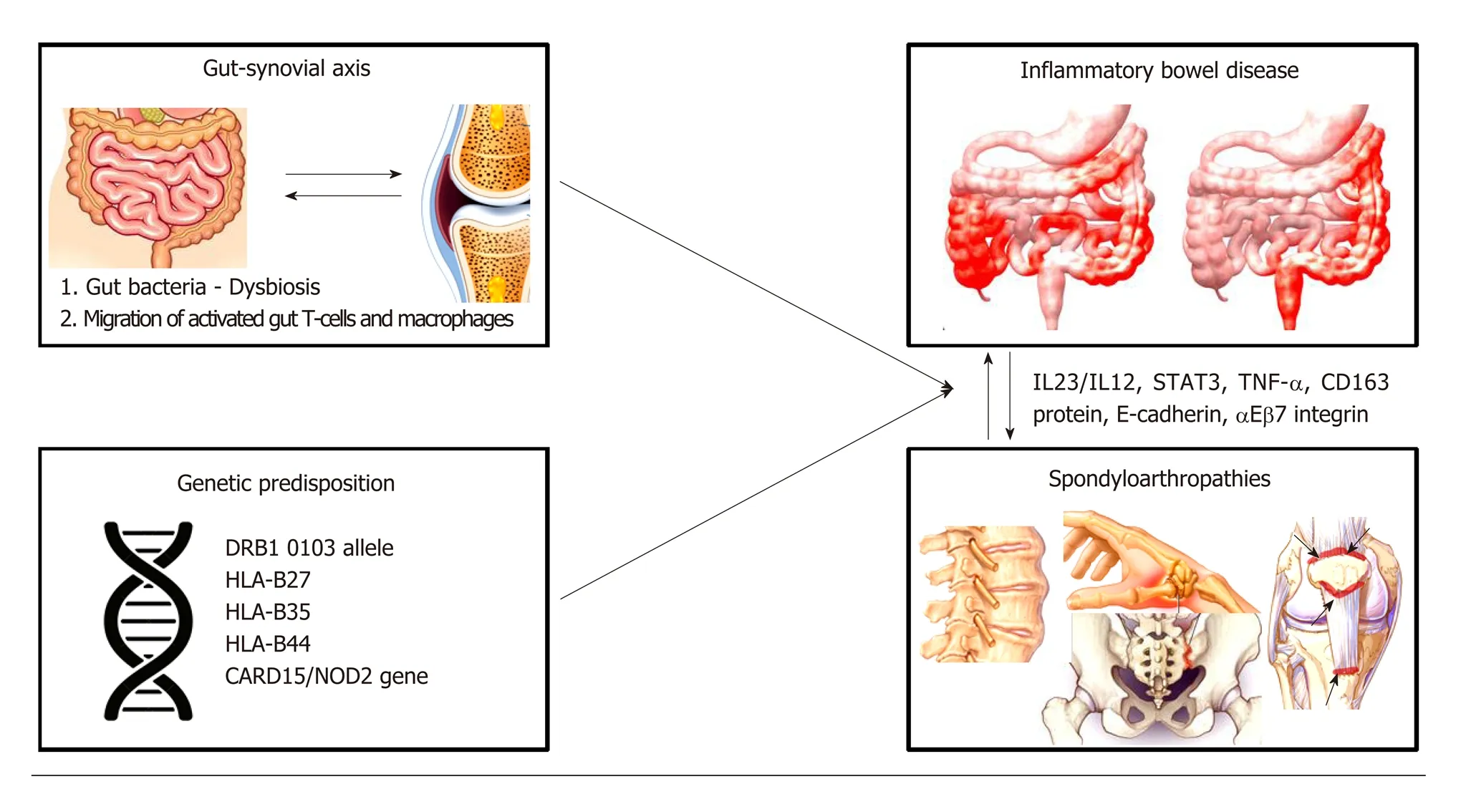

The pathophysiology of spondylathropathies associated with IBD involves the socalled ‘'gut-synovial axis'' hypothesis, which implicates environmental and host factors. Many of them act as triggers lead ing to initiation of inflammation in genetically predisposed individuals (Figure 1). Several studies have confirmed the link between joint and gut inflammation. It seems likely that both bacterial antigens and reactive T-cell clones, activated into the gut home the joint. However, the exact immunological mechanisms linking gut and joint inflammation are not fully understood[43,44].

