Omission of Subject “I” in Subtitling: A Corpus Review of Audiovisual Works

Chester CHENG

The University of Queensland

Abstract This paper explores the pattern of omission in English to Chinese subtitling of the subject “I”. In translation, omission is used as a technique to manage the temporal and spatial constraints that exist with audiovisual formats. To date, little research has been done into how or why the omission takes place. The research reported on in this article is the first to explore and analyze the reasons behind omission in detail. It does so by utilizing a parallel and bilingual corpus, built up from fansub translations of audiovisual works, amounting to 4,743 subtitles and 138 valid tokens. The tokens are examined and discussed, and then categorized according to semantic usage in order to uncover the patterns of the omissions in the translations. The analysis shows that collocates have significant influence on whether “I” is omitted in the Chinese translation. Omission of “I” takes place more frequently when: a) it is a common practice to translate idiomatic expressions without a subject in the target language, such as “I am sorry” and “I’m afraid”; and/or b) discourse markers and hedging words are used in the source language, such as “I mean”, “I think” and so on. The findings of this paper are a contribution to the existing studies on the phenomenon of omission in audiovisual translation. They are significant for giving solid evidence for audiovisual translators to use in their decision-making process, for how and whether the subject “I” could be and/or should be omitted. They also indicate that the further investigation of the phenomenon through alternative points of view, such as pragmatics, is desirable.

Keywords: omission, omission pattern, audiovisual translation, subtitling, discourse markers

1. Introduction

The prevalent modes in audiovisual translation (AVT) are subtitling, dubbing and voice-over. Subtitling involves the overlaying of text in an audiovisual work translated from one language to another, and dubbing and voice-over involve overlaying or substitution of speech. Díaz Cintas and Remael (2007) point out that subtitling, dubbing, and voice-over are constrained by the images and sounds of an audiovisual program that a director wants to convey, as well as by time and space. For example, subtitles should be aligned with the actions of the characters on screen. Also, the delivery of the translation should coincide with the speech delivery, and subtitles should be accommodating to the width of the screen. Interplay between a translation mode and these constraints creates “a multisemiotic blend of many different codes” (Gambier, 2009, p. 17). When it comes to subtitling, omission thus becomes an inevitable phenomenon (Díaz Cintas & Remael, 2007, p. 162) and it is perhaps the most-used translation strategy (Toury, 1995, p. 82) adopted by audiovisual translators. However, the patterns of omission in subtitling are still unknown, mainly because such research requires a wide range of analysis of subtitles of various kinds and in different languages (Hatim & Mason, 1997, p. 68). This article is an attempt to find out the pattern in omissions of the subject “I”, as it may be present in English to Chinese subtitling.

Under some translation industry standards, omission in translation is regarded as an error. In Australia for example, the AUSIT (Australian Institute of Interpreters and Translators)Code of Ethics and Code of Conductsays that a source message or text must be transferred “without omission or distortion” (Australian Institute of Interpreters and Translators, 2012, pp. 5, 8). ThisCoderequires translators to strictly follow the source texts without any alteration. TheTranslator’s Charteron the other hand, published by the International Federation of Translators (1994) is not as strict as AUSIT’sCode. It clearly mentions that the translation “shall be faithful and render exactly the idea and form of the original” (Section I General obligations of the translator, Article 4), but the faithfulness required is “not excluding an adaptation to make the form, the atmosphere and deeper meaning of the work felt in another language and country” (Ibid., Article 5). This means omission is not a suggested approach, but could be considered acceptable in order to match the way the source and target audiences feel about the original and translated work, respectively.

Scholars share different points of view with regard to omission in translation. Although omission may be seen as a flaw of a translation, Davies (2007) observes that it may be a motivated choice or an adequate solution when the source text is simply untranslatable or unacceptable, or non-equivalent to or unnecessary in the target language. Omission may sound like a drastic strategy, but in some contexts it does no harm to omit a word or expression in translation (Baker, 2011, p. 42).

