Congenital bronchobiliary fistula:A case report and review of the literature

Tian-Yu Li,Zhi-Bo Zhang

Abstract

Key words: Congenital bronchobiliary fistula;Neonate;Computed tomography;Bronchoscopy;Fistulography;Case report

INTRODUCTION

Congenital bronchobiliary fistula (CBBF) is a rare developmental abnormality with an abnormal fistula between the respiratory system (trachea or bronchus) and biliary tract.Patients with this anomaly may develop symptoms at any time from neonate age to adulthood,but most of them present with signs of apnea,bilious saliva,and choking,within just a few days after birth.Generally,the earlier the symptoms appear,the more serious the condition is.CBBF is often accompanied by biliary tract developmental anomalies,such as biliary atresia.Surgical resection of the fistula is the ultimate choice of treatment.Presently,this anomaly is believed to be caused by abnormal development of the foregut[1-3].In this paper,we describe a patient with CBBF who showed the symptom of apnea at 3 d after birth,summarize the clinical data,and review the related papers on CBBF.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

Intermittent cyanosis for 3 d.

History of present illness

A full-term female baby of 5 d was referred to our hospital because of intermittent cyanosis.She secreted a large amount of yellowish and green saliva and started choking since 3 d of age.Respiratory distress became increasingly severe after admission,so tracheal intubation and a ventilator were applied thereafter.After intubation,yellowish green fluid kept flowing out of the tracheal tube.Gastroesophageal reflux complicated by a tracheoesophageal fistula was considered first,but nasogastric depression produced colorless fluid,which was not in accordance with the aforementioned findings.

Physical examination upon admission

Jaundice.

Laboratory examinations

Total bilirubin 172.4 μmol/L.

Imaging examinations

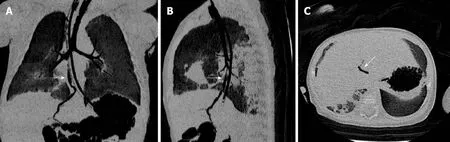

We performed 3-dimensional (3D) computed tomography (CT) of the baby’s chest.Her trachea and esophagus were reconstructed,and an abnormal fistula originated from the right bronchus;the fistula formed down along the esophagus and passed through the diaphragm into the intrahepatic biliary tract at the site of the esophageal hiatus.Gas was noticed in the intrahepatic biliary tract and common hepatic duct.Furthermore,pneumonia was evident in both lungs,especially in the lower lobes(Figure 1A-C).CBBF was diagnosed accordingly.

During the ultrasonographic examination,we discovered an abnormal fistula similar to that detected by CT.Ultrasonography also detected an accumulation of gas in both intrahepatic bile ducts,the common hepatic duct,and gallbladder,and gas bubbles in the biliary system moved with the patient’s breathing.No signs of biliary atresia were noticed during the ultrasonographic examination.