Genetic predisposition

Genetic predisposition seems to carry a significant role in linking these conditions. In a large genotyping study, investigating risk variants for AS, it was shown that many of these w ere also linked with CD and UC[45]. Add itionally, in a genealogic study in Iceland it w as show n that first and second-degree relatives of patients w ith AS had increased risk (3.0 and 2.1, respectively) for IBD and vice versa[46].

Genetic factors play an important role, through alterations in both the adaptive and innate immune pathw ays[43,44]. Certain human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles have been recognized in patients w ith IBD w ho are at higher risk for having Sp A. As mentioned, 25%-78% of p atients w ith AS and IBD are p ositive for HLA class I molecule B27 (HLA-B27)[23,43,44]. Furthermore, MHC class II allele DRB1 0103 along w ith HLA-B35 and HLA-B27 are frequently associated w ith typ e I p erip heral arthritis[23,47,48], w hile approximately 38% of patients w ith active UC or CD have been identified as carrying the allele DRB1 0103. On the other hand, typ e II p eripheral arthritis is associated with HLA-B44[44,49].

Genetic factors outsid e the HLA system, have also been described. Variations of CARD15 gene (w hich encod es the protein product NOD2) increase the risk of CD about 4-40 times and has been linked to the d evelop ment of sacroiliitis in IBD patients[50-52]. In add ition, patients with AS and CARD15 mutations are at higher risk for subclinical intestinal inflammation[44,51,53]. NOD2 is an intracellular receptor for bacterial molecules and is expressed in the surface of macrophages, lymp hocytes,paneth cells and intestinal epithelial cells. This receptor p lays a role in the innate immune response by activating nuclear factor-κB (NFκB) w hich is a transcriptional regulator of a large variety of genes encoding pro-inflammatory cytokines, adhesion molecules, cytokines, grow th factors and enzymes)[43,44,48,51,54]. As a result, NOD2 protein is resp onsible for p ositive regulation of immune d efense in the gut and induction of a pro-inflammatory state[54]. How ever, though NOD2 gene mutations are associated w ith the clinical expression of CD in 20%-30% of p atients there is no established association betw een presence of NOD2 mutations and d evelop ment of Sp A in IBD patients[44,51,55].

Figure 1 Pathogenic mechanisms linking gut and joint inflammation. The pathogenic link between spondyloarthropathies (SpAs) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) involves the so-called ‘’gut-synovial axis’ hypothesis. Various environ mental (gut bacteria-dysbiosis) and host factors (migration of activated gut-T cells and macrophages) leading to initiation of inflammation in genetically predisposed individuals may act as triggers of inflammatory responses against gut and joints components. IBD patients carrying specific human leukocyte antigens (HLA) alleles (such as DRB1 0103 allele, HLA-B27, HLA-B35, HLA-B44) and mutations of the CARD15/NOD2 gene are at higher risk of developing SpAs. Recently, up-regulation of adhesion molecules (E-cadherin, αEβ7 integrin), increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor-α), macrophages expressing CD163 protein, interleukin (IL)-12/IL-23 signaling pathway and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 protein have also been implicated in the pathophysiology of SpAs in IBD patients. IL: Interleukin; STAT: Signal transducer and activator of transcription; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; HLA: Human leukocyte antigen; CARD15: Caspase recruitment domain-containing protein 15; NOD: Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2.

Furthermore, CD, AS and PsA have been associated with polymorphisms in some common genes like IL-23R, IL-12B, STAT3, and CARD9, all of them implicated in the anti-IL-23/IL-17 axis[56-60].