Translation strategies such as deleting, condensing and adapting the source speech have become common among audiovisual translators (Pérez-González, 2009, p. 16). On the one hand, meanings embedded in different codes need to be conveyed; on the other hand, the time and space for a subtitle is limited, and this may lead to difficulties in the conveyance of meaning. Hence, as mentioned, omission becomes inevitable when subtitles are translated (Díaz Cintas & Remael, 2007, p. 162).

Omission is perhaps the most used legitimate translation strategy in subtitling (Toury, 1995, p. 82). Is this still the case, however, in subtitling from English into Chinese? Research shows that when translating from English into Chinese, the lengths of the target text is over forty percent shorter than that of the source text (The Economist, 2012). Considering that the source and target texts share the same images and sound in subtitling, and assuming that sufficient time and space has been given in the audiovisual work that contains the source text, omission in the Chinese translation may not be necessary. However, on investigation we can see that empirically, omission does exist in English into Chinese audiovisual translation, and find that it does so for practical reasons. This leaves us with questions about why and how omission takes place for English into Chinese AVT.

Little research has been done to find out why and how omission takes place in a detailed manner. Working on the functionality of the interjectionoh, Matamala (2007) analyzed a corpus of English sitcoms and their Catalan translation. The interjectionohcan be processed by translating it into interjections, non-interjections or simply by being omitted. This research shows that omission is the main strategy for translatingohin sitcoms. Through a quantitative corpus-based approach by analyzing the subtitles of American and British films and their Italian counterparts, Pavesi (2013) found that when translating demonstrative pronouns, namelythisandthat, translators tend to omit the pronouns in general, making omission the most common approach. Jing and White (2016) have similar findings when investigating the English-Chinese translation of the interjectionsheyandohin a corpus consisting of seven different versions of subtitles of one single animation work:The Croods. They found that interpersonal elements are prone to omission in subtitling. By utilizing corpora and focusing on the audiovisual translation of various parts of speech such as interjections and demonstrative pronouns, all these researchers conclude that omission is the most common method used in the translation process.

This research described here has used a different approach in examining the translation from the omission point of view, to answer why and how such omission takes place. Preliminary research was conducted into pronouns generally, including I, you, he/she and they. The results show that different pronouns, with regard to whether they are omitted or not, reveal different patterns. It is found that among 4,764 lines of subtitles in the corpus used, a high proportion (74.64%, or 103 out of 138 tokens) of “I” omissions are where they are used as discourse markers and hedging words in collocation with other words, such asI’m sorryandI mean. This is different to the pattern for omission of the pronoun “you”. Among the 137 instances of “you” being omitted, the proportion of discourse markers and hedging words drops to only 11%. A significant percentage of the omissions (over 40%) take place instead in interrogative sentences. There are only 13 tokens showing a “he” or “she” being omitted. Most of them, 76.92% or 10 out of 13, can be clearly understood by referring to the adjacent sentence(s). The subject “they” shows a similar pattern to the “he/she” example. Because the differences among the omission patterns are significant, this paper will only focus on the omission of the pronoun “I”.

2. Data collection

It is believed that a parallel corpus will “facilitate investigation of the relationship between a translation and its source text” (Olohan, 2002, p. 153). One of the benefits of drawing on a corpus-based methodology is the superior quality of linguistic evidence when compared to the analyst’s intuition (Sinclair, 1991, p. 42). The fast searching and parsing capability of computer systems make possible the processing and analyzing of huge amounts of data. Corpus-based translation studies can be adopted to investigate the use and patterns of word-forms (Munday, 2016, p. 291), and this fits the purpose of this research. In this study, the word “corpus” represents a bilingual, parallel corpus of English and Chinese subtitles. In this section, the selection of data to be used will be presented. This is followed by a preliminary analysis and sanity check of the data, and the section concludes with the establishment of the corpus.

This paper examines language in audiovisual works of selected dramas and extracts parts of dialogue that exhibit omission of “I” in translation. It keeps in mind under which conditions an audiovisual work is suitable for research purposes. Hatim and Mason (1997, p. 70) suggest that the audiovisual work that suits research should (a) be a widely-distributed, full-length feature work with high quality subtitles; (b) be work where interpersonal pragmatics are brought to the fore; and (c) contain many sequences of verbal interaction such as sparring. Dialogues collected will be categorized according to varying aspects for the analysis later on.