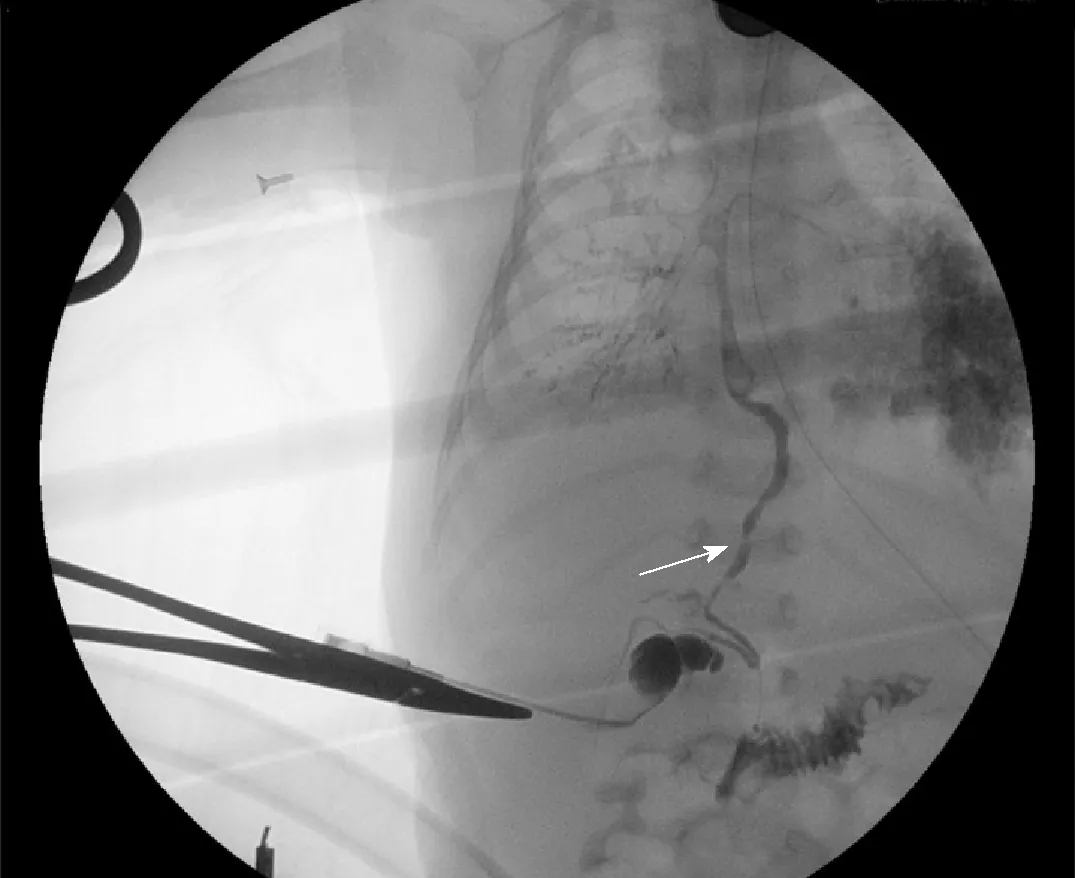

Flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy showed an abnormal opening at the right main bronchus;contrast was injectedviathe opening,and beside radiography was performed,which showed the outlines of the fistula,biliary tract,gallbladder,and duodenum (Figure 2).

Figure 1 Computed tomography images.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Congenital bronchobiliary fistula.