Having said that, IL-23/-17 axis seems to play an important role in both axSp A and IBD (regard ing the latter, the evid ence mainly pertains to CD rather than UC)[61-63].This axis is mainly regulated by IL-23, resulting in the production of IL-17, IL-22 and to a lesser extent of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)[1]by the so-called Th17 cells, which are a subgroup of T-helper cells. These cytokines are also prod uced from other cells like innate lymphoid cells[64]. In the gut of patients w ith CD or patients w ith Sp A, it has been observed increased expression of IL-23[65]. Similarly, in the peripheral blood of AS patients there is increased number of Tγδ cells expressing IL-23R and producing IL-17; ad d itionally, increased exp ression of IL-23 is noticed in p atients' facets.Interestingly, it seems that there are some cells able to produce IL-17 irrespective of the presence of IL-23. This, as d iscussed below, might has some implications in the therapeutic approach of these patients[66].

Links between the gut and the joints

Several other find ings also highlight the common und erlying p athogenetic mechanisms betw een IBD and Sp A. aΕβ7 integrin w hich is exp ressed by intraep ithelial T cells in the intestinal mucosa and bind s to the glycop rotein Εcad herin exp ressed by gut epithelial cells, has been found to be upregulated on colonic T cells from AS patients and also from lymphocytes obtained from synovial tissue of Sp A patients[67,68]. The Ε-cadherin molecules have been also observed to be up-regulated in the gut of patients w ith IBD and Sp A individuals with subclinical gut inflammation[51,67-69].

In another stud y increased levels of macrophages expressing the protein CD163 have been reported in both gut mucosa of IBD patients with and without Sp A and in the synovial tissue and gut from Sp A patients[51,70,71]. Finally, animal mod els have shown that prolonged exposure to the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α might lead to a phenotype resembling IBD-Sp A[72]. In the last d ecade, it w as recognized that a common target of this cytokine could be the synovial fibroblasts and the intestinal myofibroblasts[68,73].

The Gut-synovial axis

Tw o - probably complementary- theories have been formulated to explain the development of Sp A in patients with IBD. These theories include both alterations in gut bacteria and migration of gut lymphocytes to the joint[43,44]. Changes in the gut microbiome, w hich is also know n as dysbiosis, have been associated w ith Sp A. In detail, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii has been found to be in red uced numbers, in stools of Sp A patients[18,74,75]. Also, in AS patients, increased numbers of Dialister microbes in ileal and colon biop sies have been correlated w ith Ankylosing Spond ylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS)[18,75]and of Ruminococcus gnavus in the stools w ith Bath Ankylosing Sp ondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI)[18,76,77]. Furthermore, other stud ies have detected in the inflamed joints of these p atients certain bacteria like Yersinia enterocolitica, Salmonella enteritidis and typhimurium, or antigens related to them[26,78,79]. Role of microbiome in the pathogenesis of Sp A is also supported by d ata from animal mod els. For examp le, the arthritis and inflammatory colitis features developed in HLA-B27 transgenic rats are ameliorated when they are raised in germfree cond itions[18,80]. These observations suggest that gut and joint inflammation process d ep end s on the p resence of bacteria into the gastrointestinal tract, w hich emphasizes the role of autoimmunity and antigen mimicry[26,44].

The second hypothesis is based on experimental studies w hich show ed that gut Tcells activated by antigens migrate to the joints and induce inflammation[43,44,51]. In state of inflammation alterations occur in the mucosal vasculature, such as vasodilation,hyp eremia and increased vascular p ermeability w hich are ind uced by various inflammatory cytokines, resulting in enhanced extravasation of leukocytes.Furthermore, the migration p athw ays of lymp hocytes are altered by aberrant expression patterns of adhesion molecules, inflammatory cytokines and receptors[51]. It is know n that integrins α4β7 and αΕβ7 and Mad CAM-1 mucosal vascular receptor play an important role in the lymp hocytes' gut homing. It has been show n that leukocytes populations from inflamed gut can bind to synovial vessels and home into the joint, using multip le ad hesion molecules[81], such as αΕβ7 integrins, vascular adhesion protein-1 (VAP-1) and intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1/CD54)[26].The increased number of T cells expressing αΕβ7 integrins in the synovial membrane is in favor of the mucosal origin of these cells, how ever this hypothesis remains to be proven[68].