The corpus being used in this research is the fourth season ofSherlockproduced by the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC, 2017), which contains three episodes. This TV series is “a thrilling, funny, fast-paced contemporary reimaging” (BBC, 2017) of the classic Sherlock Holmes detective fiction written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and published from 1886 to 1927. In this new TV series, instead of being in the late 19thto early 20thcenturies, Holmes is active in 21stcentury London, with its modern technologies such as mobile phones and computers. On the one hand, he enjoys fame because of his observance, intelligence, and prowess; while on the other hand, he is characterized as a high-functioning sociopath who is proud and insolent because of his talents. Hence, the dialogues in this TV series are full of sparring, sarcasm, and taunts in a smart, humorous, and sometimes cynical way. Both the scripts and acting makeSherlocka drama that enjoys widespread success, and it is highly-rated on various film commentary websites, with measures such as 9.2/10 (IMDb, 2017), 83% (Rotten Tomatoes, 2017) and 8.2/10 (Douban Movies, 2017). The TV seriesSherlockis a good candidate for the purpose of research because it meets the criteria set by Hatim and Mason (1997).

The Chinese translation chosen in this article is done by “YYeTs” (人人影视,ren-ren-ying-shi), one of the four largest fansub groups in China, known for its reputable quality in audiovisual translation. Fansub (a short form of “fan subtitled”) is an emerging topic in Translation Studies. It was earlier defined by Díaz Cintas and Muñoz Sánchez (2006, p. 37) as “a fan-produced, translated, subtitled version of a Japanese anime programme”, but now also refers to such versions of other audiovisual works (Bogucki, 2016, p. 65). The translation quality of the fansub groups and the technology they use have dramatically improved over the years. For this reason, only the latest season ofSherlockwill be used. For research purposes, it is not uncommon to use fansub groups’ translations as a research sample, such as for word and character frequencies (Cai & Brysbaert, 2010), similarities and differences in translation (F. Wang, 2014), social activism (D. Wang & Zhang, 2015, 2017), and many other topics. Because of its high quality, YYeTs’s translation has been used by various legitimate video distributors online, including Sohu (搜狐,sou-hu), Youku (优酷,you-ku) and 163.com (网易,wang-yi) (D. Wang & Zhang, 2015). Zhang (2017), the translator and project manager ofSherlockfrom YYeTs, mentions that generally two versions of the translation will be released for most subtitling projects on which they work. The first version is released within a few hours to a day of the audiovisual work being released or available on the internet. A thoroughly proofread version, which contains the amendments of all errors, will then be released within a week. This open- and crowd-sourcing workflow has been proven to be successful for ensuring the quality. Their translation ofSherlockeven came to be used by the legitimate video distributor. Such recognition gives credence to the translation quality ofSherlockcarried out by YYeTs. This research utilizes the proofread version of the translation to build the corpus.

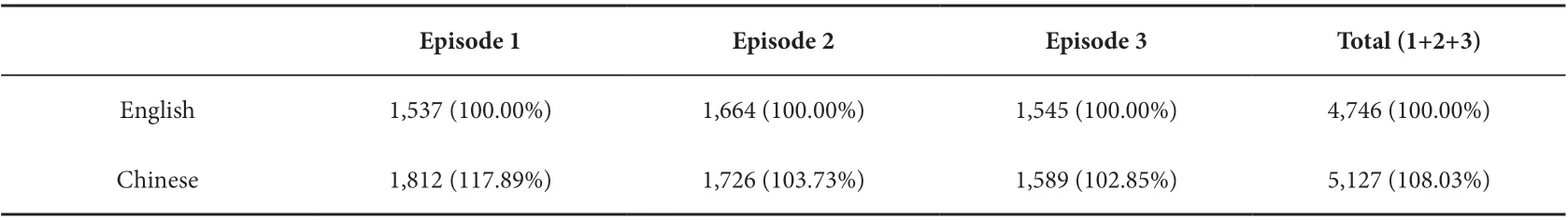

To build the corpus, both English and Chinese subtitles fromSherlockseason four on the YYeTs website were collected. At the time of writing, season four is the latest available season. All three episodes of season four are selected based on the translation quality having been recognized by the legitimate video distributors. Because the number of subtitles in the two languages does not match, they are manually paralleled. The process to match subtitles in both languages is determined by their start and end times. It is worthwhile mentioning that on average there are more Chinese subtitles than English ones, by an extra 8.03%, as seen in Table 1 below.