TREATMENT

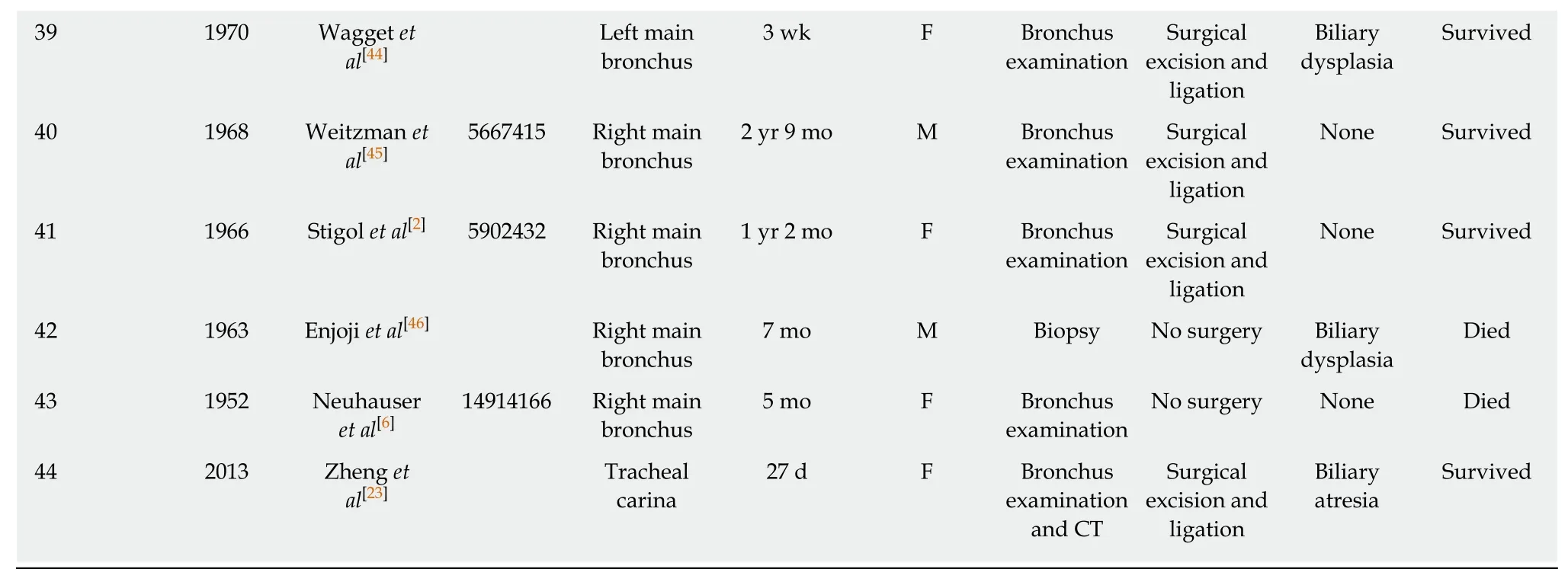

We initially performed laparoscopic biliary tract exploration and cholangiography to rule out biliary tract malformations.We found that the gallbladder was filled with green viscous bile,and the distal bile duct was patent.The abnormal fistula that bridged the intrahepatic bile duct and right bronchus was visible (Figure 3).Then,we performed posterolateral right thoracotomy at the sixth intercostal space.Green bile salt was deposited extensively beneath the visceral pleura.We dissected the mediastinal pleura and detected the fistula alongside the esophagus.The fistula formed down from the right bronchus to the right side of the hiatus,and it was about 4 mm in diameter and as soft as the esophagus.We punctured the lumen but produced nothing;then 10 mL of methylene blue was injected into the gallbladder,and the blue material was noticed subsequently at the puncture site and intratracheal tube (Figure 4).The fistula was confirmed accordingly.We separated the fistula and dissected it from the bronchus to the hiatus;both ends were securely ligated and sutured.Lastly,a thoracic drainage tube was placed.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

On the day 3 postoperatively,the child was successfully weaned from the ventilator.She was in good condition with satisfactory pulmonary expansion and feeding tolerance.We attempted to remove the thoracic drainage tube but failed;subsequently,the baby developed pneumothorax and subcutaneous emphysema,which were considered due to improper operation,so the tube was reinserted.On day 7 postoperatively,the child developed cholestasis with a total bilirubin level of 71.6 μmol/L and conjugated bilirubin level of 58.1 μmol/L.Ultrasonography showed mild obstruction of the extrahepatic bile duct and slight dilation of the common bile duct.Two possibilities were considered:first,the extrahepatic bile duct was not patent enough to drain all the bile produced by the liver sufficiently;and second,inflammation and edema caused by the operation resulted in partial obstruction of the bile duct.Methylprednisolone was administered,and her bilirubin level decreased to normal range 3 d later.On day 10 postoperatively,growing chylous fluid was noticed in the drainage,so the oral feeding was withdrawn accordingly.Ten days later,the drainage gradually decreased,oral feeding was resumed without adverse reactions,and the drainage tube was removed.The baby recovered well and was discharged.She has been followed for 4 mo without any signs of discomfort.