Additionally, It has been show n that macrophages from the gut of IBD patients are able to ad here in end othelial cells of synovial tissue[81], further enhancing the activation of T cells locally[26]. Collectively, one could argue that gut T-cells are activated in the Peyer's p atches and mesenteric lymph nod es, express a pattern of ad hesion molecules that und er sp ecific cond itions lead s to migration of these activated T-cells into the joint causing inflammation[43,44,51,82]. Further stud ies are needed to fully understand the pathogenic pathways linking IBD and Sp A.

TREATMENT

Given the common pathogenetic mechanisms underlying Sp A and IBD, therapeutic approach to these entities is largely similar. However, there are some differences in the safety and efficacy of the various treatment modalities used.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) although commonly used in Sp A,should be generally avoided in IBD especially in the active ones, but short courses(e.g., 2 wk) do not seem to cause exacerbations[20]. On the other hand, short courses of systemic steroids, although demonstrate some efficacy for CD or UC are not effective for axSp A[20,83]. Local steroids injections and low doses of systemic steroids have been used for peripheral Sp A[20].

The most common conventional Disease mod ifying antirheumatic d rugs(DMARDs) used for treatment of Sp A are methotrexate and sulfasalazine, both demonstrating some efficacy for peripheral but not for axial Sp A[84,85]. Furthermore,methotrexate has proved to be helpful in inducing and maintaining remission in CD patients[86,87]but is not recommend ed as first line treatment of UC. Similarly,sulfasalazine has some efficacy in CD (but not for ileal CD)[20]and UC[88,89].

Anti-TNF regimes are the gold-standard treatment for the patients with co-existing IBD with Sp A who are not controlled with conventional DMARDs. All of them are approved for the treatment of axSp A[90]while infliximab and adalimumab are the most well studied for patients with IBD, both having indication for CD and UC[87].Εtanercept, was not effective for IBD[91]. Many hypotheses have been made to explain its lack of efficacy, including that this might be related to its insufficiency to induce apoptosis in the T cells of the lamina propria[92]. Also, etanercept blocks both TNFa and TNFb. The latter seems to regulate, in the lamina propria, T-cell dependent IgA production, which in turn controls the intestinal microbiota composition[93,94].

Interestingly, new onset IBD in the context of AS, has been observed in patients who started treatment with anti-TNF reagents[95,96]. These cases were more frequently resembling CD rather than UC and have been associated with commencement of etanercep t[97-99]. Of note, a large multicentre AS stud y examining the presence and development of extra-articular manifestations d id not find any correlation betw een biologics use and development of IBD[9]. Whether there is a true association betw een treatment w ith anti-TNF d rugs in AS patients and new-onset of IBD, remains to be defined.

The role of the IL-23/-IL-17 axis in the pathogenesis of Sp A and IBD is supported by many stud ies of basic and clinical research[61]. Desp ite, monoclonal antibodies targeting the key cytokines of the axis (i.e., IL-23 and IL-17) were thought to be very effective, data from clinical trials d id not fully support this notion. Ustekinumab, a monoclonal antibody against the common p40 subunit of IL-12 and IL-23, has proved to be effective for CD but d oes not appear to w ork for AS. Although d ata d erived from post hoc analyses of phase 3 trials in patients w ith psoriatic spond ylitis w ere promising, ustekinumab did not achieve the primary endpoint in phase 3 trials for AS and non-rad iograp hic ax Sp A[100]. Similarly, risankizumab, w hich is an antibod y specifically targeting the p19 subunit of IL-23 failed to show clinical and radiological efficacy in a phase 2 trial for AS[101]. Data from clinical trial about other antibod ies against p19 subunit of IL-23 are eagerly aw aited. To explain the differences observed in the efficacy of anti-IL-23 betw een psoriatic spondylitis and AS, it is not irrational to speculate that the pathogenetic mechanisms underlying AS are somewhat different to those of spondylitis in the context of PsA.