Table 1. Numbers and percentages of English and Chinese subtitles in Sherlock Season 4

The extra subtitles in Chinese are the copyright disclaimer, the credits for YYeTs staff, and the translation of intralingual language such as signs and mobile messages that were shown on the screen but not in the English subtitles. The extra Chinese subtitles have been removed from the corpus so that the numbers of both English and Chinese subtitles do match. After paralleling, a corpus is established consisting of three columns: the ID or serial number of the subtitle, the source text, and the target text. A snapshot of the corpus representing information fromSherlockseason 4 episode 1 looks like this:

1, “How’s your blog going?”,“你的博客写得怎么样了”

2, “Yeah, good, very good.”,“很好 真的”

3, “You haven’t written a word, have you?”,“你一个字都没写吧”

...

To identify the omissions of “I” in the corpus, a computer script as described below is used to filter out ST with an “I” and TT without awo(我, “I” in Chinese). Other forms ofwo, such asan(俺),wu(吾) and others, were also considered, but none of them appeared in this corpus. The result is used for data analysis.

The basic content of the script is:

grep “I ” corpus.txt | grep --invert-match “我”

In this script, the command “grep” is used to search “the occurrence of a string of characters that matches a specified pattern” (Proffitt, 2018). The first part of the script grep “I ” corpus.txt tries to filter out the subtitles that contain “I ”. Specifically, the letter “I” is followed by a space, so that other words that contain a capital “I” are excluded. The result is sent to the second part of the script grep --invertmatch “我” in which grep will filter out all subtitles that do not containwo(我), with the parameter --invert-match being implemented. Between the two grep commands, a “pipe” sign (|) is used to redirect the result of the first grep to the second.

The script will be used against other variations of “I ”, such as “I,”, “I;”, “I.”, “I?”, “I’”, and “我”, such as “俺” (an), “吾” (wu), “咱” (zan), “朕” (zhen), “侬” (nong), “臣” (chen). Below is an example of executing the script to search for subtitles that contain “I ” withoutwo(我):

grep “I “ corpus.txt |grep --invert-match “我”

12,”Well, I certainly hope you’ve learnt your lesson.”,”希望你吸取教训了”

40,”I am. Utterly.”,”是的 全戒了”

50,”Ice lolly, I suppose.”,”那就吃根冰棍吧”

…

After going through all the variants of English I and Chinesewo, subtitles that contain English “I” but without any kind of Chinesewoin the translation, are what will remain for data analysis.

3. Data analysis

The analysis of the data shows 858 instances of “I” in the corpus with 138 wo omissions. The omission rate is 16.08%, and this rate will be used as an indication for analysis. The 138 tokens are categorized into groups according to their grammatical structure and characteristics. Some of the categories hold significantly higher rates than the average rate. Categories with high rates will be discussed below, and the list of the tokens which are higher than average will be presented in the Discussion section.

3.1 I’m (so/very/terribly) sorry

“Sorry” stands out as a grouping in the omission of “I” in the subtitles. This grouping includes “I’m sorry”, “I’m so sorry” and “I’m very sorry”, as well as the question form “I’m sorry?” which will be discussed in the following section. There are 29 “I’m (so/very) sorry” instances, and 22 of them have the subject “I” omitted. This comes to 75.86%, which is a significantly higher rate than the average. In some cases, “I’m sorry” is used as an apologetic form to show one is sorry. Such an apologetic expression in English is often translated into Chinese with the idiomaticbaoqian(抱歉, to be sorry),buhaoyisi(不好意思, to feel embarrassed) orduibuqi(对不起, excuse me). These three most common ways of expressing one’s sorriness (Shi & Li, 2015), are all without an “I”. The translation of “I’m sorry” in this corpus is mapped closely to the expression. That is to say, at word level “I” is omitted but there’s no meaning loss at the idiom level or above. In example (1), the speaker expressed her feeling by an accumulative “I’m sorry. I’m so sorry.” These are translated as “Sorry. Very sorry.” without the “I”. To translate “I’m sorry” into Chinese without “I” is common practice.