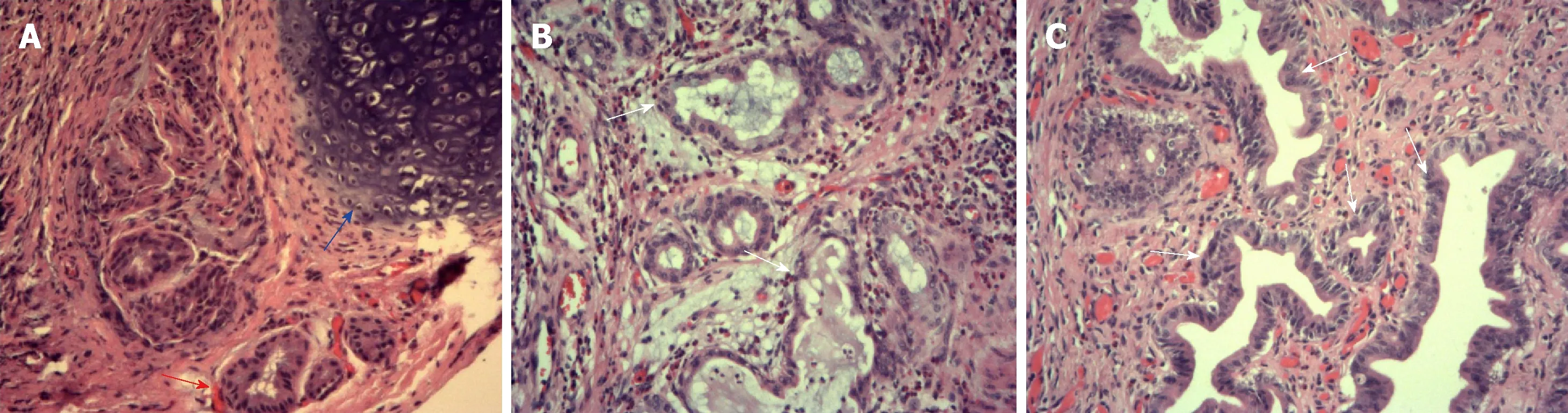

A microscopic examination was performed separately for three parts of the removed fistula.Scattered mature and naive hyaline cartilage surrounded by clustered bronchial glands could be seen at the part near to the bronchus.Hyperplasia,angulation,aggregation,and columniation of the biliary glandular epithelial cells were found at the biliary end.The middle part was characterized by scattered,clustered glands,columniation of the glandular epithelia,squamous metaplasia,and cartilaginous tissue around the bronchial glands (Figure 5A-C).

Figure 2 Contrast study via a fiberoptic bronchoscope.

DISCUSSION

CBBF can manifest as a series of symptoms caused by an abnormal connection between the hepatic duct and trachea or bronchus.The onset time and severity of symptoms are related to the diameter of the fistula;therefore,the symptoms can appear at any age from newborn to adulthood.However,most of them occur in newborns and infants.The main clinical features of CBBF are recurrent coughing,bilious sputum,or bile-stained sputum in tracheal intubation.Patients generally develop progressive dyspnea,cyanosis,severe pneumonia,respiratory distress syndrome,and even apnea;shortly after birth,mechanical ventilation is often needed.Bile-stained expectoration is the most typical sign among the aforementioned symptoms.It has been often misdiagnosed as an esophagotracheal fistula,gastroesophageal reflux,aspiration pneumonia,or high intestinal obstruction[4,5].

The first findings on CBBF were reported in 1952 by Neuhauseret al[6].Altogether,there were 43 additional cases reported in English and 1 in Chinese thereafter (Table 1),and CBBF was more common in women than in men.An abnormal fistula can be opened at different positions around the carina:right main bronchus (20/44,45.4%),carina (19/44,43.2%),and left main bronchus (5/44,11.4%).Fistulas generally passed through the esophageal hiatus and entered into the abdominal cavity;all fistulas communicated with the intrahepatic bile duct (left hepatic duct),except one fistula that opened at the common bile duct[7].

The pathogenesis of this disease is not clear yet.Abnormal development of the bronchial bud,which fuses with the bile duct,was regarded as the cause of the anomaly.Other reports postulated that CBBF was the result of digestive tract duplication and the upper respiratory tract[1,6,8-10].