Secukinumab, w hich is a monoclonal antibod y against IL-17 recently received approval for AS and therefore is another therapeutic option in patients with axSp A.Phase 3 trials are now und erw ay for secukinumab in nraxSp A. One could expect,based on the underlying pathogenetic mechanisms that secukinumab w ould have good results in CD. How ever, results in phase 2 trials w ere negative w ith the d rug being numerically worse than placebo. Many hypotheses have been formed to explain the failure of secukinumab in CD. Candida albicans proliferation has been proposed as a p lausible explanation for the CD exacerbation given the role of IL-17 in fighting fungal infections[61,102]. Although new cases of IBD in axSp A p atients treated w ith secukinumab have been described[103], a recently published study analysing data from 21 clinical trials from patients w ith p soriasis, p soriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis, has show n that exposure adjusted incidence rates for IBD did not increase over time w ith secukinumab treatment[104]. Interestingly, a recent study provid ed some evid ence supp orting that supp ression of IL-17F but not IL-17A w as ind eed protective for colitis by ind ucing T regulatory cells via mod ifications in colonic microbiota[105].

An obvious question is how ustekinumab, which blocks IL-23 and subsequently IL-17 works for CD but secukinumab does not? There is accumulated evidence that IL-17 can be produced also -to a lesser extent p ossibly- in an IL-23 ind ependent manner from innate lymp hoid, T γδ or other types of cells[64,106]. Therefore, blocking IL-23 leaves some “basal” levels of IL-17. Lee et al[107]have show n, that T γδ cells in the lamina propria are the prod ucers of gut-protective IL-17, in an IL-23 independent w ay. Its effect is possibly mediated through regulation of the tight-junction protein“occludin” w hich maintain barriers integrity.

Vedolizumab, a gut selective α4β7 integrin antagonist, has show n to be effective in patients w ith CD[108,109]and for ind ucing or maintaining therapy in UC patients[110].Results of this d rug in articular symptoms are somew hat conflicting. Whether this drug is linked w ith exacerbation or new-onset arthralgias or inflammatory arthritis remains to be answered[87,111-113]. Of note, a recent post hoc analysis of the “Gemini”trials show ed that vedolizumab was associated w ith decreased likelihood of new or worsening arthritis/arthralgia in CD patients w hile in UC the incidence was similar between patients treated with the active drug or with placebo[114].

JAK inhibitors are a new d rug class category w ith p romising results in various immune mediated diseases. Genome wide association stud ies have show n that there is association betw een CD and single nucleotid e p olymorphisms in the JAK-STAT pathw ay[115]. Results in a p hase 2 trial for CD has show n that tofacitinib w as not effective[116]. How ever, new er and more selective JAK-inhibitors, like filgotinib and upadacitinib have favorable results in achieving clinical remission in phase 2 trials for CD[117,118]. For UC, tofacitinib after the promising results with patients achieving higher rates of clinical remission and clinical response compared to placebo[119]received Food and Drug Ad ministration (FDA) ap proval for p atients w ith mod erate to severely active UC.

As regards to the efficacy of JAK-inhibitors in Sp A, tofacitinib has shown favorable results in phase 2 trials of AS w ith 80.8% of the p atients treated w ith tofacitinib achieving ASAS20 improvement at w eek 8, comp ared to 41.2% of p lacebo-treated patients[120]. Recently published results from a phase 2 clinical trials show ed also that filgotinib w as effective for AS w ith p atients exp eriencing significant clinical improvement, compared to placebo, at week 12. A phase 2b/3a clinical trial assessing the efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in patients w ith AS is currently und erw ay(NCT03178487). Whether JAK-inhibitors could be another potential therapeutic option in patients with IBD and Sp A remains to be defined from future studies.