(1) ST1Throughout the examples in this paper, ST, TT and BT stand for the source text, target text and back translation, respectively.: You just look after them till I get back. I’m sorry. I’m so sorry.

TT: 你照顾好他们 直到我回来 抱歉 非常抱歉

BT: You take good care of them till I come back. Sorry. Very sorry.

“I’m sorry” is also used for disagreeing with someone’s opinion in a polite way. In the example below, the speaker does not agree with the hearer that it is necessary to do something. In this scene, she speaks in a low tone as if she is praying her husband will not find her.

(2) ST: I’m sorry, my love.

I know you’ll try to find me but there is no point.

TT: 对不起 亲爱的

我知道你会去找我 但这没有任何意义

BT: Sorry, darling.

I know you’ll find me, but this doesn’t mean anything.

“I’m sorry” is also used for expressing one’s opinion or attitude. In example (3), the speaker tries to warn Dr. Watson not to move, or else the grenade will be set off.

(3) ST I’m sorry, Dr Watson, any movement will set off the grenade.

TT 抱歉 华生医生 一点动作都会引爆手雷

BT Sorry, Dr. Watson, a slight movement will set off the grenade.

The examples above show “I’m sorry” in different contexts. Their translations are typically the idiomaticbaoqianorduibuqi. The subject “I” is missing, but it causes no loss to the meaning of the ST.

There is a further point of interest apparent for investigating the phenomenology of omissions in the “I’m sorry” series. In the corpus, 18 instances of “I” out of 20 have been omitted in “I’m sorry”, 3 out of 5 were omitted in “I’m so sorry”, and none out of 2 in either “I’m very sorry” or “I’m terribly sorry” (see Table 2). It seems there is a tendency that the sorrier in the sentences one is, the less likely it is that “I” will be omitted. It could be the case that when the wordwoexists, the main point of the Chinese “I’m very/terribly sorry” sentences has been shifted from the behavior of showing one’s feeling to the subjective experience of the individual who wants to express his/her sorriness. The number of tokens in this research may not be large enough to support the finding. It may however be of interest to look into this topic further with a larger amount of data in the future.

Table 2. Omission rate of “I” in I’m (so/terribly) sorry.

3.2 I’m sorry?

Among the “I am sorry” category, the question form “I’m sorry?” stands out. All examples in this question have been translated without an “I” in the target language. Often related to “Pardon?”, “I beg your pardon?”, “Say again?” or its shortened form “Sorry?”, “I’m sorry?” asks the speaker to repeat, or to further explain what has just been said. In example (4), Sherlock congratulates a detective who, not knowing what Sherlock means, quickly asks Sherlock “I’m sorry?” in order to get a further explanation as to why he offers his congratulations. The translation clearly asks after the detective’s intention: “Congratulate what?”

(4) ST A: Congratulations, by the way.

B: I’m sorry?

A: Well, you’re about to solve a big one.

TT A: 顺便说一句 恭喜

B: 恭喜什么

A: 你就要破一桩大案了

BT A: By the way, congratulations.

B: Congratulate what?

A: You’re going to solve a big case.

Example (5) references a question Sherlock asks his client as to whether she owns an American car, or to be more specific, a left-hand drive car. Not knowing his intention, she asks “I’m sorry?” attempting to become sure of what Sherlock really means. The translation is literally translated as “What did you say?” which is one of the ways of expressing “Beg your pardon?” in the Chinese language. Instead of saying the subject has been omitted, which of course it actually has, the translation is in fact an adaptation that fits the context. The translation of “I’m sorry” has been changed and adapted to fill the gap of the conversation that may confuse the viewer.

(5) ST A: No, do you own an American car?

B: I’m sorry?

A: No, not American, left-hand drive, that’s what I mean.