As in most reports,the proximal part of the fistula had the characteristics of the respiratory tract,consisting of cartilage,pulmonary epithelia,glands,and smooth muscle,whereas the distal part was similar to the gastrointestinal tract.In our case,by examining the proximal,middle,and distal parts of the fistula,we found scattered mature hyaline cartilage,relatively naive cartilage,and clusters of bronchial glands at the bronchus end;whereas,glandular epithelia of the bile duct and interstitial cholestasis were found at the distal part of the fistula.In the middle part,the lumen was partly covered by pseudo-ciliated columnar epithelia.Cartilage rings lay beneath the mucosa.Co-existing single-layer columnar epithelium could also be seen in the same field.These histological findings could further verify the pathogenesis of CBBF.

CBBF was often complicated by biliary atresia,diaphragmatic hernia,esophagus atresia,and tracheoesophageal fistula,and the incidence of biliary malformation in this group was about 30%[11-15].As long as this possibility was considered,the diagnosis of CBBF was not difficult.Magnetic resonance imaging,3D-CT reconstruction,bronchoscopy,and ultrasonography can provide valuable clues.Bronchoscopy was the most common method for making a diagnosis,as it can b used to find the abnormal opening of the fistula and the overflowing bile via th opening[13,14,16-19].3D-CT reconstruction can accurately detect the existence of the fistula which is of great significance for diagnosing CBBF.In the present case,the CT scan provided us with the first evidence of the abnormal fistula.Then fiberopti bronchoscopy was performed,and a contrast dye was injected into the fistula once th opening was confirmed.Next,a radiographic examination was conducted;thus,th opening,shape,and connection of the fistula were all confirmed.The result of ou treatment was excellent,and to our knowledge,this method has not been reported previously.ee,ceer

Figure 3 lntraoperative cholangiogram showing the connection between the biliary tract and right bronchus and patent distal bile duct;the white arrow indicates the biliary tract.

Surgical resection was the ultimate treatment of choice,but a specific method must be considered according to different anatomical structures[20-22].According to previous reports,different kinds of operative methods have been used,such as hepatic lobectomy,anastomosis of the gallbladder or intestine with abnormal fistulas,and fistula resection.We think that it is necessary to consider whether there is a biliary tract anomaly when preparing an operative plan.If a biliary anomaly exists,biliary reconstruction must be considered[4,14].We performed laparoscopic cholangiography first during the operation to exclude biliary atresia,and achieved a satisfactory result.We performed thoracotomy subsequently,and explored and identified the fistula in the mediastinum;the fistula formed down the right side of the esophagus.We punctured the lumen for assurance because there are many important structures nearby,and then we injected methylene blue into the gallbladder;the dye was seen flowing out of the puncture site,thus the fistula was confirmed.Because the extrahepatic biliary tract was normal,reconstruction was unnecessarily considered.Instead,we just separated the fistula and ligated and sutured it at the upper end and at the hiatus,and then the fistula was removed.

The overall mortality of CBBF was 15.91% (7/44) according to the literature,and three patients died of respiratory complications without surgery.Our patient experienced chylothorax shortly after thoracotomy,which may be due to injury of the thoracic duct when we dissected the fistula at the hiatus.Fortunately,she recovered after short-term conservative management.Cholestasis was another main complication encountered postoperatively,and ultrasonography showed slight dilatation of the bile duct.We evaluated her conditions and prescribed methylprednisolone.Cholestasis resolved after three doses;therefore,we deduced that the jaundice may have been due to temporary inflammation of the biliary tract.

CONCLUSION

Most surgeons may not encounter CBBF in their professional career considering its rarity.Its clinical symptoms are typical and special such as bile-stained expectoration.As long as surgeons have some insight into this kind of condition,its diagnosis and treatment are not difficult,and the prognosis would be excellent for most patients.