DIAGNOSIS - THE ROLE OF CALPROTECTIN

Although colonoscopy is being considered as the gold-standard for IBD diagnosis, a recent study has shown that capsule endoscopy was superior to classical colonoscopy in diagnosing CD in the context of Sp A. It was shown that small bowel inflammation was present in 42.2% and 10.9% of the patients who underwent capsule endoscopy and classical colonoscopy, respectively. Interestingly, positive findings were not associated with symptomatology from the gastrointestinal system but with elevated faecal calprotectin levels, confirming that many Sp A patients have “silent” IBD[121].Calprotectin measured in the serum or in the stools has been used to identify subclinical bowel inflammation in patients with Sp A. Cypers et al[14]have found that elevated serum calprotectin levels have been associated with subclinical microscopic colitis in Sp A patients. In detail, individuals who had both CRP and calprotectin elevated had a frequency of bowel inflammation of 64% compared to 25% in patients who had low levels of these proteins. Additionally, in patients who had high levels of either serum calprotectin or CRP, frequency of bowel inflammation was significantly higher in Sp A patients with high faecal calprotectin compared to those with low[14]. In a recent study, Ostgard et al[122]confirmed that faecal calprotectin could serve as a biomarker to identify patients with subclinical bowel inflammation. It has to be noted however that faecal calprotectin levels can be influenced by NSAIDs use, which is quite common in Sp A patients[123]. Interestingly, patients w ith elevated faecal calprotectin levels had more inflammation in the sacroiliac joints compared to those with low levels. Also, the former had better response to adalimumab as assessed by ASDAS. It has to be said however, that these patients received an extra loading dose of 80 mg adalimumab, at baseline[122]. The concept of calprotectin as biomarker of treatment response has been suggested also previously: In proof of concept trials for Sp A, serum calprotectin has been found to be decreased after treatment of axSp A and peripheral Sp A with infliximab and etanercept, respectively[124].

DISCUSSION - POINTS TO CONSIDER

It is increasingly being recognized that there is a very close link between IBD and Sp A. As outlined in this review, there are several hints for that: epidemiological,clinical, laboratory (i.e., positivity for HLA-B27) histopathologic and pathogenetic.Regarding the latter, it is very intriguing to define to which extent these are common betw een these entities and identify the diversities that lead to different clinical expressions. However, many limitations impede this venture. Firstly, over the last years, many different criteria have been used for the classification of Sp A, which comprise a group of relatively heterogenous diseases. Besides, classification criteria in Sp A do not mean necessarily a certain diagnosis and vice versa[125]. Secondly, these p atients, d ep end ing on the card inal manifestation, are follow ed up by a gastroenterologist or a rheumatologist that might overlook the articular or bowel manifestations of the disease, respectively. To that end, the effective communication between different professions and the interdisciplinary approach, through combined clinics for example, in imperative.

Treatment of this entities has progressed significantly over the last years. To the successful anti-TNF reagents, drugs targeting IL-23 and IL-17 as w ell as the JAKinhibitors have been added to the clinician's arsenal. However, treating patients with co-existing Sp A and IBD, should not only include these manifestations but also considerate other extra-articular and extra-intestinal manifestations like skin disease or uveitis. Comprehensive algorithms, designed by clinicians of many disciplines are urgently needed, in light of the numerous emerging therapeutic modalities.

World Journal of Gastroenterology2019年18期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2019年18期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Effect of prophylactic clip placement following endoscopic mucosal resection of large colorectal lesions on delayed polypectomy bleeding: A meta-analysis

- Recurrent renal cell carcinoma leading to a misdiagnosis of polycystic liver disease: A case report

- Nested case-control study on risk factors for opportunistic infections in patients with inflammatory bowel disease

- Ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir + dasabuvir +/- ribavirin in real world hepatitis C patients

- Role of abdominal ultrasound for the surveillance follow-up of pancreatic cystic neoplasms: a cost-effective safe alternative to the routine use of magnetic resonance imaging

- Characteristics of mucosa-associated gut microbiota during treatment in Crohn's disease