TT A: 没有 你有美国车吗

B: 你说什么

A: 不 不是美国车 我的意思是左舵车

BT A: No, do you have an American car?

B: What did you say?

A: No, not an American car. I mean a left-hand drive car.

3.3 I’m afraid

All of the instances of “I’m afraid” involve an omission of the subject. The term “I’m afraid” is a polite way to tell people something might make them sad, disappointed, or angry (Rundell, 2017). A general practice for the translation of “I’m afraid” into Chinese iskongpa(恐怕), in which case a subject is not needed, as shown in example (6). This again shows the omission of “I” is caused at the idiom level, rather than the word level. In example (7), the translator decided to remove the whole idiom “I’m afraid” while keeping the rest of the sentence. The meaning has not been changed, but the tone in the TT is different from the ST.

(6) ST I’m afraid it’s far worse than that — your wife is a spy.

TT 恐怕事实糟得多 你太太是间谍

BT (I’m) afraid the fact is much worse. Your wife is a spy.

(7) ST Daddy has things to do, I’m afraid.

TT 爸爸还有事要做

BT Daddy has things to do.

In example (8), the speaker asks, “But nothing will ever be the same again, will it?” The polite and reserved response “I’m afraid it won’t.” has been translated into a very simple “Yah.” or “Yes.” It is important to mention that in the English and Chinese languages, the responses to a negative sentence are different. Using the sentences in this example, an English response will be “No, it won’t.” while in Chinese “Yes, it won’t.” By way of explanation, the latter will mean something like: “Yes, (you are right;) it won’t.” A reserved, or hedged, tone is the purpose of “I’m afraid”. In some cases, such as (9), the reserved tone is preserved in an apologetic way in the TT and translated as “Sorry”. Different from example (7) in which the translator decided to keep the meaning but sacrifice the tone, example (9) keeps both the meaning and the tone.

(8) ST A: But nothing will ever be the same again, will it?

B: I’m afraid it won’t.

TT A: 一切都会不同了 是吧

B: 是啊

BT A: Everything will be different. Isn’t it?

B: Yah.

(9) ST There will, I’m afraid,

be regular prompts to create an atmosphere of urgency.

TT 抱歉 会定时出现情况紧急的提示

BT Sorry. Prompts of emergent situations will appear regularly.

3.4 I mean

“I mean (to say)” is used for “adding a comment or explaining what you have just said” or “correcting a mistake in something you have just said” (Rundell, 2017). It “marks a speaker’s upcoming modification of the meaning of his/her own prior talk” (Schiffrin, 1987, p. 295). In the corpus, “I mean” is used in similar senses which often makes the subtitles too lengthy to be displayed on the screen. The spatial restriction of subtitling has entailed that over half (58.33%) of the “I mean” instances have been omitted in order to keep the conversation short. In example (10), after answering that “anyone who paid well” would be her boss, the secret agent justifies that further by explaining, “we were at the top” in the secret service, implying why she and her partners could limit job acceptances this way. Here, “I mean” is used as a marker, or a link, to say something in another way. The translation has missed out the link, and the logic of the two sentences becomes weak.

(10) ST A: Who employed you?

B: Anyone who paid well.

I mean, we were at the top of our game for years.

TT A: 你们的老板是谁

B: 谁付钱多就是谁

我们多年来是圈里最好的

BT A: Who’s your boss?

B: Anyone who paid well.

We were the best in the circle for years.

The same is not the case, however, in the following example. The coherence of the contents in the ST is strong and that ties the sentences together. In this example, “What would you give ‘to get her back’ … [and] ‘to save her’?” are similar clauses. “I mean” is more of an interruption and does not play a strong link between these two sentences, so the logic has not been compromised when “I mean” is omitted in the translation.

(11) ST What would you give to get her back?

I mean, if you could, if it was possible, what would you do to save her?

TT 如果她能回来你愿意付出什么代价

如果可以 如果这是可能的

你愿意付出什么代价救她

BT What would you pay to get her back?

If (you) could, if it was possible, what would you do to save her?