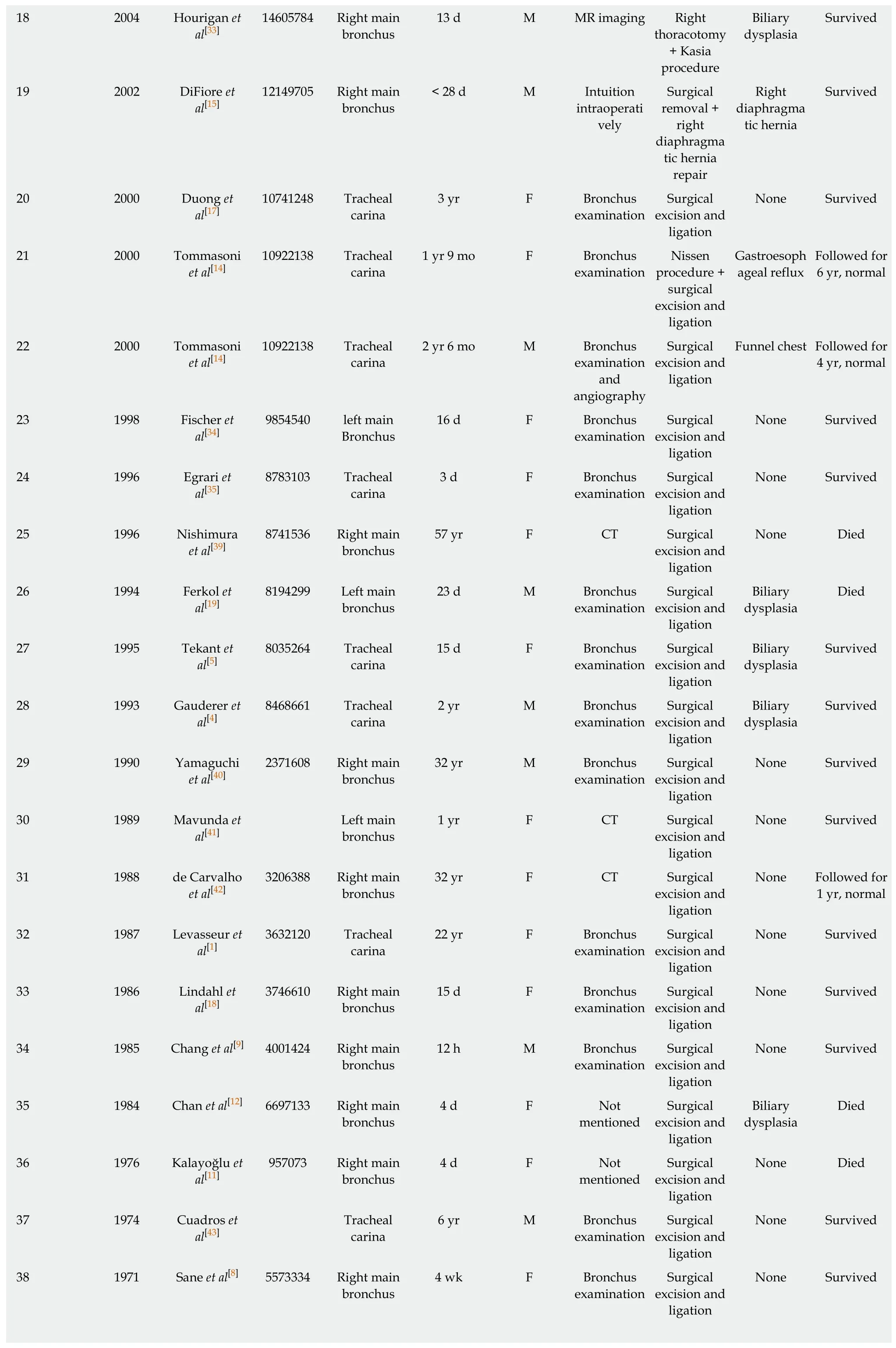

Table 1 All cases of congenital bronchobiliary fistula reported to date

18 2004 Hourigan et al[33]14605784 Right main bronchus 13 d M MR imaging Right thoracotomy+ Kasia procedure Biliary dysplasia Survived 19 2002 DiFiore et al[15]12149705 Right main bronchus< 28 d M Intuition intraoperati vely Surgical removal +right diaphragma tic hernia repair Right diaphragma tic hernia Survived 20 2000 Duong et al[17]10741248 Tracheal carina 3 yr F Bronchus examination Surgical excision and ligation None Survived 21 2000 Tommasoni et al[14]10922138 Tracheal carina 1 yr 9 mo F Bronchus examination Nissen procedure +surgical excision and ligation Gastroesoph ageal reflux Followed for 6 yr,normal 22 2000 Tommasoni et al[14]10922138 Tracheal carina 2 yr 6 mo M Bronchus examination and angiography Surgical excision and ligation Funnel chest Followed for 4 yr,normal 23 1998 Fischer et al[34]9854540 left main Bronchus 16 d F Bronchus examination Surgical excision and ligation None Survived 24 1996 Egrari et al[35]8783103 Tracheal carina 3 d F Bronchus examination Surgical excision and ligation None Survived 25 1996 Nishimura et al[39]8741536 Right main bronchus 57 yr F CT Surgical excision and ligation None Died 26 1994 Ferkol et al[19]8194299 Left main bronchus 23 d M Bronchus examination Surgical excision and ligation Biliary dysplasia Died 27 1995 Tekant et al[5]8035264 Tracheal carina 15 d F Bronchus examination Surgical excision and ligation Biliary dysplasia Survived 28 1993 Gauderer et al[4]8468661 Tracheal carina 2 yr M Bronchus examination Surgical excision and ligation Biliary dysplasia Survived 29 1990 Yamaguchi et al[40]2371608 Right main bronchus 32 yr M Bronchus examination Surgical excision and ligation None Survived 30 1989 Mavunda et al[41]Left main bronchus 1 yr F CT Surgical excision and ligation None Survived 31 1988 de Carvalho et al[42]3206388 Right main bronchus 32 yr F