3.5 I think

“I think” is used to “reduce the force of a statement, or to politely suggest or refuse something” (Proffitt, 2018). It is used as an epistemic parenthesis, implying the speaker exhibits “lack of commitment” or “uncertainty”, though paradoxically it may also express certainty (Aijmer, 1997). In example (12), the speaker tries to soften her tone when telling the hearer she certainly knows what to do. Even with the softened tone of “I think”, the audience can still tell her firm attitude, from either her facial expression on the screen, or from the exclamation mark at the end of the ST. The straightforward expression in the TT where “I think” is omitted is equivalent to ST, because the softened language is offset by the video elements.

(12) ST I’m a nurse, darling — I think I know what to do!

TT 我是护士 亲爱的 我知道该做什么

BT I’m a nurse, darling — I know what to do.

The example of the uncertainty of “I think” here may be cross referenced to example (15), in which the “I think” implies that the speaker is not fully sure. In the TT, it is omitted. The uncertainty, however, is preserved and carried over successfully using the “maybe” in the translation. Further discussion of the instances of “I think” are made in the next section.

4. Discussion

The aforementioned cases come from the statistical data of the corpus. It is time now to look at the data overall. Which words that combine with “I” have a higher probability of causing omissions of “I”? Statistics shows that the rate of omission of “I” is highly dependent on the collocates that are associated with the “I”. This suggests that the omitting of pronouns should be discussed at the idiom level, rather than word level. Figure 1 shows that high numbers of omissions are concentrated on phrases such asI’m sorry, I mean, I think, I know, I’m afraid, andI’m sure. Other cases do happen, but only with low numbers however. Cases with low frequencies are not listed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Instances of “I” omitted.

Apart from the number of omissions, percentage rates are also good indicators. Throughout the corpus in this research, “I” has been omitted 138 times out of 858 tokens, with an average rate of 16.08%. Among the omission tokens, however, some show higher rates of “I” omissions. Some combinations tend to have higher chances for omissions than others, and an overall pattern may be seen. Figure 2 shows the tokens that have a higher rate of “I” being omitted than the average. Cases with low frequencies are not listed.

Figure 2. Percentages of “I” omitted.

We could not but wonder if there isn’t a general explanation covering the variety of words for omissions of “I”? It becomes clear that there is a high tendency of omission happening among some of them, i.e.I mean, I think, I suppose, I guess, I assume, andI bet; andI’m sorry... but, I’m afraidandI’m sure. These words grouped according to their semantic usage are all discourse markers and hedging words.

Carter, McCarthy, Mark, and O’Keeffe (2011) saw that discourse markers (DMs) are words or phrases used to “connect, organize and manage what we say or write” or to “express attitude”, such asso, right, okay, andwell. Hedging words (or hedges) are “devices used to build a relationship between the author and his/her readers” (Norberg, 2011) and they “indicate the author’s attitude towards a given proposition” (Norberg & Stachl-Peier, 2015). They are mitigating words used to make one’s language less certain or definite (Rundell, 2017), or to soften one’s oral or written language (Carter et al., 2011).

A thorough discussion of DMs and hedges would be out of the scope for this paper. Therefore, we will only focus on the DMs and hedges that relate to the tokens in this research, or to be specific, the subtitles that involve an omitted “I” that are mentioned above.

One of the functions of DMs is to show the speaker’s attitude. Examples in our corpus include “I’m sorry”, “I’m afraid”, and “I think”. The speaker who says “I’m sorry” may want to show his/her sorriness. An example can be seen in (1) where the speaker, a former secret agent, couldn’t be sorry enough because she had to leave her husband and little daughter for their safety. As a DM, “I’m sorry” is used to connect, organize, and manage the conversation. It generally appears in the pattern “I’m sorry, but...” followed by the expression that may make the listener disappointed or angry. Taking (13) as an example, the speaker says, “I’m sorry, but...” in an attempt to assert his consequential statement: “…but I’ve never been to anywhere around your home”. The question form “I’m sorry?” as discussed in an earlier section does not function as a DM; it simply acts as a question to confirm the speaker’s intention.

(13) ST: I’m sorry, Mr Holmes, but

I don’t think I’ve ever been anywhere near your flat.

TT: 不好意思 福尔摩斯先生

但我应该没去过你家附近

BT: I’m embarrassed, Mr. Holmes

but I’ve never been to anywhere around your home.

Apart from showing one’s attitude, “I think” is also used for sounding less direct. Taking (14) below as an example, where with an “I think” in the ST, the tone becomes softened; while in the BT “you have to pull over” sounds like a rigid command that John has to follow. The softness disappeared in the TT because of the missing “I think”, and similar to (12), it may be an equivalent to the firm language and attitude being shown on the screen.

(14) ST John, John... I think you have to pull over!

TT 约翰 约翰 你得靠边停车

BT John, John, you have to pull over

A DM also functions as monitoring language: to say something in another way (e.g.I mean), or to share knowledge (e.g.you know). Example (15) happens to have these two DMs. Speaker A would like to share his idea and initiate the conversation with a “you know”, followed by an “I think” to soften his tone as well as to show that he is not one hundred percent sure of his idea. In the TT, the whole sentence is re-written according to the context with both DMs being omitted. The translator may have his/her justification for the omission that we wouldn’t know. In this case, the softened tone and uncertainty have been kept with the use of a “maybe” in the translation.

(15) ST A: You know, I think that really might be it.

B: No, don’t get it.

TT A: , 可能他真的需要

B: 不 不明白

BT A: , Maybe he really needs (it).

B: No, don’t get it.

To summarize, DMs and hedges are used for facilitating a conversation in various ways. To translate them into Chinese, it often involves the omitting of the whole of the DMs or hedges, rather than omitting the subject alone. As Taylor (2009, pp. 218, 226) points out, although hedges (along with tag questions and vague language) appear less in film scripts than in our daily lives, their dynamic force “should not be underestimated in the phrasal analysis of subtitles”.

5. Conclusion

This article reports on research into patterns that may exist in omissions of the subject “I”, in English to Chinese subtitling. The data reveals that a large proportion of the omission takes place at the idiom level rather than at the word level. There is a strong tendency for omission of the subject with some collocates of “I”, and less often than with other cases in the Chinese translation. It may not always be a translator’s intention to omit the subject. The subject may have disappeared simply because it is common practice to translate some idiomatic expressions into Chinese without using the pronoun “I” (wo). Examples might be the translation of “I’m sorry” or “I’m afraid” intobaoqian/duibuqiandkongpa, respectively. However, the omission here does not necessarily imply mistranslation. Most of the tokens in the data containing a missing “I” are closely equivalent in meaning when comparing between the source and target languages. Discrepancies in meanings are rarely observed. A large proportion of the omissions take place when the collocates function as discourse markers or hedging words. These are used for organizing and monitoring, for showing attitudes and responses, and for sounding less direct. Based on the findings, it is safe to say that the omission pattern of “I” is revealed when observing collocates with other words, especially when these are used as discourse markers and hedges. An expanded investigation of the omission phenomenon in discourse markers and hedges including but not limited to “I” could be of future interest.

The findings of this research complement the existing research related to the omission phenomenon in English to Chinese audiovisual translation. The findings are useful for audiovisual translators to support decisions on whether or when to condense their translation on screen when faced with temporal and/or spatial constraints, while at the same time retaining the meanings in the target texts as much as possible. The omission patterns of “I” discussed may also provide them with useful insights for the translation of discourse markers and hedges. They can inform their practice learning from the patterns provided in this paper, to employ omission as a technique in a way that does not compromise the tone, meaning, and/or the pragmatic usage of the source texts.

- 翻译界的其它文章

- A Sociological Investigation of Digitally Born Non-Professional Subtitling in China

- The Development and Practice of Audio Description in Hong Kong SAR, China

- A Shift in Audience Preference From Subtitling to Dubbing?—A Case of Cinema in Hong Kong SAR, China

- The Subtitling of Swearing in Criminal (2016) From English Into Chinese: A Multimodal Perspective

- Identity Construction of AVT Professionals in the Age of Non-Professionalism: A Self-Reflective Case Study of CCTV-4 Program Subtitling

- Constraints and Challenges in Subtitling Chinese Films Into English