CT Surgical excision and ligation None Followed for 1 yr,normal 32 1987 Levasseur et al[1]3632120 Tracheal carina 22 yr F Bronchus examination Surgical excision and ligation None Survived 33 1986 Lindahl et al[18]3746610 Right main bronchus 15 d F Bronchus examination Surgical excision and ligation None Survived 34 1985 Chang et al[9] 4001424 Right main bronchus 12 h M Bronchus examination Surgical excision and ligation None Survived 35 1984 Chan et al[12] 6697133 Right main bronchus 4 d F Not mentioned Surgical excision and ligation Biliary dysplasia Died 36 1976 Kalayoğlu et al[11]957073 Right main bronchus 4 d F Not mentioned Surgical excision and ligation None Died 37 1974 Cuadros et al[43]Tracheal carina 6 yr M Bronchus examination Surgical excision and ligation None Survived 38 1971 Sane et al[8] 5573334 Right main bronchus 4 wk F Bronchus examination Surgical excision and ligation None Survived

CBBF:Congenital bronchobiliary fistula;CT:Computed tomography;MR:Magnetic resonance;F:Female;M:Male.

Figure 4 Methylene blue was injected into the gallbladder,and it flowed out from the puncture site;the white arrow indicates the puncture site.

Figure 5 A microscopic examination performed separately for three parts of the removed fistula.

World Journal of Clinical Cases2019年7期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2019年7期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Ultrasound imaging of abdominal sarcoidosis:State of the art

- Porphyromonas gingivalis and digestive system cancers

- Clinical evaluation of endoscopic resection for treatment of large gastric stromal tumors

- Value of superb micro-vascular imaging in predicting ischemic stroke in patients with carotid atherosclerotic plaques

- Open anterior glenohumeral dislocation with associated supraspinatus avulsion:A case report

- Vein of Galen aneurismal malformations - clinical characteristics,treatment and presentation:Three cases report